|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;2:4

|

Neighbourhood Amenities and Depressive Symptoms in Urban-Dwelling Older Adults

Shahirah Gillespie, MPH, Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA

Michael T. LeVasseur, PhD, MPH, Center for Health Incentives and Behavioural Economics (CHIBE), University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Yvonne L. Michael*, ScD, SM, Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA

* Corresponding author: [email protected]

Michael T. LeVasseur, PhD, MPH, Center for Health Incentives and Behavioural Economics (CHIBE), University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Yvonne L. Michael*, ScD, SM, Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA

* Corresponding author: [email protected]

SUMMARY OF PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

The current findings support public policy to promote neighbourhoods with dynamic and diverse amenities to maintain the mental health and reduce the prevalence of depression in older adults. This is particularly important for older adults with optimal mobility. Further, interventions should be devised that increase mobility and life space among older adults.

The current findings support public policy to promote neighbourhoods with dynamic and diverse amenities to maintain the mental health and reduce the prevalence of depression in older adults. This is particularly important for older adults with optimal mobility. Further, interventions should be devised that increase mobility and life space among older adults.

Abstract

Objective: Adults living in poorer neighbourhoods are at increased risk of developing depression, possibly as a result of disproportionate exposure to stressors and limited access to beneficial resources in the immediate neighbourhood. The aims of this paper were to assess the association between amenity diversity in urban neighbourhoods and depression in older adults, and to evaluate how this effect was modified by older adult mobility.

Methods: This cross-sectional study used data from a random digit dial sample of community-dwelling older adults in Philadelphia, PA (age range: 65-98, n=658). Amenity diversity was assessed using the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Neighbourhood Development (LEED-ND) index for participants’ neighbourhoods (census tracts = 276). Mobility was assessed using the Life-Space Assessment (LSA), which quantified the distance and frequency individuals moved past their bedroom and home within the past month. Depressive symptoms were measured using the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D); those with 4 or more symptoms were categorised as having symptoms of depression.

Results: We found a population prevalence of depression of 14%. Mobility significantly modified association between amenity, diversity and depression. After adjustment for factors such as: age, sex, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, smoking, and income among high mobility older adults living in low amenity and moderate amenity neighbourhoods were more likely to have symptoms of depression compared to people living in high neighbourhood amenity neighbourhoods (Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval: 5.75, 1.14 – 28.91, 3.93, 0.80-19.19, respectively). Neighbourhood amenity diversity was not associated with depression among low mobility older adults.

Conclusion: The findings support public policy to promote neighbourhoods with diverse amenities as a means to support mental health in older adults.

Objective: Adults living in poorer neighbourhoods are at increased risk of developing depression, possibly as a result of disproportionate exposure to stressors and limited access to beneficial resources in the immediate neighbourhood. The aims of this paper were to assess the association between amenity diversity in urban neighbourhoods and depression in older adults, and to evaluate how this effect was modified by older adult mobility.

Methods: This cross-sectional study used data from a random digit dial sample of community-dwelling older adults in Philadelphia, PA (age range: 65-98, n=658). Amenity diversity was assessed using the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Neighbourhood Development (LEED-ND) index for participants’ neighbourhoods (census tracts = 276). Mobility was assessed using the Life-Space Assessment (LSA), which quantified the distance and frequency individuals moved past their bedroom and home within the past month. Depressive symptoms were measured using the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D); those with 4 or more symptoms were categorised as having symptoms of depression.

Results: We found a population prevalence of depression of 14%. Mobility significantly modified association between amenity, diversity and depression. After adjustment for factors such as: age, sex, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, smoking, and income among high mobility older adults living in low amenity and moderate amenity neighbourhoods were more likely to have symptoms of depression compared to people living in high neighbourhood amenity neighbourhoods (Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval: 5.75, 1.14 – 28.91, 3.93, 0.80-19.19, respectively). Neighbourhood amenity diversity was not associated with depression among low mobility older adults.

Conclusion: The findings support public policy to promote neighbourhoods with diverse amenities as a means to support mental health in older adults.

| Full text PDF: Neighborhood amenities and depressive symptoms in older adults |

Introduction

Depression is the most common form of mental illness and its prevalence is projected to increase (CDC, 2013a). Older adults are at an increased risk for developing depression, as they are more prone to chronic health complications and mobility restrictions, which act as stressors and have the potential to destabilise their mental health (CDC, 2013b). Despite the importance of understanding risk factors for depression in older adults, they are generally left out of studies on mental health (Aneshensel et al., 2007; Cairney & Krause, 2004; Fiske, Wetherell, & Gatz, 2009; Galea et al., 2007).

Neighbourhood factors may be important independent contributors to the etiology of depression (Kim, 2008; Mair et al., 2008). Research consistently demonstrates an inverse relationship between mental health and individual, as well as neighbourhood-level socioeconomic status (Back & Lee, 2011; Galea et al., 2007; Kim, 2008). The ‘differential vulnerability’ theory suggests that adults living in poorer neighbourhoods are at increased risk of developing depression, possibly as a result of disproportionate exposure to stressors and limited access to beneficial resources in the immediate neighbourhood (Galea et al., 2007). Neighbourhood poverty is inversely associated with quantity and quality of neighbourhood amenities, as fewer businesses are willing to invest in low-income environments (Williams, 1999). Neighbourhoods with high poverty rates are more likely to have significant structural decay, poorly built environments, and a lack of important amenities (Kim, 2008; Ming Wen, Browning, & Cagney, 2007). Neighbourhood amenity diversity reflects a range of resources available to those living in a neighbourhood.

The greater the diversity of amenities in a neighbourhood, the more exposure individuals have to resources that support a stable lifestyle.

The presence of amenities in an older adults’ immediate neighbourhood is associated with mobility (Rosso et al., 2013a; Yeom, Fleury, & Keller, 2008). Amenities associated with greater mobility among older adults include food retail, such as chain grocery stores and farmers markets; services, consisting of banks, restaurants and gyms; community-serving retail, like pharmacies and convenient stores; and civic and community facilities, such as community or senior centres, medical clinics, public parks, and police stations (Rosso et al., 2013a). Studies of neighbourhood amenities typically focus on the quantity of the built environment within a neighbourhood (Clarke & Nieuwenhuijsen, 2009; Kim, 2008). However, a greater quantity of amenities does not ensure a high diversity of amenities. In fact, the repeated occurrence of similar resources in proximity may not have significant benefits to the neighbourhood. In some cases, this repetition was a detrimental factor leading to poor health outcomes (Brown et al., 2008).

Optimal mobility, defined as the “relative ease and freedom of movement in all of its forms”, is central to healthy ageing (Satariano et al., 2012). When mobility is severely restricted, older adults may experience limited exposure to neighbourhood amenities, thus creating a barrier to sustaining their mental health. The association between mobility and neighbourhood amenities may be reciprocal. Consistent with a relational approach to place and health, older adults’ mobility may also be influenced by their perceptions of their neighbourhood environment (Amarantos, Martinez, & Dwyer, 2001; Beard et al., 2009; Berke et al., 2007; Rosso et al., 2013a; Vallee et al., 2011). Undesirable neighbourhood characteristics could include a lack of amenities, social disorder or infrastructural decay (Beard et al., 2009; Kim, 2008). Older adults living in high stress neighbourhoods may limit their mobility to avoid their perceived problems with the neighbourhood environment (Shumway-Cook et al., 2003), thus further reducing access to critical amenities that support stable mental health.

The goal of the current research was to evaluate the association between neighbourhood amenities and mental health in adults over the age of 65 living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. We hypothesised that those living in areas with low diversity of amenities were at an increased risk of depression compared to adults living in neighbourhoods with greater amenity diversity. Further, we examined how this association was modified by older adults’ mobility.

Methods

The Life Space Mobility in Older Adults survey is a sub-study of the Household Health Survey, a biennial, population-based survey of South-eastern Pennsylvania conducted by the Public Health Management Corporation. The sub-study was conducted in 2010 among participants aged 65 and older in the city of Philadelphia (n=675) with a participation proportion of 74.1% (Rosso et al., 2013a). The study sample for the current analysis excluded participants missing data smoking status (n=3), race/ethnicity (n=11) and highest level of education (n=3) for a final study sample of 658.

Measures

To calculate neighbourhood amenity diversity, neighbourhoods were defined by census tract as defined by the 2010 US Census and American Community Survey (census tracts = 276). The definition for amenity diversity was adapted from Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design-Neighbourhood Development criteria (LEED-ND) (US Green Building Council, 2009). Four categories of amenity were defined based on LEED-ND and included: 1) food retail—supermarket, farmers market, other food store with produce; 2) community-serving retail—clothing store, hardware store, pharmacy, etc.; 3) services—bank, gym or health club, laundry or dry cleaner, etc.; and 4) civic and community facilities—senior or child care, community centre, educational facility, places of worship, etc. Amenities were geocoded using data from the 2010 Esri Business Analyst database (Esri, Inc., Redlands, California) and classified based on the 9-digit North American Industry Classification System codes. Using the LEED-ND algorithm, up to 2 occurrences of any single amenity was counted and then summed across each of the 27 amenity types resulting in a scale that ranged from 0 to 54. Neighbourhood amenity diversity was categorised into three categories, each containing a third of the population, representing low diversity (amenity score less than or equal to 17), moderate diversity (amenity score between 18 and 24), and high diversity (amenity score greater than or equal to 25).

Mobility was assessed using a modified version of the Life-Space Assessment (LSA). The LSA was designed to measure achieved function and incorporates aspects of mobility beyond the ability to walk (Peel et al., 2005). The LSA score assess mobility in the past month over five levels of increasing distance: 1) home, 2) areas immediately outside of the home, 3) neighbourhood, 4) city beyond neighbourhood, and 5) beyond the city. In the modified version used for the current study, the second level of LSA was excluded as this level lacks relevance to many urban residents. For each of the 4 remaining levels, participants provide information about how frequently they travelled to that area and whether they needed assistance from another person or from equipment. Scores for distance travelled, frequency travelled and need for assistance were totalled to create an overall score. In prior research validating the modified version of the LSA, we reported that overall score was the most highly correlated with physical performance (Rosso et al., 2013b). Confirmatory validity and reliability have been established in this population of older adults (Rosso et al., 2013b). Internal consistency of the modified LSA was adequate (α=0.77). Total scores ranged from 0 – 104, with higher scores indicating greater mobility.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Respondents were asked to indicate yes or no to the following questions (about feelings in the previous week): (a) I felt depressed, (b) I felt that everything I did was an effort, (c) My sleep was restless, (d) I was happy, (e) I felt lonely, (f) People were unfriendly, (g) I enjoyed life, (h) I felt sad, (i) I felt that people disliked me, and (j) I could not get going. Respondents indicating 4 or more symptoms were identified as depressed. The reliability and validity of this scale and this cut-off point for depression was well established for older adult populations (Irwin, Artin, & Oxman, 1999).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for main effects and potential confounders. Bivariate analyses of these statistics were conducted examining their relationship with category of neighbourhood amenity (low, moderate, high). P-values for categorical values were obtained using the Kruskal Wallis test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to obtain p-values for continuous variables.

Logistic regression was used to assess the association between categories of neighbourhood amenity and presence of depression, as indicated by 4 or more symptoms. Confounders in the adjusted models included age, sex, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, smoking status, and income. Statistical significance was set at .05 for assessing main effects.

Given the low level of missing data on key confounders (2.5% for race/ethnicity, education, and smoking), we conducted a complete case analysis. However, 175 (26.6%) of respondents were missing data on income. Given the potential for income being an important confounder in this analysis, we used a missing data indicator to conduct these analyses. We also conducted two sensitivity analyses wherein missing values for income were set to either the minimum or maximum value to evaluate the influence of this approach to addressing the missing data.

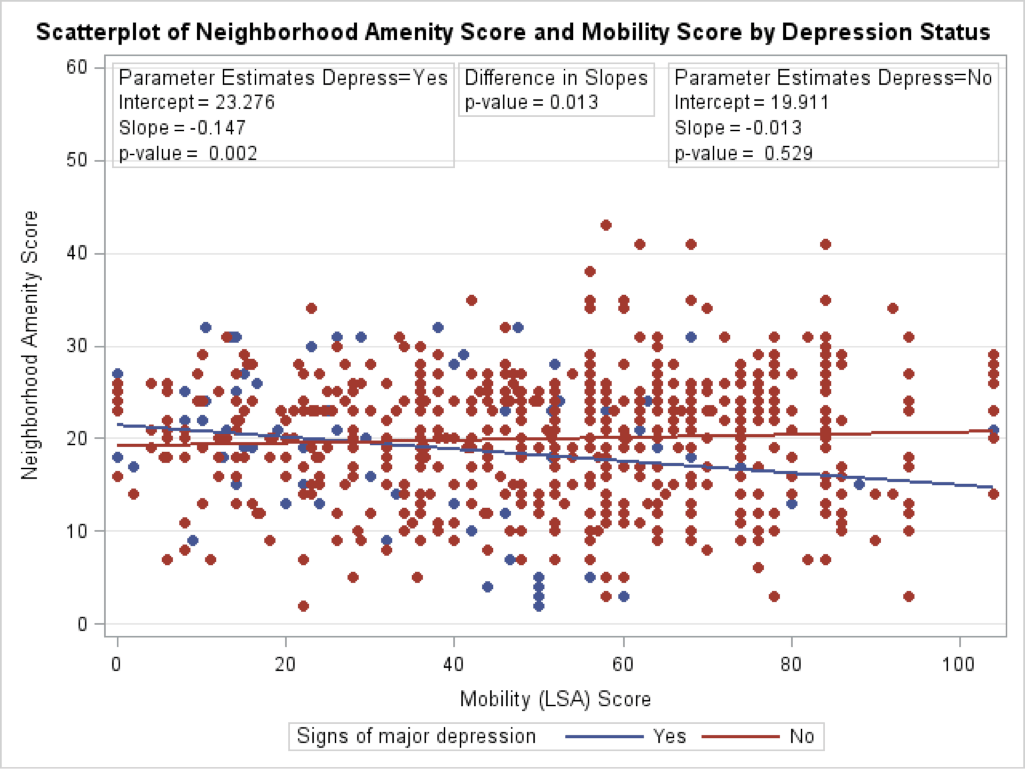

To test for the modifying effect of mobility status, we included a mobility*neighbourhood amenity interaction term in our models. In the presence of significant interaction, final results were stratified by mobility status dichotomised at the midpoint (median = 52) to represent “high” and “low” mobility and stratified ORs reported. To visualise the relation between mobility, neighbourhood amenity diversity, and depression, we plotted the risk of being classified as depressed or not depressed by amenity diversity and mobility score. All significance tests were 2-tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

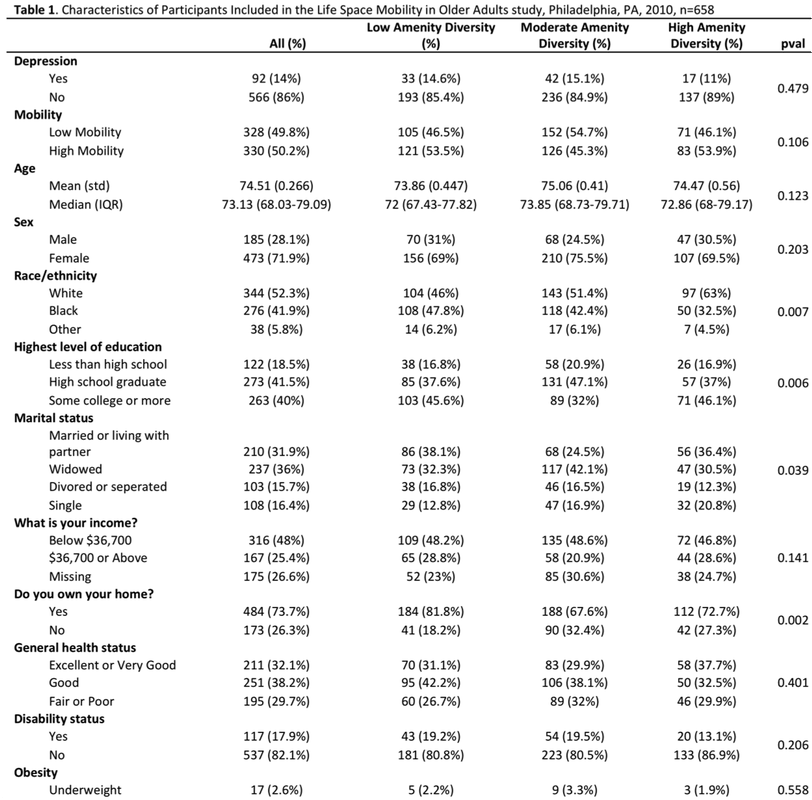

The mean age of the population was 74.5 (standard deviation, 0.3) years (Table 1). The population was primarily white or black race: 52% white, 42% black, and 6% other. The majority of the participants were female and had an education level of high school graduation or above. Almost 20% were disabled and 65% were overweight or obese. The prevalence of depression in this population was 14%. Participants living in neighbourhoods with greater amenity diversity were more likely to be white, single, higher level of education, and not homeowners.

Depression is the most common form of mental illness and its prevalence is projected to increase (CDC, 2013a). Older adults are at an increased risk for developing depression, as they are more prone to chronic health complications and mobility restrictions, which act as stressors and have the potential to destabilise their mental health (CDC, 2013b). Despite the importance of understanding risk factors for depression in older adults, they are generally left out of studies on mental health (Aneshensel et al., 2007; Cairney & Krause, 2004; Fiske, Wetherell, & Gatz, 2009; Galea et al., 2007).

Neighbourhood factors may be important independent contributors to the etiology of depression (Kim, 2008; Mair et al., 2008). Research consistently demonstrates an inverse relationship between mental health and individual, as well as neighbourhood-level socioeconomic status (Back & Lee, 2011; Galea et al., 2007; Kim, 2008). The ‘differential vulnerability’ theory suggests that adults living in poorer neighbourhoods are at increased risk of developing depression, possibly as a result of disproportionate exposure to stressors and limited access to beneficial resources in the immediate neighbourhood (Galea et al., 2007). Neighbourhood poverty is inversely associated with quantity and quality of neighbourhood amenities, as fewer businesses are willing to invest in low-income environments (Williams, 1999). Neighbourhoods with high poverty rates are more likely to have significant structural decay, poorly built environments, and a lack of important amenities (Kim, 2008; Ming Wen, Browning, & Cagney, 2007). Neighbourhood amenity diversity reflects a range of resources available to those living in a neighbourhood.

The greater the diversity of amenities in a neighbourhood, the more exposure individuals have to resources that support a stable lifestyle.

The presence of amenities in an older adults’ immediate neighbourhood is associated with mobility (Rosso et al., 2013a; Yeom, Fleury, & Keller, 2008). Amenities associated with greater mobility among older adults include food retail, such as chain grocery stores and farmers markets; services, consisting of banks, restaurants and gyms; community-serving retail, like pharmacies and convenient stores; and civic and community facilities, such as community or senior centres, medical clinics, public parks, and police stations (Rosso et al., 2013a). Studies of neighbourhood amenities typically focus on the quantity of the built environment within a neighbourhood (Clarke & Nieuwenhuijsen, 2009; Kim, 2008). However, a greater quantity of amenities does not ensure a high diversity of amenities. In fact, the repeated occurrence of similar resources in proximity may not have significant benefits to the neighbourhood. In some cases, this repetition was a detrimental factor leading to poor health outcomes (Brown et al., 2008).

Optimal mobility, defined as the “relative ease and freedom of movement in all of its forms”, is central to healthy ageing (Satariano et al., 2012). When mobility is severely restricted, older adults may experience limited exposure to neighbourhood amenities, thus creating a barrier to sustaining their mental health. The association between mobility and neighbourhood amenities may be reciprocal. Consistent with a relational approach to place and health, older adults’ mobility may also be influenced by their perceptions of their neighbourhood environment (Amarantos, Martinez, & Dwyer, 2001; Beard et al., 2009; Berke et al., 2007; Rosso et al., 2013a; Vallee et al., 2011). Undesirable neighbourhood characteristics could include a lack of amenities, social disorder or infrastructural decay (Beard et al., 2009; Kim, 2008). Older adults living in high stress neighbourhoods may limit their mobility to avoid their perceived problems with the neighbourhood environment (Shumway-Cook et al., 2003), thus further reducing access to critical amenities that support stable mental health.

