Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2021:7;8

CASE STUDY

The Repository: Where Reminiscence becomes Reliving through Synesthetic Architecture

Jian Wei Justin Tan*, Jia Ying Elisabeth Yaw, Yisang Wang, Zdravko Trivic

Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore, Singapore

* corresponding author email: [email protected]

Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore, Singapore

* corresponding author email: [email protected]

Citation: Tan JWJ, Yaw JYE, Wang Y, Trivic Z (2021). The Repository: Where reminiscence becomes reliving through synesthetic architecture. Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 7;8

Introduction

Boasting one of the highest life expectancies but also the lowest fertility rate in the world, it comes as no surprise that Singapore’s population is among the most rapidly ageing across the globe, with an estimate that by 2030, over 22% of Singaporeans will be aged 65 and above (United Nations, 2019). How then do we respond to the inevitable and design with older adults in mind? This essay seeks to explore how synesthetic architecture may be leveraged upon in our urban environment to invoke reminiscence and create a meaningful place for older adults to address their mental health and overall sense of wellbeing.

Reminiscence as a tool for mental health in older adults

According to the World Health Organization (2017), over 20% of adults aged 60 and above suffer from some neurological disorder, with dementia and depression accounting for approximately 5% and 7%, respectively. One of the key risk factors of mental health problems is stress. While stress is experienced by all, older adults face additional challenges, such as the deterioration of physical, sensory and cognitive capacities (Trivic, 2021), the drop of socio-economic status and the loss of sense of purpose, among others, which further accelerate with age. Unfortunately, unlike the physical conditions, which are often easier to detect and address, such additional problems tend to be unrevealed, overlooked or untreated until late.

In a rapidly changing world, it gets increasingly harder for the older generation to find and maintain familiarity and stability. Coupled with the aforementioned stressors that create more anxiety amongst older adults, it is unsurprising that many of them end up feeling lost and disorientated in their built and social environment, losing the ability to adapt and keep up with changes around them. Memory, therefore, is what keeps them grounded, the focal point of reference to make sense of everything that is happening around them, what provides a context for both the present and the past, and fosters the sense of coherence and continuity (Coleman, 1992; Parker, 1999). The act of reminiscing positive memories can improve quality of life and reduce symptoms of depression as the older people draw joy and increased self-esteem from remembering happy memories (Moral et al., 2015). Reminiscence helps senior adults to cope with difficult times and circumstances, enhance problem-solving capacity, adapt to change, find meaning and reconciliation (Bohlmeijer et al., 2007). Moreover, engaging in memory training may also help to prevent cognitive decline and reduce the risk of dementia amongst seniors as they remain active mentally (Hanaoka et al., 2019).

However, there are also kinds of reminiscence that may not necessarily have positive effects, but can also be harmful (Hofer et al., 2017). Fond recollections could also lead to depression if the positive emotions evoked from past memories are not translated into present day behavioural response (Robert, 1963). Obsessive reminiscence, escapist reminiscence and reminiscence for death preparation are associated with emotional vulnerability, psychological distress, bitterness and apathy, among other negative effects (Bohlmeijer et al., 2007; Cappeliez & O’Rourke, 2002; Cully et al., 2011).

Studies have shown that the reminiscence that sparks dialogue between the old and young improves psychological well-being over time (Cappeliez et al., 2005). Research has also shown that reminiscence tends to have greater effect on community-dwelling older adults than those living in care settings (Bohlmeijer et al., 2007). Based on these specific findings, our study focuses on community settings and places used by both younger and older adults, such as void decks, common multi-functional empty spaces beneath public housing blocks in Singapore. Additionally, in contrast to typical active and intentional memory training exercises, our intention is to explore ways to stimulate and strengthen older adults psychological wellbeing and cognitive skills in a subtler and more integrated manner. Hence, we further look into the concept of synaesthesia as a potential means for achieving such goals.

Synaesthetic architecture to complement reminiscence

Synaesthesia can be defined is a condition that results from the blending of senses (joint sensation), which are typically not connected, whereby the stimulation of one sensory system triggers an involuntary reaction in another sense (or senses) (Cytowic, 2002; Simner et al., 2006; Ward & Cytowic, 2006). Psychological (and social) wellbeing are often triggered by the fragmented embodied and emotional encounters with space (Cytowic, 2002; Nanda & Solovyova, 2005), whereby all senses are stimulated simultaneously. According to Spence (2020), more adequate term for synesthetic design in architecture is cross-modal correspondence or multi-sensory interaction. Bringing together all five basic senses of sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch, triggers positive emotions (Li et al., 2020), invokes a higher sense of balance and navigation (movement), strengthens sense of ego (purpose and achievement) and enhances sense of belonging (social encounters and community bonding), all which are fundamental for one’s overall sense of wellbeing (Bozovic-Stamenovic, 2013; Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002). In general, enhanced sensorial engagement could contribute to improving brain health as it helps to trigger the recall of long-term memories as well as to consolidate and establish memories (Assed et al., 2016). The use of reminiscence, complemented with synaesthetic architecture, could hence be used to create integrated healthful places that are supportive to senior adults.

In synaesthetic architecture, it is important to place focus on all senses as the senses of sight and sound typically dominate over other senses (e.g., Degen, 2008; Zardini, 2005). The senses of touch and smell are particularly helpful in the recollection of memories. The sense of touch, as the sensory mode that integrates our experiences of the world with that of ourselves, is the “mother of all senses” (Pallasmaa, 2005). The sense of smell is the primary sense associated with memory. Due to the anatomy of the brain, olfactory signals are able to be transmitted quickly to the limbic system in charge of the formation of memories. This relation also extends to emotions, creating a three-way link between smells, emotions and memories (Rokni & Murthy, 2014). Moreover, studies have shown that smell-evoked memories tend to be more positive than those triggered by other cues (Herz, 2016). Exposing people to familiar smells from their past could help to strengthen their recollection of their positive past memories be it people or places of significance (El Haj, 2018).

Taking the research on the benefits of synesthetic architecture and reminiscence into account, we conducted site analysis of one housing precinct in Singapore followed by design exploration to examine how these concepts could be applied to and acted upon in order to improve the health of our seniors. Understanding activity and sensory rhythms of daily life in the community helps us contextualise our design proposal better and formulate the design aims. Our initial question was: how can we embed the concepts of reminiscence and synaesthesia into design that would enrich everyday neighbourhood spaces for all residents, while focusing on supporting older adults’ mental and social wellbeing?

