Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2020:6;13 (Advance publication 2019)

|

CITY CASE STUDY

|

Washington DC, USA: An Urban Design and Mental Health Case Study

Hana Burkly

Faculty of the Department of Global Health, School of Nursing and Health Sciences, Georgetown University

Faculty of the Department of Global Health, School of Nursing and Health Sciences, Georgetown University

Introduction

When Mayor Vincent Gray launched his Sustainable D.C. initiative in 2011, he proclaimed that he “wanted to make the District the healthiest, greenest, and most livable city in the nation” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Washington, D.C. is certainly on track to become these things, but not all parts of the city are equally healthy, green and livable. This paper aims to look at the city as a whole and as broken down by districts, to understand how geographically, Washington D.C. incorporates healthy design into its urban landscape. The second aim of this paper is to look at the mental health of the population of Washington, D.C. and, wherever possible, break down the mental health statistics by district to get a better understanding of what mental health issues are most prevalent in the city. Finally, this paper will seek to determine if there is any link between the urban design of D.C. and the mental health of its population. This is much easier said than done, as there is limited information on mental health statistics, and varying types of language used to describe mental health-friendly urban design.

It is important to note that as the nation’s capital, Washington D.C.’s land ownership is divided. Some parts of the city are federally owned lands, others are the city’s lands, and much is privately owned. This paper will focus primarily on the lands that are under the control of the D.C. Office of the Mayor, with some focus on the federally owned parks.

The policies of interest for this paper put forth by the Office of the Mayor fall into two categories. Either they explicitly mention mental health, but they do so in the context of mental illness, or they discuss strategies which have an implicit connection to mental health, such as designing greener spaces, encouraging active movement, or supporting an aging population which wishes to be self-supporting. For example, in its Community-Based Mental Health Action Plan for the District’s Youth and Young Adults, the D.C. Department of Mental Health (DMH) commits to “developing a system that supports individuals with mental illness in integrated, community-based settings” (DC Department of Mental Health, 2012), but does not have a similar statement addressing people who do not have explicit mental health needs.

It is important to note that as the nation’s capital, Washington D.C.’s land ownership is divided. Some parts of the city are federally owned lands, others are the city’s lands, and much is privately owned. This paper will focus primarily on the lands that are under the control of the D.C. Office of the Mayor, with some focus on the federally owned parks.

The policies of interest for this paper put forth by the Office of the Mayor fall into two categories. Either they explicitly mention mental health, but they do so in the context of mental illness, or they discuss strategies which have an implicit connection to mental health, such as designing greener spaces, encouraging active movement, or supporting an aging population which wishes to be self-supporting. For example, in its Community-Based Mental Health Action Plan for the District’s Youth and Young Adults, the D.C. Department of Mental Health (DMH) commits to “developing a system that supports individuals with mental illness in integrated, community-based settings” (DC Department of Mental Health, 2012), but does not have a similar statement addressing people who do not have explicit mental health needs.

Methods

This case study was developed using the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health methodology based on the GAPS framework. GAPS stands for Green places, Active places, Pro-social places and Safe places. It was developed with the notion that these types of places have been demonstrated to be beneficial for people's mental health, and that the more components a city has, the better-equipped its population for mental health resilience. This paper will explore the many ways in which spaces can fit into the categories of green, active, pro-social, and safe spaces.

In order to begin to understand the historical and contemporary urban design of Washington, D.C., I spoke with representatives from various departments under the Mayor’s Office, such as the Department of Transportation and the Office of Disability Rights, as well as urban planners who were involved with projects in D.C. From these interviews, I gained the names and contact information of other people who might have relevant information, whom I then contacted. Through these conversations, I developed a more holistic understanding of the city from multiple perspectives, and a solid foundation of the history of D.C.’s urban design. Many of the people I spoke with also recommended specific documents to help me in my understanding of D.C.’s urban design, such as the Comprehensive Plan, which I read and searched through the references for further reading. Finally, I spoke with professors in the urban and regional planning department at the Georgetown University School of Continuing Studies, who provided information and further readings on designing for mental health in Washington, D.C. I then used these readings as a starting point to find further readings. These conversations and readings, collectively, informed my background of Washington, D.C.’s urban design and mental health landscape.

In order to begin to understand the historical and contemporary urban design of Washington, D.C., I spoke with representatives from various departments under the Mayor’s Office, such as the Department of Transportation and the Office of Disability Rights, as well as urban planners who were involved with projects in D.C. From these interviews, I gained the names and contact information of other people who might have relevant information, whom I then contacted. Through these conversations, I developed a more holistic understanding of the city from multiple perspectives, and a solid foundation of the history of D.C.’s urban design. Many of the people I spoke with also recommended specific documents to help me in my understanding of D.C.’s urban design, such as the Comprehensive Plan, which I read and searched through the references for further reading. Finally, I spoke with professors in the urban and regional planning department at the Georgetown University School of Continuing Studies, who provided information and further readings on designing for mental health in Washington, D.C. I then used these readings as a starting point to find further readings. These conversations and readings, collectively, informed my background of Washington, D.C.’s urban design and mental health landscape.

History of urban planning in Washington DC

In 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which authorized a federal district along the Potomac River that would ultimately become Washington, D.C. President George Washington commissioned Pierre L’Enfant, a French-American military engineer and urban planner, to design this new city. L’Enfant devised a master plan for the city, laid out in a gridlike fashion, with wide streets, large open spaces for public gatherings, and impressive monuments and buildings. At the center of the plan would be a 400-foot-wide “grand avenue,” which later became the National Mall. He envisioned people mingling on this grand avenue and participating in civil discourse (Fletcher, 2008).

In 1901, the U.S. Senate created the McMillian Commission, which used L’Enfant’s original city plan as a basis for the final design implementation of Washington, D.C. The commission was responsible for the planning of the system of parks that is in D.C. today. When construction began, much of the area was swampland and farmland (Gray, Urban design and mental health in Washington, D.C., 2018). Workers had to clear the land for the Mall and drain the swamp (Fletcher, 2008).

D.C. was designed to mirror a vision of a prosperous and growing country. When the streets were built, they had to take into account the natural topography and vistas, making sure that the views were broad enough to see the large monuments around the city. The greatest emphasis was placed on the National Mall and the area surrounding it. The original planners did an excellent job of creating the heart of the city, but as the city expanded and different populations moved in and out, the same level of care was not taken to develop and beautify the rest of it. As a result, the challenge facing urban planners today is to put the same level of care into the surrounding neighborhoods (DC Office of Planning, 2011).

In 1901, the U.S. Senate created the McMillian Commission, which used L’Enfant’s original city plan as a basis for the final design implementation of Washington, D.C. The commission was responsible for the planning of the system of parks that is in D.C. today. When construction began, much of the area was swampland and farmland (Gray, Urban design and mental health in Washington, D.C., 2018). Workers had to clear the land for the Mall and drain the swamp (Fletcher, 2008).

D.C. was designed to mirror a vision of a prosperous and growing country. When the streets were built, they had to take into account the natural topography and vistas, making sure that the views were broad enough to see the large monuments around the city. The greatest emphasis was placed on the National Mall and the area surrounding it. The original planners did an excellent job of creating the heart of the city, but as the city expanded and different populations moved in and out, the same level of care was not taken to develop and beautify the rest of it. As a result, the challenge facing urban planners today is to put the same level of care into the surrounding neighborhoods (DC Office of Planning, 2011).

Geography and demographics of Washington DC

Washington D.C. is surrounded by the states of Maryland to the northeast and Virginia on the southwest. It covers 68 square miles. At its center, it is mostly flat, with low hills to the north and south. The Potomac river separates D.C. from Virginia, and the Anacostia river runs through the eastern section (World Atlas, 2012).

