Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2019:6;9

|

CITY CASE STUDY

|

From the City of Djinns to the City of Sins: how Delhi has facilitated mental wellbeing through urban design

Kriti Agarwal

Jindal School of Art & Architecture, India

Jindal School of Art & Architecture, India

Abstract

Delhi is one of the most complex cities in the world, with its various layers and sub-cities, cultures, governance etc. Delhi, has in the last decade become infamous as being the 'rape capital of India' and 'the most polluted city in the world'. Delhi’s air is polluted not just with particulate matter but with lust for power which gets manifested in its built environment in many ways. The city sees high rates of crime. Fear has come to dominate one's life and one sees it being sold in various forms - nose masks, pepper spray, CCTV’s, air purifiers, safety apps etc.

This is all on account of the way Delhi has urbanised and expanded both pre and post independence. The sheer scale and proportion of the city is forcing individuals to yield to anonymity, indifference, and narrow self interest. These individuals with different socio-economic backgrounds have different internal environments i.e. varying Mindsets. However, as a Senior Urban Designer states that the common denominator of the Human Mind is its connection with Nature, and Urban Design is needed in maintaining this continuum between Mind and Nature and as an extension: the City.

This paper discusses if and how the city of Delhi applies the principles of urban design for good mental health and well-being of its inhabitants. It has been analysed that the city has fallen into various traps that have affected the well-being of the people. Simply put, the city has failed.

It is important to clarify in the beginning that Delhi is an extremely complicated city. It is a conglomerate of various mini-cities and to do justice to it in a Paper like this is next to impossible. This study is a start towards further research into various aspects related to urban design and mental health.

This is all on account of the way Delhi has urbanised and expanded both pre and post independence. The sheer scale and proportion of the city is forcing individuals to yield to anonymity, indifference, and narrow self interest. These individuals with different socio-economic backgrounds have different internal environments i.e. varying Mindsets. However, as a Senior Urban Designer states that the common denominator of the Human Mind is its connection with Nature, and Urban Design is needed in maintaining this continuum between Mind and Nature and as an extension: the City.

This paper discusses if and how the city of Delhi applies the principles of urban design for good mental health and well-being of its inhabitants. It has been analysed that the city has fallen into various traps that have affected the well-being of the people. Simply put, the city has failed.

It is important to clarify in the beginning that Delhi is an extremely complicated city. It is a conglomerate of various mini-cities and to do justice to it in a Paper like this is next to impossible. This study is a start towards further research into various aspects related to urban design and mental health.

Introduction

Delhi, also known as the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCTD), is the political capital of India and a city-state-Union Territory. It is located in northern India plains with the River Yamuna towards the east and the Delhi ridge originating from the Aravalli Range towards south and west. The city experiences extremely hot summers and harsh winters with spring in between and heavy rains during the annual Monsoon. It is spread over 1,484 square kilometre having a population of nearly 17 million people as per India’s Census 2011. The United Nations World Cities Report 2016 says that a further ten million people are expected to move to Delhi by 2030.

The Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health has developed the ‘Mind the GAPS’ framework for the use of architects, planners and managers to ensure sound mental health and well-being. The GAPS framework looks at green spaces and access to nature, active places, pro-social places to encourage positive social interaction, and safety in the city; and within these sectors focusing on the aspects of sleep, transportation and connection, economic stress and affordability, and air pollution. The planning and development of Delhi is analysed using this framework while highlighting specific mental health issues being faced and projects undertaken to improve well being. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 13 professionals - architects, urban designers, transport planners, and health officials. The research concludes with a SWOT analysis, identification of lessons and learnings for other cities to adopt, and suggests recommendations for the city to consider in the preparation of the Master Plan of Delhi 2041.

The Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health has developed the ‘Mind the GAPS’ framework for the use of architects, planners and managers to ensure sound mental health and well-being. The GAPS framework looks at green spaces and access to nature, active places, pro-social places to encourage positive social interaction, and safety in the city; and within these sectors focusing on the aspects of sleep, transportation and connection, economic stress and affordability, and air pollution. The planning and development of Delhi is analysed using this framework while highlighting specific mental health issues being faced and projects undertaken to improve well being. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 13 professionals - architects, urban designers, transport planners, and health officials. The research concludes with a SWOT analysis, identification of lessons and learnings for other cities to adopt, and suggests recommendations for the city to consider in the preparation of the Master Plan of Delhi 2041.

Mental health in Delhi

Like most cities, Indian cities witness high rates of most mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, stress, and schizophrenia. Contributing factors include: migration, poverty, unemployment, environmental causes such as pollution (air/noise/light), overcrowding, traffic, unhygienic living conditions, and personal crises and trauma. Add to this crime and constant fear for one’s safety. Peace of mind and happiness are forgotten terms. It is no surprise that in the World Happiness Report 2020, India was ranked 144th out of 156 countries surveyed. In 2015, India was ranked at 117.

According to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) report titled ‘Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders — Global Health Estimates’ (2015), over 50 million Indians suffered from depression, over 30 million others from anxiety disorders. (LiveMint, 2017). Depression, the most prevalent form of mental illness, is estimated to exist in 3 of every 100 in urban areas like Mumbai and of this 1 in 3 are severely neurotic (Times of India, 2012). Alzheimer’s disease was the most common of severe disorders (54%) followed by vascular dementia (39%) (HuffPost, 2016). In October 2016, the National Institute of Mental Health and NeuroSciences (NIMHANS) in Bangalore released their National Mental Health Survey that said that the incident of depression is roughly one in every twenty Indians or 5% of the population (Times of India, 2017). It was also noted that nearly 1% of the population reported high suicidal risk. The prevalence of high suicidal risk was more in the 40-49 age group (1.19%), among females (1.14%) and was maximum in those residing in urban metros (1.71%). Prevalence of mental disorders was nearly twice (13.5%) as high in urban metros compared to rural (6.9%) areas.

According to the report State of Mental Health in Delhi-2008, people in Delhi reported high levels of distress and poor subjective wellbeing both in quantitative analysis and Focus Group Discussions. The significant stressors indicated were crowded roads, larger distances, traffic problems, disturbed and erratic routines, migration of people in and out of the city resulting in a diluted culture and weak community links, lawlessness and fear for safety and security especially of women, children and elderly. It is important to note that these are all issues pertaining to city’s urbanisation. While many people reported good material wellbeing and financial status, they also reported poor overall life satisfaction and high stress levels. As a majority of the residents struggle daily to keep up with fast pace of the city dealing with diverse issues at home and work, the deteriorating physical environment of the city adds to the clutter and chaos.

Contributing factors to mental health problems in Delhi

One factor that affects mental wellbeing is fear relating to safety and security. This takes diverse forms, from air quality to sexual violence, to road danger. Delhi was declared to be the most polluted city in the world on account of extremely high PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations in its air, according to WHO’s 2014 report of the Ambient Air Pollution (AAP) (The Indian Express, 2014). The city has come to be known as the Rape Capital owing to the large number of crimes against women. Of this the brutal gang rape of a student in a bus in December 2012 led to nationwide protests and some stringent laws. But despite that the city continues to be largely unsafe for women. In June 2018, Thomson Reuters Foundation named India the most dangerous country in the world for sexual violence against women (Reuters, 2018). Delhi had more road fatalities than any other Indian city in 2015 (NDTV, 2016). The city by and large remains unfriendly towards pedestrians and cyclists, public transportation being perceived as unsafe more for women but also for men due to aggression and road rage, which also affects people in private vehicles. Police officers too have been attacked on multiple occasions. It is not uncommon to read news of a petty argument turning into a violent incident. The city has thus also come to be known as the “City of Short Fuse” (The Hindu, 2016). All of these stresses combined together have resulted in people perpetually living in fear, which is associated with the way the city has developed over the years.

According to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) report titled ‘Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders — Global Health Estimates’ (2015), over 50 million Indians suffered from depression, over 30 million others from anxiety disorders. (LiveMint, 2017). Depression, the most prevalent form of mental illness, is estimated to exist in 3 of every 100 in urban areas like Mumbai and of this 1 in 3 are severely neurotic (Times of India, 2012). Alzheimer’s disease was the most common of severe disorders (54%) followed by vascular dementia (39%) (HuffPost, 2016). In October 2016, the National Institute of Mental Health and NeuroSciences (NIMHANS) in Bangalore released their National Mental Health Survey that said that the incident of depression is roughly one in every twenty Indians or 5% of the population (Times of India, 2017). It was also noted that nearly 1% of the population reported high suicidal risk. The prevalence of high suicidal risk was more in the 40-49 age group (1.19%), among females (1.14%) and was maximum in those residing in urban metros (1.71%). Prevalence of mental disorders was nearly twice (13.5%) as high in urban metros compared to rural (6.9%) areas.

According to the report State of Mental Health in Delhi-2008, people in Delhi reported high levels of distress and poor subjective wellbeing both in quantitative analysis and Focus Group Discussions. The significant stressors indicated were crowded roads, larger distances, traffic problems, disturbed and erratic routines, migration of people in and out of the city resulting in a diluted culture and weak community links, lawlessness and fear for safety and security especially of women, children and elderly. It is important to note that these are all issues pertaining to city’s urbanisation. While many people reported good material wellbeing and financial status, they also reported poor overall life satisfaction and high stress levels. As a majority of the residents struggle daily to keep up with fast pace of the city dealing with diverse issues at home and work, the deteriorating physical environment of the city adds to the clutter and chaos.

Contributing factors to mental health problems in Delhi

One factor that affects mental wellbeing is fear relating to safety and security. This takes diverse forms, from air quality to sexual violence, to road danger. Delhi was declared to be the most polluted city in the world on account of extremely high PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations in its air, according to WHO’s 2014 report of the Ambient Air Pollution (AAP) (The Indian Express, 2014). The city has come to be known as the Rape Capital owing to the large number of crimes against women. Of this the brutal gang rape of a student in a bus in December 2012 led to nationwide protests and some stringent laws. But despite that the city continues to be largely unsafe for women. In June 2018, Thomson Reuters Foundation named India the most dangerous country in the world for sexual violence against women (Reuters, 2018). Delhi had more road fatalities than any other Indian city in 2015 (NDTV, 2016). The city by and large remains unfriendly towards pedestrians and cyclists, public transportation being perceived as unsafe more for women but also for men due to aggression and road rage, which also affects people in private vehicles. Police officers too have been attacked on multiple occasions. It is not uncommon to read news of a petty argument turning into a violent incident. The city has thus also come to be known as the “City of Short Fuse” (The Hindu, 2016). All of these stresses combined together have resulted in people perpetually living in fear, which is associated with the way the city has developed over the years.

Planning and development in Delhi

Delhi is one of the oldest planned Indian cities. Post-independence, Delhi was the first city to have a Master Plan for Delhi (MPD) - a vision and policy document prepared by the Delhi Development Authority (DDA), enforced in 1962 shaping its development for the next 20 years. Since then, MPD-2001 and MPD-2021 have shaped its growth along with various national policies. All three master plans follow a three level hierarchy i.e. City level Master Plan, Zonal Plans (15 zones) and Local Area Plans (LAP for 272 wards). A senior Urban Planner states that, “the MPD being a policy document for 20 years cannot discuss the facilitation of mental health that too through specific urban design interventions. This issue is better addressed at the scale of the LAP.” While these documents do not specifically mention ‘mental well-being’ they do aim to create a sustainable physical and social environment to provide improved quality of life. The MPD-2021 envisions Delhi as ‘a global metropolis and a world-class city, where all the people are engaged in productive work with a better quality of life, living in a sustainable environment.’ The MPD-2021 is also the first plan to have a chapter on Urban Design and discuss visual integration, conservation of heritage zones, aesthetic point of views, landscaping, street furniture, signage and urban form. The masterplan stresses the need for an urban design scheme for better design of the pedestrian realm, unhindered access movement and conservation of heritage precincts. The plan talks about linking various open spaces and ecological features like the Ridge and River Yamuna; clean and litter free public spaces; road beautification and incorporating public art in the city’s spatial experience.

Currently, the MPD-2041 is under formulation, presenting a huge opportunity for the city to focus on improving the mental well-being and learning from past failures. But before analysing the development of Delhi it is important to get a sense of its history and administrative setup.

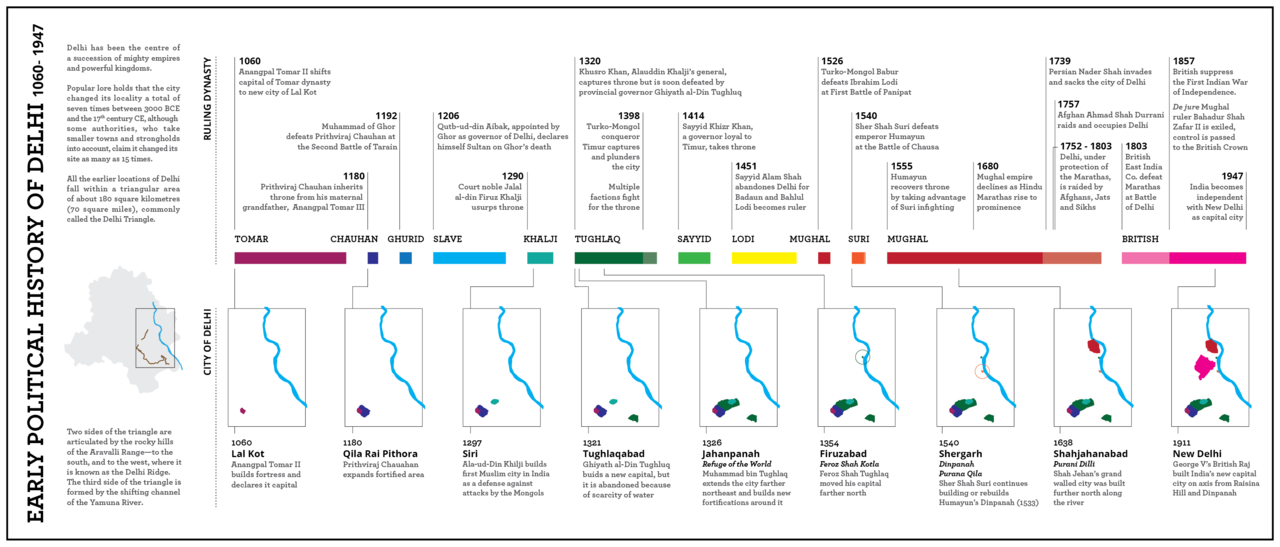

Throughout history Delhi has been the capital of various empires dating back to 6th century BC capital of Indraprastha to the old city of Shahajahanabad- the Mughal Capital; to being the colonial British Capital and then the political capital of newly independent India. The city has always been in a Capitalistic position and this has embedded the notion of ‘Power’ in its air. Battle after battle has been fought and the city has oscillated between times of peace and glory to extreme unrest. Each era has left its mark in the city’s built fabric, ruins of one capital added next to its ancestor’s. A new capital built on the foundation of the previous. Even post-independence the city has witnessed acts of violence and discrimination such as during the India-Pakistan partition, National Emergency of 1975 and 1984 Sikh riots.

Currently, the MPD-2041 is under formulation, presenting a huge opportunity for the city to focus on improving the mental well-being and learning from past failures. But before analysing the development of Delhi it is important to get a sense of its history and administrative setup.

Throughout history Delhi has been the capital of various empires dating back to 6th century BC capital of Indraprastha to the old city of Shahajahanabad- the Mughal Capital; to being the colonial British Capital and then the political capital of newly independent India. The city has always been in a Capitalistic position and this has embedded the notion of ‘Power’ in its air. Battle after battle has been fought and the city has oscillated between times of peace and glory to extreme unrest. Each era has left its mark in the city’s built fabric, ruins of one capital added next to its ancestor’s. A new capital built on the foundation of the previous. Even post-independence the city has witnessed acts of violence and discrimination such as during the India-Pakistan partition, National Emergency of 1975 and 1984 Sikh riots.

Figure 1: Early political history of Delhi.

But behind the political tension lies a mystical side to the city, making Delhi famous as the Sufi Capital of India. The glory of Shahajahanabad is a favourite of poets; the old city having hosted Mirza Ghalib, the legendary Urdu poet for whom Delhi was the soul-of-the-world. The city itself was nominated for UNESCO World Heritage City for its Outstanding Universal Value based on its four precincts - Mehrauli, Nizamuddin, Shahjahanabad and New Delhi; the nomination was withdrawn but may be resubmitted. The city is already home to three UNESCO World Heritage Sites - Red Fort Complex, Qutab Minar, and Humayun’s Tomb. Along with these the city’s fabric is in a way held together by many protected and unprotected heritage monuments interspersed with the urban areas developed post independent. Even today the city with its many layers of history continues to fascinate authors and poets. William Dalrymple wrote about Delhi being a city with ‘a bottomless seam of stories’ in his book City of Djinns.

Administrative set-up Being a capital city and a Union Territory, Delhi is jointly administered by the federal Government of India (GoI) and the State Government of Delhi. As a result its growth and development is not just shaped by the Master Plans prepared by DDA but by various authorities working mostly independently of each other. Of these the following are under GOI: the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), the National Capital Regional Planning Board (NCRPB), the Delhi Urban Arts Commission (DUAC), and the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC). Besides these the Public Works Department (PWD), Dialogue and Development Commission of Delhi, Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) are amongst the Delhi government authorities. The urban management of the city and proper implementation of the master plans and building bye-laws is the responsibility of four Municipal Corporations - New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC), North Delhi Municipal Corporation (MCD-N), East Delhi Municipal Corporation (EDMC), and South Delhi Municipal Corporation (SDMC) and the Delhi Cantonment Board. It is interesting to note that this multiplicity of organisation and their working in almost isolation w.r.t. each other though appalling is actually representative of the city itself.

Delhi’s growth is shaped by various National, State and City level policies and plans. The Master Plan of Delhi however, continues to be the most important planning document for the city specifying overall vision, land use distribution, infrastructure provision as well as development controls and building by-laws.

City of Mini Cities

Besides the various layers added over time, today’s Delhi when looked at through the urban lens comprises various typologies of settlements each having a very unique character, role and issues. The Master Plan categorises them as Special Areas of Walled City of Shahajahanabad and its extensions and Karol Bagh; Lutyens Bungalow Zone, Urbanised Villages and their extensions; planned plotted developments; low density government housing (under GoI); sub-cities of Dwarka,

Rohini and Narela (first proposed in MPD-2001); and unplanned areas including slums, JJ clusters, resettlement colonies, and unauthorised colonies. Overall the MPD-2021 defines Delhi’s density at 250pph but within these different typologies we see huge variations in density.

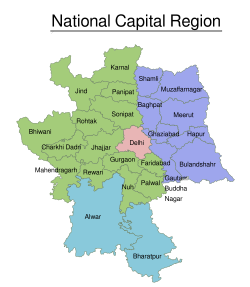

While Delhi has these many smaller cities within it, it itself is also part of the National Capital Region (NCR) which was defined with the concurrence of the participating States of Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh in 1985 under the National Capital Region Planning Board Act by the Government of India, to provide for the projected phenomenal increase in population (National Capital Region Planning Board, 2017).