Reminiscence as a tool for mental health in older adults

According to the World Health Organization (2017), over 20% of adults aged 60 and above suffer from some neurological disorder, with dementia and depression accounting for approximately 5% and 7%, respectively. One of the key risk factors of mental health problems is stress. While stress is experienced by all, older adults face additional challenges, such as the deterioration of physical, sensory and cognitive capacities (Trivic, 2021), the drop of socio-economic status and the loss of sense of purpose, among others, which further accelerate with age. Unfortunately, unlike the physical conditions, which are often easier to detect and address, such additional problems tend to be unrevealed, overlooked or untreated until late.

In a rapidly changing world, it gets increasingly harder for the older generation to find and maintain familiarity and stability. Coupled with the aforementioned stressors that create more anxiety amongst older adults, it is unsurprising that many of them end up feeling lost and disorientated in their built and social environment, losing the ability to adapt and keep up with changes around them. Memory, therefore, is what keeps them grounded, the focal point of reference to make sense of everything that is happening around them, what provides a context for both the present and the past, and fosters the sense of coherence and continuity (Coleman, 1992; Parker, 1999). The act of reminiscing positive memories can improve quality of life and reduce symptoms of depression as the older people draw joy and increased self-esteem from remembering happy memories (Moral et al., 2015). Reminiscence helps senior adults to cope with difficult times and circumstances, enhance problem-solving capacity, adapt to change, find meaning and reconciliation (Bohlmeijer et al., 2007). Moreover, engaging in memory training may also help to prevent cognitive decline and reduce the risk of dementia amongst seniors as they remain active mentally (Hanaoka et al., 2019).

However, there are also kinds of reminiscence that may not necessarily have positive effects, but can also be harmful (Hofer et al., 2017). Fond recollections could also lead to depression if the positive emotions evoked from past memories are not translated into present day behavioural response (Robert, 1963). Obsessive reminiscence, escapist reminiscence and reminiscence for death preparation are associated with emotional vulnerability, psychological distress, bitterness and apathy, among other negative effects (Bohlmeijer et al., 2007; Cappeliez & O’Rourke, 2002; Cully et al., 2011).

Studies have shown that the reminiscence that sparks dialogue between the old and young improves psychological well-being over time (Cappeliez et al., 2005). Research has also shown that reminiscence tends to have greater effect on community-dwelling older adults than those living in care settings (Bohlmeijer et al., 2007). Based on these specific findings, our study focuses on community settings and places used by both younger and older adults, such as void decks, common multi-functional empty spaces beneath public housing blocks in Singapore. Additionally, in contrast to typical active and intentional memory training exercises, our intention is to explore ways to stimulate and strengthen older adults psychological wellbeing and cognitive skills in a subtler and more integrated manner. Hence, we further look into the concept of synaesthesia as a potential means for achieving such goals.

Synaesthetic architecture to complement reminiscence

Synaesthesia can be defined is a condition that results from the blending of senses (joint sensation), which are typically not connected, whereby the stimulation of one sensory system triggers an involuntary reaction in another sense (or senses) (Cytowic, 2002; Simner et al., 2006; Ward & Cytowic, 2006). Psychological (and social) wellbeing are often triggered by the fragmented embodied and emotional encounters with space (Cytowic, 2002; Nanda & Solovyova, 2005), whereby all senses are stimulated simultaneously. According to Spence (2020), more adequate term for synesthetic design in architecture is cross-modal correspondence or multi-sensory interaction. Bringing together all five basic senses of sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch, triggers positive emotions (Li et al., 2020), invokes a higher sense of balance and navigation (movement), strengthens sense of ego (purpose and achievement) and enhances sense of belonging (social encounters and community bonding), all which are fundamental for one’s overall sense of wellbeing (Bozovic-Stamenovic, 2013; Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002). In general, enhanced sensorial engagement could contribute to improving brain health as it helps to trigger the recall of long-term memories as well as to consolidate and establish memories (Assed et al., 2016). The use of reminiscence, complemented with synaesthetic architecture, could hence be used to create integrated healthful places that are supportive to senior adults.

In synaesthetic architecture, it is important to place focus on all senses as the senses of sight and sound typically dominate over other senses (e.g., Degen, 2008; Zardini, 2005). The senses of touch and smell are particularly helpful in the recollection of memories. The sense of touch, as the sensory mode that integrates our experiences of the world with that of ourselves, is the “mother of all senses” (Pallasmaa, 2005). The sense of smell is the primary sense associated with memory. Due to the anatomy of the brain, olfactory signals are able to be transmitted quickly to the limbic system in charge of the formation of memories. This relation also extends to emotions, creating a three-way link between smells, emotions and memories (Rokni & Murthy, 2014). Moreover, studies have shown that smell-evoked memories tend to be more positive than those triggered by other cues (Herz, 2016). Exposing people to familiar smells from their past could help to strengthen their recollection of their positive past memories be it people or places of significance (El Haj, 2018).

Taking the research on the benefits of synesthetic architecture and reminiscence into account, we conducted site analysis of one housing precinct in Singapore followed by design exploration to examine how these concepts could be applied to and acted upon in order to improve the health of our seniors. Understanding activity and sensory rhythms of daily life in the community helps us contextualise our design proposal better and formulate the design aims. Our initial question was: how can we embed the concepts of reminiscence and synaesthesia into design that would enrich everyday neighbourhood spaces for all residents, while focusing on supporting older adults’ mental and social wellbeing?

Method and Results

A small public housing precinct within the Bangkit neighbourhood in Singapore, situated between the commercial centre, the train station and a large park, was chosen as the site of investigation and design intervention. The precinct includes several typical public amenities, such as children’s playgrounds, community gardens, fitness corners and sports courts. The population of the chosen neighbourhood has a large percentage of older residents, hence making it an appropriate site choice.

An on-site study by three student researchers was conducted in an attempt to investigate the relationship between everyday pedestrian activity patterns and the sensory qualities of places in the neighbourhood. Two separate observations were conducted at fourteen fixed locations within the neighbourhood during the morning, midday, and evening periods. These observation locations were identified during a preliminary walkthrough in the neighbourhood as the key nodes of activity, which can be further categorised as accessibility points and amenity features, such as playgrounds and community gardens. Such a method has also been informed by other observational studies (e.g., Marusic, 2011; Trivic et al., 2020; Trivic, 2021; Whyte, 1980; Yuen & Nair, 2019).

