Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2021:7;3

ANALYSIS

How do green spaces prevent cognitive decline? A call for “research-by-design”

Gan, D. R. Y. (1), Zhang, L.(2), Ng, T. K. S.(3)

(1) Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada

(2) School of Design, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China

(3) Department of Psychological Medicine, National University of Singapore

(1) Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada

(2) School of Design, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China

(3) Department of Psychological Medicine, National University of Singapore

Citation: Gan DRY, Zhang L, Ng TKS (2021). How do green spaces prevent cognitive decline? A call for "research-by-design". Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 7;3

Introduction

As global lifespan increases, an increasing number of older adults with dementia are likely to age in community. In North America, this number is as high as 81% of all people with dementia (Lepore et al., 2017, p. 1). The neurobiological processes of dementia is known to start decades prior to a diagnosis (Bateman et al., 2012, Fig. 2). In other words, for every person living with dementia, two more are likely to develop dementia over the next three decades (Prince et al., 2015). As such, the neighborhood has become an important site of prevention. This perspective article provides a brief overview of research from various disciplines to encourage "research-by-design," i.e., design studios at universities with a brief to answer the research question: "How might park design prevent cognitive decline?" Exploratory design could seek to enhance the well-being of people with dementia, their care partners, and general older populations that are at-risk of cognitive decline.

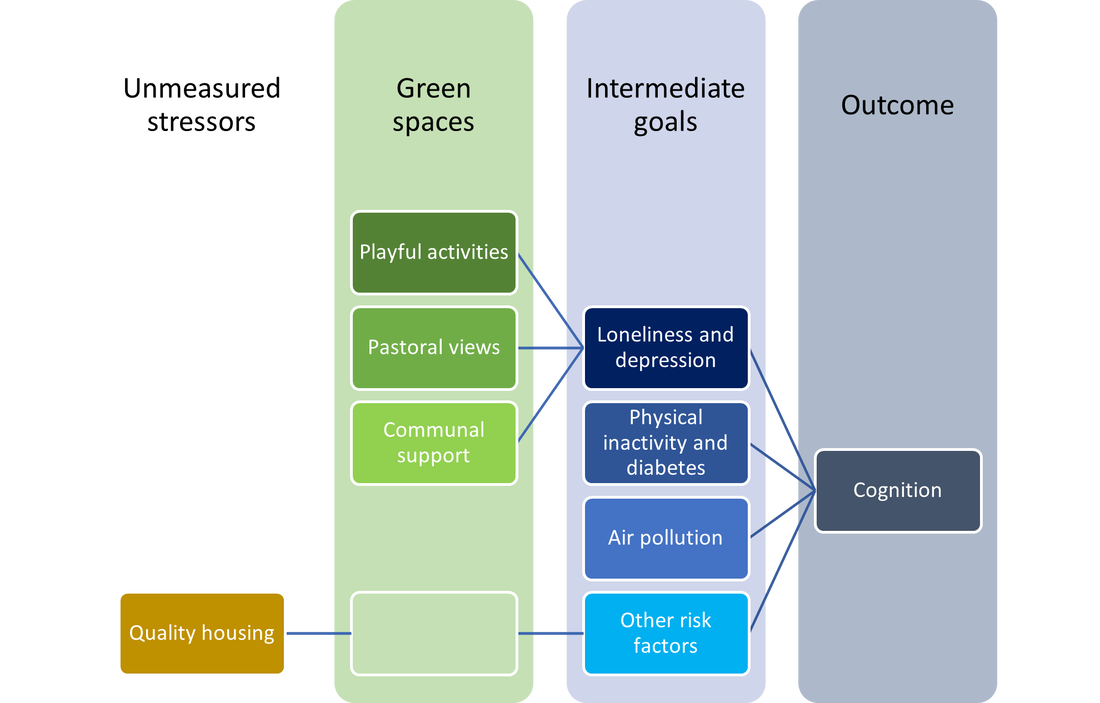

Urban green spaces (UGS) have the potential to improve the well-being of older adults. Health professionals have long recognized the importance of contact with nature (Frumkin, 2001; Pryor et al., 2006). In addition to exercise and social prescriptions, recent innovations include horticultural therapy as complementary medicine (Ng et al., 2018; Maller et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2021). Landscape and urban designers have an opportunity to make neighborhoods more livable for people with dementia, and contribute to reducing 13% of its modifiable risks in late-life, namely loneliness and depression (8%), physical inactivity and diabetes (3%), and air pollution (2%) (Livingston et al., 2020, Fig. 7). These data provide helpful intermediate goals and introduce a “mechanistic” line of inquiry to research-by-design.

“Mechanisms” seek to understand how greenery “get under the skin” to influence cognition. Despite clear evidence in longitudinal studies (e.g., de Keijzer et al., 2018), proof of previously hypothesized mechanisms (Maas et al., 2008; 2009) remain elusive.

This paper aims to synthesize relevant evidences and generate possible mechanisms for research-by-design in community contexts. Given that research-by-design to prevent cognitive decline in community settings is an emerging field, we present here a brief narrative review with selected emphases. Our guiding criteria for selection are as follows: (1) Parsimony. The themes should be sufficiently differentiated to allow specialization while being broad enough to accommodate designers’ creativity and yield different design solutions. (2) Hierarchy. In the absence of clear and empirically validated causal mechanisms, we interrogate theories by referencing longitudinal studies, qualitative synthesis of lived experiences, and laboratory-based experiments, within the current stress-cognition paradigm (Sandi, 2013). (3) Positionality. We recognize that all research studies are conducted within specific contexts, whether disciplinary or personal, and some important perspectives may be underrepresented.