Administrative set-up Being a capital city and a Union Territory, Delhi is jointly administered by the federal Government of India (GoI) and the State Government of Delhi. As a result its growth and development is not just shaped by the Master Plans prepared by DDA but by various authorities working mostly independently of each other. Of these the following are under GOI: the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), the National Capital Regional Planning Board (NCRPB), the Delhi Urban Arts Commission (DUAC), and the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC). Besides these the Public Works Department (PWD), Dialogue and Development Commission of Delhi, Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) are amongst the Delhi government authorities. The urban management of the city and proper implementation of the master plans and building bye-laws is the responsibility of four Municipal Corporations - New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC), North Delhi Municipal Corporation (MCD-N), East Delhi Municipal Corporation (EDMC), and South Delhi Municipal Corporation (SDMC) and the Delhi Cantonment Board. It is interesting to note that this multiplicity of organisation and their working in almost isolation w.r.t. each other though appalling is actually representative of the city itself.

Delhi’s growth is shaped by various National, State and City level policies and plans. The Master Plan of Delhi however, continues to be the most important planning document for the city specifying overall vision, land use distribution, infrastructure provision as well as development controls and building by-laws.

City of Mini Cities

Besides the various layers added over time, today’s Delhi when looked at through the urban lens comprises various typologies of settlements each having a very unique character, role and issues. The Master Plan categorises them as Special Areas of Walled City of Shahajahanabad and its extensions and Karol Bagh; Lutyens Bungalow Zone, Urbanised Villages and their extensions; planned plotted developments; low density government housing (under GoI); sub-cities of Dwarka,

Rohini and Narela (first proposed in MPD-2001); and unplanned areas including slums, JJ clusters, resettlement colonies, and unauthorised colonies. Overall the MPD-2021 defines Delhi’s density at 250pph but within these different typologies we see huge variations in density.

While Delhi has these many smaller cities within it, it itself is also part of the National Capital Region (NCR) which was defined with the concurrence of the participating States of Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh in 1985 under the National Capital Region Planning Board Act by the Government of India, to provide for the projected phenomenal increase in population (National Capital Region Planning Board, 2017).

Figure 2: Delhi's National Capital Region.

The Regional Plan-2021 prepared under this act provides for "a model for sustainable development of urban and rural settlements to improve quality of life as well as a rational regional land use pattern to protect and preserve good agricultural land, environmentally sensitive areas and utilise unproductive land for urban areas through an inter-related policy framework relating to settlement systems, economic activities, transportation, telecommunication, regional land use, infrastructural facilities such as power and water, social infrastructure, environment, disaster management, heritage and tourism."

Health impacts of the growing population of Delhi

As per the decadal data of the Census of India, the population of Delhi has increased from 40.66 lakh (over 4 million) in 1971 to 138.5 lakh in 2001 (nearly 14 million). The in-migration during same period has increased from 8.76 lakh (800,760) in 1971 to 22.22 lakh (over 2 million) in 2001. The share of out-migration from Delhi has slightly increased from 2.42 lakh in 1961-71 to 4.58 lakh in 1991-2001. The net migrants (in-migrants – out-migrants) have steadily increased from 6.34 lakh during 1961-71 to 17.64 lakh during 1991-2001. (National Capital Regional Planning Board, 2001). In 2016 the population of Delhi grew by nearly 1,000 a day, of which over 300 were migrants who came to the city to settle down. The share of migrants in the capital’s population growth thus reached 33% in 2016 — highest in 15 years (Times of India, 2018). Delhi therefore, also got the tag of the ‘Migrant Capital’ of India owing to the large number of service sector jobs it offers along with the highest per capita income among states. A senior Urbanist states: "Delhi concentrates much more on wealth, resources, infrastructure and quality of urban services than other metros. The national capital offers a relatively higher education and health system. ”

However, despite its ‘planning’ for the burgeoning population and infrastructure to cater to them, the city is crumbling under the pressure of its rapid urbanisation. The sheer population number along with the nature of development has had many impacts on the city’s health. It is widely understood that rapid and unplanned urban growth is often associated with a range of urban health hazards and associated health risks: substandard housing, crowding, air pollution, insufficient or contaminated drinking water, inadequate sanitation and solid waste disposal services, vector-borne diseases, industrial waste, increased motor vehicle traffic, stress associated with poverty and unemployment, among others (Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 2008). Each of these continues to be an issue in Delhi today.

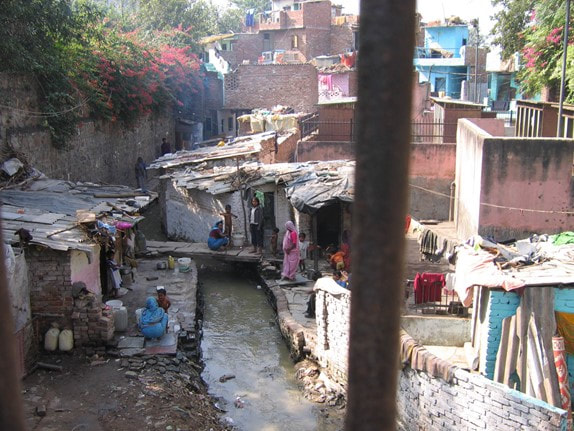

To begin with in terms of accommodating the in-migrants, the city faces a huge shortfall of housing stock. As per the note filed by the city’s civic bodies in 2012, 49% of the the total population of Delhi lives in slum areas, “unauthorized colonies" and about 860 jhuggi-jhonpri clusters with 4,20,000 jhuggies without any civic amenities (Times of India, 2012b). Most of these areas do not have electricity and water supply or sewerage, carry the maximum burden of diseases as well as social tensions, and their residents face fear of eviction. The MPD-2021 which projected Delhi’s population to reach 230 lakhs (23 million people) by 2021 aims at providing an additional of some 240 lakh dwelling units to house the existing slum population as well as the in-migrants through various strategies. The MPD further estimates that 50-55% of this housing requirement would be for urban poor in the form of houses of two rooms or less. However, little has been done to meet these targets. In 1962, Delhi had only 110 unauthorised colonies, built-in contravention of zoning regulations, where some two lakh people lived. This number rose to 1200 by 2017.

Health impacts of the growing population of Delhi

As per the decadal data of the Census of India, the population of Delhi has increased from 40.66 lakh (over 4 million) in 1971 to 138.5 lakh in 2001 (nearly 14 million). The in-migration during same period has increased from 8.76 lakh (800,760) in 1971 to 22.22 lakh (over 2 million) in 2001. The share of out-migration from Delhi has slightly increased from 2.42 lakh in 1961-71 to 4.58 lakh in 1991-2001. The net migrants (in-migrants – out-migrants) have steadily increased from 6.34 lakh during 1961-71 to 17.64 lakh during 1991-2001. (National Capital Regional Planning Board, 2001). In 2016 the population of Delhi grew by nearly 1,000 a day, of which over 300 were migrants who came to the city to settle down. The share of migrants in the capital’s population growth thus reached 33% in 2016 — highest in 15 years (Times of India, 2018). Delhi therefore, also got the tag of the ‘Migrant Capital’ of India owing to the large number of service sector jobs it offers along with the highest per capita income among states. A senior Urbanist states: "Delhi concentrates much more on wealth, resources, infrastructure and quality of urban services than other metros. The national capital offers a relatively higher education and health system. ”

However, despite its ‘planning’ for the burgeoning population and infrastructure to cater to them, the city is crumbling under the pressure of its rapid urbanisation. The sheer population number along with the nature of development has had many impacts on the city’s health. It is widely understood that rapid and unplanned urban growth is often associated with a range of urban health hazards and associated health risks: substandard housing, crowding, air pollution, insufficient or contaminated drinking water, inadequate sanitation and solid waste disposal services, vector-borne diseases, industrial waste, increased motor vehicle traffic, stress associated with poverty and unemployment, among others (Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 2008). Each of these continues to be an issue in Delhi today.

To begin with in terms of accommodating the in-migrants, the city faces a huge shortfall of housing stock. As per the note filed by the city’s civic bodies in 2012, 49% of the the total population of Delhi lives in slum areas, “unauthorized colonies" and about 860 jhuggi-jhonpri clusters with 4,20,000 jhuggies without any civic amenities (Times of India, 2012b). Most of these areas do not have electricity and water supply or sewerage, carry the maximum burden of diseases as well as social tensions, and their residents face fear of eviction. The MPD-2021 which projected Delhi’s population to reach 230 lakhs (23 million people) by 2021 aims at providing an additional of some 240 lakh dwelling units to house the existing slum population as well as the in-migrants through various strategies. The MPD further estimates that 50-55% of this housing requirement would be for urban poor in the form of houses of two rooms or less. However, little has been done to meet these targets. In 1962, Delhi had only 110 unauthorised colonies, built-in contravention of zoning regulations, where some two lakh people lived. This number rose to 1200 by 2017.

Figure 3: Slums of Delhi. Photos: Author

This rapid pace of Delhi’s urbanisation has had a huge impact on the city’s physical and social environment and consequently the mental health of its inhabitants. It has been well established that some children and adolescents in socioeconomically deprived urban areas may be drawn to antisocial behaviour. Although not exclusively an urban phenomenon, it thrives in inner cities where degradation, poverty, drug use, and unemployment result in an explosive blend favouring violent solutions (Lund and Cois, 2018). With half of the city’s population living in unplanned areas, it is no surprise that Delhi sees high rates of crime.

The range of disorders and deviancies associated with urbanisation is enormous and includes psychoses, depression, sociopathy, substance abuse, alcoholism, crime, delinquency, vandalism, family disintegration, and alienation (Trivedi et al, 2008). Chronic difficulties such as poor, overcrowded physical environments, high levels of violence and accidents, insecure tenure, and poor housing have all been shown to be associated with depression. Depression has strongly been associated with poverty and deprivation in low-and-middle-income countries (LMIC) based on both social causation theory and social drift theory (Lund and Cois, 2018). The social causation hypothesis proposes that the adverse social and economic conditions of poverty (such as financial stress increased exposure to income insecurity and reduced resources to protect individuals from the consequences of adverse life events) increase risk for mental illness. Conversely, the social selection/drift hypothesis proposes that people living with mental illness drift into poverty during the course of their lives due to disability, reduced economic productivity, increased stigma and increased health expenditure caused by their illness. The transition from rural culture to urban culture is one of the major stressors (Srivastava, 2009). The in-migrants need to acculturate and adapt not only to a new challenging urban environment, but also to alternative systems of symbols, meanings, and traditions (Trivedi et al, 2008).

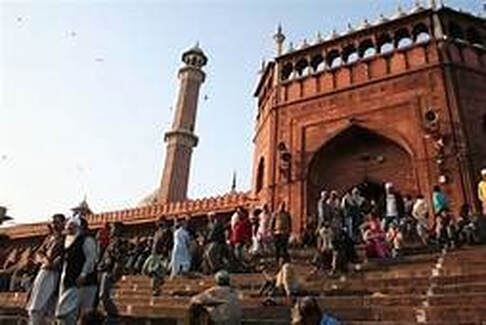

The migrants to Delhi have had to deal with a diverse range of stresses caused by both the lack of infrastructure provision and also the meanings and power notions associated with these facilities. One of the meanings and symbolism that is apparent in Delhi’s urban fabric is that of Power. As mentioned earlier, historically Delhi has been the political capital of many empires. The pre-British cities discussed power and grandeur while responding to the ecological setting and ensuring a connect with nature for all. The natural elements - sun, wind, earth, sky, moon; all played a important role in design of public spaces. Take the case of Chandni Chowk- the main market street of Shahajahanabad connecting the Palace Red Fort to the Fatehpuri Masjid. The city fabric- the layout of streets and public places responded to the ecological setting, terrain, its location along River Yamuna and the trade link (the Silk Route). The settlements followed an organic growth pattern.

British influence on urban planning and design in Delhi

With New Delhi, the British capital designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, the Garden City concepts were introduced. The use of geometry (a hexagonal grid) while laying out roads was also intended to impose their superiority and reinforce power and control of the British over the Indian sub-continent as a reaction to the Revolt of 1857. While there was an attempt to ensure continuity between the Central Ridge and River Yamuna by creating Central Vista (Rajpath) as a landscaped stretch, the avenues and roads were kept extremely wide to create a majestic feeling. The layout also incorporates generous green space, watercourses and the integration of trees and flowerbeds into the existing landscape in response to climate and dust. Visual connectivity was integral to the urban design scheme. Rajpath with the Rashtrapati Bhawan and the India Gate at its two ends has tremendous visual quality. Even the Parliament House and Connaught Place were visually linked to Jama Masjid. But in practice the imperial powers chose to look away from the locals and keep them restricted to their old areas away from the new capital.

The range of disorders and deviancies associated with urbanisation is enormous and includes psychoses, depression, sociopathy, substance abuse, alcoholism, crime, delinquency, vandalism, family disintegration, and alienation (Trivedi et al, 2008). Chronic difficulties such as poor, overcrowded physical environments, high levels of violence and accidents, insecure tenure, and poor housing have all been shown to be associated with depression. Depression has strongly been associated with poverty and deprivation in low-and-middle-income countries (LMIC) based on both social causation theory and social drift theory (Lund and Cois, 2018). The social causation hypothesis proposes that the adverse social and economic conditions of poverty (such as financial stress increased exposure to income insecurity and reduced resources to protect individuals from the consequences of adverse life events) increase risk for mental illness. Conversely, the social selection/drift hypothesis proposes that people living with mental illness drift into poverty during the course of their lives due to disability, reduced economic productivity, increased stigma and increased health expenditure caused by their illness. The transition from rural culture to urban culture is one of the major stressors (Srivastava, 2009). The in-migrants need to acculturate and adapt not only to a new challenging urban environment, but also to alternative systems of symbols, meanings, and traditions (Trivedi et al, 2008).

The migrants to Delhi have had to deal with a diverse range of stresses caused by both the lack of infrastructure provision and also the meanings and power notions associated with these facilities. One of the meanings and symbolism that is apparent in Delhi’s urban fabric is that of Power. As mentioned earlier, historically Delhi has been the political capital of many empires. The pre-British cities discussed power and grandeur while responding to the ecological setting and ensuring a connect with nature for all. The natural elements - sun, wind, earth, sky, moon; all played a important role in design of public spaces. Take the case of Chandni Chowk- the main market street of Shahajahanabad connecting the Palace Red Fort to the Fatehpuri Masjid. The city fabric- the layout of streets and public places responded to the ecological setting, terrain, its location along River Yamuna and the trade link (the Silk Route). The settlements followed an organic growth pattern.

British influence on urban planning and design in Delhi

With New Delhi, the British capital designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, the Garden City concepts were introduced. The use of geometry (a hexagonal grid) while laying out roads was also intended to impose their superiority and reinforce power and control of the British over the Indian sub-continent as a reaction to the Revolt of 1857. While there was an attempt to ensure continuity between the Central Ridge and River Yamuna by creating Central Vista (Rajpath) as a landscaped stretch, the avenues and roads were kept extremely wide to create a majestic feeling. The layout also incorporates generous green space, watercourses and the integration of trees and flowerbeds into the existing landscape in response to climate and dust. Visual connectivity was integral to the urban design scheme. Rajpath with the Rashtrapati Bhawan and the India Gate at its two ends has tremendous visual quality. Even the Parliament House and Connaught Place were visually linked to Jama Masjid. But in practice the imperial powers chose to look away from the locals and keep them restricted to their old areas away from the new capital.

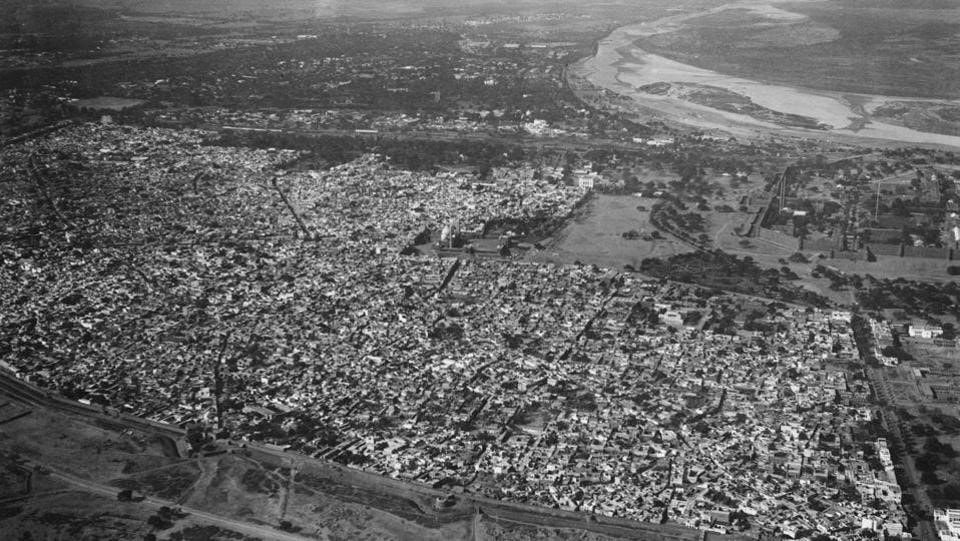

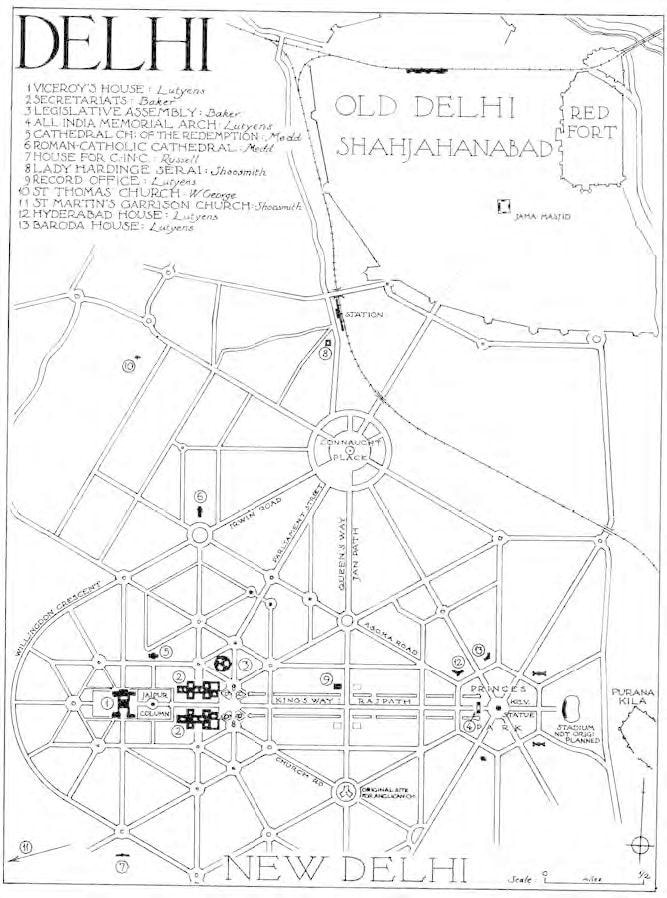

Figure 4a: Aerial View of Shahajahanabad looking east towards River Yamuna. 4b: Aerial view of New Delhi. Seen here are North & South Blocks along with the Parliament House in the background. 5c: Old Map of Delhi showing New Delhi and its location with the old city of Shahajahanabad.

'Along with the use of geometry to display power, the Britishers introduced a new building typology in the urban fabric - of ‘an object in space’ i.e. the street edge not being defined by the built mass but rather a boundary wall along the plot line. The building was located away from the plot edge and “setbacks” were left. Today, we continue to built using this typology and the boundary walls are getting higher and higher. This has not only broken the permeable relation between public and private domains but also resulted in the urban experience being defined by a blank wall. Anonymity and territorialisation enhanced by urban design. Thus the power play the Britishers introduced has continued to inform the planning and urban design of the city even today in many ways.

During the National Emergency between 1975-77, the city witnessed evictions, the most gruesome being the Turkman Gate Massacre when an estimated 7,00,000 people were displaced from slums and commercial properties over a period of 21 months, including large areas of the old city as part of a plan to ‘beautify’ Delhi (Homegrown, 2017). It is claimed that 400 people were killed to meet the political leaders' desire and whim to build a ‘Sanjay Minar’ (Minar is Hindi word for Tower) and for a shortcut or a wish to enjoy a clear view of India Gate from the Jama Masjid. This was not a new idea as Lutyens had in his original plan oriented the Rashtrapati Bhawan to look down the ceremonial avenue to the back of Jama Masjid (Liddle, 2018). The city oscillates between evictions and fantasies, all powered by urban design.

Residents in 'unauthorised colonies'

As mentioned earlier, today still almost half of the city’s population lives in slums and ‘unauthorised areas’ despite Delhi being the first city in the country to have a Master Plan and subsequent plans. This is indicative of not just faulty planning and implementation but also of an attitude of indifference to the incoming population. By referring to these in-migrants (who are forced to occupy vacant land in the absence of proper housing) as ‘unauthorised’ in itself involves power play. These people live with the fear of eviction regardless of the decades they have lived in that area and money invested in developing the neighbourhood level facilities and their own houses. Analyses suggest that at least 218 evictions have occurred between 1990 and 2007 in the capital, displacing 64,910 households of which only 52% have been re-settled (Bhan, Gautam and Shivanand, Swathi, 2013). These figures include the evictions carried out as part of preparation for the 2010 Commonwealth Games hosted by Delhi. While evictions are in themselves violent, the nature of evictions has changed with the poor getting peripheralised post-1990. Most resettlement sites pre-1990s were situated at the urban borders of the MPD-1962, while those post-1990s are situated at the edge of the urban plan boundaries of the MPD-2001. Some resettlement colonies created after 2000, remain outside even the urban boundaries of the latest MPD-2021. This marginalisation and hostility builds feeling of distrust and anger amongst those evicted adding to the city’s woes.

However, recently in November 2019, the government passed the National Capital Territory of Delhi (Recognition of Property Rights of Residents in Unauthorised Colonies) Bill-2019 aimed at granting ownership rights to over eight lakh (800,000) people living in 1,731 ‘illegal’ colonies. DDA has already delineated boundaries of 1,300 such colonies. While this is starting to get implemented, a senior Urbanist and Professor of Urban Design emphasises on the need for this to be followed up with very strong commitments towards improving the physical quality of the living environment. Else it would remain a good scheme on paper and be an extension of colonial mindset of keeping the weaker sections of the society at the margins.

Also, this colonial mindset is not just towards the in-migrants to the city. The Zonal Plans prepared under MPD-2021 for the sub-cities of Dwarka and Rohini do not take into account the existing urbanised villages. These sub-cities are being developed by urbanising the agricultural land on the periphery of the city. A standard pre-designed ‘sector’ layout has been repeatedly copy-pasted onto the available land based on the number of people that need to be accommodated. These sectors are designed to be ‘self-sufficient’ units catering to all the needs of the residents. This notion of a typical ‘self-sufficient sector’ though a misnomer in itself is also responsible for less social interactions and isolation in the city. With more and more people coming into the city, the feeling of anonymity is on the rise. As a senior Architect-Urbanist notes: “People are moving into Delhi very rapidly causing a social tension between the long-term residents and the short-term residents on account of distrust, fear and increased anonymity. This has led to social disconnect and isolation in the city.” The notions of “self-sufficiency” further breed the ideas of “An Anonymous Self” as separate from the larger “Cohesive Community”.

But while planning divides us, its failure as manifested in health issues unites us.

During the National Emergency between 1975-77, the city witnessed evictions, the most gruesome being the Turkman Gate Massacre when an estimated 7,00,000 people were displaced from slums and commercial properties over a period of 21 months, including large areas of the old city as part of a plan to ‘beautify’ Delhi (Homegrown, 2017). It is claimed that 400 people were killed to meet the political leaders' desire and whim to build a ‘Sanjay Minar’ (Minar is Hindi word for Tower) and for a shortcut or a wish to enjoy a clear view of India Gate from the Jama Masjid. This was not a new idea as Lutyens had in his original plan oriented the Rashtrapati Bhawan to look down the ceremonial avenue to the back of Jama Masjid (Liddle, 2018). The city oscillates between evictions and fantasies, all powered by urban design.

Residents in 'unauthorised colonies'

As mentioned earlier, today still almost half of the city’s population lives in slums and ‘unauthorised areas’ despite Delhi being the first city in the country to have a Master Plan and subsequent plans. This is indicative of not just faulty planning and implementation but also of an attitude of indifference to the incoming population. By referring to these in-migrants (who are forced to occupy vacant land in the absence of proper housing) as ‘unauthorised’ in itself involves power play. These people live with the fear of eviction regardless of the decades they have lived in that area and money invested in developing the neighbourhood level facilities and their own houses. Analyses suggest that at least 218 evictions have occurred between 1990 and 2007 in the capital, displacing 64,910 households of which only 52% have been re-settled (Bhan, Gautam and Shivanand, Swathi, 2013). These figures include the evictions carried out as part of preparation for the 2010 Commonwealth Games hosted by Delhi. While evictions are in themselves violent, the nature of evictions has changed with the poor getting peripheralised post-1990. Most resettlement sites pre-1990s were situated at the urban borders of the MPD-1962, while those post-1990s are situated at the edge of the urban plan boundaries of the MPD-2001. Some resettlement colonies created after 2000, remain outside even the urban boundaries of the latest MPD-2021. This marginalisation and hostility builds feeling of distrust and anger amongst those evicted adding to the city’s woes.

However, recently in November 2019, the government passed the National Capital Territory of Delhi (Recognition of Property Rights of Residents in Unauthorised Colonies) Bill-2019 aimed at granting ownership rights to over eight lakh (800,000) people living in 1,731 ‘illegal’ colonies. DDA has already delineated boundaries of 1,300 such colonies. While this is starting to get implemented, a senior Urbanist and Professor of Urban Design emphasises on the need for this to be followed up with very strong commitments towards improving the physical quality of the living environment. Else it would remain a good scheme on paper and be an extension of colonial mindset of keeping the weaker sections of the society at the margins.

Also, this colonial mindset is not just towards the in-migrants to the city. The Zonal Plans prepared under MPD-2021 for the sub-cities of Dwarka and Rohini do not take into account the existing urbanised villages. These sub-cities are being developed by urbanising the agricultural land on the periphery of the city. A standard pre-designed ‘sector’ layout has been repeatedly copy-pasted onto the available land based on the number of people that need to be accommodated. These sectors are designed to be ‘self-sufficient’ units catering to all the needs of the residents. This notion of a typical ‘self-sufficient sector’ though a misnomer in itself is also responsible for less social interactions and isolation in the city. With more and more people coming into the city, the feeling of anonymity is on the rise. As a senior Architect-Urbanist notes: “People are moving into Delhi very rapidly causing a social tension between the long-term residents and the short-term residents on account of distrust, fear and increased anonymity. This has led to social disconnect and isolation in the city.” The notions of “self-sufficiency” further breed the ideas of “An Anonymous Self” as separate from the larger “Cohesive Community”.

But while planning divides us, its failure as manifested in health issues unites us.

Health priorities in Delhi: Most Polluted City

The discussion on health in Delhi’s context currently focuses on affects of air pollution with Delhi being declared the most polluted city in the world by WHO reports. The Air Quality continues to be very poor with high concentrations of PM10 and PM2.5. Delhi has a PM2.5 rating of 153 micrograms, which represents an “unhealthy air quality” that causes “increased respiratory effects in general population” (Times of India, 2014). Besides the loss in productivity and added health expenditure, higher level of air pollution are found to be associated with lower levels of happiness (The Economic Times, 2019). According to the study published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour for the city of Beijing, the issues and findings cited resonate with the situation in Delhi. Zheng says, “Pollution also has an emotional cost. People are unhappy, and that means they may make irrational decisions. On polluted days, people have been shown to be more likely to engage in impulsive and risky behaviour that they may later regret, possibly as a result of short-term depression and anxiety.” Of note, Delhites have a reputation within India for being aggressive.

The city experiencing rapid urbanisation has a large amount of construction activity ongoing including that of construction of new metro corridors. All these activities add dust, soot, cement, wood dust etc to the atmosphere. In addition to this, factories in and on the outskirts of Delhi release toxic chemicals that contaminate the air. A study by Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in 2013 showed that industries and thermal power plants contribute to 29 percent of the total air pollution in Delhi (Times of India, 2014). Vehicular emissions contribute to 63% of the city’s air pollution. Introduction of CNG-fuelled vehicles at the beginning of the century had “cleaned the city’s air”, but statistics show that Delhi’s pollution has increased five times over the past eight years. Today, Delhi is a city of cars (or private vehicles). The city boasts of one of the largest road networks in India i.e. 2,103 km/100km.sq. In 2008, there were 5.5 million vehicles in Delhi, the largest number in any world city. Nearly 1,000 more are added on a daily basis (Sahai SN, 2009). Interestingly, only 25% of the city’s population owns these private vehicles (cars/two-wheelers). (How to Decongest Delhi).

Since the main source of air pollution is vehicular emissions, reducing these is the most urgent and important next step. In January 2019, the GoI launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) that aims to reduce toxic particulate matter in 102 cities by 2024, taking 2017 as the base year. The NCAP is a mid-term, five-year action plan that includes collaborative, multi-scale and cross-sectoral coordination between relevant Central ministries, state governments and local bodies; and forming city-specific-action-plans (India Today, 2019). In December 2019, the Delhi government approved the Delhi Electric Vehicle Policy-2019 with the primary goal to improve Delhi’s air quality by bringing down emissions from the transport sector. This policy will seek to drive rapid adoption of Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) such that they contribute to 25% of all new vehicle registrations by 2024 (The Economic Times, 2019b). This policy focuses on bringing down emissions by shifting from a petrol/diesel/CNG as fuel to using solar energy. However, this does not aim to reduce the number of vehicles on the road causing congestion. To effectively solve transportation issues and solve the environmental issues one needs to study these in the context of Delhi’s urban planning and development over the years which has lead to this crisis.

Other aspects of transportation affecting mental health in Delhi

The MPD-1962 defined Delhi’s growth as a poly-nodal city with the major city level public institutions, universities and colleges, hospitals and work centres located along arterial ring roads connecting the entire city. Thus the Ring Road and Outer Ring Road were developed and a dedicated bus route operated on these. This was the ‘transit oriented development’ model of the 1960’s. With the formulation of NCR in 1985, more nodes of opportunity came up outside the boundary of Delhi. People started to commute long distances for education and employment. These long commutes have also resulted in people having less time to spend with family and for leisure; along with more air pollution, more vehicular congestion and traffic jams. This have led to the expansion of road infrastructure as well as public transportation network mainly the Delhi Metro. However the public transportation’s expansion has failed to keep pace with the development of NCR and the opportunities being offered. Even within the city, the public bus system has failed to connect efficiently and comfortably. Besides these people mostly walk, cycle and use para-transit facilities like autos, cycle-rickshaws, shared autos, e-rickshaws. As per the report on How to Decongest Delhi about 35% of the city walks, 27% uses buses and 7% uses autos/cycle-rickshaws.

The MPD-2021 envisages an Integrated Multi-Modal Transport System interlinking Metro Rail, Ring Rail, Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS), Intermediate Passenger Transport (IPT) along with making roads friendly for pedestrians, differently-abled and cyclists. However, the city has continued to cater more to users of private vehicles. In 2010, the Delhi government had undertaken a study “Transport Demand Forecast Study and Development of an Integrated Road Cum Multi-Modal Public Transport Network for NCT of Delhi” to cater to the public transport demand up to 2021. The study recommended building additional 149kms of metro rail, 40kms of light metro, 365.5kms of Bus Rapid Transit corridor (BRT) for inner city movement; and dedicated commuter rail service between Delhi and neighbouring NCR towns. Even then the projected modal share of public transport system just reached 50%.

Buses

Public transport continues to be less-preferred for two main reasons: a) lack of comfort and b) lack of safety. The poor and irregular frequency, long waiting time, uncomfortable waits often without shade, makes it uncomfortable especially for elderly people, women, expecting mothers and adults with kids. Surveys have revealed that the travel patterns of women are different from men. Women make numerous trips of short distances therefore relying more on buses and para-transit facilities. But the city faces a huge shortfall in the number of buses on road: only 5,554 buses (against the required number of 11,000 vehicles) (Devdiscourse, 2018). Currently there are 1,275 low floor AC buses, 2,506 low floor non-AC buses and 101 Green standard floor non-AC buses and 1,672 orange colour standard low floor buses operating in the city. These were introduced at the time of constructing a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridor in the city with the intention of developing a city-wide network of such corridors. In 2008, the first (& only in the city) BRT corridor became operational along a north-south arterial road. But sadly due to design flaws, implementation issues and political reasons the corridor was scraped off in 2016. Besides these the city hasn’t seen any major initiative towards increasing its modal share of buses. New bus stops were built in some parts of the city to be disabled-friendly, have signages for information on bus routes, be will-lit at night, and have better seating. Sadly these bus stops too failed as they were built either with a high kerb height, or obstructing the footpath or without any tactile paving for the visually impaired. In March 2019 the Delhi government approved the procurement of 1,000 electric buses as a push to combat air pollution. As per their guidelines, these buses would be equipped with with CCTV, Automatic Vehicle Tracking System (AVTS), panic buttons and panic alarms. Along with these the government is also planning to add more low-floor CNG buses to take the total number of buses plying in the city to 9,500 by May 2020.

However, while these new buses are being procured, the poor management of bus operation and the poor frequency of buses and therefore over-crowding, has resulted in making it a less preferred mode of travel.

The discussion on health in Delhi’s context currently focuses on affects of air pollution with Delhi being declared the most polluted city in the world by WHO reports. The Air Quality continues to be very poor with high concentrations of PM10 and PM2.5. Delhi has a PM2.5 rating of 153 micrograms, which represents an “unhealthy air quality” that causes “increased respiratory effects in general population” (Times of India, 2014). Besides the loss in productivity and added health expenditure, higher level of air pollution are found to be associated with lower levels of happiness (The Economic Times, 2019). According to the study published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour for the city of Beijing, the issues and findings cited resonate with the situation in Delhi. Zheng says, “Pollution also has an emotional cost. People are unhappy, and that means they may make irrational decisions. On polluted days, people have been shown to be more likely to engage in impulsive and risky behaviour that they may later regret, possibly as a result of short-term depression and anxiety.” Of note, Delhites have a reputation within India for being aggressive.

The city experiencing rapid urbanisation has a large amount of construction activity ongoing including that of construction of new metro corridors. All these activities add dust, soot, cement, wood dust etc to the atmosphere. In addition to this, factories in and on the outskirts of Delhi release toxic chemicals that contaminate the air. A study by Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in 2013 showed that industries and thermal power plants contribute to 29 percent of the total air pollution in Delhi (Times of India, 2014). Vehicular emissions contribute to 63% of the city’s air pollution. Introduction of CNG-fuelled vehicles at the beginning of the century had “cleaned the city’s air”, but statistics show that Delhi’s pollution has increased five times over the past eight years. Today, Delhi is a city of cars (or private vehicles). The city boasts of one of the largest road networks in India i.e. 2,103 km/100km.sq. In 2008, there were 5.5 million vehicles in Delhi, the largest number in any world city. Nearly 1,000 more are added on a daily basis (Sahai SN, 2009). Interestingly, only 25% of the city’s population owns these private vehicles (cars/two-wheelers). (How to Decongest Delhi).

Since the main source of air pollution is vehicular emissions, reducing these is the most urgent and important next step. In January 2019, the GoI launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) that aims to reduce toxic particulate matter in 102 cities by 2024, taking 2017 as the base year. The NCAP is a mid-term, five-year action plan that includes collaborative, multi-scale and cross-sectoral coordination between relevant Central ministries, state governments and local bodies; and forming city-specific-action-plans (India Today, 2019). In December 2019, the Delhi government approved the Delhi Electric Vehicle Policy-2019 with the primary goal to improve Delhi’s air quality by bringing down emissions from the transport sector. This policy will seek to drive rapid adoption of Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) such that they contribute to 25% of all new vehicle registrations by 2024 (The Economic Times, 2019b). This policy focuses on bringing down emissions by shifting from a petrol/diesel/CNG as fuel to using solar energy. However, this does not aim to reduce the number of vehicles on the road causing congestion. To effectively solve transportation issues and solve the environmental issues one needs to study these in the context of Delhi’s urban planning and development over the years which has lead to this crisis.

Other aspects of transportation affecting mental health in Delhi

The MPD-1962 defined Delhi’s growth as a poly-nodal city with the major city level public institutions, universities and colleges, hospitals and work centres located along arterial ring roads connecting the entire city. Thus the Ring Road and Outer Ring Road were developed and a dedicated bus route operated on these. This was the ‘transit oriented development’ model of the 1960’s. With the formulation of NCR in 1985, more nodes of opportunity came up outside the boundary of Delhi. People started to commute long distances for education and employment. These long commutes have also resulted in people having less time to spend with family and for leisure; along with more air pollution, more vehicular congestion and traffic jams. This have led to the expansion of road infrastructure as well as public transportation network mainly the Delhi Metro. However the public transportation’s expansion has failed to keep pace with the development of NCR and the opportunities being offered. Even within the city, the public bus system has failed to connect efficiently and comfortably. Besides these people mostly walk, cycle and use para-transit facilities like autos, cycle-rickshaws, shared autos, e-rickshaws. As per the report on How to Decongest Delhi about 35% of the city walks, 27% uses buses and 7% uses autos/cycle-rickshaws.

The MPD-2021 envisages an Integrated Multi-Modal Transport System interlinking Metro Rail, Ring Rail, Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS), Intermediate Passenger Transport (IPT) along with making roads friendly for pedestrians, differently-abled and cyclists. However, the city has continued to cater more to users of private vehicles. In 2010, the Delhi government had undertaken a study “Transport Demand Forecast Study and Development of an Integrated Road Cum Multi-Modal Public Transport Network for NCT of Delhi” to cater to the public transport demand up to 2021. The study recommended building additional 149kms of metro rail, 40kms of light metro, 365.5kms of Bus Rapid Transit corridor (BRT) for inner city movement; and dedicated commuter rail service between Delhi and neighbouring NCR towns. Even then the projected modal share of public transport system just reached 50%.

Buses

Public transport continues to be less-preferred for two main reasons: a) lack of comfort and b) lack of safety. The poor and irregular frequency, long waiting time, uncomfortable waits often without shade, makes it uncomfortable especially for elderly people, women, expecting mothers and adults with kids. Surveys have revealed that the travel patterns of women are different from men. Women make numerous trips of short distances therefore relying more on buses and para-transit facilities. But the city faces a huge shortfall in the number of buses on road: only 5,554 buses (against the required number of 11,000 vehicles) (Devdiscourse, 2018). Currently there are 1,275 low floor AC buses, 2,506 low floor non-AC buses and 101 Green standard floor non-AC buses and 1,672 orange colour standard low floor buses operating in the city. These were introduced at the time of constructing a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridor in the city with the intention of developing a city-wide network of such corridors. In 2008, the first (& only in the city) BRT corridor became operational along a north-south arterial road. But sadly due to design flaws, implementation issues and political reasons the corridor was scraped off in 2016. Besides these the city hasn’t seen any major initiative towards increasing its modal share of buses. New bus stops were built in some parts of the city to be disabled-friendly, have signages for information on bus routes, be will-lit at night, and have better seating. Sadly these bus stops too failed as they were built either with a high kerb height, or obstructing the footpath or without any tactile paving for the visually impaired. In March 2019 the Delhi government approved the procurement of 1,000 electric buses as a push to combat air pollution. As per their guidelines, these buses would be equipped with with CCTV, Automatic Vehicle Tracking System (AVTS), panic buttons and panic alarms. Along with these the government is also planning to add more low-floor CNG buses to take the total number of buses plying in the city to 9,500 by May 2020.

However, while these new buses are being procured, the poor management of bus operation and the poor frequency of buses and therefore over-crowding, has resulted in making it a less preferred mode of travel.

Figure 5a: A typical bus stand with limited seating and located on high footpath. 5b: Delhi’s BRT Corridor before it was dismantled.

In fact, the lack of adherence to a schedule has lead to ‘waiting anxiety’ amongst passengers who remain uncertain about the time of bus arrival. One evidence of this ‘waiting anxiety’ is to see passengers spilling out on the road because their numbers have increased to unacceptable levels and they are anxious to board the bus faster than fellow travellers in order to bag a seat (Sahai, 2009). This also causes people to rush-and-push to board, adding to the aggression and hostility characteristic of Delhi’s public realm. Overcrowding is also one of the main facilitators of sexual harassment in buses.

Public transport in Delhi in general continues to be unsafe for women. Crimes have been committed on metro stations despite full CCTV coverage, in buses, on bus-stops, in autos and cabs; as well as while walking on the street in broad daylight. Which is why it came as no surprise that women-driven private vehicles were exempted during the odd-even scheme of the Delhi government in 2016 which was aimed at reducing vehicular pollution in the city. Sexual harassment is a ‘normalised’ part of a woman’s commute in Delhi. A survey conducted with female students revealed that over 89% had faced some form of harassment while traveling in the city, 63% of female students have experienced unwanted staring, 50% have received inappropriate comments, 40% have been touched, groped, or grabbed and 26% have been followed (Borker, 2018). Various research studies have shown that, an unsafe situation or crime encountered by a user would create great psychological fear resulting in reduced/no usage of public transport system at all. Fear of crime is thus widely recognised as a barrier to public transport use.

Underground and overground

It has been two decades since the foundation for the Delhi Metro was laid and the city’s air quality and sense of safety both have deteriorated. Today, the Delhi Metro is by far the largest and busiest metro in India, and is the world's 8th longest metro system and 16th largest by ridership running 389 kilometres serving 285 stations. The first Metro became operational in 2002 after being in planning from 1995.

While the metro was being planned during the same period, Delhi also built clover-leaf flyovers along its main arterial roads. The Okhla flyover was built along the Outer Ring Road and the AIIMS flyover along the Ring Road to “ease” traffic snarls. Thus began the city’s obsession with “non-stop high-speed” movement. While in 1982 (pre-NCRBA) the city had just five flyovers, it presently has 90 (of these 25 were built in the last decade) which is why Delhi is rightly also referred to as the ‘City of Flyovers’ (Phukan, 2014). Now almost every intersection along the Ring Road and the Outer Ring Road has a simple or clover-leaf flyover. Of course, over the course of time none of them have been able to balance the rise in vehicles. Traffic jams continue to plague the city. Also, it is observed that the point of congestion only shifts to the next intersection but largely people continue to be stuck in traffic. According to a report made by IBM’s global Commuter Pain study in 2013, New Delhi is among the top 10 cities in the world having the worst traffic jams (Phukan, 2015).

Public transport in Delhi in general continues to be unsafe for women. Crimes have been committed on metro stations despite full CCTV coverage, in buses, on bus-stops, in autos and cabs; as well as while walking on the street in broad daylight. Which is why it came as no surprise that women-driven private vehicles were exempted during the odd-even scheme of the Delhi government in 2016 which was aimed at reducing vehicular pollution in the city. Sexual harassment is a ‘normalised’ part of a woman’s commute in Delhi. A survey conducted with female students revealed that over 89% had faced some form of harassment while traveling in the city, 63% of female students have experienced unwanted staring, 50% have received inappropriate comments, 40% have been touched, groped, or grabbed and 26% have been followed (Borker, 2018). Various research studies have shown that, an unsafe situation or crime encountered by a user would create great psychological fear resulting in reduced/no usage of public transport system at all. Fear of crime is thus widely recognised as a barrier to public transport use.

Underground and overground

It has been two decades since the foundation for the Delhi Metro was laid and the city’s air quality and sense of safety both have deteriorated. Today, the Delhi Metro is by far the largest and busiest metro in India, and is the world's 8th longest metro system and 16th largest by ridership running 389 kilometres serving 285 stations. The first Metro became operational in 2002 after being in planning from 1995.

While the metro was being planned during the same period, Delhi also built clover-leaf flyovers along its main arterial roads. The Okhla flyover was built along the Outer Ring Road and the AIIMS flyover along the Ring Road to “ease” traffic snarls. Thus began the city’s obsession with “non-stop high-speed” movement. While in 1982 (pre-NCRBA) the city had just five flyovers, it presently has 90 (of these 25 were built in the last decade) which is why Delhi is rightly also referred to as the ‘City of Flyovers’ (Phukan, 2014). Now almost every intersection along the Ring Road and the Outer Ring Road has a simple or clover-leaf flyover. Of course, over the course of time none of them have been able to balance the rise in vehicles. Traffic jams continue to plague the city. Also, it is observed that the point of congestion only shifts to the next intersection but largely people continue to be stuck in traffic. According to a report made by IBM’s global Commuter Pain study in 2013, New Delhi is among the top 10 cities in the world having the worst traffic jams (Phukan, 2015).

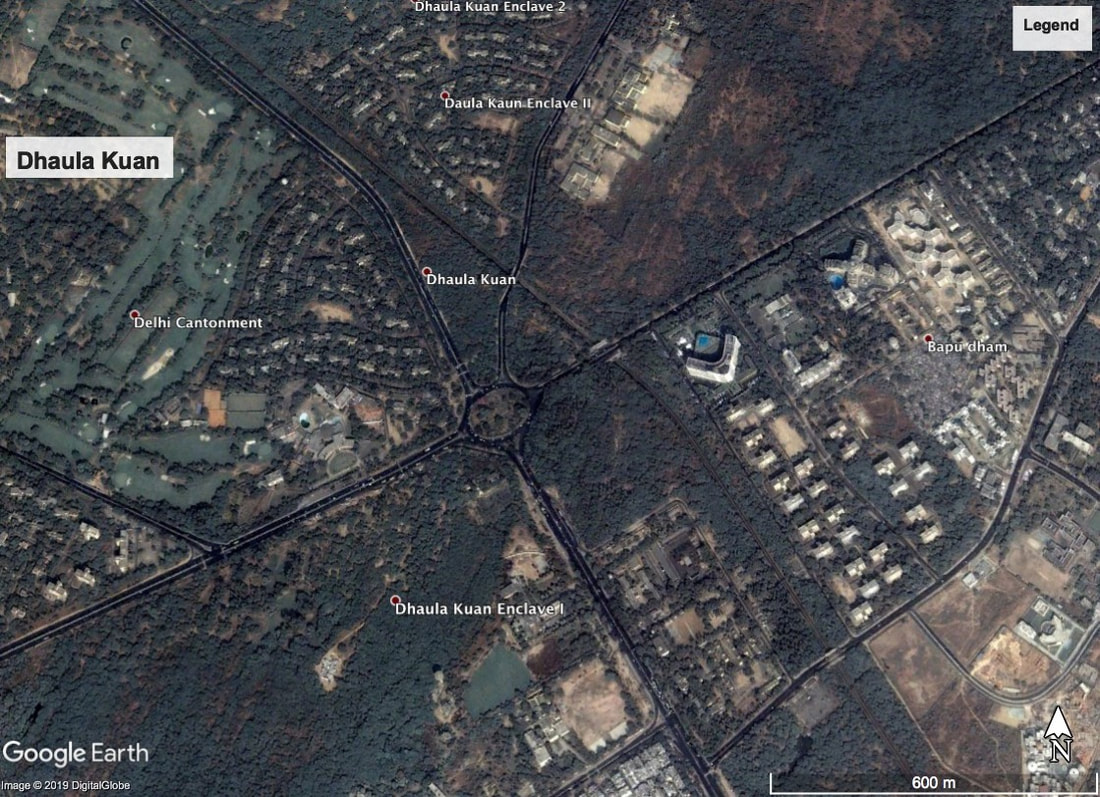

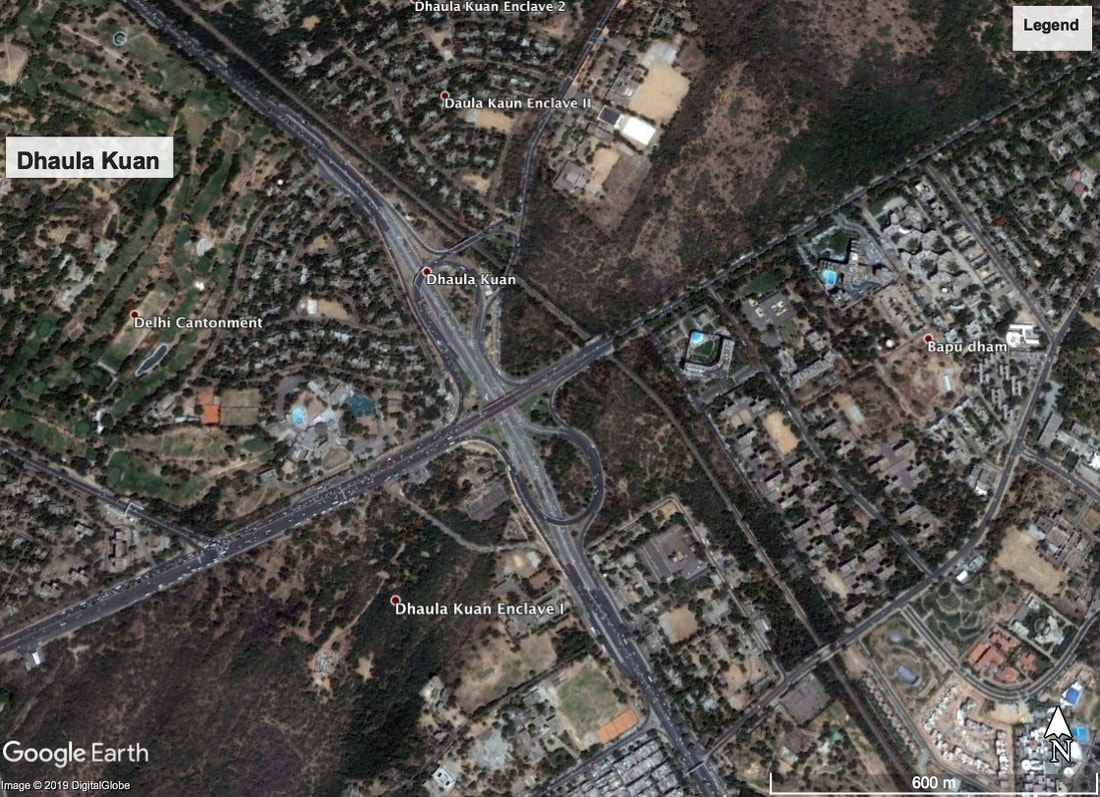

Figure 6: Google Earth images demonstrate the loss of tree cover associated with development of flyovers.

Also these flyovers have this ‘left-over’ space underneath them which has mostly been occupied by the homeless and destitute such as rickshaw pullers, ice-cream vendors, beggars and hawkers. At some locations, drug-addicts and vagabonds have made their homes while at other spots debris and garbage has been dumped (Hindustan Times, 2016). Experts suggest developing these as public places with diverse community activities. As these intersections have all become ‘signal-free’ they have added to the woes of pedestrians and cyclists needing to cross over. The story of clover-leaf flyovers is the most troublesome. Yet the city continues to build more and more flyovers with the latest plan to construct a double-decker flyover over one of the junctions. This proposal in itself proves that flyovers have failed in controlling traffic. And yet the city continues to plan more flyovers over existing ones.

The city fails to recognise that all that these flyovers have resulted in is a heightened lust for speed which in this author's assessment has matched the sex hunger of many. The city has seen many cases of abduction and rape along these flyovers as they facilitate one to grab-and-escape. The most serious is the Dhaula Kuan intersection where the number of crimes shot up after the flyover was built. Earlier this junction was a simple roundabout where traffic was forced to slow down. Then the extravagant clover-leaf flyover was built to ensure fast (read non-stop) vehicular movement.

It is no surprise that in the 2012 Delhi gang-rape case, the rape happened while the bus moved non-stop along the city’s main arterial roads. The case highlighted major safety issues with Delhi’s public transportation system like poor bus connectivity as well as lack of para-transit facilities especially in the off-peak hours of the day. With the city having an unsafe and unreliable public transportation system in place, a woman’s mobility and access to resources are limited preventing them from achieving their full potential. Indian women were found to be most stressed in the world according to 2011 Nielsen Report (add reference); men too are violent and aggressive.

Delhi is also a city infamous for Road Rage. Statistically the city ranks fourth at the National level when it comes to most “fuming drivers” as per 2015 statistics released by the National Crime Records Bureau (Autocar India, 2016). Delhi senior police officials have stated that in 2013, 36 road rage incidents were reported and in 2014 till August, there were already more than 20 cases registered. The PCR receives almost 10-12 calls every day on minor scuffles on the roads of Delhi. Psychologists note that crowding causes aggression. But crowding itself cannot be blamed for road rage if we compare India and China. China despite having more vehicles and higher population than Indian cities, saw half the number of road deaths than India. According to psychologists, the aggressive-driving behaviour shown by many drivers is associated with “intermittent explosive disorder” in medical terminology which can be caused from getting annoyed over small issues to feeling superior than others to getting violent. Sociologists point to a breakdown in community values, and psychologists talk about the "intoxicating" feeling of power and anonymity offered by a modern automobile and in case of Delhi by the city itself.

The city fails to recognise that all that these flyovers have resulted in is a heightened lust for speed which in this author's assessment has matched the sex hunger of many. The city has seen many cases of abduction and rape along these flyovers as they facilitate one to grab-and-escape. The most serious is the Dhaula Kuan intersection where the number of crimes shot up after the flyover was built. Earlier this junction was a simple roundabout where traffic was forced to slow down. Then the extravagant clover-leaf flyover was built to ensure fast (read non-stop) vehicular movement.

It is no surprise that in the 2012 Delhi gang-rape case, the rape happened while the bus moved non-stop along the city’s main arterial roads. The case highlighted major safety issues with Delhi’s public transportation system like poor bus connectivity as well as lack of para-transit facilities especially in the off-peak hours of the day. With the city having an unsafe and unreliable public transportation system in place, a woman’s mobility and access to resources are limited preventing them from achieving their full potential. Indian women were found to be most stressed in the world according to 2011 Nielsen Report (add reference); men too are violent and aggressive.

Delhi is also a city infamous for Road Rage. Statistically the city ranks fourth at the National level when it comes to most “fuming drivers” as per 2015 statistics released by the National Crime Records Bureau (Autocar India, 2016). Delhi senior police officials have stated that in 2013, 36 road rage incidents were reported and in 2014 till August, there were already more than 20 cases registered. The PCR receives almost 10-12 calls every day on minor scuffles on the roads of Delhi. Psychologists note that crowding causes aggression. But crowding itself cannot be blamed for road rage if we compare India and China. China despite having more vehicles and higher population than Indian cities, saw half the number of road deaths than India. According to psychologists, the aggressive-driving behaviour shown by many drivers is associated with “intermittent explosive disorder” in medical terminology which can be caused from getting annoyed over small issues to feeling superior than others to getting violent. Sociologists point to a breakdown in community values, and psychologists talk about the "intoxicating" feeling of power and anonymity offered by a modern automobile and in case of Delhi by the city itself.

Figure 7: News of Road Rage has become common in Delhi. Photo: from CNN.

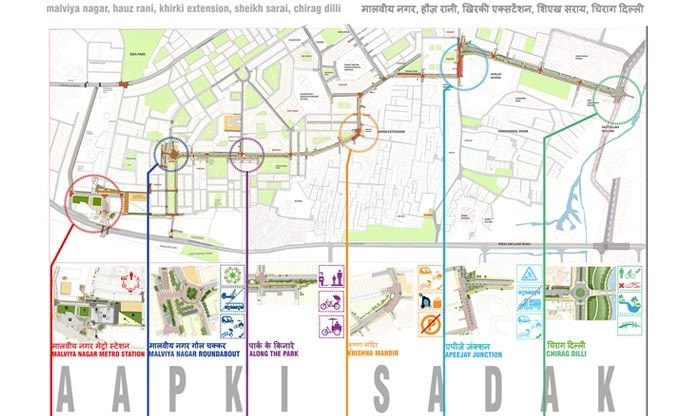

Pedestrians and cyclists in Delhi

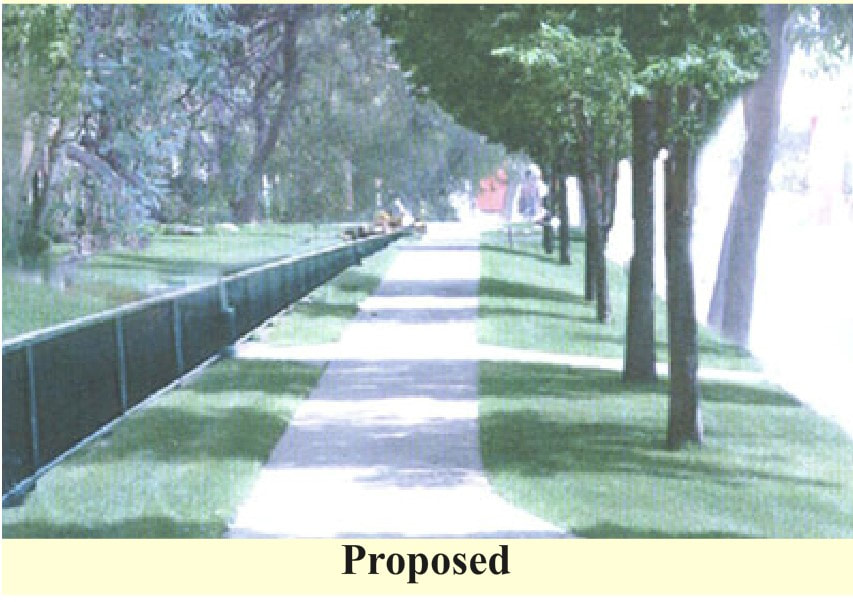

In Delhi everybody is in a hurry but confined to their cars stuck in a traffic jam. This is bound to be frustrating. But the situation is most frustrating for pedestrians and cyclists. An estimate by the Indian Road Congress (IRC) shows an average pedestrian in Delhi takes around seven to eight minutes to cross a busy intersection from end-to-end. (Hindustan Times, 2019).