Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2021:7;5

RESEARCH

A Comparative Analysis of Selected Mental Health Disorders Among Older Residents of Suburbs Versus Neighborhoods

Hamid Iravani (1), Mina Moghtaderi, PhD (2), and Rana Romina Iravani (3)

(1) PARSONS, Transportation Planning Director, Fellows Board Member, Dubai, UAE

*Corresponding author: [email protected]

(2) Health Psychologist, Dubai, UAE

(3) Psychology Student, New York University, New York, USA

(1) PARSONS, Transportation Planning Director, Fellows Board Member, Dubai, UAE

*Corresponding author: [email protected]

(2) Health Psychologist, Dubai, UAE

(3) Psychology Student, New York University, New York, USA

Citation: Iravani H, Moghtaderi M, Iravani RR (2021). A comparative analysis of selected mental health disorders among older residents of suburbs versus neighborhoods. Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 7;15

Abstract

The urban fabric of traditional neighborhoods is compact and pedestrian friendly and features mixed land use, while contemporary conventional suburban developments are low density and auto oriented with segregated land use. Two hundred older residents, one hundred living in traditional neighborhoods and one hundred living in conventional suburbs, were surveyed. Customized questionnaires were used to measure four variables, including the level of 1) somatic symptoms, 2) anxiety/insomnia, 3) social dysfunction, and 4) severe depression. Central tendency measures, standard deviation, and multivariate tests were applied to compare the four variables in both groups. The result revealed that a traditional neighborhood setting has a greater sense of community and therefore positive impacts on its residents as it relates to somatic symptoms and social dysfunction compared to conventional suburbs. Further assessment in this study explored the higher level social interaction of residents in traditional neighborhoods due to community design and how it relates to a higher level of psychological health.

Introduction

The aim of this study is to measure the level of selected mental health disorders, including somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression, among older residents of conventional suburbs (subsequently referred to as suburbs) and compare it to that of residents of traditional neighborhoods (subsequently referred to as neighborhoods). This objective is pursued through a special survey of older respondents living in two suburbs and those living in a neighborhood. To respect the privacy of each area, the names of the two suburbs and the neighborhood will remain anonymous, but an example of a neighborhood street and an example of a suburb street are shown in Figure 1. The urban fabric of neighborhoods is not only associated with mixed land use; rather, in addition to mixed use, neighborhoods share several features and characteristics, as presented in Figure 2 and compared with suburbs.

Figure 1 – An Example of a Street in a Neighborhood in Barcelona, Spain (Left). An Example of a Street in a Suburb in San Jose, California, USA (Right).

Variable |

Suburb |

Neighbourhood |

Land Use Population Density Building Setback Mode of Transportation Roadway Layout Street Width Intersections Parking |

Segregated Low Large Auto Oriented Dendritic Wide Large, Some Grade Separated Off-Street |

Mixed Medium to High Zero to Narrow Mostly Walk and Transit Interconnected Grid Narrow Small Mostly On-Street |

Figure 2 - Urban Characteristics of Suburbs Versus Neighborhoods

A number of studies have explored the relationship between the built environment and physical health, but fewer have examined its relationship with mental health, especially as it relates to older people. The salutary effect of more compact areas on obesity are among those studies (Ewing, et al, 2014). The positive impact of land use mix and distance walked have been assessed as effective measures regarding obesity (Frank, et al, 2004). The association of modal diversity with health outcomes, such as high obesity and chronic diseases related to physical inactivity, have also been assessed (Fredrick, et al, 2017). Another study determined that higher-density neighborhoods also have positive health impacts because residents undertake more walking and physical activity, whereas low-density suburbs result in increased rates of overweight and obese adults and adolescents, but this relationship is less clear in younger children (Giles-Corti, et al, 2014).

The ten New Urbanism principles have been proven to positively affect public health due to the higher usage of non-motorized and public transit, resulting in more physical activity; the lower usage of private automobiles, causing less air pollution and safer streets with fewer traffic accidents; and complete community planning for residents, producing better access to health resources for all residents (Iravani and Rao, 2020). Those ten New Urbanism principles include walkability, connectivity, mixed use and diversity, mixed housing, quality architecture and urban design, traditional neighborhood structure, increased density, smart transportation, sustainability, and quality of life.

New urbanism principles align with a concept referred to as ‘Mind the GAPS’ (green place, active place, pro-social place, and safe place) by McCay (2017). These four design elements promote better mental health and wellbeing, as Layla McCay describes below.

Green space and the use of street trees that are conveniently accessible by a diverse city population have been linked with a reduction of depression and stress as well as improved social and cognitive functioning (including for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD). Green space encourages exercise and social interactions, which both promote good mental health.

Activity is one of the most important design opportunities for mental health, as it is considered an anti-depressant that can positively affect mild and moderate depression; reduce stress and anxiety; and help alleviate some of the symptoms associated with ADHD, dementia, and even schizophrenia. Safe and convenient non-motorized transportation modes, including walking and cycling, will not only promote exercise but also reduce stressful, sedentary commutes to further promote good mental health.