Based on our synthesis, we present the discussions that led to three potential “mechanisms” for research-by-design, under their respective thematic headings:

Pastoral views

Recent critiques of “attention restoration” shed new light on why greenery might affect cognition, which comprise domains of memory, attention, language, visuospatial, and executive abilities for everyday functioning (Jiang et al., 2020; Joye & Dewitte, 2018). It was proposed that effortless attention to natural patterns may relief stress to aid recovery from fatigue (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1983). Instead of assuming that cognition is a depletable resource (like hard disk space), new evidence suggests that cognition is better understood in a flow state (like internet bandwidth), with stress (like background apps) taking up a significant fraction at any one time. Stress could be understood as a source of “cognitive load” and can be measured physiologically (Sandi, 2013; Woody et al., 2018). Excess cognitive load due to personal, social, and/or environmental stress affects mood and cognitive function (Berto, 2014; Jiang et al., 2020).

Many studies have repeatedly shown the cognitive benefits of simply viewing greenery, whether real and potentially accessible, or computer-generated and virtual (Jiang et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2014). In fact, it was a study on post-surgery views of trees vs. brick wall from hospital windows (Ulrich, 1984) which catalyzed on-going studies on green mechanisms to health. Evolutionary perspectives posit a “predisposition to pay attention and respond positively to natural content (e.g., vegetation, water) […] that were favorable to survival” induces positive emotions which alleviate physiological stress (Berto, 2014, p. 396).

Studies have explored the therapeutic qualities of greenery in the lives of older adults, including rural settings (Blackstock et al., 2006; Finlay et al., 2015; Williams, 2010). Views of nature reduce heart rates (Lee & Lee, 2014; South et al., 2015), possibly through a fond memory or a sense of being cared/provided for (Blackstock et al., 2006, p. 170), which distracts or resets (instead of restores) one’s attention away from stressful emotions. Such calming symbolic imaginations have been associated with green landscapes through generations (evident in cultural and planning movements; see Machor, 1987; Ruff, 2015).

At the same time, watching plants bloom, grow, and wither through the seasons could help one reappraise one’s life (Wang & MacMillan, 2013). These natural processes closely resemble the life cycle of a person, from infancy, adolescence, adulthood, to late-life. Observing and caring for plants from afar through these rhythms could instill a larger sense of life and resilience to boost confidence and esteem (Nollman, 1996). The meaning and pleasantness of such views may provide reasons to remain engaged with one’s surroundings, and exercise one’s visuospatial skills.

Communal support

Green spaces are sites of social contact (Cattell et al., 2008). Like other neighborhood third places, green spaces are experienced differently by different persons (Clarke et al., 2012; Korpela et al., 2014). Personal and social experiences may modify its cognitive benefits. More cohesive neighborhoods predicted slower cognitive decline among older adults because of increased engagement in social activities and less anxiety (Sharifian et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2020). Social and emotional support summarize these cross-level cognitive processes (Lee & Waite, 2018), especially in communities with better social atmospheres (Gan et al., 2021c; 2021e).

Older adults are diverse (cf. Forsyth et al., 2019). Multimorbidity increases risk of cognitive decline, especially among men (Vassilaki et al., 2015). Coping with multiple illnesses, which is common for two out of three older North Americans (Barnett et al., 2012; Marengoni et al., 2011), can be challenging and lonely (Coventry et al., 2015; Gan et al., 2021d). For those with greater disease burden, going outdoors to interact is “the best distraction strategy for managing symptoms” (Eckerblad et al., 2020, p. 5).

Social connectedness was central to explaining physiological stress reduction found in horticultural therapies for older adults (Ng et al., 2021). This recent finding supports eco-psychological perspectives of human-nature contact, which is proposed to improve emotions and thus relationship with others (Metzner, 1995; Wilson, 1984). Improved emotional support could address loneliness and depression, which comprise 8% of known dementia risks among older adults (Livingston et al., 2020, Fig. 7).

Playful activities

There is now little doubt that green spaces are important for the well-being of people living with dementia (Hernandez, 2007). Based on a review of 19 studies, Mmako and colleagues (2020) identified ways or “mechanisms” that make green spaces beneficial for the mental well-being of people at various stages of dementia, namely social identity, empowerment, and risk-taking (Mmako et al., 2020, pp. 5-7). These may be summarized as “play,” which has been associated with risk-taking (Eberle, 2014). UGS should empower people with dementia to engage in playful risk-taking and regain an identity in a community setting apart from that of a patient (Gan et al., 2021b).

Opportunities to engage in playful activities are important to people living with dementia, and may delay or prevent progression to more severe stages of dementia. They may also provide respite to care partners. Given that people with dementia may feel overly protected and stifled (Mapes, 2017), designs could put care partners at ease while creating space for people with dementia to explore and make decisions. Deducing such studio design briefs from available studies of mechanisms systematically advances dementia-friendly urban design.

Urban green spaces (UGS) have the potential to improve the well-being of older adults. Health professionals have long recognized the importance of contact with nature (Frumkin, 2001; Pryor et al., 2006). In addition to exercise and social prescriptions, recent innovations include horticultural therapy as complementary medicine (Ng et al., 2018; Maller et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2021). Landscape and urban designers have an opportunity to make neighborhoods more livable for people with dementia, and contribute to reducing 13% of its modifiable risks in late-life, namely loneliness and depression (8%), physical inactivity and diabetes (3%), and air pollution (2%) (Livingston et al., 2020, Fig. 7). These data provide helpful intermediate goals and introduce a “mechanistic” line of inquiry to research-by-design.

“Mechanisms” seek to understand how greenery “get under the skin” to influence cognition. Despite clear evidence in longitudinal studies (e.g., de Keijzer et al., 2018), proof of previously hypothesized mechanisms (Maas et al., 2008; 2009) remain elusive.

This paper aims to synthesize relevant evidences and generate possible mechanisms for research-by-design in community contexts. Given that research-by-design to prevent cognitive decline in community settings is an emerging field, we present here a brief narrative review with selected emphases. Our guiding criteria for selection are as follows: (1) Parsimony. The themes should be sufficiently differentiated to allow specialization while being broad enough to accommodate designers’ creativity and yield different design solutions. (2) Hierarchy. In the absence of clear and empirically validated causal mechanisms, we interrogate theories by referencing longitudinal studies, qualitative synthesis of lived experiences, and laboratory-based experiments, within the current stress-cognition paradigm (Sandi, 2013). (3) Positionality. We recognize that all research studies are conducted within specific contexts, whether disciplinary or personal, and some important perspectives may be underrepresented.

