Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2021:7;12

BOOK REVIEW

Restorative Cities: Urban Design for Mental Health and Wellbeing by Jenny Roe and Layla McCay -

a book review

Jenny Roe & Layla McCay, London: Bloomsbury, 2021

ISBN Paperback: 9781350112889; Hardback: 9781350112872; E-book (Epub & Mobi): 9781350112896; E-book (PDF): 9781350112902

ISBN Paperback: 9781350112889; Hardback: 9781350112872; E-book (Epub & Mobi): 9781350112896; E-book (PDF): 9781350112902

Hannah Grove

Department of Geography, Maynooth University, Ireland

Department of Geography, Maynooth University, Ireland

Citation: Grove H (2021). Restorative Cities: Urban Design for Mental Health and Wellbeing by Jenny Roe and Layla McCay. - a book review. Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 7;12

Restorative Cities is a welcome, timely and important addition to the existing healthy urban planning literature. The main contribution of this book is its comprehensive and clear framework to guide practitioners, researchers and citizens to think through the mental health impacts of the built environment, as well as offering practical solutions and ideas to design more restorative and resilient cities for all.

The book begins with a compelling case for why such an approach is needed, providing an overview of increasing urbanisation coinciding with increased rates of stress, depression and mental illness. Roe & McCay examine previous urban responses to these challenges and argue for a “quieter” [p.2] and refreshing approach, that of restorative urbanism. This approach builds on existing work on the topics of healthy cities, restorative environments, liveable cities, age, and child friendly environments. It draws on and clearly explains well-known restorative environment and health-promoting theories and provides useful definitions on different aspects of mental health. The authors emphasise the need for a systems approach to mental health, recognising the complexity of factors that influence mental health, of which the environment is a vital (and often overlooked) component.