The goal of the current research was to evaluate the association between neighbourhood amenities and mental health in adults over the age of 65 living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. We hypothesised that those living in areas with low diversity of amenities were at an increased risk of depression compared to adults living in neighbourhoods with greater amenity diversity. Further, we examined how this association was modified by older adults’ mobility.

Methods

The Life Space Mobility in Older Adults survey is a sub-study of the Household Health Survey, a biennial, population-based survey of South-eastern Pennsylvania conducted by the Public Health Management Corporation. The sub-study was conducted in 2010 among participants aged 65 and older in the city of Philadelphia (n=675) with a participation proportion of 74.1% (Rosso et al., 2013a). The study sample for the current analysis excluded participants missing data smoking status (n=3), race/ethnicity (n=11) and highest level of education (n=3) for a final study sample of 658.

Measures

To calculate neighbourhood amenity diversity, neighbourhoods were defined by census tract as defined by the 2010 US Census and American Community Survey (census tracts = 276). The definition for amenity diversity was adapted from Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design-Neighbourhood Development criteria (LEED-ND) (US Green Building Council, 2009). Four categories of amenity were defined based on LEED-ND and included: 1) food retail—supermarket, farmers market, other food store with produce; 2) community-serving retail—clothing store, hardware store, pharmacy, etc.; 3) services—bank, gym or health club, laundry or dry cleaner, etc.; and 4) civic and community facilities—senior or child care, community centre, educational facility, places of worship, etc. Amenities were geocoded using data from the 2010 Esri Business Analyst database (Esri, Inc., Redlands, California) and classified based on the 9-digit North American Industry Classification System codes. Using the LEED-ND algorithm, up to 2 occurrences of any single amenity was counted and then summed across each of the 27 amenity types resulting in a scale that ranged from 0 to 54. Neighbourhood amenity diversity was categorised into three categories, each containing a third of the population, representing low diversity (amenity score less than or equal to 17), moderate diversity (amenity score between 18 and 24), and high diversity (amenity score greater than or equal to 25).

Mobility was assessed using a modified version of the Life-Space Assessment (LSA). The LSA was designed to measure achieved function and incorporates aspects of mobility beyond the ability to walk (Peel et al., 2005). The LSA score assess mobility in the past month over five levels of increasing distance: 1) home, 2) areas immediately outside of the home, 3) neighbourhood, 4) city beyond neighbourhood, and 5) beyond the city. In the modified version used for the current study, the second level of LSA was excluded as this level lacks relevance to many urban residents. For each of the 4 remaining levels, participants provide information about how frequently they travelled to that area and whether they needed assistance from another person or from equipment. Scores for distance travelled, frequency travelled and need for assistance were totalled to create an overall score. In prior research validating the modified version of the LSA, we reported that overall score was the most highly correlated with physical performance (Rosso et al., 2013b). Confirmatory validity and reliability have been established in this population of older adults (Rosso et al., 2013b). Internal consistency of the modified LSA was adequate (α=0.77). Total scores ranged from 0 – 104, with higher scores indicating greater mobility.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Respondents were asked to indicate yes or no to the following questions (about feelings in the previous week): (a) I felt depressed, (b) I felt that everything I did was an effort, (c) My sleep was restless, (d) I was happy, (e) I felt lonely, (f) People were unfriendly, (g) I enjoyed life, (h) I felt sad, (i) I felt that people disliked me, and (j) I could not get going. Respondents indicating 4 or more symptoms were identified as depressed. The reliability and validity of this scale and this cut-off point for depression was well established for older adult populations (Irwin, Artin, & Oxman, 1999).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for main effects and potential confounders. Bivariate analyses of these statistics were conducted examining their relationship with category of neighbourhood amenity (low, moderate, high). P-values for categorical values were obtained using the Kruskal Wallis test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to obtain p-values for continuous variables.

Logistic regression was used to assess the association between categories of neighbourhood amenity and presence of depression, as indicated by 4 or more symptoms. Confounders in the adjusted models included age, sex, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, smoking status, and income. Statistical significance was set at .05 for assessing main effects.

Given the low level of missing data on key confounders (2.5% for race/ethnicity, education, and smoking), we conducted a complete case analysis. However, 175 (26.6%) of respondents were missing data on income. Given the potential for income being an important confounder in this analysis, we used a missing data indicator to conduct these analyses. We also conducted two sensitivity analyses wherein missing values for income were set to either the minimum or maximum value to evaluate the influence of this approach to addressing the missing data.

To test for the modifying effect of mobility status, we included a mobility*neighbourhood amenity interaction term in our models. In the presence of significant interaction, final results were stratified by mobility status dichotomised at the midpoint (median = 52) to represent “high” and “low” mobility and stratified ORs reported. To visualise the relation between mobility, neighbourhood amenity diversity, and depression, we plotted the risk of being classified as depressed or not depressed by amenity diversity and mobility score. All significance tests were 2-tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The mean age of the population was 74.5 (standard deviation, 0.3) years (Table 1). The population was primarily white or black race: 52% white, 42% black, and 6% other. The majority of the participants were female and had an education level of high school graduation or above. Almost 20% were disabled and 65% were overweight or obese. The prevalence of depression in this population was 14%. Participants living in neighbourhoods with greater amenity diversity were more likely to be white, single, higher level of education, and not homeowners.

