|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:2

|

EDITORIAL

Autonomous vehicles and mental health

David Rojas-Rueda

Barcelona Institute of Global Health (ISGlobal), Barcelona, Spain

Barcelona Institute of Global Health (ISGlobal), Barcelona, Spain

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are about to initiate a mobility revolution that will shape the urban environment and modify the mental health of urban populations in the coming years. A fully autonomous vehicle is a vehicle that has a full-time automated driving system that undertakes all aspects of driving that would otherwise be undertaken by a human, under all roadway and environmental conditions. By 2020, we expect fully autonomous vehicles to be on the market, and by 2035 more than 30 million AVs will be on the streets. Currently, car makers are testing different versions of AVs that deliver various degrees of autonomy.

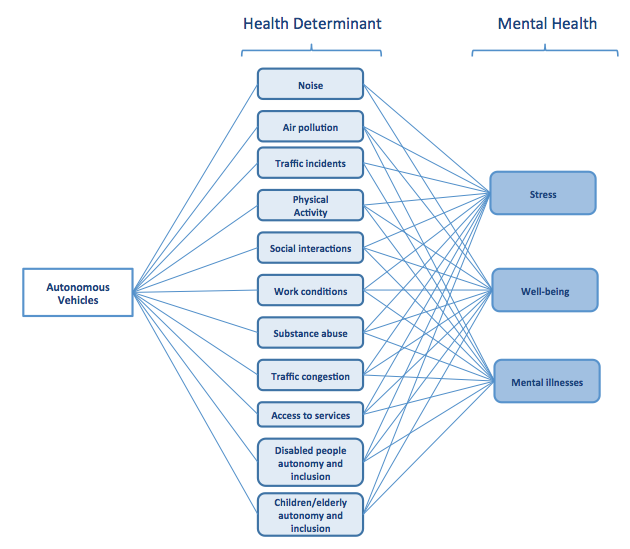

Vehicles that can drive themselves without human input will affect important health determinants associated with urban environments including public spaces, traffic injuries, social interactions, physical activity, air pollution, traffic noise, access to health services or substance abuse services. Many of these health determinants are associated with mental health (Figure 1).

Vehicles that can drive themselves without human input will affect important health determinants associated with urban environments including public spaces, traffic injuries, social interactions, physical activity, air pollution, traffic noise, access to health services or substance abuse services. Many of these health determinants are associated with mental health (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Autonomous vehicles and mental health framework

Impact on road safety and its consequences

Traffic injuries and fatalities are the most commonly discussed AV-related health determinant. We expect AVs will be able to avoid all traffic crashes associated with human errors (currently an estimated 90% of causes of all traffic crashes in Europe). AVs will modify our road safety perception, reducing the risk not just of crashes but conflict with other drivers, cyclists, pedestrians and others, mostly eliminating the stress of driving a car that can trigger mental distress and exacerbate mental health problems. Instead, the AV scenario will open up a new experience in mobility, with the possibility to relax and enjoy a safer, less stressed transit experience, whether riding in an AV or as a pedestrian or cyclist, encouraging more active transport.

Transformation of the commuting experience - but in a good or bad way?

Beyond elimination of the concentration, stress, and risk of injury currently associated with driving, AVs could transform the commuting experience by freeing up time in transit. Recently some future AV scenarios have offered a vision of how we could use this extra travel time. There could be substantial mental health benefits if driving time were substituted with relaxing and enjoying recreational activities in transit. However, these new ideas are also opening the door to using the commuting time for work activities. Could this mean that our commuting time becomes an extension of our work time? If so, there are two different ways this might evolve. The first way (and maybe the less probable) could offer people a shift in work time location from workplaces to AVs, starting and ending work while in transit. This incorporation of commuting time into the workday would eliminate the extra hours of commuting, freeing up more time for personal activities, including time for physical activity, and social time to spend with friends and family. Perhaps more likely, a second way will be an expectation that in-transit work forms an addition to our current work hours, the overall effect being exposure to increased work hours, which may be associated with work-related stress and potential health consequences including depression and anxiety. Either way, there is a risk that spending time working in an AV may just substitute driving stress with work-related stress.

