|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2016;1:7

|

Might beautiful places have a quantifiable impact on our wellbeing?

Chanuki Illushka Seresinhe

University of Warwick

University of Warwick

In our everyday lives we are exposed to a wide range of outdoor settings. Intuitively, it seems that some settings, such as a beautiful view of a calm lake, help us feel more relaxed. While others, such as a cluster of dilapidated graffiti-ridden buildings, seem to make us feel distressed or even afraid. What if the beauty of the outdoors actually has a quantifiable effect on our wellbeing? What might this mean as to how we design our future urban spaces?

Philosophers, policy-makers and urban planners have puzzled over this question for years, but have been held back by the lack of data on the beauty of our environment. Thus, to date, this discussion has been mainly centred on aspects we can measure, such as the amount of greenspace or the presence of trees (Bratman, Daily, Levy, Gross, 2015; Bratman, Hamilton, Hahn, Daily, Gross, 2015; Mackerron & Mourato, 2013; Thompson et al., 2012; Van den Berg, Maas, Verheij & Groenewegen, 2010; White, Alcock, Wheeler & Depledge, 2013).

The ubiquitous presence of the Internet in today’s society has begun to change this. Data generated through our increasing online interactions are helping scientists gain a range of new insights into human behaviour in the real world (Bollen, Mao & Zeng, 2011; Botta, Moat & Preis, 2015; Choi & Varian, 2012; King, 2011; Lazer et al., 2009; Moat et al., 2013; Moat, Preis, Olivola, Liu & Chater, 2014; Preis, Moat, Bishop, Treleaven & Stanley, 2013; Preis, Moat & Stanley, 2013; Preis, Moat, Stanley, & Bishop, 2012; Vespignani, 2009; Yasseri, Sumi, Rung, Kornai & Kertész, 2012).

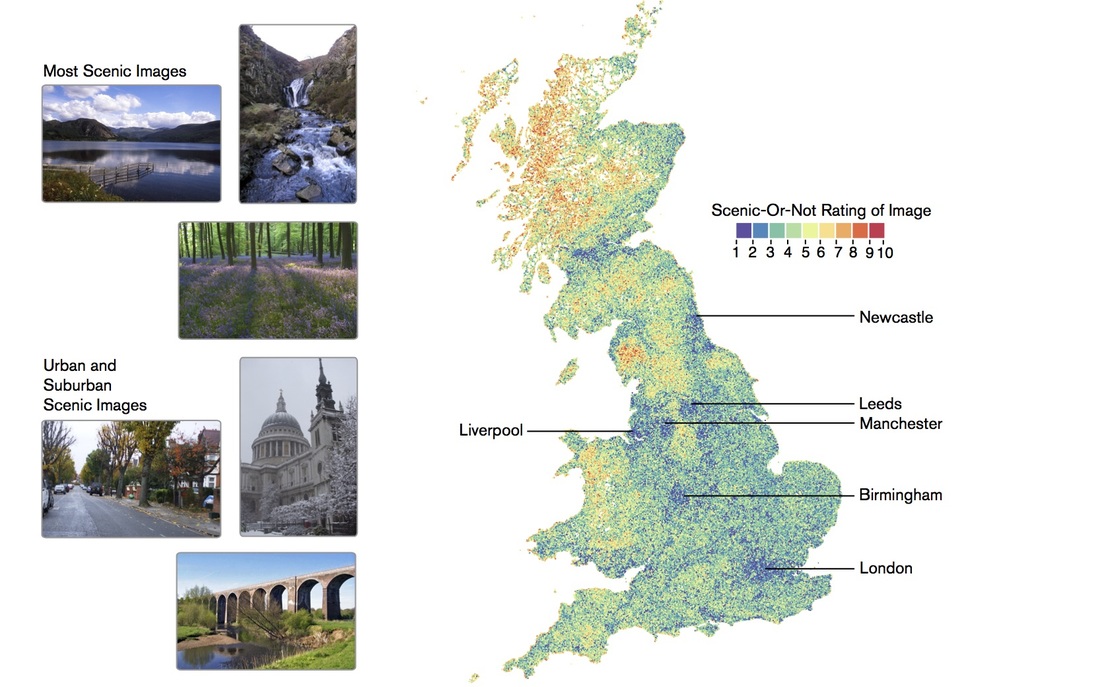

In our quest to understand how the beauty of the environment impacts human wellbeing, we called upon crowdsourced data from the website Scenic-Or-Not. This simple website, originally created by mySociety, asks people to rate the 'scenicness' of random images of the environment sourced from Geograph covering nearly 95% of the 1 km grid squares of Great Britain. To date we have over 1.5 million crowdsourced ratings informing us of the subjective beauty of Great Britain.

Combining this geographic scenic data with census data on people's reports of their own health has led to a remarkable finding: across the entire English dataset, we find that inhabitants of more scenic environments report better health (Seresinhe, Preis & Moat, 2015). Unquestionably, certain neighborhoods may be wealthier, have better access to services or have less air pollution; however these results hold, even after taking such crucial factors into consideration.

The definition of 'scenicness' may vary depending on the environmental context. Scenicness in the countryside is inevitably not the same as scenicness in a bustling cityscape. As we have the ability to hone the aesthetics of the environments we build, we wanted to further understand how scenicness might impact people's wellbeing in urban and suburban environments. We found that people do indeed feel healthier even in more scenic urban and suburban environments, which implies that how we choose to design built-up areas could have a crucial impact on our wellbeing.

Our investigations continue and we have recently been given the opportunity to analyse data from the innovative iPhone app Mappiness, created by Dr George MacKerron and Dr Susana Mourato at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). Mappiness polls users daily about their level of happiness, current activities and basic details about their surroundings. Exploiting these happiness ratings, MacKerron and Mourato (2013) found that people are substantially happier in green and natural environments than in urban ones.

We are exploring data from Mappiness to investigate whether people are happier and more relaxed in settings that are more scenic. While many of us would agree that spending time in outstanding natural beauty results in a feeling of general contentedness, it is difficult to intuit whether spending time in more picturesque built-up areas has a similar effect. Online data is offering us a novel opportunity to investigate this crucial question. Follow us @thoughtsymmetry and @thedatascilab for further developments on this research.

Big online datasets are helping us to quantify the link between environmental aesthetics and human wellbeing. The beauty of our everyday environment might have more practical importance than previously believed.

Philosophers, policy-makers and urban planners have puzzled over this question for years, but have been held back by the lack of data on the beauty of our environment. Thus, to date, this discussion has been mainly centred on aspects we can measure, such as the amount of greenspace or the presence of trees (Bratman, Daily, Levy, Gross, 2015; Bratman, Hamilton, Hahn, Daily, Gross, 2015; Mackerron & Mourato, 2013; Thompson et al., 2012; Van den Berg, Maas, Verheij & Groenewegen, 2010; White, Alcock, Wheeler & Depledge, 2013).

The ubiquitous presence of the Internet in today’s society has begun to change this. Data generated through our increasing online interactions are helping scientists gain a range of new insights into human behaviour in the real world (Bollen, Mao & Zeng, 2011; Botta, Moat & Preis, 2015; Choi & Varian, 2012; King, 2011; Lazer et al., 2009; Moat et al., 2013; Moat, Preis, Olivola, Liu & Chater, 2014; Preis, Moat, Bishop, Treleaven & Stanley, 2013; Preis, Moat & Stanley, 2013; Preis, Moat, Stanley, & Bishop, 2012; Vespignani, 2009; Yasseri, Sumi, Rung, Kornai & Kertész, 2012).

In our quest to understand how the beauty of the environment impacts human wellbeing, we called upon crowdsourced data from the website Scenic-Or-Not. This simple website, originally created by mySociety, asks people to rate the 'scenicness' of random images of the environment sourced from Geograph covering nearly 95% of the 1 km grid squares of Great Britain. To date we have over 1.5 million crowdsourced ratings informing us of the subjective beauty of Great Britain.

Combining this geographic scenic data with census data on people's reports of their own health has led to a remarkable finding: across the entire English dataset, we find that inhabitants of more scenic environments report better health (Seresinhe, Preis & Moat, 2015). Unquestionably, certain neighborhoods may be wealthier, have better access to services or have less air pollution; however these results hold, even after taking such crucial factors into consideration.

The definition of 'scenicness' may vary depending on the environmental context. Scenicness in the countryside is inevitably not the same as scenicness in a bustling cityscape. As we have the ability to hone the aesthetics of the environments we build, we wanted to further understand how scenicness might impact people's wellbeing in urban and suburban environments. We found that people do indeed feel healthier even in more scenic urban and suburban environments, which implies that how we choose to design built-up areas could have a crucial impact on our wellbeing.

Our investigations continue and we have recently been given the opportunity to analyse data from the innovative iPhone app Mappiness, created by Dr George MacKerron and Dr Susana Mourato at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). Mappiness polls users daily about their level of happiness, current activities and basic details about their surroundings. Exploiting these happiness ratings, MacKerron and Mourato (2013) found that people are substantially happier in green and natural environments than in urban ones.

We are exploring data from Mappiness to investigate whether people are happier and more relaxed in settings that are more scenic. While many of us would agree that spending time in outstanding natural beauty results in a feeling of general contentedness, it is difficult to intuit whether spending time in more picturesque built-up areas has a similar effect. Online data is offering us a novel opportunity to investigate this crucial question. Follow us @thoughtsymmetry and @thedatascilab for further developments on this research.

Big online datasets are helping us to quantify the link between environmental aesthetics and human wellbeing. The beauty of our everyday environment might have more practical importance than previously believed.

Fig 1

The Scenic-Or-Not websites gives us the novel opportunity to measure 'scenicness' all around Great Britain. We have over 1.5 millions votes rating the scenic quality of images covering nearly 95% of the 1 km grid squares of Great Britain. Each point on the map represents one image. While the highest rated scenic images tend to be dominated by stunning natural scenery including mountains, forests and waterfalls, in urban and suburban areas, the definition of scenicness is quite varied. People not only rate natural images as scenic, but also beautiful buildings, leafy residential streets and bridges.

Photographers of scenic images from top to bottom: Mick Borroff, Tom Richardson, Andrew Smith, John Lord, Phillip Perry, Bob Abell. Copyright of the images is retained by the photographers. Images are licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic License.

The Scenic-Or-Not websites gives us the novel opportunity to measure 'scenicness' all around Great Britain. We have over 1.5 millions votes rating the scenic quality of images covering nearly 95% of the 1 km grid squares of Great Britain. Each point on the map represents one image. While the highest rated scenic images tend to be dominated by stunning natural scenery including mountains, forests and waterfalls, in urban and suburban areas, the definition of scenicness is quite varied. People not only rate natural images as scenic, but also beautiful buildings, leafy residential streets and bridges.

Photographers of scenic images from top to bottom: Mick Borroff, Tom Richardson, Andrew Smith, John Lord, Phillip Perry, Bob Abell. Copyright of the images is retained by the photographers. Images are licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic License.

References

Bollen, J., Mao, H., & Zeng, X. (2011). Twitter mood predicts the stock market. Journal of Computer Science, 2(1), 1-8. doi:10.1016/j.jocs.2010.12.007

Botta, F., Moat, H. S., & Preis, T. (2015). Quantifying crowd size with mobile phone and Twitter data. Royal Society Open Science, 2(5), 150162. doi:10.1098/rsos.150162

Bratman, G. N., Daily, G. C., Levy, B. J., & Gross, J. J. (2015). The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landscape and Urban Planning, 138, 41-50.

Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., Hahn, K. S., Daily, G. C., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(28), 8567-8572. doi:10.1073/pnas.1510459112

Choi, H., & Varian, H. (2012). Predicting the Present with Google Trends. Economic Record, 88(s1), 2-9. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4932.2012.00809.x

King, G. (2011). Ensuring the Data-Rich Future of the Social Sciences. Science, 331(6018), 719-721. doi:10.1126/science.1197872

Lazer, D., Pentland, A., Adamic, L., Aral, S., Barabási, A.-L., Brewer, D., . . . Van, A., Marshall. (2009). Computational Social Science. Science, 323(5915), 721-723. doi:10.1126/science.1167742

MacKerron, G., & Mourato, S. (2013). Happiness is greater in natural environments. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 992-1000. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.010

Moat, H. S., Curme, C., Avakian, A., Kenett, D. Y., Stanley, H. E., & Preis, T. (2013). Quantifying Wikipedia Usage Patterns Before Stock Market Moves. Scientific Reports, 3, 1801. doi:10.1038/srep01801

Moat, H. S., Preis, T., Olivola, C. Y., Liu, C., & Chater, N. (2014). Using big data to predict collective behavior in the real world. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 37(01), 92-93. doi:10.1017/S0140525X13001817

Preis, T., Moat, H. S., Bishop, S. R., Treleaven, P., & Stanley, H. E. (2013). Quantifying the Digital Traces of Hurricane Sandy on Flickr. Scientific Reports, 3, 3141. doi:10.1038/srep03141

Preis, T., Moat, H. S., & Stanley, H. E. (2013). Quantifying Trading Behavior in Financial Markets Using Google Trends. Scientific Reports, 3, 1684. doi:10.1038/srep01684

Preis, T., Moat, H. S., Stanley, H. E., & Bishop, S. R. (2012). Quantifying the Advantage of Looking Forward. Scientific Reports, 2, 350-350. doi:Article

Seresinhe, C. I., Preis, T., & Moat, H. S. (2015). Quantifying the Impact of Scenic Environments on Health. Scientific Reports, 16899. doi:10.1038/srep16899

Thompson, C. W., Roe, J., Aspinall, P., Mitchell, R., Clow, A., & Miller, D. (2012). More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landscape and Urban Planning, 105(3), 221-229. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.12.015

van den Berg, A. E., Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2010). Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Social Science and Medicine, 70(8), 1203-1210. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.002