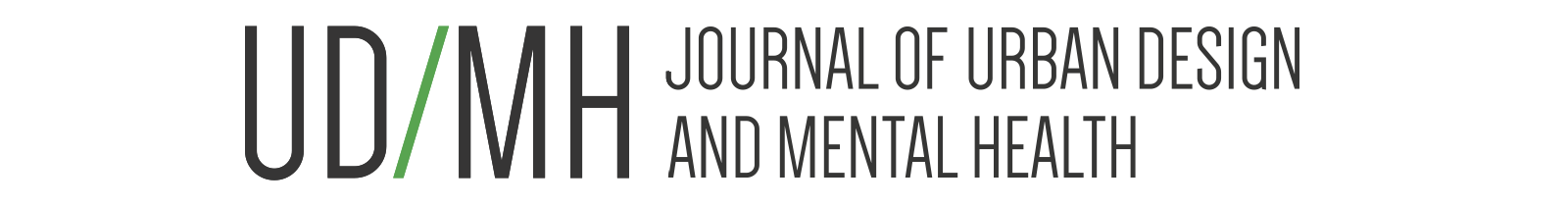

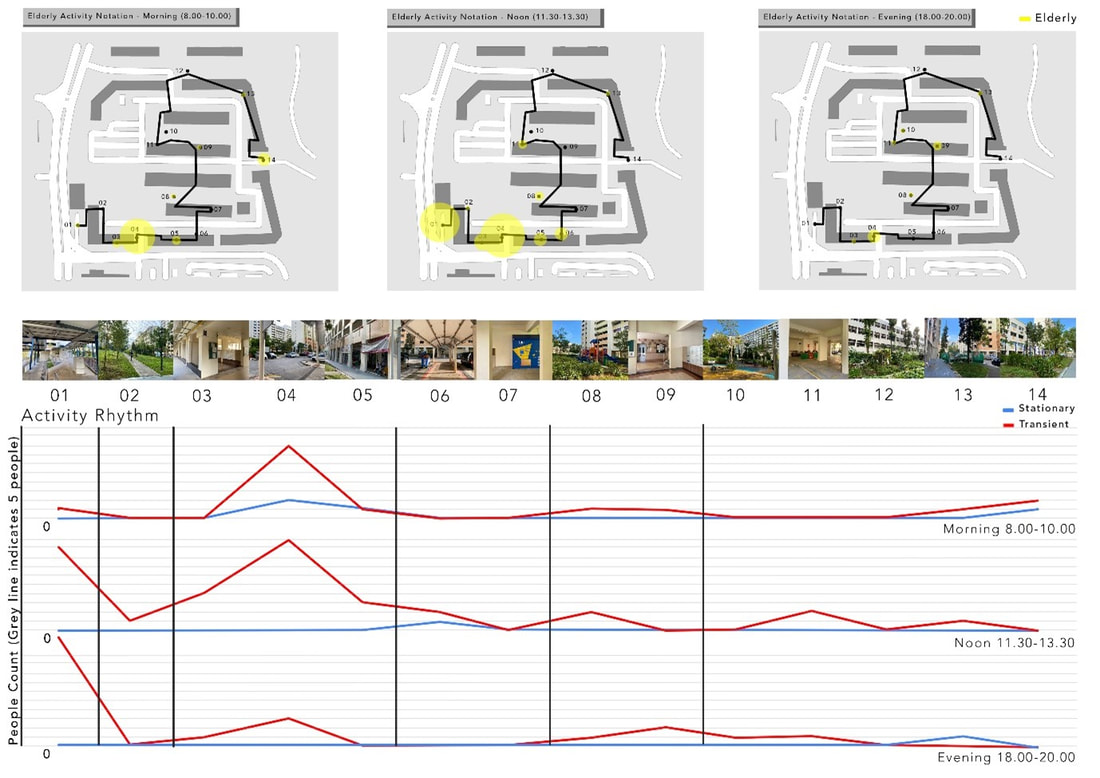

Informed by the “snapshot” technique developed by Gehl and Svarre (2013), the first observation focused on noting down the number of people present at each location within a short period of time (5 minutes) and whether the nature of their activity was transient or stationary (Figure 1). We also took note of the different age groups at these locations, based on our estimation. This was done to identify specific places in the neighbourhood that are most frequently visited and used by the older adults and whether there are opportunities for prolonged interactions to occur, be it interpersonal or with the physical environment.

An on-site study by three student researchers was conducted in an attempt to investigate the relationship between everyday pedestrian activity patterns and the sensory qualities of places in the neighbourhood. Two separate observations were conducted at fourteen fixed locations within the neighbourhood during the morning, midday, and evening periods. These observation locations were identified during a preliminary walkthrough in the neighbourhood as the key nodes of activity, which can be further categorised as accessibility points and amenity features, such as playgrounds and community gardens. Such a method has also been informed by other observational studies (e.g., Marusic, 2011; Trivic et al., 2020; Trivic, 2021; Whyte, 1980; Yuen & Nair, 2019).

Informed by the “snapshot” technique developed by Gehl and Svarre (2013), the first observation focused on noting down the number of people present at each location within a short period of time (5 minutes) and whether the nature of their activity was transient or stationary (Figure 1). We also took note of the different age groups at these locations, based on our estimation. This was done to identify specific places in the neighbourhood that are most frequently visited and used by the older adults and whether there are opportunities for prolonged interactions to occur, be it interpersonal or with the physical environment.