Based on our synthesis, we present the discussions that led to three potential “mechanisms” for research-by-design, under their respective thematic headings:

Pastoral views

Recent critiques of “attention restoration” shed new light on why greenery might affect cognition, which comprise domains of memory, attention, language, visuospatial, and executive abilities for everyday functioning (Jiang et al., 2020; Joye & Dewitte, 2018). It was proposed that effortless attention to natural patterns may relief stress to aid recovery from fatigue (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1983). Instead of assuming that cognition is a depletable resource (like hard disk space), new evidence suggests that cognition is better understood in a flow state (like internet bandwidth), with stress (like background apps) taking up a significant fraction at any one time. Stress could be understood as a source of “cognitive load” and can be measured physiologically (Sandi, 2013; Woody et al., 2018). Excess cognitive load due to personal, social, and/or environmental stress affects mood and cognitive function (Berto, 2014; Jiang et al., 2020).

Many studies have repeatedly shown the cognitive benefits of simply viewing greenery, whether real and potentially accessible, or computer-generated and virtual (Jiang et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2014). In fact, it was a study on post-surgery views of trees vs. brick wall from hospital windows (Ulrich, 1984) which catalyzed on-going studies on green mechanisms to health. Evolutionary perspectives posit a “predisposition to pay attention and respond positively to natural content (e.g., vegetation, water) […] that were favorable to survival” induces positive emotions which alleviate physiological stress (Berto, 2014, p. 396).

Studies have explored the therapeutic qualities of greenery in the lives of older adults, including rural settings (Blackstock et al., 2006; Finlay et al., 2015; Williams, 2010). Views of nature reduce heart rates (Lee & Lee, 2014; South et al., 2015), possibly through a fond memory or a sense of being cared/provided for (Blackstock et al., 2006, p. 170), which distracts or resets (instead of restores) one’s attention away from stressful emotions. Such calming symbolic imaginations have been associated with green landscapes through generations (evident in cultural and planning movements; see Machor, 1987; Ruff, 2015).

At the same time, watching plants bloom, grow, and wither through the seasons could help one reappraise one’s life (Wang & MacMillan, 2013). These natural processes closely resemble the life cycle of a person, from infancy, adolescence, adulthood, to late-life. Observing and caring for plants from afar through these rhythms could instill a larger sense of life and resilience to boost confidence and esteem (Nollman, 1996). The meaning and pleasantness of such views may provide reasons to remain engaged with one’s surroundings, and exercise one’s visuospatial skills.

Communal support

Green spaces are sites of social contact (Cattell et al., 2008). Like other neighborhood third places, green spaces are experienced differently by different persons (Clarke et al., 2012; Korpela et al., 2014). Personal and social experiences may modify its cognitive benefits. More cohesive neighborhoods predicted slower cognitive decline among older adults because of increased engagement in social activities and less anxiety (Sharifian et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2020). Social and emotional support summarize these cross-level cognitive processes (Lee & Waite, 2018), especially in communities with better social atmospheres (Gan et al., 2021c; 2021e).

Older adults are diverse (cf. Forsyth et al., 2019). Multimorbidity increases risk of cognitive decline, especially among men (Vassilaki et al., 2015). Coping with multiple illnesses, which is common for two out of three older North Americans (Barnett et al., 2012; Marengoni et al., 2011), can be challenging and lonely (Coventry et al., 2015; Gan et al., 2021d). For those with greater disease burden, going outdoors to interact is “the best distraction strategy for managing symptoms” (Eckerblad et al., 2020, p. 5).

Social connectedness was central to explaining physiological stress reduction found in horticultural therapies for older adults (Ng et al., 2021). This recent finding supports eco-psychological perspectives of human-nature contact, which is proposed to improve emotions and thus relationship with others (Metzner, 1995; Wilson, 1984). Improved emotional support could address loneliness and depression, which comprise 8% of known dementia risks among older adults (Livingston et al., 2020, Fig. 7).

Playful activities

There is now little doubt that green spaces are important for the well-being of people living with dementia (Hernandez, 2007). Based on a review of 19 studies, Mmako and colleagues (2020) identified ways or “mechanisms” that make green spaces beneficial for the mental well-being of people at various stages of dementia, namely social identity, empowerment, and risk-taking (Mmako et al., 2020, pp. 5-7). These may be summarized as “play,” which has been associated with risk-taking (Eberle, 2014). UGS should empower people with dementia to engage in playful risk-taking and regain an identity in a community setting apart from that of a patient (Gan et al., 2021b).

Opportunities to engage in playful activities are important to people living with dementia, and may delay or prevent progression to more severe stages of dementia. They may also provide respite to care partners. Given that people with dementia may feel overly protected and stifled (Mapes, 2017), designs could put care partners at ease while creating space for people with dementia to explore and make decisions. Deducing such studio design briefs from available studies of mechanisms systematically advances dementia-friendly urban design.

Framework

To provide a focus to complex design processes and facilitate research-by-design, we provide a sketch of possible mechanisms that warrant design explorations and testing. We show here one-to-one or many-to-one relationships for simplicity but there may also be one-to-many relationships between green spaces and the intermediate goals identified by Livingston et al. (2020). For example, having green spaces for outdoor activities could reduce exposure to air pollution from vehicles and mitigate its impact.

Figure 1: Possible mechanisms from green spaces to cognition for future research-by-design

We provide here a brief example of a possible application of this framework. A design studio may aim to focus on playful activities as a mechanism that may enhance cognition by reducing loneliness and depression. With reference to the cited literature and other sources, designers might aim to minimise open sides to vehicular traffic, provide lookout points with seating, while incorporating some slopes, shrubs, and planters, water, or play equipment for challenge and interest (cf. Silvia, 2008). The inputs of people with dementia, care partners, and/or other users could be sought before and after iterative ideations with maximum mutuality (Dening et al., 2020; Gan et al., 2021a). Relevant activities may differ greatly based on community inputs.

For scientific advancement, pre- and post-tests are just as important to examine the relevance of the identified mechanisms (South et al., 2015). Relevant and validated scales, including mediators such as loneliness, and/or biomarkers could be used (Ng et al., 2021; Sarabia-Cobo, 2015). Several promising wearable sensor technologies remain under development (Liu & Du, 2018). Measurement issues such as insensitive tests or stark contextual differences should be addressed (ibid.; Zijlema et al., 2017).

For scientific advancement, pre- and post-tests are just as important to examine the relevance of the identified mechanisms (South et al., 2015). Relevant and validated scales, including mediators such as loneliness, and/or biomarkers could be used (Ng et al., 2021; Sarabia-Cobo, 2015). Several promising wearable sensor technologies remain under development (Liu & Du, 2018). Measurement issues such as insensitive tests or stark contextual differences should be addressed (ibid.; Zijlema et al., 2017).

Limitations

It is possible that land-based measures of green spaces had captured the cognitive impact of living in neighborhoods and houses of better quality despite non-exposure to greenery. Despite controlling for individual and neighborhood socioeconomic statuses (e.g., de Keijzer et al., 2018), it is not possible to negate the effects of unmeasured everyday stresses especially amid stark socioeconomic disparities and segregation (Clarke et al., 2012). For example, poor neighborhoods may be subject to police violence and/or air pollution (e.g., PM2.5, NO2) which could affect cognition through post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and pulmonary inflammation/blood-brain barrier respectively (Block & Calderón-Garcidueñas, 2009; Qureshi et al., 2011). Designers should be sensitized to other possibilities, and consider other factors/mechanisms that may negatively impact cognitive health. We indicate these tentatively as “quality housing” in the diagram.

In the event that complex interventions are required, a team of experts on various sources of physiological stress or other technical experts could be consulted. But consulting the community would be most important for sustained improvements. Asset-based community development (ABCD) may be most relevant in the absence of systemic support (Blickem et al., 2018). Given that dementia affects some minority races disproportionately (Mayeda et al., 2016), supporting brain health equity through “equigenic” or place-based interventions is one way that urban designers may contribute to social justice (Loukaitou-Sideris, 2020; Mitchell et al., 2015) so long as they involve equitable labor (Duncan & Duncan, 2003) and mitigate gentrification by prioritizing the concerns of minoritized community members (Bates, 2013; Byers, 2021).

In the event that complex interventions are required, a team of experts on various sources of physiological stress or other technical experts could be consulted. But consulting the community would be most important for sustained improvements. Asset-based community development (ABCD) may be most relevant in the absence of systemic support (Blickem et al., 2018). Given that dementia affects some minority races disproportionately (Mayeda et al., 2016), supporting brain health equity through “equigenic” or place-based interventions is one way that urban designers may contribute to social justice (Loukaitou-Sideris, 2020; Mitchell et al., 2015) so long as they involve equitable labor (Duncan & Duncan, 2003) and mitigate gentrification by prioritizing the concerns of minoritized community members (Bates, 2013; Byers, 2021).

Conclusion

Scholars have been fascinated with the well-being benefits of the environment for centuries (Gifford, 2006). Focusing on “mechanisms” could advance dementia-friendly design practices over time. This article underscored the relevance of mechanisms for research-by-design on greenery, which has the best evidences of cognitive impact. Despite these evidences, theories that could explain its effects remain underdeveloped, which had limited their translation into practice. Design students and researchers could support theoretical development by synthesizing broader literatures and examining them through research-by-design. Studies of other urban design elements could follow a similar approach.

In short, playful activities, pastoral vision, and communal support, are three ways green spaces may prevent cognitive decline. We extended planning-oriented models of cognitive health in ways that are relevant to designers (Cerin, 2019). We invite interested designers and researchers to join the UD/MH Cognitive Interventions Workgroup.

In short, playful activities, pastoral vision, and communal support, are three ways green spaces may prevent cognitive decline. We extended planning-oriented models of cognitive health in ways that are relevant to designers (Cerin, 2019). We invite interested designers and researchers to join the UD/MH Cognitive Interventions Workgroup.

About the Authors

|

Dr. Gan is a community gerontologist at Simon Fraser University, Vancouver. He conducts research at the intersection of planning, psychology and gerontology to improve the cognitive health of older adults living in community. He developed a Transdisciplinary Neighbourhood Health Framework which is the basis of current work on neighbourhood cohesion, loneliness and dementia prevention. @daniel_gry

|

|

Dr. Zhang Liqing is an assistant professor working in the Department of Landscape Architecture, School of Design, Shanghai Jiao Tong University since 2019. She obtained her PhD degree from National University of Singapore in 2019. She has served as the reviewers for The Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF) application and several SCI/SSCI-indexed journals. Her research interests include nature and health, urban ecosystem services, healthy landscape, human and nature interactions.

|

|

Dr. Ng is a translational gerontologist & neuroscientist who specialized in biomarkers and interventions related to aging, mental health & Alzheimer's. Incorporating multiple bio-psycho-social measures, his research program aims to comprehensively examine the modifiable risk factors of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the pre-clinical stage, informing novel non-pharmacological interventions (NPIs) to reduce the risk of developing AD. Key areas: Randomized Controlled Trials; Mindfulness Intervention; Blood & Salivary Biomarkers; Mild Cognitive Impairment; Geriatric Psychiatry; Loneliness & Social Connectedness

@TedKSNg1 |

References

Barnett, K., Mercer, S. W., Norbury, M., Watt, G., Wyke, S., & Guthrie, B. (2012). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet, 380(9836), 37-43.

Bateman, R. J., Xiong, C., Benzinger, T. L., Fagan, A. M., Goate, A., Fox, N. C., ... & Morris, J. C. (2012). Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med, 367, 795-804.

Bates, L. K. (2013). Gentrification and Displacement Study: Implementing an Equitable Inclusive Development Strategy in the Context of Gentrification. Portland: Portland State University Urban Studies and Planning. https://doi.org/10.15760/report-01

Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: a literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral sciences, 4(4), 394-409.

Blickem, C., Dawson, S., Kirk, S., Vassilev, I., Mathieson, A., Harrison, R., ... & Lamb, J. (2018). What is asset-based community development and how might it improve the health of people with long-term conditions? A realist synthesis. Sage Open, 8(3), 2158244018787223.

Block, M. L., & Calderón-Garcidueñas, L. (2009). Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends in neurosciences, 32(9), 506-516.

Byers, M. M. (2021). Houston, We Have a Gentrification Problem: The Gentrification Effects of Local

Environmental Improvement Plans in the City of Houston. Texas A&M Journal of Property Law, 7, 163-198. https://doi.org/10.37419/JPL.V7.I2.2

Celidoni, M., Dal Bianco, C., & Weber, G. (2017). Retirement and cognitive decline. A longitudinal analysis using SHARE data. Journal of health economics, 56, 113-125.

Cerin, E. (2019). Building the evidence for an ecological model of cognitive health. Health & place, 60, 102206.

Clarke, P. J., Ailshire, J. A., House, J. S., Morenoff, J. D., King, K., Melendez, R., & Langa, K. M. (2012). Cognitive function in the community setting: the neighbourhood as a source of ‘cognitive reserve’?. J Epidemiol Community Health, 66(8), 730-736.

Coventry, P. A., Small, N., Panagioti, M., Adeyemi, I., & Bee, P. (2015). Living with complexity; marshalling resources: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis of lived experience of mental and physical multimorbidity. BMC family practice, 16(1), 1-12.

de Keijzer, C., Tonne, C., Basagaña, X., Valentín, A., Singh-Manoux, A., Alonso, J., ... & Dadvand, P. (2018). Residential surrounding greenness and cognitive decline: a 10-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort. Environmental health perspectives, 126(7), 077003.

Dening, T., Gosling, J., Craven, M., & Niedderer, K. (2020). Guidelines for Designing with and for People

with Dementia. MinD. https://designingfordementia.eu/resources/mind-guidelines

Duncan, J., & Duncan, N. (2003). Can’t live with them; can’t landscape without them: racism and the pastoral aesthetic in suburban New York. Landscape Journal, 22(2), 88-98.

Eberle, S. G. (2014). The elements of play: Toward a philosophy and a definition of play. American Journal of Play, 6(2), 214-233.

Eckerblad, J., Waldréus, N., Stark, Å. J., & Jacobsson, L. R. (2020). Symptom management strategies used by older community-dwelling people with multimorbidity and a high symptom burden-a qualitative study. BMC geriatrics, 20(1), 1-9.

Finlay, J., Franke, T., McKay, H., & Sims-Gould, J. (2015). Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: Impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health & place, 34, 97-106.

Forsyth, A., Molinsky, J., & Kan, H. Y. (2019). Improving housing and neighborhoods for the vulnerable: Older people, small households, urban design, and planning. Urban Design International, 24(3), 171-186.

Frumkin, H. (2001). Beyond toxicity: Human health and the natural environment. American journal of preventive medicine, 20, 234-240.

Gan, D. R. Y. (2017). Neighbourhood effects for aging in place: A transdisciplinary framework toward health-promoting settings. Housing and Society, 44(1-2), 79-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2017.1393283

Gan, D. R. Y., Chaudhury, H., Mann, J., & Wister, A. (2021a). Dementia-friendly neighborhood and the built environment: A scoping review. The Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab019

Gan, D. R. Y., Chaudhury, H., & Rowles, G. D. (2021b). Social practices, social identity, and at-homeness while aging in the community: A comparative meta-synthesis of the geographies of home and dementia. Canadian Geographer.

Gan, D. R. Y., Fung, J. C., & Cho, I. S. (2021c). Neighborhood atmosphere modifies the eudaimonic impact of cohesion and friendship among older adults: A multilevel mixed-methods study. Social Science & Medicine, 270, 113682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113682

Gan, D. R. Y., Wister, A., & Best, J. R. (2021d). Environmental Influences of Life Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults with Multimorbidity: CLSA Path Analysis Through Loneliness. The Gerontologist.

Gan, D. R. Y., Cheng, G. H.-L., Ng, T. P., Fung, J. C., & Cho, I. S. (2021e). Neighborhood psychosocial pathways: Exploring the effect of neighborhood cohesion on mental wellbeing. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences.

Gifford, T. (2006). Reconnecting with John Muir: Essays in Post-Pastoral Practice. University of Georgia Press.

Hernandez, R. O. (2007). Effects of therapeutic gardens in special care units for people with dementia: Two case studies. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 21, 117-152.

Jiang, B., He, J., Chen, J., Larsen, L., & Wang, H. (2020). Perceived Green at Speed: A Simulated Driving Experiment Raises New Questions for Attention Restoration Theory and Stress Reduction Theory. Environment and Behavior, 0013916520947111.

Joye, Y., & Dewitte, S. (2018). Nature's broken path to restoration. A critical look at Attention Restoration Theory. Journal of environmental psychology, 59, 1-8.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Korpela, K. M., Ylén, M., Tyrväinen, L., & Silvennoinen, H. (2008). Determinants of restorative experiences in everyday favorite places. Health & place, 14(4), 636-652.

Lee, J. Y., & Lee, D. C. (2014). Cardiac and pulmonary benefits of forest walking versus city walking in elderly women: A randomised, controlled, open-label trial. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 6(1), 5-11.

Lee, H., & Waite, L. J. (2018). Cognition in context: The role of objective and subjective measures of neighborhood and household in cognitive functioning in later life. The Gerontologist, 58(1), 159-169.

Lepore, M., Ferrell, A., & Wiener, J. M. (2017). Living arrangements of people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Implications for services and supports. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Disability, Aging, and Long-Term Care Policy. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/257966/LivingArran.pdf

Lin, Y. H., Tsai, C. C., Sullivan, W. C., Chang, P. J., & Chang, C. Y. (2014). Does awareness effect the restorative function and perception of street trees?. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 906.

Liu, Y., & Du, S. (2018). Psychological stress level detection based on electrodermal activity. Behavioural brain research, 341, 50-53.

Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., ... & Mukadam, N. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 396(10248), 413-446.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2020). Responsibilities and challenges of urban design in the 21st century. Journal of Urban Design, 25(1), 22-24.

Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., Spreeuwenberg, P., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2008). Physical activity as a possible mechanism behind the relationship between green space and health: a multilevel analysis. BMC public health, 8(1), 1-13.

Maas, J., Van Dillen, S. M., Verheij, R. A., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2009). Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health & place, 15(2), 586-595.

Machor, J. L. (1987). Pastoral cities: Urban ideals and the symbolic landscape of America. Univ of Wisconsin Press.

Maller, C., Townsend, M., Pryor, A., Brown, P., & St Leger, L. (2006). Healthy nature healthy people: Contact with nature as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health promotion international, 21, 45-54.

Mapes, N. (2017). Think outside: Positive risk-taking with people living with dementia. Working with Older People, 21, 157–166.

Marengoni, A., Angleman, S., Melis, R., Mangialasche, F., Karp, A., Garmen, A., ... & Fratiglioni, L. (2011). Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing research reviews, 10(4), 430-439.

Mayeda, E. R., Glymour, M. M., Quesenberry, C. P., & Whitmer, R. A. (2016). Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 12(3), 216-224.

Metzner, R. (1995). The psychopathology of the human-nature relationship. Ecopsychology: Restoring the earth, healing the mind, 55-67.

Mitchell, R. J., Richardson, E. A., Shortt, N. K., & Pearce, J. R. (2015). Neighborhood environments and socioeconomic inequalities in mental well-being. American journal of preventive medicine, 49(1), 80-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.017

Mmako, N. J., Courtney-Pratt, H., & Marsh, P. (2020). Green spaces, dementia and a meaningful life in the community: a mixed studies review. Health & Place, 63, 102344.

Ng, T. K. S., Sia, A., Ng, M. K., Tan, C. T., Chan, H. Y., Tan, C. H., ... & Ho, R. C.-M. (2018). Effects of horticultural therapy on Asian older adults: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(8), 1705.

Ng, T. K. S., Gan, D. R. Y., Mahendran, R., Kua, E. H., & Ho, R. C.-M. (2021). Social connectedness as a mediator for horticultural therapy’s biological effect on community-dwelling older adults: Secondary analyses of a randomized controlled trial. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114191

Oi, K. (2017). Inter-connected trends in cognitive aging and depression: Evidence from the health and retirement study. Intelligence, 63, 56-65.

Prince, M., Wimo, A., Guerchet, M., Ali, G. C., Wu, Y. T., & Prina, M. (2015). The global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. World Alzheimer Report, 2015.

Pryor, A., Townsend, M., Maller, C., & Field, K. (2006). Health and well-being naturally: Contact with nature in health promotion for targeted individuals, communities and populations. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 17, 114-123.

Qureshi, S. U., Long, M. E., Bradshaw, M. R., Pyne, J. M., Magruder, K. M., Kimbrell, T., ... & Kunik, M. E. (2011). Does PTSD impair cognition beyond the effect of trauma?. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 23(1), 16-28.

Ruff, A. R. (2015). Arcadian visions: Pastoral influences on poetry, painting and the design of landscape. Windgather Press.

Sandi, C. (2013). Stress and cognition. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 4(3), 245-261.

Sandoval, V. (2018). Green Gentrification Analysis: A Case Study of the East Bay Greenway in Oakland, California. Berkeley: UC Berkeley Environmental Sciences https://nature.berkeley.edu/classes/es196/projects/2018final/SandovalV_2018.pdf

Sarabia-Cobo, C. M. (2015). Heart coherence: a new tool in the management of stress on professionals and family caregivers of patients with dementia. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback, 40(2), 75-83.

Sharifian, N., Spivey, B. N., Zaheed, A. B., & Zahodne, L. B. (2020). Psychological distress links perceived neighborhood characteristics to longitudinal trajectories of cognitive health in older adulthood. Social Science & Medicine, 258, 113125.

Silvia, P. J. (2008). Interest—The curious emotion. Current directions in psychological science, 17(1), 57-60.

South, E. C., Kondo, M. C., Cheney, R. A., & Branas, C. C. (2015). Neighborhood blight, stress, and health: a walking trial of urban greening and ambulatory heart rate. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 909-913.

Tang, F., Zhang, W., Chi, I., Li, M., & Dong, X. Q. (2020). Importance of Activity Engagement and Neighborhood to Cognitive Function Among Older Chinese Americans. Research on aging, 42(7-8), 226-235.

Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224,

420–421.

Vassilaki, M., Aakre, J. A., Cha, R. H., Kremers, W. K., St. Sauver, J. L., Mielke, M. M., ... & Roberts, R. O. (2015). Multimorbidity and risk of mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(9), 1783-1790.

Wang, D., & MacMillan, T. (2013). The benefits of gardening for older adults: a systematic review of the literature. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 37(2), 153-181.

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wong, G. C. L., Ng, T. K. S., Lee, J. L., Lim, P. Y., Chua, S. K. J., Tan, C., ... & Larbi, A. (2021). Horticultural Therapy Reduces Biomarkers of Immunosenescence and Inflammaging in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Feasibility Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 76(2), 307-317.

Woody, A., Hooker, E. D., Zoccola, P. M., & Dickerson, S. S. (2018). Social-evaluative threat, cognitive load, and the cortisol and cardiovascular stress response. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 97, 149-155.

Zijlema, W. L., Triguero-Mas, M., Smith, G., Cirach, M., Martinez, D., Dadvand, P., ... & Julvez, J. (2017). The relationship between natural outdoor environments and cognitive functioning and its mediators. Environmental research, 155, 268-275.

Bateman, R. J., Xiong, C., Benzinger, T. L., Fagan, A. M., Goate, A., Fox, N. C., ... & Morris, J. C. (2012). Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med, 367, 795-804.

Bates, L. K. (2013). Gentrification and Displacement Study: Implementing an Equitable Inclusive Development Strategy in the Context of Gentrification. Portland: Portland State University Urban Studies and Planning. https://doi.org/10.15760/report-01

Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: a literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral sciences, 4(4), 394-409.

Blickem, C., Dawson, S., Kirk, S., Vassilev, I., Mathieson, A., Harrison, R., ... & Lamb, J. (2018). What is asset-based community development and how might it improve the health of people with long-term conditions? A realist synthesis. Sage Open, 8(3), 2158244018787223.

Block, M. L., & Calderón-Garcidueñas, L. (2009). Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends in neurosciences, 32(9), 506-516.

Byers, M. M. (2021). Houston, We Have a Gentrification Problem: The Gentrification Effects of Local

Environmental Improvement Plans in the City of Houston. Texas A&M Journal of Property Law, 7, 163-198. https://doi.org/10.37419/JPL.V7.I2.2

Celidoni, M., Dal Bianco, C., & Weber, G. (2017). Retirement and cognitive decline. A longitudinal analysis using SHARE data. Journal of health economics, 56, 113-125.

Cerin, E. (2019). Building the evidence for an ecological model of cognitive health. Health & place, 60, 102206.

Clarke, P. J., Ailshire, J. A., House, J. S., Morenoff, J. D., King, K., Melendez, R., & Langa, K. M. (2012). Cognitive function in the community setting: the neighbourhood as a source of ‘cognitive reserve’?. J Epidemiol Community Health, 66(8), 730-736.

Coventry, P. A., Small, N., Panagioti, M., Adeyemi, I., & Bee, P. (2015). Living with complexity; marshalling resources: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis of lived experience of mental and physical multimorbidity. BMC family practice, 16(1), 1-12.

de Keijzer, C., Tonne, C., Basagaña, X., Valentín, A., Singh-Manoux, A., Alonso, J., ... & Dadvand, P. (2018). Residential surrounding greenness and cognitive decline: a 10-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort. Environmental health perspectives, 126(7), 077003.

Dening, T., Gosling, J., Craven, M., & Niedderer, K. (2020). Guidelines for Designing with and for People

with Dementia. MinD. https://designingfordementia.eu/resources/mind-guidelines

Duncan, J., & Duncan, N. (2003). Can’t live with them; can’t landscape without them: racism and the pastoral aesthetic in suburban New York. Landscape Journal, 22(2), 88-98.

Eberle, S. G. (2014). The elements of play: Toward a philosophy and a definition of play. American Journal of Play, 6(2), 214-233.

Eckerblad, J., Waldréus, N., Stark, Å. J., & Jacobsson, L. R. (2020). Symptom management strategies used by older community-dwelling people with multimorbidity and a high symptom burden-a qualitative study. BMC geriatrics, 20(1), 1-9.

Finlay, J., Franke, T., McKay, H., & Sims-Gould, J. (2015). Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: Impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health & place, 34, 97-106.

Forsyth, A., Molinsky, J., & Kan, H. Y. (2019). Improving housing and neighborhoods for the vulnerable: Older people, small households, urban design, and planning. Urban Design International, 24(3), 171-186.

Frumkin, H. (2001). Beyond toxicity: Human health and the natural environment. American journal of preventive medicine, 20, 234-240.

Gan, D. R. Y. (2017). Neighbourhood effects for aging in place: A transdisciplinary framework toward health-promoting settings. Housing and Society, 44(1-2), 79-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2017.1393283

Gan, D. R. Y., Chaudhury, H., Mann, J., & Wister, A. (2021a). Dementia-friendly neighborhood and the built environment: A scoping review. The Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab019

Gan, D. R. Y., Chaudhury, H., & Rowles, G. D. (2021b). Social practices, social identity, and at-homeness while aging in the community: A comparative meta-synthesis of the geographies of home and dementia. Canadian Geographer.

Gan, D. R. Y., Fung, J. C., & Cho, I. S. (2021c). Neighborhood atmosphere modifies the eudaimonic impact of cohesion and friendship among older adults: A multilevel mixed-methods study. Social Science & Medicine, 270, 113682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113682

Gan, D. R. Y., Wister, A., & Best, J. R. (2021d). Environmental Influences of Life Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults with Multimorbidity: CLSA Path Analysis Through Loneliness. The Gerontologist.

Gan, D. R. Y., Cheng, G. H.-L., Ng, T. P., Fung, J. C., & Cho, I. S. (2021e). Neighborhood psychosocial pathways: Exploring the effect of neighborhood cohesion on mental wellbeing. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences.

Gifford, T. (2006). Reconnecting with John Muir: Essays in Post-Pastoral Practice. University of Georgia Press.

Hernandez, R. O. (2007). Effects of therapeutic gardens in special care units for people with dementia: Two case studies. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 21, 117-152.

Jiang, B., He, J., Chen, J., Larsen, L., & Wang, H. (2020). Perceived Green at Speed: A Simulated Driving Experiment Raises New Questions for Attention Restoration Theory and Stress Reduction Theory. Environment and Behavior, 0013916520947111.

Joye, Y., & Dewitte, S. (2018). Nature's broken path to restoration. A critical look at Attention Restoration Theory. Journal of environmental psychology, 59, 1-8.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Korpela, K. M., Ylén, M., Tyrväinen, L., & Silvennoinen, H. (2008). Determinants of restorative experiences in everyday favorite places. Health & place, 14(4), 636-652.

Lee, J. Y., & Lee, D. C. (2014). Cardiac and pulmonary benefits of forest walking versus city walking in elderly women: A randomised, controlled, open-label trial. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 6(1), 5-11.

Lee, H., & Waite, L. J. (2018). Cognition in context: The role of objective and subjective measures of neighborhood and household in cognitive functioning in later life. The Gerontologist, 58(1), 159-169.

Lepore, M., Ferrell, A., & Wiener, J. M. (2017). Living arrangements of people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Implications for services and supports. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Disability, Aging, and Long-Term Care Policy. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/257966/LivingArran.pdf

Lin, Y. H., Tsai, C. C., Sullivan, W. C., Chang, P. J., & Chang, C. Y. (2014). Does awareness effect the restorative function and perception of street trees?. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 906.

Liu, Y., & Du, S. (2018). Psychological stress level detection based on electrodermal activity. Behavioural brain research, 341, 50-53.

Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., ... & Mukadam, N. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 396(10248), 413-446.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2020). Responsibilities and challenges of urban design in the 21st century. Journal of Urban Design, 25(1), 22-24.

Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., Spreeuwenberg, P., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2008). Physical activity as a possible mechanism behind the relationship between green space and health: a multilevel analysis. BMC public health, 8(1), 1-13.

Maas, J., Van Dillen, S. M., Verheij, R. A., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2009). Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health & place, 15(2), 586-595.

Machor, J. L. (1987). Pastoral cities: Urban ideals and the symbolic landscape of America. Univ of Wisconsin Press.

Maller, C., Townsend, M., Pryor, A., Brown, P., & St Leger, L. (2006). Healthy nature healthy people: Contact with nature as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health promotion international, 21, 45-54.

Mapes, N. (2017). Think outside: Positive risk-taking with people living with dementia. Working with Older People, 21, 157–166.

Marengoni, A., Angleman, S., Melis, R., Mangialasche, F., Karp, A., Garmen, A., ... & Fratiglioni, L. (2011). Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing research reviews, 10(4), 430-439.

Mayeda, E. R., Glymour, M. M., Quesenberry, C. P., & Whitmer, R. A. (2016). Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 12(3), 216-224.

Metzner, R. (1995). The psychopathology of the human-nature relationship. Ecopsychology: Restoring the earth, healing the mind, 55-67.

Mitchell, R. J., Richardson, E. A., Shortt, N. K., & Pearce, J. R. (2015). Neighborhood environments and socioeconomic inequalities in mental well-being. American journal of preventive medicine, 49(1), 80-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.017

Mmako, N. J., Courtney-Pratt, H., & Marsh, P. (2020). Green spaces, dementia and a meaningful life in the community: a mixed studies review. Health & Place, 63, 102344.

Ng, T. K. S., Sia, A., Ng, M. K., Tan, C. T., Chan, H. Y., Tan, C. H., ... & Ho, R. C.-M. (2018). Effects of horticultural therapy on Asian older adults: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(8), 1705.

Ng, T. K. S., Gan, D. R. Y., Mahendran, R., Kua, E. H., & Ho, R. C.-M. (2021). Social connectedness as a mediator for horticultural therapy’s biological effect on community-dwelling older adults: Secondary analyses of a randomized controlled trial. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114191

Oi, K. (2017). Inter-connected trends in cognitive aging and depression: Evidence from the health and retirement study. Intelligence, 63, 56-65.

Prince, M., Wimo, A., Guerchet, M., Ali, G. C., Wu, Y. T., & Prina, M. (2015). The global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. World Alzheimer Report, 2015.

Pryor, A., Townsend, M., Maller, C., & Field, K. (2006). Health and well-being naturally: Contact with nature in health promotion for targeted individuals, communities and populations. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 17, 114-123.

Qureshi, S. U., Long, M. E., Bradshaw, M. R., Pyne, J. M., Magruder, K. M., Kimbrell, T., ... & Kunik, M. E. (2011). Does PTSD impair cognition beyond the effect of trauma?. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 23(1), 16-28.

Ruff, A. R. (2015). Arcadian visions: Pastoral influences on poetry, painting and the design of landscape. Windgather Press.

Sandi, C. (2013). Stress and cognition. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 4(3), 245-261.

Sandoval, V. (2018). Green Gentrification Analysis: A Case Study of the East Bay Greenway in Oakland, California. Berkeley: UC Berkeley Environmental Sciences https://nature.berkeley.edu/classes/es196/projects/2018final/SandovalV_2018.pdf

Sarabia-Cobo, C. M. (2015). Heart coherence: a new tool in the management of stress on professionals and family caregivers of patients with dementia. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback, 40(2), 75-83.

Sharifian, N., Spivey, B. N., Zaheed, A. B., & Zahodne, L. B. (2020). Psychological distress links perceived neighborhood characteristics to longitudinal trajectories of cognitive health in older adulthood. Social Science & Medicine, 258, 113125.

Silvia, P. J. (2008). Interest—The curious emotion. Current directions in psychological science, 17(1), 57-60.

South, E. C., Kondo, M. C., Cheney, R. A., & Branas, C. C. (2015). Neighborhood blight, stress, and health: a walking trial of urban greening and ambulatory heart rate. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 909-913.

Tang, F., Zhang, W., Chi, I., Li, M., & Dong, X. Q. (2020). Importance of Activity Engagement and Neighborhood to Cognitive Function Among Older Chinese Americans. Research on aging, 42(7-8), 226-235.

Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224,

420–421.

Vassilaki, M., Aakre, J. A., Cha, R. H., Kremers, W. K., St. Sauver, J. L., Mielke, M. M., ... & Roberts, R. O. (2015). Multimorbidity and risk of mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(9), 1783-1790.

Wang, D., & MacMillan, T. (2013). The benefits of gardening for older adults: a systematic review of the literature. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 37(2), 153-181.

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wong, G. C. L., Ng, T. K. S., Lee, J. L., Lim, P. Y., Chua, S. K. J., Tan, C., ... & Larbi, A. (2021). Horticultural Therapy Reduces Biomarkers of Immunosenescence and Inflammaging in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Feasibility Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 76(2), 307-317.

Woody, A., Hooker, E. D., Zoccola, P. M., & Dickerson, S. S. (2018). Social-evaluative threat, cognitive load, and the cortisol and cardiovascular stress response. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 97, 149-155.

Zijlema, W. L., Triguero-Mas, M., Smith, G., Cirach, M., Martinez, D., Dadvand, P., ... & Julvez, J. (2017). The relationship between natural outdoor environments and cognitive functioning and its mediators. Environmental research, 155, 268-275.