|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2020:6;10 (Advance publication 2019)

|

Urban design and mental health in George Town, Malaysia: a city case study

Uta Dietrich (1), Jean Chu (2), Yeoh Hui Li (1), Aish Kumar (1)

(1) Think City, Malaysia

(2) Ipsos

(1) Think City, Malaysia

(2) Ipsos

Abstract - Summary

One in three people reported mental health issues in a national survey in Malaysia, a country with an urbanisation rate of over 75%. Urban design has great potential to improve mental wellbeing as a growing body of evidence shows. This study of the tropical city of George Town interviewed professionals from architecture and planning as well as health and consumer advocates to find out their view on seven established factors linking urban design to mental health and to identify any specific features affecting the mental health of residents in George Town in a positive or negative way. Two additional issues were identified. While restoration and preservation of heritage building provides a sense of pride, belonging and income, it can also be a major cause of stress, particularly in the UNESCO heritage zone due to congestion and for residents, who feel they lose their privacy as visitors look into or even try to enter their homes. The second issue is about urban heat as a factor that stops people walking outside; reducing exercise and access to nature.

Introduction

Research on the connection between urban design and health is not new but has gained renewed interest in recent years as the world continues to urbanise with design that contributes to ill-health. However less focus has been given to the link between mental health and urban design. While the research evidence is growing, there is still very little awareness among various professional groups and the general public.

Mental health is not the same as mental illness. According to the World Health Organisation, mental health is defined as: “a state of well-being in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.” The key principles of urban design for good population health mental health outline opportunities for cities to support individuals and communities to build their resilience and mental-wellbeing. This case study reflects how these principles apply to George Town, Penang and identifies opportunities for improvement.

The key principles of urban design that affects mental health used in this case study are:

Overview of mental health in George Town

As in other countries, the available mental health statistics are actually those of mental illness. Prevalence of mental health problems, according to the National Health and Morbidity Survey (2015), was 29.2% across Malaysia (CI 27.9-30.5) and significantly less for Penang at 19.1% (CI 14.6-24.7). Yeoh et al. (2017) identified lower rates of depression in ethnic Chinese, the largest ethnic group in Penang; making this a potential contributing factor. Among adolescents aged 14-17 years old, 6% had self-reported suicides attempts - not significantly different to the overall rate for Malaysia of 6.9% according to the NHMS Adolescent Health Survey 2017. According to WHO, among all ages, the suicide death rate across Malaysia was 6.2 per 100,000 population in 2016, lower than its neighbouring countries Thailand (12.9/100,000) and Singapore (7.9/100,000).

It must also be noted that almost 20 years earlier in 1996, the Malaysian prevalence rate for mental health problems was recorded as only 10.7%. Whether these increases are linked to increased development, higher urbanisation or just more open reporting is difficult to say.

A detailed review of the mental health care system by the Penang Institute in 2017 further identified that low-income earners, the unemployed, young people aged 16-24, and women were at highest risk. The report summarises that the key challenges around mental health and its care are the shortage of trained professionals in psychiatry and psychology, cost of treatment of having to access private sector care and lack of coverage by health insurance.

The history of health care in this region, including some psychiatric care in Penang, has been documented since its beginning; historical documents represent its struggles with the treatment of opium addiction for almost 200 years to the mid-20th century. Today, WHO recommends a ratio of 1 psychiatrist for every 10,000 people; Malaysia has 1.27 Psychiatrists per 100,000 population. A 2018 study identified that Malaysia had only 410 registered psychiatrists, and these were working mainly in government hospitals and concentrated in Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya. This makes it more urgent to create an environment that encourages good mental health.

Views on mental illness are strongly influenced by religion and ethnic beliefs. As Malaysia is very ethnically diverse, so are the views on the causes of mental health problems, ranging from the biomedical to supernatural explanations, such as spirit attacks and black magic. It can be said that people with mental health issues are often viewed as having a negative character trait, lacking morals or religious conviction and mental illness is generally perceived as a personal weakness. Not being able to cope is often viewed as social disgrace. This stigma leads to discrimination in the workplace, and reduces help-seeking behaviour.

While there is some discussion and concern about mental health issues in the media, there is not yet a public discourse on mental health promotion and prevention at population level.

Urban planning and design in George Town

George Town is the capital of the State of Penang and is located on the island of Penang in Malaysia. George Town has a population of around 700,000 people and is a UNESCO world heritage site attracting a rising numbers of tourists looking to experience the local food and historic buildings. Between 2006 and 2016, hotel guest numbers increased from 4.3 to 6.4 million including local and international tourists, and cruise ship arrivals have grown to an additional 1 million visitors per year (p.71). While the economy benefits from this influx of visitors, residents in the heritage core also report of added traffic congestion and of people looking into their homes as if they were museums.

George Town began as a settlement established by the British East India Company in 1786 before becoming a British Colony along with Malacca and Singapore, known as the Straits Settlement. Established as a free port, George Town prospered in the 19th century partly based on a flourishing opium trade. Its buildings and architecture reflected the international and multi-ethnic influences of a port city. During World War II, Penang was occupied by the Japanese Empire (1941-45). After the war it became part of the Federation of Malaya and after Independence in 1957 part of Malaysia. Just before Independence, George Town received city status by the British Monarch and is now the second largest conurbation in Malaysia with almost 1.8 million residents including surrounding towns. Since George Town received the UNESCO World Heritage Status for its dense, rich accumulation of heritage buildings in 2008, over 500 dilapidated buildings have been restored, leading to a flourishing tourism industry and increasing numbers of visitors (see above).

Since independence, Malaysia has been a Federation of States and Territories governed as a representative democratic constitutional monarchy. Local government, in this context, is seen as an extension of the state, with mayors and councilors appointed rather than elected. The physical planning system in Malaysia is multi-tiered. The overarching national framework is the National Physical Plan (NPP) and the current one focuses on building a liveable and resilient nation with balanced urban growth, integrated rural developments and improved connectivity. Holistic planning and low carbon cities also feature. The NPP guides state level Structure Plans which in turn guide the preparation of Local Plans at the municipal level, which provide more detailed urban development guidelines. Unique areas, such as heritage sites, can be subject to more stringent and detailed “special area plans”. While on paper Malaysia’s planning system looks robust, there is development that occurs at odds with policy settings.

The Malaysian Town and Country Planning Act 1976 (Act 172) was complemented in 1995 by the Town Planners Act (Act 538) and these Acts regulate the planning profession. On the ground, the Malaysian Standard MS1141 guiding universal design and the Special Area Plans will indirectly benefit mental health even though health is not an explicit focus. Most recently, the Penang 2030: Democratising Policy Making is setting the strategy direction for the state of Penang to improve liveability, increase household incomes, improve participation and reduce inequities as well as investing in the built environment to raise resilience, all factors linked to improved mental health.

Mental health is not the same as mental illness. According to the World Health Organisation, mental health is defined as: “a state of well-being in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.” The key principles of urban design for good population health mental health outline opportunities for cities to support individuals and communities to build their resilience and mental-wellbeing. This case study reflects how these principles apply to George Town, Penang and identifies opportunities for improvement.

The key principles of urban design that affects mental health used in this case study are:

- Green space and access to nature

- Active space for exercise

- Pro-social places to encourage positive social interaction

- Safety in the city

- Sleep (avoid noise and light pollution)

- Economic stress and affordability in the city

- Air pollution

Overview of mental health in George Town

As in other countries, the available mental health statistics are actually those of mental illness. Prevalence of mental health problems, according to the National Health and Morbidity Survey (2015), was 29.2% across Malaysia (CI 27.9-30.5) and significantly less for Penang at 19.1% (CI 14.6-24.7). Yeoh et al. (2017) identified lower rates of depression in ethnic Chinese, the largest ethnic group in Penang; making this a potential contributing factor. Among adolescents aged 14-17 years old, 6% had self-reported suicides attempts - not significantly different to the overall rate for Malaysia of 6.9% according to the NHMS Adolescent Health Survey 2017. According to WHO, among all ages, the suicide death rate across Malaysia was 6.2 per 100,000 population in 2016, lower than its neighbouring countries Thailand (12.9/100,000) and Singapore (7.9/100,000).

It must also be noted that almost 20 years earlier in 1996, the Malaysian prevalence rate for mental health problems was recorded as only 10.7%. Whether these increases are linked to increased development, higher urbanisation or just more open reporting is difficult to say.

A detailed review of the mental health care system by the Penang Institute in 2017 further identified that low-income earners, the unemployed, young people aged 16-24, and women were at highest risk. The report summarises that the key challenges around mental health and its care are the shortage of trained professionals in psychiatry and psychology, cost of treatment of having to access private sector care and lack of coverage by health insurance.

The history of health care in this region, including some psychiatric care in Penang, has been documented since its beginning; historical documents represent its struggles with the treatment of opium addiction for almost 200 years to the mid-20th century. Today, WHO recommends a ratio of 1 psychiatrist for every 10,000 people; Malaysia has 1.27 Psychiatrists per 100,000 population. A 2018 study identified that Malaysia had only 410 registered psychiatrists, and these were working mainly in government hospitals and concentrated in Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya. This makes it more urgent to create an environment that encourages good mental health.

Views on mental illness are strongly influenced by religion and ethnic beliefs. As Malaysia is very ethnically diverse, so are the views on the causes of mental health problems, ranging from the biomedical to supernatural explanations, such as spirit attacks and black magic. It can be said that people with mental health issues are often viewed as having a negative character trait, lacking morals or religious conviction and mental illness is generally perceived as a personal weakness. Not being able to cope is often viewed as social disgrace. This stigma leads to discrimination in the workplace, and reduces help-seeking behaviour.

While there is some discussion and concern about mental health issues in the media, there is not yet a public discourse on mental health promotion and prevention at population level.

Urban planning and design in George Town

George Town is the capital of the State of Penang and is located on the island of Penang in Malaysia. George Town has a population of around 700,000 people and is a UNESCO world heritage site attracting a rising numbers of tourists looking to experience the local food and historic buildings. Between 2006 and 2016, hotel guest numbers increased from 4.3 to 6.4 million including local and international tourists, and cruise ship arrivals have grown to an additional 1 million visitors per year (p.71). While the economy benefits from this influx of visitors, residents in the heritage core also report of added traffic congestion and of people looking into their homes as if they were museums.

George Town began as a settlement established by the British East India Company in 1786 before becoming a British Colony along with Malacca and Singapore, known as the Straits Settlement. Established as a free port, George Town prospered in the 19th century partly based on a flourishing opium trade. Its buildings and architecture reflected the international and multi-ethnic influences of a port city. During World War II, Penang was occupied by the Japanese Empire (1941-45). After the war it became part of the Federation of Malaya and after Independence in 1957 part of Malaysia. Just before Independence, George Town received city status by the British Monarch and is now the second largest conurbation in Malaysia with almost 1.8 million residents including surrounding towns. Since George Town received the UNESCO World Heritage Status for its dense, rich accumulation of heritage buildings in 2008, over 500 dilapidated buildings have been restored, leading to a flourishing tourism industry and increasing numbers of visitors (see above).

Since independence, Malaysia has been a Federation of States and Territories governed as a representative democratic constitutional monarchy. Local government, in this context, is seen as an extension of the state, with mayors and councilors appointed rather than elected. The physical planning system in Malaysia is multi-tiered. The overarching national framework is the National Physical Plan (NPP) and the current one focuses on building a liveable and resilient nation with balanced urban growth, integrated rural developments and improved connectivity. Holistic planning and low carbon cities also feature. The NPP guides state level Structure Plans which in turn guide the preparation of Local Plans at the municipal level, which provide more detailed urban development guidelines. Unique areas, such as heritage sites, can be subject to more stringent and detailed “special area plans”. While on paper Malaysia’s planning system looks robust, there is development that occurs at odds with policy settings.

The Malaysian Town and Country Planning Act 1976 (Act 172) was complemented in 1995 by the Town Planners Act (Act 538) and these Acts regulate the planning profession. On the ground, the Malaysian Standard MS1141 guiding universal design and the Special Area Plans will indirectly benefit mental health even though health is not an explicit focus. Most recently, the Penang 2030: Democratising Policy Making is setting the strategy direction for the state of Penang to improve liveability, increase household incomes, improve participation and reduce inequities as well as investing in the built environment to raise resilience, all factors linked to improved mental health.

Methods

Eleven urban planners, architects, academics, mental health professionals, public health officers, a civil society activist and a consumer representative operating in George Town or the wider Penang Island were interviewed using snowball sampling. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with each person. Each subject was asked about urban design factors that support good mental health, relevant policies and plans and any barriers to prioritisation following a set protocol. Interview responses were then grouped into three groups: 1. Architect/Planner 2. Health Professionals and 3. Consumer Advocates. The groups represent professionals as well as academics.

Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Information was then sorted by the three professional groups mentioned above and each of the eight recognised links between urban design and mental health. Not all eight themes were mentioned by interviews so that the results only reflect those discussed during interviews. Other emerging themes were noted and considered by the authors for inclusion.

Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Information was then sorted by the three professional groups mentioned above and each of the eight recognised links between urban design and mental health. Not all eight themes were mentioned by interviews so that the results only reflect those discussed during interviews. Other emerging themes were noted and considered by the authors for inclusion.

Results

These results describe the built environment factors that respondents believed can impact mental health in George Town, Penang.

Perceived priority level of urban design for mental health in George Town

The link between urban design and mental health was generally acknowledged. Consumer advocates, architects and planners were all aware of the linkages and considered them in their practice. Thinking among health professionals was not as uniform. In terms of regulation, social planning guidelines were considered the platform bringing wellbeing and planning together but it was acknowledged that stronger consideration for health including mental health were needed in planning and design guidelines and their implementation.

“The look of a city affects mental health. It is important that George Town retains its unique aesthetic amid growing concern of the Penang’s new high-rise developments. People-centric designs are also imperative to discussion of urban-induced mental health issues. Government incentives to incorporate mental health indices in policy remain non-existent, and poor functionality of existing infrastructure leads to stress amongst residents.” (Architect)

“Few people would consciously look at creating mental-health friendly environments." (Planner)

“Urban design should recognise the positive impact of soothing environment in body and mind.” (Consumer Advocate)

Health professionals were not aware of any health guidelines or regulation sconsidering urban design. More interaction between disciplines would benefit urban design for the wellbeing of residents.

George Town has probably Malaysia’s strongest consumer movement, which started in Penang. Insights from consumer advocates/activists provides another facet on how the link between mental health and urban design is viewed.

The analysis is based on two interviews. Their general view was that every aspect of design, whether inside or outside, height, views, materials should be viewed as one. The interaction between all components influenced people’s feelings and emotions. One advocate recommended that urban design should focus on connectivity and linkages, built and natural environment, considering its impact on mood, spirituality and learning. He encouraged the engagement of civil society in planning and creating public spaces so that all would benefit, and the people’s perspective included.

“Improved urban design guidelines and incentives for developers to implement social planning should be looked into. The transparency of roles between government organisations should be publicly available as well. As it stands, political goals aim to meet short-term goals without a considering of long-term impacts and consequences of imposed solutions.” (Architect)

“Legislation has unrealistic requirements that are not necessary. Legislation must facilitate, not hinder.” (Health Professional)

“Planners do not discuss with academics. Policy makers do not engage academics. A huge untapped resource and huge shame.” (Health Professional)

“Policy makers think about today not about tomorrow.” (Health Professional)

“Council has public health doctors, but they are not involved in town planning; more in infectious disease control.” (Health Professional)

Perceived priority level of urban design for mental health in George Town

The link between urban design and mental health was generally acknowledged. Consumer advocates, architects and planners were all aware of the linkages and considered them in their practice. Thinking among health professionals was not as uniform. In terms of regulation, social planning guidelines were considered the platform bringing wellbeing and planning together but it was acknowledged that stronger consideration for health including mental health were needed in planning and design guidelines and their implementation.

“The look of a city affects mental health. It is important that George Town retains its unique aesthetic amid growing concern of the Penang’s new high-rise developments. People-centric designs are also imperative to discussion of urban-induced mental health issues. Government incentives to incorporate mental health indices in policy remain non-existent, and poor functionality of existing infrastructure leads to stress amongst residents.” (Architect)

“Few people would consciously look at creating mental-health friendly environments." (Planner)

“Urban design should recognise the positive impact of soothing environment in body and mind.” (Consumer Advocate)

Health professionals were not aware of any health guidelines or regulation sconsidering urban design. More interaction between disciplines would benefit urban design for the wellbeing of residents.

George Town has probably Malaysia’s strongest consumer movement, which started in Penang. Insights from consumer advocates/activists provides another facet on how the link between mental health and urban design is viewed.

The analysis is based on two interviews. Their general view was that every aspect of design, whether inside or outside, height, views, materials should be viewed as one. The interaction between all components influenced people’s feelings and emotions. One advocate recommended that urban design should focus on connectivity and linkages, built and natural environment, considering its impact on mood, spirituality and learning. He encouraged the engagement of civil society in planning and creating public spaces so that all would benefit, and the people’s perspective included.

“Improved urban design guidelines and incentives for developers to implement social planning should be looked into. The transparency of roles between government organisations should be publicly available as well. As it stands, political goals aim to meet short-term goals without a considering of long-term impacts and consequences of imposed solutions.” (Architect)

“Legislation has unrealistic requirements that are not necessary. Legislation must facilitate, not hinder.” (Health Professional)

“Planners do not discuss with academics. Policy makers do not engage academics. A huge untapped resource and huge shame.” (Health Professional)

“Policy makers think about today not about tomorrow.” (Health Professional)

“Council has public health doctors, but they are not involved in town planning; more in infectious disease control.” (Health Professional)

Blue and green space and access to nature

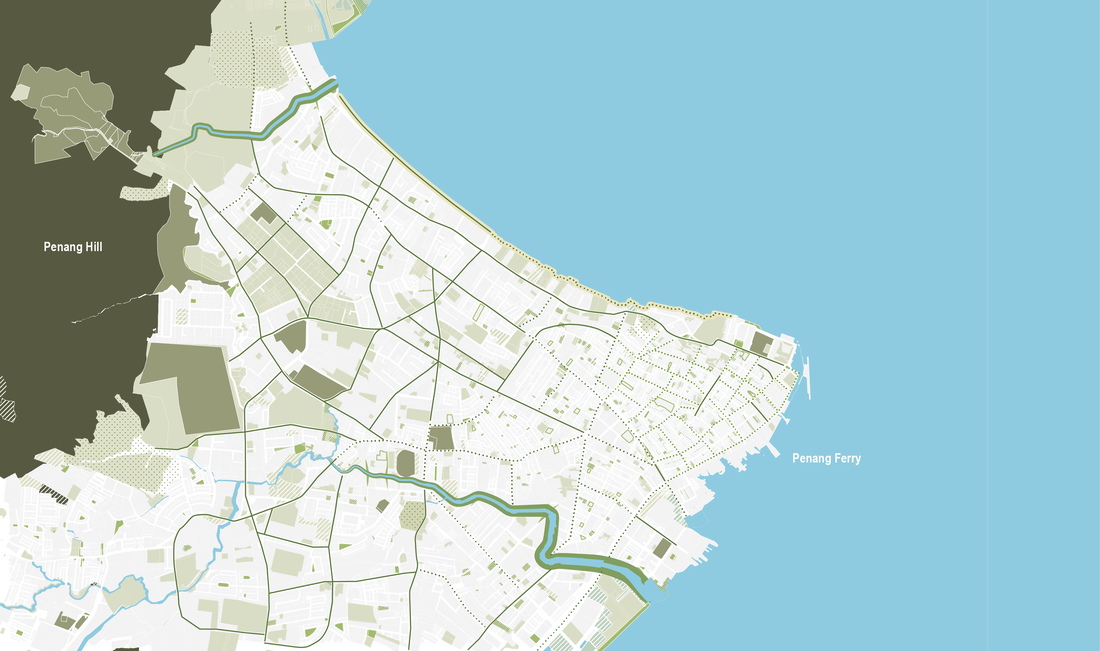

George Town’s location between the sea and rainforest-covered hills on Penang Island’s centre was noted by many interviewees as its greatest asset in terms of mental health.

Water

George Town is surrounded by the sea on two sides and has a few rivers. Interviewees reported the calming and de-stressing effect of being able to look at flowing water and hearing it.

“Being able feel the breeze of the see while being able to see the forest provides for a sense of calmness”. (Health Professional)

“Walking along a river can be very calming.” (Health Professional)

“Water views and sound are calming” (Health Professional)

“One other significant stories of design in Penang is shape. The shape of the Penang island is like a piece of cake, both sides of the cake are facing the sea. This creates a certain amount of openness and character, with the breeze and sights, makes you fall in love with the place. The joy of seeing the hill (still highly forested), at the middle of the ‘cake’, is highly spectacular.” (Consumer Advocate)

“The location already is a gift to Penang and it depends also how we add to seafront culture and how we design the specialness.” (Consumer Advocate)

However, it was also raised that rivers are often polluted and the smell can be a barrier to walking along them.

“The smell of polluted rivers, streams and waste is unpleasant makes walking past unpleasant and unhappy.” (Health Professional)

“People like going for exercise along the river as it is nice and cool, however, it smells. So some people travel … for a long distance where it is green and clean.” (Health Professional)

Outdoor green spaces

One of George Town’s strengths is the large number of mature trees, many of them planted the same time that heritage houses were built. Their worth to the city is recognised in a book dedicated to heritage trees and individual tree identity cards with their story. The consumer advocate noted the pride in having such trees, their preservation and their ‘cleansing ability’. However, interviewees regret the lack of focus on green spaces for everyone and point out that in the past decades, many trees were removed to build apartments and car parks. While there are some small green areas, nature-lined walking tracks connecting these small green spaces are missing, hence not encouraging people to spend time outside and walking.

“Beauty and shade convey a sense of calm and make it more appealing to walk and it will bring more people to the area.” (Health Professional)

Sustainable and green public spaces development was identified as a feature of the city:

“Urban design is considering tree planting and not just at the larger park scale but also within the city itself. The Armenian Street pocket park, the Esplanade, the youth park or the traffic garden, which incorporates miniature lanes for children to practice road rules and encourages interaction between parents and children.” (Consumer Advocate)

“There are various parties that work actively on sustainable and green public spaces development, which helps mental health.” (Planner)

However, it was noted that well-off communities had such green paths for jogging and meeting people. Green spaces highlighted such as Bukit Dumbar park built in the late 1060’s and a large botanical garden may not be accessed equally among residents:

“This Botanical garden is well utilised but it seems like very few of them are from the lower socio-economic group. The awareness is not wide enough. Some people from the lower income groups might feel intimidated to use this public space.” (Consumer Advocate)

“During the 1970s, developments always included an accessible public park nearby. Pulau Tikus is an example of such a people’s park. Unfortunately, this practice seems no longer being used.” (Consumer Advocate)

Stronger collaboration between public and private sector was suggested to strengthen opportunities for creating green spaces:

“The responsibility of the developer is to cut cost and not to contribute to the public, thus the collaboration between government and private sector will benefit public space.” (Planner)

Water

George Town is surrounded by the sea on two sides and has a few rivers. Interviewees reported the calming and de-stressing effect of being able to look at flowing water and hearing it.

“Being able feel the breeze of the see while being able to see the forest provides for a sense of calmness”. (Health Professional)

“Walking along a river can be very calming.” (Health Professional)

“Water views and sound are calming” (Health Professional)

“One other significant stories of design in Penang is shape. The shape of the Penang island is like a piece of cake, both sides of the cake are facing the sea. This creates a certain amount of openness and character, with the breeze and sights, makes you fall in love with the place. The joy of seeing the hill (still highly forested), at the middle of the ‘cake’, is highly spectacular.” (Consumer Advocate)

“The location already is a gift to Penang and it depends also how we add to seafront culture and how we design the specialness.” (Consumer Advocate)

However, it was also raised that rivers are often polluted and the smell can be a barrier to walking along them.

“The smell of polluted rivers, streams and waste is unpleasant makes walking past unpleasant and unhappy.” (Health Professional)

“People like going for exercise along the river as it is nice and cool, however, it smells. So some people travel … for a long distance where it is green and clean.” (Health Professional)

Outdoor green spaces

One of George Town’s strengths is the large number of mature trees, many of them planted the same time that heritage houses were built. Their worth to the city is recognised in a book dedicated to heritage trees and individual tree identity cards with their story. The consumer advocate noted the pride in having such trees, their preservation and their ‘cleansing ability’. However, interviewees regret the lack of focus on green spaces for everyone and point out that in the past decades, many trees were removed to build apartments and car parks. While there are some small green areas, nature-lined walking tracks connecting these small green spaces are missing, hence not encouraging people to spend time outside and walking.

“Beauty and shade convey a sense of calm and make it more appealing to walk and it will bring more people to the area.” (Health Professional)

Sustainable and green public spaces development was identified as a feature of the city:

“Urban design is considering tree planting and not just at the larger park scale but also within the city itself. The Armenian Street pocket park, the Esplanade, the youth park or the traffic garden, which incorporates miniature lanes for children to practice road rules and encourages interaction between parents and children.” (Consumer Advocate)

“There are various parties that work actively on sustainable and green public spaces development, which helps mental health.” (Planner)

However, it was noted that well-off communities had such green paths for jogging and meeting people. Green spaces highlighted such as Bukit Dumbar park built in the late 1060’s and a large botanical garden may not be accessed equally among residents:

“This Botanical garden is well utilised but it seems like very few of them are from the lower socio-economic group. The awareness is not wide enough. Some people from the lower income groups might feel intimidated to use this public space.” (Consumer Advocate)

“During the 1970s, developments always included an accessible public park nearby. Pulau Tikus is an example of such a people’s park. Unfortunately, this practice seems no longer being used.” (Consumer Advocate)

Stronger collaboration between public and private sector was suggested to strengthen opportunities for creating green spaces:

“The responsibility of the developer is to cut cost and not to contribute to the public, thus the collaboration between government and private sector will benefit public space.” (Planner)

Figure 1: Armenian Park, Penang (Source: Think City)

Green space was also noted as a way to manage urban heat:

“The mini park opposite CIMB Bank at Pulau Tikus is a good example that even small parks make a difference but they need good shade to make it less hot. We need more parks like that to sit down.” (Health Professional)

“The mini park opposite CIMB Bank at Pulau Tikus is a good example that even small parks make a difference but they need good shade to make it less hot. We need more parks like that to sit down.” (Health Professional)

Figure 2: Pulau Tikus Linear Street Pocket Park (Source: Think City)

Green space and buildings

Nature should be incorporated into buildings, on façades, and even within –“let rain and sunlight in” said one architect, as it provides a good connection to nature. Sekeping Victoria provides a good example of this, a town house that incorporates trees within it, transforming the space. George Town has plenty of these spaces, providing ample opportunities for creative use of space. Unfortunately, the traditional shophouses are either replaced by new buildings or their courtyards enclosed into fully air-conditioned buildings to control for sun and heat. “The space becomes ‘devoid of soul’ – without natural sunlight and air ventilation”. (Architect)

Nature should be incorporated into buildings, on façades, and even within –“let rain and sunlight in” said one architect, as it provides a good connection to nature. Sekeping Victoria provides a good example of this, a town house that incorporates trees within it, transforming the space. George Town has plenty of these spaces, providing ample opportunities for creative use of space. Unfortunately, the traditional shophouses are either replaced by new buildings or their courtyards enclosed into fully air-conditioned buildings to control for sun and heat. “The space becomes ‘devoid of soul’ – without natural sunlight and air ventilation”. (Architect)

Case study: Green Connectors Project

The Penang Green Connectors Project, which will see the development of various parks and amenities on a massive 18,000ha of the island, is beginning to take shape from 2019 as part of the state’s Penang Vision 2030 target. Following mapping by Think City, the implementation will involve various government agencies from the Drainage and Irrigation Department to the Forestry Department. The project is a collaborative effort between George Town Conservation and Development Corporation Sdn Bhd (GTCDC) and Penang Island City Council (MBPP) and will create:

The 18,000ha will form a green network, including the creation of 50km of coastal parks and 65km of “blue connectors” or rivers. This will significantly increase waterfront recreational amenities for Penangites with environmental benefits such as the creation of ecological corridors which will have cooling effects to mitigate climate change. Once completed, the route will allow pedestrians to walk, run or cycle from Botanic Gardens to Gurney Wharf as included in the Local Council’s Bicycle Route Master Plan.

Further information here.

- Coastal parks stretching from Tanjung Tokong in George Town to Batu Maung in the South of the Island

- Linear parks along existing rivers to connect the sea to Penang’s hills.

The 18,000ha will form a green network, including the creation of 50km of coastal parks and 65km of “blue connectors” or rivers. This will significantly increase waterfront recreational amenities for Penangites with environmental benefits such as the creation of ecological corridors which will have cooling effects to mitigate climate change. Once completed, the route will allow pedestrians to walk, run or cycle from Botanic Gardens to Gurney Wharf as included in the Local Council’s Bicycle Route Master Plan.

Further information here.

Figure 3: Climate Adaptation Plan

Active places

George Town is well known within and outside of Malaysia for its food and food culture attracting many visitors. A culture of health and wellbeing, particularly being physically active, is missing or restricted to higher income groups. While non-communicable disease statistics are alarming, consideration for health as part of urban planning was seen as lacking, hence not creating the spaces necessary to encourage physical activity (the lack of nature-lined pedestrian-friendly roads was also noted, and the unpleasant smell of the river deterring physical activity were both noted in the green spaces section).

However, one of the consumer advocates started a youth park, and an adventure playground was created with the purpose of bringing three generations together to be physically active through archery, skating, walking or abseiling. It also includes a theatre and camping site for scout groups and others. The concept of the park was to be accessible and bringing the jungle environment close to the heart of the city.

Places like the botanical garden, youth park, Padang Brown and other small gardens are great places for people to be active. These places were originally planned by the British during the colonial times so that each housing estate has access to its ‘green lung’ where people can play football, walk, sit and read. The advocate feels that this urban design practice unfortunately has not continued.

However, one of the consumer advocates started a youth park, and an adventure playground was created with the purpose of bringing three generations together to be physically active through archery, skating, walking or abseiling. It also includes a theatre and camping site for scout groups and others. The concept of the park was to be accessible and bringing the jungle environment close to the heart of the city.

Places like the botanical garden, youth park, Padang Brown and other small gardens are great places for people to be active. These places were originally planned by the British during the colonial times so that each housing estate has access to its ‘green lung’ where people can play football, walk, sit and read. The advocate feels that this urban design practice unfortunately has not continued.

Figure 4: Botanical Gardens, Penang (Source: Think City)

“Places that allow you to walk and breath freely are good for mental health.” (Consumer Advocate)

“Spaces with a mixed-use function are good for mental health.” (Planner)

Another important aspect to cultivate a good mental health within the community is to have an active space where residents can gather and exercise together. Yet these spaces are often lacking. In the current Malaysian housing estate design, there is a lack of active community space where residents can meet and be empowered to maintain a healthy lifestyle together. This is especially apparent for the elderly people as there is little to no gathering spaces except for the children’s playground.

“No allocation in housing estates for ‘club’ where they [residents]can meet and empower them. Small allocation for children’s playgrounds but not for the elderly.” (Health Professional)

Transportation and walkability

While there are some pedestrian-friendly walkways in George Town, the car culture and dependency are very strong. According to a consumer advocate: “We need to move from a CAR-ing to a caring culture..."

In addition to noise and pollution cars have created, the small streets of George Town are not wide enough for car and pedestrian infrastructure, leading to being stuck in traffic congestion and being in danger of pedestrians being stuck by cars, making it very difficult to walk around:

“The chaotic traffic, people cutting across causing stress for drivers and causes bad mood.” (Health Professional)

“You can walk from Gurney drive but there is no pedestrian crossing. Gurney drive is shaded but connectivity could be better for pedestrians. The road is hard to cross. Traffic lights should be installed.” (Health Professional)

Walkability is even more of a challenge for those with mobility issues, including the ageing population, and discourages them from venturing out. For instance, in George Town bus stops benches have been removed and replaced with steel tubes as a prevention for homelessness but this can be uncomfortable for sitting. A universal design for public amenities for everyone to utilise would be helpful, and this should apply indoors as well.

“Do we have facilities and infrastructure of older people? This part of town planning is lacking, there is no thinking about it. New condominiums are not suitable, no anti slip surfaces, ramps, wider doors.” (Health Professional)

While congestion is a feature of most cities, many feel the George Town UNESCO heritage area could address some of the challenge by reviving traditional transport options:

'The biggest tragedy of Penang is the moving away from public transport system [including rikshaws and electric trolleys] and the dependency on the automobile”. (Consumer advocate)

“Council is trying hard and offering many activities but for example where would you put cycle paths? There is no space. We have free buses, but we should have the trams back.” (Health Professional)

Other approaches may also help encourage walking and public transport use, for instance, incentives, improved connectivity, and schemes like establishing a heritage/ food trail; and ensuring accessibility for all.

More covered walkways are needed for protection from sun and rain, more shade and shrubs. Making walkways more comfortable will avoid jay walking.” (Health Professional)

“Universal access also must be prioritised as improved accessibility will stimulate the senses and improve mental health of all sectors of the community.” (Planner)

Other suggested solutions may not be infrastructure-based but can be flexible scheduling:

“Commuting to work is stretching longer and longer. In Penang, it could take up to 2 hours to commute to work. One solution to this is to professional for flexi hours or working from home.” (Health Professional)

However, even staying at home, traffic can contribute reduced mental wellbeing through noise pollution.

“Good insulation can reduce stress produced by exposure to noise from traffic.” (Health Professional)

Only one interviewee mentioned air pollution. This was in relation to the predominant car culture:

“We also need to look at reducing emissions, maybe move to electric cars.” (Health Professional)

Another suggestion to turn the current car and passenger ferry into a high-frequency passenger ferry only would also reduce emissions and enhance the active transport infrastructure.

“Spaces with a mixed-use function are good for mental health.” (Planner)

Another important aspect to cultivate a good mental health within the community is to have an active space where residents can gather and exercise together. Yet these spaces are often lacking. In the current Malaysian housing estate design, there is a lack of active community space where residents can meet and be empowered to maintain a healthy lifestyle together. This is especially apparent for the elderly people as there is little to no gathering spaces except for the children’s playground.

“No allocation in housing estates for ‘club’ where they [residents]can meet and empower them. Small allocation for children’s playgrounds but not for the elderly.” (Health Professional)

Transportation and walkability

While there are some pedestrian-friendly walkways in George Town, the car culture and dependency are very strong. According to a consumer advocate: “We need to move from a CAR-ing to a caring culture..."

In addition to noise and pollution cars have created, the small streets of George Town are not wide enough for car and pedestrian infrastructure, leading to being stuck in traffic congestion and being in danger of pedestrians being stuck by cars, making it very difficult to walk around:

“The chaotic traffic, people cutting across causing stress for drivers and causes bad mood.” (Health Professional)

“You can walk from Gurney drive but there is no pedestrian crossing. Gurney drive is shaded but connectivity could be better for pedestrians. The road is hard to cross. Traffic lights should be installed.” (Health Professional)

Walkability is even more of a challenge for those with mobility issues, including the ageing population, and discourages them from venturing out. For instance, in George Town bus stops benches have been removed and replaced with steel tubes as a prevention for homelessness but this can be uncomfortable for sitting. A universal design for public amenities for everyone to utilise would be helpful, and this should apply indoors as well.

“Do we have facilities and infrastructure of older people? This part of town planning is lacking, there is no thinking about it. New condominiums are not suitable, no anti slip surfaces, ramps, wider doors.” (Health Professional)

While congestion is a feature of most cities, many feel the George Town UNESCO heritage area could address some of the challenge by reviving traditional transport options:

'The biggest tragedy of Penang is the moving away from public transport system [including rikshaws and electric trolleys] and the dependency on the automobile”. (Consumer advocate)

“Council is trying hard and offering many activities but for example where would you put cycle paths? There is no space. We have free buses, but we should have the trams back.” (Health Professional)

Other approaches may also help encourage walking and public transport use, for instance, incentives, improved connectivity, and schemes like establishing a heritage/ food trail; and ensuring accessibility for all.

More covered walkways are needed for protection from sun and rain, more shade and shrubs. Making walkways more comfortable will avoid jay walking.” (Health Professional)

“Universal access also must be prioritised as improved accessibility will stimulate the senses and improve mental health of all sectors of the community.” (Planner)

Other suggested solutions may not be infrastructure-based but can be flexible scheduling:

“Commuting to work is stretching longer and longer. In Penang, it could take up to 2 hours to commute to work. One solution to this is to professional for flexi hours or working from home.” (Health Professional)

However, even staying at home, traffic can contribute reduced mental wellbeing through noise pollution.

“Good insulation can reduce stress produced by exposure to noise from traffic.” (Health Professional)

Only one interviewee mentioned air pollution. This was in relation to the predominant car culture:

“We also need to look at reducing emissions, maybe move to electric cars.” (Health Professional)

Another suggestion to turn the current car and passenger ferry into a high-frequency passenger ferry only would also reduce emissions and enhance the active transport infrastructure.

Pro-Social spaces to encourage positive social interaction

“Urban design can increase the level of interaction between people” (Planner). And yet the theme emerging in several categories is that health-promoting urban environments are found less often where poorer people live: “Where people live has a big impact on their state of mind”.

From an urban planning perspective, the consumer advocate proposed that public spaces should be close to people’s homes, no matter where they lived or what income they had. They regretted that public spaces were declining as they had been transformed into roads or parking.

In George Town, shopping streets such as Lebuh Campbell and Lebuh Chulia and many of the little lanes offered a mix of social and commercial activities contributing to their vibrancy. Rows of shophouses where people lived upstairs facilitated social interaction.

Unique to George Town are the wooden homes built from Bakau, mangrove forest wood, on jetties into the water between Penang Island and the mainland. These informal settlements were built by homeless people and demonstrate the strong social support amongst them. Each jetty hosts a different clan specialising in different trades. “It is unique to have urban design that builds up from the grass roots onwards from people that are also entrepreneurs” (Consumer Advocate) However, these jetties are now a tourist attraction, and many feel their privacy is being invaded.

From an urban planning perspective, the consumer advocate proposed that public spaces should be close to people’s homes, no matter where they lived or what income they had. They regretted that public spaces were declining as they had been transformed into roads or parking.

In George Town, shopping streets such as Lebuh Campbell and Lebuh Chulia and many of the little lanes offered a mix of social and commercial activities contributing to their vibrancy. Rows of shophouses where people lived upstairs facilitated social interaction.

Unique to George Town are the wooden homes built from Bakau, mangrove forest wood, on jetties into the water between Penang Island and the mainland. These informal settlements were built by homeless people and demonstrate the strong social support amongst them. Each jetty hosts a different clan specialising in different trades. “It is unique to have urban design that builds up from the grass roots onwards from people that are also entrepreneurs” (Consumer Advocate) However, these jetties are now a tourist attraction, and many feel their privacy is being invaded.

Figure 5: Clan jetties (Source: Think City)

Third spaces v transition spaces

Planners identified a need to create small, intimate spaces where people can interact. This community building and designing for mental health is seen as particularly important for young people who often are overly dependent on the virtual world, and for the older people who feel marginalised as they increasingly lose their community and sense of belonging.

A good example of an inviting, inclusive space is the entrance to the Penang Times Square, which has been set-back, contains a water feature, sculpture and other flexible spaces. They are engaging in contrast to places such as Padang Kota which acts primarily as a transition space.

“Third spaces for social interaction are important. They need to be social places and I call them happy places,” said a health professional. A happy space is a mental health-promoting environment. For example, buildings with high ceilings can be beneficial for a person as it gives a sense of openness and not being closed in.

An architect explains that besides parks and gardens, courtyards and the typical historic five-foot covered walkways can also become these in-between spaces. They bring together the outdoors and indoors as well as the public and private spaces. However, a health professional points out that the sprouting of small businesses on a 5-foot pathway can also hinder the flow of pedestrian traffic leading to congestion on the walkway and pushing foot traffic into the road. A balance between socialising and safety needs to be found.

Public spaces for social interaction across all ages and activities also promotes mental health. George Town has many community halls that could be used more frequently.

“The high-end middle class have formed associations and rent halls for line-dancing. Community halls should be reserved for older people for their activities. Many are now living alone and these activities help overcome their social isolation and build social networks. This social capital helps. If one person does not show up, others check on them. It is low tech and builds ownership, it is doable… For example, in Japan, they have an alarm system for older people who are living alone, whereas for Malaysia, we have the smell system- when neighbours smell the dead body.” (Health Professional)

Planners identified a need to create small, intimate spaces where people can interact. This community building and designing for mental health is seen as particularly important for young people who often are overly dependent on the virtual world, and for the older people who feel marginalised as they increasingly lose their community and sense of belonging.

A good example of an inviting, inclusive space is the entrance to the Penang Times Square, which has been set-back, contains a water feature, sculpture and other flexible spaces. They are engaging in contrast to places such as Padang Kota which acts primarily as a transition space.

“Third spaces for social interaction are important. They need to be social places and I call them happy places,” said a health professional. A happy space is a mental health-promoting environment. For example, buildings with high ceilings can be beneficial for a person as it gives a sense of openness and not being closed in.

An architect explains that besides parks and gardens, courtyards and the typical historic five-foot covered walkways can also become these in-between spaces. They bring together the outdoors and indoors as well as the public and private spaces. However, a health professional points out that the sprouting of small businesses on a 5-foot pathway can also hinder the flow of pedestrian traffic leading to congestion on the walkway and pushing foot traffic into the road. A balance between socialising and safety needs to be found.

Public spaces for social interaction across all ages and activities also promotes mental health. George Town has many community halls that could be used more frequently.

“The high-end middle class have formed associations and rent halls for line-dancing. Community halls should be reserved for older people for their activities. Many are now living alone and these activities help overcome their social isolation and build social networks. This social capital helps. If one person does not show up, others check on them. It is low tech and builds ownership, it is doable… For example, in Japan, they have an alarm system for older people who are living alone, whereas for Malaysia, we have the smell system- when neighbours smell the dead body.” (Health Professional)

Case study: Pocket parks in laneways

The laneways in the old part of town at the back of houses, were built before modern sewage systems and just wide enough to let carts through to collect human waste. Today many of them are blocked by temporary structures, mounds of building or kitchen waste or generally neglected and used for a variety of illicit purposes. A pilot greening initiative in four laneways was started in Little India and called ‘Secret Gardens of earthly Delights’. Think City, the Kuala Lumpur based Better Cities Group and the local community designed and created the laneway gardens. It started of with conversations with owners and community and involved joint clean-up days to build a sense of ownership and purpose. The concept of a secret garden also highlighted gardens on private land adopted by a community. Design had to remain simple and adapted to the aspirations specific to each laneway community.

Based on the willingness of community to support the gardens, a second phase carried out and property owners and tenants were brought into the evaluation. After the project, the lane started to return to its previous state. Even the project was not as successful as planned, it showcased the potential of these laneways to the local authorities. It also demonstrated that for sustainable success, community engagement needed to continue following completion, with one party formally responsible for maintaining the upkeep. With the learning from this pilot, laneways in other Malaysian cities have started to be upgraded. The process and outputs have many links to mental health: as a destination or shortcut, they encourage safe walking; adopting the pocket parks builds the social capital of that street and even small greening has the calming effect of nature. (Source: Khor et al., 2013)

Based on the willingness of community to support the gardens, a second phase carried out and property owners and tenants were brought into the evaluation. After the project, the lane started to return to its previous state. Even the project was not as successful as planned, it showcased the potential of these laneways to the local authorities. It also demonstrated that for sustainable success, community engagement needed to continue following completion, with one party formally responsible for maintaining the upkeep. With the learning from this pilot, laneways in other Malaysian cities have started to be upgraded. The process and outputs have many links to mental health: as a destination or shortcut, they encourage safe walking; adopting the pocket parks builds the social capital of that street and even small greening has the calming effect of nature. (Source: Khor et al., 2013)

Figure 6: Laneways before and after (Source: Think City)

Safety in the city

In the recent survey conducted by Ipsos, participants replaced corruption with crime and violence as their main concern (39%). Crime and antisocial behaviour were linked to smoking, loitering, drug use and lack of lighting. While the UNESCO heritage core has been declared smoke free, compliance has been lacking.

“Smoking and hanging around often starts antisocial behaviour. If smoking was not allowed, much less people would avoid the area. Also, better lighting and patrolling is needed. These parts of town are neglected.” (Health Professional)

“Narrow corridors in shopping malls. These places are gloomy and dull leading to feeling unsafe, often people with drug addiction congregate and urinate there. People stay away.” (Health Professional)

Inclusive outdoor design including mature trees create safer and more accessible places that make people feel more welcome and hence improve mental health.

“Playgrounds need open air and be less trees that create dark areas so that there is always a clear view to see the children. Many people are concerned about kidnapping or molesting. Best are tall mature trees that provide shade and that clear view. Jalan Permai, Mount Erskine Road is a good example of a park with mature trees. You can see children up to 100 meters away.” (Health Professional)

“Pedestrian crossings in Penang are often overpasses which are hard to manage for people with mobility issues. Overhead pedestrian walk bridges are often avoided because they are dark, hard to walk up, dirty, ugly - leading to jay-walking.” (Health Professional)

“Smoking and hanging around often starts antisocial behaviour. If smoking was not allowed, much less people would avoid the area. Also, better lighting and patrolling is needed. These parts of town are neglected.” (Health Professional)

“Narrow corridors in shopping malls. These places are gloomy and dull leading to feeling unsafe, often people with drug addiction congregate and urinate there. People stay away.” (Health Professional)

Inclusive outdoor design including mature trees create safer and more accessible places that make people feel more welcome and hence improve mental health.

“Playgrounds need open air and be less trees that create dark areas so that there is always a clear view to see the children. Many people are concerned about kidnapping or molesting. Best are tall mature trees that provide shade and that clear view. Jalan Permai, Mount Erskine Road is a good example of a park with mature trees. You can see children up to 100 meters away.” (Health Professional)

“Pedestrian crossings in Penang are often overpasses which are hard to manage for people with mobility issues. Overhead pedestrian walk bridges are often avoided because they are dark, hard to walk up, dirty, ugly - leading to jay-walking.” (Health Professional)

Economic stress, housing, and affordability in the city

The link between good design and mental wellbeing was well understood but it was felt that good design was very unequally distributed and mainly “the privilege of the elite”. - Consumer Advocate

George Town and wider Penang are seen as a good place for retirement including for those from overseas, due to its good private and public healthcare system:

“Good weather, good for arthritis, affordable to live, good English, the seas & hills.” - Health Professional

For many overseas residents, the local lifestyle is still very affordable. However, as George Town’s heritage core is restored and more visitors come, residential property is either becoming much more expensive or turned into visitor accommodation. Both impact mental health, because housing is no longer affordable or because tenants are evicted to make way for tourists.

Being homeless is a strain on mental health but also affects the feeling of safety of other community members. Furthermore, standing as the tallest building in Penang, KOMTAR was once the pride and glory of Penang to revitalise the city state, but now:

“Komtar at night: lots of homeless people. Who is caring for them? Society has failed them.” - Health Professional

“Mental health is sensitive issue, you see them lying around sleeping, you can tell from the way they are dressed. Nothing is done unless someone complains” - Health Professional

In terms of addressing the housing situation, “Much bolder urban design thinking is need to overcome current challenges”, according to a Consumer Advocate. Those challenges range from better waste management to healthier housing for the urban poor and generally prioritising people’s wellbeing over profits. “Here everyone wants to just build bigger rather than focus on people.” - Health Professional

Respondents felt that high density development without the necessary public and green spaces, particularly for the urban poor, is leading to overcrowding and waste management issues:

“Housing designed for the urban poor is terrible and detrimental for mental health and general wellbeing.” - Consumer Advocate

“There is a lack of communal spaces in low-cost housing, and lack of spaces to encourage interaction between different segments of society. There is insufficient infrastructure to deal with mental health.” - Architect

“Sungai Pinang (housing for urban poor) area is small, congested, no space for children, no proper space for waste disposal. People throw rubbish over the balcony. There are no parks in the vicinity.” - Consumer Advocate

This is contrasted with downtown George Town and the traditional houses with their air wells that circulate the air and bring sunlight to the middle of the house.

A different voice argued for involving the residents of such housing to extend responsible behaviour from the flat to the housing block which might also have some pro-social benefits: “Change social norms: it is like changing the software (mindset) in addition to the hardware (infrastructure). For example, housing estates have lifts but they are dirty and smelly. People don’t look after them. Particularly in PPRs. Give ownership to people and stigmatise bad behaviour, not keep repairing.” - Health Professional.

There was recognition of the impact of the environment, particularly housing, on health and a desire for stronger health input into design and monitoring. “There is limited to no system for health professionals to influence environmental design in the city. There is, however, a midwife outreach program which caters to pregnant women in rural areas. The midwives would assess housing, water and sanitation.” - Health Professional

George Town and wider Penang are seen as a good place for retirement including for those from overseas, due to its good private and public healthcare system:

“Good weather, good for arthritis, affordable to live, good English, the seas & hills.” - Health Professional

For many overseas residents, the local lifestyle is still very affordable. However, as George Town’s heritage core is restored and more visitors come, residential property is either becoming much more expensive or turned into visitor accommodation. Both impact mental health, because housing is no longer affordable or because tenants are evicted to make way for tourists.

Being homeless is a strain on mental health but also affects the feeling of safety of other community members. Furthermore, standing as the tallest building in Penang, KOMTAR was once the pride and glory of Penang to revitalise the city state, but now:

“Komtar at night: lots of homeless people. Who is caring for them? Society has failed them.” - Health Professional

“Mental health is sensitive issue, you see them lying around sleeping, you can tell from the way they are dressed. Nothing is done unless someone complains” - Health Professional

In terms of addressing the housing situation, “Much bolder urban design thinking is need to overcome current challenges”, according to a Consumer Advocate. Those challenges range from better waste management to healthier housing for the urban poor and generally prioritising people’s wellbeing over profits. “Here everyone wants to just build bigger rather than focus on people.” - Health Professional

Respondents felt that high density development without the necessary public and green spaces, particularly for the urban poor, is leading to overcrowding and waste management issues:

“Housing designed for the urban poor is terrible and detrimental for mental health and general wellbeing.” - Consumer Advocate

“There is a lack of communal spaces in low-cost housing, and lack of spaces to encourage interaction between different segments of society. There is insufficient infrastructure to deal with mental health.” - Architect

“Sungai Pinang (housing for urban poor) area is small, congested, no space for children, no proper space for waste disposal. People throw rubbish over the balcony. There are no parks in the vicinity.” - Consumer Advocate

This is contrasted with downtown George Town and the traditional houses with their air wells that circulate the air and bring sunlight to the middle of the house.

A different voice argued for involving the residents of such housing to extend responsible behaviour from the flat to the housing block which might also have some pro-social benefits: “Change social norms: it is like changing the software (mindset) in addition to the hardware (infrastructure). For example, housing estates have lifts but they are dirty and smelly. People don’t look after them. Particularly in PPRs. Give ownership to people and stigmatise bad behaviour, not keep repairing.” - Health Professional.

There was recognition of the impact of the environment, particularly housing, on health and a desire for stronger health input into design and monitoring. “There is limited to no system for health professionals to influence environmental design in the city. There is, however, a midwife outreach program which caters to pregnant women in rural areas. The midwives would assess housing, water and sanitation.” - Health Professional

Case study: Hock Teik affordable housing scheme

Several factors have contributed to George Town heritage core losing community. Since becoming a UNESCO world heritage city, gentrification has threatened lower income tenants. As property owners are restoring their buildings to increase value, higher rent or tenancy insecurity requires them to move. The houses near Hock Teik Temple and owned by the Hock Teik Society have been occupied by lower income Chinese families for generations, who have often lived there since migration from China and representing intangible heritage of skills and traditions. To maintain the social fabric of this area, a public-private sector affordable housing scheme was piloted.

The proposition of this pilot was for property owners to freeze rents and provide tenancy agreements for 10 years while also upgrading the buildings. Many discussions were needed to build trust between the parties. Critical success factors were that one of the owners became a champion as he was keen to keep the tenants. Another factor was that the tenants as a group took ownership for the planning and renovation process. They visited each other’s houses, appreciating that their own house may not be the one most in need for improvements and prioritising the work according to need. The initiative was funded through a Community Development Fund bringing together Think City and the Asian Coalition of Housing Rights as funding agencies, the Hock Teik Society and Tenants.

Affordability, tenancy security, improved housing condition and stronger social fabric would all contribute to better mental health.

The proposition of this pilot was for property owners to freeze rents and provide tenancy agreements for 10 years while also upgrading the buildings. Many discussions were needed to build trust between the parties. Critical success factors were that one of the owners became a champion as he was keen to keep the tenants. Another factor was that the tenants as a group took ownership for the planning and renovation process. They visited each other’s houses, appreciating that their own house may not be the one most in need for improvements and prioritising the work according to need. The initiative was funded through a Community Development Fund bringing together Think City and the Asian Coalition of Housing Rights as funding agencies, the Hock Teik Society and Tenants.

Affordability, tenancy security, improved housing condition and stronger social fabric would all contribute to better mental health.

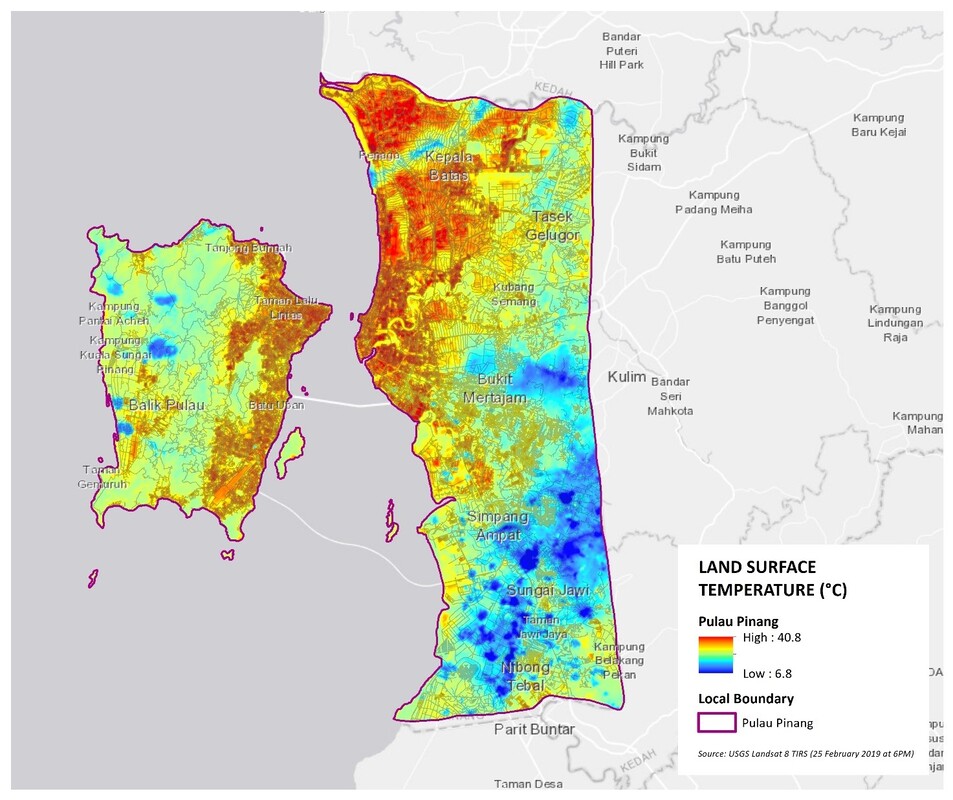

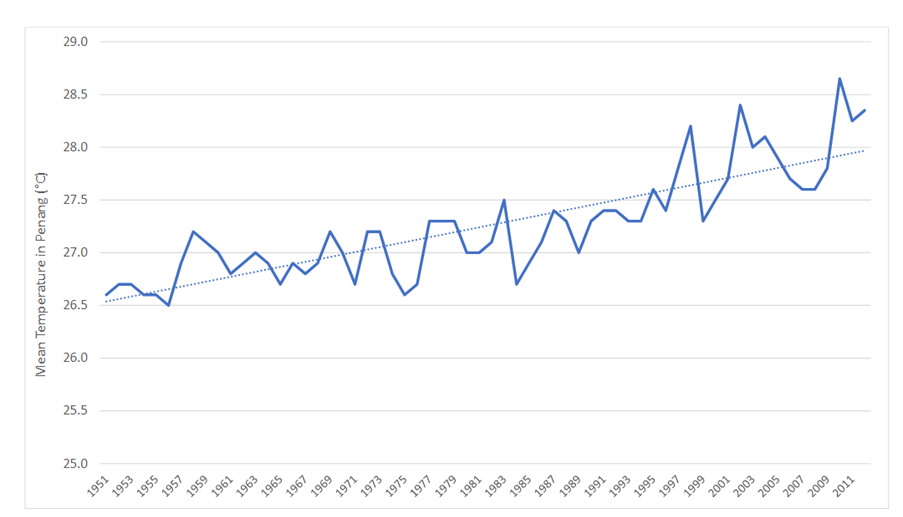

Urban heat and climate change

While urban heat is linked to green spaces, active spaces and air pollution, it should be considered its own category in a tropical city like George Town. Tropical cities will be the first to experience historically unprecedented climates. It is these hot cities where human physical and mental health are particularly vulnerable to even slight increases in temperature.

Figure 8: Satellite image showing land surface temperatures in Penang. Source: Produced by Think City using USGS Landsat 8 TIRS data, retrieved on 25 February 2019.

“Solutions need to be found to encourage walking despite the horrendous heat” - Health Professsional

“Because it is so hot during the day, people like going for exercise along the river as it is nice and cool…” - Health Professional

“There is some jay-walking now, people taking short cuts to get out of the sun quicker." - Health Professional

Comments like these demonstrate that is it already difficult to cope with the heat and the need for action to reduce urban heat. Using nature-based solutions would also help provide more green spaces such as tree-lined streets. If urban heat continues to rise, the risk is high that urban environments, no matter how inclusive and welcoming they are designed, will not be used because thermal comfort is too low. In addition to heat, George Town also experiences other severe weather events. During monsoon season, George Town is prone to flash flooding and sometimes experiences devastating landslides that have led to loss of lives in recent years. However, flooding was not mentioned by interviewees.

“Because it is so hot during the day, people like going for exercise along the river as it is nice and cool…” - Health Professional

“There is some jay-walking now, people taking short cuts to get out of the sun quicker." - Health Professional

Comments like these demonstrate that is it already difficult to cope with the heat and the need for action to reduce urban heat. Using nature-based solutions would also help provide more green spaces such as tree-lined streets. If urban heat continues to rise, the risk is high that urban environments, no matter how inclusive and welcoming they are designed, will not be used because thermal comfort is too low. In addition to heat, George Town also experiences other severe weather events. During monsoon season, George Town is prone to flash flooding and sometimes experiences devastating landslides that have led to loss of lives in recent years. However, flooding was not mentioned by interviewees.

Figure 9. Upward trend in annual median temperature in Penang. Source: Malaysian Meteorological Department (2012)

Heritage and tourism

Each of the domains linking mental health and urban design have a heritage/tourism connection. The pride in this rich cultural and natural heritage has come out clearly in the interviews. George Town as a UNESCO heritage city has seen many buildings restored. This was viewed as positive to people’s mental health. As the heritage has become alive again, people’s perspective of George Town has improved and instead of just passing through, it has turned into a place where people will spend time and celebrate. Examples are festivals, the many public murals, a unique feature of George Town, and the clan jetties:

“There is no doubt that George Town does a great job in restoring heritage by blending the old with the new. It is a glimpse into the past from the comforts of the present.” - Health Professional

“Maybe we should have a museum for urban design, to record and showcase how houses were built based on local context, such as building houses on stilts for the can jetties”. - Consumer Advocate

There is a flipside to the pride in the city’s heritage:

“The number of tourists coming in is so much that it is over-heated, for someone living there, it’s stress.” - Consumer Advocate

“The heart of George Town, the heritage area, is causing mental health problems”, says a consumer advocate and continues to explain: “Skyrocketing house prices has meant that housing has become unaffordable leading to many residents leaving the area. Those that stay complain about the tourists that see every house as public, staring into windows and taking photos, so that locals feel a critical lack of privacy leading to stress.” A health professional adds “(At Gurney drive) there are also illegal stalls obstructing but nothing is done because they bring in tourists.“

Another negative aspect is the loss of pro-social spaces:

“Rising property prices have pushed residents out, bringing in commercial occupants that do little for culture and community”. - Architect

This reduced sense of neighbourhood and community risks reducing mental wellbeing in residents in the heritage core but not in tourists.

“There is no doubt that George Town does a great job in restoring heritage by blending the old with the new. It is a glimpse into the past from the comforts of the present.” - Health Professional

“Maybe we should have a museum for urban design, to record and showcase how houses were built based on local context, such as building houses on stilts for the can jetties”. - Consumer Advocate

There is a flipside to the pride in the city’s heritage:

“The number of tourists coming in is so much that it is over-heated, for someone living there, it’s stress.” - Consumer Advocate

“The heart of George Town, the heritage area, is causing mental health problems”, says a consumer advocate and continues to explain: “Skyrocketing house prices has meant that housing has become unaffordable leading to many residents leaving the area. Those that stay complain about the tourists that see every house as public, staring into windows and taking photos, so that locals feel a critical lack of privacy leading to stress.” A health professional adds “(At Gurney drive) there are also illegal stalls obstructing but nothing is done because they bring in tourists.“

Another negative aspect is the loss of pro-social spaces:

“Rising property prices have pushed residents out, bringing in commercial occupants that do little for culture and community”. - Architect

This reduced sense of neighbourhood and community risks reducing mental wellbeing in residents in the heritage core but not in tourists.

SWOT analysis: urban design to promote good mental health in George Town

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

|

Opportunities |

Threats |

|

|

Conclusion

Lessons from George Town that could be applied to promote good mental health through urban planning and urban design lessons for better mental health

1. Tropical cities need to prioritise planning and design for thermal comfort, otherwise residents will not spend time outside whether the city is pedestrian-friendly or not (nature-based solutions for climate adaptation should be implemented).

2. Learn from traditional and historic designs that are naturally cooling and feature pro-social design.

3. Enhance natural blue and green infrastructure for equal access by all social strata.

4. In tourism destinations, clearly demarcate public and private spaces in the heritage core to protect privacy of residents and reduce their stress for better mental wellbeing.

Urban planning/design steps to help improve George Town’s public mental health

1. Invest in nature-based intervention designed not just to green but to cool the city as a climate adaptation strategy. Knowing that the city is acting on climate change and offering opportunities to participate could also alleviate climate related anxiety into the future. Any reduction in urban heat will also related mental health consequences.

2. Create eco-corridors connecting green spaces linking Penang’s central green spine to the sea to enhance recreation options and pedestrian linkages, protect biodiversity and reduce the heat island effect through nature-based cooling. In terms of mental health, this strategy would provide access to nature, increase physical activity and offer greater pro-social spaces.

3. Waterways are considered calming and need to be clean and not have an unpleasant smell to achieve their full effect on mental wellbeing. When lined by trees there is the added benefit of shading and enhanced wind corridors leading to greater cooling.