Figure 1. Activity patterns (red – transient activities; blue – stationary activities)

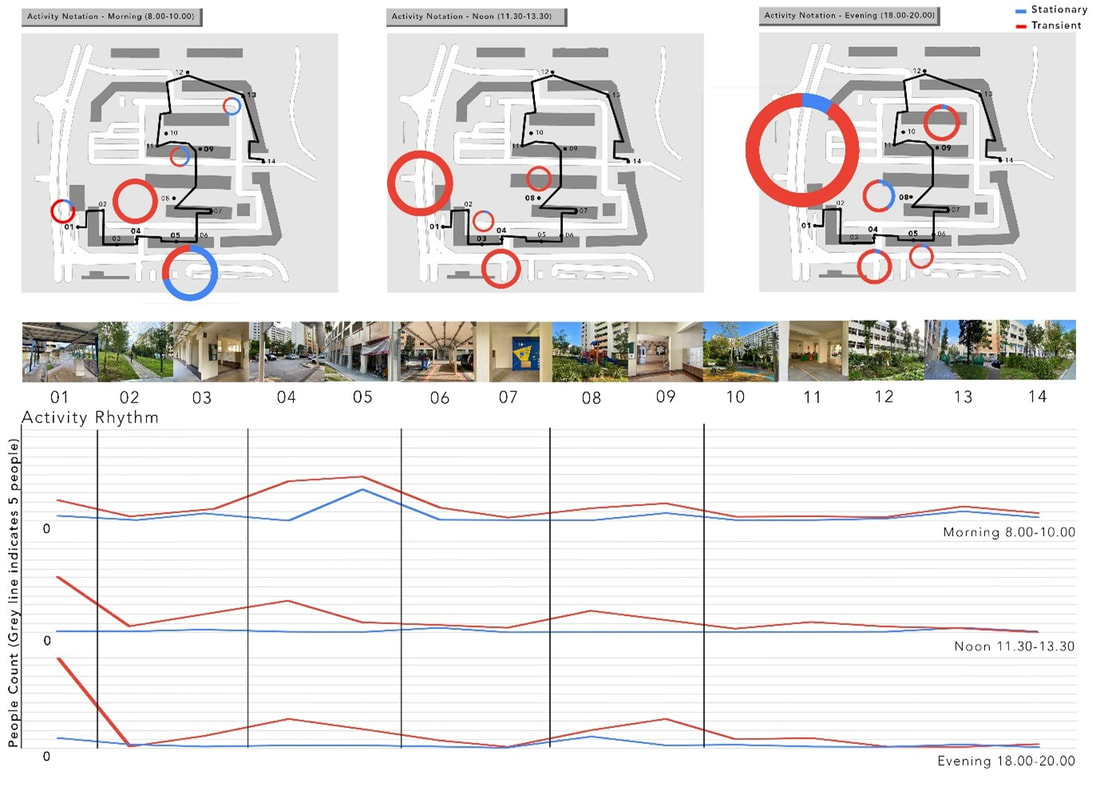

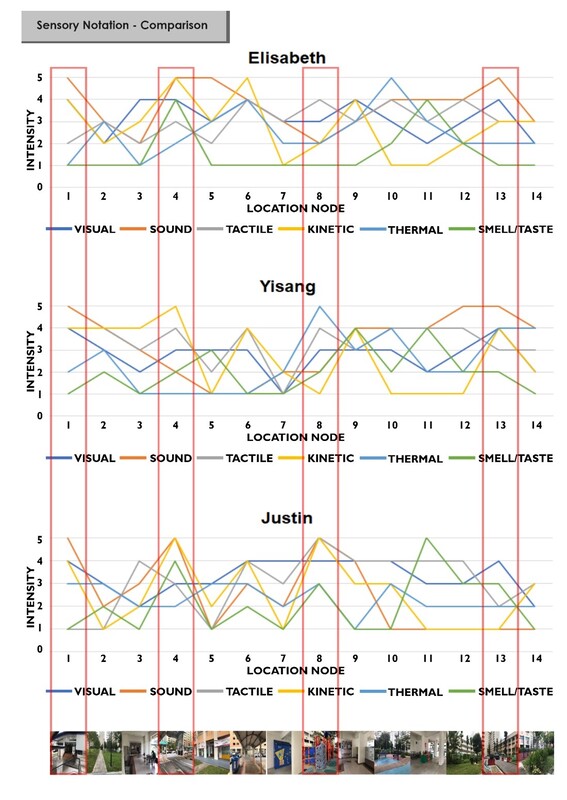

The second observation was a study of sensory qualities of each of the fourteen locations selected. Sensory assessment was inspired by the notation systems developed by Lucas and Romice (2010) and sensory charts by Malnar and Vodvarka (2004). Three observers independently recorded and assessed the intensity for each sensory stimulus (visual, sound, tactile, kinetic, thermal, smell/taste) on a 5-point scale, whereby “5” denotes highest intensity (Figure 2). Similarly, the pleasantness of the sensory experience was also rated for each sense at each observation location and by each student researcher (Figure 3). While these assessments are highly subjective, they prompted comparisons and further discussions. Our intent was not to aggregate the average scores from three researchers but rather to observe similarities and differences in evaluation.

Figure 2 - Sensory notation – intensity level (rectangle bound highlights nodes with highest intensity average across all senses)

Figure 3 - Sensory notation – pleasantness level (rectangle bound highlights nodes with highest pleasantness average across all senses)

Key findings and implications for design

Our findings revealed that the precinct was overall relatively poor in sensory qualities, (Figures 2 and 3) as well as quiet in terms of activity, which are predominantly transient and occur mostly during the morning and evening peak hours (Figure 1). No conclusive argument could be made regarding the relationship between overall sensory experience and activity. However, we observed that the overall attractiveness of a place was linked to sensorial engagement, primarily tactile and visual, with the higher intensity of stationary activities recorded at places that are sensory richer.

There were places, however, that were underutilised almost at all times. We observed that some spaces catering for stationary activity, such as the exercise corner (point 10 in Figures 1, 2 and 3), were being underutilised by the older adults either due to a lack of interest or a preference for a sedentary lifestyle. Upon further evaluation, however, we noted that the exercise equipment (e.g., pull-up bars and parallel dip bars) at fitness corners did not cater for all the ranges of older adults’ abilities. While the space is visually engaging and quiet, and although it is clearly designed for tactile and kinetic engagement, the pleasantness of utilising such features decreases due to high exposure to sun and low thermal comfort. Moreover, only a limited number of seats without proper backrest or armrest was provided around this area. Unfortunately, there are many common areas that clearly cater to older residents and due to a lack of leisure facilities for them, they tend to more frequently utilise a nearby market area, or, yet in smaller numbers, the void deck spaces.

We noticed that the older residents were more active in the morning and late afternoon, with the higher number congregating at nodes 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6 (hotspots for stationary activities), of which points 3-6 are parts of the void deck spaces, as shown in Figure 4. Void decks are typically not sensory rich settings and they are not intensively used. While they are monotonous in terms of visual and tactile stimulation, with sparse fixed seating amenities and numerous columns, they also provide shelter and, thus, good thermal comfort, less slippery surfaces, and a quite environment conducive to different types of activities.