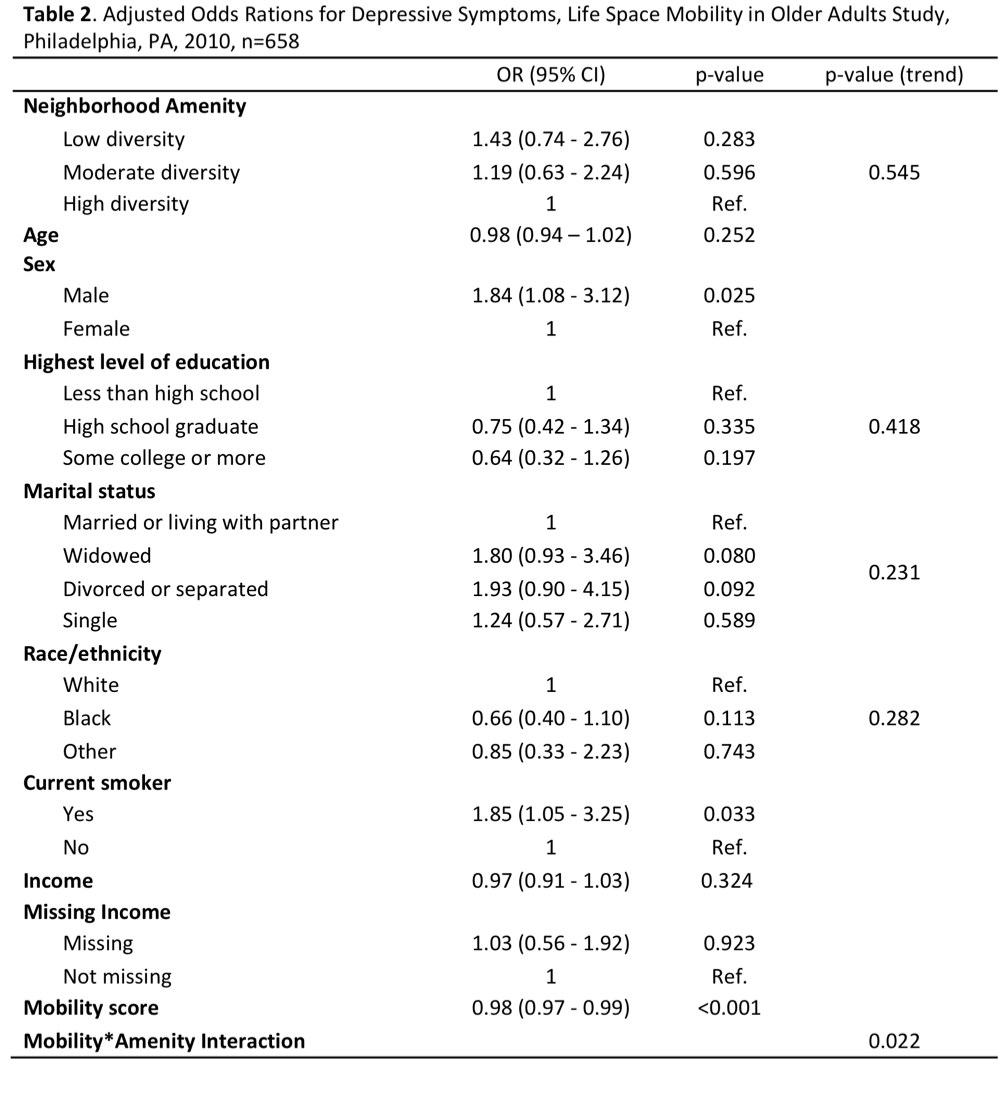

In this population of community-dwelling older adults, mobility was strongly associated with depression. Increasing mobility was associated with reduced odds of depression (p < 0.001). Being male and smoking were associated with increased odds of depression. After controlling for individual level factors, living in neighbourhoods with the lowest diversity of neighbourhood amenities was associated with a non-significant increase in depression compared with neighbourhoods with the highest diversity (OR=1.43, 95% CI: 0.74 - 2.76) (Table 2).

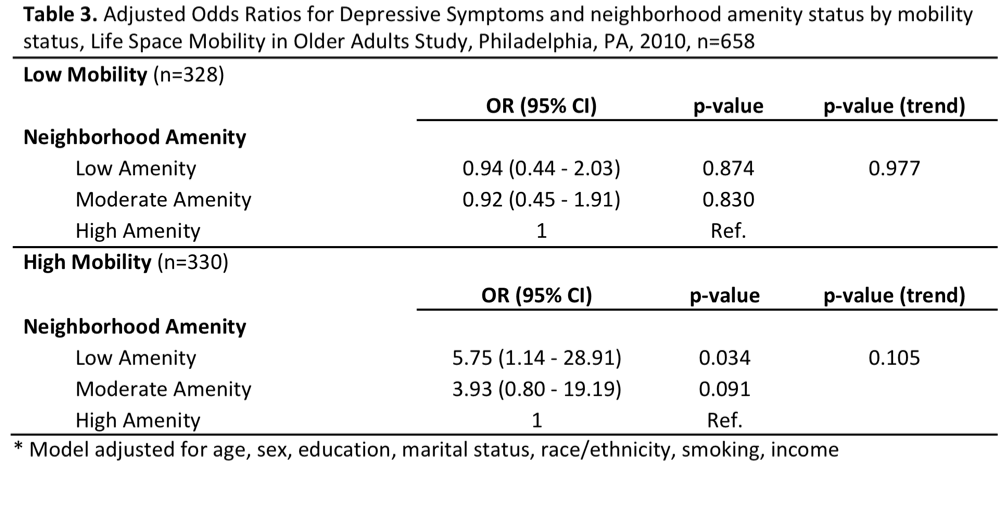

Mobility significantly modifies the association between neighbourhood amenity diversity and depression (p-value: 0.022). Table 3 provides the model results stratified by mobility status dichotomised at the median point to represent “high” and “low” mobility. Decreasing amenity diversity was associated with increasing risk for depression among older adults with high mobility (p-value for trend = 0.105). After adjustment for confounders, living in neighbourhoods with the lowest diversity of amenities was associated with almost a 6-fold increase in the odds of depression, compared with living in neighbourhoods with the highest diversity of amenities (OR=5.75, 95% CI: 1.14, 28.91). We observed no association between neighbourhood amenity diversity and depression among older adults with low mobility.

Figure 1 provides a visual summary of the unadjusted relation among mobility, neighbourhood amenity diversity, and depression status. We have estimated the risk of being classified as depressed or not depressed by mobility score and neighbourhood amenity diversity. Among older adults at the very low end of the mobility scale, those who were not depressed were more likely to live in a neighbourhood with slightly lower amenity diversity compared to those who were depressed. The association between depression and neighbourhood amenity diversity reverses above the mobility score of 30. Above that point, those who were not depressed were more likely to live in a neighbourhood with higher amenity diversity compared to those who were depressed when holding mobility score constant. The p-value for the difference in the two regression lines is 0.013.

Sensitivity analyses showed minimal change in the adjusted odds of depression by neighbourhood amenity score, when all missing values of income were set to the minimum or maximum values (data not shown).

Sensitivity analyses showed minimal change in the adjusted odds of depression by neighbourhood amenity score, when all missing values of income were set to the minimum or maximum values (data not shown).

Figure 1: Neighborhood amenity score and mobility score by depression status

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the association between neighbourhood amenity environments and depression was moderated by mobility status. Among older adults with higher mobility, poor neighbourhood amenity environments were associated with depression among older adults. We observed no association between neighbourhood amenity diversity and depression among older adults with limited mobility.

Restricted life-space mobility is well documented as a stressor on health status, leading to a poor health status when coupled with undesirable neighbourhood environments (Rosso, Auchincloss, & Michael, 2011; Vallee et al., 2011; Yeom et al., 2008). Research has also found that physical impairments are a risk factor for depression. Physical impairments are likely to limit an individual’s life-space mobility, and therefore they may experience more depression than an able-bodied individual (Gayman, Turner, & Cui, 2008; González et al., 2013; Simning et al., 2012). Physically impaired individuals may also have fewer social activities and a smaller social network and therefore may have limited access to neighbourhood amenities that facilitate social interaction, among other necessary and desirable benefits (Yeom et al., 2008, Rosso et al, 2013b).

Past research suggests that the effect of a poor neighbourhood’s environment on mental health is exacerbated with restricted life-space mobility; low quality built environments, including structural decay and dilapidated housing, have been found to lead to depressive symptoms, particularly among individuals who are more restricted to their residential neighbourhood (Melis et al., 2015, Vallee et al., 2011). In this study, the lack of diverse amenities within the neighbourhood was associated with depression among those older adults with greater mobility, i.e. the capacity to travel into the neighbourhood. Consistent with other findings in our study, amenity diversity was more relevant to older adults that engaged in regular walking behaviour, or had high mobility status (Nagel et al., 2008). Among those older adults with low mobility, we observed no difference in depression by amenity diversity. Older adults with restricted mobility may be less aware of the resources available (or not available) in their neighbourhood.