Vespignani, A. (2009). Predicting the Behavior of Techno-Social Systems. Science, 325(5939), 425-428. doi:10.1126/science.1171990

White, M. P., Alcock, I., Wheeler, B. W., & Depledge, M. H. (2013). Would you be happier living in a greener urban area? A fixed-effects analysis of panel data. Psychological Science, 24(6), 920-928. doi:10.1177/0956797612464659

Yasseri, T., Sumi, R., Rung, A., Kornai, A., & Kertész, J. (2012). Dynamics of Conflicts in Wikipedia. PLoS ONE, 7(6), e38869-. doi:doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038869

Bollen, J., Mao, H., & Zeng, X. (2011). Twitter mood predicts the stock market. Journal of Computer Science, 2(1), 1-8. doi:10.1016/j.jocs.2010.12.007

Botta, F., Moat, H. S., & Preis, T. (2015). Quantifying crowd size with mobile phone and Twitter data. Royal Society Open Science, 2(5), 150162. doi:10.1098/rsos.150162

Bratman, G. N., Daily, G. C., Levy, B. J., & Gross, J. J. (2015). The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landscape and Urban Planning, 138, 41-50.

Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., Hahn, K. S., Daily, G. C., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(28), 8567-8572. doi:10.1073/pnas.1510459112

Choi, H., & Varian, H. (2012). Predicting the Present with Google Trends. Economic Record, 88(s1), 2-9. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4932.2012.00809.x

King, G. (2011). Ensuring the Data-Rich Future of the Social Sciences. Science, 331(6018), 719-721. doi:10.1126/science.1197872

Lazer, D., Pentland, A., Adamic, L., Aral, S., Barabási, A.-L., Brewer, D., . . . Van, A., Marshall. (2009). Computational Social Science. Science, 323(5915), 721-723. doi:10.1126/science.1167742

MacKerron, G., & Mourato, S. (2013). Happiness is greater in natural environments. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 992-1000. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.010

Moat, H. S., Curme, C., Avakian, A., Kenett, D. Y., Stanley, H. E., & Preis, T. (2013). Quantifying Wikipedia Usage Patterns Before Stock Market Moves. Scientific Reports, 3, 1801. doi:10.1038/srep01801

Moat, H. S., Preis, T., Olivola, C. Y., Liu, C., & Chater, N. (2014). Using big data to predict collective behavior in the real world. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 37(01), 92-93. doi:10.1017/S0140525X13001817

Preis, T., Moat, H. S., Bishop, S. R., Treleaven, P., & Stanley, H. E. (2013). Quantifying the Digital Traces of Hurricane Sandy on Flickr. Scientific Reports, 3, 3141. doi:10.1038/srep03141

Preis, T., Moat, H. S., & Stanley, H. E. (2013). Quantifying Trading Behavior in Financial Markets Using Google Trends. Scientific Reports, 3, 1684. doi:10.1038/srep01684

Preis, T., Moat, H. S., Stanley, H. E., & Bishop, S. R. (2012). Quantifying the Advantage of Looking Forward. Scientific Reports, 2, 350-350. doi:Article

Seresinhe, C. I., Preis, T., & Moat, H. S. (2015). Quantifying the Impact of Scenic Environments on Health. Scientific Reports, 16899. doi:10.1038/srep16899

Thompson, C. W., Roe, J., Aspinall, P., Mitchell, R., Clow, A., & Miller, D. (2012). More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landscape and Urban Planning, 105(3), 221-229. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.12.015

van den Berg, A. E., Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2010). Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Social Science and Medicine, 70(8), 1203-1210. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.002

Vespignani, A. (2009). Predicting the Behavior of Techno-Social Systems. Science, 325(5939), 425-428. doi:10.1126/science.1171990

White, M. P., Alcock, I., Wheeler, B. W., & Depledge, M. H. (2013). Would you be happier living in a greener urban area? A fixed-effects analysis of panel data. Psychological Science, 24(6), 920-928. doi:10.1177/0956797612464659

Yasseri, T., Sumi, R., Rung, A., Kornai, A., & Kertész, J. (2012). Dynamics of Conflicts in Wikipedia. PLoS ONE, 7(6), e38869-. doi:doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038869

About the Author

|

Chanuki Illushka Seresinhe is a Doctoral Researcher at the Warwick Business School, University of Warwick. Her research involves using online data from sources such as Flickr and Twitter combined with socioeconomic data to understand how the aesthetics of the environment impacts wellbeing. Her research has been featured in the press worldwide including the Telegraph, ArchDaily and the Guardian. Before returning to university, Chanuki had a diverse career that including running her own digital design consultancy for over 8 years. Contact her @thoughtsymmetry

|