The existence of pro-social places where people can interact and socialize is considered a key opportunity to promote mental health. Public spaces; street furniture; the orientation of entrances; and the avoidance of long, repetitive building facades that block place connections are elements supported by New Urbanism to promote the use of active transportation while encouraging interactions among people.

Safety and security are also important elements that affect people’s mental health. In an urban area, constant low-level threats can affect mood and stress in the long term. As Mc Cay (2017) states, “Relevant urban dangers can include risks posed by other people (such as being robbed), risks from traffic (such as being run over), and the risk of getting lost (particularly pertinent for those with dementia, where this risk can limit their independence and thus their quality of life). The appropriate design of roads, good street lighting, and distinct landmarks and wayfinding cues are just some of the design features that can increase perceptions of safety in a neighborhood.”

Clearly, one who explores the correlation between health and urban form must define one’s interpretation of health, as different perceptions can lead to different conclusions. According to the World Health Organization (1994), health is defined as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief or economic and social condition.” This statement makes it evident that the concept of health has changed from medical model towards a social model (Duhl and Sanchez, 1999). The former focuses mainly on the individual and the treatment of diseases, whereas the latter identifies health as an outcome of socioeconomic status, culture, environmental conditions, housing, employment, and community influences. Therefore, the significant influence of the physical environment on physical and mental health has gained much attention in recent years.

The recent movement in urban planning known as New Urbanism and the similar concept of Neo-Traditional Planning respond to issues faced as the result of the adverse impact of automobiles on society, economy, and health. The key principals of New Urbanism, as documented by the Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Development (1999), are pedestrian-centered neighborhoods where economic and social activities are within a five-minute walk, community orientation around public transport systems, and mixed land use. Such concepts promote a higher level of physical activity and offer residents more opportunity to live, work, and play in their community and, therefore, more socialization. All these attributes create positive impacts on physical and psychological health. Peter Calthorpe (1995), one of the founders of New Urbanism, advocates linking investment in inner-city redevelopment to regional opportunities rather than those isolated or contained within small geographic boundaries. The focus of people-oriented concepts, such as New Urbanism or Neo-Traditional Planning, as opposed to auto-oriented concepts, is to return to the grid patterns and walkable streets of the traditional developments of the era before World War II and adapt them to the needs of today. An example of how such a concept can apply to a modern city street is shown in Figure 3.

The ten New Urbanism principles have been proven to positively affect public health due to the higher usage of non-motorized and public transit, resulting in more physical activity; the lower usage of private automobiles, causing less air pollution and safer streets with fewer traffic accidents; and complete community planning for residents, producing better access to health resources for all residents (Iravani and Rao, 2020). Those ten New Urbanism principles include walkability, connectivity, mixed use and diversity, mixed housing, quality architecture and urban design, traditional neighborhood structure, increased density, smart transportation, sustainability, and quality of life.

New urbanism principles align with a concept referred to as ‘Mind the GAPS’ (green place, active place, pro-social place, and safe place) by McCay (2017). These four design elements promote better mental health and wellbeing, as Layla McCay describes below.

Green space and the use of street trees that are conveniently accessible by a diverse city population have been linked with a reduction of depression and stress as well as improved social and cognitive functioning (including for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD). Green space encourages exercise and social interactions, which both promote good mental health.

Activity is one of the most important design opportunities for mental health, as it is considered an anti-depressant that can positively affect mild and moderate depression; reduce stress and anxiety; and help alleviate some of the symptoms associated with ADHD, dementia, and even schizophrenia. Safe and convenient non-motorized transportation modes, including walking and cycling, will not only promote exercise but also reduce stressful, sedentary commutes to further promote good mental health.

The existence of pro-social places where people can interact and socialize is considered a key opportunity to promote mental health. Public spaces; street furniture; the orientation of entrances; and the avoidance of long, repetitive building facades that block place connections are elements supported by New Urbanism to promote the use of active transportation while encouraging interactions among people.

Safety and security are also important elements that affect people’s mental health. In an urban area, constant low-level threats can affect mood and stress in the long term. As Mc Cay (2017) states, “Relevant urban dangers can include risks posed by other people (such as being robbed), risks from traffic (such as being run over), and the risk of getting lost (particularly pertinent for those with dementia, where this risk can limit their independence and thus their quality of life). The appropriate design of roads, good street lighting, and distinct landmarks and wayfinding cues are just some of the design features that can increase perceptions of safety in a neighborhood.”

Clearly, one who explores the correlation between health and urban form must define one’s interpretation of health, as different perceptions can lead to different conclusions. According to the World Health Organization (1994), health is defined as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief or economic and social condition.” This statement makes it evident that the concept of health has changed from medical model towards a social model (Duhl and Sanchez, 1999). The former focuses mainly on the individual and the treatment of diseases, whereas the latter identifies health as an outcome of socioeconomic status, culture, environmental conditions, housing, employment, and community influences. Therefore, the significant influence of the physical environment on physical and mental health has gained much attention in recent years.

The recent movement in urban planning known as New Urbanism and the similar concept of Neo-Traditional Planning respond to issues faced as the result of the adverse impact of automobiles on society, economy, and health. The key principals of New Urbanism, as documented by the Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Development (1999), are pedestrian-centered neighborhoods where economic and social activities are within a five-minute walk, community orientation around public transport systems, and mixed land use. Such concepts promote a higher level of physical activity and offer residents more opportunity to live, work, and play in their community and, therefore, more socialization. All these attributes create positive impacts on physical and psychological health. Peter Calthorpe (1995), one of the founders of New Urbanism, advocates linking investment in inner-city redevelopment to regional opportunities rather than those isolated or contained within small geographic boundaries. The focus of people-oriented concepts, such as New Urbanism or Neo-Traditional Planning, as opposed to auto-oriented concepts, is to return to the grid patterns and walkable streets of the traditional developments of the era before World War II and adapt them to the needs of today. An example of how such a concept can apply to a modern city street is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – A Boulevard Rendering Showing Features of a Neighborhood by Emphasizing Transit, Pedestrians, Cyclists, Street Trees and Furniture, Mixed Land Use, Store Fronts, and More Space for Public Real

The aforementioned concepts require more investigation of the link between a place’s physical features and public health, particularly psychological health. In a study Dimitris (2013) points out the emergence of the new “Science of Happiness,” which explores measures of subjective happiness and the variables affecting it. There has been very little research in urban and regional studies in this emerging interdisciplinary field, but it is very much recognized that the links between spatial factors, particularly those of cities and regions, that affect subjective happiness and well-being should be measured.

Despite the rare research work that has been conducted to relate somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression with urban form, one can detect such relationships indirectly. In other words, there are many studies that relate the positive impact of physical activities with these psychological variables, and there is much research revealing that urban areas characterized by a traditional urban fabric are more pedestrian friendly and therefore walkable, so linking these correlations to the effect of neighborhoods versus suburbs on somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression is a natural next step. Moreover, due to the higher number of social interactions available in neighborhoods, residents are less alienated and hence less depressed. An important study conducted by Mayo Clinic staff (2014) concluded that regular exercise probably helps ease depression in a number of ways, which may include releasing feel-good brain chemicals, reducing immune system chemicals, and increasing body temperature. Also, regular exercise has many psychological and emotional benefits, including increasing confidence, reducing worry, enhancing social interaction, and improving healthy coping. All these can be affected by more walking, which does not occur as often in low-density, auto-oriented, far-flung suburbs.

In addition to the above secondary resources, a more direct analysis was also conducted in this research to explore the direct relationship between urban form and the variables described, particularly for the older population.

Despite the rare research work that has been conducted to relate somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression with urban form, one can detect such relationships indirectly. In other words, there are many studies that relate the positive impact of physical activities with these psychological variables, and there is much research revealing that urban areas characterized by a traditional urban fabric are more pedestrian friendly and therefore walkable, so linking these correlations to the effect of neighborhoods versus suburbs on somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression is a natural next step. Moreover, due to the higher number of social interactions available in neighborhoods, residents are less alienated and hence less depressed. An important study conducted by Mayo Clinic staff (2014) concluded that regular exercise probably helps ease depression in a number of ways, which may include releasing feel-good brain chemicals, reducing immune system chemicals, and increasing body temperature. Also, regular exercise has many psychological and emotional benefits, including increasing confidence, reducing worry, enhancing social interaction, and improving healthy coping. All these can be affected by more walking, which does not occur as often in low-density, auto-oriented, far-flung suburbs.

In addition to the above secondary resources, a more direct analysis was also conducted in this research to explore the direct relationship between urban form and the variables described, particularly for the older population.

Methodology

This research was implemented with the objective of comparing the level of somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression among two groups of older residents, with a minimum age of sixty-five years, who all used to work as teachers in public schools. The two groups of residents consisted of those living in urban areas with neighborhood characteristics and the those living in low-density suburbs. The total sample size for the survey conducted for this study was 200 residents, with 100 questionnaires answered by each group. These two groups were approached in a public park at a special event for retired citizens who worked as teachers in public schools. They were given instructions in groups, then questionnaires were distributed, and they filled out the questionnaires at the same time. Initially the number of respondents were more than 200; however, responses by the older people living in suburbs and were separated from those living in the neighborhood, and a few randomly selected questionnaires belonging to the neighborhood group were discarded to ensure each group was represented by 100 responses. Considering that the event related to a teachers’ retirement fund for teachers who all worked in the public sector, the socio-economic status of the respondents were generally in the same range.

The independent variable in this survey is the type of urban fabric, which could be either neighborhood or suburb, and the dependent variables are somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression among older residents.

The selection of the retired teachers interviewed, whose general socio-economic status were approximately in the same range, is important because the independent variables tested in this study should not be influenced by other variables, although the specific data for the socio-economic characteristics, particularly income, were not allowed be collected. There are numerous studies revealing that many social stressors could affect mental health and disorders. Silvia, Loureiro, and Cardoso (2016), in describing the social determinants of mental health, conclude that mental health is the complex outcome of biological, psychological, and social factors. Social disadvantages, including low income and limited education and employment, are among the variables. Lack of social support, high demand or low control over work, critical life events, unemployment, adverse neighborhood characteristics, and income inequality are identified as psychosocial risks that increase the chances of poor mental health.

Research instrument

Following the explanation of the importance of the survey and its objectives to the respondents, General Health Questionnaire – 28 (GHQ-28), which is the short version of the actual questionnaire and includes 28 questions developed by Goldberg (1978), was distributed among the older residents of neighborhoods and the older residents of the suburbs. GHQ-28 is considered a screening tool to detect those likely to have or possibly at risk of developing psychiatric disorders (Sterling, 2011). The GHQ-28 is categorized into four subscales. These are somatic symptoms (items 1–7), anxiety/insomnia (items 8–14), social dysfunction (items 15–21), and severe depression (items 22–28).

Some of the queries in the questionnaire include “Have you found everything getting on top of you? ” “Have you been getting scared or panicky for no good reason?,” and “Have you been getting edgy and bad tempered?” Each item consists of four possible responses: “Not at all,” “No more than usual,” “Rather more than usual,” and “Much more than usual.” There are different methods to score the GHQ-28. Responses were coded and scored from 0 to 3, with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 84. Furthermore, additional questions were added to the questionnaire, including age, place, and type of residence, to distinguish those living in neighborhoods from those in suburbs.

Several studies have evaluated the reliability and validity of the GHQ-28 in different clinical populations. The level of reliability has been reported to be high, ranging from 0.78 to 0.9 (Robinson and Price 1982). Interrater and intrarater reliability have also both proven to be excellent, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.9 to 0.95, and high internal consistency has also been reported (Failde and Ramos 2000). The GHQ-28 correlates well with the Hospital Depression and Anxiety Scale (HADS) (Sakakibara et al. 2009) and other measures of depression (Robinson and Price 1982).

The reliability and validity of GHQ has been also evaluated by different methods. Among them is a measure of internal consistency performed by Bahmani and Asgari (2006), represented by the Cronbach's alpha, with results for somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression being 0.85, 0.8, 0.79, and 0.91, respectively. The Cronbach's alpha for the overall instrument is 0.85. Furthermore, for this survey Cronbach's alpha was measured, and the result was 0.77, indicating a high level of internal consistency among the scales reported.

The independent variable in this survey is the type of urban fabric, which could be either neighborhood or suburb, and the dependent variables are somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression among older residents.

The selection of the retired teachers interviewed, whose general socio-economic status were approximately in the same range, is important because the independent variables tested in this study should not be influenced by other variables, although the specific data for the socio-economic characteristics, particularly income, were not allowed be collected. There are numerous studies revealing that many social stressors could affect mental health and disorders. Silvia, Loureiro, and Cardoso (2016), in describing the social determinants of mental health, conclude that mental health is the complex outcome of biological, psychological, and social factors. Social disadvantages, including low income and limited education and employment, are among the variables. Lack of social support, high demand or low control over work, critical life events, unemployment, adverse neighborhood characteristics, and income inequality are identified as psychosocial risks that increase the chances of poor mental health.

Research instrument

Following the explanation of the importance of the survey and its objectives to the respondents, General Health Questionnaire – 28 (GHQ-28), which is the short version of the actual questionnaire and includes 28 questions developed by Goldberg (1978), was distributed among the older residents of neighborhoods and the older residents of the suburbs. GHQ-28 is considered a screening tool to detect those likely to have or possibly at risk of developing psychiatric disorders (Sterling, 2011). The GHQ-28 is categorized into four subscales. These are somatic symptoms (items 1–7), anxiety/insomnia (items 8–14), social dysfunction (items 15–21), and severe depression (items 22–28).

Some of the queries in the questionnaire include “Have you found everything getting on top of you? ” “Have you been getting scared or panicky for no good reason?,” and “Have you been getting edgy and bad tempered?” Each item consists of four possible responses: “Not at all,” “No more than usual,” “Rather more than usual,” and “Much more than usual.” There are different methods to score the GHQ-28. Responses were coded and scored from 0 to 3, with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 84. Furthermore, additional questions were added to the questionnaire, including age, place, and type of residence, to distinguish those living in neighborhoods from those in suburbs.

Several studies have evaluated the reliability and validity of the GHQ-28 in different clinical populations. The level of reliability has been reported to be high, ranging from 0.78 to 0.9 (Robinson and Price 1982). Interrater and intrarater reliability have also both proven to be excellent, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.9 to 0.95, and high internal consistency has also been reported (Failde and Ramos 2000). The GHQ-28 correlates well with the Hospital Depression and Anxiety Scale (HADS) (Sakakibara et al. 2009) and other measures of depression (Robinson and Price 1982).

The reliability and validity of GHQ has been also evaluated by different methods. Among them is a measure of internal consistency performed by Bahmani and Asgari (2006), represented by the Cronbach's alpha, with results for somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression being 0.85, 0.8, 0.79, and 0.91, respectively. The Cronbach's alpha for the overall instrument is 0.85. Furthermore, for this survey Cronbach's alpha was measured, and the result was 0.77, indicating a high level of internal consistency among the scales reported.

Results

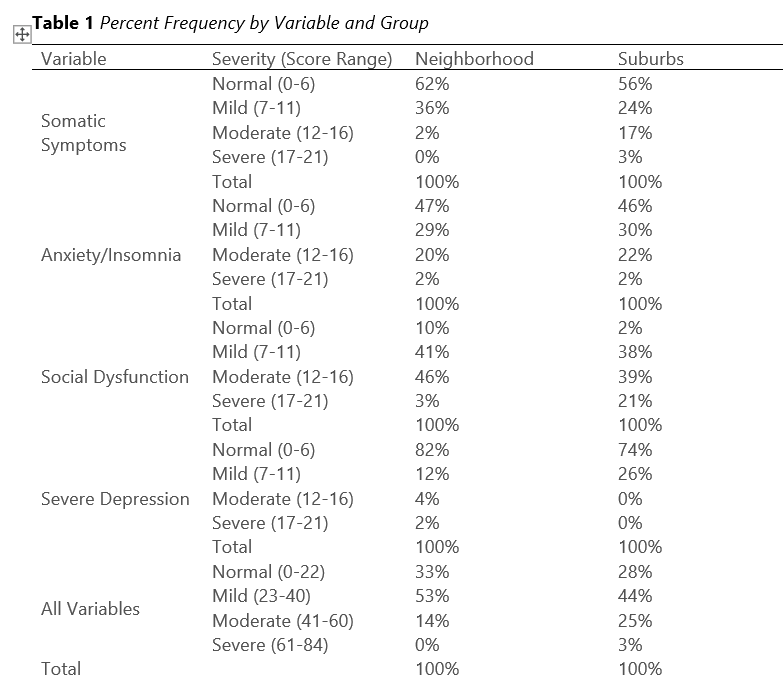

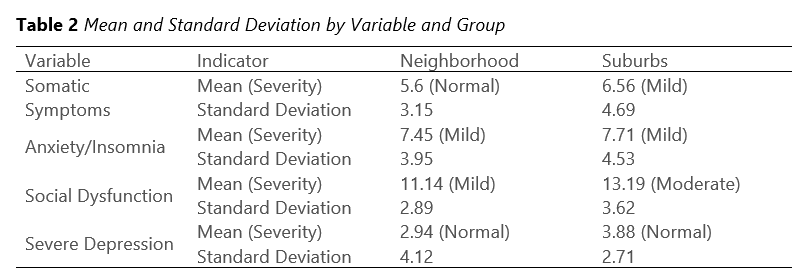

The summary result of the survey is presented in Table 2. In this table the severity of each variable, including the levels of somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression, is identified by the older residents living in low-density suburbs and those living in neighborhoods. The severity ratings were subdivided into “Normal,” “Mild,” “Moderate,” and “Severe” based on thresholds defined by Goldberg (1978). The result clearly reveals that residents who live in neighborhoods have lower levels of somatic symptoms and social dysfunction compared to the group who live in low-density suburbs. Moreover, in this research other central tendency measures, including mean, standard deviation from the mean, and multivariate tests, for the same variables and by the two groups were measured and reported in Table 3. This result also shows that older residents of suburbs suffer from a mild level of somatic symptoms and a moderate level of social dysfunction, which are worse conditions than those older persons living in neighborhoods.

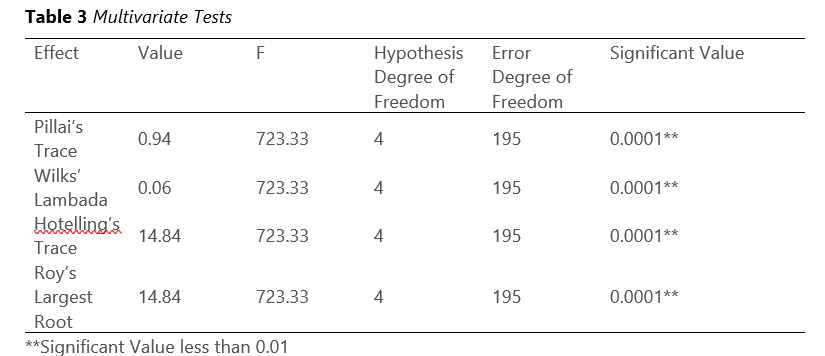

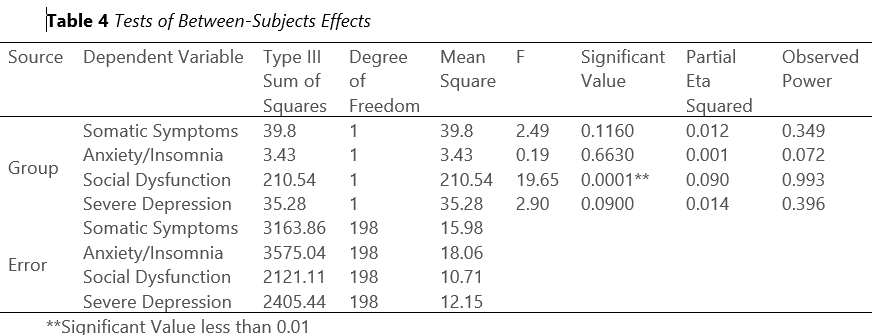

Moreover, multivariate tests, as presented in Table 4, were also performed, and the result indicates that at least one of the variables, including somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression, differs between the two groups of older residents. To signify such difference, tests of between-subjects effects were conducted. The result, presented in Table 4, shows that among the four variables, social dysfunction had significant value of less than 0.01.

Sense of community is often described as the main value of Neo-Traditional Development or New Urbanism (Audirac, 1999; “Bye-Bye Suburban Dream,” 1995; Kelbaugh, 1997). Enhancing individual and community well-being can be achieved by “psychological sense of community” (Nelson and Prilleltensky, 2005). Hence, the main cause for the adverse psychological impacts of living in suburbs evaluated in this study can be linked to the lack of sense of community. A comparative analysis study conducted by Joonngsub and Rachel (2004) between a neo-traditional community and a suburban development concluded that the former perceive a substantially greater sense of community; and residents have a stronger attachment to their place and express a sense of identity with it. Natural features and open spaces which promote walkability and increase social interactions are imperative. The overall community layout and traditional architectural style play vital functions in achieving sense of community. Moreover, pedestrian friendly developments which result social connectedness promote physical and mental health for residents and in particular for the older population (Berke, Gottlieb et al. 2007).

Neo-traditional developments feature narrower roads in a grid network framework, more curves, on-street parking as a buffer between moving traffic and pedestrians, and slower speed limits. Mixed land use, storefront shops, and recreational destinations are accessible within walking distance. These human scale features enhance sense of community and improves both physical and psychological well-being. These elements provide comfort and safety of older pedestrians, and also address safety needs of older drivers, who suffer from loss of depth perception. These elements usually exist in most traditional and neo-traditional communities in the United States. Many of these communities emerged naturally and address the mobility needs of most Americans effectively. It is worth noting many of these communities developed prior to the advent of the personal automobile and continue to perform better than conventional development in terms of health, safety, and mobility (Kerr and Frank, 2012).

Moreover, multivariate tests, as presented in Table 4, were also performed, and the result indicates that at least one of the variables, including somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression, differs between the two groups of older residents. To signify such difference, tests of between-subjects effects were conducted. The result, presented in Table 4, shows that among the four variables, social dysfunction had significant value of less than 0.01.

Sense of community is often described as the main value of Neo-Traditional Development or New Urbanism (Audirac, 1999; “Bye-Bye Suburban Dream,” 1995; Kelbaugh, 1997). Enhancing individual and community well-being can be achieved by “psychological sense of community” (Nelson and Prilleltensky, 2005). Hence, the main cause for the adverse psychological impacts of living in suburbs evaluated in this study can be linked to the lack of sense of community. A comparative analysis study conducted by Joonngsub and Rachel (2004) between a neo-traditional community and a suburban development concluded that the former perceive a substantially greater sense of community; and residents have a stronger attachment to their place and express a sense of identity with it. Natural features and open spaces which promote walkability and increase social interactions are imperative. The overall community layout and traditional architectural style play vital functions in achieving sense of community. Moreover, pedestrian friendly developments which result social connectedness promote physical and mental health for residents and in particular for the older population (Berke, Gottlieb et al. 2007).

Neo-traditional developments feature narrower roads in a grid network framework, more curves, on-street parking as a buffer between moving traffic and pedestrians, and slower speed limits. Mixed land use, storefront shops, and recreational destinations are accessible within walking distance. These human scale features enhance sense of community and improves both physical and psychological well-being. These elements provide comfort and safety of older pedestrians, and also address safety needs of older drivers, who suffer from loss of depth perception. These elements usually exist in most traditional and neo-traditional communities in the United States. Many of these communities emerged naturally and address the mobility needs of most Americans effectively. It is worth noting many of these communities developed prior to the advent of the personal automobile and continue to perform better than conventional development in terms of health, safety, and mobility (Kerr and Frank, 2012).

Conclusion

The results of the specific survey conducted in this study reveal that neighborhoods have a positive impact on somatic symptoms and social dysfunction. Linking these together, one may conclude that neighborhoods are more pedestrian friendly as opposed to the auto-oriented low-density suburbs and that neighborhoods encourage mixed land use and closeness of neighbors, generating a higher level of social interaction among the residents, and that all these factors contribute to a higher level of psychological health among the people living in communities with traditional urban fabric.

The limitation of this study relates to analyzing urban form as the main determinant for these older people’s mental health condition, whereas many variables could impact and influence mental health. Further research is suggested to explore whether the mental health condition of older residents in neighborhoods differs from that of those in suburbs because of the impact of urban form and to examine how urban design affects their condition in comparison to their socio-economic characteristics. Moreover, as discussed in this study, urban form in neighborhoods positively influences the mental health of older people, but not as a direct cause. In other words, urban form in neighborhoods, as opposed to suburbs, causes older people to be more active, rely less on automobile use, and socialize, thereby having indirect impacts. A path analysis, which is a statistical method to describe the direct dependencies among a set of variables that potentially could affect the mental health of older people, is suggested as further research on this subject.

The limitation of this study relates to analyzing urban form as the main determinant for these older people’s mental health condition, whereas many variables could impact and influence mental health. Further research is suggested to explore whether the mental health condition of older residents in neighborhoods differs from that of those in suburbs because of the impact of urban form and to examine how urban design affects their condition in comparison to their socio-economic characteristics. Moreover, as discussed in this study, urban form in neighborhoods positively influences the mental health of older people, but not as a direct cause. In other words, urban form in neighborhoods, as opposed to suburbs, causes older people to be more active, rely less on automobile use, and socialize, thereby having indirect impacts. A path analysis, which is a statistical method to describe the direct dependencies among a set of variables that potentially could affect the mental health of older people, is suggested as further research on this subject.

About the Authors

|

Hamid Iravani is Parsons’ transportation planning director and a Parsons Technical Fellows board member based in Dubai, UAE. He has more than 30 years of experience in strategic multimodal travel demand forecast model development, traffic engineering, routing, database management, and the linkage between land use and transportation. He has developed innovative solutions, such as an intersection delay function algorithm that is part of TransCAD Transportation Planning Software under his name and a computer program for Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis using different alternative evaluation methodologies. During his undergraduate studies, he double-majored in psychology and urban studies, ultimately receiving a bachelor’s degree and a certificate, respectively. He also holds a Master of Urban Planning from Portland State University with a specialty in urban design. Contact him via LinkedIn.

|

References

Audirac, I. (1999). Stated preference for pedestrian proximity: An assessment of new urbanist sense of community. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 19, 53-66.

Asgari, A., and Bahmani, B., (2006). The national standardization and evaluation of the psychometric indices of GHQ for the medical students. Publication collection of the Third nationwide seminar on the Mental Health of the Students, Iran. May 24-15.

Berke, E.; Gottlieb, L.; Moudon, A. and Larson, E. (2007). ‘‘Protective Association Between Neighborhood Walkability and Depression in Older Men.’’ Journal of American Geriatric Society 55:526–33.

Bye-bye suburban dream: 15 ways to fix the suburbs. (1995, May 15). Newsweek, p. 40

Calthorpe, P. (1995). A new metropolitan strategy, http://www.transact.org/nov95/anew.htm (retrieved in April 1999).

Center of Excellence for Sustainable Development. Key planning principles: new urbanism/neo-traditional planning. http://www.sustainable.doe.gov/landuse/lunewurb.htm (retrieved in April 1999).

Dimitris, B. (2013). What makes a ‘happy city’? Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Cities 32, S39–S50.

Duhl, L.J., and Sanchez, A.K. (1999). Healthy Cities and City Planning Process. A Background Document on Links between Health and Urban Planning. European Health21 Target 13, 14.

Ewing, R.; Meakins G.; Hamidi S.; and Nelson A. (2014). “Relationship between Urban Sprawl and Physical Activity, Obesity, and Morbidity – Update and Refinement.” Health & Place 26: 118–126. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.12.008.

Frank, D.; Andresen A.; and Schmid L. (2004). “Obesity Relationships with Community Design, Physical Activity, and Time Spent in Cars.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 27 (2): 87–96. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.011.

Failde, I.; Ramos, I.; and Fernandez-Palacín, F. Comparison between the GHQ-28 and SF-36 (MH 1–5) for the assessment of the mental health in patients with ischaemic heart disease. Eur J Epidemiol 16, 311–316 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007688525023

Frederick, C.; Riggs W.; and Gilderbloom J. (2017). “Commute Mode Diversity and Public Health: A Multivariate Analysis of 148 US Cities.” International Journal of Sustainable Transportation V12 (1): 1–11.

Giles-Corti, B.; Hooper P.; Foster S.; Koohsari M.; and Francis J. (2014). Low Density Development: Impacts on Physical Activity and Associated Health Outcomes. Heart Foundation. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/FINAL_Heart_Foundation_Low_density_Report_September_2014.pdf

Goldberg, D. (1978). Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson.

Iravani, H., and Rao, V. (2020). The effects of New Urbanism on public health, Journal of Urban Design, 25:2, 218 235, DOI: 10.1080/13574809.2018.1554997

Joongsub, K. and Rachel, K. (2004). “Physical and Psychological Factors in Sense of Community New Urbanist Kentlands and Nearby Orchard Village.” Environment and Behavior, Vol. 36 No. 3, (May 2004) 313-340 DOI: 10.1177/0013916503260236

Kelbaugh, D. (1997). Commonplace: Toward neighborhood and regional design. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Kerr, J.; Rosenberg, D and Frank, L. The Role of the Built Environment in Healthy Aging: Community Design, Physical Activity, and Health among Older Adults. Journal of Planning Literature 2012 27: 43 originally published online 17 January 2012. DOI: 10.1177/0885412211415283.

McCay, L (2017). Designing Mental Health into Cities, Urban Design Group Journal, No. 142, Spring 2017. https://www.udg.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/UD142_magazine%20Health%20and%20Urban%20Design.pdf

Mayo Clinic Staff (2014). Depression (major depressive disorder). http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/depression-and-exercise/art-20046495

Nelson, G. and Prilleltensky, I. (2005) Community Psychology: In Pursuit of Liberation and Well-Being. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Robinson, R.G., and Price, T.R. Post-stroke depressive disorders: a follow-up study of 103 patients. Stroke. (1982 Sep-Oct); 13(5): 635-41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.13.5.635. PMID: 7123596.

Sakakibara, B.M.; Miller, W.C.; Orenczuk, S.G.; Wolfe, D.L.; SCIRE Research Team (2009). A systematic review of depression and anxiety measures used with individuals with spinal cord injury. Dec;47(12):841-51. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.93.

Silvia, M.; Loureiro, A. and Grace, C (2016). Social Determinants of Mental Health. European Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 30, N. 4, (259-292)

Sterling, Michele (2011). General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28). Journal of Physiotherapy 57(4):259. DOI: 10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70060-1

World Health Organization (1994). Constitution of the World Health Organization. In: WHO basic documents, 40th ed. Geneva, World Health Organization.

Asgari, A., and Bahmani, B., (2006). The national standardization and evaluation of the psychometric indices of GHQ for the medical students. Publication collection of the Third nationwide seminar on the Mental Health of the Students, Iran. May 24-15.

Berke, E.; Gottlieb, L.; Moudon, A. and Larson, E. (2007). ‘‘Protective Association Between Neighborhood Walkability and Depression in Older Men.’’ Journal of American Geriatric Society 55:526–33.

Bye-bye suburban dream: 15 ways to fix the suburbs. (1995, May 15). Newsweek, p. 40

Calthorpe, P. (1995). A new metropolitan strategy, http://www.transact.org/nov95/anew.htm (retrieved in April 1999).

Center of Excellence for Sustainable Development. Key planning principles: new urbanism/neo-traditional planning. http://www.sustainable.doe.gov/landuse/lunewurb.htm (retrieved in April 1999).

Dimitris, B. (2013). What makes a ‘happy city’? Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Cities 32, S39–S50.

Duhl, L.J., and Sanchez, A.K. (1999). Healthy Cities and City Planning Process. A Background Document on Links between Health and Urban Planning. European Health21 Target 13, 14.

Ewing, R.; Meakins G.; Hamidi S.; and Nelson A. (2014). “Relationship between Urban Sprawl and Physical Activity, Obesity, and Morbidity – Update and Refinement.” Health & Place 26: 118–126. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.12.008.

Frank, D.; Andresen A.; and Schmid L. (2004). “Obesity Relationships with Community Design, Physical Activity, and Time Spent in Cars.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 27 (2): 87–96. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.011.

Failde, I.; Ramos, I.; and Fernandez-Palacín, F. Comparison between the GHQ-28 and SF-36 (MH 1–5) for the assessment of the mental health in patients with ischaemic heart disease. Eur J Epidemiol 16, 311–316 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007688525023

Frederick, C.; Riggs W.; and Gilderbloom J. (2017). “Commute Mode Diversity and Public Health: A Multivariate Analysis of 148 US Cities.” International Journal of Sustainable Transportation V12 (1): 1–11.

Giles-Corti, B.; Hooper P.; Foster S.; Koohsari M.; and Francis J. (2014). Low Density Development: Impacts on Physical Activity and Associated Health Outcomes. Heart Foundation. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/FINAL_Heart_Foundation_Low_density_Report_September_2014.pdf

Goldberg, D. (1978). Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson.

Iravani, H., and Rao, V. (2020). The effects of New Urbanism on public health, Journal of Urban Design, 25:2, 218 235, DOI: 10.1080/13574809.2018.1554997

Joongsub, K. and Rachel, K. (2004). “Physical and Psychological Factors in Sense of Community New Urbanist Kentlands and Nearby Orchard Village.” Environment and Behavior, Vol. 36 No. 3, (May 2004) 313-340 DOI: 10.1177/0013916503260236

Kelbaugh, D. (1997). Commonplace: Toward neighborhood and regional design. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Kerr, J.; Rosenberg, D and Frank, L. The Role of the Built Environment in Healthy Aging: Community Design, Physical Activity, and Health among Older Adults. Journal of Planning Literature 2012 27: 43 originally published online 17 January 2012. DOI: 10.1177/0885412211415283.

McCay, L (2017). Designing Mental Health into Cities, Urban Design Group Journal, No. 142, Spring 2017. https://www.udg.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/UD142_magazine%20Health%20and%20Urban%20Design.pdf

Mayo Clinic Staff (2014). Depression (major depressive disorder). http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/depression-and-exercise/art-20046495

Nelson, G. and Prilleltensky, I. (2005) Community Psychology: In Pursuit of Liberation and Well-Being. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Robinson, R.G., and Price, T.R. Post-stroke depressive disorders: a follow-up study of 103 patients. Stroke. (1982 Sep-Oct); 13(5): 635-41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.13.5.635. PMID: 7123596.

Sakakibara, B.M.; Miller, W.C.; Orenczuk, S.G.; Wolfe, D.L.; SCIRE Research Team (2009). A systematic review of depression and anxiety measures used with individuals with spinal cord injury. Dec;47(12):841-51. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.93.

Silvia, M.; Loureiro, A. and Grace, C (2016). Social Determinants of Mental Health. European Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 30, N. 4, (259-292)

Sterling, Michele (2011). General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28). Journal of Physiotherapy 57(4):259. DOI: 10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70060-1

World Health Organization (1994). Constitution of the World Health Organization. In: WHO basic documents, 40th ed. Geneva, World Health Organization.