Impact on accessibility and autonomy

AVs can help provide better access to more places and services, such as social and leisure activities, and health services, including improved access to health services for people with mental disorders. AVs will also open new opportunities to particular population groups such as disabled people, children or older people, who will particularly benefit from the increased autonomy AVs will offer. Autonomy has also been related to reduced stress, more motivation, and better mental health outcomes.

Impact on social interaction

AVs could facilitate increased access to venues for social interactions and social support that help promote good mental health. But private AVs could also increase isolation during travel periods. There is some evidence suggesting that increasing car use and time expended in cars are associated with less social interaction and cohesion between neighbors. Increasing the number of individual and private AVs (similar to current car use) and travel periods might maintain poor social interaction. But if the AVs are managed as shared vehicles this could produce the opposite effect, stimulating social interaction between travelers and improving social networks and support.

Impact on alcohol and substance abuse

Substance abuse is associated with depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, amongst other mental health problems. Traffic campaigns have been effective interventions to reduce substance abuse in drivers. If we no longer need to drive, then perhaps people will be less interested in controlling their consumption of alcohol or other drugs, which may result in increased alcohol and substance abuse. Regulations could be implemented in the future to reduce alcohol and substance abuse when riding in an AV.

Environmental impact

Environmental risk factors could also be affected when AVs reach our cities. Air quality and traffic noise, both correlated with stress, annoyance, and neurodevelopment problems, could be reduced if the AVs are designed as electric vehicles. Imagine a complete change of the vehicles fleet: with only electric AVs we would no longer have traffic noise, and there would be a vast improvement of air quality in our cities.

Placemaking opportunities

Finally, AVs offer an excellent opportunity to reshape our cities. If we bet on an AV model based on shared vehicles (as opposed to private/ individual AVs), we will be able to reduce the public spaces dedicated to cars. Imagine fewer cars on the streets and less car parking space: cities will have the opportunity to build more parks, plazas and public spaces dedicated to people, where we can enjoy our families and friends, interact with our neighbors, improve social cohesion, and create better communities. Furthermore, the cities will also have the possibility to increase physical activity, and access to nature creating new parks and green spaces that will help deliver an improvement of population physical and mental health.

We are facing many challenges with AVs, and mental health practitioners and urban planners need to understand the future implications of AVs in mental health, and support AV models (electric AVs and shared AVs) that will help reduce the risk of mental disorders and deliver mental health benefits for everyone. We are at the right moment to work to ensure that AVs achieve a better future for urban mental health.

Traffic injuries and fatalities are the most commonly discussed AV-related health determinant. We expect AVs will be able to avoid all traffic crashes associated with human errors (currently an estimated 90% of causes of all traffic crashes in Europe). AVs will modify our road safety perception, reducing the risk not just of crashes but conflict with other drivers, cyclists, pedestrians and others, mostly eliminating the stress of driving a car that can trigger mental distress and exacerbate mental health problems. Instead, the AV scenario will open up a new experience in mobility, with the possibility to relax and enjoy a safer, less stressed transit experience, whether riding in an AV or as a pedestrian or cyclist, encouraging more active transport.

Transformation of the commuting experience - but in a good or bad way?

Beyond elimination of the concentration, stress, and risk of injury currently associated with driving, AVs could transform the commuting experience by freeing up time in transit. Recently some future AV scenarios have offered a vision of how we could use this extra travel time. There could be substantial mental health benefits if driving time were substituted with relaxing and enjoying recreational activities in transit. However, these new ideas are also opening the door to using the commuting time for work activities. Could this mean that our commuting time becomes an extension of our work time? If so, there are two different ways this might evolve. The first way (and maybe the less probable) could offer people a shift in work time location from workplaces to AVs, starting and ending work while in transit. This incorporation of commuting time into the workday would eliminate the extra hours of commuting, freeing up more time for personal activities, including time for physical activity, and social time to spend with friends and family. Perhaps more likely, a second way will be an expectation that in-transit work forms an addition to our current work hours, the overall effect being exposure to increased work hours, which may be associated with work-related stress and potential health consequences including depression and anxiety. Either way, there is a risk that spending time working in an AV may just substitute driving stress with work-related stress.

