Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2021:7;7

CASE STUDY

The Square Dance in China: How Sensory Design Can Foster Inter-Generational Interaction and Improve Older Adults’ Wellbeing

Yunhua Zhu*, Yi Zhang, Yiwei Wang, Zdravko Trivic

Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore, Singapore

* Corresponding author email: [email protected]

Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore, Singapore

* Corresponding author email: [email protected]

Citation: Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Trivic Z (2021). The square dance in China: How sensory design can foster inter-generational interaction and improve older adults' wellbeing. Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 7;7

Introduction

An “aging society” refers to a region whereby the proportion of the population aged 65 and above surpasses 7% of the region’s total population, while “aged society” and “super-aged society” refers to such proportions of 15-20% and over 21%, respectively (OECD & WHO, 2020). In 2019, around 12% of Chinese population were adults were 65 of age or above, with projections to reach over 26% in 2050 (United Nations, 2019). Such a definition with a fixed threshold of ‘old age’ at age 65, however, opens up the issues of perceiving the older adults as a homogenous group, which may lead to increased age divide, as well as ageism and stigmatization against the seniors.

Seeking people that are similar to ourselves is in human nature. However, this may also widen the age gap, especially between the teenagers and the elderly. According to Hagestad and Uhlenberg (2005), age segregation occurs at three dimensions: institutional (e.g., kindergarten vs. senior care centre), spatial (student dormitories vs. nursing homes), and cultural (social media vs. face-to-face interaction). The lack of social relationships between the age groups makes the older adults rather separated from the larger society, which can result in lower knowledge exchange between generations, the loss of empathy and ageism. Ageism is a complex construct, which has three key dimensions, including cognitive (e.g., stereotyping), affective (e.g., prejudicing) and behavioural (e.g., discriminating) dimensions (Marques et al., 2020). Ageism is express either explicitly or implicitly (latently), at individual, community and institutional scales and towards others or towards oneself (Ayalon & Tesch-Romer, 2017; Iversen et al., 2009; Marques et al., 2020; North & Fiske, 2012).

In China, for example, recent societal changes revealed greater gap between the older and the younger generations, which is no longer simply a matter of differences in values and dispositions. China has historically emphasised the respect for the elderly, and many senior adults have an inherent mentality of having a “higher status”, whereby children should learn from older generations. Today's culture is, however, described as a "pre-figurative" one, which demands the reverse – that the older generations should learn from the youth (Gao & Bischoping, 2018). Moreover, many see older adults as having a dominating attitude, while also deploying a badgering interaction style, which is characterized as ill-attuned towards younger people who demand for more egalitarian modes of inter-generational interaction (Gao & Bischoping, 2018). All this led to numerous unfair reports in the media that have portrayed the older generations as backward, corrupt, demanding, and even abusive (e.g., Fauna, 2014), which further vilified the image of the older adults and intensified the conflicts between the elderly and the young.

There is, therefore, a growing need for “the definition or creation of spaces where young, middle-aged, and elderly people from all walks of life can get to know each other enough to build mutual respect, develop cooperative relationships, and reignite the norm of human-heartedness” (Braithwaite, 2002, p. 332). In response, this small design-led study focuses on ‘square dance’, a popular activity among older adults in China, yet recently banned in many cities across China. Our aim is two-fold: (1) to examine ‘square dance’ as an acceptable and healthful activity for older adults; and (2) to address age divide and promote inter-generational bonding by proposing new public plaza design in the city of Jiangsu, China. Our hypothesis is that employing carefully selected and curated multi-sensory smart design interventions would minimize the existing conflicts between age groups, foster inter-generational interaction and in such a way improve overall physical, mental and social wellbeing of all age groups. In order to achieve such objectives we simultaneously employed literature review of square dancing, concepts related to inter-generational interaction and sensory design, and the on-site investigations of a public plaza in a housing neighbourhood in Jiangsu, coupled by experimental and conceptual design explorations.

Seeking people that are similar to ourselves is in human nature. However, this may also widen the age gap, especially between the teenagers and the elderly. According to Hagestad and Uhlenberg (2005), age segregation occurs at three dimensions: institutional (e.g., kindergarten vs. senior care centre), spatial (student dormitories vs. nursing homes), and cultural (social media vs. face-to-face interaction). The lack of social relationships between the age groups makes the older adults rather separated from the larger society, which can result in lower knowledge exchange between generations, the loss of empathy and ageism. Ageism is a complex construct, which has three key dimensions, including cognitive (e.g., stereotyping), affective (e.g., prejudicing) and behavioural (e.g., discriminating) dimensions (Marques et al., 2020). Ageism is express either explicitly or implicitly (latently), at individual, community and institutional scales and towards others or towards oneself (Ayalon & Tesch-Romer, 2017; Iversen et al., 2009; Marques et al., 2020; North & Fiske, 2012).

In China, for example, recent societal changes revealed greater gap between the older and the younger generations, which is no longer simply a matter of differences in values and dispositions. China has historically emphasised the respect for the elderly, and many senior adults have an inherent mentality of having a “higher status”, whereby children should learn from older generations. Today's culture is, however, described as a "pre-figurative" one, which demands the reverse – that the older generations should learn from the youth (Gao & Bischoping, 2018). Moreover, many see older adults as having a dominating attitude, while also deploying a badgering interaction style, which is characterized as ill-attuned towards younger people who demand for more egalitarian modes of inter-generational interaction (Gao & Bischoping, 2018). All this led to numerous unfair reports in the media that have portrayed the older generations as backward, corrupt, demanding, and even abusive (e.g., Fauna, 2014), which further vilified the image of the older adults and intensified the conflicts between the elderly and the young.