Future research should assess the perceptions of older adults on their neighbourhood environment. It is possible that low mobility individuals, regardless of neighbourhood amenity diversity, have a different perception of the environment due to their inability to access and assess the environment. Prior research has found that once older adults have internalised their deprived neighbourhood environment, they may be prone to deliberately limiting their life-space to avoid their perceived problems with the neighbourhood environment (Shumway-Cook et al., 2003). Less positive perceptions of the environment may reflect masked resentment for their isolation and restricted life-space. This may provide an opportunity for interventions to improve perceptions of neighbourhood environment as a mechanism to increase mobility and reduce depression. Additionally, research is needed to better understand the mechanisms through which exposure to neighbourhood amenities may influence depressive symptoms among those older adults who are mobile. Collecting additional data from older adults about how they use their neighbourhood and their experience with these amenities may help to identify the behavioural and cognitive processes linking neighbourhood environment to mental health (Kestins et al., 2016).

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. Our cross-sectional study design cannot evaluate causality. Future longitudinal studies can address this limitation. We were limited to information on amenities in the neighbourhood around the participants’ home residence. Exposure to other amenities within the participants’ full activity space would provide a more complete measure of exposure (Kestens et al., 2016). We were not able to control for dementia in our analyses. Dementia would impact people's ability to get out and about in their neighbourhoods and is a risk factor for depression. We also did not evaluate neighbourhood walkability and thus were unable evaluate whether this is a confounder or modifier of the association. Additionally, while some evidence suggests gender differences in the environmental risk factors for depression (Melis et al., 2015), we did not have sufficient sample size to stratify by sex. Finally, as the study was based on adults over 65 living in Philadelphia, our results may not be extrapolated to other cities or regions in the country.

Our findings suggest that the association between neighbourhood amenity environments and depression was moderated by mobility status. Among older adults with higher mobility, poor neighbourhood amenity environments were associated with depression among older adults. We observed no association between neighbourhood amenity diversity and depression among older adults with limited mobility.

Restricted life-space mobility is well documented as a stressor on health status, leading to a poor health status when coupled with undesirable neighbourhood environments (Rosso, Auchincloss, & Michael, 2011; Vallee et al., 2011; Yeom et al., 2008). Research has also found that physical impairments are a risk factor for depression. Physical impairments are likely to limit an individual’s life-space mobility, and therefore they may experience more depression than an able-bodied individual (Gayman, Turner, & Cui, 2008; González et al., 2013; Simning et al., 2012). Physically impaired individuals may also have fewer social activities and a smaller social network and therefore may have limited access to neighbourhood amenities that facilitate social interaction, among other necessary and desirable benefits (Yeom et al., 2008, Rosso et al, 2013b).

Past research suggests that the effect of a poor neighbourhood’s environment on mental health is exacerbated with restricted life-space mobility; low quality built environments, including structural decay and dilapidated housing, have been found to lead to depressive symptoms, particularly among individuals who are more restricted to their residential neighbourhood (Melis et al., 2015, Vallee et al., 2011). In this study, the lack of diverse amenities within the neighbourhood was associated with depression among those older adults with greater mobility, i.e. the capacity to travel into the neighbourhood. Consistent with other findings in our study, amenity diversity was more relevant to older adults that engaged in regular walking behaviour, or had high mobility status (Nagel et al., 2008). Among those older adults with low mobility, we observed no difference in depression by amenity diversity. Older adults with restricted mobility may be less aware of the resources available (or not available) in their neighbourhood.

Future research should assess the perceptions of older adults on their neighbourhood environment. It is possible that low mobility individuals, regardless of neighbourhood amenity diversity, have a different perception of the environment due to their inability to access and assess the environment. Prior research has found that once older adults have internalised their deprived neighbourhood environment, they may be prone to deliberately limiting their life-space to avoid their perceived problems with the neighbourhood environment (Shumway-Cook et al., 2003). Less positive perceptions of the environment may reflect masked resentment for their isolation and restricted life-space. This may provide an opportunity for interventions to improve perceptions of neighbourhood environment as a mechanism to increase mobility and reduce depression. Additionally, research is needed to better understand the mechanisms through which exposure to neighbourhood amenities may influence depressive symptoms among those older adults who are mobile. Collecting additional data from older adults about how they use their neighbourhood and their experience with these amenities may help to identify the behavioural and cognitive processes linking neighbourhood environment to mental health (Kestins et al., 2016).

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. Our cross-sectional study design cannot evaluate causality. Future longitudinal studies can address this limitation. We were limited to information on amenities in the neighbourhood around the participants’ home residence. Exposure to other amenities within the participants’ full activity space would provide a more complete measure of exposure (Kestens et al., 2016). We were not able to control for dementia in our analyses. Dementia would impact people's ability to get out and about in their neighbourhoods and is a risk factor for depression. We also did not evaluate neighbourhood walkability and thus were unable evaluate whether this is a confounder or modifier of the association. Additionally, while some evidence suggests gender differences in the environmental risk factors for depression (Melis et al., 2015), we did not have sufficient sample size to stratify by sex. Finally, as the study was based on adults over 65 living in Philadelphia, our results may not be extrapolated to other cities or regions in the country.

References

Amarantos, Eleni, Martinez, Andrea, & Dwyer, Johanna. (2001). Nutrition and quality of life in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, 56A, 54-64. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.54

Aneshensel, Carol S., Wight, Richard G., Miller-Martinez, Dana, Botticello, Amanda L., Karlamangla, Arun S., & Seeman, Teresa E. (2007). Urban neighborhoods and depressive symptoms among older adults. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 62(1), S52-S59. doi: Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/210106841?accountid=10559

Back, Joung Hwan, & Lee, Yunhwan. (2011). Gender differences in the association between socioeconomic status (SES) and depressive symptoms in older adults. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 52(3), e140-e144. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.09.012

Beard, J. R., Blaney, S., Cerda, M., Frye, V., Lovasi, G. S., Ompad, D., Vlahov, D. (2009). Neighborhood characteristics and disability in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 64(2), 252-257. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn018

Berke, E. M., Koepsell, T. D., Moudon, A. V., Hoskins, R. E., & Larson, E. B. (2007). Association of the built environment with physical activity and obesity in older persons. American journal of public health, 97(3), 486-492.

Brown, Arleen F., Vargas, Roberto B., Ang, Alfonso, & Pebley, Anne R. (2008). The Neighborhood Food Resource Environment and the Health of Residents with Chronic Conditions: The Food Resource Environment and the Health of Residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(8), 1137-1144. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0601-5

Cairney, J., & Krause, N. (2004). The social distribution of psychological distress and depression in older adults. GERONTOLOGIST, 44(1), 286-286. doi: 10.1177/0898264305280985

CDC. (2013a). Mental Health: Mental Health Basics.

