Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2021:7;9

CASE STUDY

Towards an Alternative Design Culture to Empower Older People through Active Ageing

Sharyl Ng Yun Hui and Ye Zhang

National University of Singapore

National University of Singapore

Hui SNY, Zhang Y (2021). Towards an alternative design culture to empower older people through active ageing. Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 7;9

Abstract

Ageing is commonly considered a serious social issue with a constantly increasing ageing population alongside lower birth rates worldwide. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), older people can sometimes be considered 'useless' and 'incapable' and can be regarded as consumers of resources instead of as contributors. This creates age-divided societies where many older people feel marginalized from society and misunderstood simply because of their age, affecting their mental and physical well-being. Unlike racism, ageism is usually ignored or overlooked especially in today's capitalist economy, where the value of citizens and objects are often based on their economic contribution and skillsets. However, older people are essential to adding social and cultural value to the state and society.

This paper seeks to suggest an alternate design culture that could possibly empower older people through public participation for active ageing. The theme is developed by first discussing misconceptions in ageism attitudes, and how they led to the creation of retirement communities with the good intent of improving older people’s physical and mental well-being, but resulted in undesirable consequence of worsening their well-being by isolating them from society. Upon reflection on the retirement community, the notion of active ageing is then introduced to encourage older people to contribute to society through social or economic means where their communities should help to facilitate these contributions. Lastly, an alternative design for social innovation is introduced to potential include new solutions that could further improve the well-being of older people by involving them in discussions and implementation phases to solve issues that they faced in their community.

This paper seeks to suggest an alternate design culture that could possibly empower older people through public participation for active ageing. The theme is developed by first discussing misconceptions in ageism attitudes, and how they led to the creation of retirement communities with the good intent of improving older people’s physical and mental well-being, but resulted in undesirable consequence of worsening their well-being by isolating them from society. Upon reflection on the retirement community, the notion of active ageing is then introduced to encourage older people to contribute to society through social or economic means where their communities should help to facilitate these contributions. Lastly, an alternative design for social innovation is introduced to potential include new solutions that could further improve the well-being of older people by involving them in discussions and implementation phases to solve issues that they faced in their community.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defined ageism as a stereotype, or as a form of discrimination against people based on their age. Unlike racism, age-based prejudice may be the most socially 'normalised' type of prejudice; it has been ingrained in society in many places, and affects the quality of life of older adults. This is also an issue because many older adults have become accustomed to this discrimination.

With regards to today's capitalist and evolving technological-driven society, ageism is often expressed as older working individuals taking mandatory retirement. In a society where the entire media and publishing industry glorifies youth and the constant portraying of ageing almost exclusively in forms of loss of physical and mental abilities such as using older people as models to advertise medical supplements to strengthen bones. Through this popular imagery, it led us to fear to age. Labeling older people as 'the other' has been a way to distance ourselves from that anxiety due to the misconception that getting older is all loss and no gain (Schloredt, 2019).

There are three main misconceptions associated with older people. The first is the generalization that all older adults behave in the same way, or have the same needs or experiences (WHO, 2015). Age and physical decline are not always linearly related. Older age is characterised by diversity where some may require different levels of care or support; some are independent and others are as healthy and functional as many younger people.

Secondly, some people have tended to regard older people as useless, less intelligent, stingy, and a burden or a drain on public resources (WHO, 2015). However, this is not true. Older adults are needed to support young and older people in many ways. Whether they are working or retired, they still contribute to the economy by buying products and serves, contribute labor, support, and finances to their families when they require help.

Lastly, there is a misconception that older people are 'overpaid and unproductive' (Greedy, 2020). The retrenchment of older adults does not necessarily create job opportunities for the youth but instead reduces the older worker's ability to contribute to the economy. The experience and skillset in which older adults are equipped will be gone into waste as companies are not able to capitalize on them.

Due to these misconceptions, older people can be regarded as ‘invisible’ in society, which can be cause and effect of social isolation, one of the main contributors to the decline in people's health, increasing a person’s risk of premature death, depression, and dementia (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Many older people have relocated to senior-friendly communities and nursing homes in hopes of improving their physical and mental well-being, while lessening the 'burden' on their families.

With regards to today's capitalist and evolving technological-driven society, ageism is often expressed as older working individuals taking mandatory retirement. In a society where the entire media and publishing industry glorifies youth and the constant portraying of ageing almost exclusively in forms of loss of physical and mental abilities such as using older people as models to advertise medical supplements to strengthen bones. Through this popular imagery, it led us to fear to age. Labeling older people as 'the other' has been a way to distance ourselves from that anxiety due to the misconception that getting older is all loss and no gain (Schloredt, 2019).

There are three main misconceptions associated with older people. The first is the generalization that all older adults behave in the same way, or have the same needs or experiences (WHO, 2015). Age and physical decline are not always linearly related. Older age is characterised by diversity where some may require different levels of care or support; some are independent and others are as healthy and functional as many younger people.

Secondly, some people have tended to regard older people as useless, less intelligent, stingy, and a burden or a drain on public resources (WHO, 2015). However, this is not true. Older adults are needed to support young and older people in many ways. Whether they are working or retired, they still contribute to the economy by buying products and serves, contribute labor, support, and finances to their families when they require help.

Lastly, there is a misconception that older people are 'overpaid and unproductive' (Greedy, 2020). The retrenchment of older adults does not necessarily create job opportunities for the youth but instead reduces the older worker's ability to contribute to the economy. The experience and skillset in which older adults are equipped will be gone into waste as companies are not able to capitalize on them.

Due to these misconceptions, older people can be regarded as ‘invisible’ in society, which can be cause and effect of social isolation, one of the main contributors to the decline in people's health, increasing a person’s risk of premature death, depression, and dementia (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Many older people have relocated to senior-friendly communities and nursing homes in hopes of improving their physical and mental well-being, while lessening the 'burden' on their families.

Retirement communities

The later phase of life is often marketed as a 'lifestyle' in many countries that promise retirement communities where there are endless activities for older people to enjoy while having their basic needs for safety and health met. Many real estate urban developers have started providing facilities that cater to the needs of groups of older people. Along with the conventional idea of ageing in place, the intention is that retirement communities can help older people to live in the community independently (Buffel et al., 2012).

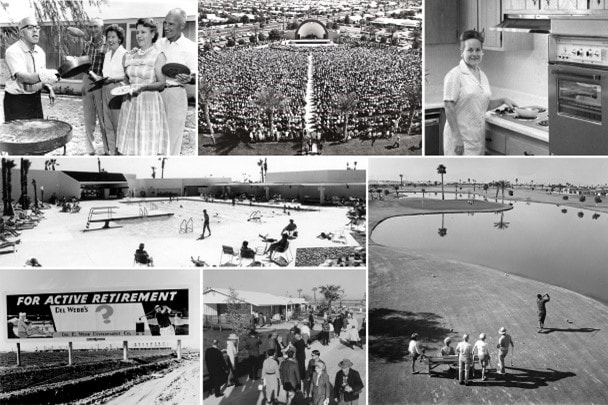

Sun City Arizona is considered as the largest age-segregated active retirement community in the United States of America. It was developed and marketed with the intent to create a new way of life for older people who are “too old to work and too young to die” (Simpson, 2015). Sun City Arizona was conceived based on market research done by experts where a conceptual framework of “activity theory” was tested (Simpson, 2015). This concept created an oasis for the retired, active adult to keep themselves occupied daily while providing an affordable, low-tax lifestyle (Figure 1). Besides providing a series of entertainment and recreational activities, Sun City offers a series of senior housing and continuing care options such as assisted living within the community which is catered to the resident’s needs. The locations of these facilities are planned according to their proximity to recreation, restaurants, and healthcare (Figure 2). Getting around is easy as all homes are located within the community and residents use their own licensed golf carts for mobility. Furthermore, Sun City is well known for its healthcare facilities and its focus on individuals as a community.

Sun City Arizona is considered as the largest age-segregated active retirement community in the United States of America. It was developed and marketed with the intent to create a new way of life for older people who are “too old to work and too young to die” (Simpson, 2015). Sun City Arizona was conceived based on market research done by experts where a conceptual framework of “activity theory” was tested (Simpson, 2015). This concept created an oasis for the retired, active adult to keep themselves occupied daily while providing an affordable, low-tax lifestyle (Figure 1). Besides providing a series of entertainment and recreational activities, Sun City offers a series of senior housing and continuing care options such as assisted living within the community which is catered to the resident’s needs. The locations of these facilities are planned according to their proximity to recreation, restaurants, and healthcare (Figure 2). Getting around is easy as all homes are located within the community and residents use their own licensed golf carts for mobility. Furthermore, Sun City is well known for its healthcare facilities and its focus on individuals as a community.

Figure 1: Sun City opened in 1960. Source: Sun City Arizona, https://suncityaz.org/discover/history/

Figure 2 - Sun City today, showing shared facilities in the nucleus of the development. Source: Sun City Arizona, https://suncityaz.org/

The transition to retirement has the potential to trigger a loss of identity and self-confidence which can affect older people's sense of purpose and can lead to depression (Osborne, 2012). Although retirement communities like Sun City Arizona promise to improve older people's quality of life physically and socially, the creation of such communities also runs the risk of further segregating older people from society based on age, income, or race (Simpson, 2015). Contrary to the positive intentions of retirement communities, this type of segregation runs the risk of negatively affecting older people’s mental wellbeing by limiting their social circle to a very limited demographic group. Additionally, constant exposure to a dwindling social circle due to factors like death, relocation, and decreased mobility may cause one to feel more isolated which can trigger loneliness and depression (Singh & Misra, 2009).

According to Simpson (2015), the concept of ageing in place for retirement communities is compelling in terms of place attachment and the need for a familiar setting. However, the concept of place is much more complex. The key factor in successful examples of ageing in place is the term ‘naturally occurring retirement communities’ (NORCs) (Buffel, 2018). These neighborhoods were naturally evolved into communities of older adults after the younger people migrated away and they enable older people to age together with their society.

Older people can be more sensitive to changes to their physical environment, and some rely on their surroundings for their sense of identity and mobility (Buffel et al., 2012). Hence, it is not ideal for older people to be removed from the society that they are familiar with to be relocated to a retirement community. We as human beings rely on our connection with others and our environment to survive and thrive (National Institute of Aging, 2019). From an economic standpoint, the creation of specialised services to serve an older community specifically would not be a viable and sustainable model. Much of these services could benefit a community made up of different demographics if the growth of a person over a lifetime (ageing in place) is taken into consideration instead of promoting an aspect particular to old age. Perhaps we should look beyond the recuperation of older communities to how to facilitate their self-reliance and engagement within wider society.

According to Simpson (2015), the concept of ageing in place for retirement communities is compelling in terms of place attachment and the need for a familiar setting. However, the concept of place is much more complex. The key factor in successful examples of ageing in place is the term ‘naturally occurring retirement communities’ (NORCs) (Buffel, 2018). These neighborhoods were naturally evolved into communities of older adults after the younger people migrated away and they enable older people to age together with their society.

Older people can be more sensitive to changes to their physical environment, and some rely on their surroundings for their sense of identity and mobility (Buffel et al., 2012). Hence, it is not ideal for older people to be removed from the society that they are familiar with to be relocated to a retirement community. We as human beings rely on our connection with others and our environment to survive and thrive (National Institute of Aging, 2019). From an economic standpoint, the creation of specialised services to serve an older community specifically would not be a viable and sustainable model. Much of these services could benefit a community made up of different demographics if the growth of a person over a lifetime (ageing in place) is taken into consideration instead of promoting an aspect particular to old age. Perhaps we should look beyond the recuperation of older communities to how to facilitate their self-reliance and engagement within wider society.

Active Ageing in Place

Many countries support the theme of active ageing to facilitate the livelihood of older people in their societies. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2002), being ‘active’ does not refer to the absence of diseases but to the holistic approach that encourages a person to continue to participate in social, cultural, spiritual, economic, and civic matters while optimising and maintaining their physical, mental, and social health over the course of their lives. It portrays the importance of moving past ideas of dependency and institutionalisation, and that designing for an ageing population goes beyond designing car-free zones and care services. In 2006, the WHO launched the ‘Global Age-friendly Cities’ project addressing points of service provision, the built environment, and social aspects to make cities friendly for all ages (Buffel, 2018). Active ageing helps to promote healthy living which would extend life expectancy and quality of life despite being frail or disabled thus empowering older people to effectively break away from social isolation.

Active ageing as a concept works well as a system that empowers older people by focusing on achieving healthy and positive ways of ageing (Fernandez et al., 2013). However, to push this idea further, infrastructure is needed to facilitate the reorganization of these social and physical systems and it can be achieved through different scales and ways such as mobility. Therefore, the built environment plays an important role in ageing in a positive light. To discuss and elaborate the term ‘active ageing’ further, the remainder of this article will explore different approaches such as active ageing through continuation of work, mobility and co-design.

Active Ageing through Continuation to Work

Active ageing’s main goals are to ensure that the older community maintains their mobility, physical and mental health by having them constantly be engaged with natural, current activities. Active ageing through continuation to work helps older community to be more well versed and to date with the current industry, helping them to participate in the social and economic nuances of society.

The first example is Gingko House which was founded by a group of older home volunteers after witnessing many older adults facing depression when facing difficulties in seeking re-employment. It is a bottom-up approach that emphasises the participation of older people in society in terms of employment and fosters relationships with other age groups (WHO, 2007). It is the first catering service and restaurant enterprise located in Hong Kong where only older adults are employed. As of 2017, two thousand older adults have been employed by Gingko House (Varsity, 2017).

Besides generating welfare for older people by engaging in business while also providing job opportunities to those with financial or psychological needs (Lee, 2019) the main social objective is to engage with older people who are feeling dejected, lost or otherwise struggling to adjust to retirement life (Li, 2016). Gingko House restaurant is run by older adults within the organisation's social service centre. It provides a suitable working environment and employment opportunity for older adults who wish to work and stay active. One of the employees, Siu mentioned that the employment at Gingko House "changed her life" (Varsity, 2017). She was feeling depressed when she was let go from her previous company and faced multiple challenges in getting re-employed. The job opportunity at Gingko House gave her confidence and happiness as she felt that getting hired in her sixties was an accomplishment. Prior to this, she felt she was deemed useless as no one was willing to hire her, preventing her from contributing to society. Among all her duties, she enjoys interacting, exchanging knowledge and skills with the customers of different ages (Figure 3). Gingko House is more than a successful business as it also sets an example in society for more organisations to be more willing to employ older people.

Before employment, older adults must undergo a series of training workshops to ensure their quality of service (Figure 4). This will benefit the older adults as exercising one’s mental capacity can improve cognitive function. As the brain shrinks with age, learning and challenging the brain can build new neural connections which are traits that are linked to healthy ageing (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2020). Comparing to retirement communities (Sun City Arizona), instead of living in excess pleasure, active ageing through employment gives older people a sense of purpose and usefulness to the community that they are serving.

Active ageing as a concept works well as a system that empowers older people by focusing on achieving healthy and positive ways of ageing (Fernandez et al., 2013). However, to push this idea further, infrastructure is needed to facilitate the reorganization of these social and physical systems and it can be achieved through different scales and ways such as mobility. Therefore, the built environment plays an important role in ageing in a positive light. To discuss and elaborate the term ‘active ageing’ further, the remainder of this article will explore different approaches such as active ageing through continuation of work, mobility and co-design.

Active Ageing through Continuation to Work

Active ageing’s main goals are to ensure that the older community maintains their mobility, physical and mental health by having them constantly be engaged with natural, current activities. Active ageing through continuation to work helps older community to be more well versed and to date with the current industry, helping them to participate in the social and economic nuances of society.

The first example is Gingko House which was founded by a group of older home volunteers after witnessing many older adults facing depression when facing difficulties in seeking re-employment. It is a bottom-up approach that emphasises the participation of older people in society in terms of employment and fosters relationships with other age groups (WHO, 2007). It is the first catering service and restaurant enterprise located in Hong Kong where only older adults are employed. As of 2017, two thousand older adults have been employed by Gingko House (Varsity, 2017).

Besides generating welfare for older people by engaging in business while also providing job opportunities to those with financial or psychological needs (Lee, 2019) the main social objective is to engage with older people who are feeling dejected, lost or otherwise struggling to adjust to retirement life (Li, 2016). Gingko House restaurant is run by older adults within the organisation's social service centre. It provides a suitable working environment and employment opportunity for older adults who wish to work and stay active. One of the employees, Siu mentioned that the employment at Gingko House "changed her life" (Varsity, 2017). She was feeling depressed when she was let go from her previous company and faced multiple challenges in getting re-employed. The job opportunity at Gingko House gave her confidence and happiness as she felt that getting hired in her sixties was an accomplishment. Prior to this, she felt she was deemed useless as no one was willing to hire her, preventing her from contributing to society. Among all her duties, she enjoys interacting, exchanging knowledge and skills with the customers of different ages (Figure 3). Gingko House is more than a successful business as it also sets an example in society for more organisations to be more willing to employ older people.

Before employment, older adults must undergo a series of training workshops to ensure their quality of service (Figure 4). This will benefit the older adults as exercising one’s mental capacity can improve cognitive function. As the brain shrinks with age, learning and challenging the brain can build new neural connections which are traits that are linked to healthy ageing (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2020). Comparing to retirement communities (Sun City Arizona), instead of living in excess pleasure, active ageing through employment gives older people a sense of purpose and usefulness to the community that they are serving.

Figure 3 - An employee serving a group of youth at Gingko House. Source: BBC News 2016.

Figure 4 - Gingko House employees undergoing a training workshop. Source: PowerSupport.

Active Ageing through Mobility

Active ageing through mobility helps to prepare and condition older people physically to be able to navigate around the city independently. Through this, it gives older people a sense of confidence in themselves. The Dream of Mizuumi Centre in Tokyo is an example which is purposefully designed to be low-tech to encourage older adults to be physically active. It had gained international attention from the United Nations and was included in their database of projects for sustainable, ageing societies (Tai, Seow, 2016). Unlike most day-care centres where older adults follow a structured timetable as passive recipients of care, the centre focuses on empowering them to be self-reliant. They must choose what they want to do and eat for the day and make their way to each activity by themselves (Figure 5).

The centre also has an earn-and-spend policy to motivate the older adults to take part in rehab and cognitive training activities. They can "earn money" once they complete their rehab and exchange them for massages, snacks or learning a new skill. Although some of the older people use wheelchairs and walking aids, the centre is “deliberately not barrier-free”, as opposed to many retirement communities that have designed an obstacle free environment that enables older people to move around safely and easily. The centre aims instead to mimic the streets in Tokyo - including their obstacles (Genki Kaki, 2020). Instead of railings or grab bars, there are ropes for the support that aims to strengthen users' upper and lower body coordination (Figure 6). Mobility in the centre is a form of rehabilitation and exercise itself. The design of the centre is intended to benefit its users as they oversee their own programs and safety, thus empowering them with the ability to choose and having a sense of purpose and achievement.

Active ageing through mobility helps to prepare and condition older people physically to be able to navigate around the city independently. Through this, it gives older people a sense of confidence in themselves. The Dream of Mizuumi Centre in Tokyo is an example which is purposefully designed to be low-tech to encourage older adults to be physically active. It had gained international attention from the United Nations and was included in their database of projects for sustainable, ageing societies (Tai, Seow, 2016). Unlike most day-care centres where older adults follow a structured timetable as passive recipients of care, the centre focuses on empowering them to be self-reliant. They must choose what they want to do and eat for the day and make their way to each activity by themselves (Figure 5).

The centre also has an earn-and-spend policy to motivate the older adults to take part in rehab and cognitive training activities. They can "earn money" once they complete their rehab and exchange them for massages, snacks or learning a new skill. Although some of the older people use wheelchairs and walking aids, the centre is “deliberately not barrier-free”, as opposed to many retirement communities that have designed an obstacle free environment that enables older people to move around safely and easily. The centre aims instead to mimic the streets in Tokyo - including their obstacles (Genki Kaki, 2020). Instead of railings or grab bars, there are ropes for the support that aims to strengthen users' upper and lower body coordination (Figure 6). Mobility in the centre is a form of rehabilitation and exercise itself. The design of the centre is intended to benefit its users as they oversee their own programs and safety, thus empowering them with the ability to choose and having a sense of purpose and achievement.

Figure 5 - Dream of Mizumi Centre, Tokyo. Older people can be seen queuing for food and pushing their carts back to their tables. Source: The Straits Times.

Figure 6: An older adult uses ropes to climb the stairs as a form of rehabilitation after a leg injury. Source: Straits Times.

However, mainstream design can be considered to exclude certain people or demographics by applying a normalization or generalised approach. According to Scharf’s (2002) study on 600 older people living in inner-city communities in Liverpool, London and Manchester, older people can feel ‘excluded’ from organisations and institutions which influences the quality of life in their neighborhoods (Buffel, 2018). With these issues in mind, more designers are adapting their design ideation process to be more inclusive and designing for the opportunity for social integration and innovation by placing older people at the center of the focus (Cozza, 2019 & Remillard et al., 2017).

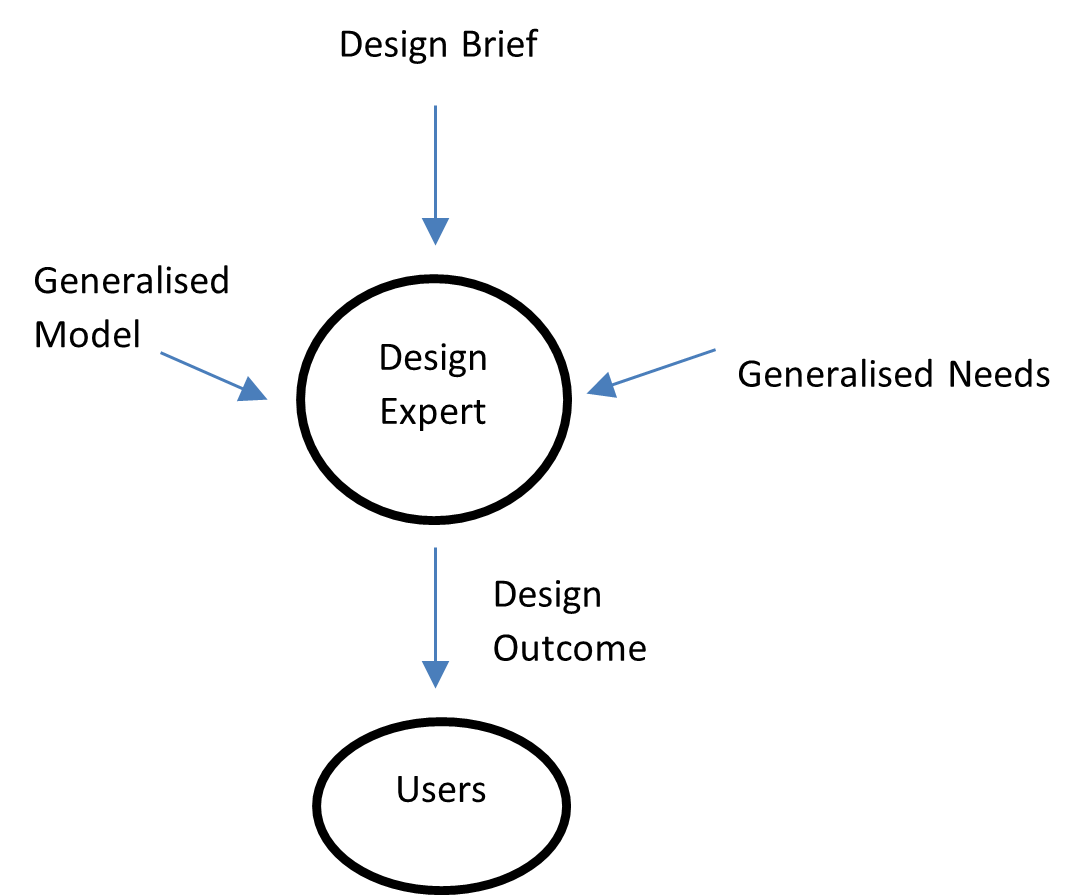

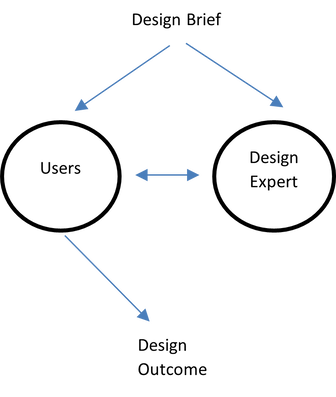

Manzini introduced the concept of 'design for social innovation' (2015) where he combines social innovation with design and distinguishes between design that is performed by everyone and expert design that is performed by designers. Social innovation is distinguishable as it involves collaboration and co-production between stakeholders and the public. The move from user-centric design to co-design implies a change of role played by design experts and users in the ideation process (Figure 7 & 8). In a generalised user-centric design process, the user is a passive object of study, and the design experts receive collated knowledge from their sources and apply their creative thinking skills into the ideas. Whereas for co-design, there are no dedicated roles, instead of only benefiting from the new initiatives, older people will be trained to play an active role in discussions. Involving older people is crucial as it is moving away from generalized views to first-hand experiences to identify existing or new issues to be adjusted or implemented (Remillard et al., 2017). The approach also has the potential to challenge ageism attitudes, promote empowerment among older people in the context of social isolation (Ray, 2007 as cited in Buffel, 2018). This will help to promote civic and social participation among the older people in the neighborhood and improve their physical well-being by keeping them active, stimulating their mind and senses while having a space free from other responsibilities (Remillard et al., 2017).

Manzini introduced the concept of 'design for social innovation' (2015) where he combines social innovation with design and distinguishes between design that is performed by everyone and expert design that is performed by designers. Social innovation is distinguishable as it involves collaboration and co-production between stakeholders and the public. The move from user-centric design to co-design implies a change of role played by design experts and users in the ideation process (Figure 7 & 8). In a generalised user-centric design process, the user is a passive object of study, and the design experts receive collated knowledge from their sources and apply their creative thinking skills into the ideas. Whereas for co-design, there are no dedicated roles, instead of only benefiting from the new initiatives, older people will be trained to play an active role in discussions. Involving older people is crucial as it is moving away from generalized views to first-hand experiences to identify existing or new issues to be adjusted or implemented (Remillard et al., 2017). The approach also has the potential to challenge ageism attitudes, promote empowerment among older people in the context of social isolation (Ray, 2007 as cited in Buffel, 2018). This will help to promote civic and social participation among the older people in the neighborhood and improve their physical well-being by keeping them active, stimulating their mind and senses while having a space free from other responsibilities (Remillard et al., 2017).

Active Ageing Through Co-Design

A research project conducted by Buffel (2018) explores the idea of a partnership with older people volunteers as co-researchers and collaborators in Manchester with the aim of improving the age-friendliness of their community. The older people as research partners were trained to take the leading role in conducting interviews, develop strategies with other stakeholders to help marginalised groups of older people who are experiencing issues such as social isolation, exclusion, poverty, or health problems from their community (Buffel, 2018). The research highlighted that giving older people the opportunity to be trained as independent co-researchers helped them to put their skills, knowledge, and views of their community into good use. As both the interviewers and interviewees are of a similar age, it makes it easier for both sides to communicate, empathise and engage with each other thus producing informative analysis.

Despite opportunities, the study also faced challenges associated with the public as co-researchers, one of which was the risk of creating a further divide between the more advantaged groups of older people to their peers that might instead disempower the less-advantaged group (Buffel, 2018). This was evident when the interviewers offered ‘solutions’ to get involved in local services and activities to tackle the interviewee’s issue of being isolated from other generations and families. These ‘solutions’ can be seen as imposing the co-researchers’ ‘ideal’ of ‘successful active ageing’ onto the interviewee, creating a difference in power and unintended tensions (Remillard et al., 2017) However, it is important to note it is a crucial starting point in initiating the process of involving older people in discussions of active ageing lifestyle as the volunteers can act as bridges between the marginalised groups of older people and the organisation. This model moves away from retirement communities like Sun City Arizona where older adults are mainly participants and do not contribute to the infrastructure that supports their lifestyle, and as such, potentially missing out on constructive social value between older people and their service providers.

A research project conducted by Buffel (2018) explores the idea of a partnership with older people volunteers as co-researchers and collaborators in Manchester with the aim of improving the age-friendliness of their community. The older people as research partners were trained to take the leading role in conducting interviews, develop strategies with other stakeholders to help marginalised groups of older people who are experiencing issues such as social isolation, exclusion, poverty, or health problems from their community (Buffel, 2018). The research highlighted that giving older people the opportunity to be trained as independent co-researchers helped them to put their skills, knowledge, and views of their community into good use. As both the interviewers and interviewees are of a similar age, it makes it easier for both sides to communicate, empathise and engage with each other thus producing informative analysis.

Despite opportunities, the study also faced challenges associated with the public as co-researchers, one of which was the risk of creating a further divide between the more advantaged groups of older people to their peers that might instead disempower the less-advantaged group (Buffel, 2018). This was evident when the interviewers offered ‘solutions’ to get involved in local services and activities to tackle the interviewee’s issue of being isolated from other generations and families. These ‘solutions’ can be seen as imposing the co-researchers’ ‘ideal’ of ‘successful active ageing’ onto the interviewee, creating a difference in power and unintended tensions (Remillard et al., 2017) However, it is important to note it is a crucial starting point in initiating the process of involving older people in discussions of active ageing lifestyle as the volunteers can act as bridges between the marginalised groups of older people and the organisation. This model moves away from retirement communities like Sun City Arizona where older adults are mainly participants and do not contribute to the infrastructure that supports their lifestyle, and as such, potentially missing out on constructive social value between older people and their service providers.

Conclusion

Ageism is an issue at risk of growing along with the ageing population across the globe. With societies that glorify youth, these prejudices have long been ingrained within our community which has created many misconceptions around older adults which can affect their mental and physical well-being and perceptions of themselves. However, these social stigmas are hard to change. Instead, we can provide spaces or programs that empower older people to be ‘active’ within their communities by contributing their skills and knowledge, and enacting their personal choice, which influences their sense of purpose and achievement.

About the Authors

|

Ye Zhang is Senior Lecturer and Director of the Master of Arts in Urban Design (MAUD) Programme at the National University of Singapore. His research interest is on urban transformation and space-sharing practice. He published widely in the field including a recent co-authored book, Sharing by Design (2020).

|

References

Baum, C. (2018). The ugly truth about ageism: it’s a prejudice targeting our future selves. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/sep/14/the-ugly-truth-about- ageism-its-a-prejudice-targeting-our-future-selves

Buffel, T. (2018). Social research and co-production with older people: Developing age-friendly communities, Journal of Aging Studies, 44, 52-60.

Buffel, T, Phillipson, S, Schard, T. (2012). Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’ cities. Sage Journals: Critical Social Policy, 32:4, DOI 10.1177/026118311430457, 32(4) 597-617

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Loneliness and Social Isolation Linked to Serious

Health Conditions. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/publications/features/lonely-older-adults.html#:~:text=Older%20adults%20are%20at%20increased,the%20amount%20of%20social%20contact.

Cozza, M. (2019). Design and Social Innovation in an Ageing Society. Retrieved from: https://criticalgerontology.com/design-and-social-innovation/

Fernandez, R, Marie, J, Walker, A & Kalache, A (2013). Active Aging: A lobal Goal. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, vol 2013, Article ID 298012, Retrieved from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/cggr/2013/298012/

Genki Kaki. (2020). Don’t Baby Me- Fortune Favours the Brave. Lien Foundation. Episode 6. Retrieved from: http://www.genkikaki.com/episodes/6/1

Greedy, E. (2020). Older workers seen as costly and unproductive in the workplace. Retrieved from: https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/content/news/older-workers-seen-as-costly-and-unproductive-in-the-workplace

Johnson, S. (2015). How can older people play a bigger role in society? Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/mar/30/how-why-older-people-valued-knowledge-experience

Lee, E. (2019). South China Morning Post. Social Enterprise helps senior citizens in Hong Kong to start new careers in its restaurants. Retrieved from: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/3011124/social-enterprise-helps-senior-citizens-hong-kong-start-new

Li, A. (2016). Time Out. Joyce Mak of Gingko House on social entrepreneurship in Hong Kong. Retrieved from: https://www.timeout.com/hong-kong/blog/joyce-mak-of-gingko-house-on-social-entrepreneurship-in-hong-kong-090216

Ministry of Health Singapore. (2020). Active Ageing in the Golden Age. Retrieved from:

https://www.healthhub.sg/live-healthy/892/embracing-the-golden-age

Murray, R. , Caulier, J. , Mulgan, G. (2010). The Young Foundation. The Open Book of Social Innovation. The social innovator series: Ways to design, develop and grow social innovation. Retrieved from: https://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/The-Open-Book-of-Social-Innovationg.pdf

Manzini, E. (2015). Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. London, England: The MIT Press

Osborne, J,W. (2012). Psychological Effects of the Transition to Retirement. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 46:1, 45-58, ISSN 0826-3893, Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ969555.pdf

Remillard, S,B, Buffel, T & Phillipson, C. (2017). Involving Older Residents in Age-Friendly Developments: From Information to Coprouction Mechanisms. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 31:2,146-158, DOI: 10.1080/02763893.2017.1309932.

Schloredt, V. (2019). How Capitalism exploits our fear of old age. Retrieved from: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/transformation/how-capitalism-exploits-our-fear-old-age/

Simpson, D. (2015). Young-Old Urban Utopias of an Ageing Society. Netherlands: Lars Muller Publishers. ISBN 978-3-03778-350-4

Singh, A & Misra, N. (2009). Loneliness, depression and sociability in old age. Industrial Psychiatry Journal of India, 18(1): 51-55, DOI 10.4103/0972-6748.57861.

Tai, J. , Seow, B.Y. (2016). The Straits Times. Elderly ‘earn’ rehab credits for treats at daycare centre. Retrieved from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/elderly-earn-rehab-credits-for-treats-at-daycare-centre

Varsity (2017). Hong Kong Free Press. Gingko House: Where hiring seniors is good for employees, customers and business. Retrieved from: https://hongkongfp.com/2017/04/22/gingko-house-hiring-seniors-good-employees-customers-business/

World Health Organisation (2015). Misconceptions on ageing and health. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news-room/photo-story/photo-story-detail/ageing-and-life-course

World Health Organisation (2007). Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide. Switzerland. WHO Press. ISBN 978 92 4 154730 7. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf

Buffel, T. (2018). Social research and co-production with older people: Developing age-friendly communities, Journal of Aging Studies, 44, 52-60.

Buffel, T, Phillipson, S, Schard, T. (2012). Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’ cities. Sage Journals: Critical Social Policy, 32:4, DOI 10.1177/026118311430457, 32(4) 597-617

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Loneliness and Social Isolation Linked to Serious

Health Conditions. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/publications/features/lonely-older-adults.html#:~:text=Older%20adults%20are%20at%20increased,the%20amount%20of%20social%20contact.

Cozza, M. (2019). Design and Social Innovation in an Ageing Society. Retrieved from: https://criticalgerontology.com/design-and-social-innovation/

Fernandez, R, Marie, J, Walker, A & Kalache, A (2013). Active Aging: A lobal Goal. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, vol 2013, Article ID 298012, Retrieved from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/cggr/2013/298012/

Genki Kaki. (2020). Don’t Baby Me- Fortune Favours the Brave. Lien Foundation. Episode 6. Retrieved from: http://www.genkikaki.com/episodes/6/1

Greedy, E. (2020). Older workers seen as costly and unproductive in the workplace. Retrieved from: https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/content/news/older-workers-seen-as-costly-and-unproductive-in-the-workplace

Johnson, S. (2015). How can older people play a bigger role in society? Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/mar/30/how-why-older-people-valued-knowledge-experience

Lee, E. (2019). South China Morning Post. Social Enterprise helps senior citizens in Hong Kong to start new careers in its restaurants. Retrieved from: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/3011124/social-enterprise-helps-senior-citizens-hong-kong-start-new

Li, A. (2016). Time Out. Joyce Mak of Gingko House on social entrepreneurship in Hong Kong. Retrieved from: https://www.timeout.com/hong-kong/blog/joyce-mak-of-gingko-house-on-social-entrepreneurship-in-hong-kong-090216

Ministry of Health Singapore. (2020). Active Ageing in the Golden Age. Retrieved from:

https://www.healthhub.sg/live-healthy/892/embracing-the-golden-age

Murray, R. , Caulier, J. , Mulgan, G. (2010). The Young Foundation. The Open Book of Social Innovation. The social innovator series: Ways to design, develop and grow social innovation. Retrieved from: https://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/The-Open-Book-of-Social-Innovationg.pdf

Manzini, E. (2015). Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. London, England: The MIT Press

Osborne, J,W. (2012). Psychological Effects of the Transition to Retirement. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 46:1, 45-58, ISSN 0826-3893, Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ969555.pdf

Remillard, S,B, Buffel, T & Phillipson, C. (2017). Involving Older Residents in Age-Friendly Developments: From Information to Coprouction Mechanisms. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 31:2,146-158, DOI: 10.1080/02763893.2017.1309932.

Schloredt, V. (2019). How Capitalism exploits our fear of old age. Retrieved from: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/transformation/how-capitalism-exploits-our-fear-old-age/

Simpson, D. (2015). Young-Old Urban Utopias of an Ageing Society. Netherlands: Lars Muller Publishers. ISBN 978-3-03778-350-4

Singh, A & Misra, N. (2009). Loneliness, depression and sociability in old age. Industrial Psychiatry Journal of India, 18(1): 51-55, DOI 10.4103/0972-6748.57861.

Tai, J. , Seow, B.Y. (2016). The Straits Times. Elderly ‘earn’ rehab credits for treats at daycare centre. Retrieved from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/elderly-earn-rehab-credits-for-treats-at-daycare-centre

Varsity (2017). Hong Kong Free Press. Gingko House: Where hiring seniors is good for employees, customers and business. Retrieved from: https://hongkongfp.com/2017/04/22/gingko-house-hiring-seniors-good-employees-customers-business/

World Health Organisation (2015). Misconceptions on ageing and health. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news-room/photo-story/photo-story-detail/ageing-and-life-course

World Health Organisation (2007). Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide. Switzerland. WHO Press. ISBN 978 92 4 154730 7. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf