Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2020:6;12 (Advance publication 2019)

|

CITY CASE STUDY

|

Urban design and mental health in Toronto, Canada: a city case study

Kyle Lee (1, 2), Falen Fernandes (3), Marissa Ng (4), Violetta-Evelyn Reznikov (5), Michael Poos (6)

(1) Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, ON

(2) St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON

(3) University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

(4) McKinsey & Company, Toronto, ON

(5) Ryerson University, Toronto, ON

(6) Ministry of Municipal Affairs, Toronto, ON

(1) Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, ON

(2) St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON

(3) University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

(4) McKinsey & Company, Toronto, ON

(5) Ryerson University, Toronto, ON

(6) Ministry of Municipal Affairs, Toronto, ON

The authors would like to begin by acknowledging that the land on which our study is based is the traditional territory of the Wendat, the Anishnaabeg, Haudenosaunee, Métis, and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation. We are grateful for the opportunity to work on this land.

Introduction

Toronto, situated in the province of Ontario, is the largest city in Canada and one of the largest cities in North America. As the world population grows increasingly urbanized, life in the city remains challenging as its inhabitants face unique obstacles. Such obstacles may impact on an individual’s mental health. Fortunately in Toronto, 7 in 10 people rate their mental health as 'excellent' or 'very good' (Canadian Community Health Survey (2014). However, several key themes including immigration, stigma, access to services, and poverty and affordability affect mental health outcomes. In this case report, we will provide a general overview of mental health and planning in Toronto and examine four key themes of urban design and its effect on mental health and well-being of Torontonians.

Figure 1. Views of Toronto skyline as seen from Toronto Islands. By Kyle Lee, 2018. Reprinted with permission.

Methods

Literature review

A search was conducted in 2018 to identify mental health, policy, urban planning and other related data most relevant to Toronto. This information was analyzed and assessed for relevance to urban design and mental health in Toronto. Significant policies and examples of development suggested by interviewees were also included in the final report.

Interviews

A total of twelve Toronto-based academics, public health specialists, mental health specialists, urban planners, designers, and developers were identified using snowball sampling. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with each person based on a predetermined interview proforma. Each interviewee was asked for consent before proceeding, and verbally consented to recording of the interview. Interviewees were asked about components of urban design that improved mental health, if they thought there was an intent to prioritize mental health in urban planning and design, known guidelines and policies currently in place, examples of local developments or designs and barriers and other questions suggested by the Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health protocol.

A search was conducted in 2018 to identify mental health, policy, urban planning and other related data most relevant to Toronto. This information was analyzed and assessed for relevance to urban design and mental health in Toronto. Significant policies and examples of development suggested by interviewees were also included in the final report.

Interviews

A total of twelve Toronto-based academics, public health specialists, mental health specialists, urban planners, designers, and developers were identified using snowball sampling. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with each person based on a predetermined interview proforma. Each interviewee was asked for consent before proceeding, and verbally consented to recording of the interview. Interviewees were asked about components of urban design that improved mental health, if they thought there was an intent to prioritize mental health in urban planning and design, known guidelines and policies currently in place, examples of local developments or designs and barriers and other questions suggested by the Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health protocol.

Overview of Mental Health in Toronto

Immigration

Immigration and diversity play a significant role in Toronto. Toronto alone receives an average of 50,000 newcomers annually (Statistics Canada, 2016). Almost half of Toronto residents were born outside Canada (Statistics Canada, 2016). These figures demonstrate the significance of immigration to Canada’s economy and sociocultural diversity (Srirangson et al, 2013). However, many new immigrants face barriers and challenges integrating into a new society and culture, as well as racism and discrimination that may affect mental health.

“Toronto proper is adding 2-5% depending on its population. The question now becomes, how do you handle immigration?” - Researcher

Stigma

Stigma around mental illness continues to exist:

“Most still conflate the concept of mental health as meaning mental illness. As a result, there has been a stigma attached to addressing mental health in design. At the same time, without a proper understanding of mental health as a positive concept, there has been a lack of focus on how city design can promote health.” – Public health consultant.

Fortunately, over half of Canadians surveyed believe that mental illness stigma has diminished compared to 5 years ago (Bell Canada, 2015). In recent years, influential organizations such as the Toronto District School Board have focused their efforts in anti-stigma initiatives as part of Ontario government’s Children and Youth Mental Health & Well-being Strategy (Toronto District School Board, 2013). In addition to using traditional means such as education and community programs, healthy urban design may also play an important role in reducing mental health stigma.

Access

Access to mental health services remains a barrier to most Torontonians. 75% of children with mental illness cannot access specialized treatment services (Waddell et al, 2015). Wait times for counselling and therapy can often be up to one year for children and youth (Children’s Mental Health Ontario, 2016; Office of the Auditor General of Ontario, 2016). Funding is short by $1.5 billion based on the proportion of mental illness of the population (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2014; Brien et al, 2015).

Although Canada has a single payer universal healthcare system, certain mental health services are not funded by the government. For example, counselling and therapy done with a non-physician is an out-of-pocket expense. Primary care providers like doctors and nurse practitioners provide government-funded diagnosis and treatments. However, specialized psychiatry support may be limited. Access to psychiatrists across the Greater Toronto Area varies, ranging from 4.7 psychiatrists per 100,000 people in Central West LHIN region to 62.7 psychiatrists per 100,000 people in Toronto Central LHIN (Kurdyak et al, 2014).

Fortunately, a recent $100 million anonymous donation to Centre for Addiction and Mental Health foundation, part of the largest mental health facility in Toronto, will lead to increased investment in mental health research and treatment (Picard, 2018). Furthermore, addition of innovative but somewhat controversial overdose prevention sites have emerged in various parts of Toronto:

“These [overdose prevention sites] are examples of informal ‘city planners’ who are taking initiative to design projects in the build environment that improve mental health when faced with barriers at the governmental level” - Public health consultant.

However, mental health funding remains a key concern for health care providers and patients in Toronto.

Poverty and Affordability

Toronto’s growth in population and urban development have also led to an affordability crisis.

“If the city keeps growing, there is nowhere for anybody to live, so how is everybody going to get around?” - Public health specialist.

Large portions of the city now exhibit social risk factors of city-living, particularly challenging when segregation based on minorities have been shown to be a risk factor for poor mental health in cities (Gruebner et al, 2017). Between 1970 and 2005 Toronto has become more and more segregated geographically defined along socio-economic lines (Hulchanski, 2007). Most strikingly, middle-income communities have begun to disappear. Poverty has been associated with poor mental health outcomes and recent trends show that this is a worsening issue for Toronto (Hulchanski, 2007).

Immigration and diversity play a significant role in Toronto. Toronto alone receives an average of 50,000 newcomers annually (Statistics Canada, 2016). Almost half of Toronto residents were born outside Canada (Statistics Canada, 2016). These figures demonstrate the significance of immigration to Canada’s economy and sociocultural diversity (Srirangson et al, 2013). However, many new immigrants face barriers and challenges integrating into a new society and culture, as well as racism and discrimination that may affect mental health.

“Toronto proper is adding 2-5% depending on its population. The question now becomes, how do you handle immigration?” - Researcher

Stigma

Stigma around mental illness continues to exist:

“Most still conflate the concept of mental health as meaning mental illness. As a result, there has been a stigma attached to addressing mental health in design. At the same time, without a proper understanding of mental health as a positive concept, there has been a lack of focus on how city design can promote health.” – Public health consultant.