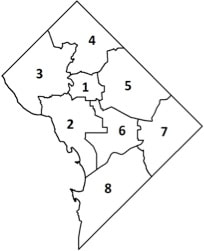

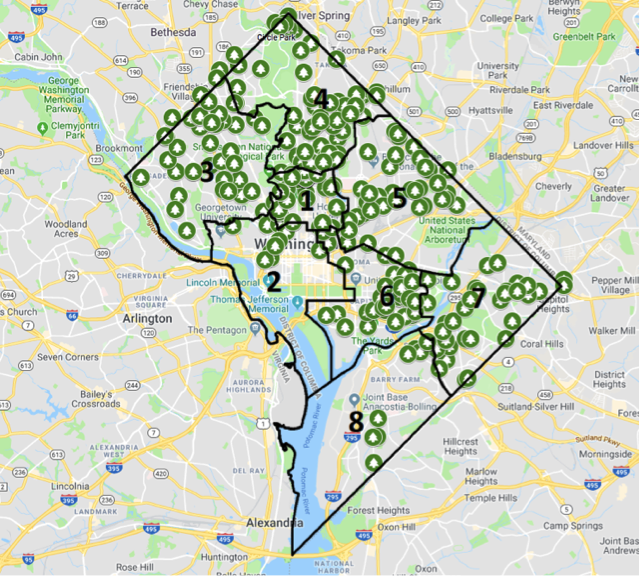

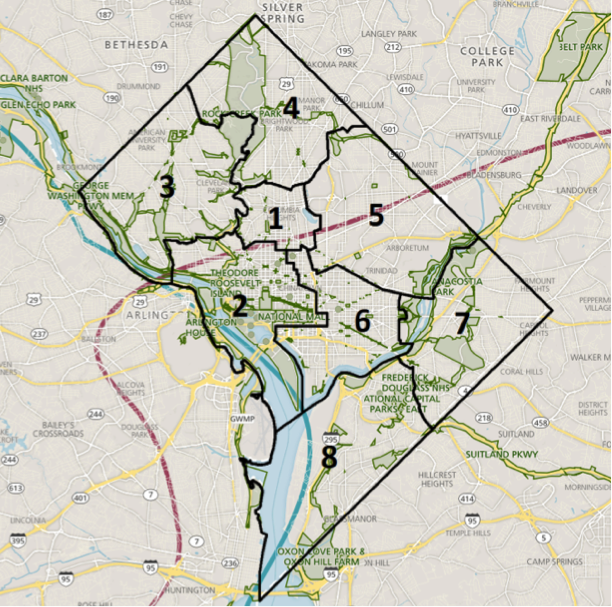

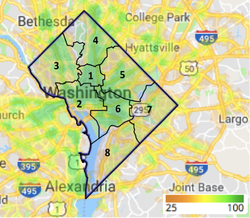

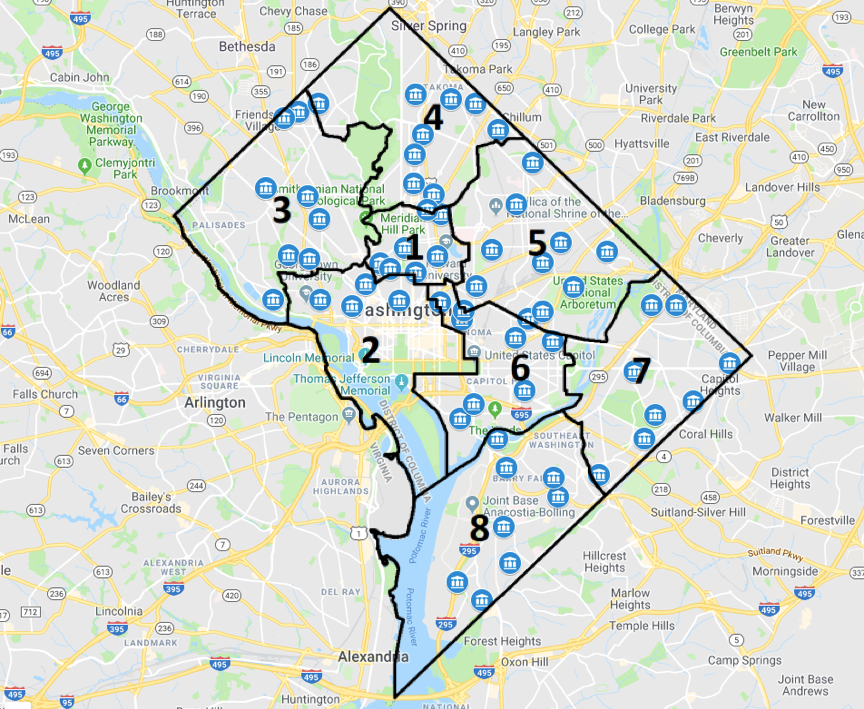

Washington D.C. is divided into 8 wards (Figure 2). Historically, the Anacostia River has been a marker of a significant socioeconomic divide, though the demographics of the populations within each ward have also been distinct from one another. The area of land that is now much of Ward 8 was farmland during the time that the National Mall was being built. It was one of the first suburbs of D.C., founded in 1854 (Office of the Mayor, 2017).

Washington D.C. is divided into 8 wards (Figure 2). Historically, the Anacostia River has been a marker of a significant socioeconomic divide, though the demographics of the populations within each ward have also been distinct from one another. The area of land that is now much of Ward 8 was farmland during the time that the National Mall was being built. It was one of the first suburbs of D.C., founded in 1854 (Office of the Mayor, 2017).

Figure 2: Map of D.C. by ward. Source: D.C. Office of Planning.

Throughout D.C.’s history, the greatest emphasis has always been placed on beautifying and developing the heart of the city, to the West of the Anacostia. As a result, the National Mall has become a widely recognized landmark of D.C. These efforts have often times pushed aside efforts to make similar improvements to the infrastructure of Wards 7 and 8, to the East of the Anacostia, creating inequity in investment in D.C.’s urban design.

In the past decade, the demographics of several neighborhoods have changed significantly. Shaw, Bloomingdale, and Navy Yard, in Wards 1, 5 and 6 respectively, are prime examples, having all experienced a major influx of working-aged adults, new infrastructure, job creation, and economic growth. However, one negative side effect of these positive social and economic gains has been the gentrification of these areas, with the original residents often being pushed out by rent increases and higher cost of living (NPR, 2017). This displacement of long term residents, many of whom grew up in the surrounding neighborhoods and have strong ties to the larger community as a whole through institutions such as school, church and extended family networks, could also result in a loss of social capital, leading to fewer “eyes on the street” who know what to look for.

Perhaps no region of D.C. has seen more rapid demographic change than Navy Yard. Located in Ward 6 in Southeast D.C., it is bordered by the Anacostia River on its southern border. From 2006 to 2015, the proportion of White residents in Navy Yard increased by 29 percent, the proportion of households earning over $100,000 increased by 18 percent, and the proportion of residents aged 22 to 34 increased by 15 percent (DataLensDC, 2017). These sociodemographic developments are examples of how parts of the city can rapidly change in a matter of years, changing the very landscape of those areas.

Currently, the population of Washington D.C. is 47.1% Black or African American, 36.8% White (non-Hispanic), 11.0% Hispanic, 4.3% Asian, 0.6% American Indian or Alaska Native, and 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (United States Census Bureau, 2017). In 2017, Washington D.C. had a population of 693,972. This was the highest it had been in four decades, largely due to the high yearly influx of new residents. These have primarily been White, working-age adults earning high incomes. However, the new residents have not moved into all parts of D.C.. Rather, there has been a trend in a change in proportion of White residents within certain wards and not others. Furthermore, gentrification of what had been primarily Black neighborhoods has also changed the demographics of the wards over the years. From 2006 to 2015, D.C.’s central and Northeastern neighborhoods experienced an influx in White, wealthy, working-age residents, while proportions of White residents decreased along the western edge of the city, West of Rock Creek Park and East of the Anacostia River (DataLensDC, 2017).

During the same period, household incomes rose in almost every district, with especially high increases in the center of the city, such as Navy Yard and the Shaw and Howard University neighborhood clusters. East of the Anacostia River, several neighborhoods experienced a decrease in households earning over $100,000 a year. The overall picture is that in many neighborhoods that were already very high income, income continued to rise, while in areas with smaller proportions of high income earners experienced a further decline in wealth.

In the past decade, the demographics of several neighborhoods have changed significantly. Shaw, Bloomingdale, and Navy Yard, in Wards 1, 5 and 6 respectively, are prime examples, having all experienced a major influx of working-aged adults, new infrastructure, job creation, and economic growth. However, one negative side effect of these positive social and economic gains has been the gentrification of these areas, with the original residents often being pushed out by rent increases and higher cost of living (NPR, 2017). This displacement of long term residents, many of whom grew up in the surrounding neighborhoods and have strong ties to the larger community as a whole through institutions such as school, church and extended family networks, could also result in a loss of social capital, leading to fewer “eyes on the street” who know what to look for.

Perhaps no region of D.C. has seen more rapid demographic change than Navy Yard. Located in Ward 6 in Southeast D.C., it is bordered by the Anacostia River on its southern border. From 2006 to 2015, the proportion of White residents in Navy Yard increased by 29 percent, the proportion of households earning over $100,000 increased by 18 percent, and the proportion of residents aged 22 to 34 increased by 15 percent (DataLensDC, 2017). These sociodemographic developments are examples of how parts of the city can rapidly change in a matter of years, changing the very landscape of those areas.

Currently, the population of Washington D.C. is 47.1% Black or African American, 36.8% White (non-Hispanic), 11.0% Hispanic, 4.3% Asian, 0.6% American Indian or Alaska Native, and 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (United States Census Bureau, 2017). In 2017, Washington D.C. had a population of 693,972. This was the highest it had been in four decades, largely due to the high yearly influx of new residents. These have primarily been White, working-age adults earning high incomes. However, the new residents have not moved into all parts of D.C.. Rather, there has been a trend in a change in proportion of White residents within certain wards and not others. Furthermore, gentrification of what had been primarily Black neighborhoods has also changed the demographics of the wards over the years. From 2006 to 2015, D.C.’s central and Northeastern neighborhoods experienced an influx in White, wealthy, working-age residents, while proportions of White residents decreased along the western edge of the city, West of Rock Creek Park and East of the Anacostia River (DataLensDC, 2017).

During the same period, household incomes rose in almost every district, with especially high increases in the center of the city, such as Navy Yard and the Shaw and Howard University neighborhood clusters. East of the Anacostia River, several neighborhoods experienced a decrease in households earning over $100,000 a year. The overall picture is that in many neighborhoods that were already very high income, income continued to rise, while in areas with smaller proportions of high income earners experienced a further decline in wealth.

Leadership for health in the city

Muriel Bowser took office as the mayor of Washington D.C. in 2015. She was preceded by Mayor Vincent Gray, who was in office from 2011 to 2015. Mayor Gray put forth a multitude of ideas for the improvement of the infrastructure for health in D.C., most of which were described in his Sustainable D.C. Plan. The priority challenges discussed in this plan were jobs and the economy; health and wellness; equity and diversity; and climate and the environment (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). This plan continues to be implemented and updated under Mayor Bowser, and will be used throughout this paper

Mental health in Washington DC

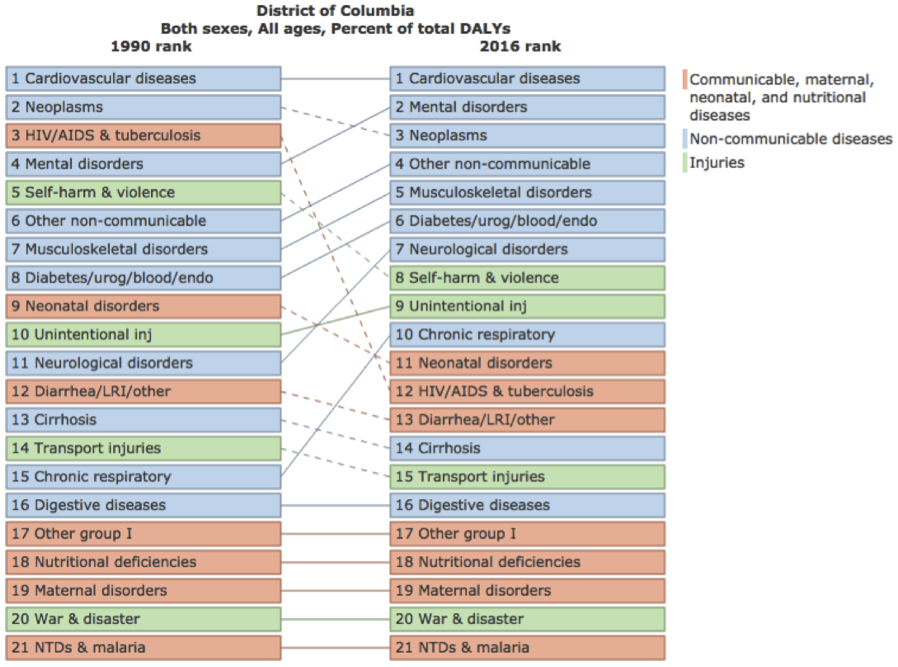

Mental health and substance use disorders are the second leading cause of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in D.C., after cardiovascular diseases (Figure 3). Fifteen percent of total DALYs in D.C. are caused by mental health and substance use disorders, and this number is on the rise (University of Washington, 2018). Between 1990 and 2016, DALYs attributable to mental health and substance use disorders increased by 75% (University of Washington, 2018).

The demographics of Washington D.C. are changing, and with those changes come shifts in the burden of disease. The last decade has seen a steady increase in the proportion of the population that is of working age. Among 15-49 year-olds in D.C. (which account for the largest proportion of the population, mean age 33.8), mental health disorders are the number one cause of DALYs, accounting for 29.57% of total DALYs.

The demographics of Washington D.C. are changing, and with those changes come shifts in the burden of disease. The last decade has seen a steady increase in the proportion of the population that is of working age. Among 15-49 year-olds in D.C. (which account for the largest proportion of the population, mean age 33.8), mental health disorders are the number one cause of DALYs, accounting for 29.57% of total DALYs.

Figure 3: District of Columbia burden of disease information. Source: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/

In 2018, an organization called Mental Health America created a “State of Mental Health” document for the United States, broken down by state. The document shows the prevalence of mental illness in the United States. The data collected were grouped into the following categories: Adults with Any Mental Illness (AMI); adults with dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol; adults with serious thoughts of suicide; youth with at least one past year major depressive episode (MDE); youth with dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol; and youth with severe depression (2017 state of mental health in America - Prevalence data, 2018). This document is one of the only comprehensive analyses of prevalence of mental illness in the U.S. broken down by state. In order to have an understanding of what Washington D.C.’s primary burden of mental illness lies, and to see how it compares to the nation, an in-depth analysis and summary of the document is necessary.

First, it is important to define the terms used in the “State of Mental Health” document. Adults with Any Mental Illness (AMI) is defined by SAMHSA as “having a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder, other than a developmental or substance use disorder” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016). These can range from mild to severe. Adults with dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol includes those dependent on “marijuana/hashish, cocaine (including crack), heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, or prescription-type psychotherapeutics used non-medically” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013). When referring to youth with at least one past year major depressive episode (MDE), a major depressive episode is characterized by two or more weeks of feeling depressed, losing interest or pleasure in daily activities, and having difficulty sleeping, eating or concentrating (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016). Adults with serious thoughts of suicide is measured on an as-reported basis. Finally, youth with severe depression are identified as those who report experiencing difficulties in school, home and in relationships (2017 state of mental health in America - Prevalence data, 2018).

For the “State of Mental Health” rankings, the numbers range from 1 to 51 (reflecting the 50 states plus the District of Columbia). Higher numbers indicate worse outcomes. D.C. ranks 30th in terms of adults with AMI. 102,000 people, or 19.32% of the population, have any mental illness. This is slightly higher than the national average of 18.29% (43.7 million Americans). D.C. ranks the worst in terms of dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol, in 51st (last) place. The prevalence of dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol is 12.51% in D.C., as compared to 8.47% nationally. That translates to 66,000 people in D.C. The District ranks 16th in terms of adults with serious thoughts of suicide, with 3.91% having seriously contemplated suicide, or 21,000 people. This is about the same as the national average of 3.94%.

The percentage of youth reporting at least one past year major depressive episode in the past year across the United States has been increasing. D.C. has the lowest prevalence, at 8.69%, or 3,000 youth, as compared to the national average of 11.01%. However, it is certainly possible that a percentage of depressed youth go undiagnosed and untreated, especially in lower socioeconomic settings, where fewer resources are available.

D.C. ranks 3rd in terms of its percentage of youth who have reported a severe major depressive episode, with 5.5% prevalence (2,000 people), as compared to a national prevalence of 7.4%. However, the District ranks 41st in terms of youth with dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol. Currently, 5.63% of youth in D.C., or 2,000 people, struggle with alcohol or drug problems, compared to the national average of 5.13% (2017 state of mental health in America - Prevalence data, 2018).

In sum, as compared to national averages, D.C. ranks the worst in terms of dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol among both adults and youth. D.C. also has a worryingly high proportion of its population of adults with any mental illness. To further complicate the problem, it is important to note that mental illness is difficult to track and measure because most of the time, mental health issues are not visible on the outside and the data are mostly based on self-reported measures. So, these numbers could be far off from the actual numbers of people in D.C. with these health conditions.

Depression by Ward

There is not very much data available for mental health statistics in D.C. on a by-ward basis. However, D.C. does participate in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), an annual, nationwide survey conducted over the phone that collects health data from residents in the fifty states and the District of Columbia (CDC, 2018). Results of those screenings in D.C. can be broken down by ward. The 2015 BRFSS screened for adults who had been previously diagnosed with a depressive disorder and found that 18% of D.C. residents had been diagnosed at some point in their lives (DC Department of Health, 2015).

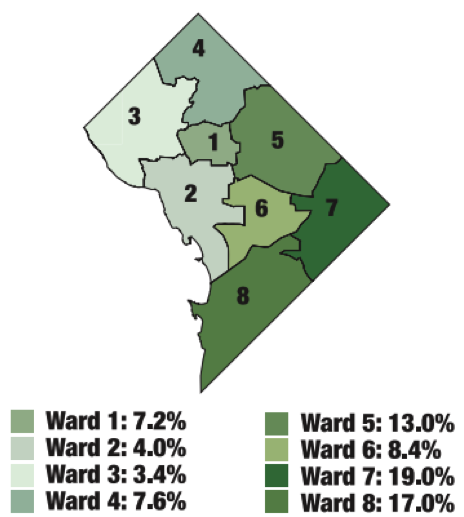

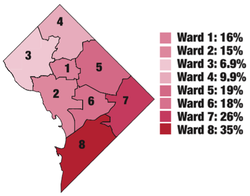

When broken down by Ward, however, there were significant disparities, with 15.9-16.2% of residents in Wards 1 and 4 reporting having been diagnosed with a depressive disorder while 22.5-25.9% of residents in Ward 8 reporting having been diagnosed. These numbers are particularly striking considering that Ward 8 has the lowest access to primary care physicians who would make the diagnosis, and that even though White residents are slightly more likely to have been diagnosed with a depressive disorder than Black residents (19.4% vs. 18.7%, respectively), Ward 8, which is 92.8% Black, still had the highest rates of adults who were diagnosed with a depressive disorder (DC Department of Health, 2015). Figure 4 demonstrates diagnosis of a depressive disorder in adults by ward.

Depression diagnosis only tells a fraction of the story. Mental Health America also conducted a screening of depression in 2017 using phone interviews to survey a representative sample of participants from the 50 states and D.C. In addition to being asked whether they had been diagnosed with a depressive disorder, respondents were also given the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression screen which measures depressive symptoms. Respondents could then be categorized as having minimal, mild, moderate, moderately severe, or severe depression. Startlingly, 70% of respondents who had moderately severe and severe depression according to the screen reported never having been diagnosed by a medical professional (Mental Health America, 2017). This statistic demonstrates that the numbers obtained through looking solely at diagnosed cases are most likely a gross understatement of the true burden of mental illness.

Homelessness and Mental Health

Aside from the “State of Mental Health” and BRFSS data, little is known about per-state or -city mental health. However, there are proxies which can serve as indicators of mental health more generally. Homelessness is one such indicator.