CDC. (2013b). Healthy Aging: Depression is Not a Normal Part of Growing Older.

Clarke, P., & Nieuwenhuijsen, E. R. (2009). Environments for healthy ageing: a critical review. Maturitas, 64(1), 14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.07.011

Fiske, Amy, Wetherell, Julie Loebach, & Gatz, Margaret. (2009). Depression in Older Adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5(1), 363-389. doi: doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621

Galea, Sandro, Ahern, Jennifer, Nandi, Arijit, Tracy, Melissa, Beard, John, & Vlahov, David. (2007). Urban Neighborhood Poverty and the Incidence of Depression in a Population-Based Cohort Study. Annals of Epidemiology, 17(3), 171-179. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.008

Gayman, M. D., Turner, R. J., & Cui, M. (2008). Physical limitations and depressive symptoms: exploring the nature of the association. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 63(4), S219-S228.

González, Bertha C. S., Delgado, Leticia H., Quevedo, Juana E. C., & Gallegos Cabriales, Esther C. (2013). Life-Space Mobility, Perceived Health, and Depression Symptoms in a Sample of Mexican Older Adults. Hispanic Health Care International, 11(1), 14. doi: Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1373488151?accountid=10559

Irwin, M., Artin, K. H., & Oxman, M. N. (1999). Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Archives of internal medicine, 159(15), 1701-1704.

Kestens, Y., Chaix, B., Shareck, M., & Vallée, J. (2016). Comments on Melis et al. The Effects of the Urban Built Environment on Mental Health: A Cohort Study in a Large Northern Italian City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2015, 12, 14898–14915. International journal of environmental research and public health, 13(3), 250.

Kim, D. (2008). Blues from the neighborhood? Neighborhood characteristics and depression. Epidemiol Rev, 30, 101-117. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn009

Kubzansky, L. D., Subramanian, S. V., Kawachi, I., Fay, M. E., Soobader, M.- J., & Berkman, L. F. (2005). Neighborhood contextual influences on depressive symptoms in the elderly. American journal of epidemiology, 162(3), 253-260. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi185

Mair, C., Diez Roux, A. V., & Galea, S. (2008). Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health, 62(11), 940-946, 948 p following 946. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.066605

Marshall SW. Power for tests of interaction: effect of raising the Type I error rate. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2007;4:4.

Melis, G., Gelormino, E., Marra, G., Ferracin, E., & Costa, G. (2015). The effects of the urban built environment on mental health: A cohort study in a large northern Italian city. International journal of environmental research and public health, 12(11), 14898-14915.

Ming Wen, Browning, Christopher R., & Cagney, Kathleen A. (2007). Neighbourhood Deprivation, Social Capital and Regular Exercise during Adulthood: A Multilevel Study in Chicago. Urban Studies, 44(13), 2651-2671. doi: 10.1080/00420980701558418

Nagel, C. L., Carlson, N. E., Bosworth, M., & Michael, Y. L. (2008). The relation between neighborhood built environment and walking activity among older adults. Am J Epidemiol, 168(4), 461-468. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn158

Peel, C., Baker, P. S., Roth, D. L., Brown, C. J., Bodner, E. V., & Allman, R. M. (2005). Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Physical therapy, 85(10), 1008-1019.

Rosso, A. L., Grubesic, T. H., Auchincloss, A. H., Tabb, L. P., & Michael, Y. L. (2013a). Neighborhood Amenities and Mobility in Older Adults. Am J Epidemiol. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt032

Rosso, A. L., Taylor, J. A., Tabb, L. P., & Michael, Y. L. (2013b). Mobility, disability, and social engagement in older adults. Journal of aging and health, 25(4), 617-637.

Rosso, A. L., Auchincloss, A. H., & Michael, Y. L. (2011). The urban built environment and mobility in older adults: a comprehensive review. Journal of aging research, 2011, 816106-816110. doi: 10.4061/2011/816106

Satariano, William A., Guralnik, Jack M., Jackson, Richard J., Marottoli, Richard A., Phelan, Elizabeth A., & Prohaska, Thomas R. (2012). Mobility and aging: new directions for public health action. American journal of public health, 102(8), 1508-1515. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300631

Shumway-Cook, Anne, Patla, Aftab, Stewart, Anita, Ferrucci, Luigi, Ciol, Marcia A., & Guralnik, Jack M. (2003). Environmental Components of Mobility Disability in Community-Living Older Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(3), 393-398. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51114.x

Simning, Adam, van Wijngaarden, Edwin, Fisher, Susan G., Richardson, Thomas M., & Conwell, Yeates. (2012). Mental healthcare need and service utilization in older adults living in public housing. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(5), 441-451. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31822003a7

U.S. Green Building Council. Green neighborhood development : LEED reference guide for neighborhood development. Washington, DC: U.S. Green Building Council; 2009.

Vallee, J., Cadot, E., Roustit, C., Parizot, I., & Chauvin, P. (2011). The role of daily mobility in mental health inequalities: the interactive influence of activity space and neighbourhood of residence on depression. Soc Sci Med, 73(8), 1133-1144. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.009

Williams, D.R. (1999). Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Health: The Added Effects of Racism and Discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 173-188.

Yeom, H. A., Fleury, J., & Keller, C. (2008). Risk factors for mobility limitation in community-dwelling older adults: a social ecological perspective. Geriatr Nurs, 29(2), 133-140. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.07.002

Amarantos, Eleni, Martinez, Andrea, & Dwyer, Johanna. (2001). Nutrition and quality of life in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, 56A, 54-64. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.54

Aneshensel, Carol S., Wight, Richard G., Miller-Martinez, Dana, Botticello, Amanda L., Karlamangla, Arun S., & Seeman, Teresa E. (2007). Urban neighborhoods and depressive symptoms among older adults. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 62(1), S52-S59. doi: Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/210106841?accountid=10559

Back, Joung Hwan, & Lee, Yunhwan. (2011). Gender differences in the association between socioeconomic status (SES) and depressive symptoms in older adults. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 52(3), e140-e144. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.09.012

Beard, J. R., Blaney, S., Cerda, M., Frye, V., Lovasi, G. S., Ompad, D., Vlahov, D. (2009). Neighborhood characteristics and disability in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 64(2), 252-257. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn018

Berke, E. M., Koepsell, T. D., Moudon, A. V., Hoskins, R. E., & Larson, E. B. (2007). Association of the built environment with physical activity and obesity in older persons. American journal of public health, 97(3), 486-492.

Brown, Arleen F., Vargas, Roberto B., Ang, Alfonso, & Pebley, Anne R. (2008). The Neighborhood Food Resource Environment and the Health of Residents with Chronic Conditions: The Food Resource Environment and the Health of Residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(8), 1137-1144. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0601-5

Cairney, J., & Krause, N. (2004). The social distribution of psychological distress and depression in older adults. GERONTOLOGIST, 44(1), 286-286. doi: 10.1177/0898264305280985

CDC. (2013a). Mental Health: Mental Health Basics.

