|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2020:6; 2

|

EDITORIAL: COVID-19 PERSPECTIVES

Design and Contagion: well-being and the physical environment during the COVID-19 pandemic

Nélida Quintero

American Psychological Association and UD/MH Fellow

American Psychological Association and UD/MH Fellow

Historically, epidemics and public health crises have often influenced design approaches. For instance, Florence Nightingale's observations on the connection of fresh air and hygienic environments changed the design of clinics and hospitals (Chayka, 2020) while Hausmann’s renovation of 1800s Paris and London’s infrastructure redesign both aimed to improve sewers and supply clean water in response to the cholera epidemics of 1832 and 1854 (Giacobbe, 2020; Lewis, 2020). The stark white and spare aesthetic of modernism was partly generated by a concern with infection and tuberculosis (Chayka, 2020), just as an expansion and strengthening of digital infrastructure could be a likely consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic (Klaus, 2020).

Modernism’s emphasis on light, air and sun, together with arguments to promote health and hygiene through changes in the built environment, were used to support late nineteenth-century proposals for housing reform (Start & Stones, 2019), as they were believed to provide the best treatment for tuberculosis infection (Yuko, 2018). Modernist flat roofs had also the advantage of providing space for healthful outdoor activities. The life envisioned to be housed in modernist architecture was seen as having the potential to help combat other social and moral ailments perceived to be tied to crowded urban centers (Yuko, 2018). Furnished with a hand sink, architect Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye entry way possibly served to underline the hygiene and health-oriented values of its inhabitants.

Modernism’s emphasis on light, air and sun, together with arguments to promote health and hygiene through changes in the built environment, were used to support late nineteenth-century proposals for housing reform (Start & Stones, 2019), as they were believed to provide the best treatment for tuberculosis infection (Yuko, 2018). Modernist flat roofs had also the advantage of providing space for healthful outdoor activities. The life envisioned to be housed in modernist architecture was seen as having the potential to help combat other social and moral ailments perceived to be tied to crowded urban centers (Yuko, 2018). Furnished with a hand sink, architect Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye entry way possibly served to underline the hygiene and health-oriented values of its inhabitants.

Figure 1: Sink at the entrance of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye. Image source.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought renewed attention on the interaction of the physical environment and mental and physical health. Without vaccines or treatments, strategies to prevent infection are behavioral and environmental: masks, handwashing, surface disinfection, physical distancing, quarantine, isolation and changes to the built environment that limit physical contact with people and surfaces and enhance natural ventilation (Budds, 2020). The concern with overcrowding and density in cities has regained relevance as a topic of discussion (Basset, 2020; Hamiri, Sabidi & Ewing, 2020). The importance of indoor air quality and benefits of natural ventilation are now the focus of urgent consideration. Heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems, more commonly considered in relationship to energy savings or other trade-focused technical discussions, have come to the forefront in the news, and the once unremarkable option of opening a window is now underlined as a powerful tool for fighting disease (EPA, 2020).

Designers and scientists are diligently developing recommendations to respond to these new environmental conditions and COVID-19-focused needs, such as increasing cross-ventilation, staying outdoors when possible, wearing masks, disinfecting surfaces and designing shared spaces that allow and remind people to stay a safe distance apart (this varies depending on local policy and circumstance) and that provide easy access to hand washing and disinfecting stations.

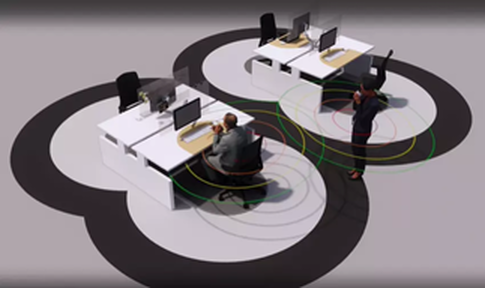

A focus on avoiding contaminated air and surfaces has energized a search for design solutions and technologies that not only emphasize natural ventilation, but that also limit the need to touch people and things, among them touchless technologies, such as automatic doors; cell-phone, voice or motion activated doors, lights and temperature controls, and RFID cards for making purchases (Giacobbe, 2020). Markings everywhere remind us of critical distances; circles around workstations or footprints and arrows on the ground. Physical distancing measures have also included separation through acrylic partitions, separate entrances, and smaller private waiting rooms instead of larger shared spaces (Giacobbe, 2020).

Will the adaptations to the built environment in response to Covid 19 have a lasting impact on urban planning and architectural design? Do such adaptations alter our sense of safety in public and shared space and our sense of well-being?

Designers and scientists are diligently developing recommendations to respond to these new environmental conditions and COVID-19-focused needs, such as increasing cross-ventilation, staying outdoors when possible, wearing masks, disinfecting surfaces and designing shared spaces that allow and remind people to stay a safe distance apart (this varies depending on local policy and circumstance) and that provide easy access to hand washing and disinfecting stations.

A focus on avoiding contaminated air and surfaces has energized a search for design solutions and technologies that not only emphasize natural ventilation, but that also limit the need to touch people and things, among them touchless technologies, such as automatic doors; cell-phone, voice or motion activated doors, lights and temperature controls, and RFID cards for making purchases (Giacobbe, 2020). Markings everywhere remind us of critical distances; circles around workstations or footprints and arrows on the ground. Physical distancing measures have also included separation through acrylic partitions, separate entrances, and smaller private waiting rooms instead of larger shared spaces (Giacobbe, 2020).

Will the adaptations to the built environment in response to Covid 19 have a lasting impact on urban planning and architectural design? Do such adaptations alter our sense of safety in public and shared space and our sense of well-being?

|

Figure 3: A Dutch restaurant has come up with an idea on how to offer classy outdoor dining in the age of coronavirus: small glass cabins built for two or three people, creating intimate cocoons on a public patio. Image source.

|

And for decades, the idea of a distributed, work-at-home workforce has been slowly growing, with much trepidation from companies and managers that are uncertain about how to supervise staff under this novel work model. Yet, in the past six months, many people whose work can be done remotely, have shifted to working from home, with resulting changes to workers' demands of both the home and the urban realm.

|

Figure 4: Brazilian architecture firm Atelier Marko Brajovic in partnership with the agency ℓiⱴε (Live) and Oca Brasil has just launched their new project, HOM, a kind of portable capsule that provides suitable workspace inside the house.

Image source. |

Figure 5: Office desks are likely to change to observe the six-feet rule.Image credit: Cushman & Wakefield, Image source.

|

What are the social and psychological impacts of physical distancing?

Changes necessary to protect physical health and prevent contagion during the COVID-19 pandemic may also have psychological and social consequences. In particular, limiting social interactions can be detrimental to physical and mental health (Bauman & Leary, 1995). Many have made an effort to use the term “physical” distancing over “social” distancing, aware of the psychological benefit of social interactions, especially during a crisis. Social exchanges can take place through virtual technologies -anything from an e-mail to a phone call or a video conferencing application. But can virtual interactions fully replace face-to-face ones? To what extent does the virtual public space experience replicate its counterpart in physical space, and does it reap the same social and psychological benefits?

Other relevant factors such as fear of contagion, worry over associated socio-economic costs, such as changes in personal finances and disruption in the supply chain, as well as stressors associated with self-isolation, may increase psychological distress (Taylor et al, 2020).

How can design address the perception of risk in shared and public space

Perceiving physical separation as safe, and closeness to others as dangerous can be very difficult as people engage with work and public spaces during and after a pandemic. But as offices and businesses reopen, how do we address the fear of sharing indoor spaces outside the home? These spaces not only have to be made as safe as possible from infection spread, but also have to be perceived as safe. Environmental psychology research on the workplace has identified elements that have an impact on mood and well-being, such as sunlight, clean and fresh air and control of the immediate environment to fit a worker’s needs. Suggestions of this kind have been also made to heighten the perception of safety during this pandemic (Rajagopal, 2020).

Can anxiety and fear be minimized in what is perceived as a dangerous and uncontrollable situation? Perceptions of risk vary among individuals, and possibly displaying visible or perceivable contagion-prevention measures in public and shared spaces might also help lessen such perceptions.

For instance, the ability to control aspects of the workplace environment has been shown to increase satisfaction and performance at work, and similarly, during a pandemic, control of natural ventilation, such as operable windows and of other ambient conditions in one’s work area, could potentially diminish the fear of returning to the office.

Environmental psychology research has shown that social and physical environments can influence behavior, finding that conditions that facilitate certain actions, can encourage such actions (Alter, 2013; Thaler, 2009) or influence how a particular environment is perceived. For instance, darker streets might be perceived as more dangerous than better illuminated ones (Alter, 2013). Sinks and disinfecting stations as you enter a shared place, such as a retail store or an office, might emphasize the measures taken to prevent virus spread, at once nudging individual protective behaviors and signaling shared levels of risk concern.

Designers, architects and urban planners’ efforts to address spread through environmental design solutions should keep in mind the psycho-social consequences of social distancing and sheltering in place as well as the perceptions of risk under fear of contagion. While many of us struggle with adapting and living with uncertainty during this pandemic, the design adaptations of shared and public spaces can also help communicate a sense of joint action toward the conditions and behaviors which can be managed and controlled to promote safety and health during the COVID 19 pandemic.

Changes necessary to protect physical health and prevent contagion during the COVID-19 pandemic may also have psychological and social consequences. In particular, limiting social interactions can be detrimental to physical and mental health (Bauman & Leary, 1995). Many have made an effort to use the term “physical” distancing over “social” distancing, aware of the psychological benefit of social interactions, especially during a crisis. Social exchanges can take place through virtual technologies -anything from an e-mail to a phone call or a video conferencing application. But can virtual interactions fully replace face-to-face ones? To what extent does the virtual public space experience replicate its counterpart in physical space, and does it reap the same social and psychological benefits?

Other relevant factors such as fear of contagion, worry over associated socio-economic costs, such as changes in personal finances and disruption in the supply chain, as well as stressors associated with self-isolation, may increase psychological distress (Taylor et al, 2020).

How can design address the perception of risk in shared and public space

Perceiving physical separation as safe, and closeness to others as dangerous can be very difficult as people engage with work and public spaces during and after a pandemic. But as offices and businesses reopen, how do we address the fear of sharing indoor spaces outside the home? These spaces not only have to be made as safe as possible from infection spread, but also have to be perceived as safe. Environmental psychology research on the workplace has identified elements that have an impact on mood and well-being, such as sunlight, clean and fresh air and control of the immediate environment to fit a worker’s needs. Suggestions of this kind have been also made to heighten the perception of safety during this pandemic (Rajagopal, 2020).

Can anxiety and fear be minimized in what is perceived as a dangerous and uncontrollable situation? Perceptions of risk vary among individuals, and possibly displaying visible or perceivable contagion-prevention measures in public and shared spaces might also help lessen such perceptions.

For instance, the ability to control aspects of the workplace environment has been shown to increase satisfaction and performance at work, and similarly, during a pandemic, control of natural ventilation, such as operable windows and of other ambient conditions in one’s work area, could potentially diminish the fear of returning to the office.

Environmental psychology research has shown that social and physical environments can influence behavior, finding that conditions that facilitate certain actions, can encourage such actions (Alter, 2013; Thaler, 2009) or influence how a particular environment is perceived. For instance, darker streets might be perceived as more dangerous than better illuminated ones (Alter, 2013). Sinks and disinfecting stations as you enter a shared place, such as a retail store or an office, might emphasize the measures taken to prevent virus spread, at once nudging individual protective behaviors and signaling shared levels of risk concern.

Designers, architects and urban planners’ efforts to address spread through environmental design solutions should keep in mind the psycho-social consequences of social distancing and sheltering in place as well as the perceptions of risk under fear of contagion. While many of us struggle with adapting and living with uncertainty during this pandemic, the design adaptations of shared and public spaces can also help communicate a sense of joint action toward the conditions and behaviors which can be managed and controlled to promote safety and health during the COVID 19 pandemic.

About the Author

|

Nélida Quintero is an environmental psychologist and licensed architect based in New York. She holds a PhD in Environmental Psychology from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, a Master's in Architecture from Princeton University and a Master's in Fine Arts from Parsons School of Design. She has taught at Hunter College and on the Parsons School of Design Certificate Program, and has designed and managed interior architecture projects in the US and Latin America. She is an American Psychological Association NGO Representative at the United Nations and a Fellow at the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health. Her research interests are broadly focused on the interactions between people, behavior and the physical environment, in particular in relationship to health, well-being, culture, new media and gender.

|

References

Alter, A. L. (2013). Drunk tank pink: And other unexpected forces that shape how we think, feel, and behave. New York: Penguin Press.

Basset, M. (2020, May 15) Just because you can afford to leave the city doesn’t mean you should. The New York Times - Breaking News, World News & Multimedia, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/opinion/sunday/coronavirus-cities-density.html)

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497– 529.

Budds, D. (2020, March 17). Design in the age of pandemics. Curbed. https://www.curbed.com/2020/3/17/21178962/design-pandemics-coronavirus-quarantine

Chayka, K. (2020, June 17). How the coronavirus will reshape architecture. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/dept-of-design/how-the-coronavirus-will-reshape-architecture

Giacobbe, A. (2020, March 18). How the COVID-19 pandemic will change the built environment. Architectural Digest. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/covid-19-design

Hamidi, S., Sabouri, S., & Ewing, R. (2020). Does Density Aggravate the COVID-19 Pandemic? Early Findings and Lessons for Planners. Journal of the American Planning Association, 1-15.

Indoor air in homes and coronavirus (COVID-19). (2020, August 26). US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/coronavirus/indoor-air-homes-and-coronavirus-covid-19

Gurstein, P. (2001). Wired to the world, chained to the home: Telework in daily life. UBC Press.

Klaus, I. (2020, March 6) Pandemics are also an urban planning problem. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-06/how-the-coronavirus-could-change-city-planning

Lewis, M. J. (2020, Jun 08). Life & arts -- cultural commentary: Pandemic as urban planner --- from cholera outbreaks to yellow fever, disease has had a profound impact on the shape of our cities. Wall Street Journal Retrieved from http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/docview/2410068319?accountid=10226

McKinsey & Company (2020, June 29) COVID-19 and the employee experience: How leaders can seize the moment. (2020, June 29) ://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/covid-19-and-the-employee-experience-how-leaders-can-seize-the-moment

Rajagopal, A. (2020, September 1) Driving Culture in a Changing Environment: Lessons Learned from COVID-19, Metropolis Think Tank webinar

Stark, J. F., & Stones, C. (2019). Constructing representations of germs in the twentieth century. Cultural and Social History, 16(3), 287-314.

Thaler, R. & Sunstein, C.(2008) Nudge : Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness New Haven : Yale University Press,

Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Paluszek, M. M., Fergus, T. A., McKay, D., & Asmundson, G. J. (2020). COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and anxiety, 37(8), 706-714.

Yuko, E. (2018, October 30) How the tuberculosis epidemic influenced modernist architecture, Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-30/what-architecture-learned-from-tb-hospitals

Basset, M. (2020, May 15) Just because you can afford to leave the city doesn’t mean you should. The New York Times - Breaking News, World News & Multimedia, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/opinion/sunday/coronavirus-cities-density.html)

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497– 529.

Budds, D. (2020, March 17). Design in the age of pandemics. Curbed. https://www.curbed.com/2020/3/17/21178962/design-pandemics-coronavirus-quarantine

Chayka, K. (2020, June 17). How the coronavirus will reshape architecture. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/dept-of-design/how-the-coronavirus-will-reshape-architecture

Giacobbe, A. (2020, March 18). How the COVID-19 pandemic will change the built environment. Architectural Digest. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/covid-19-design

Hamidi, S., Sabouri, S., & Ewing, R. (2020). Does Density Aggravate the COVID-19 Pandemic? Early Findings and Lessons for Planners. Journal of the American Planning Association, 1-15.

Indoor air in homes and coronavirus (COVID-19). (2020, August 26). US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/coronavirus/indoor-air-homes-and-coronavirus-covid-19

Gurstein, P. (2001). Wired to the world, chained to the home: Telework in daily life. UBC Press.

Klaus, I. (2020, March 6) Pandemics are also an urban planning problem. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-06/how-the-coronavirus-could-change-city-planning

Lewis, M. J. (2020, Jun 08). Life & arts -- cultural commentary: Pandemic as urban planner --- from cholera outbreaks to yellow fever, disease has had a profound impact on the shape of our cities. Wall Street Journal Retrieved from http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/docview/2410068319?accountid=10226

McKinsey & Company (2020, June 29) COVID-19 and the employee experience: How leaders can seize the moment. (2020, June 29) ://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/covid-19-and-the-employee-experience-how-leaders-can-seize-the-moment

Rajagopal, A. (2020, September 1) Driving Culture in a Changing Environment: Lessons Learned from COVID-19, Metropolis Think Tank webinar

Stark, J. F., & Stones, C. (2019). Constructing representations of germs in the twentieth century. Cultural and Social History, 16(3), 287-314.

Thaler, R. & Sunstein, C.(2008) Nudge : Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness New Haven : Yale University Press,

Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Paluszek, M. M., Fergus, T. A., McKay, D., & Asmundson, G. J. (2020). COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and anxiety, 37(8), 706-714.

Yuko, E. (2018, October 30) How the tuberculosis epidemic influenced modernist architecture, Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-30/what-architecture-learned-from-tb-hospitals