Homelessness and poor mental health are closely tied. It is difficult to know what the general population’s mental health outcomes are because many people often go undiagnosed, but the population of people experiencing homelessness can sometimes serve as a proxy for the severest of cases since having a severe mental illness can make it difficult to keep a job and perform other functions necessary for keeping a home, thus leading many people with mental illness to eventually become homeless. By some estimates, between 30 and 50% of people experiencing homelessness have a severe mental illness, mainly psychoses, acute anxiety and personality disorders (Scott, 2018). Substance abuse comorbidities, such as alcohol or drug dependence, may be as high as 70% among the homeless (Salkow & Manfred, 2003). Homelessness then further exacerbates mental illness, as people are left feeling powerless and robbed of their dignity (Burn, 1992). This becomes a vicious cycle that keeps people on the streets instead of getting them treatment to break the cycle of homelessness.

One of Mayor Bowser’s priorities was to close down D.C. General, D.C.’s main homeless shelter, and replace it with smaller shelters, one in each ward. However, things did not go as planned and although D.C. General shut down, the new shelters were not opened in time, leaving many on the streets (Murphy & Tseu, 2018). Homelessness is not equally distributed across the wards of D.C. Unemployment, a risk factor for becoming homeless, is 17% in Ward 8 and 19% in Ward 7. In comparison, it is 4% in Ward 2 and 3.4% in Ward 3 (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Poverty, another factor which is closely correlated to homelessness, is similarly divided among wards. 35% of Ward 8 residents and 26% of Ward 7 residents live in poverty. In contrast, 6.9% of residents in Ward 3 and 9.9% of residents in Ward 4 live in poverty.

First, it is important to define the terms used in the “State of Mental Health” document. Adults with Any Mental Illness (AMI) is defined by SAMHSA as “having a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder, other than a developmental or substance use disorder” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016). These can range from mild to severe. Adults with dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol includes those dependent on “marijuana/hashish, cocaine (including crack), heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, or prescription-type psychotherapeutics used non-medically” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013). When referring to youth with at least one past year major depressive episode (MDE), a major depressive episode is characterized by two or more weeks of feeling depressed, losing interest or pleasure in daily activities, and having difficulty sleeping, eating or concentrating (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016). Adults with serious thoughts of suicide is measured on an as-reported basis. Finally, youth with severe depression are identified as those who report experiencing difficulties in school, home and in relationships (2017 state of mental health in America - Prevalence data, 2018).

For the “State of Mental Health” rankings, the numbers range from 1 to 51 (reflecting the 50 states plus the District of Columbia). Higher numbers indicate worse outcomes. D.C. ranks 30th in terms of adults with AMI. 102,000 people, or 19.32% of the population, have any mental illness. This is slightly higher than the national average of 18.29% (43.7 million Americans). D.C. ranks the worst in terms of dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol, in 51st (last) place. The prevalence of dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol is 12.51% in D.C., as compared to 8.47% nationally. That translates to 66,000 people in D.C. The District ranks 16th in terms of adults with serious thoughts of suicide, with 3.91% having seriously contemplated suicide, or 21,000 people. This is about the same as the national average of 3.94%.

The percentage of youth reporting at least one past year major depressive episode in the past year across the United States has been increasing. D.C. has the lowest prevalence, at 8.69%, or 3,000 youth, as compared to the national average of 11.01%. However, it is certainly possible that a percentage of depressed youth go undiagnosed and untreated, especially in lower socioeconomic settings, where fewer resources are available.

D.C. ranks 3rd in terms of its percentage of youth who have reported a severe major depressive episode, with 5.5% prevalence (2,000 people), as compared to a national prevalence of 7.4%. However, the District ranks 41st in terms of youth with dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol. Currently, 5.63% of youth in D.C., or 2,000 people, struggle with alcohol or drug problems, compared to the national average of 5.13% (2017 state of mental health in America - Prevalence data, 2018).

In sum, as compared to national averages, D.C. ranks the worst in terms of dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol among both adults and youth. D.C. also has a worryingly high proportion of its population of adults with any mental illness. To further complicate the problem, it is important to note that mental illness is difficult to track and measure because most of the time, mental health issues are not visible on the outside and the data are mostly based on self-reported measures. So, these numbers could be far off from the actual numbers of people in D.C. with these health conditions.

Depression by Ward

There is not very much data available for mental health statistics in D.C. on a by-ward basis. However, D.C. does participate in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), an annual, nationwide survey conducted over the phone that collects health data from residents in the fifty states and the District of Columbia (CDC, 2018). Results of those screenings in D.C. can be broken down by ward. The 2015 BRFSS screened for adults who had been previously diagnosed with a depressive disorder and found that 18% of D.C. residents had been diagnosed at some point in their lives (DC Department of Health, 2015).

When broken down by Ward, however, there were significant disparities, with 15.9-16.2% of residents in Wards 1 and 4 reporting having been diagnosed with a depressive disorder while 22.5-25.9% of residents in Ward 8 reporting having been diagnosed. These numbers are particularly striking considering that Ward 8 has the lowest access to primary care physicians who would make the diagnosis, and that even though White residents are slightly more likely to have been diagnosed with a depressive disorder than Black residents (19.4% vs. 18.7%, respectively), Ward 8, which is 92.8% Black, still had the highest rates of adults who were diagnosed with a depressive disorder (DC Department of Health, 2015). Figure 4 demonstrates diagnosis of a depressive disorder in adults by ward.

Depression diagnosis only tells a fraction of the story. Mental Health America also conducted a screening of depression in 2017 using phone interviews to survey a representative sample of participants from the 50 states and D.C. In addition to being asked whether they had been diagnosed with a depressive disorder, respondents were also given the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression screen which measures depressive symptoms. Respondents could then be categorized as having minimal, mild, moderate, moderately severe, or severe depression. Startlingly, 70% of respondents who had moderately severe and severe depression according to the screen reported never having been diagnosed by a medical professional (Mental Health America, 2017). This statistic demonstrates that the numbers obtained through looking solely at diagnosed cases are most likely a gross understatement of the true burden of mental illness.

Homelessness and Mental Health

Aside from the “State of Mental Health” and BRFSS data, little is known about per-state or -city mental health. However, there are proxies which can serve as indicators of mental health more generally. Homelessness is one such indicator.

Homelessness and poor mental health are closely tied. It is difficult to know what the general population’s mental health outcomes are because many people often go undiagnosed, but the population of people experiencing homelessness can sometimes serve as a proxy for the severest of cases since having a severe mental illness can make it difficult to keep a job and perform other functions necessary for keeping a home, thus leading many people with mental illness to eventually become homeless. By some estimates, between 30 and 50% of people experiencing homelessness have a severe mental illness, mainly psychoses, acute anxiety and personality disorders (Scott, 2018). Substance abuse comorbidities, such as alcohol or drug dependence, may be as high as 70% among the homeless (Salkow & Manfred, 2003). Homelessness then further exacerbates mental illness, as people are left feeling powerless and robbed of their dignity (Burn, 1992). This becomes a vicious cycle that keeps people on the streets instead of getting them treatment to break the cycle of homelessness.

One of Mayor Bowser’s priorities was to close down D.C. General, D.C.’s main homeless shelter, and replace it with smaller shelters, one in each ward. However, things did not go as planned and although D.C. General shut down, the new shelters were not opened in time, leaving many on the streets (Murphy & Tseu, 2018). Homelessness is not equally distributed across the wards of D.C. Unemployment, a risk factor for becoming homeless, is 17% in Ward 8 and 19% in Ward 7. In comparison, it is 4% in Ward 2 and 3.4% in Ward 3 (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Poverty, another factor which is closely correlated to homelessness, is similarly divided among wards. 35% of Ward 8 residents and 26% of Ward 7 residents live in poverty. In contrast, 6.9% of residents in Ward 3 and 9.9% of residents in Ward 4 live in poverty.

Figure 5a: Unemployment by ward (2005-2009). Source: Sustainable DC.

Figure 5b: Poverty prevalence by ward (2005-2009). Source: Sustainable DC.

During Mayor Gray’s administration, the Government of the District of Columbia Department of Mental Health Supportive Housing Strategic Plan 2012-2017 was created. This document outlines a plan to support people experiencing mental illness find housing that can provide what they need, instead of being put in an institution, and is currently undergoing revisions.

GAPS-friendly urban design in Washington DC

Green Spaces

As noted earlier, green space refers to “an area of grass, trees, or other vegetation set apart for recreational or aesthetic purposes in an otherwise urban environment” (Google, 2018). There are many areas of land which qualify as green space under this definition. National and local parks are the most obvious of these. Since they are open to the public and are part of government land (whether federal or district owned), this section will focus mostly on parks.

Local and National Parks

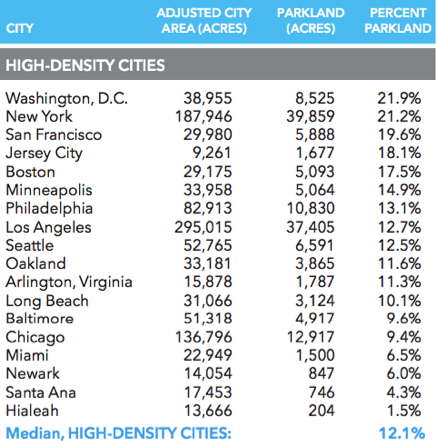

According to a 2017 report by the Trust for Public Land, Washington D.C. ranked #1 in the nation in terms of parkland percentage and parkland per 1,000 residents (The Trust for Public Land, 2017) (Figure 6). D.C. has 8,525 acres of parkland, accounting for 21.9% of its adjusted city area (which excludes airport and railroad acreage from total city land area). This translates to 12.9 acres of parkland for every 1,000 D.C. residents.