CDC. (2013b). Healthy Aging: Depression is Not a Normal Part of Growing Older.

Clarke, P., & Nieuwenhuijsen, E. R. (2009). Environments for healthy ageing: a critical review. Maturitas, 64(1), 14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.07.011

Fiske, Amy, Wetherell, Julie Loebach, & Gatz, Margaret. (2009). Depression in Older Adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5(1), 363-389. doi: doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621

Galea, Sandro, Ahern, Jennifer, Nandi, Arijit, Tracy, Melissa, Beard, John, & Vlahov, David. (2007). Urban Neighborhood Poverty and the Incidence of Depression in a Population-Based Cohort Study. Annals of Epidemiology, 17(3), 171-179. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.008

Gayman, M. D., Turner, R. J., & Cui, M. (2008). Physical limitations and depressive symptoms: exploring the nature of the association. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 63(4), S219-S228.

González, Bertha C. S., Delgado, Leticia H., Quevedo, Juana E. C., & Gallegos Cabriales, Esther C. (2013). Life-Space Mobility, Perceived Health, and Depression Symptoms in a Sample of Mexican Older Adults. Hispanic Health Care International, 11(1), 14. doi: Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1373488151?accountid=10559

Irwin, M., Artin, K. H., & Oxman, M. N. (1999). Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Archives of internal medicine, 159(15), 1701-1704.

Kestens, Y., Chaix, B., Shareck, M., & Vallée, J. (2016). Comments on Melis et al. The Effects of the Urban Built Environment on Mental Health: A Cohort Study in a Large Northern Italian City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2015, 12, 14898–14915. International journal of environmental research and public health, 13(3), 250.

Kim, D. (2008). Blues from the neighborhood? Neighborhood characteristics and depression. Epidemiol Rev, 30, 101-117. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn009

Kubzansky, L. D., Subramanian, S. V., Kawachi, I., Fay, M. E., Soobader, M.- J., & Berkman, L. F. (2005). Neighborhood contextual influences on depressive symptoms in the elderly. American journal of epidemiology, 162(3), 253-260. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi185

Mair, C., Diez Roux, A. V., & Galea, S. (2008). Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health, 62(11), 940-946, 948 p following 946. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.066605

Marshall SW. Power for tests of interaction: effect of raising the Type I error rate. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2007;4:4.

Melis, G., Gelormino, E., Marra, G., Ferracin, E., & Costa, G. (2015). The effects of the urban built environment on mental health: A cohort study in a large northern Italian city. International journal of environmental research and public health, 12(11), 14898-14915.

Ming Wen, Browning, Christopher R., & Cagney, Kathleen A. (2007). Neighbourhood Deprivation, Social Capital and Regular Exercise during Adulthood: A Multilevel Study in Chicago. Urban Studies, 44(13), 2651-2671. doi: 10.1080/00420980701558418

Nagel, C. L., Carlson, N. E., Bosworth, M., & Michael, Y. L. (2008). The relation between neighborhood built environment and walking activity among older adults. Am J Epidemiol, 168(4), 461-468. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn158

Peel, C., Baker, P. S., Roth, D. L., Brown, C. J., Bodner, E. V., & Allman, R. M. (2005). Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Physical therapy, 85(10), 1008-1019.

Rosso, A. L., Grubesic, T. H., Auchincloss, A. H., Tabb, L. P., & Michael, Y. L. (2013a). Neighborhood Amenities and Mobility in Older Adults. Am J Epidemiol. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt032

Rosso, A. L., Taylor, J. A., Tabb, L. P., & Michael, Y. L. (2013b). Mobility, disability, and social engagement in older adults. Journal of aging and health, 25(4), 617-637.

Rosso, A. L., Auchincloss, A. H., & Michael, Y. L. (2011). The urban built environment and mobility in older adults: a comprehensive review. Journal of aging research, 2011, 816106-816110. doi: 10.4061/2011/816106

Satariano, William A., Guralnik, Jack M., Jackson, Richard J., Marottoli, Richard A., Phelan, Elizabeth A., & Prohaska, Thomas R. (2012). Mobility and aging: new directions for public health action. American journal of public health, 102(8), 1508-1515. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300631

Shumway-Cook, Anne, Patla, Aftab, Stewart, Anita, Ferrucci, Luigi, Ciol, Marcia A., & Guralnik, Jack M. (2003). Environmental Components of Mobility Disability in Community-Living Older Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(3), 393-398. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51114.x

Simning, Adam, van Wijngaarden, Edwin, Fisher, Susan G., Richardson, Thomas M., & Conwell, Yeates. (2012). Mental healthcare need and service utilization in older adults living in public housing. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(5), 441-451. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31822003a7

U.S. Green Building Council. Green neighborhood development : LEED reference guide for neighborhood development. Washington, DC: U.S. Green Building Council; 2009.

Vallee, J., Cadot, E., Roustit, C., Parizot, I., & Chauvin, P. (2011). The role of daily mobility in mental health inequalities: the interactive influence of activity space and neighbourhood of residence on depression. Soc Sci Med, 73(8), 1133-1144. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.009

Williams, D.R. (1999). Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Health: The Added Effects of Racism and Discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 173-188.

Yeom, H. A., Fleury, J., & Keller, C. (2008). Risk factors for mobility limitation in community-dwelling older adults: a social ecological perspective. Geriatr Nurs, 29(2), 133-140. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.07.002

About the Authors

|

Shahirah Gillespie is a community resiliency consultant and community-based health educator for the Western New York region. She received her Bachelor’s degree from Amherst College, majoring in Biology and Psychology, and received a John Woodruff Simpson Fellowship. After graduating with a Master’s degree in Public Health from Drexel University, studying trauma-informed care practices, she researched as a Samuel S. Fels Fellow for the Philadelphia Hoarding Task Force. In Buffalo, NY she founded a teen empowerment program focused on-hands on nutrition and hydration education and community role-modelling. Her research interests include: toxic stress and chronic trauma, food deserts and the built environment, ethnic-specific resilience strategies and mindfulness. Contact her @SocialEnergyMiners

|

|

Michael T. LeVasseur received his BA from Sarah Lawrence College where he had concentrations in Molecular Biology and Medical Anthropology, his MPH from CUNY Hunter College in the Epidemiology and Biostatistics track, and his PhD in Epidemiology from the Drexel University Dornsife School of Public Health. His research interests include sexual health, HIV infection, health disparities, and big data. His methodological interests include latent class analysis, data linkage, and missing data issues.

|

|

Yvonne L. Michael is a professor of epidemiology and co-director of the Center for Health and the Designed Environment at Drexel University, a member of the AIA Design and Health Consortium. The goal of the center is to advance basic research on how the designed environment and urban living conditions affect public health through new translational research; engaged community outreach with professional communities, neighborhood communities and University communities through targeted symposiums and events; and training of the next generation of practitioners and researchers through interdisciplinary courses and program offerings.

|