|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2016;1:6

|

The digitalization of traumascapes

Digital technology and social media can help urban planners and designers to understand and heal traumascapes

Sophie Gleizes

European Commission and Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health

European Commission and Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health

Introduction

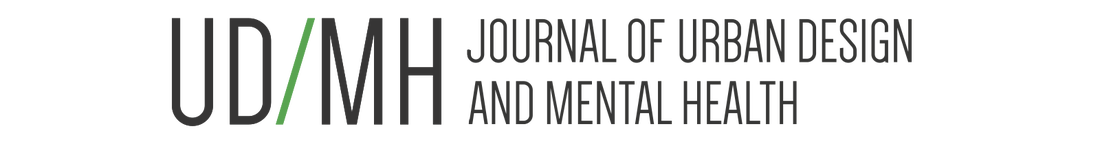

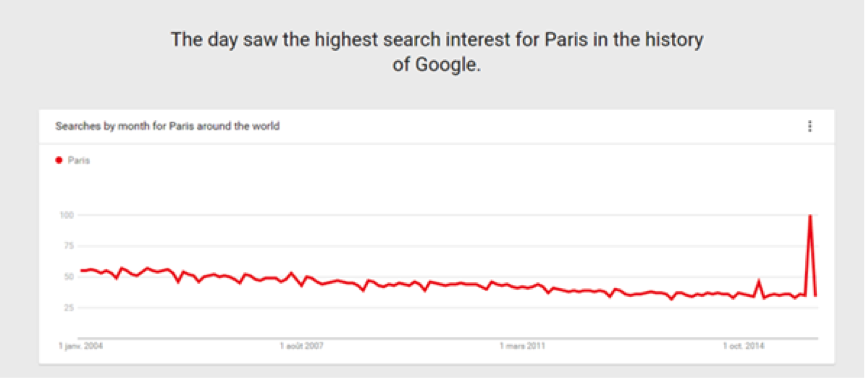

After terror attacks or other catastrophic events, an overwhelming number of people are increasingly sharing their experiences and concerns, and expressing their solidarity, via the Internet. The high frequency of social media activity correlated to events such as the recent Paris attacks (Fig 1 and 2) has provided us with a sense of the potential of gaining knowledge that could help us understand the mental processes at work when people are dealing with their reactions associated with locations where something traumatic has occurred, also known as ‘traumascapes’.

After terror attacks or other catastrophic events, an overwhelming number of people are increasingly sharing their experiences and concerns, and expressing their solidarity, via the Internet. The high frequency of social media activity correlated to events such as the recent Paris attacks (Fig 1 and 2) has provided us with a sense of the potential of gaining knowledge that could help us understand the mental processes at work when people are dealing with their reactions associated with locations where something traumatic has occurred, also known as ‘traumascapes’.

Fig 1 Google Trends: visualisation of a peak in the frequency of search activity after the attack in Paris

Fig 2: How the world used digital search tools to understand what happened in the Paris attacks

The democratization of tools such as smartphones and tablets, and the digital media streams they produce, has accelerated the production of an "augmented urbanity". It has been over a decade since scholars and architects have really started to leverage digital technology and social media in their urban research, but this is still a developing field. Lev Manovitch, through his Big Data Lab, hails the promising insights that the analysis of these massive, ready-made data streams can provide when approaching human behavior and urban systems. Today, there exists a fuzzy, dense and interactive virtual space running parallel to physical cities that harbours perhaps infinite insight potential for researchers.

In a context where cities are both nodes of intense social media activity and potential targets of human and natural catastrophes, the question is therefore: how can we extract meaningful information by observing more carefully these vibrant data streams? With the virtual space becoming particularly active when a location-specific incident occurs, is it possible to leverage social media input to become more sensitive and conscious about existing or potential traumascapes in our cities?

Coordination and solidarity

Digital technology has already proved useful both during and in the aftermath of a crisis in understanding and responding to urges and needs, or in reflecting on ways of remembering spaces as complex as traumascapes. Social media networks can facilitate coordination as well as expression of solidarity in response to a crisis, as shown by the hashtag #PorteOuverte (Open Door) in Paris used by residents offering refuge during the lockdown induced by the terror attacks of 13th November, 2015. Another example is the controversial "safety check" tool, which transformed Facebook into a crisis information network for people willing to reassure their contacts of their safety.

A collective space for emotional expression and support

In addition to facilitating the practicalities of coping with an event during a crisis and its direct aftermath, social media offers a platform to project emotions and manifest a form of engagement onto a virtual space. Indeed, we can observe that intense collective and individual emotions both produce and impact space. They occur simultaneously in the physical and virtual public space, as shown by the production of spontaneous on-site memorials and the spread of hashtags. This happens in a context where city dwellers have increasingly engaged with urban space by liking, sharing or commenting on a geolocalisation or picture of a place. By doing so, individuals can enrich the virtual space with their emotional data, by associating emotions to local coordinates. Tagging oneself or one’s emotions on a virtual place is a 2.0 version of graffiti tagging a material space: such practices can be infinitely replicated without leaving direct physical traces, allowing people geographically far to occupy and engage with the site.

Enriching perceptions of the city

Interestingly enough, the city itself often appears to be perceived as the victim and the subject of resilience after a crisis. Following the Paris attacks, numerous social media users have manifested a strong desire for recovery by creating positive content tagged with #Parisisaboutlife, #monmeilleursouvenirduBataclan (my best memory of Bataclan), or even the motto of Paris, #Fluctuatnecmergitur (Tossed but not sunk).

These elements may provide us insights on how we can read and transcribe virtual memories attached to a place, that is, the narrative of the place made by users to other users.

Urban imagery for traumascapes manifests in digital life

While the social media response in the wake of the Paris attacks is one of the most recent illustrations of the digitalization of traumascapes, there is no shortage of traumatized city spaces with which to explore the intersection of urban imagery and digital media. An analysis of cities with traumatic histories pre-dating the rise of the digital age can provide a rich source of data concerning the ongoing relationship between a population and their urbanity, as represented in the digital sphere. Sarajevo, capital city of the formerly war-torn nation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is a prime example of this phenomenon.

Social networks as a research tool in Sarajevo

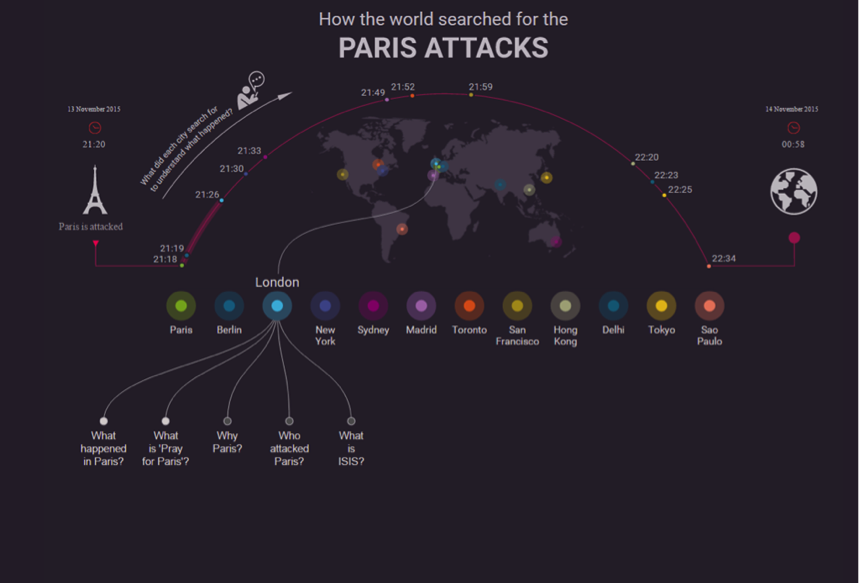

During my research on traumascapes in Sarajevo, In particular, I found photography to be a crucial research tool, rendering visible the key sites that characterise the Sarajevo traumascape, such as the abandoned bobsled track and other ruined structures on Mount Trebević, southeast of the city of Sarajevo. Social networks such as Instagram, a popular online mobile-photo sharing network, provided a ready-made pool of data of direct access to the reactions to a traumascape of a particular demographic in place and time. I used Instagram’s search tool to identify the hashtags and geolocalisations “Trebevic” and “bobstaza” (bobsleigh track in Bosnian) used between 2012 and 2014 in order to find relevant photographs, then classified these into themes . For this article, I updated this research by repeating the process with pictures from mid 2015 to early 2016.

To put the place into context, Yugoslavia became the first Communist country to host the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo in 1984, after which the bobsleigh and luge track remained in use by the city. Its site, Trebević, was a popular outdoor recreational area until the Siege of Sarajev. However, from the declaration of independence of Bosnia-Herzegovina from Yugoslavia in 1992, the site took on a different meaning. Trebević was transformed from a recreational area with positive associations from the Olympics to an artillery position for the Bosnian Serb Forces from which the city was regularly shelled until the conclusion of the war in December 1995 in order to weaken its citizens.

Almost twenty years later, due to political and economic challenges, the structures in Trebević have remained in ruin, at the border set in Dayton between the two parts of Sarajevo, the western part belonging to the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and eastern part to the Republika Srpska. The absence of cooperation between the two entities has led to an absence of action on the site. Neglected since the conclusion of the war, Trebević still seems to carry the trauma of the conflict. However, despite this apparent apathy, this has become a free space that is being organically used in many different ways, from war tourism to mountain biking, from graffiti making to drug dealing. This transition is reflected in people’s interpretations of the space through their expressions on social media.

Results

A significant insight into younger generations’ distinctive attitudes to the place was yielded through Instagram, the social media channel I decided to focus on. My analysis of the general trends related to “Trebevic” and “Bobstaza” revealed that the majority of the users were Bosnian. Between 2012 and 2014, people’s interpretations of this space often focused on the trauma enacted here. Many referred to the dates of the Olympics and the Siege, #landmines, #Sochi 2014, and #abandonedplaces. Yet, these hashtags were generally accompanied by others with positive connotations: #summer’, #feelinggreat, #family’, #friends, #chilling. (Fig 3) Pictures equally show the natural resources of the mountain and the bobsled track. By 2016, however, the latest posts referring to #Trebevic were mostly showing touristic views, while the tags referring to the bobsled track ("bobstaza") are much more associated with graffiti or the memory of the Winter Olympics than the war.

This research shed light on the novel engagement of young locals to the site: at once as a potential for fashionable, stylistic images and leisure, and concurrently as a landmark of their collective history, apprehended through the lens of time. Their light-hearted treatment of the past highlights the softening of traumatic memory. Hence it would be wrong to assert that this fallen džennet (paradise) has fully lost its function of “lungs of the city”, contrarily to what has been depicted in western media.

In a context where cities are both nodes of intense social media activity and potential targets of human and natural catastrophes, the question is therefore: how can we extract meaningful information by observing more carefully these vibrant data streams? With the virtual space becoming particularly active when a location-specific incident occurs, is it possible to leverage social media input to become more sensitive and conscious about existing or potential traumascapes in our cities?

Coordination and solidarity

Digital technology has already proved useful both during and in the aftermath of a crisis in understanding and responding to urges and needs, or in reflecting on ways of remembering spaces as complex as traumascapes. Social media networks can facilitate coordination as well as expression of solidarity in response to a crisis, as shown by the hashtag #PorteOuverte (Open Door) in Paris used by residents offering refuge during the lockdown induced by the terror attacks of 13th November, 2015. Another example is the controversial "safety check" tool, which transformed Facebook into a crisis information network for people willing to reassure their contacts of their safety.

A collective space for emotional expression and support

In addition to facilitating the practicalities of coping with an event during a crisis and its direct aftermath, social media offers a platform to project emotions and manifest a form of engagement onto a virtual space. Indeed, we can observe that intense collective and individual emotions both produce and impact space. They occur simultaneously in the physical and virtual public space, as shown by the production of spontaneous on-site memorials and the spread of hashtags. This happens in a context where city dwellers have increasingly engaged with urban space by liking, sharing or commenting on a geolocalisation or picture of a place. By doing so, individuals can enrich the virtual space with their emotional data, by associating emotions to local coordinates. Tagging oneself or one’s emotions on a virtual place is a 2.0 version of graffiti tagging a material space: such practices can be infinitely replicated without leaving direct physical traces, allowing people geographically far to occupy and engage with the site.

Enriching perceptions of the city

Interestingly enough, the city itself often appears to be perceived as the victim and the subject of resilience after a crisis. Following the Paris attacks, numerous social media users have manifested a strong desire for recovery by creating positive content tagged with #Parisisaboutlife, #monmeilleursouvenirduBataclan (my best memory of Bataclan), or even the motto of Paris, #Fluctuatnecmergitur (Tossed but not sunk).

These elements may provide us insights on how we can read and transcribe virtual memories attached to a place, that is, the narrative of the place made by users to other users.

Urban imagery for traumascapes manifests in digital life

While the social media response in the wake of the Paris attacks is one of the most recent illustrations of the digitalization of traumascapes, there is no shortage of traumatized city spaces with which to explore the intersection of urban imagery and digital media. An analysis of cities with traumatic histories pre-dating the rise of the digital age can provide a rich source of data concerning the ongoing relationship between a population and their urbanity, as represented in the digital sphere. Sarajevo, capital city of the formerly war-torn nation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is a prime example of this phenomenon.

Social networks as a research tool in Sarajevo

During my research on traumascapes in Sarajevo, In particular, I found photography to be a crucial research tool, rendering visible the key sites that characterise the Sarajevo traumascape, such as the abandoned bobsled track and other ruined structures on Mount Trebević, southeast of the city of Sarajevo. Social networks such as Instagram, a popular online mobile-photo sharing network, provided a ready-made pool of data of direct access to the reactions to a traumascape of a particular demographic in place and time. I used Instagram’s search tool to identify the hashtags and geolocalisations “Trebevic” and “bobstaza” (bobsleigh track in Bosnian) used between 2012 and 2014 in order to find relevant photographs, then classified these into themes . For this article, I updated this research by repeating the process with pictures from mid 2015 to early 2016.

To put the place into context, Yugoslavia became the first Communist country to host the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo in 1984, after which the bobsleigh and luge track remained in use by the city. Its site, Trebević, was a popular outdoor recreational area until the Siege of Sarajev. However, from the declaration of independence of Bosnia-Herzegovina from Yugoslavia in 1992, the site took on a different meaning. Trebević was transformed from a recreational area with positive associations from the Olympics to an artillery position for the Bosnian Serb Forces from which the city was regularly shelled until the conclusion of the war in December 1995 in order to weaken its citizens.

Almost twenty years later, due to political and economic challenges, the structures in Trebević have remained in ruin, at the border set in Dayton between the two parts of Sarajevo, the western part belonging to the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and eastern part to the Republika Srpska. The absence of cooperation between the two entities has led to an absence of action on the site. Neglected since the conclusion of the war, Trebević still seems to carry the trauma of the conflict. However, despite this apparent apathy, this has become a free space that is being organically used in many different ways, from war tourism to mountain biking, from graffiti making to drug dealing. This transition is reflected in people’s interpretations of the space through their expressions on social media.

Results

A significant insight into younger generations’ distinctive attitudes to the place was yielded through Instagram, the social media channel I decided to focus on. My analysis of the general trends related to “Trebevic” and “Bobstaza” revealed that the majority of the users were Bosnian. Between 2012 and 2014, people’s interpretations of this space often focused on the trauma enacted here. Many referred to the dates of the Olympics and the Siege, #landmines, #Sochi 2014, and #abandonedplaces. Yet, these hashtags were generally accompanied by others with positive connotations: #summer’, #feelinggreat, #family’, #friends, #chilling. (Fig 3) Pictures equally show the natural resources of the mountain and the bobsled track. By 2016, however, the latest posts referring to #Trebevic were mostly showing touristic views, while the tags referring to the bobsled track ("bobstaza") are much more associated with graffiti or the memory of the Winter Olympics than the war.

This research shed light on the novel engagement of young locals to the site: at once as a potential for fashionable, stylistic images and leisure, and concurrently as a landmark of their collective history, apprehended through the lens of time. Their light-hearted treatment of the past highlights the softening of traumatic memory. Hence it would be wrong to assert that this fallen džennet (paradise) has fully lost its function of “lungs of the city”, contrarily to what has been depicted in western media.

Compellingly, this implies the existence of multiple perceptions of urban environments and sets the stage for both conflict and mutual influence. This demographic stands at the very confluence of two very different dynamics: that of a local generation looking to find ways to move on from effects of war, and western fascination for the "eerie" and "authentic" modern ruins expressed for instance here or here. Social media tools show us how such associations can organically evolve and loosen over time to make way for different interpretations (Fig 4).

Fig 4 Photographic representations of the site on social media

|

@belmabelmabelma

Some people have added humorous comments to the sniper holes in the bobsleigh track such as ‘Open your mind/spirit’ and ‘peep show’. Following the precepts of surrealism, (s)he associated two different images in order to elicit surprise. Not only does disruption in people’s ways of thinking about these holes aim to liberate imagination, but it also creates a distance from the past, allows the mind to liberate itself from the tragedy. |

@hahahaharis

Taking into account the historical background as a fuel for the imaginative engagement with the place, it represents an opportunity at a time where abandoned and spectacular spaces are highly valued. In this vein, a popular picture on Instagram showed a sad Vucko (the Olympic mascot) sitting on the track illustrates this sad and humorous engagement with the past. |

|

@st_ylo

This picture shows a warning sign for potential mine danger, recalling the (false) idea that Mount Trebevic is a dangerous place due to the remains of war as one of the reasons locals tend to avoid the place. |

@utamiphotography

The more one is detached from the history of the place, the more (s)he can use the place without inhibition. |

Conclusion: the potential of understanding traumascapes

Through the data stream we produce by projecting our representations onto the virtual space, we may tell our own narratives of a place, we may reclaim our space, we may find a way to engage and make sense of traumatic events. In this is sense, beyond academic interests, there is a significant potential of developing visualization tools and apps akin to Instagram or foursquare as new forms of community engagement tools, even though currently limited to a community of regular users.

Such tools could help city governments or researchers identify hotspots in the urban landscape by analyzing the emotional data that is densifying the substance of public spaces by extending them into a new dimension, both temporal and spatial, in the virtual realm. These multiple layers of a same space may help them understand what intervention is preferable in a contentious space – as often the case with traumascapes. As shown by traumas associated with a certain place, for instance in Paris, New York, and Sarajevo, analyzing online users’ practices of memorialization on social media can provide us clues about the changing representations of traumascapes, and consequently, the complex dynamics of memory and recovery in our urban environments.

Through the data stream we produce by projecting our representations onto the virtual space, we may tell our own narratives of a place, we may reclaim our space, we may find a way to engage and make sense of traumatic events. In this is sense, beyond academic interests, there is a significant potential of developing visualization tools and apps akin to Instagram or foursquare as new forms of community engagement tools, even though currently limited to a community of regular users.

Such tools could help city governments or researchers identify hotspots in the urban landscape by analyzing the emotional data that is densifying the substance of public spaces by extending them into a new dimension, both temporal and spatial, in the virtual realm. These multiple layers of a same space may help them understand what intervention is preferable in a contentious space – as often the case with traumascapes. As shown by traumas associated with a certain place, for instance in Paris, New York, and Sarajevo, analyzing online users’ practices of memorialization on social media can provide us clues about the changing representations of traumascapes, and consequently, the complex dynamics of memory and recovery in our urban environments.

About the Author

|

Sophie Gleizes has worked in the fields of urban food policy and urban geography in France and Russia. A graduate in Humanities and Social Anthropology (Paris), she also holds a Masters degree in Nature, Society and Environmental Policy from the University of Oxford, focused on urban traumascapes. She currently works as a trainee at the European Commission (Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety). At UD/MH she focuses on how urban planners, designers and policymakers can engage with places associated with a community’s traumatic experiences, and how to work with the complexities of memory, identity, and resilience to enrich the experiences of people's urban environment. Contact her @SonechkaGleizes

|