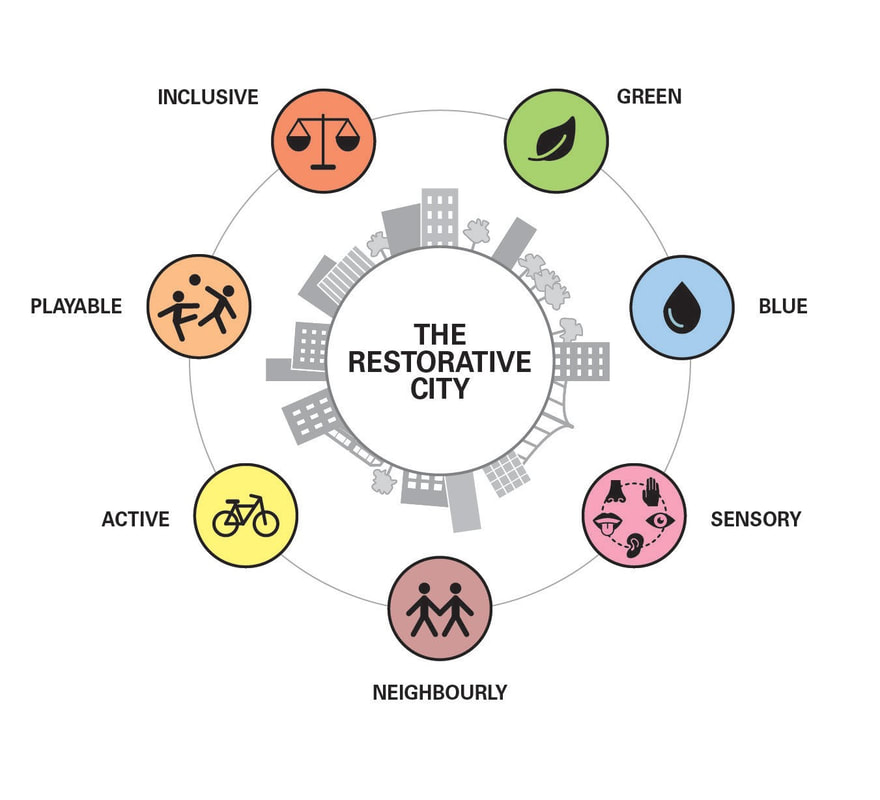

There is a clear structure throughout. Chapter 1 introduces the overall framework of the restorative city, while each chapter then focuses on one of the seven strands of the restorative cities’ framework. For those familiar with the Mind the GAPS Framework, which had four components (Green Places, Active Places, Pro-Social Places and Safe Places) [1], the Restorative City builds on this work with some welcome additions. For example, the new framework emphasises the importance of not just the Green City (Chapter 2) but also the Blue City (Chapter 3), which was missing from the original framework. There is a new category labelled the Sensory City (Chapter 4), incorporating the five senses and overall atmosphere of a place and how this influences mental health. The Neighbourly City (Chapter 5) was formerly the Pro-Social places in the Mind the GAPS framework and the Active City remains the same (Chapter 6). There are then two additional categories: the Playable City (Chapter 7), focusing on opportunities for play for all ages, and finally, the Inclusive City (Chapter 7), which highlights ways to ensure that all population groups are included within this process. Meanwhile, elements of the Safe Places category from the original framework are incorporated throughout each of the pillars, particularly within the Neighbourly City, Inclusive and Green City chapters.

The book begins with a compelling case for why such an approach is needed, providing an overview of increasing urbanisation coinciding with increased rates of stress, depression and mental illness. Roe & McCay examine previous urban responses to these challenges and argue for a “quieter” [p.2] and refreshing approach, that of restorative urbanism. This approach builds on existing work on the topics of healthy cities, restorative environments, liveable cities, age, and child friendly environments. It draws on and clearly explains well-known restorative environment and health-promoting theories and provides useful definitions on different aspects of mental health. The authors emphasise the need for a systems approach to mental health, recognising the complexity of factors that influence mental health, of which the environment is a vital (and often overlooked) component.

There is a clear structure throughout. Chapter 1 introduces the overall framework of the restorative city, while each chapter then focuses on one of the seven strands of the restorative cities’ framework. For those familiar with the Mind the GAPS Framework, which had four components (Green Places, Active Places, Pro-Social Places and Safe Places) [1], the Restorative City builds on this work with some welcome additions. For example, the new framework emphasises the importance of not just the Green City (Chapter 2) but also the Blue City (Chapter 3), which was missing from the original framework. There is a new category labelled the Sensory City (Chapter 4), incorporating the five senses and overall atmosphere of a place and how this influences mental health. The Neighbourly City (Chapter 5) was formerly the Pro-Social places in the Mind the GAPS framework and the Active City remains the same (Chapter 6). There are then two additional categories: the Playable City (Chapter 7), focusing on opportunities for play for all ages, and finally, the Inclusive City (Chapter 7), which highlights ways to ensure that all population groups are included within this process. Meanwhile, elements of the Safe Places category from the original framework are incorporated throughout each of the pillars, particularly within the Neighbourly City, Inclusive and Green City chapters.

Figure 1: Restorative City Framework. Source: Restorative Cities: Urban Design for Mental Health and Wellbeing by Jenny Roe and Layla McCay, Bloomsbury Publishing (2021).

Each chapter begins with a ‘highlights’ section and defines key concepts of relevance. An overview of the dominant theories for each strand is then presented, with useful diagrams demonstrating the established pathways that the environment can directly and indirectly influence mental health and flourishing, as well as the modifiers that influence the extent of this effect. An overview of the empirical evidence to date is then summarised in clear sub-headings, focusing on what is known about the benefits to mental health and wellbeing. This examination of the literature has a particular focus on systematic reviews where available, making this an excellent starting point to then explore further research on each topic. Each chapter concludes with real world examples for inspiration and suggest design guidelines to follow at both the neighbourhood and city scale, accompanied with illustrative diagrams.

For those who are familiar with this literature and already bridging health and planning disciplines, many of the individual components of this book will be familiar, particularly those pillars that are more established. However, one of the strengths of this book is the way that different components of restorative urbanism have been brought together through the framework in a very clear way. In this way, the restorative cities framework is far greater than the sum of its individual parts. Roe & McCay provide a comprehensive overview of the key ways that the built environment can influence mental health. They capture and present complex ideas and theories and bring them together in an accessible form. This means that for those who are new to literature that connects mental health and urban design, this book will be very easy to follow.

This book will be useful for those who are interested in incorporating mental health into planning and want to do more but are not sure where to start. The restorative cities framework and the guidance provided could be useful for students, lecturers, practitioners and researchers alike and could be applied in many different ways. I have envisioned several applications for this framework based on my own experience within planning policy, as a PhD student conducting research on ageing well in place and as a tutor on the topic of Healthy Local Environments. In terms of planning practice, I could see this framework being used to produce audits within cities to determine how restorative they already are, to identify the existing strengths within a city, as well as identify ways in which they could be improved. This could be carried out within local authorities or as part of assignments within modules. I have previously set assignments asking students to conduct ‘health checks’ of their local environments within a Healthy Local Environment module and this framework would be a useful addition to guide this work.

The book emphasises that restorative urbanism “can build incrementally, but it is important that the overarching masterplan be established” [p.197]. Here, the authors have recognised the important role in the power of small or softer interventions in transforming cities that can build cumulatively over time. One way of incorporating this work strategically is by emphasising the importance of mental health within Local Plans or Development Plan Documents (DPDs), or potentially developing Mental Health Supplementary Planning Documents (SPDs) to provide the policy structure to guide development management. In the past, planning policy has been criticised for ‘tokenistic’ references to health [2], but this framework could be applied to implement restorative urbanism more comprehensively within policy. To transparently demonstrate progress and to ensure that progress is in the right direction, local authorities could provide updates through their Annual Monitoring Reports on the different pillars, to demonstrate the ways that they have been implementing these guidelines. Furthermore, existing strategies and future developments could be evaluated through Mental Health Impact Assessments. Whilst there are guides already available for Heath Impact Assessments [3], future work might consider what additional components would be needed to incorporate this broader framework.

A key theme throughout this book is the emphasis on the need for participatory approaches, recognising that “the community is expert in what it needs and designing an inclusive place is a group effort” [p.106]. Such an approach calls for and raises the importance of participatory and community-based planning. I agree with Roe & McCay that it is important to move away from more reactive responses to planning and instead to encourage communities to get involved and demand the cities that they would like to see. For those groups who are more disengaged and disempowered from the planning process, additional efforts will be required to ensure that their perspectives are heard.

A strength of this framework is the recognition of the subjective experiences of place. To understand the different experiences and needs of diverse population groups, requires ‘alternative’ research designs and methodologies that are more qualitative, creative, spatial and participatory [4]. These are increasingly being applied within health geography: for example using ‘go-along’ interviews or mobile interviews, where researchers experience place alongside individuals and communities [5-10]; using ‘photovoice’ where participants are asked to document notable or meaningful aspects of their local environment [11,12]; and finally, using approaches that combine and integrate geo-spatial and qualitative methods to understand how local environments are experienced [13-17]. These approaches could be utilised in future work to capture some of those “‘episodic’ moments of city life” [p.2] that are highly valued by individuals and communities, but that may also be taken for granted and undervalued by practitioners as a result.

By the authors’ own admission, this book is not a “‘rule’ book” but a flexible guide where “freedom of expression and creativity” is encouraged [p.14]. I like that the guidelines are flexible and invite practitioners and communities to be creative and playful themselves. This is likely to produce wellbeing in itself and ensure that the uniqueness of cities continues to be celebrated. I am sure that many people who read this book will think of their own ideas in addition to the ones already provided. In this way, I see this book as an important conversation starter, which can provide inspiration and innovation within individual cities.

The book concludes in Chapter 8 by considering the framework as a whole and showing how the concepts within a restorative city are very much aligned with that of a resilient city. In particular, the authors emphasise the need to incorporate wellbeing, mental health and resilience into our cities, in order to cope, adapt and thrive in response to future challenges and that with the recent Covid-19 pandemic, this has never been more important. Roe & McCay argue that as researchers and practitioners, “we have an opportunity to plan, design, develop and deliver cities that help enable people not merely to survive but to thrive” (p.193). I believe that with the knowledge and expertise we now have, that we do not just have an opportunity to do this. Instead, I would argue that we have a moral duty and responsibility to provide environments that are liveable, health-promoting, restorative and resilient.

For too long health and mental health have been an afterthought rather than a priority, resulting in widening inequalities and social injustices. To address this, it is important to translate, disseminate and share knowledge in accessible ways, as well as demand more collaborative planning processes. Restorative Cities fills this much needed gap and offers a clear and accessible framework to guide these important conversations. This is a conversation we all need to have, not just practitioners and researchers, but as citizens; we are all influenced by our respective environments, some more positively than others. Restorative Cities provides the evidence, the inspiration and a call to action. Now we have to act.

For those who are familiar with this literature and already bridging health and planning disciplines, many of the individual components of this book will be familiar, particularly those pillars that are more established. However, one of the strengths of this book is the way that different components of restorative urbanism have been brought together through the framework in a very clear way. In this way, the restorative cities framework is far greater than the sum of its individual parts. Roe & McCay provide a comprehensive overview of the key ways that the built environment can influence mental health. They capture and present complex ideas and theories and bring them together in an accessible form. This means that for those who are new to literature that connects mental health and urban design, this book will be very easy to follow.

This book will be useful for those who are interested in incorporating mental health into planning and want to do more but are not sure where to start. The restorative cities framework and the guidance provided could be useful for students, lecturers, practitioners and researchers alike and could be applied in many different ways. I have envisioned several applications for this framework based on my own experience within planning policy, as a PhD student conducting research on ageing well in place and as a tutor on the topic of Healthy Local Environments. In terms of planning practice, I could see this framework being used to produce audits within cities to determine how restorative they already are, to identify the existing strengths within a city, as well as identify ways in which they could be improved. This could be carried out within local authorities or as part of assignments within modules. I have previously set assignments asking students to conduct ‘health checks’ of their local environments within a Healthy Local Environment module and this framework would be a useful addition to guide this work.

The book emphasises that restorative urbanism “can build incrementally, but it is important that the overarching masterplan be established” [p.197]. Here, the authors have recognised the important role in the power of small or softer interventions in transforming cities that can build cumulatively over time. One way of incorporating this work strategically is by emphasising the importance of mental health within Local Plans or Development Plan Documents (DPDs), or potentially developing Mental Health Supplementary Planning Documents (SPDs) to provide the policy structure to guide development management. In the past, planning policy has been criticised for ‘tokenistic’ references to health [2], but this framework could be applied to implement restorative urbanism more comprehensively within policy. To transparently demonstrate progress and to ensure that progress is in the right direction, local authorities could provide updates through their Annual Monitoring Reports on the different pillars, to demonstrate the ways that they have been implementing these guidelines. Furthermore, existing strategies and future developments could be evaluated through Mental Health Impact Assessments. Whilst there are guides already available for Heath Impact Assessments [3], future work might consider what additional components would be needed to incorporate this broader framework.

A key theme throughout this book is the emphasis on the need for participatory approaches, recognising that “the community is expert in what it needs and designing an inclusive place is a group effort” [p.106]. Such an approach calls for and raises the importance of participatory and community-based planning. I agree with Roe & McCay that it is important to move away from more reactive responses to planning and instead to encourage communities to get involved and demand the cities that they would like to see. For those groups who are more disengaged and disempowered from the planning process, additional efforts will be required to ensure that their perspectives are heard.

A strength of this framework is the recognition of the subjective experiences of place. To understand the different experiences and needs of diverse population groups, requires ‘alternative’ research designs and methodologies that are more qualitative, creative, spatial and participatory [4]. These are increasingly being applied within health geography: for example using ‘go-along’ interviews or mobile interviews, where researchers experience place alongside individuals and communities [5-10]; using ‘photovoice’ where participants are asked to document notable or meaningful aspects of their local environment [11,12]; and finally, using approaches that combine and integrate geo-spatial and qualitative methods to understand how local environments are experienced [13-17]. These approaches could be utilised in future work to capture some of those “‘episodic’ moments of city life” [p.2] that are highly valued by individuals and communities, but that may also be taken for granted and undervalued by practitioners as a result.

By the authors’ own admission, this book is not a “‘rule’ book” but a flexible guide where “freedom of expression and creativity” is encouraged [p.14]. I like that the guidelines are flexible and invite practitioners and communities to be creative and playful themselves. This is likely to produce wellbeing in itself and ensure that the uniqueness of cities continues to be celebrated. I am sure that many people who read this book will think of their own ideas in addition to the ones already provided. In this way, I see this book as an important conversation starter, which can provide inspiration and innovation within individual cities.

The book concludes in Chapter 8 by considering the framework as a whole and showing how the concepts within a restorative city are very much aligned with that of a resilient city. In particular, the authors emphasise the need to incorporate wellbeing, mental health and resilience into our cities, in order to cope, adapt and thrive in response to future challenges and that with the recent Covid-19 pandemic, this has never been more important. Roe & McCay argue that as researchers and practitioners, “we have an opportunity to plan, design, develop and deliver cities that help enable people not merely to survive but to thrive” (p.193). I believe that with the knowledge and expertise we now have, that we do not just have an opportunity to do this. Instead, I would argue that we have a moral duty and responsibility to provide environments that are liveable, health-promoting, restorative and resilient.

For too long health and mental health have been an afterthought rather than a priority, resulting in widening inequalities and social injustices. To address this, it is important to translate, disseminate and share knowledge in accessible ways, as well as demand more collaborative planning processes. Restorative Cities fills this much needed gap and offers a clear and accessible framework to guide these important conversations. This is a conversation we all need to have, not just practitioners and researchers, but as citizens; we are all influenced by our respective environments, some more positively than others. Restorative Cities provides the evidence, the inspiration and a call to action. Now we have to act.

For more information about Restorative Cities: Urban Design for Mental Health and Wellbeing, click here.

About the Author

|

Hannah Grove is a Health Geography PhD student combining qualitative and spatial approaches to explore the supportiveness of local environments for ageing well in place. She has an undergraduate degree in Geography from the University of Sussex, a master’s degree in Town Planning from the University of Brighton. Hannah has previously taught on the topic of Healthy Local Environments at Maynooth University, Ireland and has worked as a Planning Policy Officer in the UK.

@Hannah_Grove |

References

- Urban Design & Mental Health (2016). Policy Brief: The Impact of Urban Design on Mental Health and Wellbeing [Online] Available at: https://www.urbandesignmentalhealth.com/uploads/1/1/4/0/1140302/urban_design_and_mental_health_policy_brief.pdf (Accessed 30th July 2021).

- Carmichael, L., Barton, H., Gray, S. & Lease, H. (2013). Health-integrated planning at the local level in England: Impediments and opportunities. Land Use Policy, 31, 259-266.

- Public Health England (2020). Health Impact Assessment in spatial planning: A guide for local authority public health and planning teams [Online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/929230/HIA_in_Planning_Guide_Sept2020.pdf (Accessed 30th July 2021).

- Handler S. (2014). An Alternative Age Friendly Handbook, Manchester, UK: The University of Manchester Library.

- Carroll, S., Jespersen, A. P. & Troelsen, J. (2020). Going along with older people: exploring age-friendly neighbourhood design through their lens. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 35(2), 555-572.

- Evans, J. & Jones, P. (2011). The walking interview: Methodology, mobility and place. Applied Geography, 31(2), 849-858.

- Finlay, J. M. & Bowman, J. A. (2017). Geographies on the Move: A Practical and Theoretical Approach to the Mobile Interview. The Professional Geographer, 69(2), 263-274.

- Gardner, P. J. (2011). Natural neighborhood networks — Important social networks in the lives of older adults aging in place. Journal of Aging Studies, 25(3), 263-271.

- Kusenbach, M. (2003). Street phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography, 4(3), 455-485.

- Shortt, N. K. & Ross, C. (2021). Children's perceptions of environment and health in two Scottish neighbourhoods. Social Science & Medicine, 283, 114186.

- Mahmood, A., Chaudhury, H., Michael, Y. L., Campo, M., Hay, K. & Sarte, A. (2012). A photovoice documentation of the role of neighborhood physical and social environments in older adults’ physical activity in two metropolitan areas in North America. Social Science & Medicine, 74(8), 1180-1192.

- Van Hees, S., Horstman, K., Jansen, M. & Ruwaard, D. (2017). Photovoicing the neighbourhood: Understanding the situated meaning of intangible places for ageing-in-place. Health & Place, 48(Supplement C), 11-19.

- Bell, S. L., Phoenix, C., Lovell, R. & Wheeler, B. W. (2015). Using GPS and geo-narratives: a methodological approach for understanding and situating everyday green space encounters. Area, 47(1), 88-96.

- Bell, S. L., Wheeler, B. W., & Phoenix, C. (2017). Using Geonarratives to Explore the Diverse Temporalities of Therapeutic Landscapes: Perspectives from “Green” and “Blue” Settings. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 107(1), 93-108.

- Grove, H. (2020). Ageing as well as you can in place: Applying a geographical lens to the capability approach. Social Science & Medicine, 113525.

- Hand, C., Huot, S., Laliberte Rudman, D. & Wijekoon, S. (2017). Qualitative-Geospatial Methods of Exploring Person-Place Transactions in Aging Adults: A Scoping Review. The Gerontologist, 57(3), e47-e61.

- Meijering, L. & Weitkamp, G. (2016). Numbers and narratives: Developing a mixed-methods approach to understand mobility in later life. Social Science & Medicine, 168, 200-206.