Impact on accessibility and autonomy

AVs can help provide better access to more places and services, such as social and leisure activities, and health services, including improved access to health services for people with mental disorders. AVs will also open new opportunities to particular population groups such as disabled people, children or older people, who will particularly benefit from the increased autonomy AVs will offer. Autonomy has also been related to reduced stress, more motivation, and better mental health outcomes.

Impact on social interaction

AVs could facilitate increased access to venues for social interactions and social support that help promote good mental health. But private AVs could also increase isolation during travel periods. There is some evidence suggesting that increasing car use and time expended in cars are associated with less social interaction and cohesion between neighbors. Increasing the number of individual and private AVs (similar to current car use) and travel periods might maintain poor social interaction. But if the AVs are managed as shared vehicles this could produce the opposite effect, stimulating social interaction between travelers and improving social networks and support.

Impact on alcohol and substance abuse

Substance abuse is associated with depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, amongst other mental health problems. Traffic campaigns have been effective interventions to reduce substance abuse in drivers. If we no longer need to drive, then perhaps people will be less interested in controlling their consumption of alcohol or other drugs, which may result in increased alcohol and substance abuse. Regulations could be implemented in the future to reduce alcohol and substance abuse when riding in an AV.

Environmental impact

Environmental risk factors could also be affected when AVs reach our cities. Air quality and traffic noise, both correlated with stress, annoyance, and neurodevelopment problems, could be reduced if the AVs are designed as electric vehicles. Imagine a complete change of the vehicles fleet: with only electric AVs we would no longer have traffic noise, and there would be a vast improvement of air quality in our cities.

Placemaking opportunities

Finally, AVs offer an excellent opportunity to reshape our cities. If we bet on an AV model based on shared vehicles (as opposed to private/ individual AVs), we will be able to reduce the public spaces dedicated to cars. Imagine fewer cars on the streets and less car parking space: cities will have the opportunity to build more parks, plazas and public spaces dedicated to people, where we can enjoy our families and friends, interact with our neighbors, improve social cohesion, and create better communities. Furthermore, the cities will also have the possibility to increase physical activity, and access to nature creating new parks and green spaces that will help deliver an improvement of population physical and mental health.

We are facing many challenges with AVs, and mental health practitioners and urban planners need to understand the future implications of AVs in mental health, and support AV models (electric AVs and shared AVs) that will help reduce the risk of mental disorders and deliver mental health benefits for everyone. We are at the right moment to work to ensure that AVs achieve a better future for urban mental health.

About the Author

|

David Rojas-Rueda is an epidemiologist specializing in health impact assessment, risk assessment and burden of disease approaches. He completed his medical degree at the National University of Mexico and his general surgical residency at the University of Guadalajara, Mexico. From there, he completed a Masters degree in Public Health at the University Pompeu Fabra, followed by a doctoral degree in Epidemiology at the Center for Research in Environmental Epidemiology in Barcelona, Spain. He has worked on issues such as air pollution, physical activity, traffic accidents, diet, cardiovascular risk, lead poisoning, multiple occupational exposures, urban planning and public health. He is currently working on European projects on urban and transport planning and health (PASTA & TAPAS II) and exposome (Helix & Exposomics). David is involved in multiple health impact assessments on urban planning, transport planning and green spaces interventions in collaboration with local and national authorities and international organizations like the World Health Organization in several cities from the European Union, Morocco, Mozambique, Ghana, Bolivia, and Mexico.

Contact or follow him on Twitter at @drrbcn |

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS