|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2016;1:9

|

Improving the lives of people with dementia through urban design

Barbara Pani

Bartlett School of Planning, UK

Bartlett School of Planning, UK

Introduction

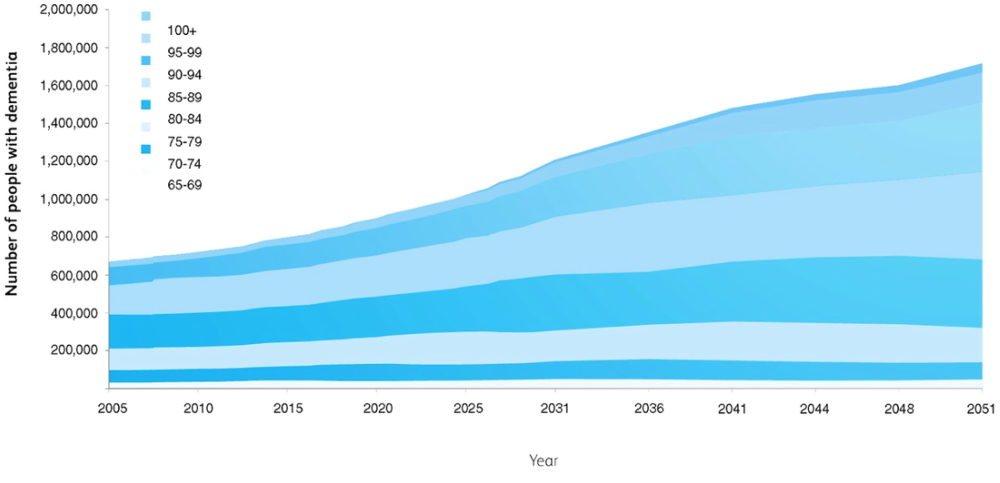

The rising prevalence of people living with dementia in our aging societies is one of the most striking demographic changes facing cities today (Fig 1) (Hungarian Presidency of the Council of the European Union, 2011, Bricocoli, 2012). With 24.3 million people worldwide currently diagnosed with dementia (Brorsson et al., 2011), aging societies will be affected by a decline of the supporting working population, highlighting the need for solutions to improve the wellbeing of dementia sufferers within the healthcare services and the living environment (Bricocoli and Marchigiani, 2012). In the UK there are 800,000 people living with dementia, one third of whom live alone at home. Projections show that in 2051 in the UK alone there are expected to be 170,0000 dementia sufferers (Alzheimer society, 2013), setting dementia as a public health priority. This creates an imperative to better understand the relationship between mental health and the built environment, their mutual dependence at the urban scale, and the correlation between social and spatial aspects of mental health in cities, to help us design better environments for people with dementia.

The rising prevalence of people living with dementia in our aging societies is one of the most striking demographic changes facing cities today (Fig 1) (Hungarian Presidency of the Council of the European Union, 2011, Bricocoli, 2012). With 24.3 million people worldwide currently diagnosed with dementia (Brorsson et al., 2011), aging societies will be affected by a decline of the supporting working population, highlighting the need for solutions to improve the wellbeing of dementia sufferers within the healthcare services and the living environment (Bricocoli and Marchigiani, 2012). In the UK there are 800,000 people living with dementia, one third of whom live alone at home. Projections show that in 2051 in the UK alone there are expected to be 170,0000 dementia sufferers (Alzheimer society, 2013), setting dementia as a public health priority. This creates an imperative to better understand the relationship between mental health and the built environment, their mutual dependence at the urban scale, and the correlation between social and spatial aspects of mental health in cities, to help us design better environments for people with dementia.

Fig 1: Dementia prevalence trends in the UK by age, Alzheimer Society

While improvements to dementia-related healthcare have been studied as technical-led solutions that include the outdoor environment around specific institutions, little has been done within the city at the neighborhood scale to improve public space in the vicinity of those with dementia. One such analysis of a sample neighbourhood, based on research demonstrating the benefits of the walking experience for people with dementia, examines the 'walkable zone of experience' (Blackman, 2006), and proposes one method to tackle the issue. However, it is clear that a set of guidelines or investigative principles are needed to better understand how to approach this challenge.

Guidelines development: an answer within the urban design context

In order to develop investigative principles to understand the relationship betwee dementia and the neighbourhood environment, we combined a literature review by Mitchell and Burton with key lessons from four case studies. Our research aimed to understand how to develop inclusive neighbourhoods within the city that simultaneously meet the needs of people with dementia, and the general population. Mitchell and Burton’s work, 'Inclusive urban design, streets for life', proposed six key design principles for outdoor space to achieve this:

- familiar

- accessible

- legible

- distinctive

- safe

- comfortable

In order to further understand how to respond to the challenges of designing a city neighbourhood inclusive of people with dementia, intergenerational communities, and the challenges of aging in place, other useful lessons can be learned by the observation of different approaches currently being implemented.

Case Studies

|

Case 1: A gated community for people with dementia - Weesp, Netherlands

In the Netherlands, a nursing care home has been designed in the form a neighbourhood that the residents are encouraged to safely explore. This aims to create a familiar environment with neighbourhood-style facilities such as a theatre, a restaurant-cafe, a supermarket, a park and a boulevard, that allow residents to enjoy recognisable daily activities and a familiar sense of place, run by carers. According to Rupprecht (2012) ‘De Hogewayk’ has had a positive impact on the level of medication its residents require compared to those living in another old care facility in Weesp. |

|

Case 2: Bruges - a dementia-friendly city, Belgium

Bruges is the first so-called ‘dementia-friendly city’. In Bruges the starting point for developing a long term approach through the creation of dementia friendly communities has focused on recognizing the rights of people with dementia as citizens in order to give them the opportunity to access facilities with which they are familiar (Crampton and Eley, 2013). |

|

Case 3: Intergenerational housing in Alicante, Spain

The aim of the intergenerational building in Alicante, Spain is to enhance the quality of life of older people who, partly due to their housing, can face social challenges such as isolation, loneliness and vulnerability. The project considers older people to be active agents living independently rather than passive recipients of services (Municipal project for intergenerational housing and community services in Alicante, 2012). The integration between old and young people is realized through selecting young people with characteristics including motivation, empathy and suitability to work in social programs. Each young individual is linked to four older people and spends at least four hours per week in community service, supporting cultural and recreational activities for the residents (Garcia and Marti 2014). |

|

Case 4: Community health services in Trieste, Italy

Habitat-Microareas program highlights the importance of the reorganization of healthcare services at the community level as an alternative to hospitalization (Bricocoli and Marchigiani 2012). It is a joint initiative by the Public Health Agency (ASS1) and the Social Housing Agency (ATER). Today the program covers fourteen micro-areas characterized by the presence of public housing settlements that show high levels of health and social problems (Bifulco and Bricocoli, 2010). The neighborhood is used as a place in which these changes can be tested and implemented throughout the redesign of the open space and the reorganization of the healthcare services (Bricocoli and Marchigiani, 2012). The outcomes of this program can be observed in the activation of social services within dwellings on the estate. |

Development of the Principles

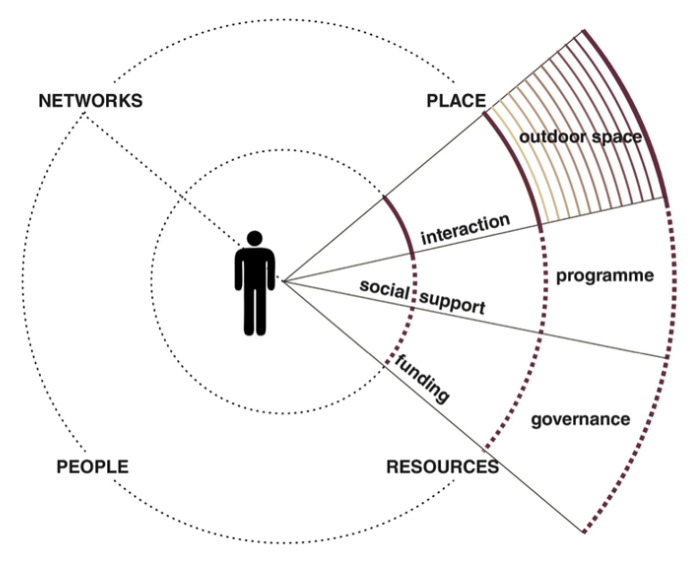

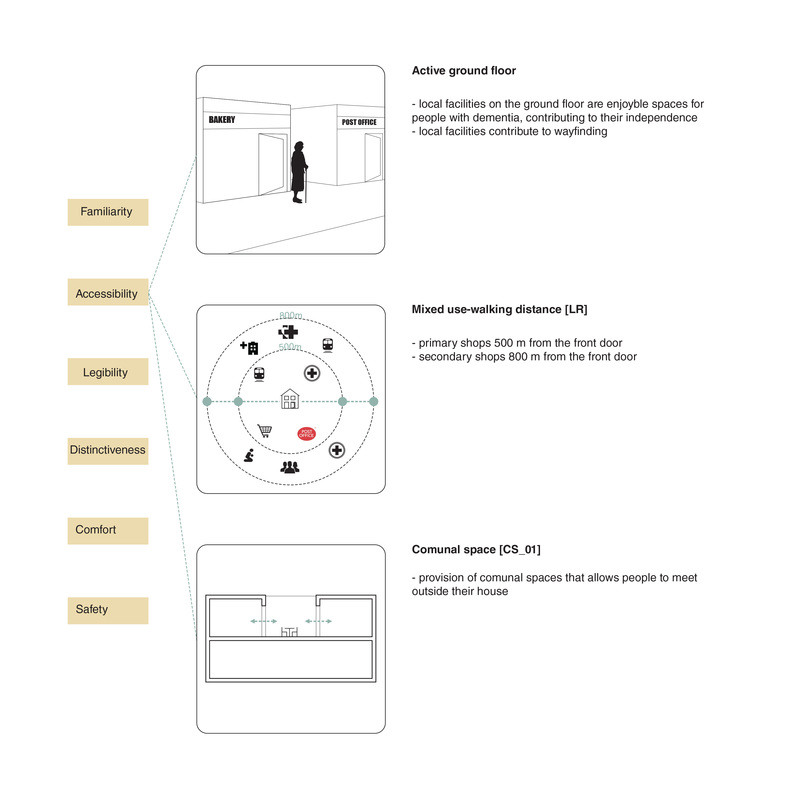

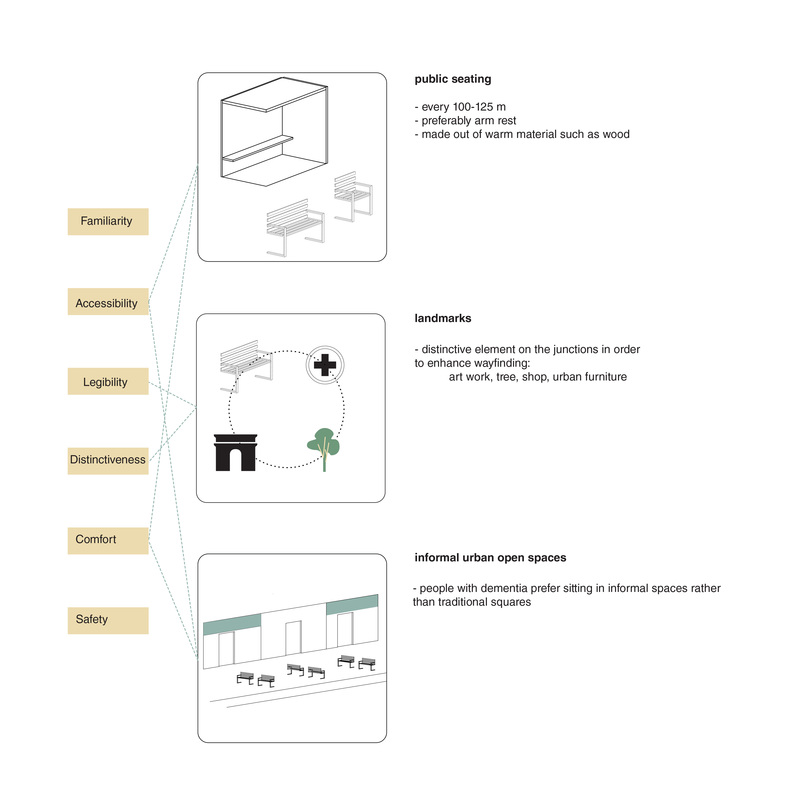

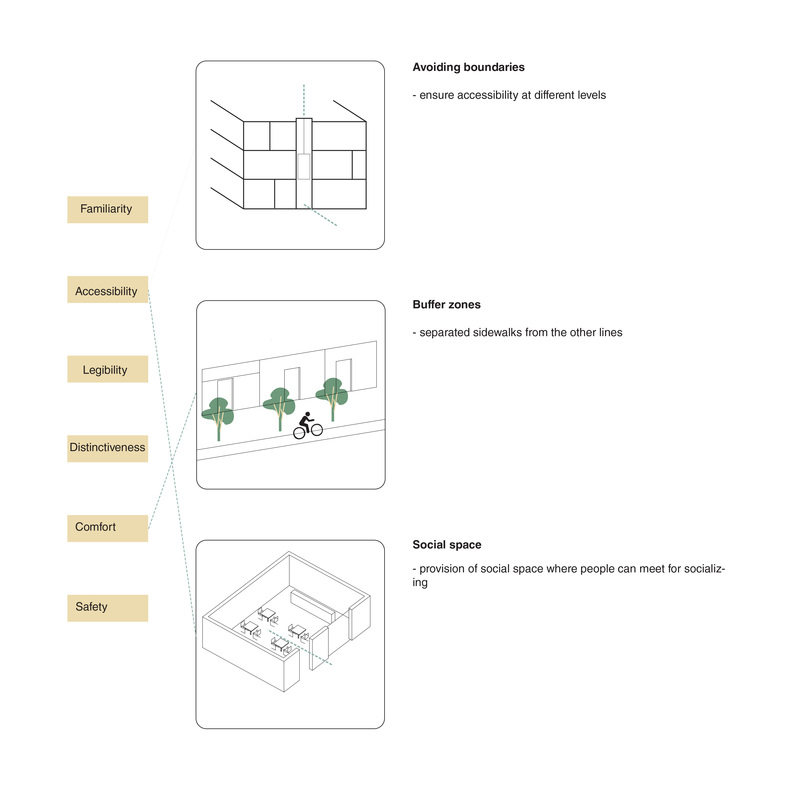

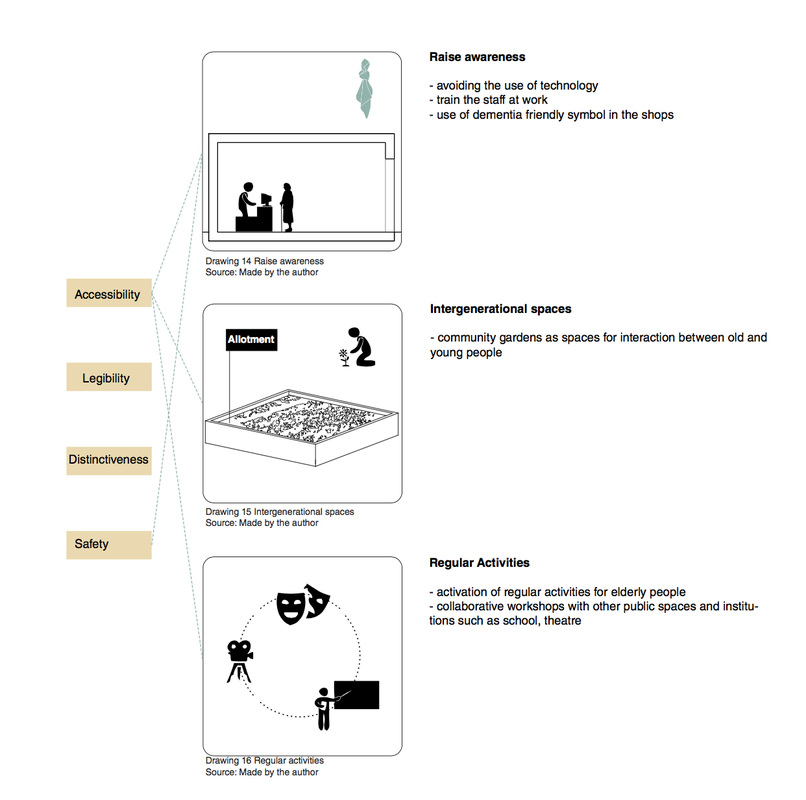

Analysis of these different models resulted in the development of a set of principles for designing outdoor neighbourhoods that, while catering to the general public, meet the specific needs of people who have dementia (Fig 2).

Fig 2: Principles for dementia-friendly outdoor neighbourhoods

Analysis of these different models resulted in the development of a set of principles for designing outdoor neighbourhoods that, while catering to the general public, meet the specific needs of people who have dementia (Fig 2).

Fig 2: Principles for dementia-friendly outdoor neighbourhoods

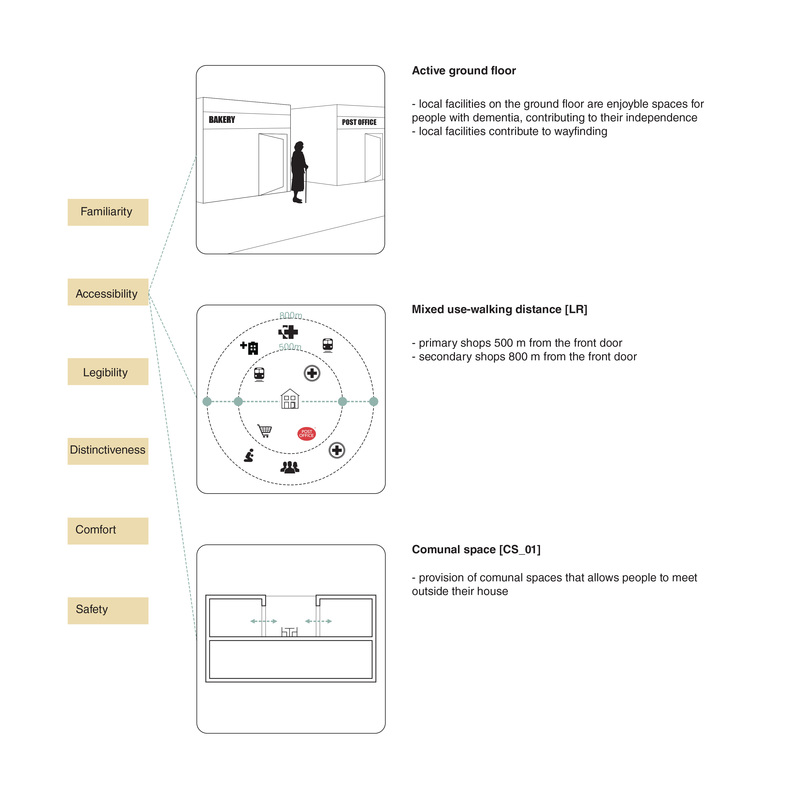

Fig 3: Specific recommendations for dementia-friendly outdoor neighbourhoods that emerged from analysis of the research and case studies

Conclusion

This research highlights the importance of improvements at a neighborhood scale as an opportunity to enhance independent lives for people affected by dementia, particularly at its early stages. The developed design principles, based on the consideration of the literature review and the identified case studies could be used to guide good practice of urban design. Age-friendly initiatives do not necessarily have to marginalize any category of population; on the contrary they should consider the needs of everybody (Fitzgerald and Caro, 2014) and contribute to inclusive design practice. From this study two important reflections emerge:

First, there is a discourse in cities like London about retrofitting existing buildings instead of massive redevelopment of estates. Research shows that people with dementia tend to be less disoriented when they can recognize a familiar environment. Hence, it could be argued that refurbishing old estates contributes to the enhancement of social sustainability at the urban level.

Secondly, it could be said that the approach of de-institutionalization could be applied, where appropriate, to other mental illnesses, enhancing independence of both people with mental illnesses and their carers. Public authorities and the public healthcare sector should consider physical improvements to neighborhoods as public health priorities. It is important in these discussions to underline the problem of marginalization and stigma. Working to improve mental health should include avoiding segregation, and a focus on promoting capabilities in the context of positive, productive community dynamics.

Thirdly, the importance of developing social spaces at the neighborhood scale. The role of public space for meeting and socialising has a wide range of benefits for the whole community, including for those with dementia. While current demographic changes have highlighted dementia as a recognized public health priority, treatment for other mental illnesses through informed urban design should also be considered for inclusion in public health policy.

References

Bricocoli M., Marchigiani E. (2011) Cities and Demographic Change: space reconsidered and the future of social housing estates in Trieste. Enhr Conference 2011 – 58 July, Toulouse

Bricocoli M., Marchigiani E. (2012), Growing old in cities. Council housing estates in Trieste as laboratories for new perspectives in urban planning. European spatial research and policy.

Blackman T. et al. (2003), The Accessibility of Public Spaces for People with Dementia: A new priority for the 'open city'. Disability & society, 18, 3 pp. 357371

Blackman T. (2006), Placing health: neighbourhood renewal, health improvement and complexity. The Policy press, Bristol

Brorsson A. et al. (2011), Accessibility in public spaces as perceived by people with Alzheimer's disease. Dementia, 10(4), 587602

Mitchell L., Burton E., Raman Shibu (2007) Dementia friendly cities: designing intelligible neighborhoods for life, Journal of Urban design 9:1, pp. 89101

Mitchell L., Burton E. (2010), Designing Dementia Friendly neighborhoods: Helping people with dementia to get out and about Environment, Design and Rehabilitation (EDR) Series.

Sen A. (2010), The Idea of Justice. London, Penguin Books.

Bricocoli M., Marchigiani E. (2011) Cities and Demographic Change: space reconsidered and the future of social housing estates in Trieste. Enhr Conference 2011 – 58 July, Toulouse

Bricocoli M., Marchigiani E. (2012), Growing old in cities. Council housing estates in Trieste as laboratories for new perspectives in urban planning. European spatial research and policy.

Blackman T. et al. (2003), The Accessibility of Public Spaces for People with Dementia: A new priority for the 'open city'. Disability & society, 18, 3 pp. 357371

Blackman T. (2006), Placing health: neighbourhood renewal, health improvement and complexity. The Policy press, Bristol

Brorsson A. et al. (2011), Accessibility in public spaces as perceived by people with Alzheimer's disease. Dementia, 10(4), 587602

Mitchell L., Burton E., Raman Shibu (2007) Dementia friendly cities: designing intelligible neighborhoods for life, Journal of Urban design 9:1, pp. 89101

Mitchell L., Burton E. (2010), Designing Dementia Friendly neighborhoods: Helping people with dementia to get out and about Environment, Design and Rehabilitation (EDR) Series.

Sen A. (2010), The Idea of Justice. London, Penguin Books.