Fortunately, over half of Canadians surveyed believe that mental illness stigma has diminished compared to 5 years ago (Bell Canada, 2015). In recent years, influential organizations such as the Toronto District School Board have focused their efforts in anti-stigma initiatives as part of Ontario government’s Children and Youth Mental Health & Well-being Strategy (Toronto District School Board, 2013). In addition to using traditional means such as education and community programs, healthy urban design may also play an important role in reducing mental health stigma.

Access

Access to mental health services remains a barrier to most Torontonians. 75% of children with mental illness cannot access specialized treatment services (Waddell et al, 2015). Wait times for counselling and therapy can often be up to one year for children and youth (Children’s Mental Health Ontario, 2016; Office of the Auditor General of Ontario, 2016). Funding is short by $1.5 billion based on the proportion of mental illness of the population (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2014; Brien et al, 2015).

Although Canada has a single payer universal healthcare system, certain mental health services are not funded by the government. For example, counselling and therapy done with a non-physician is an out-of-pocket expense. Primary care providers like doctors and nurse practitioners provide government-funded diagnosis and treatments. However, specialized psychiatry support may be limited. Access to psychiatrists across the Greater Toronto Area varies, ranging from 4.7 psychiatrists per 100,000 people in Central West LHIN region to 62.7 psychiatrists per 100,000 people in Toronto Central LHIN (Kurdyak et al, 2014).

Fortunately, a recent $100 million anonymous donation to Centre for Addiction and Mental Health foundation, part of the largest mental health facility in Toronto, will lead to increased investment in mental health research and treatment (Picard, 2018). Furthermore, addition of innovative but somewhat controversial overdose prevention sites have emerged in various parts of Toronto:

“These [overdose prevention sites] are examples of informal ‘city planners’ who are taking initiative to design projects in the build environment that improve mental health when faced with barriers at the governmental level” - Public health consultant.

However, mental health funding remains a key concern for health care providers and patients in Toronto.

Poverty and Affordability

Toronto’s growth in population and urban development have also led to an affordability crisis.

“If the city keeps growing, there is nowhere for anybody to live, so how is everybody going to get around?” - Public health specialist.

Large portions of the city now exhibit social risk factors of city-living, particularly challenging when segregation based on minorities have been shown to be a risk factor for poor mental health in cities (Gruebner et al, 2017). Between 1970 and 2005 Toronto has become more and more segregated geographically defined along socio-economic lines (Hulchanski, 2007). Most strikingly, middle-income communities have begun to disappear. Poverty has been associated with poor mental health outcomes and recent trends show that this is a worsening issue for Toronto (Hulchanski, 2007).

Overview of planning in Toronto

The City of Toronto is the largest metropolitan with a population of 2,731,571 according to the 2016 Canadian census. Toronto is at the centre, however, of a much larger city-region, often referred to as the Greater Golden Horseshoe (or Greater Toronto and Hamilton Region). This large urban conurbation stretches from the Canada-US border in Niagara Falls and wraps around the shores of Lake Ontario in a pattern that resembles a “horseshoe”. This greater region encompasses a population of almost 9.4 million, which is over one-quarter of the population of the entire country (Statistics Canada, 2016).

The municipal government is made up of the formally independent, or partially-independent, municipalities of Toronto, Etobicoke, Scarborough, York, North York, East York, Mimico, Long Branch, New Toronto, Swansea, Weston, Forest Hill and Leaside. These former municipalities at various times represented newly-formed suburbs for the growing old city of Toronto. As a result, the built form and urban fabric of these communities vary significantly from the older, central neighbourhoods in the old city of Toronto. Overall, the general land use pattern and urban form of present day Toronto is the resulting waves of ‘suburbanization’ (Solomon, 2007). Indeed, Toronto had very little planning at all prior to the 1940s (White, 2016). Paradoxically, these “unplanned” portions of old city Toronto now make up some of the most desirable, transit-rich, and walkable neighbourhoods of the region today and compare favourably to the less-walkable nature of auto-oriented suburban development that followed from the emergence of planning in Toronto.

Founded as Fort York in 1783, Toronto grew organically along a rough grid-like pattern first surveyed by British military leadership after the American Revolution. This grid of 1.25 mile squares eventually spread north and along the west-east orientation of Lake Ontario as a way to facilitate the creation of farms (Solomon, 2007). These patterns exist to this day, with the original gridlines now making up the region’s multi-lane arterial roads. As the city grew from a provincial town to an industrial city, factories and railways were built close to the shores of Lake Ontario for easier access to shipping. Torontonians often lament the loss of connectivity to the lakefront such industrial infrastructure imposed on the city, a problem made worse with the addition of a large elevated highway, the Gardiner Expressway, in 1958.

Before the 1940s, the industrial working populations grew along streets served by streetcars (or “trolleys”). Before the automobile, streetcars were the primary mode of transportation both within and across municipalities. Serving the growing network of streetcar routes were residential neighbourhoods with houses on densely packed, narrow lots. These neighbourhoods were located within easy walking distance in behind the commercial main streets that evolved along the streetcar lines. This pattern of urbanization continued until the first formal “plan” for Toronto emerged in the early 1940s.

The Toronto Metropolitan Area Master Plan 1943 outlined a series of “superhighways” serving and connecting smaller, disparate residential country towns. In 1953, the Province created Metro Toronto, a two-tiered municipal governance structure including the original City of Toronto along with five neighbouring Townships (Etobicoke, York, North York, East York, and Scarborough) and a number of smaller Villages (Long Branch, New Toronto, Mimico, Swansea, Weston, Forest Hill, and Leaside). Created by the Provincial government as a way to share the cost of infrastructure for the growing city-region, Metro Toronto was responsible for coordinating infrastructure planning and expansion across all the former municipalities, while the lower-tier municipalities retained control over local development. The result in practice was a financing arrangement whereby the older, tax-rich City of Toronto subsidized the expansion of infrastructure of the surrounding suburbs (Solomon, 2007).

Richard White, in his book Planning Toronto: the Planners, the Plans, Their Legacies, 1940-1980, describes how planning truly began in Toronto with a flurry of plans at the local, Metro Toronto, and Provincial level between the mid-1950s until about 1970. This period represents Toronto’s modernist era, where theoretical ideas such as le Corbusier’s “Towers in a Park” came to life and intersected with planners attempting to impose rationality and “functionalism” to the design of the city and its streets (White, 2016). This intersection resulted in the development of Toronto’s second most identifiable urban form: clusters of ‘slab’ apartment buildings surrounded by open spaces and large amount of surface and underground parking. Large infrastructure projects define this period; from the overhaul of water and wastewater systems to the creation of multi-lane, free-flowing highways

Citizen-led opposition to many of these large-scale projects signaled the end of Toronto’s modernist planning period. Most famously, the American author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs, helped mobilize opposition to the “Spadina Expressway”, which would have run along Spadina Avenue, a broad, prominent avenue that connects many of Toronto’s most beloved neighbourhoods. Shown on plans since the 1943 Metropolitan Area Master Plan, the Province of Ontario cancelled the construction project in 1971. Pressure from local residents garnered political support and the planners of Metro Toronto found themselves becoming more and more impeded in their attempts to build large scale infrastructure on the municipality. If the modernist planning period in Toronto had been typified by deference to expertise, then the time from the early 1970s onward was characterized more by experts looking to citizens for approval (White, 2016). A re-centring of the local over the metropolitan saw planning become more about community engagement. Efforts at urban renewal were slowed and existing low-rise neighbourhoods became impervious to change with each successive Official Plan.

The mid-2000s saw the Province of Ontario release two landmark plans of regional importance: The Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe and the Big Move. They represented a major shift in planning policy for a region that had been sprawling for decades. The Growth Plan designated nodes of density at key locations (designated “urban growth centres”) served by high-order local and regional transit whose future priorities were set out in the Big Move. Municipalities have embraced the challenge, with planning now focused on creating complete communities that are focused on a mixture of uses, mid-rise built forms breaking the monotony of single-family homes or clusters of slab apartment buildings. Mid-rise buildings are particularly encouraged for mixed-use areas the current Toronto Official Plan calls Avenues, many of which are still served by those pre-automotive streetcars lines.

The municipal government is made up of the formally independent, or partially-independent, municipalities of Toronto, Etobicoke, Scarborough, York, North York, East York, Mimico, Long Branch, New Toronto, Swansea, Weston, Forest Hill and Leaside. These former municipalities at various times represented newly-formed suburbs for the growing old city of Toronto. As a result, the built form and urban fabric of these communities vary significantly from the older, central neighbourhoods in the old city of Toronto. Overall, the general land use pattern and urban form of present day Toronto is the resulting waves of ‘suburbanization’ (Solomon, 2007). Indeed, Toronto had very little planning at all prior to the 1940s (White, 2016). Paradoxically, these “unplanned” portions of old city Toronto now make up some of the most desirable, transit-rich, and walkable neighbourhoods of the region today and compare favourably to the less-walkable nature of auto-oriented suburban development that followed from the emergence of planning in Toronto.

Founded as Fort York in 1783, Toronto grew organically along a rough grid-like pattern first surveyed by British military leadership after the American Revolution. This grid of 1.25 mile squares eventually spread north and along the west-east orientation of Lake Ontario as a way to facilitate the creation of farms (Solomon, 2007). These patterns exist to this day, with the original gridlines now making up the region’s multi-lane arterial roads. As the city grew from a provincial town to an industrial city, factories and railways were built close to the shores of Lake Ontario for easier access to shipping. Torontonians often lament the loss of connectivity to the lakefront such industrial infrastructure imposed on the city, a problem made worse with the addition of a large elevated highway, the Gardiner Expressway, in 1958.

Before the 1940s, the industrial working populations grew along streets served by streetcars (or “trolleys”). Before the automobile, streetcars were the primary mode of transportation both within and across municipalities. Serving the growing network of streetcar routes were residential neighbourhoods with houses on densely packed, narrow lots. These neighbourhoods were located within easy walking distance in behind the commercial main streets that evolved along the streetcar lines. This pattern of urbanization continued until the first formal “plan” for Toronto emerged in the early 1940s.

The Toronto Metropolitan Area Master Plan 1943 outlined a series of “superhighways” serving and connecting smaller, disparate residential country towns. In 1953, the Province created Metro Toronto, a two-tiered municipal governance structure including the original City of Toronto along with five neighbouring Townships (Etobicoke, York, North York, East York, and Scarborough) and a number of smaller Villages (Long Branch, New Toronto, Mimico, Swansea, Weston, Forest Hill, and Leaside). Created by the Provincial government as a way to share the cost of infrastructure for the growing city-region, Metro Toronto was responsible for coordinating infrastructure planning and expansion across all the former municipalities, while the lower-tier municipalities retained control over local development. The result in practice was a financing arrangement whereby the older, tax-rich City of Toronto subsidized the expansion of infrastructure of the surrounding suburbs (Solomon, 2007).

Richard White, in his book Planning Toronto: the Planners, the Plans, Their Legacies, 1940-1980, describes how planning truly began in Toronto with a flurry of plans at the local, Metro Toronto, and Provincial level between the mid-1950s until about 1970. This period represents Toronto’s modernist era, where theoretical ideas such as le Corbusier’s “Towers in a Park” came to life and intersected with planners attempting to impose rationality and “functionalism” to the design of the city and its streets (White, 2016). This intersection resulted in the development of Toronto’s second most identifiable urban form: clusters of ‘slab’ apartment buildings surrounded by open spaces and large amount of surface and underground parking. Large infrastructure projects define this period; from the overhaul of water and wastewater systems to the creation of multi-lane, free-flowing highways

Citizen-led opposition to many of these large-scale projects signaled the end of Toronto’s modernist planning period. Most famously, the American author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs, helped mobilize opposition to the “Spadina Expressway”, which would have run along Spadina Avenue, a broad, prominent avenue that connects many of Toronto’s most beloved neighbourhoods. Shown on plans since the 1943 Metropolitan Area Master Plan, the Province of Ontario cancelled the construction project in 1971. Pressure from local residents garnered political support and the planners of Metro Toronto found themselves becoming more and more impeded in their attempts to build large scale infrastructure on the municipality. If the modernist planning period in Toronto had been typified by deference to expertise, then the time from the early 1970s onward was characterized more by experts looking to citizens for approval (White, 2016). A re-centring of the local over the metropolitan saw planning become more about community engagement. Efforts at urban renewal were slowed and existing low-rise neighbourhoods became impervious to change with each successive Official Plan.

The mid-2000s saw the Province of Ontario release two landmark plans of regional importance: The Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe and the Big Move. They represented a major shift in planning policy for a region that had been sprawling for decades. The Growth Plan designated nodes of density at key locations (designated “urban growth centres”) served by high-order local and regional transit whose future priorities were set out in the Big Move. Municipalities have embraced the challenge, with planning now focused on creating complete communities that are focused on a mixture of uses, mid-rise built forms breaking the monotony of single-family homes or clusters of slab apartment buildings. Mid-rise buildings are particularly encouraged for mixed-use areas the current Toronto Official Plan calls Avenues, many of which are still served by those pre-automotive streetcars lines.

Prioritisation of mental health in urban design and planning in Toronto

The word “health” is commonly found in Toronto planning policy and urban design guidelines. In the Official Plan, variations of the word are used 82 times. Its use is rarely with respect to physical or mental health, however. References to health are fairly evenly distributed amongst economic, environmental, and physical health, health care as a land use, and in platitudinal, non-specific references to a “healthy city” or “healthy neighbourhood”. Nowhere does the concept of “mental health” appear.

That is not to say mental health is completely ignored within Toronto’s planning and urban design frameworks, however. Elements of the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health’s “Mind the GAPS Framework” are addressed throughout the City’s planning and design policies. Since the Official Plan’s approval in 2006, the planning department has completed several detailed design guidelines which reflect a growing understanding of how urban form impacts physical and mental health. Today, the design of new buildings are evaluated based as much on their potential impacts on existing communities and the public realm as their adherence to general design principles. Attention is particularly paid to how the height and shape of a building impact public spaces such as the sidewalk or local parks.

Toronto is experiencing a boom in development, most of which is located close to the urban centre and high- or mid-rise in nature. A departure from Toronto and Ontario’s more traditional single-family housing neighbourhoods, this trend is leading to more and more families living in denser, smaller spaces. Today, almost 70% of families now live in high-density housing (City of Toronto, 2017). Recognizing this, the planning department recently undertook an urban design study called “Growing Up: Planning for Children in New Vertical Communities”. This study, and resulting urban design guidelines, are the clearest sign yet that the City of Toronto is focusing more on how new development can support physical and mental wellbeing.

There are several other examples of the City Planning department promoting wellbeing and health through guidelines, such as guidelines focused on “complete streets”, child care design, neighbourhoods, and accessible design. While not explicitly mentioned, policies and guidelines related to public art and park space reflect an intrinsic understanding among Toronto planning and urban design staff of the importance such spaces are to the overall well-being of Torontonians.

Given the mental health and planning overviews of Toronto, as well as the prioritisation set out in official planning documents, four key themes stand out that warrant further exploration: designing for age, equity and affordability, the use of green space, and complete communities.

That is not to say mental health is completely ignored within Toronto’s planning and urban design frameworks, however. Elements of the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health’s “Mind the GAPS Framework” are addressed throughout the City’s planning and design policies. Since the Official Plan’s approval in 2006, the planning department has completed several detailed design guidelines which reflect a growing understanding of how urban form impacts physical and mental health. Today, the design of new buildings are evaluated based as much on their potential impacts on existing communities and the public realm as their adherence to general design principles. Attention is particularly paid to how the height and shape of a building impact public spaces such as the sidewalk or local parks.

Toronto is experiencing a boom in development, most of which is located close to the urban centre and high- or mid-rise in nature. A departure from Toronto and Ontario’s more traditional single-family housing neighbourhoods, this trend is leading to more and more families living in denser, smaller spaces. Today, almost 70% of families now live in high-density housing (City of Toronto, 2017). Recognizing this, the planning department recently undertook an urban design study called “Growing Up: Planning for Children in New Vertical Communities”. This study, and resulting urban design guidelines, are the clearest sign yet that the City of Toronto is focusing more on how new development can support physical and mental wellbeing.

There are several other examples of the City Planning department promoting wellbeing and health through guidelines, such as guidelines focused on “complete streets”, child care design, neighbourhoods, and accessible design. While not explicitly mentioned, policies and guidelines related to public art and park space reflect an intrinsic understanding among Toronto planning and urban design staff of the importance such spaces are to the overall well-being of Torontonians.

Given the mental health and planning overviews of Toronto, as well as the prioritisation set out in official planning documents, four key themes stand out that warrant further exploration: designing for age, equity and affordability, the use of green space, and complete communities.

Designing for age in Toronto

Toronto’s population is rapidly aging and older adults make up 15% of the population (Rieti, 2017). Older adults have unique urban design needs relating to their mental health and well-being as a result of limited mobility, social isolation and age-specific health and mental health conditions. For example, rates of dementia have been increasing in Canada. This trend will become an increasing burden on the healthcare system, the economy, as well as communities and families. There has been some research looking at the effects of the environment on those living with dementia. Ecotherapy, the therapeutic benefits to nature, may benefit those living with dementia. Some of the proposed benefits include reduced stress, agitation, and depression, as well as improvement in eating and sleeping patterns, memory and attention, sense of wellbeing, and social interaction (Bragg & Atkins, 2016). Despite extensive empirical literature on the benefits of green space exposure among individuals with dementia, there are currently no organizations or projects in Toronto that explore dementia within the context of nature-based interventions.

Another organization targeting both children and older adults is Mood Walks for Campus Health. This provincial program supports exposure to the social, psychological, and physical healing effects of nature among post-secondary students with mental health or social exclusion risk factors. Due to the success and funding of the program, a pilot study dedicated to older adults over the age of 50 has reported meaningful improvements in mental well-being, increased knowledge of local parks and trails, increased confidence, and positive changes in post-walk mood, anxiety, and energy scores (Mood Walks, 2014).

Beyond older adults, the City of Toronto’s Planning Division has recently taken a significant step to improve age-specific initiatives focusing on children. More families with young children have started to live in the city as the population increases, specifically in high density buildings greater than 5 stories. “Growing Up: Planning for Children in New Vertical Communities”, mentioned in the planning overview, may be one of the only urban design guidelines in Toronto that has explicitly identified mental health outcomes as part of its comprehensive framework to improve vertical community living (City of Toronto, 2017). Specifically, the guideline identifies green space, active transportation, and safety as main methods in which to improve mental health outcomes in youth living in the city.

Another organization targeting both children and older adults is Mood Walks for Campus Health. This provincial program supports exposure to the social, psychological, and physical healing effects of nature among post-secondary students with mental health or social exclusion risk factors. Due to the success and funding of the program, a pilot study dedicated to older adults over the age of 50 has reported meaningful improvements in mental well-being, increased knowledge of local parks and trails, increased confidence, and positive changes in post-walk mood, anxiety, and energy scores (Mood Walks, 2014).

Beyond older adults, the City of Toronto’s Planning Division has recently taken a significant step to improve age-specific initiatives focusing on children. More families with young children have started to live in the city as the population increases, specifically in high density buildings greater than 5 stories. “Growing Up: Planning for Children in New Vertical Communities”, mentioned in the planning overview, may be one of the only urban design guidelines in Toronto that has explicitly identified mental health outcomes as part of its comprehensive framework to improve vertical community living (City of Toronto, 2017). Specifically, the guideline identifies green space, active transportation, and safety as main methods in which to improve mental health outcomes in youth living in the city.

Equity and Affordability in Toronto

Housing Affordability and Homelessness

Housing prices in the Greater Toronto Area have becoming more and more unaffordable. Toronto is outpacing Vancouver as the top Canadian city where residents experience difficulties finding affordable housing both for buying and renting (Spoke, 2018; Statistics Canada, 2017). Over one-third of Toronto households spent greater than 30 percent of their income on housing costs in 2016 (Spoke, 2018). As Toronto’s population increases, its housing issues are becoming more similar to other global cities like Hong Kong, Sydney, and London as it climbs the ranks on lists of unaffordability.

The rising housing prices have a significant impact on the mental health of Canadians. A study by Mason et al (2013), found that renters appeared to be more susceptible to the mental health effects of unaffordable housing than home purchasers. Different housing also provides varying degrees of protective factors.

“Higher end housing development places a lot of emphasis on access to transit, green spaces, complete streets. Low-income housing, these factors aren’t being considered. We have a capital repair crisis in this city and across the country in public housing communities.” - Author and placemaker

What is the solution? The province of Ontario has developed a Fair Housing Plan, which includes a foreign-buyers tax and expansion of rent control to a cap of a maximum of 2.5 percent (Ministry of Finance, 2017). However, many academics and housing activists remain skeptical of effectiveness on affordability (Spoke, 2018).

Homelessness and mental health are inextricably linked. Toronto has over 5000 people with no fixed address based on a recent assessment (City of Toronto, 2013). Compared to other cities in North America such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle, Toronto has a lower relative density of homelessness (number per 10,000 residents) that is more similar to that of Boston or Philadelphia (City of Toronto, 2013). People with mental illness are more likely to be underhoused, stay without a home longer, have fewer psychosocial supports, be unemployed, and be in poorer health (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2018). The homeless in Toronto most commonly experience depression and anxiety and not psychotic disorders like schizophrenia as frequently stereotyped. The City of Toronto survey (2013) also showed an increased desire by the homeless population to access mental health services. These services range from substance use related services such as detoxification, alcohol/drug treatment, and harm reduction. Adding to this problem is that many of the underhoused also do not have a family doctor (Khandor, E. et al, 2011).

“If the city keeps growing, there is nowhere for anybody to live...and congestion, how is everybody going to get around? I think that getting people moving and getting people housed are priorities.” - Public health researcher

Race and Equity

Toronto is one of the most racially diverse cities in the world. However, being an immigrant or of non-White ethnicity are risk factors for being homeless. A recent study of Toronto shelter or meal program users found that the most common ethnicity was Black followed by Indigenous (Hwang et al, 2010).

When discussing income and its association with health, examples of areas cited by many interviewees included Regent Park and Alexandra Park. Rejuvenation of these low-income and racially diverse neighbourhoods sometimes require innovative ideas by collaborating with developers.

“Doubling the density pays for the rehab of the old houses… that model has worked quite well [for example in] Alexandra Park.” – Urban designer and professor

In addition, some of the barriers to mental health services often faced by immigrants and newcomers include language and social stigma.

“It’s also important to understand the determinants of mental health...including racism, gender and classism to name a few. Given that many of these determinants are systemic and social in nature a singular design approach would not address these issues. There would really need to be a cross-disciplinary action.” - Author and placemaker

Mental illness is often interpreted, defined and present in different ways. Therefore, in a city like Toronto where newcomers already face barriers, interdisciplinary professionals need to be cognisant of this in order to approach mental illness in a competent and sensitive manner.

“Another thing is cultural competency. For example, the way that Indigenous People[s] would define mental health and wellness is often different from the way it is defined in urbanism. There is a disconnect between architects, planners, etc.” - Author and placemaker

“A lot of the well-intentioned work focuses on social determinants of health. But what we really need to do is go beyond that...what causes racism, is our colonial history and systems of oppression...When we think about cities and when we think about mental health, people automatically think of street-level things...But instead it comes back to how resources are allocated and who has privilege and how does it pan out in a city...we’ll see a pair of $300 earring but on the same street we’ll see someone sleeping on the street. So what does that say about how resources are allocated and what we prioritize?” - Public health researcher

For example, Toronto’s largest mental health institute Centre for Addictions and Mental Health (CAMH) is aware of its struggle and history of stigma. Its name alone has undergone many transformations. It was originally named Provincial Lunatic Asylum when it was opened in 1850 was then renamed multiple times, such as the Asylum for the Insane in 1871 and Hospital for the Insane in 1905, until it became CAMH in 1991. As part of its new Queen Street Redevelopment Project, one of its main mandates is to challenge stigma in its design by integration with the neighbourhood and incorporating green space, therapeutic art installations, and public art by local artists (CAMH, 2018).

To combat some of the barriers mentioned above a tool called the, Health Equity Impact Assessment was developed by the provincial government’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (2013) that is often used in developing new health programs or policies. Its purpose is to ensure there is an appropriate assessment of how different populations would be affected by the proposal. This tool may be useful for developers and planners to incorporate in future design and development.

Involving and empowering racialized individuals may also be beneficial in designing urban spaces.

“There was a woman who came to Canada as a newcomer and she was really disappointed in the lack of green space for her children. So, she created a community movement to create a park, and its thriving. It even has a tandoor oven, so it also has some cultural relevance. As far as I know, it is the most ethno-culturally diverse neighborhoods in Canada. It just goes to show how green spaces evolve differently when it’s community led. I’m a huge believer in not just consultation but genuine community engagement.” - Public health researcher

Housing prices in the Greater Toronto Area have becoming more and more unaffordable. Toronto is outpacing Vancouver as the top Canadian city where residents experience difficulties finding affordable housing both for buying and renting (Spoke, 2018; Statistics Canada, 2017). Over one-third of Toronto households spent greater than 30 percent of their income on housing costs in 2016 (Spoke, 2018). As Toronto’s population increases, its housing issues are becoming more similar to other global cities like Hong Kong, Sydney, and London as it climbs the ranks on lists of unaffordability.

The rising housing prices have a significant impact on the mental health of Canadians. A study by Mason et al (2013), found that renters appeared to be more susceptible to the mental health effects of unaffordable housing than home purchasers. Different housing also provides varying degrees of protective factors.

“Higher end housing development places a lot of emphasis on access to transit, green spaces, complete streets. Low-income housing, these factors aren’t being considered. We have a capital repair crisis in this city and across the country in public housing communities.” - Author and placemaker

What is the solution? The province of Ontario has developed a Fair Housing Plan, which includes a foreign-buyers tax and expansion of rent control to a cap of a maximum of 2.5 percent (Ministry of Finance, 2017). However, many academics and housing activists remain skeptical of effectiveness on affordability (Spoke, 2018).

Homelessness and mental health are inextricably linked. Toronto has over 5000 people with no fixed address based on a recent assessment (City of Toronto, 2013). Compared to other cities in North America such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle, Toronto has a lower relative density of homelessness (number per 10,000 residents) that is more similar to that of Boston or Philadelphia (City of Toronto, 2013). People with mental illness are more likely to be underhoused, stay without a home longer, have fewer psychosocial supports, be unemployed, and be in poorer health (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2018). The homeless in Toronto most commonly experience depression and anxiety and not psychotic disorders like schizophrenia as frequently stereotyped. The City of Toronto survey (2013) also showed an increased desire by the homeless population to access mental health services. These services range from substance use related services such as detoxification, alcohol/drug treatment, and harm reduction. Adding to this problem is that many of the underhoused also do not have a family doctor (Khandor, E. et al, 2011).

“If the city keeps growing, there is nowhere for anybody to live...and congestion, how is everybody going to get around? I think that getting people moving and getting people housed are priorities.” - Public health researcher

Race and Equity

Toronto is one of the most racially diverse cities in the world. However, being an immigrant or of non-White ethnicity are risk factors for being homeless. A recent study of Toronto shelter or meal program users found that the most common ethnicity was Black followed by Indigenous (Hwang et al, 2010).

When discussing income and its association with health, examples of areas cited by many interviewees included Regent Park and Alexandra Park. Rejuvenation of these low-income and racially diverse neighbourhoods sometimes require innovative ideas by collaborating with developers.

“Doubling the density pays for the rehab of the old houses… that model has worked quite well [for example in] Alexandra Park.” – Urban designer and professor

In addition, some of the barriers to mental health services often faced by immigrants and newcomers include language and social stigma.

“It’s also important to understand the determinants of mental health...including racism, gender and classism to name a few. Given that many of these determinants are systemic and social in nature a singular design approach would not address these issues. There would really need to be a cross-disciplinary action.” - Author and placemaker

Mental illness is often interpreted, defined and present in different ways. Therefore, in a city like Toronto where newcomers already face barriers, interdisciplinary professionals need to be cognisant of this in order to approach mental illness in a competent and sensitive manner.

“Another thing is cultural competency. For example, the way that Indigenous People[s] would define mental health and wellness is often different from the way it is defined in urbanism. There is a disconnect between architects, planners, etc.” - Author and placemaker

“A lot of the well-intentioned work focuses on social determinants of health. But what we really need to do is go beyond that...what causes racism, is our colonial history and systems of oppression...When we think about cities and when we think about mental health, people automatically think of street-level things...But instead it comes back to how resources are allocated and who has privilege and how does it pan out in a city...we’ll see a pair of $300 earring but on the same street we’ll see someone sleeping on the street. So what does that say about how resources are allocated and what we prioritize?” - Public health researcher

For example, Toronto’s largest mental health institute Centre for Addictions and Mental Health (CAMH) is aware of its struggle and history of stigma. Its name alone has undergone many transformations. It was originally named Provincial Lunatic Asylum when it was opened in 1850 was then renamed multiple times, such as the Asylum for the Insane in 1871 and Hospital for the Insane in 1905, until it became CAMH in 1991. As part of its new Queen Street Redevelopment Project, one of its main mandates is to challenge stigma in its design by integration with the neighbourhood and incorporating green space, therapeutic art installations, and public art by local artists (CAMH, 2018).

To combat some of the barriers mentioned above a tool called the, Health Equity Impact Assessment was developed by the provincial government’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (2013) that is often used in developing new health programs or policies. Its purpose is to ensure there is an appropriate assessment of how different populations would be affected by the proposal. This tool may be useful for developers and planners to incorporate in future design and development.

Involving and empowering racialized individuals may also be beneficial in designing urban spaces.

“There was a woman who came to Canada as a newcomer and she was really disappointed in the lack of green space for her children. So, she created a community movement to create a park, and its thriving. It even has a tandoor oven, so it also has some cultural relevance. As far as I know, it is the most ethno-culturally diverse neighborhoods in Canada. It just goes to show how green spaces evolve differently when it’s community led. I’m a huge believer in not just consultation but genuine community engagement.” - Public health researcher

Green spaces in Toronto

“We need to have exposure to nature. We don’t necessarily need to have access to massive pieces of real estate…even something like a modest parkette, a little patch of greenness with a bench on a street corner is just as effective on our psychological state of mind as something bigger.” – Psychologist

“There is a huge range of studies that show [viewing green space] can boost mood, help recovery time, [and] support mental health.”- Urban Planner

“There is a huge range of studies that show [viewing green space] can boost mood, help recovery time, [and] support mental health.”- Urban Planner

Figure 2. Queen’s Park, in honour of Queen Victoria, located in an urban area by the Ontario Legislative Building. By Kyle Lee, 2018.

Previous research has suggested positive mental health outcomes associated with green space exposure. These include long-term benefits to time spent in and around tree-lined streets, gardens, and parks (Kuo, 2015). The less access a person has to green space, the higher their chances of morbidity and mortality (Kuo, 2015). Some diseases proposed to be affected include anxiety, depression, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and migraines.

When it comes to green space, the City of Toronto has an abundance of natural space in comparison to some other North American cities. Toronto currently owns over 1,600 parks, covering about 13% of the city’s land area. However, access to green spaces is unevenly distributed within the city, with distribution concentrated mainly in the central areas (Pelley, 2017). One example of this is the city’s downtown core, a booming real estate market that makes it difficult to find land for new parks (Harvey, 2010). Furthermore, a rapidly increasing population puts pressure on balancing protection of green spaces with housing and other developmental opportunities (Pelley, 2017). Therefore, while there are plenty of green spaces in Toronto, uneven access and distribution remains a challenge.

A large part of the city’s park crisis is due to the post-1997 city amalgamation period. For example, staff cuts led to a roughly 50% reduction in summer service capacity. Fortunately, new funding in 2004 led to Toronto Parks and Recreation’s 15-year strategic plan, “Our Common Grounds”. This plan identified a need for reinventing the parks. For example, the “Toronto Parks Renaissance Strategy” helped align parks and trails with the social, economic and cultural needs of residents (Harvey, 2010). Unfortunately, many developments have yet to materialize.

With little in the way of action or funding from the city, Toronto’s parks are currently being supported primarily by community efforts. Some such Toronto groups include The High Park Initiative and Friends of Dufferin Grove Park, to name a few.

If green space is associated with mental health outcomes, access to green space would inextricably also be tied into issues of equity and access.

“When you look at neighborhoods, you can see that lower income neighbourhoods more green space, mental health is poor. On the other hand, higher income neighbourhoods with more green space have better mental health. So we need to look at why, we need to look at public health resources. Why is it that having more green space in higher income neighbourhoods better than in lower income neighbourhoods?” - Public health researcher

Hassen (2016) has argued that these other factors such as safety, the quality of the green space and equitable access is key. For example, the Toronto neighbourhood of Thistletown-Beaumont Heights has an abundance of green space but approximately 60% of residents reported good or excellent mental health. Comparatively, over 80% of those living in West Hill reported excellent mental health despite only average availability of green space. There must be a thoughtful and holistic approach to incorporating green space into city spaces to ensure maximal health benefits.

When it comes to green space, the City of Toronto has an abundance of natural space in comparison to some other North American cities. Toronto currently owns over 1,600 parks, covering about 13% of the city’s land area. However, access to green spaces is unevenly distributed within the city, with distribution concentrated mainly in the central areas (Pelley, 2017). One example of this is the city’s downtown core, a booming real estate market that makes it difficult to find land for new parks (Harvey, 2010). Furthermore, a rapidly increasing population puts pressure on balancing protection of green spaces with housing and other developmental opportunities (Pelley, 2017). Therefore, while there are plenty of green spaces in Toronto, uneven access and distribution remains a challenge.

A large part of the city’s park crisis is due to the post-1997 city amalgamation period. For example, staff cuts led to a roughly 50% reduction in summer service capacity. Fortunately, new funding in 2004 led to Toronto Parks and Recreation’s 15-year strategic plan, “Our Common Grounds”. This plan identified a need for reinventing the parks. For example, the “Toronto Parks Renaissance Strategy” helped align parks and trails with the social, economic and cultural needs of residents (Harvey, 2010). Unfortunately, many developments have yet to materialize.

With little in the way of action or funding from the city, Toronto’s parks are currently being supported primarily by community efforts. Some such Toronto groups include The High Park Initiative and Friends of Dufferin Grove Park, to name a few.

If green space is associated with mental health outcomes, access to green space would inextricably also be tied into issues of equity and access.

“When you look at neighborhoods, you can see that lower income neighbourhoods more green space, mental health is poor. On the other hand, higher income neighbourhoods with more green space have better mental health. So we need to look at why, we need to look at public health resources. Why is it that having more green space in higher income neighbourhoods better than in lower income neighbourhoods?” - Public health researcher

Hassen (2016) has argued that these other factors such as safety, the quality of the green space and equitable access is key. For example, the Toronto neighbourhood of Thistletown-Beaumont Heights has an abundance of green space but approximately 60% of residents reported good or excellent mental health. Comparatively, over 80% of those living in West Hill reported excellent mental health despite only average availability of green space. There must be a thoughtful and holistic approach to incorporating green space into city spaces to ensure maximal health benefits.

Figure 3. Victorian rowhouses in a quiet residential street near Trinity Bellwoods Park. By Kyle Lee, 2016.

Complete communities in Toronto

“Central to our mission is the creation of ‘complete communities’...making sure that there is choice and diversity in every neighbourhood, that the full range of needs are being met.” - Urban designer

Figure 4. The Dominion Public Building near Union Station, Toronto’s main train station, with the iconic CN tower in the background. By Kyle Lee, 2016.

Much of Toronto’s development has been either low-density or high-rise apartments. Studies have shown that both housing types can come with mental health risks and different types of social isolation (Sturm & Cohen, 2004; Luciano et al., 2016). In an effort to improve the quality of urban environments, the Ontario’s provincial Growth Plan emphasizes the need to create “complete communities”. Complete communities are “mixed-use neighbourhoods or other areas within cities… that offer and support opportunities for people of all ages and abilities to conveniently access most of the necessities for daily living, including an appropriate mix of jobs, local stores, and services, a full range of housing, transportation options, and public service facilities” (Growth Plan, 2017).

The City of Toronto has made great strides in adhering to the goals in the Growth Plan. The principles of complete communities can be found in many of the new developments the City is approving. In previous planning eras, whole neighbourhoods were built that consisted of only one type of housing or built form. This was true whether the neighbourhoods consisted of single-detached family housing or apartment buildings. In following the idea of complete communities, planners are now focused on ensuring a range of housing types as well as tenure (i.e. ownership versus rental housing). In doing so, neighbourhoods cater to a range of classes instead of one particular socio-economic class. These policies limit the stigma attached by the creation of low-income communities, as well as any subsequent impacts this has on mental health. Creating mixed-income, complete communities can mitigate against the mental health risks associated with poverty by ensuring safer neighbourhoods and better access to public amenities (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2007) (See also: Equity/Affordable Housing section).

“Developments that are truly community-generated allow citizens to have greater ownership over neighbourhood change, which is positive for mental health” - Architect

Central to the creation of complete communities is the community engagement process. Toronto is in the middle of an unprecedented development boom and many neighbourhoods are undergoing substantial changes. Supporting existing residents as part of this process leads to better outcomes and more complete communities according to interviewees. Concerns raised by communities often centre on size and location of green and open space, adequate levels of social and community services, as well as safety, which may all be associated with mental health outcomes. Examples of complete communities in Toronto include the Regent Park redevelopment, Mirvish Village, the Tower Renewal project, the 6-points intersection realignment, and the Canary District. Overall, the City of Toronto has made great strides in improving the community engagement process.

The City of Toronto has made great strides in adhering to the goals in the Growth Plan. The principles of complete communities can be found in many of the new developments the City is approving. In previous planning eras, whole neighbourhoods were built that consisted of only one type of housing or built form. This was true whether the neighbourhoods consisted of single-detached family housing or apartment buildings. In following the idea of complete communities, planners are now focused on ensuring a range of housing types as well as tenure (i.e. ownership versus rental housing). In doing so, neighbourhoods cater to a range of classes instead of one particular socio-economic class. These policies limit the stigma attached by the creation of low-income communities, as well as any subsequent impacts this has on mental health. Creating mixed-income, complete communities can mitigate against the mental health risks associated with poverty by ensuring safer neighbourhoods and better access to public amenities (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2007) (See also: Equity/Affordable Housing section).

“Developments that are truly community-generated allow citizens to have greater ownership over neighbourhood change, which is positive for mental health” - Architect

Central to the creation of complete communities is the community engagement process. Toronto is in the middle of an unprecedented development boom and many neighbourhoods are undergoing substantial changes. Supporting existing residents as part of this process leads to better outcomes and more complete communities according to interviewees. Concerns raised by communities often centre on size and location of green and open space, adequate levels of social and community services, as well as safety, which may all be associated with mental health outcomes. Examples of complete communities in Toronto include the Regent Park redevelopment, Mirvish Village, the Tower Renewal project, the 6-points intersection realignment, and the Canary District. Overall, the City of Toronto has made great strides in improving the community engagement process.

Figure 5, Kensington Market, a popular neighbourhood during their once monthly summer street festival. By Kyle Lee, 2016.

Case Studies

We picked out two examples of how Toronto planning meets the goals of the Centre for Urban Design’s Mind the GAPS Framework, despite not prioritising mental health explicitly within official planning policy.

Case Study 1: 6-Points Interchange Reconfiguration

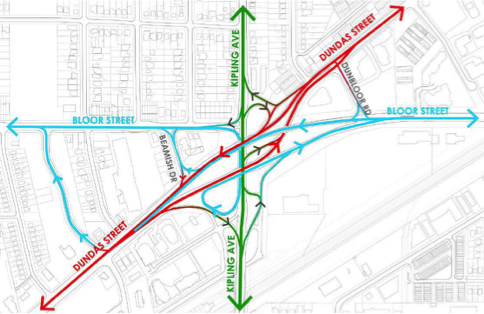

Figure 6. Reconfiguration of The Six Points Interchange, Community Update #2. By City of Toronto, 2014.

The 6-Points Interchange Reconfiguration may sound like an infrastructure renewal project, but it is primarily focused on creating a more complete community. After more than 10 years of planning, community consultation, engineering, and design, a major intersection in Toronto known for being dangerously hostile to pedestrians, with little to no public space on offer, is being transformed. Reconfiguring the intersection is intended to allow the creation of a “vibrant, mixed-use transit-oriented community” that new pedestrian facilities, wider boulevards, more trees and street furniture, improved cycling access and facilities, new parks, public art, and even a district energy plan (City of Toronto, 2014).

The current 6-points intersection is an example of old infrastructure decisions based solely on facilitating the free movement of traffic. As a result of the intersection reconfiguration, the City of Toronto is able to relocate a key civic building offering community services to a more accessible and pedestrian-friendly location. The substantial effort and community consultation that went into realigning the intersection is a demonstration of the City of Toronto’s commitment to delivering on the idea of complete communities, and particularly on how it plans to use public space to improve community wellbeing.

The current 6-points intersection is an example of old infrastructure decisions based solely on facilitating the free movement of traffic. As a result of the intersection reconfiguration, the City of Toronto is able to relocate a key civic building offering community services to a more accessible and pedestrian-friendly location. The substantial effort and community consultation that went into realigning the intersection is a demonstration of the City of Toronto’s commitment to delivering on the idea of complete communities, and particularly on how it plans to use public space to improve community wellbeing.

Figure 7. Reconfiguration of The Six Points Interchange, Community Update #2. By City of Toronto, 2014.

The new streetscape resulting from the 6-Points Interchange Reconfiguration creates a much more hospitable and welcoming environment for pedestrians, helping achieve the Mind the GAPS Framework.

Green places: Redesign of an over-engineered intersection into a new network of streets that allow for an increase in the number of parks and open spaces.

Active places: Taking an area designed simply for the movement of cars and turning it into a space designed for pedestrians and cyclists.

Pro-Social places: Redesign of the street network allows for dedicated spaces for public art, new street furniture, and greater accessibility.

Safe places: Current design of the intersection is very inhospitable to pedestrians and cyclists. The intersection is unsafe due to the high volume and speed of vehicles, but also because of the lack of “eyes on the street”. Redesign of the intersection will greater enhance the look and feel of the area.

Green places: Redesign of an over-engineered intersection into a new network of streets that allow for an increase in the number of parks and open spaces.

Active places: Taking an area designed simply for the movement of cars and turning it into a space designed for pedestrians and cyclists.

Pro-Social places: Redesign of the street network allows for dedicated spaces for public art, new street furniture, and greater accessibility.

Safe places: Current design of the intersection is very inhospitable to pedestrians and cyclists. The intersection is unsafe due to the high volume and speed of vehicles, but also because of the lack of “eyes on the street”. Redesign of the intersection will greater enhance the look and feel of the area.

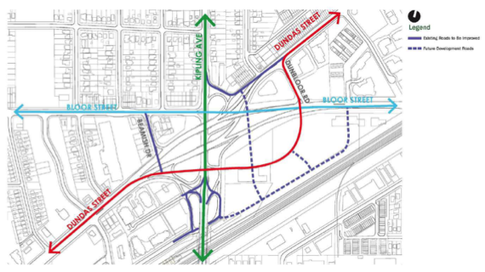

Case study 2: Tower Renewal Project

Figure 8. Tower Renewal Project. From City of Toronto, 2018, www.raczone.com, Copyright by Daniel Rotsztain, City of Toronto.

Toronto’s post-war apartment clusters (described in the Planning Overview) began to show signs of aging by the turn of the century. Though valuable sources of affordable rental housing in Toronto, these neighbourhoods often lacked the multi-use zoning and public spaces needed to create safe and welcoming urban spaces. The Tower Renewal project was established as a response to these challenges by Toronto-based architects Graeme Stewart and Michael McClelland. Now called the Toronto Renewal Partnership, this initiative is a multi-sectoral collaboration including multiple local governments and NGOs. In an effort to create more complete communities, the Tower Renewal project has helped revitalize many post-war apartment communities through a mixture of community engagement, economic development, and local capacity-building in addition to much-needed building improvements.

To date, there has not been any research on how the project has helped improve the mental health of the residents of Tower Renewal communities. Using the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health Mind the GAPS Framework, however, the Tower Renewal project provides a terrific example of how urban spaces can be revitalized without wholescale redevelopment. By emphasizing community engagement and existing community assets, the factors contributing to better mental health be created in places where they currently do not exist.

The Tower Renewal project creates more opportunities for economic development, such as this neighbourhood market in Toronto’s Thorncliffe Park.

To date, there has not been any research on how the project has helped improve the mental health of the residents of Tower Renewal communities. Using the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health Mind the GAPS Framework, however, the Tower Renewal project provides a terrific example of how urban spaces can be revitalized without wholescale redevelopment. By emphasizing community engagement and existing community assets, the factors contributing to better mental health be created in places where they currently do not exist.

The Tower Renewal project creates more opportunities for economic development, such as this neighbourhood market in Toronto’s Thorncliffe Park.

Figure 9. A market found in theThorncliffe Park neighbourhood of Toronto. From ERA Architects, 2018, The Globe and Mail, Copyright by Daniel Rotsztain, 2017.

Green places: while most Tower Renewal sites are apartment building clusters surrounded by large amounts of green space, the quality of these green spaces often leaves much to be desired. Often these spaces are neglected and unwelcoming to visitors. The Tower Renewal project improves the quality and programming of green spaces for residents

Active places: In addition to improving the quality of green spaces, Tower Renewal also improves active transportation connections to existing parks, schools, and neighbourhood amenities.

Pro-Social places: The greatest strength of the Tower Renewal project is that it creates new opportunities for the communities to come together through the use of economic development spaces. By introducing resident-generated markets, Tower Renewal provides more opportunities for residents to interact.

Safe places: By improving the potential for community interaction, the Tower Renewal project greatly enhances the feeling of safety in its neighbourhoods.

Active places: In addition to improving the quality of green spaces, Tower Renewal also improves active transportation connections to existing parks, schools, and neighbourhood amenities.

Pro-Social places: The greatest strength of the Tower Renewal project is that it creates new opportunities for the communities to come together through the use of economic development spaces. By introducing resident-generated markets, Tower Renewal provides more opportunities for residents to interact.

Safe places: By improving the potential for community interaction, the Tower Renewal project greatly enhances the feeling of safety in its neighbourhoods.

SWOT analysis: urban design for mental health in Toronto

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

|

Opportunities |

Threats |

|

|

Conclusion

Certain factors affect mental health and well-being of urbanites living in Toronto, notably immigration, education, stigma, and access to services. From our research and interview data, certain themes such as age, race and equity, green spaces, and complete communities have emerged that provide insight into how urban design may also impact mental health. Specific examples of various communities and developments around Toronto have also demonstrated how design has begun to affect the mental health status of citizens. Future research, policy, and urban development should highlight the aforementioned four themes as a framework in order to promote healthy and vibrant urban design.

Lessons from Toronto that could be applied to promote wellbeing and good mental health through urban planning and design in other cities

1. Focus on specific demographic challenges: A range of factors need to be considered in planning initiatives such as age, race and equity, green spaces, and complete communities. Toronto's age-specific guidelines are an example for other cities to follow. More work needs to be done in understanding the mental health challenges impacting on specific demographics and geographies.

2. Build complete communities: Toronto has made great strides in creating complete communities and can provide lessons for other cities. There is still much work to be done, however, on ensuring inclusivity for people of all ages and abilities, such as children, the elderly, and those with particular needs (eg. immigrants, those with dementia, etc.) and their mental well-being.

3. Public Art: Always provide space and funding for public art in new developments to allow for moments of reflection and quiet amongst the bustle of city-life. Therapeutic art, in particular, can help ease the impacts of urban living on mental health. Toronto is taking public art to new levels and is merging it with ideas of public space in new and innovative ways.

4. Integrate mental health facilities into the city: Do not create stand-alone campuses or facilities. Integrating their design and making them part of the city itself can ease the stigma associated with mental illness.

5. Reimagine infrastructure: Improving the scale and design of civic infrastructure can help the feeling of safety and alleviate isolation for those living within close proximity.

1. Focus on specific demographic challenges: A range of factors need to be considered in planning initiatives such as age, race and equity, green spaces, and complete communities. Toronto's age-specific guidelines are an example for other cities to follow. More work needs to be done in understanding the mental health challenges impacting on specific demographics and geographies.

2. Build complete communities: Toronto has made great strides in creating complete communities and can provide lessons for other cities. There is still much work to be done, however, on ensuring inclusivity for people of all ages and abilities, such as children, the elderly, and those with particular needs (eg. immigrants, those with dementia, etc.) and their mental well-being.

3. Public Art: Always provide space and funding for public art in new developments to allow for moments of reflection and quiet amongst the bustle of city-life. Therapeutic art, in particular, can help ease the impacts of urban living on mental health. Toronto is taking public art to new levels and is merging it with ideas of public space in new and innovative ways.

4. Integrate mental health facilities into the city: Do not create stand-alone campuses or facilities. Integrating their design and making them part of the city itself can ease the stigma associated with mental illness.

5. Reimagine infrastructure: Improving the scale and design of civic infrastructure can help the feeling of safety and alleviate isolation for those living within close proximity.

Recommendations for Toronto to improve public mental health and wellbeing through urban planning and design

1. Prioritize mental health in policy: Emphasize mental health in official planning and urban design policy documents. As Toronto grows denser and more populous, it needs to develop explicit planning policy prioritizing mental health for a diversity of ages and populations that matches the city’s ever-changing demographic and landscape.

2. Collaborate with health care and other professionals: Comprehensive design should be collaborative between all stakeholders, including public health professionals, designers, urban planners, mental health specialists, citizens, and other interest groups.

3. Improve the variety of built form: Many Toronto neighbourhoods are either single-detached housing or clusters of apartment buildings. Toronto needs to improve the variety of housing types to help reduce social isolation and improve mental health.

4. More emphasis on equity of public spaces: High quality green and public spaces that ensure equitable access to those of different backgrounds and income levels are important to prevent segregation and improve mental health outcomes to all citizens.

5. Tackle affordability: As cost of living increases in Toronto, affordable housing is key to promoting and maintaining positive mental health on a city-wide level.

1. Prioritize mental health in policy: Emphasize mental health in official planning and urban design policy documents. As Toronto grows denser and more populous, it needs to develop explicit planning policy prioritizing mental health for a diversity of ages and populations that matches the city’s ever-changing demographic and landscape.

2. Collaborate with health care and other professionals: Comprehensive design should be collaborative between all stakeholders, including public health professionals, designers, urban planners, mental health specialists, citizens, and other interest groups.

3. Improve the variety of built form: Many Toronto neighbourhoods are either single-detached housing or clusters of apartment buildings. Toronto needs to improve the variety of housing types to help reduce social isolation and improve mental health.

4. More emphasis on equity of public spaces: High quality green and public spaces that ensure equitable access to those of different backgrounds and income levels are important to prevent segregation and improve mental health outcomes to all citizens.

5. Tackle affordability: As cost of living increases in Toronto, affordable housing is key to promoting and maintaining positive mental health on a city-wide level.

References

Bell Canada (2015). Bell Let’s Talk: The first 5 years (2010-2015). Retrieved from http://letstalk.bell.ca/letstalkprogressreport.

Boak et al. (2016). The mental health and well-being of Ontario students, 1991-2015: Detailed OSDUHS findings. CAMH Research Document Series no. 43. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Bragg, R., & Atkins, G. (2016). A review of nature-based interventions for mental health care. Natural England Commissioned Reports, Number 204. Retrieved from: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/file/6567580331409408

Brien et al. (2015). Taking Stock: A report on the quality of mental health and addictions services in Ontario. An HQO/ICES Report. Toronto: Health Quality Ontario and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

Canadian Mental Health Association (2007). Poverty and Mental Illness. Retrieved from: https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/poverty-and-mental-illness/

Canadian Mental Health Association. (2018). Homelessness. Retrieved from https://cmha.ca/public-policy/subject/homelessness

Canadian Community Health Survey: Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), 2007 to 2014. Statistics Canada, Share File, Knowledge Management and Rating Branch, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.