Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2021:7;11

CITY CASE STUDY

Age-friendly urban design and mental health in Sydney, Australia: a city case study

Safiah Moore

Arup, Associate, Planning Leader, Indonesia

Georgia Vitale

Grimshaw, Practice Leader, Urban Strategy and Social Outcomes, Australia

Arup, Associate, Planning Leader, Indonesia

Georgia Vitale

Grimshaw, Practice Leader, Urban Strategy and Social Outcomes, Australia

Citation: Moore S, Vitale G (2021). Age-friendly urban design and mental health in Sydney, Australia: a case study. Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 7;11

The authors acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First People and traditional custodians of the land and waters of this place we now call Sydney. We pay our respect to Elders past, present and future.

Introduction

The purpose of this case study is to describe how metropolitan Sydney, the capital city of the State of New South Wales (NSW), addresses age-friendly urban design including designing cities for people with dementia. This case study follows the format and interview protocols established by the Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health to explore Sydney’s current policy imperatives for age friendly cities, the mental health of older adults and those with dementia. It is supplemented with the perspectives of urban and health professionals, in order to highlight priorities for Sydney and draw out lessons for other cities.

Creating age and dementia-friendly communities is a multi-dimensional task and there are many aspects that are beyond the role of urban designers and planners (PIA, 2018). There are however important aspects of urban design that can impact older persons as they experience changes in mental, physical and social functioning, particularly as across Australia it is estimated that overall, 95.3% of older people live in households and 70% of people with dementia are living at home in their community, rather than in residential aged care facilities (AIHW, 2013). Therefore, the degree of inclusivity and accessibility of the urban environment, both within the remit of planners and designers, is fundamental to supporting older adults and those with dementia as well as their carers.

The desire to remain in one's community corresponds with a study undertaken by the Committee for Sydney (2019) which found that 71% of survey respondents expect to remain living in their area in Sydney during retirement. There is clearly a strong need to design our neighbourhoods to support our ageing population and those with dementia. Greater emphasis on the local environment has also been amplified by the COVID-19 lockdowns in showing the value of proximity and the importance of the neighbourhood scale (Juvillà & Rofin, 2021).

Creating age and dementia-friendly communities is a multi-dimensional task and there are many aspects that are beyond the role of urban designers and planners (PIA, 2018). There are however important aspects of urban design that can impact older persons as they experience changes in mental, physical and social functioning, particularly as across Australia it is estimated that overall, 95.3% of older people live in households and 70% of people with dementia are living at home in their community, rather than in residential aged care facilities (AIHW, 2013). Therefore, the degree of inclusivity and accessibility of the urban environment, both within the remit of planners and designers, is fundamental to supporting older adults and those with dementia as well as their carers.

The desire to remain in one's community corresponds with a study undertaken by the Committee for Sydney (2019) which found that 71% of survey respondents expect to remain living in their area in Sydney during retirement. There is clearly a strong need to design our neighbourhoods to support our ageing population and those with dementia. Greater emphasis on the local environment has also been amplified by the COVID-19 lockdowns in showing the value of proximity and the importance of the neighbourhood scale (Juvillà & Rofin, 2021).

Methods

Scope

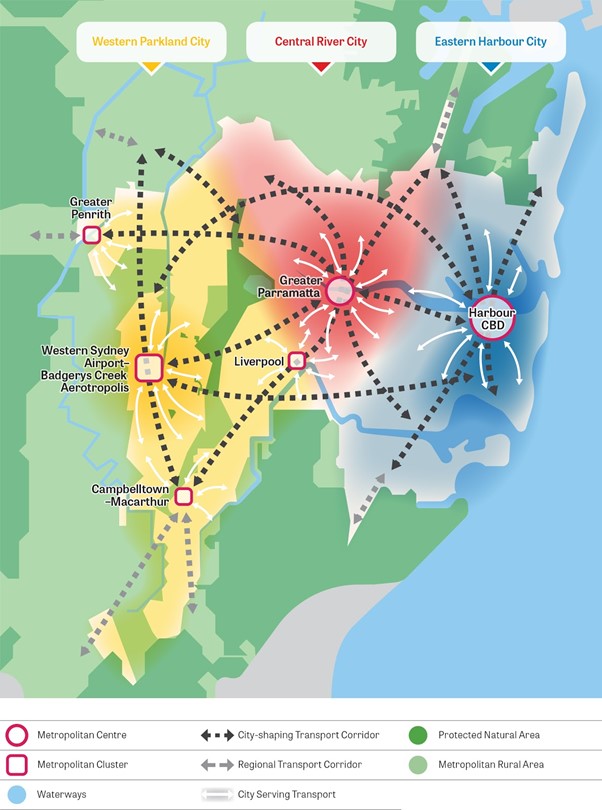

The scope of this case study is metropolitan Sydney comprising its 33 metropolitan councils. It makes reference to the Greater Sydney Commission’s metropolis of three cities: the Western City; the Central City; and the Eastern City.

The scope of this case study is metropolitan Sydney comprising its 33 metropolitan councils. It makes reference to the Greater Sydney Commission’s metropolis of three cities: the Western City; the Central City; and the Eastern City.

Figure 1: Metropolitan Sydney Structure Plan. Source: Greater Sydney Commission, 2018

Figure 2: George Street, Sydney. Source © Ashleigh Hughes

Literature search

A search was conducted in 2021 to identify age-friendly urban design policies, programmes and developments, with a specific focus on designing cities for people with dementia, and other mental health conditions from the perspective of older people. This information was analysed and assessed for relevance to Sydney. The literature review extends upon previous research undertaken by the authors in developing an age friendly cities index in 2015.

Interviews

Ten Sydney-based academics, public health specialists, urban and transport planners, architects and urban designers were identified using snowball sampling. Semi-structured interviews were conducted using the Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health interview protocol. Interviewees were asked about age-friendly urban design with a specific focus on designing cities for people with dementia, and other mental disorders. They were also asked to identify where there is an intent to prioritise ageing and the mental health of older persons in urban planning and design, any known guidelines and policies currently in place.

It is acknowledged that further depth of analysis could have been gathered from interviews with people living with dementia and their carers, however, due to the time limitations of this study were not able to be completed.

A search was conducted in 2021 to identify age-friendly urban design policies, programmes and developments, with a specific focus on designing cities for people with dementia, and other mental health conditions from the perspective of older people. This information was analysed and assessed for relevance to Sydney. The literature review extends upon previous research undertaken by the authors in developing an age friendly cities index in 2015.

Interviews

Ten Sydney-based academics, public health specialists, urban and transport planners, architects and urban designers were identified using snowball sampling. Semi-structured interviews were conducted using the Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health interview protocol. Interviewees were asked about age-friendly urban design with a specific focus on designing cities for people with dementia, and other mental disorders. They were also asked to identify where there is an intent to prioritise ageing and the mental health of older persons in urban planning and design, any known guidelines and policies currently in place.

It is acknowledged that further depth of analysis could have been gathered from interviews with people living with dementia and their carers, however, due to the time limitations of this study were not able to be completed.

Portrait of the state of mental health in Sydney’s older residents

,Overview of mental health - Australia-wide

At a national level, Australians are living longer and have more years in good health. Key findings from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2020), however, show there are disparities across some population groups in the status of health for older Australians and their health outcomes.

Across the nation, it is estimated that 20% of Australians had a mental or behavioural condition, and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, this number rises to 24% of the population (AIHW, 2020). It is noted that these estimates are pre-COVID-19 statistics and the lockdowns in Sydney during 2020 and 2021 have contributed to mental health being recognised as a more acute issue. A study undertaken by Australian Broadcasting Commission and Vox Pop Labs (2020) has noted some significant changes in self-reported wellbeing in 2020 since COVID-19 became more pronounced in Australia. The population reporting poor mental health more than doubled from March 2020 to April 2020, and the number of people feeling frequent despair had tripled in the same period. The study also notes that there has been an increase in the number of Australians feeling a sense of solidarity (ABC, 2020).

The AIHW (2020) has identified some significant issues that have been attributed to affecting a person’s mental health including extreme weather events. For example, it has been estimated that 10% of Australian adults considered their home or property to be directly threatened by the 2019-20 bushfire season and more than 50% of people experienced anxiety or worry owing to the bushfires (AIWH, 2020). Homelessness, financial housing stress and homes in poor physical condition are other factors that can be attributed to psychological stress (AIWH, 2020). Estimates across Australia reveal approximately 116,000 Australians are homeless, 1 million live in financial housing stress and almost the same number are living in housing that is in poor physical condition (AIWH, 2020).

Just over 10% of all Australians provide unpaid care to people with a disability and older Australians (ABS, 2018). Primary carers make up one third of this population, with primary carers themselves often living with a disability (37.5% of primary carers). Carers Australia (2019) highlights that “carers, including mental health carers often provide care at considerable cost to their own wellbeing, impacting their health, peace of mind, financial security and the opportunity to pursue their own education, employment and interests.”

Older people's mental health - Australia-wide

A survey undertaken by Relationships Australia found the highest level of loneliness exists among those aged 80 years and over, noting the harmful impact of social isolation and loneliness to mental and physical health (AIHM, 2019).

It is estimated that there are between 400,000 and 459,000 Australians living with dementia, and in 2018 dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease) was the second leading cause of death among people aged 75 and over. For females in the same age group, it was the leading cause of death (AIHW, 2020). It has been estimated that up to one third of people diagnosed with dementia will experience moderate to severe behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia which include major depression, severe aggression including physical and verbal, severe agitation, screaming and psychosis, resulting in a significant burden of care for both community carers and residential aged care facility staff (NSW Health Sydney Local Health District, 2013).

Across Australia, in 2010, 12% of people with dementia were from a Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) background (Xiao et al., 2013). There is recognition that people from CALD backgrounds are underrepresented in dementia research and relevant data on ethnicity is not routinely gathered (National Institute for Dementia Research, 2019). There is evidence that CALD Australians are diagnosed with dementia later than non-CALD Australians and awareness of dementia is low in some CALD communities.

A number of studies suggest rates of dementia may be up to three to five times more common in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across remote, regional and urban Australia when compared to non-Indigenous rates, and that dementia often occurs at younger ages in these communities (Alzheimer’s Australia, 2014). In recognition of this difference, in New South Wales, some targeted programs and services focus on Aboriginal people aged 50 years or older with mental health problems, who themselves identify with the older population (NSW Health, 2020).

Dementia Australia highlights that a vast majority of older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) people have experienced discrimination from the broader community and from legal and healthcare systems. This history of discrimination and abuse can impact on health and wellbeing. Studies have shown that LGBTI people have a higher incidence of psychological distress (Dementia Australia, 2020). Although detailed data is not available, it is estimated that LGBTI people make up 11% of the Australian population, suggesting that there may be approximately 10,000 LGBTI people with dementia by 2036. Recognising the diversity of LGBTI populations, potential experiences of discrimination, as well as potential misunderstanding or limited awareness of the rights of carers, focused actions and resources are required to support access to care, awareness of particular health issues and inclusive approaches to care.

Older people's mental health - Sydney

At a state level, in New South Wales there are an estimated 157,000 people living with dementia and this number is expected to more than double by 2058 without a medical breakthrough (Dementia Australia, 2021). At a more local level, in Sydney, the estimated number of older people aged 65 and above with dementia in 2016 was 71,445 (NATSEM, 2017). For the same age group, this number is projected to increase to 93,178 in 2036 (NATSEM, 2017).

The Greater Sydney Metropolitan Region is highly culturally diverse with more than 35% of the community speaking a language other than English at home, and more than 40% of the population overall born outside of Australia (ABS, 2017). In some local government areas like Fairfield and Cumberland, more than 50% of the population’s country of birth was outside Australia (ABS, 2017). There may be significant patient barriers for CALD communities in diagnosis of mental illness and dementia and accessing care. In the Sydney Inner West area, the following actions for improvement have been identified to respond to local challenges:

Studies have shown that poverty or lower income is directly related to mental health (Isaacs et al. 2018). People with lower incomes are more likely to be frequently exposed to risk factors for psychological distress such as violence, crime, homelessness and unemployment. In addition, a study in 2018 has shown that there is “a significantly higher risk of both older males and females falling into multidimensional poverty amongst those with high psychological distress” (Callender & Schofield, 2018).

Across Sydney, as shown in the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas in 2016, there is high inequity across the Sydney Metropolitan area, with some of the least disadvantaged areas (in the Northern Subregion), and also hosting the third most disadvantaged local government area in the state, Fairfield in South West Sydney (NSW Planning & Infrastructure, n.d.). Appropriate and affordable housing in communities with accessible and affordable services are recognised as crucial by Mission Australia (2017).

At a national level, Australians are living longer and have more years in good health. Key findings from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2020), however, show there are disparities across some population groups in the status of health for older Australians and their health outcomes.

Across the nation, it is estimated that 20% of Australians had a mental or behavioural condition, and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, this number rises to 24% of the population (AIHW, 2020). It is noted that these estimates are pre-COVID-19 statistics and the lockdowns in Sydney during 2020 and 2021 have contributed to mental health being recognised as a more acute issue. A study undertaken by Australian Broadcasting Commission and Vox Pop Labs (2020) has noted some significant changes in self-reported wellbeing in 2020 since COVID-19 became more pronounced in Australia. The population reporting poor mental health more than doubled from March 2020 to April 2020, and the number of people feeling frequent despair had tripled in the same period. The study also notes that there has been an increase in the number of Australians feeling a sense of solidarity (ABC, 2020).

The AIHW (2020) has identified some significant issues that have been attributed to affecting a person’s mental health including extreme weather events. For example, it has been estimated that 10% of Australian adults considered their home or property to be directly threatened by the 2019-20 bushfire season and more than 50% of people experienced anxiety or worry owing to the bushfires (AIWH, 2020). Homelessness, financial housing stress and homes in poor physical condition are other factors that can be attributed to psychological stress (AIWH, 2020). Estimates across Australia reveal approximately 116,000 Australians are homeless, 1 million live in financial housing stress and almost the same number are living in housing that is in poor physical condition (AIWH, 2020).

Just over 10% of all Australians provide unpaid care to people with a disability and older Australians (ABS, 2018). Primary carers make up one third of this population, with primary carers themselves often living with a disability (37.5% of primary carers). Carers Australia (2019) highlights that “carers, including mental health carers often provide care at considerable cost to their own wellbeing, impacting their health, peace of mind, financial security and the opportunity to pursue their own education, employment and interests.”

Older people's mental health - Australia-wide

A survey undertaken by Relationships Australia found the highest level of loneliness exists among those aged 80 years and over, noting the harmful impact of social isolation and loneliness to mental and physical health (AIHM, 2019).

It is estimated that there are between 400,000 and 459,000 Australians living with dementia, and in 2018 dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease) was the second leading cause of death among people aged 75 and over. For females in the same age group, it was the leading cause of death (AIHW, 2020). It has been estimated that up to one third of people diagnosed with dementia will experience moderate to severe behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia which include major depression, severe aggression including physical and verbal, severe agitation, screaming and psychosis, resulting in a significant burden of care for both community carers and residential aged care facility staff (NSW Health Sydney Local Health District, 2013).

Across Australia, in 2010, 12% of people with dementia were from a Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) background (Xiao et al., 2013). There is recognition that people from CALD backgrounds are underrepresented in dementia research and relevant data on ethnicity is not routinely gathered (National Institute for Dementia Research, 2019). There is evidence that CALD Australians are diagnosed with dementia later than non-CALD Australians and awareness of dementia is low in some CALD communities.

A number of studies suggest rates of dementia may be up to three to five times more common in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across remote, regional and urban Australia when compared to non-Indigenous rates, and that dementia often occurs at younger ages in these communities (Alzheimer’s Australia, 2014). In recognition of this difference, in New South Wales, some targeted programs and services focus on Aboriginal people aged 50 years or older with mental health problems, who themselves identify with the older population (NSW Health, 2020).

Dementia Australia highlights that a vast majority of older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) people have experienced discrimination from the broader community and from legal and healthcare systems. This history of discrimination and abuse can impact on health and wellbeing. Studies have shown that LGBTI people have a higher incidence of psychological distress (Dementia Australia, 2020). Although detailed data is not available, it is estimated that LGBTI people make up 11% of the Australian population, suggesting that there may be approximately 10,000 LGBTI people with dementia by 2036. Recognising the diversity of LGBTI populations, potential experiences of discrimination, as well as potential misunderstanding or limited awareness of the rights of carers, focused actions and resources are required to support access to care, awareness of particular health issues and inclusive approaches to care.

Older people's mental health - Sydney

At a state level, in New South Wales there are an estimated 157,000 people living with dementia and this number is expected to more than double by 2058 without a medical breakthrough (Dementia Australia, 2021). At a more local level, in Sydney, the estimated number of older people aged 65 and above with dementia in 2016 was 71,445 (NATSEM, 2017). For the same age group, this number is projected to increase to 93,178 in 2036 (NATSEM, 2017).

The Greater Sydney Metropolitan Region is highly culturally diverse with more than 35% of the community speaking a language other than English at home, and more than 40% of the population overall born outside of Australia (ABS, 2017). In some local government areas like Fairfield and Cumberland, more than 50% of the population’s country of birth was outside Australia (ABS, 2017). There may be significant patient barriers for CALD communities in diagnosis of mental illness and dementia and accessing care. In the Sydney Inner West area, the following actions for improvement have been identified to respond to local challenges:

- The need to improve the knowledge and understanding of dementia for people from CALD backgrounds

- The need to improve community awareness and links to services that support people living with dementia and their carers

- A lack of peer support and social inclusion opportunities for people living with dementia and their carers

- Need to reduce carer pressure and stress (Sydney Local Health District, 2012).

Studies have shown that poverty or lower income is directly related to mental health (Isaacs et al. 2018). People with lower incomes are more likely to be frequently exposed to risk factors for psychological distress such as violence, crime, homelessness and unemployment. In addition, a study in 2018 has shown that there is “a significantly higher risk of both older males and females falling into multidimensional poverty amongst those with high psychological distress” (Callender & Schofield, 2018).

Across Sydney, as shown in the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas in 2016, there is high inequity across the Sydney Metropolitan area, with some of the least disadvantaged areas (in the Northern Subregion), and also hosting the third most disadvantaged local government area in the state, Fairfield in South West Sydney (NSW Planning & Infrastructure, n.d.). Appropriate and affordable housing in communities with accessible and affordable services are recognised as crucial by Mission Australia (2017).

Mind the GAPS framework

Applying the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health’s Mind the GAPS Framework, we begin to consider the impact of urban design and planning on mental health at the city level through the following themes: green places; active places; pro-social places; and safe places. We have supplemented green places with blue places. These aspects of place, when done well, increase older people’s ability to participate in their community.

We have also explored these urban design themes from the perspectives of Sydneysiders themselves, drawing upon a 2019 survey by Ipsos (Committee for Sydney, 2019) to understand the attitudes of Sydneysiders to ageing and retirement as in relation to the built environment.

Before applying the ‘Mind the GAPS Framework’, we have highlighted some high-level findings from the survey:

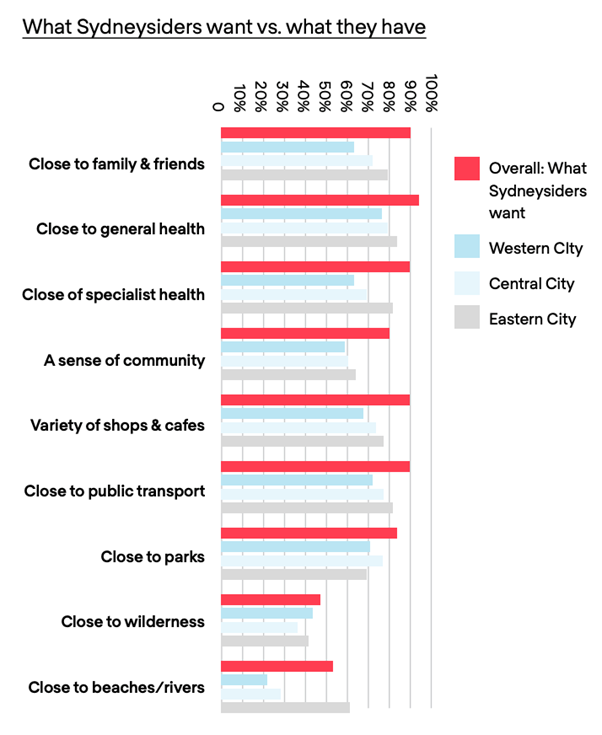

The following graph highlights the aspects of place and community that Sydneysiders desire in their older age and retirement. Being close to general health facilities was the number one priority identified by survey respondents, closely followed by proximity to family and friends, proximity to specialist health facilities, being near a variety of shops and cafes and being in a location supported by public transport (Committee for Sydney, 2019). The findings also distinguish between the needs of those living in the Eastern, Central and Western cities of Sydney.

We have also explored these urban design themes from the perspectives of Sydneysiders themselves, drawing upon a 2019 survey by Ipsos (Committee for Sydney, 2019) to understand the attitudes of Sydneysiders to ageing and retirement as in relation to the built environment.

Before applying the ‘Mind the GAPS Framework’, we have highlighted some high-level findings from the survey:

- When asked whether their suburb caters to retirees and older people, almost 50% of those surveyed responded that it did not

- More than half of people that rated their suburb poorly in catering to retirees and older people expect to leave the area in retirement. The majority of those that rate their area as catering well expect to remain in their area during retirement

- In retirement, 9 in 10 people want to live close to general and specialist health services, public transport, friends and family and a variety of shops and cafes.

The following graph highlights the aspects of place and community that Sydneysiders desire in their older age and retirement. Being close to general health facilities was the number one priority identified by survey respondents, closely followed by proximity to family and friends, proximity to specialist health facilities, being near a variety of shops and cafes and being in a location supported by public transport (Committee for Sydney, 2019). The findings also distinguish between the needs of those living in the Eastern, Central and Western cities of Sydney.

Figure 3 Priorities for Sydney residents in older age and retirement. Source: Committee for Sydney, 2019

Green and blue places

Across Sydney, the Committee for Sydney (2019) survey highlights that 90% of all respondents noted proximity to parks as a key desire in ageing in place. The experiences of accessibility to open space, however, vary across Sydney. Overall, around 65% of people living in Greater Sydney are within a 400-metre walk of open space. This is higher in the Eastern City District at 77% than Western City District at 58% (Greater Sydney Commission, 2020).

The disparity in walkability of communities in Sydney is a crucial conversation about public space. The concept of streets as critical components of the public open space network has been highlighted by the work of Project for Public Spaces (PPS) (2015). Not only for movement between places, but streets also are multifunctional and spaces where “we routinely encounter people who are different from ourselves” (PPS, 2015).

The value of green and blue spaces in Sydney, particularly local spaces, has been demonstrated in COVID-19 where one survey noted that 78% of respondents said local parks had been “especially useful” or “appreciated more” during COVID-19 restrictions (NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, 2020).

Quality of spaces and the facilities and services available to meet user needs are crucial elements to understanding and enhancing people’s experiences of greenspace. In St Leonards in Sydney’s North for example, Gore Hill Park (see Figure 4) has been upgraded with a playground for all abilities that sits alongside a basketball court, fitness station, football field for competitions and training of younger groups and adults, and a flat walking pathway around the field. The design considers multiple user groups and designs in the opportunity for mixing generations and activities.

Greenspaces have been recognised widely to contribute to reducing temperatures as places across Australia are facing heatwaves amongst other extreme weather events. Heatwaves have shown that older people are one of the most at-risk groups during a heatwave and they were linked to a raised mortality rate for older Australians by 28% (Aged Care Guide, 2018). As with walkability, the tree canopy cover distribution varies across the Sydney area. The NSW Government has set a target to increase tree canopy cover across Greater Sydney to 40 per cent.

Blue spaces also show potential health benefits from living near or deliberately visiting blue spaces, primarily on mental health and the promotion of physical activity (Britton et al, 2020). Across Sydney, government and developers seek to regenerate and renew waterfront areas to bring greater value from blue spaces including enhancing local economy, improving climate resilience from integrated flood management action, and enabling greater engagement from the public with waterways.

The NSW Government has an ambition to establish a continuous public foreshore walk along Sydney Harbour. The opening of Barangaroo in Sydney’s Eastern CBD brings a continuous 11-kilometre walkway to the public. In Parramatta, there are plans to connect the city to Parramatta River, including enabling swimmable or splash-able areas, and greater activation and engagement with the water.

Valuing relationships with land and water enables a greater opportunity to acknowledge and learn from Aboriginal people and caring for Country. NSW Government recognises the need to work differently and make decisions that prioritise First Nations people, as they highlight that “First Peoples, have been caring for Country in a sustainable way, passing on this continuing responsibility and custodianship to countless generations. As a consequence, profound relationships have been forged with Mother Earth and other ancestral beings which underpin this culture of caring for Country” (Government Architect NSW, 2020).

The disparity in walkability of communities in Sydney is a crucial conversation about public space. The concept of streets as critical components of the public open space network has been highlighted by the work of Project for Public Spaces (PPS) (2015). Not only for movement between places, but streets also are multifunctional and spaces where “we routinely encounter people who are different from ourselves” (PPS, 2015).

The value of green and blue spaces in Sydney, particularly local spaces, has been demonstrated in COVID-19 where one survey noted that 78% of respondents said local parks had been “especially useful” or “appreciated more” during COVID-19 restrictions (NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, 2020).

Quality of spaces and the facilities and services available to meet user needs are crucial elements to understanding and enhancing people’s experiences of greenspace. In St Leonards in Sydney’s North for example, Gore Hill Park (see Figure 4) has been upgraded with a playground for all abilities that sits alongside a basketball court, fitness station, football field for competitions and training of younger groups and adults, and a flat walking pathway around the field. The design considers multiple user groups and designs in the opportunity for mixing generations and activities.

Greenspaces have been recognised widely to contribute to reducing temperatures as places across Australia are facing heatwaves amongst other extreme weather events. Heatwaves have shown that older people are one of the most at-risk groups during a heatwave and they were linked to a raised mortality rate for older Australians by 28% (Aged Care Guide, 2018). As with walkability, the tree canopy cover distribution varies across the Sydney area. The NSW Government has set a target to increase tree canopy cover across Greater Sydney to 40 per cent.

Blue spaces also show potential health benefits from living near or deliberately visiting blue spaces, primarily on mental health and the promotion of physical activity (Britton et al, 2020). Across Sydney, government and developers seek to regenerate and renew waterfront areas to bring greater value from blue spaces including enhancing local economy, improving climate resilience from integrated flood management action, and enabling greater engagement from the public with waterways.

The NSW Government has an ambition to establish a continuous public foreshore walk along Sydney Harbour. The opening of Barangaroo in Sydney’s Eastern CBD brings a continuous 11-kilometre walkway to the public. In Parramatta, there are plans to connect the city to Parramatta River, including enabling swimmable or splash-able areas, and greater activation and engagement with the water.

Valuing relationships with land and water enables a greater opportunity to acknowledge and learn from Aboriginal people and caring for Country. NSW Government recognises the need to work differently and make decisions that prioritise First Nations people, as they highlight that “First Peoples, have been caring for Country in a sustainable way, passing on this continuing responsibility and custodianship to countless generations. As a consequence, profound relationships have been forged with Mother Earth and other ancestral beings which underpin this culture of caring for Country” (Government Architect NSW, 2020).

Figure 4 Intergenerational family gathering at a Sydney park. Source: Safiah Moore.

Active Places

The World Alzheimer Report (2014) highlighted that high blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes and overweight/obesity are plausibly linked to risks for dementia. A study in 2020 (De La Rosa et al, 2020) further highlighted that physical activity and healthy diet are protective factors of vascular dementia and Alzheimer disease. Walking or public transport is a fundamental piece of the city to support older people, including those across many stages of living with a dementia diagnosis and their carers. Inclusive design of walking or public transport infrastructure (both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure) can support movement and engagement and maintain a person’s health and wellbeing (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2020).

The Greater Sydney Commission highlights that 34% of people living in Greater Sydney are within a 10-minute walk of a centre that has at minimum a supermarket of 1,000 square metres. "This accessibility is uneven across Greater Sydney with far higher levels of access to local and larger centres with levels of over 60 per cent in the Eastern City District, compared with around 20 per cent in the Western City and Central City districts” (Greater Sydney Commission, 2020). The disparity in accessibility across Sydney highlights priority areas to focus action, in particular when viewing multiple risk factors of mental health including socio economic status.

Outdoor gyms, if designed appropriately with appropriate support can encourage physical activity. In a study to inform design for an outdoor gym in Sydney’s Eastern City, it was found that outdoor gyms designed with inputs from the health professional network (including exercise physiologist) alongside professionally instructed exercise sessions designed for older adults were successful in engaging older adults in outdoor gym use (Scott et al, 2014).

The Greater Sydney Commission highlights that 34% of people living in Greater Sydney are within a 10-minute walk of a centre that has at minimum a supermarket of 1,000 square metres. "This accessibility is uneven across Greater Sydney with far higher levels of access to local and larger centres with levels of over 60 per cent in the Eastern City District, compared with around 20 per cent in the Western City and Central City districts” (Greater Sydney Commission, 2020). The disparity in accessibility across Sydney highlights priority areas to focus action, in particular when viewing multiple risk factors of mental health including socio economic status.

Outdoor gyms, if designed appropriately with appropriate support can encourage physical activity. In a study to inform design for an outdoor gym in Sydney’s Eastern City, it was found that outdoor gyms designed with inputs from the health professional network (including exercise physiologist) alongside professionally instructed exercise sessions designed for older adults were successful in engaging older adults in outdoor gym use (Scott et al, 2014).

Pro-Social Places

Research shows that positive mental health for older adults is linked to frequent social interactions (Winningham & Pike, 2007; Saarloos et al. 2009) in Gilbert and Galea,) as “without constant reminders of who they are, a person living with dementia loses their sense of identity” (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2020). There is a need for multiple spaces both to be alone and with others for people living with dementia. Spaces with variety, for quiet conversation, time to be alone, gathering with others, or spaces to overlook other activities provide stimulation and engagement including for intergenerational engagement with a low barrier to entry. This includes providing public or free spaces or spaces to ‘bring your own’ refreshments and activities without the pressure to need to purchase something to enjoy and be active in a space.

The D-Cafe in Sydney is a weekly social gathering at a local cafe for people living with dementia, their carers and family and friends. Across the world, dementia cafés have “shown to provide a major and positive impact on the quality of life of people living with dementia and their family carers” (Alzheimer’s Australia, 2013). Alzheimer’s Australia also provides a ‘Dementia Cafe toolkit’ for others to start up D-cafe’s in their own locations. The success of the D-Cafe highlights the importance of programs provided by local service providers and support groups that are enabled by the availability and flexibility of pro-social spaces.

Facilities within pro-social spaces require deliberate design including public toilets. In a review of public toilet design across Australia, research has proposed that a national approach to public toilets is needed to increase accessibility and participation in social, economic and civic life (Australian Local Government Association, 2021). For people living with dementia, clear signage with limited visual distraction is crucial to provide comfort for people living with dementia and their carers to participate in public social spaces.

Design in pro-social spaces for familiarity, reflecting needs and identity is particularly important to CALD communities and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples including people living with dementia and their carers. In a study for Greater Sydney examining cultural value and place, it is noted that there is a significant risk for the ‘sense of place, unique vernacular, feelings of identity and belonging, and the story of Sydney [to be] lost or become indistinct” (Clarke et al. 2018). Retaining and celebrating heritage, artefacts and reflecting stories of place or Country, as well as specific design features (e.g. cooking facilities or spaces to cater larger gatherings) are opportunities for design as well as the process for design of pro-social spaces.

The D-Cafe in Sydney is a weekly social gathering at a local cafe for people living with dementia, their carers and family and friends. Across the world, dementia cafés have “shown to provide a major and positive impact on the quality of life of people living with dementia and their family carers” (Alzheimer’s Australia, 2013). Alzheimer’s Australia also provides a ‘Dementia Cafe toolkit’ for others to start up D-cafe’s in their own locations. The success of the D-Cafe highlights the importance of programs provided by local service providers and support groups that are enabled by the availability and flexibility of pro-social spaces.

Facilities within pro-social spaces require deliberate design including public toilets. In a review of public toilet design across Australia, research has proposed that a national approach to public toilets is needed to increase accessibility and participation in social, economic and civic life (Australian Local Government Association, 2021). For people living with dementia, clear signage with limited visual distraction is crucial to provide comfort for people living with dementia and their carers to participate in public social spaces.

Design in pro-social spaces for familiarity, reflecting needs and identity is particularly important to CALD communities and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples including people living with dementia and their carers. In a study for Greater Sydney examining cultural value and place, it is noted that there is a significant risk for the ‘sense of place, unique vernacular, feelings of identity and belonging, and the story of Sydney [to be] lost or become indistinct” (Clarke et al. 2018). Retaining and celebrating heritage, artefacts and reflecting stories of place or Country, as well as specific design features (e.g. cooking facilities or spaces to cater larger gatherings) are opportunities for design as well as the process for design of pro-social spaces.

Safe places

Overall in Australia, older people are less likely than younger people to experience victimisation for personal offences (robbery, assault etc.), however, it is recognised that crime can impact greatly on some older people’s lives and some groups of older people are more afraid of crime than others (AIC, 2013). Research has also shown that “older people who are most active and involved in their communities, or who are made to feel involved, are least likely to be anxious about crime” (AIC, 2013).

Feeling unsafe in an environment has the potential to impact social connections and activity across any age group. An Alzheimer’s Australia (2014) survey highlighted that 57% of people surveyed with dementia were afraid of becoming lost in their local community. Elements in the built environment that enable orientation and familiarity are crucial components for people living with dementia in the community.

To support road safety, in areas of high concentration of older people, slower road environments can be implemented (40 km/hr zones) across NSW. An evaluation in Sydney highlighted that 40 km/h speed limits in high pedestrian areas found they were effective in improving safety, with a reduction of approximately 33% in crashes causing fatalities and serious injuries (City of Sydney, 2020). Slower road speeds support greater outcomes for all users including children as well as bring amenity benefits.

Embedding symbols and practice of cultural safety within urban design and planning are important elements to encourage engagement and access to spaces and services that improve wellbeing. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, cultural safety is about:

Feeling unsafe in an environment has the potential to impact social connections and activity across any age group. An Alzheimer’s Australia (2014) survey highlighted that 57% of people surveyed with dementia were afraid of becoming lost in their local community. Elements in the built environment that enable orientation and familiarity are crucial components for people living with dementia in the community.

To support road safety, in areas of high concentration of older people, slower road environments can be implemented (40 km/hr zones) across NSW. An evaluation in Sydney highlighted that 40 km/h speed limits in high pedestrian areas found they were effective in improving safety, with a reduction of approximately 33% in crashes causing fatalities and serious injuries (City of Sydney, 2020). Slower road speeds support greater outcomes for all users including children as well as bring amenity benefits.

Embedding symbols and practice of cultural safety within urban design and planning are important elements to encourage engagement and access to spaces and services that improve wellbeing. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, cultural safety is about:

- Shared respect, shared meaning and shared knowledge

- The experience of learning together with dignity and truly listening

- Strategic and institutional reform to remove barriers to the optimal health, wellbeing and safety of Aboriginal people

- Individuals, organisations and systems ensuring their cultural values do not negatively impact on Aboriginal peoples, including addressing the potential for unconscious bias, racism and discrimination

- Individuals, organisations and systems ensuring self-determination for Aboriginal people (State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services, 2020).

Perceived priority of age and dementia-friendly urban planning and design in Sydney

Interviews have identified the extent to which mental health and ageing is considered in urban design and planning, the degree to which policies are inclusive of older people with varying needs and capacities and its prioritisation in Sydney.

Figure 5: Architects and urban designers in a workshop. Source © Grimshaw

The priority that architects, city planners, policy makers in Sydney give to help improve experiences for older persons and those with dementia

“Considering physical and mental health in the design of the built environment is becoming more common but it’s typically nested under a larger umbrella of liveability.” (Urban planner)

“Organisations, like The Heart Foundation and NSW Health (in the position of policy makers), advocate for the improvement of physical and mental health through the design of cities and places, but there is a lack of an active age-friendly-cities agenda.” (Urban planner)

“Age friendliness is often seen to benefit from other initiatives – universal design, sustainability and designing for women for example - but less so is it given its own focus.” (Urban designer)

“Cities have been designed and continue to be largely designed as though the “default human” is an early 40s able-bodied white cisgender male.” (Urban planner)

“The impression that the needs of older persons and those with dementia is a “niche” sector of public health might factor into age-friendliness not always being front of mind for city planners and designers. There needs to be a shift from attributing responsibility for this issue to healthcare facilities/healthcare providers/aged care facilities to a shared responsibility of a vulnerable, growing section of the population.” (Urban planner)

“Local government’s Local Strategic Planning Statements rarely call out this agenda; it’s not expressed in their vision of what they want in their built environment. More broadly housing and jobs are the big criteria” (Urban designer)

Impacts of social isolation have been further highlighted by COVID-19

“The Royal Commission on Aged Care has placed ageing as a priority, including recognition of risks of social isolation in older people.” (Health practitioner)

“Older people with mental health issues are socially isolated due to embarrassment from patients themselves not being able to remember events or people. Peer groups also start to leave them out – as other people are anxious about not being able to deal with or know how to include people with dementia.” (Health practitioner)

Intergenerational spaces and intergenerational programs for wellness and building greater understanding

“Design for intergenerational care, for example programs like ‘Aged Care Home for 4 Year Olds’ can be learnt from and applied in the built environment. This could include of childcare facilities in close proximity to aged care facilities – and designing in more opportunities for mixing of groups.” (Health practitioner)

“Preschool outreach for example ‘incursions’ for age care residents to read books with younger people, can support patients with depression, may not be appropriate for patient with dementia.” (Health practitioner)

“Housing that provides visual access into the daily life of their neighbourhoods is important - eyes on the street to engage with activity including people of different ages.” (International development practitioner)

Personalised design - tailoring for mobility, function and interest

“Improving mental health and happiness for older people works at various levels. From early stages of planning to set up the structure of places to designing the distances between key facilities and homes...to designing buildings, infrastructure and then at the detailed design for seating areas, toilets and lighting.” (Architect)

“We need to see design from different perspectives. The default for design is a person who is able, fit, health, young and generally male.” (Architect)

“Measures that improve accessibility to activities, to go to places, safely and reducing transport time when not in an acute caring environment are important components of city design.” (Health practitioner)

“Being asked, being involved, having experience and knowledge respected is a crucial component of good design with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.” (International development practitioner)

Accessible and active spaces in the public enable independence and contribute to reducing risk factors

“There is an increasing trend to provide more access to gardens, playgrounds and community centres. There is a need for flexible spaces for a range of programs: programs suitable for older and younger age groups to mix, dancing and other diversional therapy.” (Health practitioner)

“Age care facilities that are located close to high streets ensure that residents participate more in public life. For example, the local park becomes their backyard and meals can be eaten in a café, not just a sterile cafeteria in a purpose-built facility.” (Urban designer)

“Biophilic design and greater connection to nature is calming and comforting.” (Urban designer)

“There are some limitations to broader design currently. Whilst internally, aged care facilities may be provided for, these may be separated from broader city service. E.g., prioritise car access, and limited facilities for walkability.” (Health practitioner)

“Providing opportunities for new activities and environments is good to support people with dementia. Programs with new activities – movie, show – where they don’t have to rely on a previous memory or experience can be inviting, more comfortable for dementia patients.” (Health practitioner)

Designing for carers

“Carers and supporters are predominantly, in Australia, kinship/family carers, friends and unpaid carers. Instances of carer stress need to be considered, and designed for including measures for wellbeing.” (General Practitioner)

“Design of public spaces for diversity can improving physical, mental health for older people e.g., community gardens help with providing environments for intimate connections, library spaces with smaller meeting rooms provide quiet interaction space and larger meeting spaces to network with broader groups including group type therapy which is important for carers.” (Health practitioner)

Familiar landscapes - people, architecture, landmarks to create greater comfort

“Older people aging in place may be experiencing some deterioration whilst remaining in community. A network of community members - e.g., pharmacist or grocer can be important for looking out for others and offering support when a person living with dementia may become disoriented.” (Health practitioner)

“Components of familiarity, physically and reflecting a person’s cultural background can support older people with dementia.” (Health practitioner)

“City of Sydney’s City of Villages concept that seeks to build community through improvements to local facilities including parks, events and public art as well as walkable, rideable streets. The focus on villages from a spatial structure leads to the development of community and familiarity that is very important for older people and people living with dementia.” (Architect)

“Celebrating heritage elements can be an important part of retaining familiarity in the urban realm.” (Architect)

“There are design principles established and applied in aged care environments that can be extrapolated/ extended into public places. Designing for distinct spaces – through landmarks, colours help with orientation and familiarity of spaces as confusion is a symptom of dementia.” (Health practitioner)

“Stories of place and how they get translated into the urban realm is important for identity and it provides an opportunity for building wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.” (International development practitioner)

“There can be lessons from designs from Aboriginal health facilities. Designs seek to connect to the outdoors with strong references to native landscapes.” (International development practitioner)

In need of slow spaces and services

“Quietness and slower paced services including access to transport and facilities are important.” (Health practitioner)

“A lot of urban design and planning focuses on promoting activity and vibrancy - both from economic development and wellbeing benefits - quiet, reflective and slow needs to also be part of design aspirations for inclusive spaces that promote wellness.” (Urban planner)

“There are general trends in the way that major transport stations are planned - to create more open and expansive spaces, for example Wynyard Station upgrade has a grand entrance that could invite a slower pace.” (Transport planner)

Capacity building and toolkits for practitioners to shift decision making to value health and skillsets of older people

“Traditional economic tools like cost benefit analysis do not capture benefits to older people, as they are no longer in the workforce.” (Health economist)

“Policy is good, but policy or regulation has some perceptions of red tape or restrictions being enforced. Approaches like ‘Age-n-dem’ in Moonee Valley City Council, promote an outcome led approach that goes beyond compliance of minimum standards.” (Architect)

More cross sectoral planning and design is required to promote independence and keep people in the community as long as possible

“Actions are required to face intersectoral challenges, to break down barriers across sectors and organisations to deliver outcomes.” (Health Economist)

“COVID - 19 response in Australia has seen a recent cross sectoral response, health, police working together to support tracing and pop-up clinics, and widespread communication to the public.” (Health Economist)

“In the health sector, ageing is recognised as a priority. With the increase in ageing the need for increased services over the next 5 - 10 years is being actively planned across the primary health network and private health sector.” (Health practitioner)

“A greater understanding can make a big difference. Knowledge can provide the baseline for designers to be creative, see benefits and opportunities for designing for inclusion of older people with mental conditions.” (Architect)

“For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, definitions of health and wellbeing encompasses social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the community. Although these can’t be appropriated, greater acknowledgement of ways of supporting wellbeing like connection to places, spiritual wellbeing can expand our approaches to supporting healthy communities.” (International development practitioner)

Learning opportunities for communities and families to build greater capacity across the network

“Greater awareness from community about dementia, stages of dementia and opportunities for care for and support dementia patients may be able to be incorporated into awareness campaigns/design.” (Health practitioner)

“We need programs to make ageing sexy - reframing this age period as an exciting time of life.” (Architect)

“There needs to be broader understanding of stages of dementia and a focus on retaining people living with dementia ‘in place.” (Transport planner)

Interrelationships between age-friendly design and other key city agendas need to be showcased

“As complex systems, there are many perspectives for designers to consider in a city. It is often hard to see the needs of older people and those living with dementia within other priorities. However, designing for older people and those with mental conditions is not necessarily separate, it is about having sophisticated knowledge to understand the interrelationships.” (Architect)

“It would be great to have references for where multiple city agendas align, including wellness for older people and people living with dementia, and then outline what is common, and considerations that may need specific input or deliberate design to guide investment in more time and thinking.” (Transport planner)

“Considering physical and mental health in the design of the built environment is becoming more common but it’s typically nested under a larger umbrella of liveability.” (Urban planner)

“Organisations, like The Heart Foundation and NSW Health (in the position of policy makers), advocate for the improvement of physical and mental health through the design of cities and places, but there is a lack of an active age-friendly-cities agenda.” (Urban planner)

“Age friendliness is often seen to benefit from other initiatives – universal design, sustainability and designing for women for example - but less so is it given its own focus.” (Urban designer)

“Cities have been designed and continue to be largely designed as though the “default human” is an early 40s able-bodied white cisgender male.” (Urban planner)

“The impression that the needs of older persons and those with dementia is a “niche” sector of public health might factor into age-friendliness not always being front of mind for city planners and designers. There needs to be a shift from attributing responsibility for this issue to healthcare facilities/healthcare providers/aged care facilities to a shared responsibility of a vulnerable, growing section of the population.” (Urban planner)

“Local government’s Local Strategic Planning Statements rarely call out this agenda; it’s not expressed in their vision of what they want in their built environment. More broadly housing and jobs are the big criteria” (Urban designer)

Impacts of social isolation have been further highlighted by COVID-19

“The Royal Commission on Aged Care has placed ageing as a priority, including recognition of risks of social isolation in older people.” (Health practitioner)

“Older people with mental health issues are socially isolated due to embarrassment from patients themselves not being able to remember events or people. Peer groups also start to leave them out – as other people are anxious about not being able to deal with or know how to include people with dementia.” (Health practitioner)

Intergenerational spaces and intergenerational programs for wellness and building greater understanding

“Design for intergenerational care, for example programs like ‘Aged Care Home for 4 Year Olds’ can be learnt from and applied in the built environment. This could include of childcare facilities in close proximity to aged care facilities – and designing in more opportunities for mixing of groups.” (Health practitioner)

“Preschool outreach for example ‘incursions’ for age care residents to read books with younger people, can support patients with depression, may not be appropriate for patient with dementia.” (Health practitioner)

“Housing that provides visual access into the daily life of their neighbourhoods is important - eyes on the street to engage with activity including people of different ages.” (International development practitioner)

Personalised design - tailoring for mobility, function and interest

“Improving mental health and happiness for older people works at various levels. From early stages of planning to set up the structure of places to designing the distances between key facilities and homes...to designing buildings, infrastructure and then at the detailed design for seating areas, toilets and lighting.” (Architect)

“We need to see design from different perspectives. The default for design is a person who is able, fit, health, young and generally male.” (Architect)

“Measures that improve accessibility to activities, to go to places, safely and reducing transport time when not in an acute caring environment are important components of city design.” (Health practitioner)

“Being asked, being involved, having experience and knowledge respected is a crucial component of good design with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.” (International development practitioner)

Accessible and active spaces in the public enable independence and contribute to reducing risk factors

“There is an increasing trend to provide more access to gardens, playgrounds and community centres. There is a need for flexible spaces for a range of programs: programs suitable for older and younger age groups to mix, dancing and other diversional therapy.” (Health practitioner)

“Age care facilities that are located close to high streets ensure that residents participate more in public life. For example, the local park becomes their backyard and meals can be eaten in a café, not just a sterile cafeteria in a purpose-built facility.” (Urban designer)

“Biophilic design and greater connection to nature is calming and comforting.” (Urban designer)

“There are some limitations to broader design currently. Whilst internally, aged care facilities may be provided for, these may be separated from broader city service. E.g., prioritise car access, and limited facilities for walkability.” (Health practitioner)

“Providing opportunities for new activities and environments is good to support people with dementia. Programs with new activities – movie, show – where they don’t have to rely on a previous memory or experience can be inviting, more comfortable for dementia patients.” (Health practitioner)

Designing for carers

“Carers and supporters are predominantly, in Australia, kinship/family carers, friends and unpaid carers. Instances of carer stress need to be considered, and designed for including measures for wellbeing.” (General Practitioner)

“Design of public spaces for diversity can improving physical, mental health for older people e.g., community gardens help with providing environments for intimate connections, library spaces with smaller meeting rooms provide quiet interaction space and larger meeting spaces to network with broader groups including group type therapy which is important for carers.” (Health practitioner)

Familiar landscapes - people, architecture, landmarks to create greater comfort

“Older people aging in place may be experiencing some deterioration whilst remaining in community. A network of community members - e.g., pharmacist or grocer can be important for looking out for others and offering support when a person living with dementia may become disoriented.” (Health practitioner)

“Components of familiarity, physically and reflecting a person’s cultural background can support older people with dementia.” (Health practitioner)

“City of Sydney’s City of Villages concept that seeks to build community through improvements to local facilities including parks, events and public art as well as walkable, rideable streets. The focus on villages from a spatial structure leads to the development of community and familiarity that is very important for older people and people living with dementia.” (Architect)

“Celebrating heritage elements can be an important part of retaining familiarity in the urban realm.” (Architect)

“There are design principles established and applied in aged care environments that can be extrapolated/ extended into public places. Designing for distinct spaces – through landmarks, colours help with orientation and familiarity of spaces as confusion is a symptom of dementia.” (Health practitioner)

“Stories of place and how they get translated into the urban realm is important for identity and it provides an opportunity for building wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.” (International development practitioner)

“There can be lessons from designs from Aboriginal health facilities. Designs seek to connect to the outdoors with strong references to native landscapes.” (International development practitioner)

In need of slow spaces and services

“Quietness and slower paced services including access to transport and facilities are important.” (Health practitioner)

“A lot of urban design and planning focuses on promoting activity and vibrancy - both from economic development and wellbeing benefits - quiet, reflective and slow needs to also be part of design aspirations for inclusive spaces that promote wellness.” (Urban planner)

“There are general trends in the way that major transport stations are planned - to create more open and expansive spaces, for example Wynyard Station upgrade has a grand entrance that could invite a slower pace.” (Transport planner)

Capacity building and toolkits for practitioners to shift decision making to value health and skillsets of older people

“Traditional economic tools like cost benefit analysis do not capture benefits to older people, as they are no longer in the workforce.” (Health economist)

“Policy is good, but policy or regulation has some perceptions of red tape or restrictions being enforced. Approaches like ‘Age-n-dem’ in Moonee Valley City Council, promote an outcome led approach that goes beyond compliance of minimum standards.” (Architect)

More cross sectoral planning and design is required to promote independence and keep people in the community as long as possible

“Actions are required to face intersectoral challenges, to break down barriers across sectors and organisations to deliver outcomes.” (Health Economist)

“COVID - 19 response in Australia has seen a recent cross sectoral response, health, police working together to support tracing and pop-up clinics, and widespread communication to the public.” (Health Economist)

“In the health sector, ageing is recognised as a priority. With the increase in ageing the need for increased services over the next 5 - 10 years is being actively planned across the primary health network and private health sector.” (Health practitioner)

“A greater understanding can make a big difference. Knowledge can provide the baseline for designers to be creative, see benefits and opportunities for designing for inclusion of older people with mental conditions.” (Architect)

“For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, definitions of health and wellbeing encompasses social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the community. Although these can’t be appropriated, greater acknowledgement of ways of supporting wellbeing like connection to places, spiritual wellbeing can expand our approaches to supporting healthy communities.” (International development practitioner)

Learning opportunities for communities and families to build greater capacity across the network

“Greater awareness from community about dementia, stages of dementia and opportunities for care for and support dementia patients may be able to be incorporated into awareness campaigns/design.” (Health practitioner)

“We need programs to make ageing sexy - reframing this age period as an exciting time of life.” (Architect)

“There needs to be broader understanding of stages of dementia and a focus on retaining people living with dementia ‘in place.” (Transport planner)

Interrelationships between age-friendly design and other key city agendas need to be showcased

“As complex systems, there are many perspectives for designers to consider in a city. It is often hard to see the needs of older people and those living with dementia within other priorities. However, designing for older people and those with mental conditions is not necessarily separate, it is about having sophisticated knowledge to understand the interrelationships.” (Architect)

“It would be great to have references for where multiple city agendas align, including wellness for older people and people living with dementia, and then outline what is common, and considerations that may need specific input or deliberate design to guide investment in more time and thinking.” (Transport planner)

Policy frameworks for age and dementia-friendly urban planning and design in Sydney

There is a plethora of plans and strategies that are relevant to ageing population issues. This section provides a selection of guidance, plans and strategies that support concepts relevant to age and dementia friendly urban planning and design in Sydney.

International frameworks

The New Urban Agenda

The New Urban Agenda works to expedite the Sustainable Development Goal 11; to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable (UN Habitat, 2020). It recognizes the importance of age-responsive planning as a component of providing access and enabling the participation of all marginalized groups in every area of urban development (Ibid).

The agenda includes age responsive planning includes principles such as: “Planning for aging should be holistic and multi-sectoral; cities should begin their planning process with a vision statement” and “The built environment is an important factor for the quality of life for the elderly, as well as consistent communication and public sector service delivery” (UN Habitat, 2020 p. 16). Further it provides illustrative actions to support these principles: “(d)evelop indicators to measure the impact of aging on society, and relative access to services” and “(p)romote a culture of lifelong learning, where volunteerism and education opportunities are available for the elderly” (Ibid).

World Health Organisation, Global Age-friendly Cities: A Guide

Governments across Australia have drawn on World Health Organization (WHO) concepts to establish age-friendly city initiatives (Kendig et al, 2014).

The WHO defines an age-friendly city as one that “encourages active ageing by optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age” (2007, p1). It identifies eight areas of a city’s structures, environment, services and policies that could make a community “age-friendly.” These are outdoor spaces and buildings, transportation, housing, social participation, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, communication and information, and community support and health services.

The intent of the Guide is to “help cities see themselves from the perspective of older people, in order to identify where and how they can become more age-friendly” (2007, p.11) through a bottom-up participatory approach (Kendig et al, 2014). In practice, it is inconsistently applied across NSW state and local government strategies.

In addition to the Guide, the WHO has developed a global network for knowledge exchange between cities and communities that are committed to creating inclusive and accessible urban environments to benefit their ageing populations and as of March 2021, the WHO Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities included two local governments within the Sydney region; Liverpool City Council and Lane Cove Council.

National frameworks

Smart Cities Plan

The Federal Government’s (2016) Smart Cities Plan recognises the importance of Australia’s urban centres to economic, social and environmental wellbeing. Concepts of health (more generally) and planning are embedded in the plan through its acknowledgment of the importance of urban green spaces and investing in active transport (Kent & Thompson, 2019) and the prioritisation of infrastructure projects that meet broader economic and city objectives such as healthy environments.

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap

There is a new National Agreement that seeks to enable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and governments to work together to overcome the inequality experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and achieve life outcomes equal to all Australians (Australian Government, 2020). It builds on the 2008 framework which previously set targets to improve Indigenous education, health and employment.

Outcomes that are particularly relevant to the role of urban and planning professionals include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: enjoy long and healthy lives, enjoy high levels of social and emotional wellbeing and maintain a distinctive cultural, spiritual, physical and economic relationship with their land and waters.

State frameworks

Premier’s Priorities

In 2019, the NSW Premier identified key policy priorities to improve the quality of life of the people of NSW. These include improvements to the health system, specifically to improve service levels and outpatient care, as well as those to create a better environment. Of most relevance to the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health’s GAPS framework, specifically green places, are targets to increase the proportion of homes in urban areas within 10 minutes’ walk of quality green, open and public space by 10% by 2023; and increase the tree canopy and green cover across Greater Sydney by planting 1 million trees by 2022 (NSW Government, n.d.).

Ageing Well in NSW: Seniors Strategy 2021–2031

The NSW ageing strategy takes a whole of Government approach to working with people across the State throughout their lives to age well and to remove barriers to continued participation. The Strategy recognises the diversity of experiences of older persons and the needs of marginalised communities such as older persons from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and older persons who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex or queer for example (NSW Government, 2021).

Underpinning the Strategy are four focus areas, including living in age-friendly environments which is described as “where we adapt and improve our physical environment to foster the participation of people as they age” (NSW Government, 2021, p.12). In doing so, the Government will work to improve the built environment so older people can live in and enjoy environments, continue to improve transport systems so older people can get out and about independently and increase affordable housing options in well serviced locations (NSW Government, 2021).

Greater Sydney Region Plan, A Metropolis of Three Cities

The Greater Sydney Region Plan employs an integrated land use, transport and infrastructure planning approach across Federal, State and Local government. The Plan aspires to create three cities (Western, Central and Eastern) where the majority of residents will live within 30 minutes of their jobs, education and health facilities, services and great places.

There are a number of objectives in the Greater Sydney Region Plan that support age-friendliness, and health more generally as an explicit priority. One of the objectives of the Plan is to deliver more housing diversity and choice which the Committee for Sydney (2019) points out that for Sydney to be considered an all ages-inclusive city, this objective will need to be embraced; for example, by providing a diversity of retirement living options for our senior residents.

Older Persons Transport and Mobility Plan 2018-2022

Released in 2019, Transport for NSW’s Plan builds on the work of the ‘NSW Ageing Strategy 2016-2020’ and ‘Future Transport 2056’ and takes a ‘whole of life’ approach by understanding a person’s changing needs as they move from active ageing to older age (Transport for NSW, 2019).

Participatory methods were used to develop the Plan with older people which provides an understanding of their travel needs and mode preferences. The Plan includes a series of guiding principles that determine Transport for NSW’s approach to service provision and are supportive of age and dementia friendly planning and urban design. For example, it aims to reduce the transport disadvantage of older customers - which may be due to low income, geographical isolation and concerns for personal safety - and keep older customers active and connected with their community.

Specific reference is made to acknowledging the need to prioritise additional training for Transport for NSW’s frontline customer service staff to better support older customers and those with dementia or cognitive impairments.

NSW Government Architect office policies

A number of policies and guidelines have been developed that focus on the relationship between design of civic spaces and wellbeing by the NSW Government Architect office. These include:

Health care guidelines

A number of health care plans guidelines have been developed by NSW Health to support older people’s mental health. Guidelines such as Specialist Mental Health Services for Older People Community Model of Care Guideline (2017) recognises that the health-related support services are just one or many domain areas (including spirituality, social connectedness, leisure, occupation, personal relationships etc.) to support a person in enabling patients to “continuing to be me with a meaningful and contributing life” (NSW Health, 2018). The Model of Care highlights that partnerships are crucial to management of all aspects of treatment, care and recovery. This highlights the importance of cross sectoral partnerships to deliver outcomes.

Local government plans and strategies

The 33 councils that comprise Greater Sydney are required to give due regard to the NSW Government’s strategic plan, and any other relevant state and regional plans and strategies (Local Government NSW, 2017). To support local government in planning for an ageing population and to respond to NSW Government priorities, the Local Government Association developed ‘The Integrated Age-Friendly Planning Toolkit for Local Government in NSW’. At a local government level, components of ageing and dementia friendly planning and related issues may be included in local strategic planning statements, providing the vision and priorities for land use in the local area; and community strategic plans, giving a broader focus on achieving the long term social, environmental and economic aspirations of the community (NSW Government, n.d).