As noted earlier, green space refers to “an area of grass, trees, or other vegetation set apart for recreational or aesthetic purposes in an otherwise urban environment” (Google, 2018). There are many areas of land which qualify as green space under this definition. National and local parks are the most obvious of these. Since they are open to the public and are part of government land (whether federal or district owned), this section will focus mostly on parks.

Local and National Parks

According to a 2017 report by the Trust for Public Land, Washington D.C. ranked #1 in the nation in terms of parkland percentage and parkland per 1,000 residents (The Trust for Public Land, 2017) (Figure 6). D.C. has 8,525 acres of parkland, accounting for 21.9% of its adjusted city area (which excludes airport and railroad acreage from total city land area). This translates to 12.9 acres of parkland for every 1,000 D.C. residents.

Figure 6: Parkland as a percentage of adjusted city area and parkland per 1,000 residents by city. 2016 data. Source: The Trust for Public Land. (Parkland includes city, county, metro, state, and federal parkland within the city limits. Adjusted city area subtracts airport and railyard acreage from total city land area.)

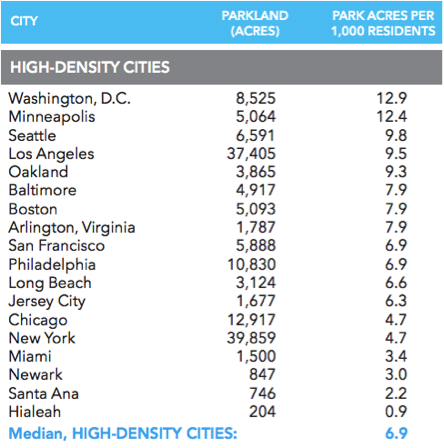

Local parks are areas of land set aside by the city to allow for the public to enjoy nature. They are designed to be handicap-accessible and are regularly maintained. Washington, D.C. has successfully implemented 23 community conservation and recreation projects since 1987, and currently D.C. is home to hundreds of local parks which are maintained by the city (NPS, 2017). These parks provide areas not only for District residents to enjoy nature and greenery, but they also promote physical activity and social interaction. Walking through the downtown area, it is easy to see that D.C. is a very green city. However, while local parks proliferate most of D.C., they are not evenly distributed. As seen in Figure 7, Ward 8 has abysmally few local parks as compared to the rest of the city. Certainly, not all residents of Ward 8 live within walking distance of a local park, and thus cannot benefit from the positive mental health outcomes of spending time in a park.

Figure 7: Local parks in D.C.. Source: D.C. Department of Parks and Recreation.

Aside from local parks, another source of public land with an abundance of green space is national parks. National parks are federally-owned lands which have been dedicated to conservation of the natural environment for the public to enjoy. The District has 25 national parks within its borders. It boasts 42,459,338 visitors to its national parks per year (NPS, 2017). If local parks are obviously unequally distributed, national parks are less so, perhaps because they are larger and thus more likely to span multiple wards. As seen in Figure 8, Wards 2, 3, 4 and 7 have the most acreage of national park space, and Ward 2 has the highest percentage of national park space. Ward 8 does not stand out as starkly as lacking park space when looking at national parks, as there are several parks which are included within Ward 8’s borders. However, as will be discussed in the next section, without adequate public transportation, walkability, or bikeability, it can be difficult to reach what few parks do exist in Ward 8.

Figure 8: National parks in and around Washington, D.C. Source: NPS.gov.

Contemporary Efforts to Expand Green Space

A keystone of Mayor Gray’s administration, being updated under Mayor Bowser’s administration, is Sustainability DC, an action plan for making D.C. the “healthiest, greenest, and most livable city in the nation” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). This document proposed many goals and targets for the year 2032. Included in the nature targets are to “cover 40% of the District with a healthy tree canopy” and “provide parkland or natural space within a 10-minute walk of all residents” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012).

Mayor Muriel Bowser’s administration was committed to continuing the efforts begun by Mayor Vincent Gray. In 2018, Mayor Bowser spearheaded the redesign of public space into what became Petworth Meditation Garden in Ward 4. The garden was designed to be available to all, with wheelchair-accessible pathways through the park, space for a community garden, drinking fountains for people and pets, bike racks, seating benches along the paths and central space, and a vegetated buffer. The project was community-led, with the goal of bringing people together (D.C. Office of the Mayor, 2018). This is just one example of the projects that Mayor Bowser initiated in order to facilitate community-building, especially in underserved areas of D.C.

A keystone of Mayor Gray’s administration, being updated under Mayor Bowser’s administration, is Sustainability DC, an action plan for making D.C. the “healthiest, greenest, and most livable city in the nation” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). This document proposed many goals and targets for the year 2032. Included in the nature targets are to “cover 40% of the District with a healthy tree canopy” and “provide parkland or natural space within a 10-minute walk of all residents” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012).

Mayor Muriel Bowser’s administration was committed to continuing the efforts begun by Mayor Vincent Gray. In 2018, Mayor Bowser spearheaded the redesign of public space into what became Petworth Meditation Garden in Ward 4. The garden was designed to be available to all, with wheelchair-accessible pathways through the park, space for a community garden, drinking fountains for people and pets, bike racks, seating benches along the paths and central space, and a vegetated buffer. The project was community-led, with the goal of bringing people together (D.C. Office of the Mayor, 2018). This is just one example of the projects that Mayor Bowser initiated in order to facilitate community-building, especially in underserved areas of D.C.

Active spaces

In the Sustainable DC Plan, Goal #1 of health and wellness is to “inspire healthy, active lifestyles for all residents regardless of income, ability, or employment” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). The Mayor’s Office plans to tackle this issue by increasing access and use of public parks and promoting healthy lifestyles through physical exercise.

Two ways that active spaces can be measured is through walkability and bikeability. These are measures of how easy it is to walk and bike from one place to another. For some people, going to a gym is a way to get physical activity. For many others, however, physical activity is built into the tasks of daily life, such as getting to and from work or school, and running errands. Thus, if these activities can be accomplished conveniently through walking or biking, people may end up incorporating greater physical activity simply by doing everyday activities, and thus reap the benefits of daily physical activity. A third measure which can correlate with increased daily physical activity is the availability of public transport, since using public transport often includes walking short distances to catch a bus or train, and then walking from the drop off spot to the actual destination.

In the Sustainable DC Plan, Goal #1 of health and wellness is to “inspire healthy, active lifestyles for all residents regardless of income, ability, or employment” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). The Mayor’s Office plans to tackle this issue by increasing access and use of public parks and promoting healthy lifestyles through physical exercise.

Two ways that active spaces can be measured is through walkability and bikeability. These are measures of how easy it is to walk and bike from one place to another. For some people, going to a gym is a way to get physical activity. For many others, however, physical activity is built into the tasks of daily life, such as getting to and from work or school, and running errands. Thus, if these activities can be accomplished conveniently through walking or biking, people may end up incorporating greater physical activity simply by doing everyday activities, and thus reap the benefits of daily physical activity. A third measure which can correlate with increased daily physical activity is the availability of public transport, since using public transport often includes walking short distances to catch a bus or train, and then walking from the drop off spot to the actual destination.

D.C. scored 67 out of 100 on bikeability, meaning that there is some bike infrastructure, but there are areas in which biking can be challenging or inconvenient. As with walkability and public transport, bikeability varies considerably by location within D.C. Currently, D.C. boasts 56 miles of bike lanes, most of which are concentrated in the center of D.C. In addition, it has 55 additional miles of trails, many of which lead out of the city and into the suburbs (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012).

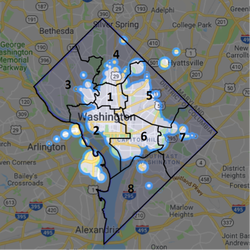

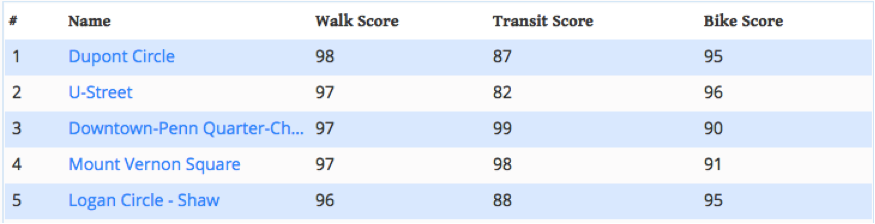

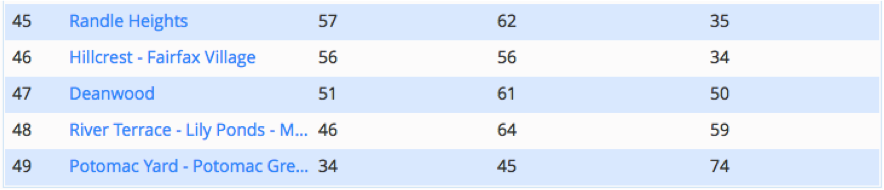

When broken down by neighborhood, D.C.’s walk, transit, and bike scores differ significantly. Figures 11a and 11b summarize the top five and bottom five neighborhoods in terms of aggregated walk, transit, and bike scores.

When broken down by neighborhood, D.C.’s walk, transit, and bike scores differ significantly. Figures 11a and 11b summarize the top five and bottom five neighborhoods in terms of aggregated walk, transit, and bike scores.

Figure 11a: Top 5 neighborhoods in D.C. for walkability, transit, and bikeability. Source: Walkscore.com

Figure 11b: Bottom 5 neighborhoods in D.C. for walkability, transit, and bikeability. Source: Walkscore.com

Among the top five neighborhoods for walkability, transit, and bikeability in Washington D.C., two (U-Street and Logan Circle) are in Ward 1 and three (Dupont Circle, Penn Quarter, and Mount Vernon Square) are in Ward 2, with Mount Vernon Square and Logan Circle also encompassing part of Ward 6. Among the bottom five neighborhoods, all but the Potomac Yard neighborhood are in Ward 7. The Potomac Yard neighborhood technically is not in D.C., but rather in Alexandria, Virginia, which is part of the metropolitan region of D.C.

Sustainability D.C. created several transportation targets, including increasing the use of public transit to 50% of all commuter trips, increasing biking and walking to 25% of all commuter trips, and reducing commuter trips made by car or taxi to 25% (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Whether it will be able to meet those targets remains to be seen. More importantly that meeting the aggregate targets, however, will be increasing access to active transportation options in the specific Wards in which currently there is very little.

Sustainability D.C. created several transportation targets, including increasing the use of public transit to 50% of all commuter trips, increasing biking and walking to 25% of all commuter trips, and reducing commuter trips made by car or taxi to 25% (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Whether it will be able to meet those targets remains to be seen. More importantly that meeting the aggregate targets, however, will be increasing access to active transportation options in the specific Wards in which currently there is very little.

Pro-social Spaces

As mentioned previously, the definition for pro-social spaces that will be used in this paper is places within the built environment where people can gather and interact, with a focus on the realm under the control of the city government. As the nation’s capital, Washington D.C. is known for its pro-social spaces, from museums to monuments, many of which are open to the public free of charge. However, as with so many other aspects of the GAPS framework, the distribution and type of pro-social places differs significantly across the city.

One of Washington D.C.’s proudest attractions is its network of seventeen Smithsonian museums, in addition to the National Zoological Park, all of which are free to the public (Smithsonian, 2018). These are excellent gathering spaces for social interaction. The Smithsonian institutions also regularly put on special interactive exhibits or educational events which are especially beneficial to families with children.

In addition to events put on by the Smithsonian institutions, free events regularly occur often in and around the National Mall (elongated grassy open park-type area) which promote social interaction. Protests and marches happen on the steps of the Supreme Court, in front of the White House, on the National Mall, and other locations with high visibility in the heart of the city. While sometimes portrayed as divisive, these gatherings provide the opportunity for people of similar identities to find others who share their passions.

In the literature on pro-social spaces in D.C., it is interesting to note that when referencing the city, many authors stick to what is available in the center, and do not make very much mention of the outskirts, especially not anywhere East of the Anacostia River. In a document published by the Office of the Mayor, the authors list several urban design elements which they argue promote social interaction and a feeling of cohesion for D.C.’s residents. They emphasize that these elements need to be applied to all parts of D.C., and not just the city’s center:

The District of Columbia has several programs which are targeted at under-served neighborhoods in D.C. and contribute to the development of pro-social places. One such project is the Healthy Corner Store Program, in which D.C. partners with local neighborhood shops to increase affordability and availability of fresh produce for people living in under-served neighborhoods (DC Central Kitchen, 2018). This program would not only decrease the food deserts in D.C.’s low-income communities, but it would promote the development of social capital as people would be encouraged to walk to and from the grocer, and thus meet and develop bonds with their neighbors and local businesses. Furthermore, it aligns with one of the Sustainable DC targets, which is to provide local food within half a mile of all residents of D.C. (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). As part of the goal is to source the produce locally, the Healthy Corner Store Program would encourage the use and expansion of community gardens in recreation centers and other government-owned properties in D.C.

The Anacostia Waterfront Initiative is another program which may benefit those in under-served communities and allow more people to access pro-social places. This project is focused on creating new parks, pedestrian crossings, and better transportation infrastructure along the Anacostia River (DC Office of the Mayor, 2018).

In Sustainability DC, one of the targets for the built environment is to “provide a variety of amenities and services within a 20-minute walk of all residents” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Within the target to provide a variety of amenities and services within walking distance is the action to “ease permitting requirements for temporary arts, community, and business uses.” This would allow for more opportunities to create temporary spaces of gathering, which would be instrumental in increasing social capital in the neighborhoods in which they take place. Another of the actions is to “convert five vacant buildings into permanent cultural or business incubation centers,” focusing on revamping buildings to the East of the Anacostia, in Wards 7 and 8. Business incubation centers provide the opportunity for small businesses to develop and grow. This initiative would take buildings which are currently unlivable and turn them into hubs of activity.

Another initiative which encourages pro-social placemaking is the “Live Near Your Work” grants. These were begun by the Office of Planning with the intent to incentivize people to live close to their workplaces so that they could walk to work. This would reduce car idling and traffic, and would encourage the development of social capital as people begin to recognize faces along their way to work. The grants are in the form of a subsidy which go to people who buy a house near where they work. This is especially important since walkable neighborhoods tend to be the least affordable to live in (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Of course being able to walk to work is ideal, and many people would live close to their work places if they could. The city would have to provide quite generous subsidies if it is to genuinely support low-income residents in their housing and work needs.

Restaurants and retail shops can be unexpected hubs of social activity within communities (Merlo, Bell, Menguc, & Whitwell, 2006). Humans have communed together since prehistory. Dining together is an important part of socializing in nearly every culture, and in communities where most of the shops are locally owned, it is part of the very fabric of the identity of the residents (Dunbar, 2007). Though this paper primarily focuses on the built environment that is under the control of the city, looking at the distribution of privately owned businesses, specifically restaurants, can help paint a picture of potential social gathering places.

In addition to the mental health benefits of being able to socialize with others in the community through dining together, there are other benefits of having restaurant choices. Living in a food desert has been linked to lower levels of social capital and perceived control (Dean, 2011). These factors directly link to poorer mental health, as people find comfort in feeling a sense of control about certain aspects of their lives, especially food, which is a basic need and is often deeply engrained in culture and identity.

Dining out need not be expensive, either. Typically, the more choices are available, the better natural competition can happen between restaurants to ensure that prices are kept low. It is important to note, however, that not everyone can afford to eat out, and that this itself can provide a barrier to the positive social capital gains that are linked to communal dining even if the community has many options. Thus, more efforts should be made by the city and federal government to provide subsidized communal dining experiences so that all may benefit from its capability to build social capital and improve mental health.

As seen in Figure 12, restaurant choices are significantly more limited in Wards 7 and 8, which may exacerbate the problem of affordability when there are fewer options from which to choose. Conversely, Wards 1 and 2 are saturated with options for dining out.

As mentioned previously, the definition for pro-social spaces that will be used in this paper is places within the built environment where people can gather and interact, with a focus on the realm under the control of the city government. As the nation’s capital, Washington D.C. is known for its pro-social spaces, from museums to monuments, many of which are open to the public free of charge. However, as with so many other aspects of the GAPS framework, the distribution and type of pro-social places differs significantly across the city.

One of Washington D.C.’s proudest attractions is its network of seventeen Smithsonian museums, in addition to the National Zoological Park, all of which are free to the public (Smithsonian, 2018). These are excellent gathering spaces for social interaction. The Smithsonian institutions also regularly put on special interactive exhibits or educational events which are especially beneficial to families with children.

In addition to events put on by the Smithsonian institutions, free events regularly occur often in and around the National Mall (elongated grassy open park-type area) which promote social interaction. Protests and marches happen on the steps of the Supreme Court, in front of the White House, on the National Mall, and other locations with high visibility in the heart of the city. While sometimes portrayed as divisive, these gatherings provide the opportunity for people of similar identities to find others who share their passions.

In the literature on pro-social spaces in D.C., it is interesting to note that when referencing the city, many authors stick to what is available in the center, and do not make very much mention of the outskirts, especially not anywhere East of the Anacostia River. In a document published by the Office of the Mayor, the authors list several urban design elements which they argue promote social interaction and a feeling of cohesion for D.C.’s residents. They emphasize that these elements need to be applied to all parts of D.C., and not just the city’s center:

- Strengthening civic identity through a renewed focus on assets such as public spaces, boulevards, and waterfront areas

- Designing for successful neighborhoods and large site reintegration

- Improving the public realm, particularly street and sidewalk space

- Addressing infrastructure and other barriers that affect aesthetic qualities

- Promoting design excellence throughout the city (DC Office of Planning, 2011).

The District of Columbia has several programs which are targeted at under-served neighborhoods in D.C. and contribute to the development of pro-social places. One such project is the Healthy Corner Store Program, in which D.C. partners with local neighborhood shops to increase affordability and availability of fresh produce for people living in under-served neighborhoods (DC Central Kitchen, 2018). This program would not only decrease the food deserts in D.C.’s low-income communities, but it would promote the development of social capital as people would be encouraged to walk to and from the grocer, and thus meet and develop bonds with their neighbors and local businesses. Furthermore, it aligns with one of the Sustainable DC targets, which is to provide local food within half a mile of all residents of D.C. (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). As part of the goal is to source the produce locally, the Healthy Corner Store Program would encourage the use and expansion of community gardens in recreation centers and other government-owned properties in D.C.

The Anacostia Waterfront Initiative is another program which may benefit those in under-served communities and allow more people to access pro-social places. This project is focused on creating new parks, pedestrian crossings, and better transportation infrastructure along the Anacostia River (DC Office of the Mayor, 2018).

In Sustainability DC, one of the targets for the built environment is to “provide a variety of amenities and services within a 20-minute walk of all residents” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Within the target to provide a variety of amenities and services within walking distance is the action to “ease permitting requirements for temporary arts, community, and business uses.” This would allow for more opportunities to create temporary spaces of gathering, which would be instrumental in increasing social capital in the neighborhoods in which they take place. Another of the actions is to “convert five vacant buildings into permanent cultural or business incubation centers,” focusing on revamping buildings to the East of the Anacostia, in Wards 7 and 8. Business incubation centers provide the opportunity for small businesses to develop and grow. This initiative would take buildings which are currently unlivable and turn them into hubs of activity.

Another initiative which encourages pro-social placemaking is the “Live Near Your Work” grants. These were begun by the Office of Planning with the intent to incentivize people to live close to their workplaces so that they could walk to work. This would reduce car idling and traffic, and would encourage the development of social capital as people begin to recognize faces along their way to work. The grants are in the form of a subsidy which go to people who buy a house near where they work. This is especially important since walkable neighborhoods tend to be the least affordable to live in (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Of course being able to walk to work is ideal, and many people would live close to their work places if they could. The city would have to provide quite generous subsidies if it is to genuinely support low-income residents in their housing and work needs.

Restaurants and retail shops can be unexpected hubs of social activity within communities (Merlo, Bell, Menguc, & Whitwell, 2006). Humans have communed together since prehistory. Dining together is an important part of socializing in nearly every culture, and in communities where most of the shops are locally owned, it is part of the very fabric of the identity of the residents (Dunbar, 2007). Though this paper primarily focuses on the built environment that is under the control of the city, looking at the distribution of privately owned businesses, specifically restaurants, can help paint a picture of potential social gathering places.

In addition to the mental health benefits of being able to socialize with others in the community through dining together, there are other benefits of having restaurant choices. Living in a food desert has been linked to lower levels of social capital and perceived control (Dean, 2011). These factors directly link to poorer mental health, as people find comfort in feeling a sense of control about certain aspects of their lives, especially food, which is a basic need and is often deeply engrained in culture and identity.

Dining out need not be expensive, either. Typically, the more choices are available, the better natural competition can happen between restaurants to ensure that prices are kept low. It is important to note, however, that not everyone can afford to eat out, and that this itself can provide a barrier to the positive social capital gains that are linked to communal dining even if the community has many options. Thus, more efforts should be made by the city and federal government to provide subsidized communal dining experiences so that all may benefit from its capability to build social capital and improve mental health.

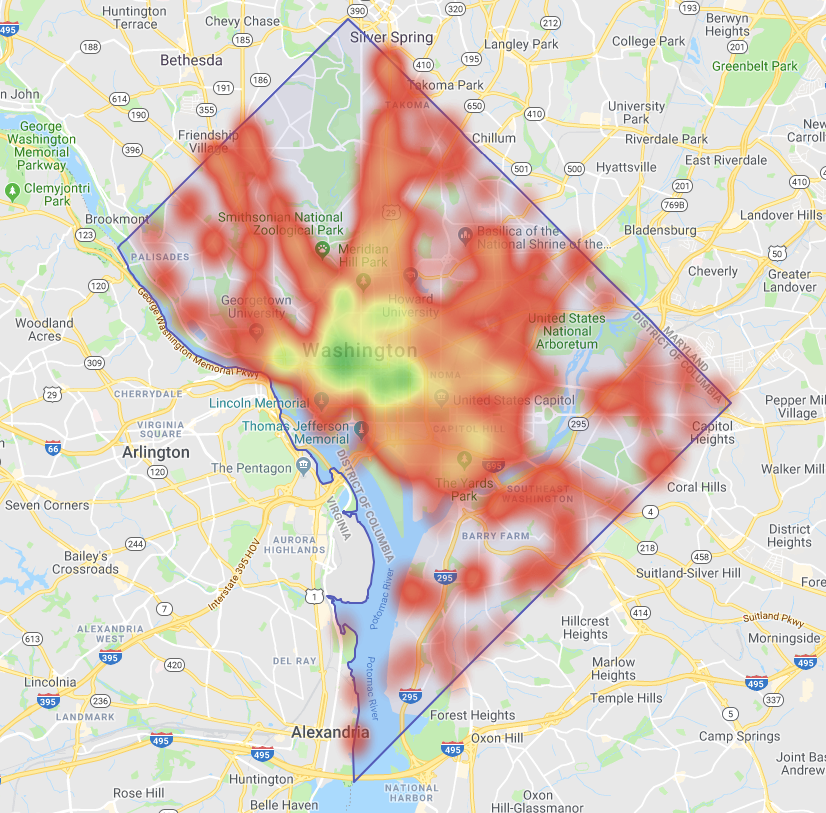

As seen in Figure 12, restaurant choices are significantly more limited in Wards 7 and 8, which may exacerbate the problem of affordability when there are fewer options from which to choose. Conversely, Wards 1 and 2 are saturated with options for dining out.

Figure 12: Concentration of restaurant choices in Washington, D.C. Source: WalkScore.com

Safe Spaces

The Mayor’s Office understands the importance of urban design in promoting safety. As part of its Sustainability D.C. plan, it states, “we envision a District where…our neighborhoods will provide safe, comfortable homes and access to essential services so all residents can lead healthy and prosperous lives” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). While parts of D.C. are fairly safe, there are pockets of D.C. in which violent crime is still quite high. Overall, residents in D.C. have a 1 in 83 chance of being a victim of a violent crime over their lifetimes (Location Inc, 2017). By comparison, residents in Chicago have a 1 in 90 chance of being a victim, and in Philadelphia, they have a 1 in 101 chance.

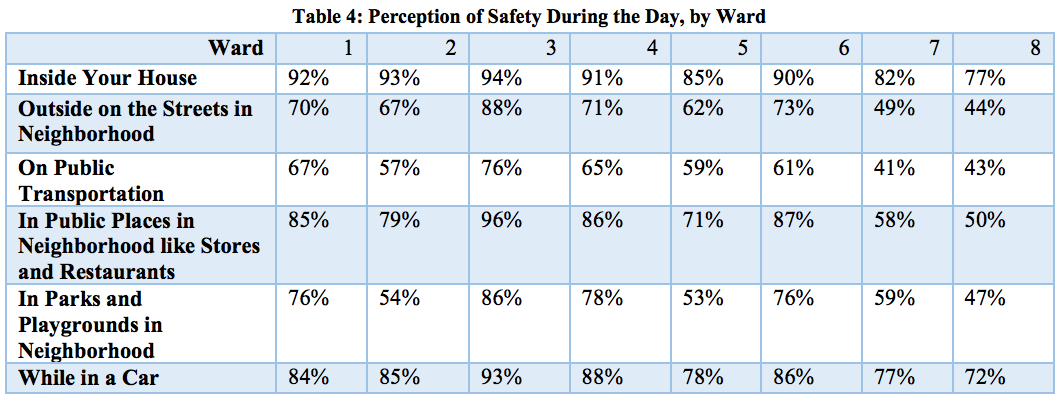

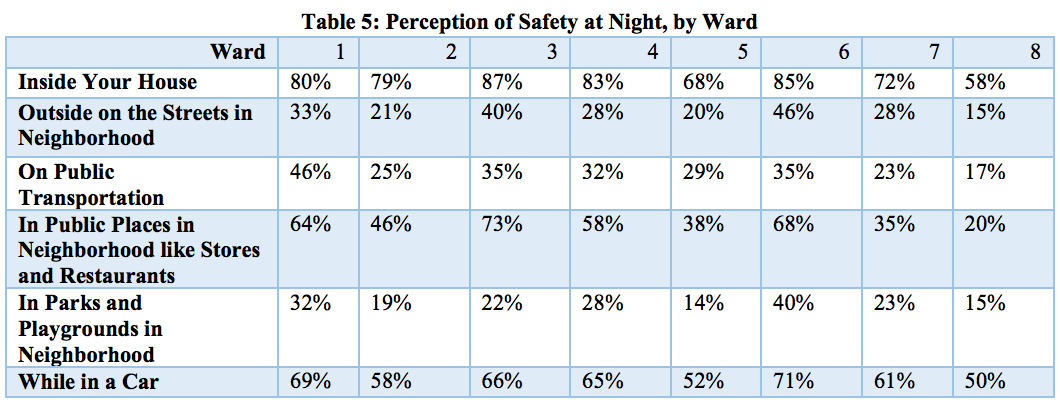

Depending on where they live, D.C.’s residents feel differing levels of safety in their communities. According to a 2015 survey, residents living in wards 2, 5, 7 and 8 were significantly less likely to feel safe in their neighborhoods during the day than residents of wards 1, 3, 4 and 6 (Community Preservation and Development Corporation, 2016). Out of all the wards, residents living in Ward 8 felt the least safe in their neighborhoods, followed closely by Ward 7. Figures 13a and 13b demonstrate the stark contrast in perceptions of safety between residents to the East of the Anacostia River (Wards 7 and 8) and residents to the West (all other wards). Fewer than half of the residents of Wards 7 and 8 feel safe during the day on their streets and on public transportation, while in the other wards, perceptions of safety on the streets and on public transportation are above 60%. Strikingly, only 44% of respondents from Ward 8 felt safe outside on the streets in their neighborhood during the day, and this number dropped to 15% at night.

The Mayor’s Office understands the importance of urban design in promoting safety. As part of its Sustainability D.C. plan, it states, “we envision a District where…our neighborhoods will provide safe, comfortable homes and access to essential services so all residents can lead healthy and prosperous lives” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). While parts of D.C. are fairly safe, there are pockets of D.C. in which violent crime is still quite high. Overall, residents in D.C. have a 1 in 83 chance of being a victim of a violent crime over their lifetimes (Location Inc, 2017). By comparison, residents in Chicago have a 1 in 90 chance of being a victim, and in Philadelphia, they have a 1 in 101 chance.

Depending on where they live, D.C.’s residents feel differing levels of safety in their communities. According to a 2015 survey, residents living in wards 2, 5, 7 and 8 were significantly less likely to feel safe in their neighborhoods during the day than residents of wards 1, 3, 4 and 6 (Community Preservation and Development Corporation, 2016). Out of all the wards, residents living in Ward 8 felt the least safe in their neighborhoods, followed closely by Ward 7. Figures 13a and 13b demonstrate the stark contrast in perceptions of safety between residents to the East of the Anacostia River (Wards 7 and 8) and residents to the West (all other wards). Fewer than half of the residents of Wards 7 and 8 feel safe during the day on their streets and on public transportation, while in the other wards, perceptions of safety on the streets and on public transportation are above 60%. Strikingly, only 44% of respondents from Ward 8 felt safe outside on the streets in their neighborhood during the day, and this number dropped to 15% at night.

Figure 13a: Perceptions of safety during the day, by ward. Source: Community Preservation and Development Corporation, 2016.

Figure 13b: Perceptions of safety at night, by ward. Source: Community Preservation and Development Corporation, 2016.

These numbers paint a deeply troubling picture. Not only do residents of Wards 7 and 8 have fewer GAPS-friendly design elements than the other wards, but in addition, the residents do not feel safe in those spaces. If people do not feel safe in parks, buses, or restaurants, or even their own neighborhood streets, then they will be disincentivized to spend time in these places. In fact, the only places in which 50% or more of residents in Wards 7 and 8 feel safe at night is their homes and cars. These are the two places in which people receive very little contact with greenery, are not required to be active, and do not necessarily promote social behaviors. Thus, for the more than 50% of the population that feels unsafe in the parks, neighborhood streets, restaurants, and other social, active, green spaces, the presence of these components does not help them receive any of the mental health benefits since they are disincentivized to use them. This is essential for key decision-makers who want to implement mental health-friendly design to understand. The GAPS components must all be present and work in unison for the full positive mental health effects to take place.

There are several initiatives by the city to improve the safety of D.C. residents through urban design. For example, a report released by the Community Preservation and Development Corporation listed seven recommendations for improving public safety and community-police relations. Recommendation number 4 directly addresses the role of the built environment in improving safety: “Environmental approaches to improving public safety should be more fully incorporated into public safety plans” (Community Preservation and Development Corporation, 2016). These include improving lighting in parks and on streets and setting up cameras in strategic locations to deter crime. Another example comes from one of the goals outlined in Sustainable DC, which aims to “create safe environments that are conducive to healthy living” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Embedded in that is to “develop a ‘healthy by design’ program for new affordable housing projects, with priority focus in low-income and underserved neighborhoods.” Hopefully, these initiatives will increase the real and perceived safety of residents East of the Anacostia River so that people can utilize the green, active, and pro-social spaces in their communities.

Schools as Safe Places

Children in D.C. spend an average of 7 hours a day, 181 days a year in school (NCES, 2008). Given that they spend much of their lives in school buildings, many resources should be allotted to keeping children safe in school and school-related activities. Surprisingly, there are not many publicly available documents that analyze school safety from an urban design perspective. Rather, the focus has been on hiring sufficient safety personnel to protect the students.

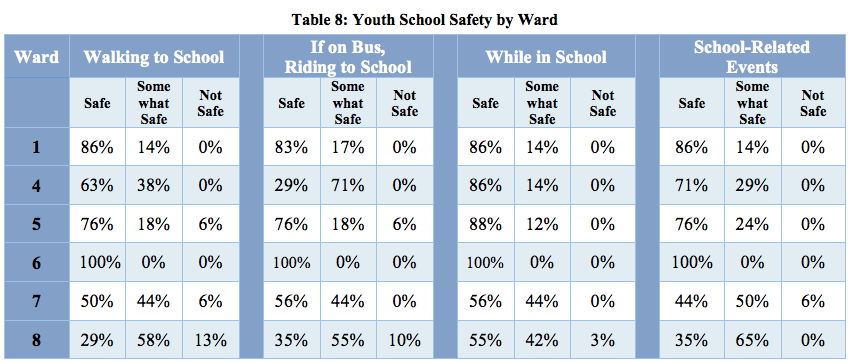

The issue of safety in schools is, not surprisingly, also divided along the Anacostia River. As seen in Figure 14, only 35% of children in Ward 8 feel safe riding a bus to school, and only 29% feel safe walking to school. In every ward except Ward 8, fewer than 7% of students reported feeling “not safe” walking or riding the bus to school, while in Ward 8, 10% or more reported feeling “not safe.”

There are several initiatives by the city to improve the safety of D.C. residents through urban design. For example, a report released by the Community Preservation and Development Corporation listed seven recommendations for improving public safety and community-police relations. Recommendation number 4 directly addresses the role of the built environment in improving safety: “Environmental approaches to improving public safety should be more fully incorporated into public safety plans” (Community Preservation and Development Corporation, 2016). These include improving lighting in parks and on streets and setting up cameras in strategic locations to deter crime. Another example comes from one of the goals outlined in Sustainable DC, which aims to “create safe environments that are conducive to healthy living” (Office of Planning and Department of Energy & Environment, 2012). Embedded in that is to “develop a ‘healthy by design’ program for new affordable housing projects, with priority focus in low-income and underserved neighborhoods.” Hopefully, these initiatives will increase the real and perceived safety of residents East of the Anacostia River so that people can utilize the green, active, and pro-social spaces in their communities.

Schools as Safe Places

Children in D.C. spend an average of 7 hours a day, 181 days a year in school (NCES, 2008). Given that they spend much of their lives in school buildings, many resources should be allotted to keeping children safe in school and school-related activities. Surprisingly, there are not many publicly available documents that analyze school safety from an urban design perspective. Rather, the focus has been on hiring sufficient safety personnel to protect the students.

The issue of safety in schools is, not surprisingly, also divided along the Anacostia River. As seen in Figure 14, only 35% of children in Ward 8 feel safe riding a bus to school, and only 29% feel safe walking to school. In every ward except Ward 8, fewer than 7% of students reported feeling “not safe” walking or riding the bus to school, while in Ward 8, 10% or more reported feeling “not safe.”

Figure 14: Youth school safety by ward. Source: Community Preservation and Development Corporation, 2016.

Notably, Ward 8 was the only ward in which any students reported feeling “not safe” while in school. Even in Ward 8, only 3% reported feeling unsafe while in school. Perhaps these low numbers are because there have not been any major school shootings in recent years in D.C. What is common, however, is shootings that occur near schools.

There is an issue with children safely getting to and from school. D.C. has 120 charter schools, and getting to school for the 46% of students who go to charter schools means taking the metro or other form of public transportation (DC Public Charter School Board, 2018). In order to ensure that students are safe on their commutes to and from school, some communities have begun “Man the Block” initiatives, in which volunteers are stationed at strategic locations to help students have safe passage to and from school (Stein, 2016). These initiatives have shown to be helpful in increasing perceptions of safety among students and may help to reduce the percentage of students who feel unsafe on their commutes to school in Ward 8 (Stein, 2016).

Recreation centers can often provide a sanctuary from violence, especially for children and teenagers. For children whose parents or caretakers work during the day, recreation centers are a safer alternative than the streets to spend time after school. Recreation centers come with the added bonus of providing productive activities such as sports and art classes. The Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) defines its recreation centers as “safe zones for children and teens [which] offer families an opportunity to enjoy special activities and events close to home” (DC Office of the Mayor, 2018). Since recreation centers are enclosed and are maintained by the city, they are unique places within the built environment in which creating a feeling of safety can be achieved regardless of the conditions of the surrounding community. Fortunately, as seen in Figure 15, recreation centers are prevalent in all eight wards, with no D.C. resident living further than two miles from a recreation center (DC Office of the Mayor, 2018).

There is an issue with children safely getting to and from school. D.C. has 120 charter schools, and getting to school for the 46% of students who go to charter schools means taking the metro or other form of public transportation (DC Public Charter School Board, 2018). In order to ensure that students are safe on their commutes to and from school, some communities have begun “Man the Block” initiatives, in which volunteers are stationed at strategic locations to help students have safe passage to and from school (Stein, 2016). These initiatives have shown to be helpful in increasing perceptions of safety among students and may help to reduce the percentage of students who feel unsafe on their commutes to school in Ward 8 (Stein, 2016).