There were places, however, that were underutilised almost at all times. We observed that some spaces catering for stationary activity, such as the exercise corner (point 10 in Figures 1, 2 and 3), were being underutilised by the older adults either due to a lack of interest or a preference for a sedentary lifestyle. Upon further evaluation, however, we noted that the exercise equipment (e.g., pull-up bars and parallel dip bars) at fitness corners did not cater for all the ranges of older adults’ abilities. While the space is visually engaging and quiet, and although it is clearly designed for tactile and kinetic engagement, the pleasantness of utilising such features decreases due to high exposure to sun and low thermal comfort. Moreover, only a limited number of seats without proper backrest or armrest was provided around this area. Unfortunately, there are many common areas that clearly cater to older residents and due to a lack of leisure facilities for them, they tend to more frequently utilise a nearby market area, or, yet in smaller numbers, the void deck spaces.

We noticed that the older residents were more active in the morning and late afternoon, with the higher number congregating at nodes 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6 (hotspots for stationary activities), of which points 3-6 are parts of the void deck spaces, as shown in Figure 4. Void decks are typically not sensory rich settings and they are not intensively used. While they are monotonous in terms of visual and tactile stimulation, with sparse fixed seating amenities and numerous columns, they also provide shelter and, thus, good thermal comfort, less slippery surfaces, and a quite environment conducive to different types of activities.

Figure 4 - Older adults’ activity patterns; red – transient activities; blue – stationary activities (charts); yellow – older adults’ activity hotspots (maps)

We hence identified these places as good opportunities to incorporate synaesthetic architecture principles, since people tend to prefer familiar environments (Bozovic-Stamenovic, 2015). Informed by our findings, however, we concluded that merely creating a sensory experience would not be compelling enough to encourage prolonged activity in a space. Therefore, as void decks are also utilised by the residents across all age groups, we also identified potential to foster a sense of connectedness and belonging (with both space and the community) that may improve the mental and social health of older residents (O’Rourke et al., 2018).

All the above informed the main goals of our conceptual design proposal, which are to activate the largely underutilised and transitional void deck space and to create a supportive setting for older residents, while also attracting dialogue with other age groups. To achieve this our design combines the tools of reminiscence and synaesthetic architecture, enhanced by novel sensing and immersive technologies, to envision a repository of memories and stories shared by the residents in the community and brought to life through a sensorial experience. Our hypothesis is that creating such a sharing and immersive setting would contribute to the mental and social wellbeing of the senior residents.

All the above informed the main goals of our conceptual design proposal, which are to activate the largely underutilised and transitional void deck space and to create a supportive setting for older residents, while also attracting dialogue with other age groups. To achieve this our design combines the tools of reminiscence and synaesthetic architecture, enhanced by novel sensing and immersive technologies, to envision a repository of memories and stories shared by the residents in the community and brought to life through a sensorial experience. Our hypothesis is that creating such a sharing and immersive setting would contribute to the mental and social wellbeing of the senior residents.

Conceptual design proposal: The Repository

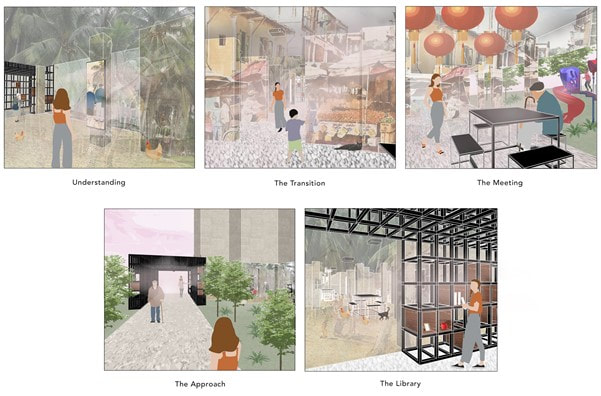

The Repository (Figures 5 and 6) aims to transform void decks into “living libraries” that function as places to explore and be engaged. Life stories of the residents can be collated in a participatory manner and catalogued and collated into different themes, such as ‘Kampong (village) living’ or ‘old Chinatown’. A series of synesthetic interventions are employed at different void deck spaces to immerse the users in a sensorial retelling of the aforementioned themes when activated by motion sensors. The design is envisioned as journey, whereby the interaction can be customised by the users and in negotiation with other users.

Figure 5 - A journey through The Repository

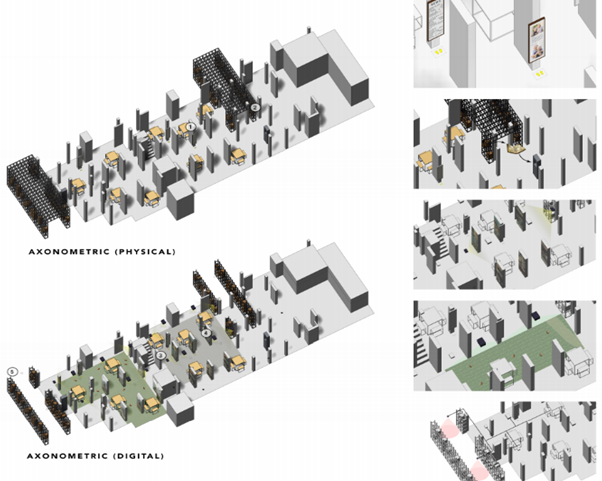

Figure 6 - The Repository: interplay between the physical (furniture, board games, physical library of books and objects) and digital (LED screens, projectors, motion sensors) interface

The design substantially enriches the void deck spaces, especially in visual and tactile senses, but also olfactory and kinetic, with an added aim of triggering memories and social interaction. Visual and audio cues are integrated through the use of projectors and speakers installed in the void decks that transform the space into a thematic backdrop when triggered by occupancy. Fragrance atomisers are employed to release scents that are common to the specific theme at regular intervals across the void decks once activated. Tactile elements are present in the form of both physical memorabilia (see Figure 5, image 5) for users to interact with (such as shared personal belongings from the community members, e.g. photographs, pieces of clothes, books and other objects), as well as physical activities catered for the various physical dexterity and capabilities of the users that evoke memories of past entertainment, such as childhood games. Engaging the sense of touch grounds the design into reality and makes it evident that the reminiscence of memories the design hopes to achieve goes beyond mere recollection but a genuine revisit of past memories. A combination of physical (analogue) and virtual (digital) features provides diverse opportunities for intuitive interaction and thus respects a range of choices, preferences and abilities coming from different types of users.

All the design intents expressed above culminate to recreate the memories that the older adults hold so dearly through an immersive and comprehensive environment. The intention is not to overwhelm their sense but to evoke the higher senses of balance and navigation, ego and belonging. By creating a holistic environment that engages the various senses, as well as cognitive and symbolic dimensions of experience, the goal is to go beyond recreating scenes from the past but to help the older residents relive them and create new shared memories to cherish as they interact with both the synesthetic architecture and other users.

The “living libraries” are envisioned to be recreated across different void decks, each bearing a specific theme. The intentional segregation of void decks by themes also serve as a wayfinding tool for those suffering from Alzheimer’s and other cognitive disorders by strengthening “memory connections” (Smith, n.d.).

The Repository increases the opportunities for intergenerational interactions, which has also been proven to stimulate cognitive functioning (Tan, 2017) and social wellbeing. By locating the proposed design at the very heart of the residential neighbourhood, we hope to sculpt a venue where understanding and empathy can be fostered amongst the different age groups through the retelling of personal stories from the past and novel means of engagement. The incorporation of games and playful engagement with the digital interface hopes not only to enrich leisure opportunities for the older residents in their neighbourhood, but also to attract youth and provide more instances for intergenerational interaction. Weaving through the void decks and past the various precinct amenities, such as playgrounds and childcare centre, the deign also enables these interactive scapes to be incorporated into the children’s playtime, injecting more life into these environments.

All the design intents expressed above culminate to recreate the memories that the older adults hold so dearly through an immersive and comprehensive environment. The intention is not to overwhelm their sense but to evoke the higher senses of balance and navigation, ego and belonging. By creating a holistic environment that engages the various senses, as well as cognitive and symbolic dimensions of experience, the goal is to go beyond recreating scenes from the past but to help the older residents relive them and create new shared memories to cherish as they interact with both the synesthetic architecture and other users.

The “living libraries” are envisioned to be recreated across different void decks, each bearing a specific theme. The intentional segregation of void decks by themes also serve as a wayfinding tool for those suffering from Alzheimer’s and other cognitive disorders by strengthening “memory connections” (Smith, n.d.).

The Repository increases the opportunities for intergenerational interactions, which has also been proven to stimulate cognitive functioning (Tan, 2017) and social wellbeing. By locating the proposed design at the very heart of the residential neighbourhood, we hope to sculpt a venue where understanding and empathy can be fostered amongst the different age groups through the retelling of personal stories from the past and novel means of engagement. The incorporation of games and playful engagement with the digital interface hopes not only to enrich leisure opportunities for the older residents in their neighbourhood, but also to attract youth and provide more instances for intergenerational interaction. Weaving through the void decks and past the various precinct amenities, such as playgrounds and childcare centre, the deign also enables these interactive scapes to be incorporated into the children’s playtime, injecting more life into these environments.

Conclusion

Our conceptual proposal seeks to provide a more accessible, approachable, active, context- and user-sensitive response to aging and mental health. Accordingly, we offer a softer approach that is woven into the built and social fabric of daily living environment to build strong support system for ageing in place.

There are several limitations to this small study. The findings provide only a snapshot of activities in the precinct, and may have not captured activity rhythms comprehensively, despite observations being done at different times of the day. This was further influenced by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, due to which people tend use communal areas less frequently. Sensory assessment is challenging and subjective. it was done by three young student researchers, which may not reflect the sensory experience of older residents. Further studies should involve older adults directly, as it would inform the design decision better.

The prospect of an ageing population may seem daunting to address, but it would be irresponsible to disregard the older generations and isolate them from urban design. Our design is only an exploratory attempt to address these issues, which would require further iterations. The design entails an active engagement of the residents to co-create the libraries and it would, thus, reveal its full potential only through careful participatory process. Nevertheless, reminiscing proposed in our design offers an outlet for the older adults to find familiarity in the ever-changing world. The most valued resource we have as humans are the stories and memories that we hold. The Repository instils a renewed sense of belonging for the elderly, breaking the barriers of stigma against the aged. In this space, memories are not just stored, not just re-lived, but also continually being created, co-created and re-created.

There are several limitations to this small study. The findings provide only a snapshot of activities in the precinct, and may have not captured activity rhythms comprehensively, despite observations being done at different times of the day. This was further influenced by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, due to which people tend use communal areas less frequently. Sensory assessment is challenging and subjective. it was done by three young student researchers, which may not reflect the sensory experience of older residents. Further studies should involve older adults directly, as it would inform the design decision better.

The prospect of an ageing population may seem daunting to address, but it would be irresponsible to disregard the older generations and isolate them from urban design. Our design is only an exploratory attempt to address these issues, which would require further iterations. The design entails an active engagement of the residents to co-create the libraries and it would, thus, reveal its full potential only through careful participatory process. Nevertheless, reminiscing proposed in our design offers an outlet for the older adults to find familiarity in the ever-changing world. The most valued resource we have as humans are the stories and memories that we hold. The Repository instils a renewed sense of belonging for the elderly, breaking the barriers of stigma against the aged. In this space, memories are not just stored, not just re-lived, but also continually being created, co-created and re-created.

Acknowledgements

The content presented in this article was produced during the course “City and Senses: Multi-sensory Approach to Urbanism '' taught in AY2020/21 by Dr Zdravko Trivic at the Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore. Special thanks to Dr Simone Shu-Yeng Chung and her studio members and Dr Ruzica Bozovic-Stamenovic from NUS for providing valuable feedback through a workshop and a guest lecture.

About the Authors

|

Jian Wei Justin Tan, B.A(Arch) is currently undergoing his Masters studies at the Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore. He is passionate about understanding local cultures and his recent travels have brought him across Southeast Asia as he seeks to explore the cultures of the neighbouring countries in his region.

|

|

Jia Ying Elisabeth Yaw, B.A(Arch) is currently pursuing a Masters in Architecture in the National University of Singapore, School of Design and Environment. Her interests include exploring how design could create socially supportive neighbourhoods with better integration between people and the environment.

|

|

Zdravko Trivic, PhD is Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore. His research interests include: multi-sensorial urbanism, health-supportive and ageing-friendly neighbourhood design, urban space in high-density contexts, creative placemaking and community participation.

|

References

Assed, M. M., de Carvalho, M., Rocca, C., & Serafim, A. P. (2016). Memory training and benefits for quality of life in the elderly: A case report. Dementia & Neuropsychologia, 10(2), 152–155. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-5764-2016DN1002012

Bohlmeijer, E., Roemer, M., Cuijpers, P., & Smit, F. (2007). The effects of reminiscence on psychological well-being in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 11(3):291–300. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963547. PMID: 17558580.