There is, therefore, a growing need for “the definition or creation of spaces where young, middle-aged, and elderly people from all walks of life can get to know each other enough to build mutual respect, develop cooperative relationships, and reignite the norm of human-heartedness” (Braithwaite, 2002, p. 332). In response, this small design-led study focuses on ‘square dance’, a popular activity among older adults in China, yet recently banned in many cities across China. Our aim is two-fold: (1) to examine ‘square dance’ as an acceptable and healthful activity for older adults; and (2) to address age divide and promote inter-generational bonding by proposing new public plaza design in the city of Jiangsu, China. Our hypothesis is that employing carefully selected and curated multi-sensory smart design interventions would minimize the existing conflicts between age groups, foster inter-generational interaction and in such a way improve overall physical, mental and social wellbeing of all age groups. In order to achieve such objectives we simultaneously employed literature review of square dancing, concepts related to inter-generational interaction and sensory design, and the on-site investigations of a public plaza in a housing neighbourhood in Jiangsu, coupled by experimental and conceptual design explorations.

The 'Square Dance' in China

‘Square dance’ (or guangchangwu in Chinese) is a form of popular physical activity in China, especially among older adults and particularly older women (Zhang & Min, 2019), similar to congregational dancing, encompassing features of line dancing and mass gymnastics (Zhou, 2014). Such an activity typically happens at a neighbourhood square, plaza or park almost every evening or morning (Chao, 2017; Huang, 2016), whereby older adults perform dance or aerobics for fitness, often accompanied by loud and energetic music (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Square Dance in Jiangsu, China (Source: by authors)

The popular square dance has numerous advantages and benefits. Not only does it cost no money, but it can also promote outdoor activities for the elderly, which is good for their physical, mental and social health (Chao, 2017; Keogh et al., 2009). As a moderate intensity physical exercise, it increases the heart rate (Wang et al., 2016), generates light perspiration and reduces body mass index, strengthens muscles and body balance (Sheng-jie & Xian-de, 2013) and contributes positively to prevention against noncommunicable diseases, such as diabetes or osteoporosis (Peng et al., 2020). Research also indicates that square dance, as well as some other social and mental activities, such as playing mahjong, can affect metal wellbeing and cognitive functioning, such as decreasing depressive symtoms, improving memory and attention, and delaying cognitive decline (Alpert, 2011; Bremer, 2007; Chang et al., 2021; Verghese et al., 2003; Zhang & Petrini, 2019). Studies have also shown positive effects of participating in square dancing activity on good mood, attachment to community, strengthening interpersonal relationships, and family cohesion (Li, 2020; Liao et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2020).

However, in recent years, younger generations have developed negative attitudes towards the square dance, primarily due to considerable noise, crowding conditions, competition over the use of public space and other disturbances it often creates (Chao, 2017; Xiaobing et al., 2018; Zhang & Min, 2019; Zhou, 2014). Younger adults rarely, if ever, join this activity, whether actively or passively. Due to social conflicts generated from square dance, many authorities have banned such activities within residential areas or introduced specific measures to regulate the time of activity, spaces used, and the sound volume square dancing (Zhang & Min, 2019). Such an attitude forces older residents to go far away from their homes to places where the activity is still allowed, which is not only unsafe, but also forces them to leave their previously established social circles.

However, in recent years, younger generations have developed negative attitudes towards the square dance, primarily due to considerable noise, crowding conditions, competition over the use of public space and other disturbances it often creates (Chao, 2017; Xiaobing et al., 2018; Zhang & Min, 2019; Zhou, 2014). Younger adults rarely, if ever, join this activity, whether actively or passively. Due to social conflicts generated from square dance, many authorities have banned such activities within residential areas or introduced specific measures to regulate the time of activity, spaces used, and the sound volume square dancing (Zhang & Min, 2019). Such an attitude forces older residents to go far away from their homes to places where the activity is still allowed, which is not only unsafe, but also forces them to leave their previously established social circles.

Inter-generational interaction

The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation (2010) proposed three crucial elements in developing and maintaining stronger attachment of people to their community, namely: an area’s physical beauty, opportunities for socialisation, and a community’s openness to all people (inclusiveness), including “new” comers. Strong people-place relationship is critical for healthful inter-generational encounters (Hammad, 2020). This supports the hypothesis that promoting inter-generational interactions may make a community more attractive and more cohesive, as well as bring wellbeing outcomes to all.

Studies have shown that building a positive attitude towards the aging population can only be achieved through frequent contacts with with unrelated older adults (Funderburk et al., 2006; Jarrott, 2010), which is why relying on family relationships for the creation of inter-generational interactions is not sufficient. Another study by Fingerman and colleagues (2019) reported that older adults interacting with a wider social network (including children and young adults), beyond their established social circles including family members and close friends, tend to be more physically active, and express more positive emotions. On the other hand, studies also suggest the younger people tend to value peripheral ties more than older adults (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). The lack of connection and communication among generations has made both groups less interested in each other, and has a negative impact on both generations. Because young children nowadays interact less and less with neighbours and strangers, Louv (2005) argues that the chances are considerable that they would never be able to learn about community building and self-reliance. This fear of strangers may leave children with an inability to socialize with adults, deepening the divide between generations who never learned to interact with one another. Therefore, creating an activity that that would engage different age groups, may help different generations to build trust and enhance relationships.

The concept of Inter-generational Contact Zones (IGZ) (Kaplan & Sánchez, 2014; Kaplan et al., 2016; Kaplan et al., 2020; Thang, 2015) defines specific places that facilitate meetings, interactions and relationships between older adults and younger generations. Creating an ICZ requires ensuring that the place contains elements and stimuli that trigger responses in all age groups. The TOY (Together Old and Young) programme highlights six dimensions of creating quality intergenerational spaces and initiatives, namely: nourishing relationships and wellbeing; building respect for inclusion and diversity; promoting meaningful interaction with/within community; ensuring mutual exchange and learning; building skills and teamwork; and assessment and monitoring to ensure long-term sustainability (Sánchez et al, 2020, p. 275). It is important to note that inter-generational places do not remove conflict and negotiation, which are important in the process of building mutual understanding and ties (Thang, 2015).

Studies have shown that building a positive attitude towards the aging population can only be achieved through frequent contacts with with unrelated older adults (Funderburk et al., 2006; Jarrott, 2010), which is why relying on family relationships for the creation of inter-generational interactions is not sufficient. Another study by Fingerman and colleagues (2019) reported that older adults interacting with a wider social network (including children and young adults), beyond their established social circles including family members and close friends, tend to be more physically active, and express more positive emotions. On the other hand, studies also suggest the younger people tend to value peripheral ties more than older adults (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). The lack of connection and communication among generations has made both groups less interested in each other, and has a negative impact on both generations. Because young children nowadays interact less and less with neighbours and strangers, Louv (2005) argues that the chances are considerable that they would never be able to learn about community building and self-reliance. This fear of strangers may leave children with an inability to socialize with adults, deepening the divide between generations who never learned to interact with one another. Therefore, creating an activity that that would engage different age groups, may help different generations to build trust and enhance relationships.

The concept of Inter-generational Contact Zones (IGZ) (Kaplan & Sánchez, 2014; Kaplan et al., 2016; Kaplan et al., 2020; Thang, 2015) defines specific places that facilitate meetings, interactions and relationships between older adults and younger generations. Creating an ICZ requires ensuring that the place contains elements and stimuli that trigger responses in all age groups. The TOY (Together Old and Young) programme highlights six dimensions of creating quality intergenerational spaces and initiatives, namely: nourishing relationships and wellbeing; building respect for inclusion and diversity; promoting meaningful interaction with/within community; ensuring mutual exchange and learning; building skills and teamwork; and assessment and monitoring to ensure long-term sustainability (Sánchez et al, 2020, p. 275). It is important to note that inter-generational places do not remove conflict and negotiation, which are important in the process of building mutual understanding and ties (Thang, 2015).

Conceptual Design Explorations

Following the review of relevant theories, models and practices, as well as the site analysis, we embarked on design explorations that involves the transformation of the public plaza in Jiangsu with the aims of tackling two main issues observed: (1) square dance as an acceptable and healthy activity for older adults; and (2) age divide and inter-generational interaction. Our explorations are informed and inspired by sensory design and new technology, which may have the capacity to mitigate age differences and offer new modes of interactions.

In our view, one of the reasons for the disliking of square dancing among younger generations is that it is perceived as a homogenous activity, appropriate only for the older adults, and not attractive enough to younger adults. We have observed a strong contrast in substantially more intense use and occupation of the public plaza at night and its emptiness during the day, with the older adults being the main users. This may also be the result of inadequate and uninviting overall design of the square. Visually, the square dance venue does not offer any eye-catching points. At the same time, the intense audio-stimulation brought by the square dance (music) also forms a barrier between people inside and outside the square, whereby the excessive auditory stimulation triggers negative sensory experience for people who do not participate in square dancing activity.

Cold (2001, p. 17) suggested that “well-being and health may therefore be approached and understood as a dynamic person-role-place-time action and a culturally influenced relationship including sensuous perception, emotional cognition and intellectual consideration moving between the subconscious as well as the conscious field”. We believe that more careful sensory and technological enhancement of the square (that corresponds to both the cultural background of Chinese communities and the contemporary times) could not only attract different user groups at different times of the day, but also promote inter-generational interaction, social cohesion and empathy, that is “a deeper exchange of mutual benefit between 'age groups'” (Reyes, 2016, p. 40), which is different from multigenerational spaces. The proposed conceptual design enhancement involves two scales – micro-scale of urban furniture and the meso-scale of the entire square.

In our view, one of the reasons for the disliking of square dancing among younger generations is that it is perceived as a homogenous activity, appropriate only for the older adults, and not attractive enough to younger adults. We have observed a strong contrast in substantially more intense use and occupation of the public plaza at night and its emptiness during the day, with the older adults being the main users. This may also be the result of inadequate and uninviting overall design of the square. Visually, the square dance venue does not offer any eye-catching points. At the same time, the intense audio-stimulation brought by the square dance (music) also forms a barrier between people inside and outside the square, whereby the excessive auditory stimulation triggers negative sensory experience for people who do not participate in square dancing activity.

Cold (2001, p. 17) suggested that “well-being and health may therefore be approached and understood as a dynamic person-role-place-time action and a culturally influenced relationship including sensuous perception, emotional cognition and intellectual consideration moving between the subconscious as well as the conscious field”. We believe that more careful sensory and technological enhancement of the square (that corresponds to both the cultural background of Chinese communities and the contemporary times) could not only attract different user groups at different times of the day, but also promote inter-generational interaction, social cohesion and empathy, that is “a deeper exchange of mutual benefit between 'age groups'” (Reyes, 2016, p. 40), which is different from multigenerational spaces. The proposed conceptual design enhancement involves two scales – micro-scale of urban furniture and the meso-scale of the entire square.

Micro-scale: Responsive Urban Furniture

At the initial stage, we explored the utilisation of small-scale sensory-driven designs to alleviate the present tension between the older and the younger generations. The aim was first to minimise the noise created by the square dancing so that it can continue to take place in settings close to where older adults live. The lack of sound or sound of low intensity is compensated by other sensory stimuli (visual - moving images and colours, and kinetic - vibrations).

Inter-generational features and programmes should offer opportunities for and encourage meaningful communication between different age groups. Most communication at the square among the strangers spontaneously occurs almost exclusively among the peers of either older adults or younger generations. Once the main conflict (noise) is removed, more meaningful communication among different generations may occur, potentially leading to greater mutual respect, empathy and exchange.

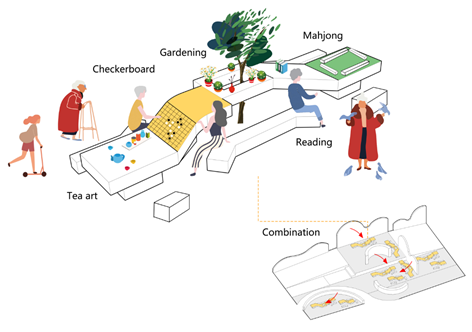

Accordingly, our initial design proposed a piece of multifunctional furniture - a set of tables and benches with interactive features to prompt curiosity and interaction both with the features and with other users of the square (Figure 2). This was done by adding various activity surfaces to the table, such as checkboard, mahjong, other board games and gardening (note that all surfaces are flat, although the drawing creates an illusion of slanted surfaces). Moreover, furniture is also equipped with gravity sensing and infrared devices to sense the number of users and when the features are in use. For example, when someone occupies a seat, the embedded gravity sensors will trigger the fountain (with music) so that children can play with water. To activate the fountain, children hence need to ask others to sit on the bench and initiate communication. In this way, the design can provide another opportunity for children and the elderly to spend time with each other and promote inter-generational interaction.

Inter-generational features and programmes should offer opportunities for and encourage meaningful communication between different age groups. Most communication at the square among the strangers spontaneously occurs almost exclusively among the peers of either older adults or younger generations. Once the main conflict (noise) is removed, more meaningful communication among different generations may occur, potentially leading to greater mutual respect, empathy and exchange.

Accordingly, our initial design proposed a piece of multifunctional furniture - a set of tables and benches with interactive features to prompt curiosity and interaction both with the features and with other users of the square (Figure 2). This was done by adding various activity surfaces to the table, such as checkboard, mahjong, other board games and gardening (note that all surfaces are flat, although the drawing creates an illusion of slanted surfaces). Moreover, furniture is also equipped with gravity sensing and infrared devices to sense the number of users and when the features are in use. For example, when someone occupies a seat, the embedded gravity sensors will trigger the fountain (with music) so that children can play with water. To activate the fountain, children hence need to ask others to sit on the bench and initiate communication. In this way, the design can provide another opportunity for children and the elderly to spend time with each other and promote inter-generational interaction.

Figure 2 - Conceptual design of multi-functional and responsive furniture – micro-scale (Source: by authors)

While this segment of design does not address square dancing activity, it is supplementary to it, allowing different activities to happen simultaneously and at different times of the day. This is in line with William H. White’s (1980) call for triangulation of public space features and programmes to increase the diversity of things to do in a place, and thus intensity of its use, and encouraging social encounters. It should be noted that this conceptual design needs further refinement in order to account for greater ergonomic comfort and flexibility. For instance, benches should also provide proper backrests and armrests to not only improve comfort and promote dwelling in place, but also to ease their use by the older adults. Moreover, chess- and mahjong- playing typically attracts groups of people, and requires more seats as well as more flexible arrangements. Finally, some sort of a shelter would provide greater use of space during different weather conditions, such as rain, snow or strong sun.

Meso-scale: Responsive Ambience

Thibaud (2011) argued that some types of ambiance are designed to plunge us into a state of tension and excitement that makes it almost impossible not to react, while other types of ambiance tend to calm us down and are more conducive to contemplation and thought. “An ambiance may increase or reduce our capacity for action by placing us in a particular physical and emotional state” (Thibaud, 2011, p. 209).

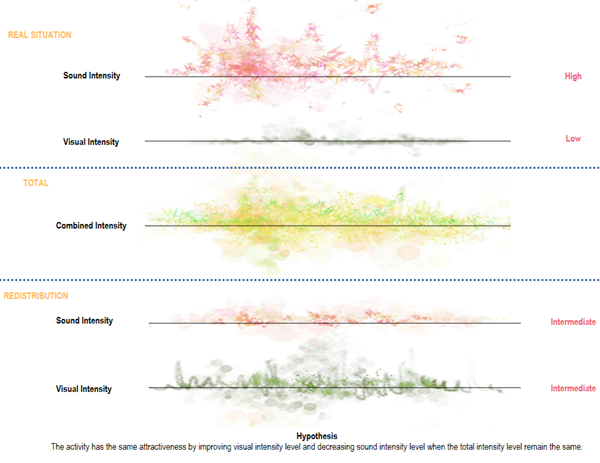

With this in mind, our further design exploration focuses on the redistribution and reconnection of sensory experiences (Figure 3) through smart visual, sound and vibration technologies in order to create an immersive and intuitive ambience, and provide opportunities for inter-generational dialogue and interaction in a joyful, meaningful and mutually respectful manner. In such a way, we aim to improve the perception of square dance and make it more acceptable and attractive activity to younger generations, especially young children and teenagers. To achieve this, we look at improving the public space quality as a whole, with the urban furniture and smart technology (e.g., responsive tables, benches, pavement and video screens) being the main design drivers. While at the very least, the design should allow different age groups to perform their activities simultaneously in the same space without causing major conflicts, we see the capacity of the proposed design features to also engage different generations in shared activities.

With this in mind, our further design exploration focuses on the redistribution and reconnection of sensory experiences (Figure 3) through smart visual, sound and vibration technologies in order to create an immersive and intuitive ambience, and provide opportunities for inter-generational dialogue and interaction in a joyful, meaningful and mutually respectful manner. In such a way, we aim to improve the perception of square dance and make it more acceptable and attractive activity to younger generations, especially young children and teenagers. To achieve this, we look at improving the public space quality as a whole, with the urban furniture and smart technology (e.g., responsive tables, benches, pavement and video screens) being the main design drivers. While at the very least, the design should allow different age groups to perform their activities simultaneously in the same space without causing major conflicts, we see the capacity of the proposed design features to also engage different generations in shared activities.

Figure 3 - Proposed sensory redistribution (Source: by authors)

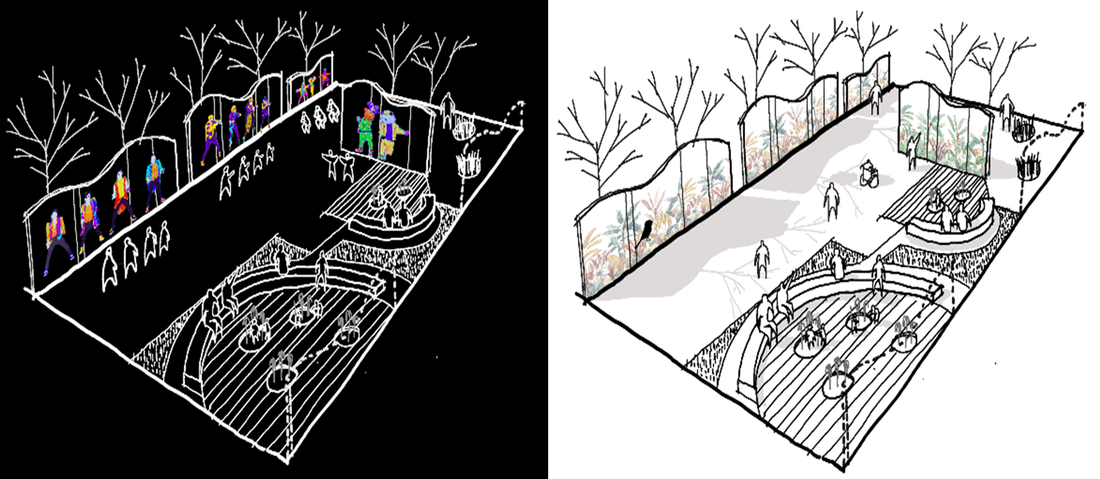

Changing the sensory ambience of a square (Figure 3) entails lowering the sound intensity level and improving the visual and aesthetic quality of the plaza, coupled with tactile and kinetic engagement. In order to achieve this and thus allow older adults to continue square dancing in the plaza, while reducing the conflicts with the neighbours, we introduce a series of ‘wonderwall’ (Figure 4) visual device features, comprising LED screens, and equipped with movement detectors. This is supported by the recent study by Yu and colleagues (2020), who successfully employed somatosensory square dance system based on Laban Movement analysis as means for fitness and dance training to improve older Chinese adults’ health conditions, while also moderating noise and space related conflicts. By this ‘wonderwall’ feature, we attempted to replace part of the auditory stimulation with immersive, intuitive, interactive and movement tracking smart visual and tactile stimulation. We further enhanced the visual stimulus in the plaza by generating virtual characters on LED screens, equipped with movement detectors, which are used to imitate and reflect the dancing movements of the elderly standing in front of the screens. Other studies have also employed various types of VR-based exergames to address older adults’ mental health (e.g., Li et al., 2020; Tobiasson et al., 2015; Unbehaun et al., 2020). Xu and colleagues (2016) reported that engagement in such games significantly decreased social anxiousness as well as increased sociability among young-old adults (age 60-74) who played with younger adults, and among old-old adults (above 75 of age) who played with their peers. In addition, we added vibrating technology to the square surface (pavement) to transform the sound rhythm into kinetic sensory stimulus by transmitting and implying the rhythm of the music. In such way, music with a lower volume (or even no sound) can be played, without compromising dancing activity and conflicting other activities in plaza.

Figure 4 - Conceptual design of the ‘Wonderwall’ – meso-scale (Source: by authors)

We hope that ideas presented in this conceptual design could not only effectively reduce the noise generated by the square dancing, but also enrich inter-generational interaction through novel technological means. Intuitive smart technology can be a powerful and joyful means of knowledge exchange and skill building for all age groups. This may attract younger age groups, who may want to use the plaza for individual and team activities, such as breakdancing, gaming or sports activities, for instance. The space, however, does not only offer customised and simultaneous use by different generations or the use at different times of the day. It also provides opportunities for different age groups to engage in same activities, such as different types of dance activities, or exercises, beyond passive collocation. We hope that, in such a way, our design would support neighbours in progressing along what Grannis (2009) calls stages of “neighbouring”, from passive presence and acknowledgment of others, to intentional engagement, shared experience and building mutual trust, empathy and friendship.

Further refinements may be needed to form greater synergies between the two segments of design proposal, in reference to spatial arrangement, visibility and greater comfort.

Further refinements may be needed to form greater synergies between the two segments of design proposal, in reference to spatial arrangement, visibility and greater comfort.

Conclusion

“When 'active aging' is embraced, life expectancy can be extended, and individuals have the opportunity to experience social, physical, and mental well-being while remaining connected with their community” (Fitzgerald & Caro, 2014, p. 3).

As designers, we should try our best to create such opportunities for all ages in a holistic and integrated manner. While older adults may have different needs, interests and challenges than other age groups, and sometimes even conflicting ones, it is important not to create designs that only meet their needs, as this would further widen the gap between generations and nourish ageism. Enhancing inter-generational interaction requires designers to make conscious and sensitive efforts and explore alternative ways towards healthy and empathetic built environments.

There are many aspects that have not been taken into consideration in the preliminary designs proposed in this short article. They are only conceptual diagrammatic propositions, and to a considerable extent naïve, but also genuine attempts. Further design explorations are needed to improve the design of urban furniture and overall public plaza considering comfort, ergonomics, and arrangement to support activity better and encourage both peer-to-peer and inter-generational social interaction.

There are many aspects that have not been taken into consideration in the preliminary designs proposed in this short article. They are only conceptual diagrammatic propositions, and to a considerable extent naïve, but also genuine attempts. Further design explorations are needed to improve the design of urban furniture and overall public plaza considering comfort, ergonomics, and arrangement to support activity better and encourage both peer-to-peer and inter-generational social interaction.

Acknowledgements

The content presented in this article was produced during the course “City and Senses: Multi-sensory Approach to Urbanism” taught in AY2020/21 by Dr Zdravko Trivic at the Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore. Special thanks to Dr Simone Shu-Yeng Chung and her studio members and Dr Ruzica Bozovic-Stamenovic from NUS for providing valuable feedback through a workshop and a guest lecture.

About the Authors

|

Yunhua Zhu, Bachelor of Architecture and MA of Urban Design, is a graduate at the Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore. Her research interests include: urban space in high-density metropolises, inclusive placemaking, city renovation, and multi-sensorial urbanism.

|

|

Zdravko Trivic, PhD is Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore. His research interests include: multi-sensorial urbanism, health-supportive and ageing-friendly neighbourhood design, urban space in high-density contexts, creative placemaking and community participation.

|

References

Alpert, P. T. (2011). The health benefits of dance. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 23(2),155–157. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1084822310384689

Ayalon, L., & Tesch-Romer, C. (2017). Taking a closer look at ageism: Self-and other-directed ageist attitudes and discrimination. European Journal of Aging, 14, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0409-9

Braithwaite, V. (2002). Reducing Ageism. In T.D. Nelson (Ed.), Ageism: Stereotyping and Prejudice Against Older Persons (pp. 311–337). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bremer, Z. (2007). Dance as a form of exercise. British Journal of General Practice, 57(535), 166. PMCID: PMC2034191

Chang, J., Zhu, W., Zhang, J., Yong, L., Yang, M., Wang, J., & Yan, J. (2021). The effect of Chinese square dance exercise on cognitive function in older women with mild cognitive impairment: The mediating effect of mood status and quality of life. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 711079. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.711079

Chao, M. (2017). Reading movement in the everyday: The rise of Guangchangwu in a Chinese village. International Journal of Communication, 11, 4499–4522. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5607/2178

Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448

Cold, B. (2001). Aesthetics, well-being, and health. In B. Cold (Ed.), Aesthetics, Well-being, and Health (pp. 11–23). Aldershot; Burlington: Ashgate.

Dutton, J. (2015). The surprising world of synaesthesia. The Psychologist, 28, 106–109. Retrieved May 13, 2021, from https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-28/february-2015/surprising-world-synaesthesia

Fauna. (2014). Old man slaps youth for not giving up seat, then suddenly dies. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from http://www.chinasmack.com/2014/stories/old-man-slaps-youth-for-not-giving-up-seat-then-suddenly-dies.html

Fingerman, K. L., Huo, M., Charles, S. T., & Umberson, D. J. (2020). Variety is the spice of late life: Social integration and daily activity. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(2), 377–388. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1093/geronb/gbz007

Fitzgerald, K.G., & Caro, F.G. (2014). An overview of age-friendly cities and communities around the world. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 26(1-2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2014.860786

Funderburk, B., Damron-Rodriguez, J., Storms, L. L., & Solomon, D. (2006). Endurance of undergraduate attitudes toward older adults. Educational Gerontology, 32(6), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270600685651.

Gao, Z., & Bischoping, K. (2018). The emergence of an elder-blaming discourse in twenty-first century China. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 33(2), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-018-9347-7

Grannis, R. (2009). From the ground up: Translating geography into community through neighbouring. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hagestad, G. O., & Uhlenberg, P. (2005). The social separation of old and young: A root of ageism. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 343–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00409.x

Hammad, S. H. (2020). Intergenerational contact zones in contested places and spaces: the olive tree as entity and symbol. In M. Kaplan, L. L. Thang, M. Sánchez, & J. Hoffman (Eds.), Intergenerational Contact Zones: Place-based Strategies for Promoting Social Inclusion and Belonging (pp. 245-256). New York: Routledge.

Iversen, T. N., Larsen, L., & Solem, P. E. (2009). A conceptual analysis of ageism. Nordic Psychology, 61(3), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1027/1901-2276.61.3.4

Jarrott, S. E. (2010). Programs that affect intergenerational solidarity. In M. A. Cruz-Saco, & S. Zelenev (Eds.), Intergenerational Solidarity (pp. 113–127). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. (2010). Knight soul of the community 2010 - Why people love where they live and why it matters: A national perspective. Miami: John S. and James L. Knight Foundation & Gallup. Retrieved from https://www.issuelab.org/resources/10006/10006.pdf

Kaplan, M., & Sánchez, M. (2014). Intergenerational programmes. In S. Harper, & K. Hamblin (Eds.), International handbook on ageing and public policy (pp. 367–383). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Kaplan, M., Thang, L. L., Sánchez, M., & Hoffman, J., (Eds.). (2016). Intergenerational contact zones – A compendium of applications. University Park: Penn State Extension. Retrieved from https://aese.psu.edu/extension/intergenerational/articles/intergenerational-contact-zones

Kaplan, M., Thang, L. L., Sánchez, M., & Hoffman, J. (2020). Introduction. In M. Kaplan, L. L. Thang, M. Sánchez, & J. Hoffman (Eds.), Intergenerational Contact Zones: Place-based Strategies for Promoting Social Inclusion and Belonging (pp. 1–13). New York: Routledge.

Keogh, J. W., Kilding, A., Pidgeon, P., Ashley, L., & Gillis, D. (2009). Physical benefits of

dancing for healthy older adults: A review. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 17(4), 479–500. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.17.4.479

Li, X. (2020). The thought on square dancing heat in China. Frontiers in Art Research, 2(2). doi: 10.25236/FAR.2020.020208

Li, J., Theng, Y.-L., & Foo, S. (2020). Play mode effect of exergames on subthreshold depression older adults: A randomized pilot trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 552416. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.552416

Liao, J., Chen, S., Chen, S., & Yang, Y. (2019). Personal and social environmental correlates of square dancing habits in Chinese middle-aged and older adults living in communities. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 27(5), 696–702. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2018-0310

Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

Marques, S., Mariano, J., Mendonça, J., De Tavernier, W., Hess, M., Naegele, L., Peixeiro, F., & Martins, D. (2020). Determinants of ageism against older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072560

North, M. S., & Fiske, S. T. (2012). An inconvenienced youth? Ageism and its potential intergenerational roots. Psychological bulletin, 138(5), 982–997. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027843

OECD, & WHO (2020), "Ageing", in Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2020: Measuring Progress Towards Universal Health Coverage. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1ad1c42a-en

Peng, F., Yan, H., Sharma, M., Liu, Y., Lu, Y., Zhu, S., Li, P., Ren, N., Li, T., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Exploring factors influencing whether residents participate in square dancing using social cognitive theory: A cross-sectional survey in Chongqing, China. Medicine, 99(4), e18685. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000018685

Reyes, S. (2016). Intergenerational interactions: Designing for the young & old. Masters of Landscape Architecture Thesis. University of Florida. Retrieved on May 13, 2021, from https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00007999/00001

Sánchez, M., Díaz, M. P., Rodríguez, A., & Pallarés, R. B. (2020). Intergenerational programs and Intergenerational Contact Zones: aligning notions of “good quality”. In M. Kaplan, L. L. Thang, M. Sánchez, & J. Hoffman (Eds.), Intergenerational Contact Zones: Place-based Strategies for Promoting Social Inclusion and Belonging (pp. 274-285). New York: Routledge.

Thang, L. L. (2015). Creating an intergenerational contact zone: Encounters in public spaces within Singapore’s public housing neighborhoods. In R. Vanderbeck, & N. Worth (Eds.), Intergenerational spaces (pp. 17–32). London: Routledge. doi:10.1080/15350770.2016.1229535

Thibaud, J-P. (2011). The sensory fabric of urban ambiances. The Senses and Society, 6(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.2752/174589311X12961584845846

Tobiasson, H., Sundblad, Y., Walldius, Å., & Hedman, A. (2015). Designing for active life: Moving and being moved together with dementia patients. International Journal of Design, 9(3), 47-62. http://www.ijdesign.org/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/1886/713

Unbehaun, D., Taugerbeck, S., Aal, K., Vaziri, D. D., Lehmann, J., Tolmie, P., Wieching, R., & Wulf, V. (2020). Notes of memories: Fostering social interaction, activity and reminiscence through an interactive music exergame developed for people with dementia and their caregivers. Human–Computer Interaction. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2020.1746910

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019, Volume II: Demographic Profiles (ST/ESA/SER.A/427). Retrieved from https://population.un.org/wpp/Graphs/1_Demographic%20Profiles/China.pdf

Verghese, J., Lipton, R. B., Katz, M. J., Hall, C. B., Derby, C. A., Kuslansky, G., Ambrose, A. F., Sliwinski, M., & Buschke, H. (2003). Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. The New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 2508–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022252

Wang, S.-S., Lay, S., Yu, H.-N., & Shen, S-R. (2016). Dietary guidelines for Chinese residents (2016): comments and comparisons. Journal of Zhejiang University - Science B, 17, 649–56.

https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1600341

Whyte, W. H. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Washington: Conservation Foundation.

Xiaobing, L., Xiaolong, Z., & Bo, Z. (2018). Thinking about the contradictions of space use of square dance in Chinese cold cities through newspaper reports. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 371. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/371/1/012040.

Xie, W., Chen, W.-W.. & Zhang, L. (2020). The effect of square dance on family cohesion and subjective well-being of middle-aged and empty-nest women in China. Health Care for Women International, 42(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2020.1797041

Xu, X., Li, J., Pham, T. P., Salmon, C. T., & Theng, Y. L. (2016). Improving psychosocial well-being of older adults through exergaming: The moderation effects of intergenerational communication and age cohorts. Games for Health Journal, 5(6), 389-397. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2016.0060

Yu, C., Rau, P. P., & Liu, X. (2020). Development and preliminary usability evaluation of a somatosensory square dance system for older Chinese persons: Mixed methods study. JMIR Serious Games, 8(2), e16000.

doi: 10.2196/16000. PMID: 32463376; PMCID: PMC7290448.

Zhang, Q., & Min, G. (2019). Square dancing: A multimodal analysis of the discourse in the People’s Daily. Chinese Language and Discourse, 10(1), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1075/cld.18011.zha

Zhou, L. (2014). Music is not our enemy, but noise should be regulated: Thoughts on shooting/conflicts related to dama square dance in china. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(3), 279–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.935153

Ayalon, L., & Tesch-Romer, C. (2017). Taking a closer look at ageism: Self-and other-directed ageist attitudes and discrimination. European Journal of Aging, 14, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0409-9

Braithwaite, V. (2002). Reducing Ageism. In T.D. Nelson (Ed.), Ageism: Stereotyping and Prejudice Against Older Persons (pp. 311–337). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bremer, Z. (2007). Dance as a form of exercise. British Journal of General Practice, 57(535), 166. PMCID: PMC2034191

Chang, J., Zhu, W., Zhang, J., Yong, L., Yang, M., Wang, J., & Yan, J. (2021). The effect of Chinese square dance exercise on cognitive function in older women with mild cognitive impairment: The mediating effect of mood status and quality of life. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 711079. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.711079

Chao, M. (2017). Reading movement in the everyday: The rise of Guangchangwu in a Chinese village. International Journal of Communication, 11, 4499–4522. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5607/2178

Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448

Cold, B. (2001). Aesthetics, well-being, and health. In B. Cold (Ed.), Aesthetics, Well-being, and Health (pp. 11–23). Aldershot; Burlington: Ashgate.

Dutton, J. (2015). The surprising world of synaesthesia. The Psychologist, 28, 106–109. Retrieved May 13, 2021, from https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-28/february-2015/surprising-world-synaesthesia

Fauna. (2014). Old man slaps youth for not giving up seat, then suddenly dies. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from http://www.chinasmack.com/2014/stories/old-man-slaps-youth-for-not-giving-up-seat-then-suddenly-dies.html

Fingerman, K. L., Huo, M., Charles, S. T., & Umberson, D. J. (2020). Variety is the spice of late life: Social integration and daily activity. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(2), 377–388. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1093/geronb/gbz007

Fitzgerald, K.G., & Caro, F.G. (2014). An overview of age-friendly cities and communities around the world. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 26(1-2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2014.860786

Funderburk, B., Damron-Rodriguez, J., Storms, L. L., & Solomon, D. (2006). Endurance of undergraduate attitudes toward older adults. Educational Gerontology, 32(6), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270600685651.

Gao, Z., & Bischoping, K. (2018). The emergence of an elder-blaming discourse in twenty-first century China. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 33(2), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-018-9347-7

Grannis, R. (2009). From the ground up: Translating geography into community through neighbouring. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hagestad, G. O., & Uhlenberg, P. (2005). The social separation of old and young: A root of ageism. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 343–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00409.x

Hammad, S. H. (2020). Intergenerational contact zones in contested places and spaces: the olive tree as entity and symbol. In M. Kaplan, L. L. Thang, M. Sánchez, & J. Hoffman (Eds.), Intergenerational Contact Zones: Place-based Strategies for Promoting Social Inclusion and Belonging (pp. 245-256). New York: Routledge.

Iversen, T. N., Larsen, L., & Solem, P. E. (2009). A conceptual analysis of ageism. Nordic Psychology, 61(3), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1027/1901-2276.61.3.4

Jarrott, S. E. (2010). Programs that affect intergenerational solidarity. In M. A. Cruz-Saco, & S. Zelenev (Eds.), Intergenerational Solidarity (pp. 113–127). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. (2010). Knight soul of the community 2010 - Why people love where they live and why it matters: A national perspective. Miami: John S. and James L. Knight Foundation & Gallup. Retrieved from https://www.issuelab.org/resources/10006/10006.pdf

Kaplan, M., & Sánchez, M. (2014). Intergenerational programmes. In S. Harper, & K. Hamblin (Eds.), International handbook on ageing and public policy (pp. 367–383). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Kaplan, M., Thang, L. L., Sánchez, M., & Hoffman, J., (Eds.). (2016). Intergenerational contact zones – A compendium of applications. University Park: Penn State Extension. Retrieved from https://aese.psu.edu/extension/intergenerational/articles/intergenerational-contact-zones

Kaplan, M., Thang, L. L., Sánchez, M., & Hoffman, J. (2020). Introduction. In M. Kaplan, L. L. Thang, M. Sánchez, & J. Hoffman (Eds.), Intergenerational Contact Zones: Place-based Strategies for Promoting Social Inclusion and Belonging (pp. 1–13). New York: Routledge.

Keogh, J. W., Kilding, A., Pidgeon, P., Ashley, L., & Gillis, D. (2009). Physical benefits of

dancing for healthy older adults: A review. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 17(4), 479–500. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.17.4.479

Li, X. (2020). The thought on square dancing heat in China. Frontiers in Art Research, 2(2). doi: 10.25236/FAR.2020.020208

Li, J., Theng, Y.-L., & Foo, S. (2020). Play mode effect of exergames on subthreshold depression older adults: A randomized pilot trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 552416. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.552416

Liao, J., Chen, S., Chen, S., & Yang, Y. (2019). Personal and social environmental correlates of square dancing habits in Chinese middle-aged and older adults living in communities. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 27(5), 696–702. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2018-0310

Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

Marques, S., Mariano, J., Mendonça, J., De Tavernier, W., Hess, M., Naegele, L., Peixeiro, F., & Martins, D. (2020). Determinants of ageism against older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072560

North, M. S., & Fiske, S. T. (2012). An inconvenienced youth? Ageism and its potential intergenerational roots. Psychological bulletin, 138(5), 982–997. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027843

OECD, & WHO (2020), "Ageing", in Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2020: Measuring Progress Towards Universal Health Coverage. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1ad1c42a-en

Peng, F., Yan, H., Sharma, M., Liu, Y., Lu, Y., Zhu, S., Li, P., Ren, N., Li, T., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Exploring factors influencing whether residents participate in square dancing using social cognitive theory: A cross-sectional survey in Chongqing, China. Medicine, 99(4), e18685. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000018685

Reyes, S. (2016). Intergenerational interactions: Designing for the young & old. Masters of Landscape Architecture Thesis. University of Florida. Retrieved on May 13, 2021, from https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00007999/00001

Sánchez, M., Díaz, M. P., Rodríguez, A., & Pallarés, R. B. (2020). Intergenerational programs and Intergenerational Contact Zones: aligning notions of “good quality”. In M. Kaplan, L. L. Thang, M. Sánchez, & J. Hoffman (Eds.), Intergenerational Contact Zones: Place-based Strategies for Promoting Social Inclusion and Belonging (pp. 274-285). New York: Routledge.

Thang, L. L. (2015). Creating an intergenerational contact zone: Encounters in public spaces within Singapore’s public housing neighborhoods. In R. Vanderbeck, & N. Worth (Eds.), Intergenerational spaces (pp. 17–32). London: Routledge. doi:10.1080/15350770.2016.1229535

Thibaud, J-P. (2011). The sensory fabric of urban ambiances. The Senses and Society, 6(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.2752/174589311X12961584845846

Tobiasson, H., Sundblad, Y., Walldius, Å., & Hedman, A. (2015). Designing for active life: Moving and being moved together with dementia patients. International Journal of Design, 9(3), 47-62. http://www.ijdesign.org/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/1886/713

Unbehaun, D., Taugerbeck, S., Aal, K., Vaziri, D. D., Lehmann, J., Tolmie, P., Wieching, R., & Wulf, V. (2020). Notes of memories: Fostering social interaction, activity and reminiscence through an interactive music exergame developed for people with dementia and their caregivers. Human–Computer Interaction. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2020.1746910

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019, Volume II: Demographic Profiles (ST/ESA/SER.A/427). Retrieved from https://population.un.org/wpp/Graphs/1_Demographic%20Profiles/China.pdf

Verghese, J., Lipton, R. B., Katz, M. J., Hall, C. B., Derby, C. A., Kuslansky, G., Ambrose, A. F., Sliwinski, M., & Buschke, H. (2003). Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. The New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 2508–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022252

Wang, S.-S., Lay, S., Yu, H.-N., & Shen, S-R. (2016). Dietary guidelines for Chinese residents (2016): comments and comparisons. Journal of Zhejiang University - Science B, 17, 649–56.

https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1600341

Whyte, W. H. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Washington: Conservation Foundation.

Xiaobing, L., Xiaolong, Z., & Bo, Z. (2018). Thinking about the contradictions of space use of square dance in Chinese cold cities through newspaper reports. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 371. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/371/1/012040.

Xie, W., Chen, W.-W.. & Zhang, L. (2020). The effect of square dance on family cohesion and subjective well-being of middle-aged and empty-nest women in China. Health Care for Women International, 42(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2020.1797041

Xu, X., Li, J., Pham, T. P., Salmon, C. T., & Theng, Y. L. (2016). Improving psychosocial well-being of older adults through exergaming: The moderation effects of intergenerational communication and age cohorts. Games for Health Journal, 5(6), 389-397. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2016.0060

Yu, C., Rau, P. P., & Liu, X. (2020). Development and preliminary usability evaluation of a somatosensory square dance system for older Chinese persons: Mixed methods study. JMIR Serious Games, 8(2), e16000.

doi: 10.2196/16000. PMID: 32463376; PMCID: PMC7290448.

Zhang, Q., & Min, G. (2019). Square dancing: A multimodal analysis of the discourse in the People’s Daily. Chinese Language and Discourse, 10(1), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1075/cld.18011.zha

Zhou, L. (2014). Music is not our enemy, but noise should be regulated: Thoughts on shooting/conflicts related to dama square dance in china. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(3), 279–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.935153