|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2020:6;6

|

RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS

Is all nature equal? Evaluating the role of familiarity on emotional responses to nature.

Kathryn Terzano (1) and Alina Gross (2)

(1) Iowa State University, USA

(2) Westfield State University, USA

(2) Westfield State University, USA

Abstract

People's attachment to nature has important relevance to the understanding of nature’s influence on mental health, but in terms of impact, is all nature equal? This study seeks to understand the affective responses of exposure to images of nature across geographically-diverse university student populations. Familiarity with certain kinds of scenery may help people to feel more positively about them and, in some cases, even prefer them. Understanding these preferences is one way to help people to cope with the current and future crises. In choosing appropriate designs, it is important for design professionals to understand the extent to which nature scenes, whether photographs, murals on buildings, paintings, landscape design elements, or some other form, elicit affective responses.

A total of 227 student respondents, grouped based on their geographical location of residence, rated photographs of desert landscapes, green hills, and mountain scenes. They rated the photographs for attractiveness, chose preferred images among sets of scenes, and gave an affective rating of Very Exciting to Very Relaxing for their chosen images. In this study, respondents from the Southwest region of the USA rated desert landscaping as more attractive than did respondents from New England. Overall, mountain scenes were rated as the most attractive type of scene by all respondents and were also most likely to be chosen as the preferred images. For all groups of respondents, hills were more likely to be rated as relaxing than exciting, deserts were more likely to be rated as exciting than relaxing, and mountains were almost as likely to be rated as relaxing as they were to be rated as exciting.

We were particularly interested in students’ responses to nature scenes because university students are a vulnerable group for mental health struggles. With COVID-19 and other future crises, viewing scenes of nature may be a coping mechanism to provide stress relief. Future studies may wish to add a physiological component to assess whether viewing nature scenes has a measurable effect on stress hormones.

Practical implications: Understanding the affective responses to different kinds of nature can help urban designers, landscape architects, and other design professionals to create appropriate opportunities to view and be part of nature. For example, for an urban designer in a certain location, knowing the likely local affective responses to a desert rock garden compared to a lush oasis of non-native species, or perhaps even of a mural of a mountain scene, can inform which is the more appropriate choice for the desired affective response, such as feeling stress relief and relaxation. Such professionals, whether designing for people in their geographic area or for the public in general, would also benefit from knowing which kinds of nature scenes are perceived to be more attractive.

A total of 227 student respondents, grouped based on their geographical location of residence, rated photographs of desert landscapes, green hills, and mountain scenes. They rated the photographs for attractiveness, chose preferred images among sets of scenes, and gave an affective rating of Very Exciting to Very Relaxing for their chosen images. In this study, respondents from the Southwest region of the USA rated desert landscaping as more attractive than did respondents from New England. Overall, mountain scenes were rated as the most attractive type of scene by all respondents and were also most likely to be chosen as the preferred images. For all groups of respondents, hills were more likely to be rated as relaxing than exciting, deserts were more likely to be rated as exciting than relaxing, and mountains were almost as likely to be rated as relaxing as they were to be rated as exciting.

We were particularly interested in students’ responses to nature scenes because university students are a vulnerable group for mental health struggles. With COVID-19 and other future crises, viewing scenes of nature may be a coping mechanism to provide stress relief. Future studies may wish to add a physiological component to assess whether viewing nature scenes has a measurable effect on stress hormones.

Practical implications: Understanding the affective responses to different kinds of nature can help urban designers, landscape architects, and other design professionals to create appropriate opportunities to view and be part of nature. For example, for an urban designer in a certain location, knowing the likely local affective responses to a desert rock garden compared to a lush oasis of non-native species, or perhaps even of a mural of a mountain scene, can inform which is the more appropriate choice for the desired affective response, such as feeling stress relief and relaxation. Such professionals, whether designing for people in their geographic area or for the public in general, would also benefit from knowing which kinds of nature scenes are perceived to be more attractive.

Introduction

People's attachment to nature and landscape features has important relevance to the understanding of nature’s influence on mental health. A recent scoping review of published articles and books on the mental health of U.S. university students found that as little as ten minutes’ daily exposure to nature has a positive effect on mental health (Meredith, et al. 2020). Other research has explored the mental health and wellbeing of individuals when exposed to nature more generally (Kaplan and Kaplan 1989), greenspace, and biodiversity (Fuller, et al. 2007). Furthermore, researchers have long known that even having a view of nature, such as through a hospital room window, may aid in recovery (R. S. Ulrich 1984). In times of crisis, such as recently with COVID-19, some people have sought to access the physical and mental health benefits of outdoor activities in nature environments, but is all nature equal? Understanding people's emotional responses to exposure to different types of nature could be relevant in developing urban planning and design strategy to support people's mental wellbeing.

Landscape preference, and the psychological connections that exist between people and place, has become an increasingly important topic for researchers not just in mental health, but also in the fields of planning, conservation, environmental psychology, geography, and related disciplines. In the field of planning, place attachment can be an important element in understanding how to maintain or improve quality of life for neighborhoods, towns, or cities, or how to gain local support related to residential development, recreation or conservation. For example, Walker and Ryan’s (2008) study on place attachment in the context of landscape preservation in rural Maine in the US ascertained residents’ level of attachment to various landscapes and how this related to their willingness to become involved with local conservation efforts. Scannell and Gifford’s (2011) study looked at the connection between place attachment and community member’s engagement in climate change issues, finding that climate change engagement was greater among those more attached to local areas (2011). With increasing mobility and ability to move to varying climates from where we originated, understanding landscape preference, and specifically the influence of familiarity on landscape preference, could help individuals understand potential effects on their mental health and overall environmental satisfaction when relocating.

This study seeks to understand the affective responses of exposure to images of nature across geographically diverse university-aged populations. Such knowledge could be relevant in strategizing how and where to create natural spaces on college campuses and beyond that can positively impact the mental wellness of university students in times of COVID-19 and beyond.

Studies have consistently found that people have a preference for environments perceived as natural to those perceived as human-made (Kaplan, 1987; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Kaplan, Kaplan, & Wendt, 1972; Lamb & Purcell, 1990; Nasar, 1994). In such studies, “natural” has related to the presence green elements – foliage, vegetation, and trees – as well as the absence of overt human intervention (Herzog, Kaplan, & Kaplan, 1982; Ulrich, 1986). Other relevant studies have explored other types of exposure to nature views or experiences such as, for example, the influence of blue spaces (Nutsford, et al. 2016) (Bell, et al. 2015) or sand therapy (Wang, Cui and Xu 2018). This study explores the extent to which where a person lives and the landscapes with which they are most familiar may impact their environmental aesthetic preferences and the particular affects associated with those preferences, by asking participants to rate desert scenes versus mountain scenes.

This study also explores the issue of associating green with “naturalness” by exploring the differences in attachment to the landscapes from varying geographic areas of the country. While previous studies have found perceived naturalness has been correlated with the presence of green growth, this type of naturally green landscape is not actually present in many geographic regions of the the United States, some regions have little to no green in the natural landscape. We examine whether a substantial amount of green plant and tree growth is integral to a connection to with a natural scene by showing participants photographic scenes that include more mountainous scenes with a greener and tree-focused setting as well as desert scenes that do not feature a lot of green growth.

We hypothesize that respondents living in the Southwest—an area of the United States that is largely devoid of green, forested areas and instead characterized by deserts with shrubbery and cacti—would find images of the Southwest to be more attractive than respondents from other areas find them to be. Previous work by Lyons (1983) found a connection between familiarity with a landscape, or biome, and individuals’ preferences for living in and visiting such a place, but did not address whether people from particular areas of the country have an aesthetic preference for their area. Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibanez (2010) also found that familiarity was related to preference, and further that their sample shows a preference for lush green landscapes; however, their sample included respondents in villages in an area of Northern Spain where a lush green landscape predominates. Lyons (1983) and Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibanez (2010) provide evidence that contradicts landscape preference being innate, with green landscapes being “naturally” preferred (see Balling & Falk, 1982). Other notable studies have looked at the way natural information is processed in the context of landscape preference and perception of natural beauty (Joye and van de Berg 2011) (Medidenbauer, et al. 2019) (Hagerhall , Purcell and Taylor 2004).

Important research relevant to this study has addressed emotional response to nature in a variety of ways including emotional connection with nature as a basis for environmental protection (Kals, Schumacher and Montada 1999), methods of measuring an individual’s connection to nature (Mayer and Frantz 2004) (Perrin and Benassi 2009), and more specifically, emotional connection to natural elements such as trees (Sheets and Manzer 1991) (Mohamed, et al. 2013) (Lo and Jim 2015).

The social construction of nature is also relevant to this study. The way our society depicts natural scenes via various media outlets such as children’s shows, picture books and so forth may influence what we see as a relaxing environment versus an exciting environment (Robbins, Hintz and Moore 2014). The social construction of nature, and in particular its relationship to risk perception has been explored (Karl 1992) while research related to landscape perception and the social construction of nature is significantly more limited. Further, it is probable that if one is raised within a particular landscape, they may better understand it, both through formal environmental education as well as through play and leisure-time exploration of their natural environments.

Landscape preference, and the psychological connections that exist between people and place, has become an increasingly important topic for researchers not just in mental health, but also in the fields of planning, conservation, environmental psychology, geography, and related disciplines. In the field of planning, place attachment can be an important element in understanding how to maintain or improve quality of life for neighborhoods, towns, or cities, or how to gain local support related to residential development, recreation or conservation. For example, Walker and Ryan’s (2008) study on place attachment in the context of landscape preservation in rural Maine in the US ascertained residents’ level of attachment to various landscapes and how this related to their willingness to become involved with local conservation efforts. Scannell and Gifford’s (2011) study looked at the connection between place attachment and community member’s engagement in climate change issues, finding that climate change engagement was greater among those more attached to local areas (2011). With increasing mobility and ability to move to varying climates from where we originated, understanding landscape preference, and specifically the influence of familiarity on landscape preference, could help individuals understand potential effects on their mental health and overall environmental satisfaction when relocating.

This study seeks to understand the affective responses of exposure to images of nature across geographically diverse university-aged populations. Such knowledge could be relevant in strategizing how and where to create natural spaces on college campuses and beyond that can positively impact the mental wellness of university students in times of COVID-19 and beyond.

Studies have consistently found that people have a preference for environments perceived as natural to those perceived as human-made (Kaplan, 1987; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Kaplan, Kaplan, & Wendt, 1972; Lamb & Purcell, 1990; Nasar, 1994). In such studies, “natural” has related to the presence green elements – foliage, vegetation, and trees – as well as the absence of overt human intervention (Herzog, Kaplan, & Kaplan, 1982; Ulrich, 1986). Other relevant studies have explored other types of exposure to nature views or experiences such as, for example, the influence of blue spaces (Nutsford, et al. 2016) (Bell, et al. 2015) or sand therapy (Wang, Cui and Xu 2018). This study explores the extent to which where a person lives and the landscapes with which they are most familiar may impact their environmental aesthetic preferences and the particular affects associated with those preferences, by asking participants to rate desert scenes versus mountain scenes.

This study also explores the issue of associating green with “naturalness” by exploring the differences in attachment to the landscapes from varying geographic areas of the country. While previous studies have found perceived naturalness has been correlated with the presence of green growth, this type of naturally green landscape is not actually present in many geographic regions of the the United States, some regions have little to no green in the natural landscape. We examine whether a substantial amount of green plant and tree growth is integral to a connection to with a natural scene by showing participants photographic scenes that include more mountainous scenes with a greener and tree-focused setting as well as desert scenes that do not feature a lot of green growth.

We hypothesize that respondents living in the Southwest—an area of the United States that is largely devoid of green, forested areas and instead characterized by deserts with shrubbery and cacti—would find images of the Southwest to be more attractive than respondents from other areas find them to be. Previous work by Lyons (1983) found a connection between familiarity with a landscape, or biome, and individuals’ preferences for living in and visiting such a place, but did not address whether people from particular areas of the country have an aesthetic preference for their area. Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibanez (2010) also found that familiarity was related to preference, and further that their sample shows a preference for lush green landscapes; however, their sample included respondents in villages in an area of Northern Spain where a lush green landscape predominates. Lyons (1983) and Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibanez (2010) provide evidence that contradicts landscape preference being innate, with green landscapes being “naturally” preferred (see Balling & Falk, 1982). Other notable studies have looked at the way natural information is processed in the context of landscape preference and perception of natural beauty (Joye and van de Berg 2011) (Medidenbauer, et al. 2019) (Hagerhall , Purcell and Taylor 2004).

Important research relevant to this study has addressed emotional response to nature in a variety of ways including emotional connection with nature as a basis for environmental protection (Kals, Schumacher and Montada 1999), methods of measuring an individual’s connection to nature (Mayer and Frantz 2004) (Perrin and Benassi 2009), and more specifically, emotional connection to natural elements such as trees (Sheets and Manzer 1991) (Mohamed, et al. 2013) (Lo and Jim 2015).

The social construction of nature is also relevant to this study. The way our society depicts natural scenes via various media outlets such as children’s shows, picture books and so forth may influence what we see as a relaxing environment versus an exciting environment (Robbins, Hintz and Moore 2014). The social construction of nature, and in particular its relationship to risk perception has been explored (Karl 1992) while research related to landscape perception and the social construction of nature is significantly more limited. Further, it is probable that if one is raised within a particular landscape, they may better understand it, both through formal environmental education as well as through play and leisure-time exploration of their natural environments.

Methods

Participants

Participants were enrolled in one of four urban planning and geography courses through two public universities in the United States: one university in New England and one university in the Southwest. All students enrolled in the four courses were asked to complete the survey in exchange for extra credit points in the course worth one percent of the final course grade. The courses were taught entirely online and, as such, participants were physically located in 16 different states. For the purposes of analysis, we grouped the states into categories: Southwest, New England, and Other. 65 respondents (28.6%) fell into the Southwest category; 71 respondents (31.3%) were in the New England category; and 91 respondents (40.1%) were in the Other category, representing U.S. states other than those in the Southwest or New England. The Other group included respondents whose home environment, based on the city-level data provided they on the survey, was not neither the desert nor hills. This allowed for a comparison group.

Stimuli

Participants were shown 18 digital color photographs in total of which six photographs were of actual desert landscapes found in the Southwest U.S., six photographs were of green, rolling hills that typify non-urban parts of New England, and six photographs were of rocky mountains (see Figure 1). We chose images that were freely available through Google images, selecting images that were representative of the three landscapes of interest and that were similar in terms of quality, density, proportion of foreground, and that had not been artistically altered or Photoshopped. Six images of each type were chosen so that we could assess ratings across each type of image and, if needed, exclude any images that were rated significantly higher or lower than others of their type. None of the images had any visible presence of water, buildings, or humans or other animals, and additionally we altered the photographs to have a similar degree of brightness and overall framing. It should be noted that all images contained plants and some amount of greenery, such as desert sagebrush in the desert photographs and grass in the foreground of the mountain photographs. The administration of sets of color photographs in this manner is consistent with previous methods used by Nasar and Terzano (2010) to elicit people’s perceptions of natural environments.

The use of photographs served a pragmatic purpose of providing stimuli for the respondents to rate without having to travel in person to different kinds of landscapes. Beyond this study, travel to other landscapes is also not equally available to all people due to personal limitations (e.g., income or time), and during times of crisis, like with COVID-19, there may also be travel restrictions in place that prevent people from traveling to their preferred locations. Not all people have equal access to nature, including the kind of nature (mountains, desert, and so on) that they might enjoy most, and there are also differences in access within individual urban areas, where not everyone has equal access to recreational areas or parks. Thus, it is important for urban designers and researchers to understand which scenes of nature, whether photographs, murals on the sides of buildings, or some other form, people prefer and whether different scenes of nature can elicit different affective responses as well.

Participants were enrolled in one of four urban planning and geography courses through two public universities in the United States: one university in New England and one university in the Southwest. All students enrolled in the four courses were asked to complete the survey in exchange for extra credit points in the course worth one percent of the final course grade. The courses were taught entirely online and, as such, participants were physically located in 16 different states. For the purposes of analysis, we grouped the states into categories: Southwest, New England, and Other. 65 respondents (28.6%) fell into the Southwest category; 71 respondents (31.3%) were in the New England category; and 91 respondents (40.1%) were in the Other category, representing U.S. states other than those in the Southwest or New England. The Other group included respondents whose home environment, based on the city-level data provided they on the survey, was not neither the desert nor hills. This allowed for a comparison group.

Stimuli

Participants were shown 18 digital color photographs in total of which six photographs were of actual desert landscapes found in the Southwest U.S., six photographs were of green, rolling hills that typify non-urban parts of New England, and six photographs were of rocky mountains (see Figure 1). We chose images that were freely available through Google images, selecting images that were representative of the three landscapes of interest and that were similar in terms of quality, density, proportion of foreground, and that had not been artistically altered or Photoshopped. Six images of each type were chosen so that we could assess ratings across each type of image and, if needed, exclude any images that were rated significantly higher or lower than others of their type. None of the images had any visible presence of water, buildings, or humans or other animals, and additionally we altered the photographs to have a similar degree of brightness and overall framing. It should be noted that all images contained plants and some amount of greenery, such as desert sagebrush in the desert photographs and grass in the foreground of the mountain photographs. The administration of sets of color photographs in this manner is consistent with previous methods used by Nasar and Terzano (2010) to elicit people’s perceptions of natural environments.

The use of photographs served a pragmatic purpose of providing stimuli for the respondents to rate without having to travel in person to different kinds of landscapes. Beyond this study, travel to other landscapes is also not equally available to all people due to personal limitations (e.g., income or time), and during times of crisis, like with COVID-19, there may also be travel restrictions in place that prevent people from traveling to their preferred locations. Not all people have equal access to nature, including the kind of nature (mountains, desert, and so on) that they might enjoy most, and there are also differences in access within individual urban areas, where not everyone has equal access to recreational areas or parks. Thus, it is important for urban designers and researchers to understand which scenes of nature, whether photographs, murals on the sides of buildings, or some other form, people prefer and whether different scenes of nature can elicit different affective responses as well.

Figure 1: Three sets of six landscapes

Procedure

We used Survey Monkey to administer the survey and collect data. Participants were notified on the first page that participation was voluntary and that the participants could withdraw from the survey at any point without any repercussion. The procedures satisfied IRB protocols.

The survey had three parts: in the first part, the participants were shown each photograph individually in a randomized order and asked to rate each photograph on a Likert scale of 1 to 7, with 1 being Very Unattractive, 7 being Very Attractive, and 4 being a neutral response of Neither Attractive nor Unattractive.

The second part of the survey used the same 18 photographs, now in six groups of three photographs with each group composed of one of each kind (desert, mountain, hill) of photograph. The order of the type of scenery from left to right was randomized among the six groups. This second part of the survey asked participants to choose among the three photographs in each group for which photograph they would most like as the background image on their computer. This question was chosen to provide an active task of envisioned behavior—choosing an image for a specific purpose—in contract to the passive task of the appraisal of the attractiveness of the images. After each choice, the participant was asked to rate the photograph chosen based on the participant’s perception of how relaxing or exciting the place is; a Likert scale of 1 to 7 was once again used, this time with 1 being Very Relaxing, 7 being Very Exciting, and 4 being Neither Relaxing nor Exciting.

The third and final part of the survey asked for the participant’s gender, age, hometown (city and state if in the U.S.; city, state, and country if not in the U.S.), city or town in which the participant was currently living, and length of time having lived in the current location.

We used Survey Monkey to administer the survey and collect data. Participants were notified on the first page that participation was voluntary and that the participants could withdraw from the survey at any point without any repercussion. The procedures satisfied IRB protocols.

The survey had three parts: in the first part, the participants were shown each photograph individually in a randomized order and asked to rate each photograph on a Likert scale of 1 to 7, with 1 being Very Unattractive, 7 being Very Attractive, and 4 being a neutral response of Neither Attractive nor Unattractive.

The second part of the survey used the same 18 photographs, now in six groups of three photographs with each group composed of one of each kind (desert, mountain, hill) of photograph. The order of the type of scenery from left to right was randomized among the six groups. This second part of the survey asked participants to choose among the three photographs in each group for which photograph they would most like as the background image on their computer. This question was chosen to provide an active task of envisioned behavior—choosing an image for a specific purpose—in contract to the passive task of the appraisal of the attractiveness of the images. After each choice, the participant was asked to rate the photograph chosen based on the participant’s perception of how relaxing or exciting the place is; a Likert scale of 1 to 7 was once again used, this time with 1 being Very Relaxing, 7 being Very Exciting, and 4 being Neither Relaxing nor Exciting.

The third and final part of the survey asked for the participant’s gender, age, hometown (city and state if in the U.S.; city, state, and country if not in the U.S.), city or town in which the participant was currently living, and length of time having lived in the current location.

Results

In total, 227 people completed the survey. The mean age was 27.3 (SD 8.2 years) and more men (55%) than women (44%) participated. The majority (54%) of participants reported having lived in their region of the country for more than ten years, although the other time frames were also well-represented: less than one year (8.8%), between one and three years (16.7%), between three and five years (10.6%), and between five and ten years (9.7%).

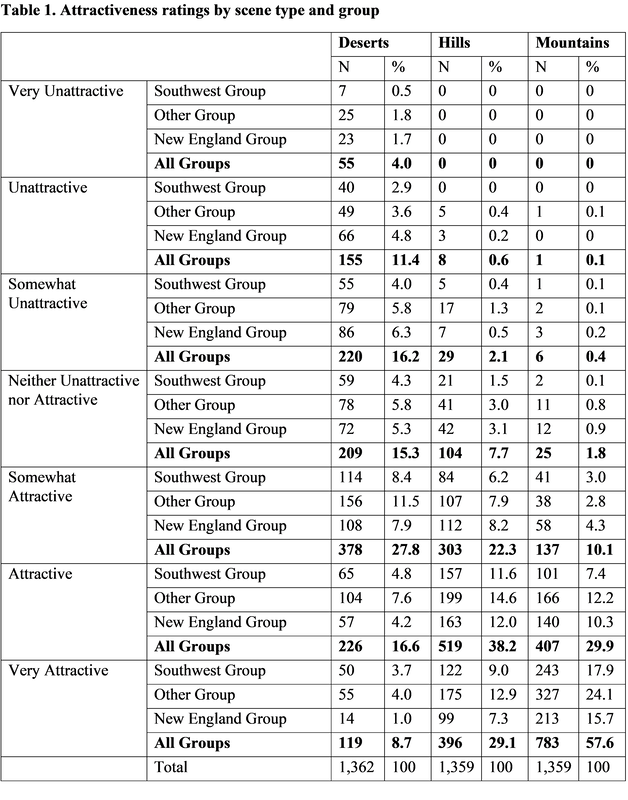

With 227 participants and six examples of each landscape type, each landscape type received up to 1,362 ratings (desert N = 1,362, hills N = 1,359, and mountains N = 1,359 ratings) (See Table 1). Overall, mountains received the highest average rating of attractiveness (mean of 6.42 on a scale of 1 to 7 with 7 being “Very Attractive,” SD = 0.78), followed by hills (mean of 5.83, SD = 0.95) and then deserts (mean of 4.36, SD = 1.47). The higher attractiveness ratings for mountains over deserts (d = 1.75, r = 0.66) and mountains over hills (d = 1.19, r = 0.51) represent large sized effects (Cohen 1988) while the higher attractiveness ratings for mountains over hills (d = 0.68, r = 0.32) is a moderate sized effect.

With 227 participants and six examples of each landscape type, each landscape type received up to 1,362 ratings (desert N = 1,362, hills N = 1,359, and mountains N = 1,359 ratings) (See Table 1). Overall, mountains received the highest average rating of attractiveness (mean of 6.42 on a scale of 1 to 7 with 7 being “Very Attractive,” SD = 0.78), followed by hills (mean of 5.83, SD = 0.95) and then deserts (mean of 4.36, SD = 1.47). The higher attractiveness ratings for mountains over deserts (d = 1.75, r = 0.66) and mountains over hills (d = 1.19, r = 0.51) represent large sized effects (Cohen 1988) while the higher attractiveness ratings for mountains over hills (d = 0.68, r = 0.32) is a moderate sized effect.

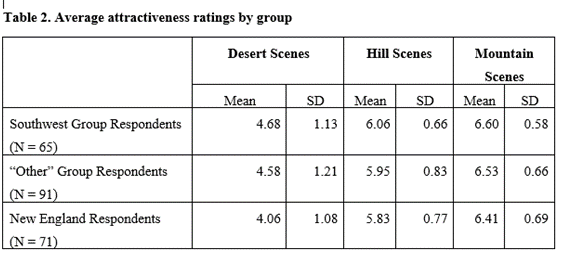

However, there were both similarities and differences in the ratings based on group. All three groups rated the mountain scenes, on average, as most attractive, the hill scenes as second-most attractive, and the desert scenes as the least attractive of the three types (see Table 2).

Participants from the Southwest group gave the highest overall ratings to each type of scene, and participants from the New England group gave the lowest overall ratings to each type of scenes. We ran regression analyses and found that Southwest and Other group participants’ ratings of the desert scenes were statistically significantly different than the New England group participants’ rating (F(2, 224) = 6.029, p = .003). With regard to the desert scenes, Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons found statistically significant differences between the Southwest and New England groups (F(136) = .621, p = .006), between the Other and New England groups (F(162) = .526, p = .013), but not between the Southwest and Other groups (F(156) = .095, p = 1.00). A majority (60%) of Southwest respondents as well as a majority (59.3%) of Other group respondents rated the desert scenes as Somewhat Attractive, Attractive, or Very Attractive; only 35.2% of the New England respondents gave the desert scenes one of these positive ratings.

There was no such statistically significant difference between the groups for either the mountain or hill scenes. Additionally, gender and length of residence had no statistically significant effect on participants’ attractiveness ratings of the scenes.

For the second part of the study, where the participants were asked to choose their most preferred computer background image among sets of scenes, with each set having one photograph from each type of scene, there was a strong preference overall for the mountain scenes. Among all participants, the mountain scenes were chosen 67.3%% of the time; the hill scenes were chosen 23% of the time, and the desert scenes were chosen only 9.7% of the time. However, participants from the three groups did not choose among the scenes equally, and the difference is statistically significant, X2 (2, N = 1,359) = 14.471, p = .006. Participants from the Southwest group and Other group were more likely to choose a desert image than participants from the New England group. This was a statistically significant difference (F(2, 224) = 3.180, p = .043). Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons found statistically significant differences between the Southwest and New England groups (F(136) = .389, p = .038), but not between the Other and New England groups (F(162) = .213, p = .411) or between the Southwest and Other groups (F(156) = .176, p = 0.694).

There was no statistically significant difference among the hill scenes (F(2, 224) = 1.413, p = .437), but there was an additional statistically significant difference among the mountain scenes (F(2, 224) = 6.936, p = .039). Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons found statistically significant differences between the New England and Southwest groups (F(136) = .607, p = .047), but not between the New England and Other groups (F(162) = .133, p = 1.00) or between the Other and Southwest groups (F(156) = .475, p = 0.136). Out of the 914 times a mountain scene was chosen, 375 times were by an Other group participant, 302 times by a New England participant, and 237 times by a Southwest participant.

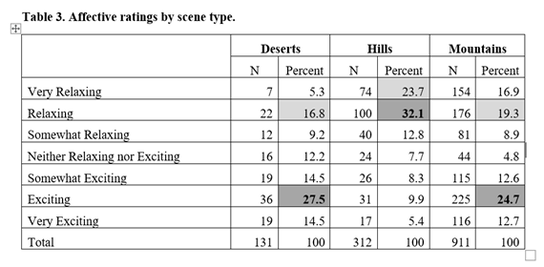

Furthermore, the affective reasons for scene selection varied by scene type and this was statistically significant, X2 (12, N = 1,354) = 95.132, p < .001 (see also Table 3). When hills were chosen as the preferred image for the background of a computer, the rating was more likely to be relaxing (Very Relaxing, Relaxing, or Somewhat Relaxing) rather than exciting (Very Exciting, Exciting, or Somewhat Exciting), with 68.6% of the responses rating the image as relaxing and 23.6% of the responses rating the image as exciting. Deserts were more likely to be seen as exciting (56.5% of ratings) rather than relaxing (31.3% of ratings). Mountains were almost as likely to be rated as relaxing (45.1% of the ratings) as exciting (50% of the ratings). There were no statistically significant differences in the affective ratings of the scenes between men and women or by length of residence. Additionally, although the group variable had a statistically significant relationship with the choice of scene type, as stated above, there was not a statistically significant relationship between the group variable and the affective rating of the scenes.

There was no such statistically significant difference between the groups for either the mountain or hill scenes. Additionally, gender and length of residence had no statistically significant effect on participants’ attractiveness ratings of the scenes.

For the second part of the study, where the participants were asked to choose their most preferred computer background image among sets of scenes, with each set having one photograph from each type of scene, there was a strong preference overall for the mountain scenes. Among all participants, the mountain scenes were chosen 67.3%% of the time; the hill scenes were chosen 23% of the time, and the desert scenes were chosen only 9.7% of the time. However, participants from the three groups did not choose among the scenes equally, and the difference is statistically significant, X2 (2, N = 1,359) = 14.471, p = .006. Participants from the Southwest group and Other group were more likely to choose a desert image than participants from the New England group. This was a statistically significant difference (F(2, 224) = 3.180, p = .043). Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons found statistically significant differences between the Southwest and New England groups (F(136) = .389, p = .038), but not between the Other and New England groups (F(162) = .213, p = .411) or between the Southwest and Other groups (F(156) = .176, p = 0.694).

There was no statistically significant difference among the hill scenes (F(2, 224) = 1.413, p = .437), but there was an additional statistically significant difference among the mountain scenes (F(2, 224) = 6.936, p = .039). Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons found statistically significant differences between the New England and Southwest groups (F(136) = .607, p = .047), but not between the New England and Other groups (F(162) = .133, p = 1.00) or between the Other and Southwest groups (F(156) = .475, p = 0.136). Out of the 914 times a mountain scene was chosen, 375 times were by an Other group participant, 302 times by a New England participant, and 237 times by a Southwest participant.

Furthermore, the affective reasons for scene selection varied by scene type and this was statistically significant, X2 (12, N = 1,354) = 95.132, p < .001 (see also Table 3). When hills were chosen as the preferred image for the background of a computer, the rating was more likely to be relaxing (Very Relaxing, Relaxing, or Somewhat Relaxing) rather than exciting (Very Exciting, Exciting, or Somewhat Exciting), with 68.6% of the responses rating the image as relaxing and 23.6% of the responses rating the image as exciting. Deserts were more likely to be seen as exciting (56.5% of ratings) rather than relaxing (31.3% of ratings). Mountains were almost as likely to be rated as relaxing (45.1% of the ratings) as exciting (50% of the ratings). There were no statistically significant differences in the affective ratings of the scenes between men and women or by length of residence. Additionally, although the group variable had a statistically significant relationship with the choice of scene type, as stated above, there was not a statistically significant relationship between the group variable and the affective rating of the scenes.

Conclusion

Overall, there was agreement among the three groups of students that the hill scenes were much more likely to be regarded as relaxing than exciting, the desert scenes were somewhat more likely to be rated as exciting than relaxing, and the mountain scenes were sometimes seen as relaxing and sometimes as exciting. This may have important implications for individuals who are seeking to alter their mood, whether it is to aid in feeling calm or to view an exciting image when depressed. It could be that one reason for the few picks of a desert as the scene of choice for a computer background image is that respondents desire a relaxing image more often than they desire an exciting image. Alternately, it could be that respondents in New England are less familiar with desert scenes and find those images less appealing. Nevertheless, this study did not ask respondents for their reasons in choosing the images that they preferred for a computer background image, and thus we can only speculate. Furthermore, this study did not assess whether there was a relationship between affective appraisal of scenes and mood induction, and simply because a respondent chose an image that he or she judged to be relaxing does not mean that the image had a relaxing effect on the respondent.

Familiarity with certain kinds of scenery may help people to feel more positively about it and, in some cases, even prefer it. In this study, respondents from the Southwest viewed desert landscaping as more attractive than respondents from New England did. However, the reverse is not true; respondents from the New England group did not rate the hills scenes more positively than the other groups. Rather, the Southwest group respondents gave the highest ratings to all three types of landscaping and the New England group gave the lowest ratings to all three types of groups. We cannot account for why the stimuli elicited less of an emotional response from the New England group respondents than from the other groups. Future studies may seek a more diverse sample – as New England in itself has a diversity of landscapes from mountains, forests, hills, and coastline. Our participants from New England were from hilly home environments, but New Englanders from other home environments might provide different ratings.

We also did not assess the extent to which the respondents have traveled, and travel experience could affect familiarity with various landscapes. Furthermore, travel could indicate an affinity for certain kinds of landscapes, such as landscapes that are seen as exotic or different from where one lives.

The affective ratings of the scenery types did not vary by group, gender, age, or length of residence. We expected to find, throughout the study, that length of residence would matter and that respondents who were new to a region may rate the scenery types differently than those respondents who were lifelong residents of that region. A future study may indeed find this to be the case with a larger sample, but it was insignificant in our study.

We were particularly interested in students’ responses to nature scenes because university students are a vulnerable group for mental health struggles. With Covid-19 and other future crises, viewing scenes of nature may be a coping mechanism to provide stress relief. Future studies may wish to add a physiological component to assess whether viewing nature scenes has a measurable effect on stress hormones. Additionally, it would be useful to extend the study to non-student populations and non-U.S.-based populations as well.

Lastly, we did not account for personal preferences for nature versus urbanity, or strength of feeling toward various landscapes because we chose to focus on geographic familiarity. It could be that some of the respondents have preferences about types of nature or, in fact, prefer scenes of city life to scenes of nature, in ways that could be relevant to our study. A future study should assess these preferences.

Familiarity with certain kinds of scenery may help people to feel more positively about it and, in some cases, even prefer it. In this study, respondents from the Southwest viewed desert landscaping as more attractive than respondents from New England did. However, the reverse is not true; respondents from the New England group did not rate the hills scenes more positively than the other groups. Rather, the Southwest group respondents gave the highest ratings to all three types of landscaping and the New England group gave the lowest ratings to all three types of groups. We cannot account for why the stimuli elicited less of an emotional response from the New England group respondents than from the other groups. Future studies may seek a more diverse sample – as New England in itself has a diversity of landscapes from mountains, forests, hills, and coastline. Our participants from New England were from hilly home environments, but New Englanders from other home environments might provide different ratings.

We also did not assess the extent to which the respondents have traveled, and travel experience could affect familiarity with various landscapes. Furthermore, travel could indicate an affinity for certain kinds of landscapes, such as landscapes that are seen as exotic or different from where one lives.

The affective ratings of the scenery types did not vary by group, gender, age, or length of residence. We expected to find, throughout the study, that length of residence would matter and that respondents who were new to a region may rate the scenery types differently than those respondents who were lifelong residents of that region. A future study may indeed find this to be the case with a larger sample, but it was insignificant in our study.

We were particularly interested in students’ responses to nature scenes because university students are a vulnerable group for mental health struggles. With Covid-19 and other future crises, viewing scenes of nature may be a coping mechanism to provide stress relief. Future studies may wish to add a physiological component to assess whether viewing nature scenes has a measurable effect on stress hormones. Additionally, it would be useful to extend the study to non-student populations and non-U.S.-based populations as well.

Lastly, we did not account for personal preferences for nature versus urbanity, or strength of feeling toward various landscapes because we chose to focus on geographic familiarity. It could be that some of the respondents have preferences about types of nature or, in fact, prefer scenes of city life to scenes of nature, in ways that could be relevant to our study. A future study should assess these preferences.

About the Authors

|

Kathryn Terzano, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Community and Regional Planning at Iowa State University, USA, whose teaching and research interests center on environmental psychology and urban design. Contact her via LinkedIn.

|

|

Alina T. Gross, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Geography and Regional Planning at Westfield State University, USA. Her teaching, research, and professional planning work focuses on housing, public participation, and community-based planning. Contact her via LinkedIn.

|

References

Balling, J. D., & Falk, J. H. (1982). Development of visual preference for natural environments. Environment and Behavior, 14, 5–28.

Bell, Sarah L, Cassandra Phoenix, Rebecca Lovell, and Benedict W Wheeler. 2015. "Seeking everyday wellbeing: The coast as a therapeutic landscape." Social Science & Medicine 142: 56-67.

Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Fuller, Richard A, Katherine N Irvine, Patrick Devine-Wright, Philip H Warren, and Kevin J Gaston. 2007. "Physcological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity." Biology Letter 3 (4).

Hagerhall , Caroline M. , Terry Purcell, and Richard Taylor. 2004. "Fractal dimension of landscape silhouette outlines as a predictor of landscape preference." Journal of Environmental Pschology 24 (2): 247-255.

Herzog, Thomas R, Stephen Kaplan , and Rachel Kaplan. 1982. "The Prediction of Preference For Unfamiliar Urban Places." Population and Environment 5 (1).

Joye, Yannick, and Agnes van de Berg. 2011. "Is love for green in our genes? A critical analysis of evolutionary assumptions in restorative environments research." Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 10 (4): 261-268.

Kals, Elisabeth, Daniel Schumacher, and Leo Montada. 1999. "Emotional Affinity toward Nature as a Motivational Basis to Protect Nature ." Environment and Behavior 31 (2): 178-202.

Kaplan , Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan . 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kaplan , Stephen, Rachel Kaplan, and John S Wendt. 1972. "Rated Preference and Complexity for Natural and Urban Visual Material." Perception & Psychophysics 12 (4): 354-356.

Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. 1989. The Experinece of Nature: A Psychological Perspecitive. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

Kaplan, Stephen. 1987. "Aestheics, Affect, Cognition." Environment and Behavior 19 (1).

Karl, Dake. 1992. "Myths of Nature: Culture and the Social Construction of Risk." Journal of Social Issues 48 (4): 21-37.

Lamb, R J, and A T Purcell. 1990. "Perception of Naturalness in Landscape and its Relationship to Vegetaion Structure ." Landscape and Urban Planning 19 (4): 333-352.

Leila , Scannell, and Robert Gifford. 2011. "Personally Relevant Climate Change: The Role of Place Attachment and Local Versus Global Message Framing in Engagement." Environment and Behavior 45 (1).

Lo, Alex, and C.Y. Jim. 2015. "Community attachment and resident attitude toward old masonry walls and associated trees in urban Hong Kong." Cities 42 (A): 130-141.

Mayer, F. Stephan, and Cynthia McPherson Frantz. 2004. "The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature." Journal of Environmental Psychology 24 (4): 503-515.

Medidenbauer, Kimberly L, Cecilia U.D. Stenfors, Jaime Young, Elliot A Layden, Kathryn E Schertz, Omid Kardan, Jean Decety, and Marc G Berman. 2019. "The gradual development of the preference for natural elements." Journal of Environmental Psychology 65.

Meredith, G. R., D. A. Rakow, E. Eldermire, C. G. Madsen, S. P. Shelley, and N. A. Sachs. 2020. "Minimum Time Dose in Nature to Positively Impact the Mental Health of College-Aged Students, and How to Measure It: A Scoping Review." Frontiers in Psychology.

Mohamed, E.L. Sadek, Hyunjo Jo, Minkai Sun, and Eijiro Fujii. 2013. "Brain activity and Emotional Responses of the Japanese People Toward Trees Pruned using Sukashi Technique." International Journal of Agriculture, Environment & Biotechnology 6 (3): 344-350.

Nasar, Jack L. 1994. "Urban Design Aesthetics: The Evaluative Qualities of Building Exteriors." Environment and Behavior 26 (3).

Nutsford, Daniel, Amber L Pearson, Simon Kingham, and Femke Reitsma. 2016. " Residential exposure to visible blue space (but not green space) associated with lower psychological distress in a capital city." Health Place 39: 70-78.

Perrin, Jeffrey L., and Victor A. Benassi. 2009. "The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of emotional connection to nature?" Journal of Environmental Psychology 29 (4): 434-440.

Robbins, Paul, John Hintz, and Sarah A Moore. 2014. Environment and Society: A Critical Introduction. Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.

Scannell, Leila, and Robert Gifford. 2011. "Personally Relevant Cliamte Change: The Role of Place Attachment and Local Versus Global Message Framing in Engagement." Environment and Behavior 45 (1).

Sheets, Virgil L. , and Chris D. Manzer. 1991. "Affect, Cognition, and Urban Vegetation: Some Effects of Adding Trees Along City Streets." Environment and Behavior 23 (2): 285-304.

Ulrich, R. S. 1984. "View through a window may influence recovery from surgery." Science 420-421.

Ulrich, Roger S. 1986. "Human Responses to Vegetation and Landscapes ." Landscape and Urban Planning 13: 29-44.

Walker, Amanda J, and Robert L Ryan. 2008. "Place attachment and landscape preservation in rural New England: A Maine case study." Landscape and Urban Planning 86 (2): 141-152.

Wang, Ke, Qingming Cui, and Honggang Xu. 2018. "Desert as therapeutic space: Cultural interpretation of embodied experience in sand therapy in Xinjiang, China." Health & Place 53: 173-181.

Bell, Sarah L, Cassandra Phoenix, Rebecca Lovell, and Benedict W Wheeler. 2015. "Seeking everyday wellbeing: The coast as a therapeutic landscape." Social Science & Medicine 142: 56-67.

Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Fuller, Richard A, Katherine N Irvine, Patrick Devine-Wright, Philip H Warren, and Kevin J Gaston. 2007. "Physcological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity." Biology Letter 3 (4).

Hagerhall , Caroline M. , Terry Purcell, and Richard Taylor. 2004. "Fractal dimension of landscape silhouette outlines as a predictor of landscape preference." Journal of Environmental Pschology 24 (2): 247-255.

Herzog, Thomas R, Stephen Kaplan , and Rachel Kaplan. 1982. "The Prediction of Preference For Unfamiliar Urban Places." Population and Environment 5 (1).

Joye, Yannick, and Agnes van de Berg. 2011. "Is love for green in our genes? A critical analysis of evolutionary assumptions in restorative environments research." Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 10 (4): 261-268.

Kals, Elisabeth, Daniel Schumacher, and Leo Montada. 1999. "Emotional Affinity toward Nature as a Motivational Basis to Protect Nature ." Environment and Behavior 31 (2): 178-202.

Kaplan , Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan . 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kaplan , Stephen, Rachel Kaplan, and John S Wendt. 1972. "Rated Preference and Complexity for Natural and Urban Visual Material." Perception & Psychophysics 12 (4): 354-356.

Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. 1989. The Experinece of Nature: A Psychological Perspecitive. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

Kaplan, Stephen. 1987. "Aestheics, Affect, Cognition." Environment and Behavior 19 (1).

Karl, Dake. 1992. "Myths of Nature: Culture and the Social Construction of Risk." Journal of Social Issues 48 (4): 21-37.

Lamb, R J, and A T Purcell. 1990. "Perception of Naturalness in Landscape and its Relationship to Vegetaion Structure ." Landscape and Urban Planning 19 (4): 333-352.

Leila , Scannell, and Robert Gifford. 2011. "Personally Relevant Climate Change: The Role of Place Attachment and Local Versus Global Message Framing in Engagement." Environment and Behavior 45 (1).

Lo, Alex, and C.Y. Jim. 2015. "Community attachment and resident attitude toward old masonry walls and associated trees in urban Hong Kong." Cities 42 (A): 130-141.

Mayer, F. Stephan, and Cynthia McPherson Frantz. 2004. "The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature." Journal of Environmental Psychology 24 (4): 503-515.

Medidenbauer, Kimberly L, Cecilia U.D. Stenfors, Jaime Young, Elliot A Layden, Kathryn E Schertz, Omid Kardan, Jean Decety, and Marc G Berman. 2019. "The gradual development of the preference for natural elements." Journal of Environmental Psychology 65.

Meredith, G. R., D. A. Rakow, E. Eldermire, C. G. Madsen, S. P. Shelley, and N. A. Sachs. 2020. "Minimum Time Dose in Nature to Positively Impact the Mental Health of College-Aged Students, and How to Measure It: A Scoping Review." Frontiers in Psychology.

Mohamed, E.L. Sadek, Hyunjo Jo, Minkai Sun, and Eijiro Fujii. 2013. "Brain activity and Emotional Responses of the Japanese People Toward Trees Pruned using Sukashi Technique." International Journal of Agriculture, Environment & Biotechnology 6 (3): 344-350.

Nasar, Jack L. 1994. "Urban Design Aesthetics: The Evaluative Qualities of Building Exteriors." Environment and Behavior 26 (3).

Nutsford, Daniel, Amber L Pearson, Simon Kingham, and Femke Reitsma. 2016. " Residential exposure to visible blue space (but not green space) associated with lower psychological distress in a capital city." Health Place 39: 70-78.

Perrin, Jeffrey L., and Victor A. Benassi. 2009. "The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of emotional connection to nature?" Journal of Environmental Psychology 29 (4): 434-440.

Robbins, Paul, John Hintz, and Sarah A Moore. 2014. Environment and Society: A Critical Introduction. Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.

Scannell, Leila, and Robert Gifford. 2011. "Personally Relevant Cliamte Change: The Role of Place Attachment and Local Versus Global Message Framing in Engagement." Environment and Behavior 45 (1).

Sheets, Virgil L. , and Chris D. Manzer. 1991. "Affect, Cognition, and Urban Vegetation: Some Effects of Adding Trees Along City Streets." Environment and Behavior 23 (2): 285-304.

Ulrich, R. S. 1984. "View through a window may influence recovery from surgery." Science 420-421.

Ulrich, Roger S. 1986. "Human Responses to Vegetation and Landscapes ." Landscape and Urban Planning 13: 29-44.

Walker, Amanda J, and Robert L Ryan. 2008. "Place attachment and landscape preservation in rural New England: A Maine case study." Landscape and Urban Planning 86 (2): 141-152.

Wang, Ke, Qingming Cui, and Honggang Xu. 2018. "Desert as therapeutic space: Cultural interpretation of embodied experience in sand therapy in Xinjiang, China." Health & Place 53: 173-181.