Bozovic-Stamenovic, R. (2013). Synesthetic architecture for wellbeing - concept and contradictions. In R. Bogdanovic (Ed.). On Architecture (pp. 510-522). Belgrade: STRAND Sustainable Urban Society Association. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/8454595/SYNESTHETIC_ARCHITECTURE_FOR_WELLBEING_CONCEPT_AND_CONTRADICTIONS

Bozovic-Stamenovic, R. (2015). A supportive healthful housing environment for ageing: Singapore experiences and potentials for improvements. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 25(4), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2015.1116195

Butler, R. N. (1963). The life-review: An interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry, 26(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339

Cappeliez, P., & O’Rourke, N. (2002). Personality traits and existential concerns as predictors of the functions of reminiscence in older adults. Journal of Gerontology, 57(2), P116–P123. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.2.P116

Cappeliez, P., O'Rourke, N., & Chaudhury, H. (2005). Functions of reminiscence and mental health in later life. Aging & Mental Health, 9(4), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860500131427

Coleman, P. G. (1992). Personal adjustment in late life: successful aging. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 2(1): 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259800003014

Cully, J. A., LaVoie, D., & Gfeller, J. D. (2001). Reminiscence, personality, and psychological functioning in older adults. Gerontologist, 41(1), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.1.89

Cytowic, R. E. (2002). Synesthesia: A union of the senses. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Degen, M. M. (2008). Sensing cities: Regenerating public life in Barcelona and Manchester. London: Routledge.

El Haj, M., Gandolphe, M. C., Gallouj, K., Kapogiannis, D., & Antoine, P. (2017). From nose to memory: the involuntary nature of odor-evoked autobiographical memories in Alzheimer's disease. Chemical senses, 43(1), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjx064

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional wellbeing. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00431

Gehl, J., & Svarre, B. (2013). How to study public life. Washington: Island Press.

Hanaoka, H., Muraki, T., & Okamura, H. (2019). Study of aromas as reminiscence triggers in community-dwelling older adults in Japan. Journal of Rural Medicine: JRM, 14(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.2185/jrm.2982

Herz R. S. (2016). The role of odor-evoked memory in psychological and physiological health. Brain sciences, 6(3), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci6030022

Hofer, J., Busch, H., Poláčková Šolcová, I., & Tavel, P. (2017). When reminiscence is harmful: The relationship between self-negative reminiscence functions, need satisfaction, and depressive symptoms among elderly people from Cameroon, the Czech Republic, and Germany. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 18(2), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9731-3

Li, P., Wu, C., & Spence, C. (2020). Multisensory perception and positive emotion: Exploratory study on mixed item set for apparel e-customization. Textile Research Journal, 90(17–18), 2046–2057. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040517520909359

Lucas, R.; Romice, O. (2010). Assessing the multi-sensory qualities of urban space: A methodological approach and notational system for recording and designing the multi-sensory experience of urban space. PsyEcology, 1(2), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1174/217119710791175678

Malnar, J. M., Vodvarka, F. (2004). Sensory design. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Marusic, B. G. (2011). Analysis of patterns of spatial occupancy in urban open space using behaviour maps and GIS. Urban Design International, 16(1), 36–50. doi:http://dx.doi.org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1057/udi.2010.20

Moral, J. C. M., Terrero, F. B. F., Galán, A. S., & Rodríguez, T. M. (2015). Effect of integrative reminiscence therapy on depression, well-being, integrity, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in older adults. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936968

Nanda, U., Solovyova, I. (2005). The embodiment of the eye in architectural education. In E. Harder (Ed.). Writings in Architectural Education (pp. 150–164). Copenhagen: EAAE. Retrieved from http://ndl.ethernet.edu.et/bitstream/123456789/47553/1/71.pdf#page=152

O’Rourke, H.M., Collins, L. & Sidani, S. (2018). Interventions to address social connectedness and loneliness for older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatrics, 18, 214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0897-x

Pallasmaa, J. (2005). The eyes of the skin. Chichester: Wiley.

Parker, R. G. (1999). Reminiscence as continuity: Comparison of young and older adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 5(2): 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022931111622

Rokni, D., Murthy, V. N. (2014). Analysis and synthesis in olfaction. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 5(10), 870-872. https://doi.org/10.1021/cn500199n

Simner, J., Mulvenna, C., Sagiv, N., Tsakanikos, E., Witherby, S. A., Fraser, C., Scott, K., & Ward, J. (2006). Synaesthesia: The prevalence of atypical cross-modal experiences. Perception, 35(8), 1024–1033. https://doi.org/10.1068/p5469

Smith, M. (n.d.). Preventing Alzheimer's disease. Retrieved July 8, 2021, from https://www.helpguide.org/articles/alzheimers-dementia-aging/preventing-alzheimers-disease.htm#

Tan, S.-A. (2017, September 2). Call to promote inter-generational bonding to boost elderly's well-being. The Straits Times, Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/children-bring-smiles-to-elderly-faces

Trivic, Z., Tan, B.K., Mascarenhas, N., & Duong, Q. (2020). Capacities and impacts of community arts and culture initiatives in Singapore. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 50(2), 85–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2020.1720877

Trivic, Z. (2021). a study of older adults’ perception of high-density housing neighbourhoods in singapore: multi-sensory perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18: 6880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph18136880

United Nations (UN), Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019: Volume 1: Comprehensive Tables. New York: United Nations. Retrieved July 8, 2021, from https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Volume-I_Comprehensive-Tables.pdf

Whyte, W. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Washington: The Conservation Foundation.

World Health Organization. (2017, December 12). Mental health of older adults. Retrieved July 8, 2021, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults

Yuen, B., & Nair, P. (2019). Investigating space, activities and social dynamics. In B. Yuen (Ed.), Ageing and the built environment in Singapore (pp. 175–219). Cham: Springer.

Zardini, M. (2005). Toward a sensorial urbanism. In M. Zardini (Ed.). Sense of the city: An alternate approach to urbanism (pp. 17–27). Baden: Lars Müller Publishers; Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Bohlmeijer, E., Roemer, M., Cuijpers, P., & Smit, F. (2007). The effects of reminiscence on psychological well-being in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 11(3):291–300. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963547. PMID: 17558580.

Bozovic-Stamenovic, R. (2013). Synesthetic architecture for wellbeing - concept and contradictions. In R. Bogdanovic (Ed.). On Architecture (pp. 510-522). Belgrade: STRAND Sustainable Urban Society Association. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/8454595/SYNESTHETIC_ARCHITECTURE_FOR_WELLBEING_CONCEPT_AND_CONTRADICTIONS

Bozovic-Stamenovic, R. (2015). A supportive healthful housing environment for ageing: Singapore experiences and potentials for improvements. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 25(4), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2015.1116195

Butler, R. N. (1963). The life-review: An interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry, 26(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339

Cappeliez, P., & O’Rourke, N. (2002). Personality traits and existential concerns as predictors of the functions of reminiscence in older adults. Journal of Gerontology, 57(2), P116–P123. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.2.P116

Cappeliez, P., O'Rourke, N., & Chaudhury, H. (2005). Functions of reminiscence and mental health in later life. Aging & Mental Health, 9(4), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860500131427

Coleman, P. G. (1992). Personal adjustment in late life: successful aging. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 2(1): 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259800003014

Cully, J. A., LaVoie, D., & Gfeller, J. D. (2001). Reminiscence, personality, and psychological functioning in older adults. Gerontologist, 41(1), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.1.89

Cytowic, R. E. (2002). Synesthesia: A union of the senses. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Degen, M. M. (2008). Sensing cities: Regenerating public life in Barcelona and Manchester. London: Routledge.

El Haj, M., Gandolphe, M. C., Gallouj, K., Kapogiannis, D., & Antoine, P. (2017). From nose to memory: the involuntary nature of odor-evoked autobiographical memories in Alzheimer's disease. Chemical senses, 43(1), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjx064

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional wellbeing. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00431

Gehl, J., & Svarre, B. (2013). How to study public life. Washington: Island Press.

Hanaoka, H., Muraki, T., & Okamura, H. (2019). Study of aromas as reminiscence triggers in community-dwelling older adults in Japan. Journal of Rural Medicine: JRM, 14(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.2185/jrm.2982

Herz R. S. (2016). The role of odor-evoked memory in psychological and physiological health. Brain sciences, 6(3), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci6030022

Hofer, J., Busch, H., Poláčková Šolcová, I., & Tavel, P. (2017). When reminiscence is harmful: The relationship between self-negative reminiscence functions, need satisfaction, and depressive symptoms among elderly people from Cameroon, the Czech Republic, and Germany. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 18(2), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9731-3

Li, P., Wu, C., & Spence, C. (2020). Multisensory perception and positive emotion: Exploratory study on mixed item set for apparel e-customization. Textile Research Journal, 90(17–18), 2046–2057. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040517520909359

Lucas, R.; Romice, O. (2010). Assessing the multi-sensory qualities of urban space: A methodological approach and notational system for recording and designing the multi-sensory experience of urban space. PsyEcology, 1(2), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1174/217119710791175678

Malnar, J. M., Vodvarka, F. (2004). Sensory design. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Marusic, B. G. (2011). Analysis of patterns of spatial occupancy in urban open space using behaviour maps and GIS. Urban Design International, 16(1), 36–50. doi:http://dx.doi.org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1057/udi.2010.20

Moral, J. C. M., Terrero, F. B. F., Galán, A. S., & Rodríguez, T. M. (2015). Effect of integrative reminiscence therapy on depression, well-being, integrity, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in older adults. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936968

Nanda, U., Solovyova, I. (2005). The embodiment of the eye in architectural education. In E. Harder (Ed.). Writings in Architectural Education (pp. 150–164). Copenhagen: EAAE. Retrieved from http://ndl.ethernet.edu.et/bitstream/123456789/47553/1/71.pdf#page=152

O’Rourke, H.M., Collins, L. & Sidani, S. (2018). Interventions to address social connectedness and loneliness for older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatrics, 18, 214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0897-x

Pallasmaa, J. (2005). The eyes of the skin. Chichester: Wiley.

Parker, R. G. (1999). Reminiscence as continuity: Comparison of young and older adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 5(2): 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022931111622

Rokni, D., Murthy, V. N. (2014). Analysis and synthesis in olfaction. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 5(10), 870-872. https://doi.org/10.1021/cn500199n

Simner, J., Mulvenna, C., Sagiv, N., Tsakanikos, E., Witherby, S. A., Fraser, C., Scott, K., & Ward, J. (2006). Synaesthesia: The prevalence of atypical cross-modal experiences. Perception, 35(8), 1024–1033. https://doi.org/10.1068/p5469

Smith, M. (n.d.). Preventing Alzheimer's disease. Retrieved July 8, 2021, from https://www.helpguide.org/articles/alzheimers-dementia-aging/preventing-alzheimers-disease.htm#

Tan, S.-A. (2017, September 2). Call to promote inter-generational bonding to boost elderly's well-being. The Straits Times, Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/children-bring-smiles-to-elderly-faces

Trivic, Z., Tan, B.K., Mascarenhas, N., & Duong, Q. (2020). Capacities and impacts of community arts and culture initiatives in Singapore. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 50(2), 85–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2020.1720877

Trivic, Z. (2021). a study of older adults’ perception of high-density housing neighbourhoods in singapore: multi-sensory perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18: 6880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph18136880

United Nations (UN), Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019: Volume 1: Comprehensive Tables. New York: United Nations. Retrieved July 8, 2021, from https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Volume-I_Comprehensive-Tables.pdf

Whyte, W. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Washington: The Conservation Foundation.

World Health Organization. (2017, December 12). Mental health of older adults. Retrieved July 8, 2021, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults

Yuen, B., & Nair, P. (2019). Investigating space, activities and social dynamics. In B. Yuen (Ed.), Ageing and the built environment in Singapore (pp. 175–219). Cham: Springer.

Zardini, M. (2005). Toward a sensorial urbanism. In M. Zardini (Ed.). Sense of the city: An alternate approach to urbanism (pp. 17–27). Baden: Lars Müller Publishers; Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture.