Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2020:6;7 (Advance publication 2019)

|

CITY CASE STUDY

|

A Case Study of Urban Design for Wellbeing and Mental Health in Adelaide, Australia

Trish Hansen (1), Rachel Pfitzner (2), Carmel Williams (3), Beth Keough (3), Claudia Galicki (3), Heath Edwards (4), Sally Bolton (4), Gabrielle Kelly (5) and Kim Krebs (6)

(1) Urban Mind, Australia

(2) Department for Environment and Water, Government of South Australia

(3) Department Health and Wellbeing, Government of South Australia

(4) Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, South Australia

(5) Wellbeing and Resilience Centre, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI)

(6) Adelaide & Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board

(2) Department for Environment and Water, Government of South Australia

(3) Department Health and Wellbeing, Government of South Australia

(4) Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, South Australia

(5) Wellbeing and Resilience Centre, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI)

(6) Adelaide & Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board

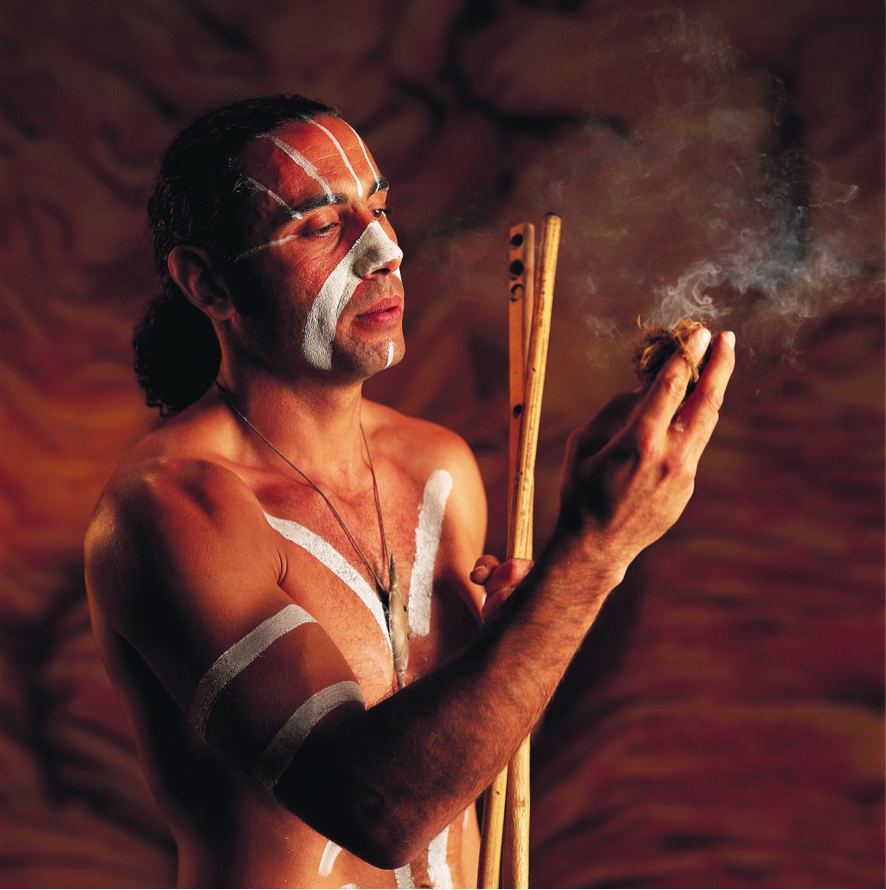

This work respectfully acknowledges all first nations of the state of South Australia and pays respect to the Spiritual Ancestors, Elders and Traditional Owners and Custodians, their customs, traditions, culture and in their protection and nurturing of this place; their tribal lands and waters.

Introduction

The purpose of this case study is to describe how Greater Adelaide, the capital city of the State of South Australia, applies the key principles of urban design for wellbeing and population mental health. It brings together the relevant history, current policy, as well as social and cultural context with the perspectives of local urban professionals, in an endeavour to provoke further discussion, collaboration and action in the endless pursuit to live meaningfully and sustainably.

The scope of this study is Greater Adelaide comprising the City of Adelaide municipality, as well as 26 inner city, metropolitan and regional municipalities.

Greater metropolitan Adelaide region as defined by the LGA SA comprising: Adelaide City Council, Adelaide Hills Council, Alexandrina Council, Barossa Council, City of Burnside, Campbelltown City Council, City of Charles Sturt, Town of Gawler, City of Holdfast Bay, Light Regional Council, Mallala District Council, City of Marion, City of Mitcham, Mount Barker District Council, Rural City of Murray Bridge, City of Norwood Payneham & St. Peters, City of Onkaparinga, City of Playford, City of Port Adelaide Enfield, City of Prospect, City of Salisbury, City of Tea Tree Gully, City of Unley, Victor Harbor Council, Town of Walkerville, City of West Torrens, District Council of Yankalilla. (1)

The scope of this study is Greater Adelaide comprising the City of Adelaide municipality, as well as 26 inner city, metropolitan and regional municipalities.

Greater metropolitan Adelaide region as defined by the LGA SA comprising: Adelaide City Council, Adelaide Hills Council, Alexandrina Council, Barossa Council, City of Burnside, Campbelltown City Council, City of Charles Sturt, Town of Gawler, City of Holdfast Bay, Light Regional Council, Mallala District Council, City of Marion, City of Mitcham, Mount Barker District Council, Rural City of Murray Bridge, City of Norwood Payneham & St. Peters, City of Onkaparinga, City of Playford, City of Port Adelaide Enfield, City of Prospect, City of Salisbury, City of Tea Tree Gully, City of Unley, Victor Harbor Council, Town of Walkerville, City of West Torrens, District Council of Yankalilla. (1)

Figure 1: Adelaide Oval, Image courtesy of the South Australian Tourism commission

Australia has three levels of Government or law making, comprising: Federal (or national) Parliament, which is based in Canberra, the nation’s capital city; state/territory Parliaments, in each state/territory capital city ;and local councils (also called shires or municipalities).

Urban design refers to the creation of the places people live - our suburbs, towns and cities. It determines the appearance, scale and ambience of a place, and is influenced by political, economic, environmental, social and cultural life.

The World Health Organisation defines mental health as a state of wellbeing in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to her or his community.

Urban design refers to the creation of the places people live - our suburbs, towns and cities. It determines the appearance, scale and ambience of a place, and is influenced by political, economic, environmental, social and cultural life.

The World Health Organisation defines mental health as a state of wellbeing in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to her or his community.

Figure 2: Adelaide, South Australia Map, Prepared by the Office for Design and Architecture South Australia

Method

Literature review

A search was conducted on South Australian Government websites to identify relevant policy documents. These were retrieved and assessed, and relevant sections were identified and extracted. Further policies mentioned by interviewees and survey participants were also examined.

Interviews

Ten Adelaide based academics, public health specialists, municipal and State Government administrators, wellbeing and mental health practitioners, urban planners, urban designers, developers and architects were identified using snowball sampling.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, and each subject was asked about what they considered to be urban design factors that support good mental health.

Survey

An online survey was conducted comprising thirty one (n=31) responses (presented in italics throughout the document) from academics, public health specialists, municipal and State Government administrators, wellbeing and mental health practitioners, urban planners, urban designers, developers and architects.

A search was conducted on South Australian Government websites to identify relevant policy documents. These were retrieved and assessed, and relevant sections were identified and extracted. Further policies mentioned by interviewees and survey participants were also examined.

Interviews

Ten Adelaide based academics, public health specialists, municipal and State Government administrators, wellbeing and mental health practitioners, urban planners, urban designers, developers and architects were identified using snowball sampling.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, and each subject was asked about what they considered to be urban design factors that support good mental health.

Survey

An online survey was conducted comprising thirty one (n=31) responses (presented in italics throughout the document) from academics, public health specialists, municipal and State Government administrators, wellbeing and mental health practitioners, urban planners, urban designers, developers and architects.

An overview of Greater Adelaide

Figure 3: Metropolitan Adelaide, Image by Andrew Barlett

The Greater Adelaide region is built on the traditional lands and waters of five of the world’s longest enduring cultures; Kaurna people across the Adelaide Plains, Ramindjeri, Ngadjuri and Peramangk people throughout the Adelaide Hills and Ngarrindgeri people in the south.

Figure 4: Removed 2nd July 2021 due to update. Click here to view the current Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) Map of Indigenous Australia.

Greater Adelaide is now home to almost 1.5 million people from over 200 culturally, linguistically and religiously diverse backgrounds, accounting for nearly 85% of South Australia’s population. (ABS June 2016, 2). Colonised in 1836, Adelaide (named after Queen Adelaide) was designed by Malaysian born British Surveyor General Colonel William Light. Adelaide’s signature grid layout, with alternating wide and narrow streets, interspaced with six public squares and the meandering Karrawirraparri River (River Torrens), feels like a city in a park. It is one of the few remaining garden cities in the world and recognised as a National Heritage site.

Designed for the good life, greater Adelaide in South Australia is defined by its liveability, characterised by its thriving arts and cultural scene, premium food and wine, affordable living, short commute times, stunning beaches and a unique natural environment.

Designed for the good life, greater Adelaide in South Australia is defined by its liveability, characterised by its thriving arts and cultural scene, premium food and wine, affordable living, short commute times, stunning beaches and a unique natural environment.

“Everything we do is centred around a simple yet intrinsically significant desire: to create inspiring and enriching lives and improve the wellbeing and quality of life for the people of Adelaide” The City of Adelaide - Designed for life

Adelaide’s weather is

often described as Mediterranean, experiencing cool to mild winters with

moderate rainfall and warm to hot, generally dry summers. It has an average

maximum temperature of 29°C (84.2°F) in summer and 15 - 16°C (59

- 60.8°F) in winter. In summer the average sea temperature ranges from

19.7 - 21.2°C (67.5 - 70.1°F). The annual rainfall is approximately 550mm.

There are four distinct weather periods recognised in the Kaurna seasonal cycle:

There are four distinct weather periods recognised in the Kaurna seasonal cycle:

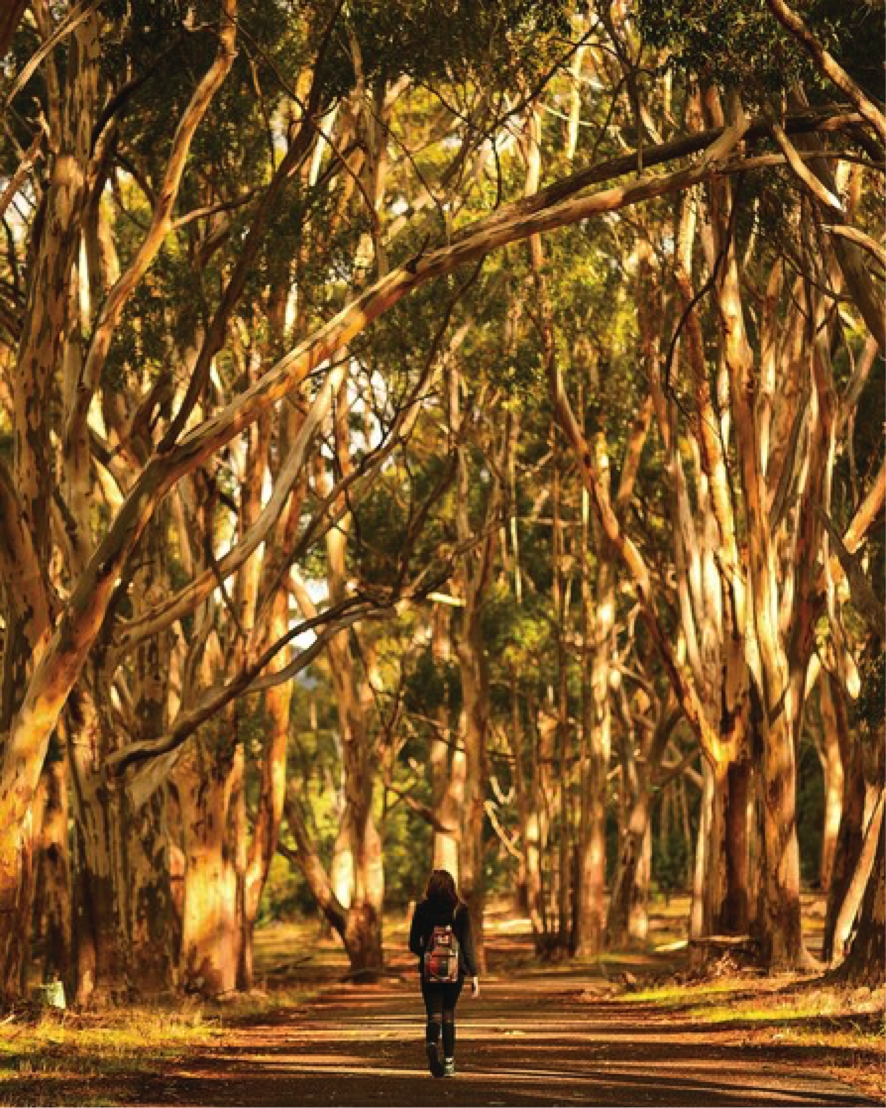

Greater

Adelaide is nestled between ‘the hills’ of the Mount Lofty Ranges to the east,

studded with small townships, nature parks, ancient Aboriginal rock art,

walking and cycling trails as well as world class food and wine producers, and

bordered to the west by expansive pristine beaches.

Figure 5: Chambers Walking Trail, Image by Jake Wundersit

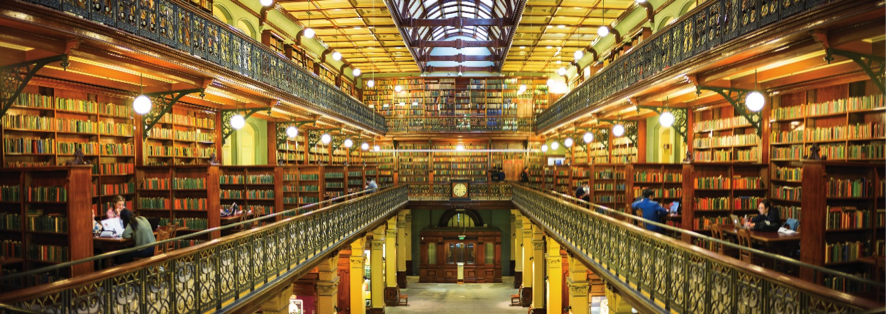

The abundance of Edwardian

and Victorian architecture constructed in locally sourced bluestone and

sandstone is most evident along the splendid boulevard of cultural

institutions, galleries and museums, including the South Australian Museum

showcasing the some of the finest and oldest known

Ediacaran fossils; the first forms of complex life, and the Botanic Garden – which hosts a State Herbarium

and a Museum of Economic Botany; the only remaining of its kind in the world.

Figure 6: State Library of South Australia, Mortlock Wing, Image by Ockert le Roux

Founded on a vision of religious tolerance, from the mid-19th century Adelaide was regarded as the "City of Churches", referring to its diversity of faiths rather than the devoutness of its citizens, and is ironically one of Australia's least religious cities

‘But South Australia deserves much, for apparently she is a hospitable home for every alien who chooses to come, and for his religion too’ - Mark Twain 1897 (3)

Yet amid the prosperity, Adelaide faces several persistent cultural, social and environmental challenges that threaten individual and collective well-being. Intractable issues that have profound human costs, hamper economic growth, create inequality and increase the need for expensive public services. This includes substance abuse, the impact of climate change, a transitioning economy, modest education outcomes and unacceptable disparity in the prosperity, health and wellbeing of first nations people.

It is anticipated that the population of Greater Adelaide is intended to grow by over half-a-million people in the next 30 years, meaning at least an additional 15,000 individuals living in the Adelaide CBD by 2036.

Recent legislation against unnecessary and unwarranted urban sprawl under the Planning, Development and Infrastructure Act 2016, intended to protect precious food production areas, meaning that the majority (85% by 2045) of all new housing in metropolitan Greater Adelaide will be infill in established urban areas. (4) This modest projected population growth and commitment to urban densification presents an outstanding and exciting opportunity for the quality design of tens of thousands of dwellings, open spaces, community amenities and transport infrastructure that is good for people and the planet.

It is anticipated that the population of Greater Adelaide is intended to grow by over half-a-million people in the next 30 years, meaning at least an additional 15,000 individuals living in the Adelaide CBD by 2036.

Recent legislation against unnecessary and unwarranted urban sprawl under the Planning, Development and Infrastructure Act 2016, intended to protect precious food production areas, meaning that the majority (85% by 2045) of all new housing in metropolitan Greater Adelaide will be infill in established urban areas. (4) This modest projected population growth and commitment to urban densification presents an outstanding and exciting opportunity for the quality design of tens of thousands of dwellings, open spaces, community amenities and transport infrastructure that is good for people and the planet.

Perceived priority of mental health in urban planning and

design in Adelaide

There is strong recognition among professional practitioners and government administrators in Adelaide of the connection between quality urban design, mental health and wellbeing.

‘Even the simplest of things [matter] like how places feel and smell. Without even realising it, our senses are deciding how we perceive places.’

‘Everything matters. Green, sustainable, comfortable, bespoke, local.’

‘Creating human scale spaces, with places for pause and contemplation, as well as inclusion, activity, recreation and inspiration. Above all, the greatest connection to nature, living elements including trees, plants, water, fauna and flora.’

‘Design needs to include spaces for active and passive activities and to connect people with nature.’

However, there was consensus that wellbeing and mental health are not currently prioritised enough, taught or measured holistically in residential, private or public development.

‘They [Project Commissioners] often think of the cost, feasibility, interest models, return income. Unfortunately, these financial interests may not coincide with prioritising health related outcomes.’

‘Need to counterbalance the negativity around how our built environment contributes to our well-being and mental health with stronger evidence and make that known by planners etc.’

‘The benefits of the principles of design and how our built environments contribute to our mental health needs to be embedded in education - in the degrees where ideals and values are ingrained.’

While the consideration of wellbeing and mental health is intrinsic for many design practitioners, barriers such as the limited scope of functional briefs and financial constraints were cited as obstructive in achieving optimal outcomes.

‘Making people and communities central to the discussions and decisions.’

‘Ensuring governments really get how important these issues are to our cities and embedding these elements in policy through Health.’

‘I think interpretive elements are a great way to provide connection to place.’

‘Free spaces. Activation for families. Adelaide CBD is now very young adult-focused, only some of the edges suit families. Playful art/water installations.’

While the value of placemaking and place management is beginning to be preemptively considered in urban design, wellbeing and mental health are not routinely measured or reported post-occupancy.

‘It’s important how a space / place is programmed after the design process.’

Quality urban design process, including the strategic development of the brief and genuine engagement with end users, was recognised as important for the ownership of outcomes and attachment to place.

‘Consultation with community, to understand end user requirements, it’s about facilitation not design.’

‘Opportunities for social interaction and inclusion. Human scale design. Connection to nature. Inclusive processes and a sense of ownership of final outcomes.’

‘Curiosity and divergent thinking at the beginning of the process – ideally prior to drafting the brief.’

‘Architects, designers and so forth would feel more appreciated if they were considered as relevant contributors to a problem solution from the beginning of a project.’

‘Bringing designers to the table to work with other professionals is in general very productive. And designers should support other professionals creative thinking too.’

GAPS and Adelaide

This section considers Greater Adelaide in the context of the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health’s GAPS framework; Green places, Active places, Pro-social places, Safe places.

GREEN PLACES

Almost all (94%) South Australian’s value interacting with nature and strongly believe in the importance of conserving and protecting the natural environment (5). While there is a public perception that Adelaide’s green spaces are being protected, recent evidence indicates it is declining; from 2013 – 2017 there was a loss of tree and shrub canopy and an increase in hard surfaces (such as paved driveways) in 17 councils in Greater Adelaide.

GREEN PLACES

Almost all (94%) South Australian’s value interacting with nature and strongly believe in the importance of conserving and protecting the natural environment (5). While there is a public perception that Adelaide’s green spaces are being protected, recent evidence indicates it is declining; from 2013 – 2017 there was a loss of tree and shrub canopy and an increase in hard surfaces (such as paved driveways) in 17 councils in Greater Adelaide.

Figure 7: Mount Lofty Botanic Garden, Michael Waterhouse Photography

Healthy Parks Healthy People South Australia

In response to the abundance of evidence which demonstrates that contact with nature improves physical health, psychological health as well as social and cultural wellbeing, the South Australian Department of Environment and Water, and the Department of Health partnered to develop and implement the Healthy Parks Healthy People South Australia 2016 – 2021 (6) framework.

The framework sets out seven focus areas:

A significant amount of work and engagement has occurred since the release of the framework including:

In response to the abundance of evidence which demonstrates that contact with nature improves physical health, psychological health as well as social and cultural wellbeing, the South Australian Department of Environment and Water, and the Department of Health partnered to develop and implement the Healthy Parks Healthy People South Australia 2016 – 2021 (6) framework.

The framework sets out seven focus areas:

- promoting physical activity in nature

- mental health benefits of contact with nature

- promoting the cultural value of Country for Aboriginal health and wellbeing

- community health and wellbeing in a changing climate

- childhood development and nature

- green infrastructure and urban settings

- biodiversity, conservation and human health.

A significant amount of work and engagement has occurred since the release of the framework including:

- Release of the first Healthy Parks Healthy People SA Action Plan ‘Realising the mental health benefits of contact with nature’ and the development of a discussion paper ‘Connecting nature and parks to mental health promotion and mental illness prevention strategies in South Australia’ to embed connection to nature and parks in mental health promotion and mental illness prevention strategies through the Suicide Prevention Strategy 2017-2021 and the SA Mental Health Strategic Plan 2017 – 2022.

- Commissioning of University researchers at University of Melbourne and RMIT to complete an evidence review of how quality green space supports health, wellbeing and biodiversity.

- Release of the second Healthy Parks, People Action Plan, ‘Quality Green Public Space’ in August 2017 to promote the greening of the public realm through the South Australian Planning Reform and the implementation of the 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide.

- The development of ‘Principles for Quality Green Public Open Space’ to support a shared understanding of the value of green open space.

- A ‘Connection to Country for Aboriginal Health and Wellbeing’ workshop was convened and attended by over 80 people from diverse Aboriginal communities and organisations, to gain a deeper understanding of how Connection to Country can be better promoted and integrated into research, policy and programs across the health and wellbeing, environment and Aboriginal sectors. This information will inform a Joint Statement of Action for Connection to Country for Aboriginal Health and Wellbeing.

Figure 8: Belair National Park, Image by Ben Stevens

Healthy Parks Healthy People has adapted the ‘5 Ways to Wellbeing’ released by the New Economics Foundation in 2008 and developed a public campaign entitled ‘5 Ways to Wellbeing in Nature’ which outlines five key actions for people to incorporate nature in their daily lives and enhance their overall wellbeing.

• Connect - make time for people and enjoy the world around you

• Be active - go outside, move your body and breathe in the fresh air

• Take notice - find a moment to take in the beauty of nature

• Keep learning - be curious about nature and discover something new

• Give - do something nice for someone and the environment

Acknowledging the economic, biophysical and social benefits of urban tree cover; trees and shrubs located in street verges, parks and backyards, the 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide aims to ‘increase urban green cover by 20% by 2045’ (Target 5). (7) Focus will be placed on ensuring that urban infill areas maintain appropriate levels of urban greenery. This target will support the work being done by councils through their tree strategies which address biodiversity and quality of vegetation.

Recognised benefits of urban tree cover include:

To protect the highly productive agricultural and horticultural land surrounding Adelaide, the urban footprint is being actively contained. By 2045, 85% of all new housing will be urban infill (Target 1) (9). Other benefits of densification include reduced car dependence, associated infrastructure costs, environmental benefits and better social connection.

BLUE INFRASTRUCTURE

There is growing evidence of a positive association between greater exposure to outdoor blue spaces and benefits to mental health and well-being. (10)

The cool temperate waters of South Australia host some of the most unique marine life on the planet. These include some of Australia’s most iconic species such as the southern right whale, bottlenose dolphin, weedy sea dragon, Australian sea lions, great white shark, little penguin, and giant Australian cuttlefish. These waters contain more varieties of marine life than the Great Barrier Reef, and around 80% of them are not found anywhere else on Earth.

• Connect - make time for people and enjoy the world around you

• Be active - go outside, move your body and breathe in the fresh air

• Take notice - find a moment to take in the beauty of nature

• Keep learning - be curious about nature and discover something new

• Give - do something nice for someone and the environment

Acknowledging the economic, biophysical and social benefits of urban tree cover; trees and shrubs located in street verges, parks and backyards, the 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide aims to ‘increase urban green cover by 20% by 2045’ (Target 5). (7) Focus will be placed on ensuring that urban infill areas maintain appropriate levels of urban greenery. This target will support the work being done by councils through their tree strategies which address biodiversity and quality of vegetation.

Recognised benefits of urban tree cover include:

- maintenance of habitat for native fauna, which can include vulnerable or threatened species in fragmented urban landscapes

- reduction of the urban heat island effect

- air quality improvements

- stormwater management improvements through reductions in the extent of impervious surfaces provision of spaces

- interaction, amenity and recreation, which improve community health and social well-being

- increased level of neighbourhood safety

- positive visual amenity for urban residents

- productive trees that can contribute to local food security (8)

To protect the highly productive agricultural and horticultural land surrounding Adelaide, the urban footprint is being actively contained. By 2045, 85% of all new housing will be urban infill (Target 1) (9). Other benefits of densification include reduced car dependence, associated infrastructure costs, environmental benefits and better social connection.

BLUE INFRASTRUCTURE

There is growing evidence of a positive association between greater exposure to outdoor blue spaces and benefits to mental health and well-being. (10)

The cool temperate waters of South Australia host some of the most unique marine life on the planet. These include some of Australia’s most iconic species such as the southern right whale, bottlenose dolphin, weedy sea dragon, Australian sea lions, great white shark, little penguin, and giant Australian cuttlefish. These waters contain more varieties of marine life than the Great Barrier Reef, and around 80% of them are not found anywhere else on Earth.

Figure 9: Semaphore Beach, Image by Michael Waterhouse Photography

To protect our native species and the unique marine environment, South Australia has created a network of 19 marine parks, totalling 2.6 million square kilometres or 44% of the state’s waters.

The Adelaide Dolphin Sanctuary is one example in the metropolitan area, just 20 minutes from the city centre, and features a 10,000-year-old mangrove forest. A resident pod of about 30 bottlenose dolphins live in the area, while another 300 visit the area regularly.

The Adelaide Dolphin Sanctuary is one example in the metropolitan area, just 20 minutes from the city centre, and features a 10,000-year-old mangrove forest. A resident pod of about 30 bottlenose dolphins live in the area, while another 300 visit the area regularly.

Figure 10: Glenelg, Image by Bunie Carthew

ACTIVE PLACES

Greater Adelaide has well established excellent informal and formal sporting, recreational and aquatic facilities and programs. The Adelaide Park Lands, which surround the CBD, have over 207 hectares of sporting open space suitable for a range of organised sports, ages and abilities.

The Office for Recreation, Sport and Racing has a vision for South Australia to be an active state grounded in the belief that sport and active recreation develops stronger, healthier, happier and safer communities. (11) People that cycle are healthier and less of a burden on the health system (Gill, J. and Celis Morales, Carlos 2017), make cities safer, create less pollution and generate few carbon emissions. In Adelaide, 31% of carbon emissions are from transport, of which 91% are from private vehicles. (12).

The Office for Recreation, Sport and Racing has a vision for South Australia to be an active state grounded in the belief that sport and active recreation develops stronger, healthier, happier and safer communities. (11) People that cycle are healthier and less of a burden on the health system (Gill, J. and Celis Morales, Carlos 2017), make cities safer, create less pollution and generate few carbon emissions. In Adelaide, 31% of carbon emissions are from transport, of which 91% are from private vehicles. (12).

Figure 11: Ebenezer Place, Adelaide. Image by the South Australian Tourism Commission

Yet, Adelaide has the potential to be one of the world’s greatest cycling cities – it is very flat, the roads are uncongested and easy to navigate. However, commuting rates have dropped 20% over the past 6 years to 7% of the population (approximately 240,000) compared to 43% of the Dutch and 30% of Danes who cycle daily. This is despite recent legislation requiring drivers to allow a minimum of one metre when passing a cyclist (or 1.5 metres where the speed limit is over 60km/h) and is thought to be largely due to the aggression of car drivers and fear of collision.

Adelaide has long been criticised as being too car-centric, with streets prioritised for vehicles, overly generous car parking, a dysfunctional ring road, under-developed public transport system, disconnected bicycle network, as well as a weak pedestrian network with delays on walking routes and frequent footpath interruptions. (Gehl, J. 2011) (13).

The State Government has committed to increase the number of cyclists to 600,000 by 2020 and partner with the Adelaide City Council to invest in cycling infrastructure and provide protected dedicated cycling corridors east-west and north-south in the central business district as well as alongside train lines.

Adelaide hosts the annual Tour Down Under event and has numerous coastal and regional bike trails as well as mountain bike paths throughout the Adelaide Hills and beyond.

Adelaide has long been criticised as being too car-centric, with streets prioritised for vehicles, overly generous car parking, a dysfunctional ring road, under-developed public transport system, disconnected bicycle network, as well as a weak pedestrian network with delays on walking routes and frequent footpath interruptions. (Gehl, J. 2011) (13).

The State Government has committed to increase the number of cyclists to 600,000 by 2020 and partner with the Adelaide City Council to invest in cycling infrastructure and provide protected dedicated cycling corridors east-west and north-south in the central business district as well as alongside train lines.

Adelaide hosts the annual Tour Down Under event and has numerous coastal and regional bike trails as well as mountain bike paths throughout the Adelaide Hills and beyond.

‘The discouraging happens when we follow the 'way we always do things', where the vehicle is more important than the pedestrian, where the sell is more important than creating soul.'

‘Improved linking of green spaces so that vehicular traffic doesn’t need to be negotiated.’

Acknowledging active transport as an important mode of commuting and its positive impact on public health and associated reduced health care costs, lower carbon emissions and less pollution, reduced traffic congestion, and improved community wellbeing and social cohesion. The 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide aims to ‘increase the share of work trips made by active transport by 30% by 2045 (Target 3)’. (14) This will be achieved in part of Adelaide by locating housing close to centres of activity, jobs, services and public transport to provide more opportunities for active travel for short daily trips (less than two km for walking and five km for cycling).

Well-designed transport infrastructure is identified as key to encouraging increased usage as it provides an appropriate level of amenity and safety for users and a more pleasant and appealing journey.

In recognition of the significant economic, social, health and environmental benefits associated with being able to walk to important amenities and services of daily life such the 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide includes a target to ‘increase the percentage of residents living in walkable neighbourhoods by 25% by 2045’ (Target 4) based on being within 400m/5 min walk of public open space (greater than 4000m2 in size) and frequent bus services (800m/10 min walk to a train or tram/O-Bahn Busway stop), within 1km/15 mins walk of a primary school and 800m/10 mins walk to shops. (15)

A five-year trial of a driverless vehicle has commenced, transporting Flinders University students from the campus to the train station in Adelaide’s southern suburbs and travels up to 30km per hour, which is also anticipated to increase active transport at either end of the journey.

By 2045, 60% of new housing will be built within a walkable distance to current and proposed transport infrastructure (Target 2). (16)

Well-designed transport infrastructure is identified as key to encouraging increased usage as it provides an appropriate level of amenity and safety for users and a more pleasant and appealing journey.

In recognition of the significant economic, social, health and environmental benefits associated with being able to walk to important amenities and services of daily life such the 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide includes a target to ‘increase the percentage of residents living in walkable neighbourhoods by 25% by 2045’ (Target 4) based on being within 400m/5 min walk of public open space (greater than 4000m2 in size) and frequent bus services (800m/10 min walk to a train or tram/O-Bahn Busway stop), within 1km/15 mins walk of a primary school and 800m/10 mins walk to shops. (15)

A five-year trial of a driverless vehicle has commenced, transporting Flinders University students from the campus to the train station in Adelaide’s southern suburbs and travels up to 30km per hour, which is also anticipated to increase active transport at either end of the journey.

By 2045, 60% of new housing will be built within a walkable distance to current and proposed transport infrastructure (Target 2). (16)

Figure 12: EcoCaddy, Image courtesy of the South Australian Tourism Commission

PRO-SOCIAL PLACES

Accessibility

Adelaide values people with disability being able to participate fully in urban life with as few barriers as possible.

Blessed with a flat terrain and community conscience, Adelaide pioneered ‘pram ramps’ throughout the city and suburbs in the 1950s.

From the late 1970s, Adelaide had a strong government commitment to disability leadership, including people with disability holding senior roles in the State Government, which brought a lived experience perspective to education, transport, health and general access improvements.

A thirty-year plan (from 1998) to create an accessible bus fleet is nearing completion with all of Adelaide’s trams and trains and train stations now accessible and almost 1,000 easy access buses retrofitted to include features such as seating for two mobility aid users and people with low vision contributing to Adelaide’s reputation as Australia’s most accessible capital city for public transport.

The public domain in Adelaide’s CBD is largely accessible and signed, including raised tactile Braille street names at major intersections.

Housing diversity

Single person households are the fastest growing household type in the state and predicted to grow by 44% to 188,000 by 2013 (up from 131,000 in 2011) in a place where the predominant form of housing has historically been detached dwellings on large allotments. (17)

The 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide seeks to increase housing diversity by 25% by 2045 (Target 6) to facilitate the supply of a diverse and well-designed range of housing types to cater for all ages and lifestyles, making the best use of land and infrastructure.

Engagement in Adelaide and South Australia

Municipalities and the South Australian Government engage communities in a variety of ways on a diverse range of issues that impact urban life. Trust, accountability and transparency of government are recurring topics of discussion across many sectors including urban life. The State Planning Reform process, currently underway, includes a stronger emphasis on quality design as well as community engagement. A Community Engagement Charter has been established placing consultation and participation at the forefront of the planning process. The Charter establishes an outcome-based, measurable approach for engaging communities on planning policy, strategies and schemes.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet has a ‘Better Together’ unit that exists to enable Government to make better decisions by bringing the voices of citizens and stakeholders into the issues that are relevant to them. ‘YourSAy’ is an online consultation hub where citizens can find and provide feedback on consultations open across the South Australian Government. Municipalities across the state also use the ‘YourSAy’ platform to engage residents.

Located in the heart of the cultural precinct, the Centre of Democracy showcases the people and ideas that have shaped democracy in South Australia and features programs and activities that challenge visitors to think again about people and power.

Accessibility

Adelaide values people with disability being able to participate fully in urban life with as few barriers as possible.

Blessed with a flat terrain and community conscience, Adelaide pioneered ‘pram ramps’ throughout the city and suburbs in the 1950s.

From the late 1970s, Adelaide had a strong government commitment to disability leadership, including people with disability holding senior roles in the State Government, which brought a lived experience perspective to education, transport, health and general access improvements.

A thirty-year plan (from 1998) to create an accessible bus fleet is nearing completion with all of Adelaide’s trams and trains and train stations now accessible and almost 1,000 easy access buses retrofitted to include features such as seating for two mobility aid users and people with low vision contributing to Adelaide’s reputation as Australia’s most accessible capital city for public transport.

The public domain in Adelaide’s CBD is largely accessible and signed, including raised tactile Braille street names at major intersections.

Housing diversity

Single person households are the fastest growing household type in the state and predicted to grow by 44% to 188,000 by 2013 (up from 131,000 in 2011) in a place where the predominant form of housing has historically been detached dwellings on large allotments. (17)

The 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide seeks to increase housing diversity by 25% by 2045 (Target 6) to facilitate the supply of a diverse and well-designed range of housing types to cater for all ages and lifestyles, making the best use of land and infrastructure.

Engagement in Adelaide and South Australia

Municipalities and the South Australian Government engage communities in a variety of ways on a diverse range of issues that impact urban life. Trust, accountability and transparency of government are recurring topics of discussion across many sectors including urban life. The State Planning Reform process, currently underway, includes a stronger emphasis on quality design as well as community engagement. A Community Engagement Charter has been established placing consultation and participation at the forefront of the planning process. The Charter establishes an outcome-based, measurable approach for engaging communities on planning policy, strategies and schemes.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet has a ‘Better Together’ unit that exists to enable Government to make better decisions by bringing the voices of citizens and stakeholders into the issues that are relevant to them. ‘YourSAy’ is an online consultation hub where citizens can find and provide feedback on consultations open across the South Australian Government. Municipalities across the state also use the ‘YourSAy’ platform to engage residents.

Located in the heart of the cultural precinct, the Centre of Democracy showcases the people and ideas that have shaped democracy in South Australia and features programs and activities that challenge visitors to think again about people and power.

Figure 13: Word on the Street. Community Arts Network

Place Attachment

There is growing recognition of the important correlation between how attached people feel to where they live and local gross domestic product (GDP) growth - the more people love their place, neighbourhood or city, the more economically vital that place will be. Beyond the function of experience with nature or social interaction is the construction of identity (18) through the reflection of one’s personal values as well as the meaning of experiences and histories of a place.

There is growing recognition of the important correlation between how attached people feel to where they live and local gross domestic product (GDP) growth - the more people love their place, neighbourhood or city, the more economically vital that place will be. Beyond the function of experience with nature or social interaction is the construction of identity (18) through the reflection of one’s personal values as well as the meaning of experiences and histories of a place.

‘Places need to reflect our values and have meaning.’

People’s perception of aesthetics; the physical beauty of the community, including the parks and green spaces, the quality of the social and cultural offerings as well as how welcoming the place is all impact of place attachment. (19)

Welcoming City

In 2018, Adelaide became Australia’s first capital Welcoming City, joining a national network of inclusive, vibrant communities internationally recognised for their ability to foster a sense of belonging and participation.

In August 2014 the City of Adelaide was declared a Refugee Welcome Zone, welcoming refugees and asylum seekers and acknowledging the difficult journey men, women and children make to Australia to seek our protection. The Welcome Centre is a safe drop-in centre for refugee families, people seeking asylum, and new arrivals to come together to access essential services and build genuine friendships.

The collective identity and shared values inform the meaning of a place.

Welcoming City

In 2018, Adelaide became Australia’s first capital Welcoming City, joining a national network of inclusive, vibrant communities internationally recognised for their ability to foster a sense of belonging and participation.

In August 2014 the City of Adelaide was declared a Refugee Welcome Zone, welcoming refugees and asylum seekers and acknowledging the difficult journey men, women and children make to Australia to seek our protection. The Welcome Centre is a safe drop-in centre for refugee families, people seeking asylum, and new arrivals to come together to access essential services and build genuine friendships.

The collective identity and shared values inform the meaning of a place.

‘Allow for diversity of experience and human exchange.’

Arts in Public Space

There is also growing evidence of the positive impact of art interventions in public space in relation to better wellbeing and mental health including improved social relations, community cohesion, building civic pride, connection to place-based culture, stronger civic participation and greater use of public space. (20) Branded ‘The Festival State’ the South Australian cultural calendar explodes with a cluster of major festivals in the early autumn months known locally as ‘Mad March’ which comprises the Adelaide Festival of Arts, the Adelaide Fringe Festival, Adelaide Writers Week and WOMADelaide.

Figure 14: WOMADelaide 2018, Image courtesy of WOMADelaide

Held in the winter month of August, the South Australian Living Artists (SALA) Festival is the biggest visual arts festival in the world – boasting participation by over 9,000 artists across over 700 venues across the state. Other festivals held throughout the year include Tarnathi (a festival celebrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island arts and culture), Adelaide Festival of Ideas, the Adelaide Fashion Festival, the Festival of Architecture and Design (FAD), the South Australian History Festival, Dream BIG Children’s Festival, OzAsia Festival, Adelaide Cabaret Festival, Umbrella Winter Festival, the Adelaide Guitar Festival, Adelaide Film Festival and FEAST festival (an LGBTI celebration).

Figure 15: WOMADelaide 2015, Image by Grant Hancock

As the home to people from over 200 cultures, a plethora of international cultural fairs also enrich Adelaide’s cultural calendar.

As South Australia is home to 18 wine regions and Adelaide, the wine capital of Australia - a cluster of food and wine festivals including Tasting Australia, CheeseFest + Ferment as well as vintage and gourmet festivals hosted by each of the five major wine regions fill the calendar (and stomachs) of locals and visitors from around the world.

Adelaide is also a designated "City of Music" by the UNESCO Creative Cities Network and hosts three of Australia's leading contemporary dance companies; the Australian Dance Theatre (ADT), Leigh Warren & Dancers and Restless Dance Theatre – nationally recognised for working with disabled and non-disabled dancers.

Public art is another important way that communities express collective identity, shared values and build meaning; to provoke a particular sentiment, express a certain narrative, be decorative, interpretive or commemorative.

As South Australia is home to 18 wine regions and Adelaide, the wine capital of Australia - a cluster of food and wine festivals including Tasting Australia, CheeseFest + Ferment as well as vintage and gourmet festivals hosted by each of the five major wine regions fill the calendar (and stomachs) of locals and visitors from around the world.

Adelaide is also a designated "City of Music" by the UNESCO Creative Cities Network and hosts three of Australia's leading contemporary dance companies; the Australian Dance Theatre (ADT), Leigh Warren & Dancers and Restless Dance Theatre – nationally recognised for working with disabled and non-disabled dancers.

Public art is another important way that communities express collective identity, shared values and build meaning; to provoke a particular sentiment, express a certain narrative, be decorative, interpretive or commemorative.

‘Public art matters – it makes us think and deepens our sense of meaning. It can disrupt – exposing unknowns, transforming our understanding of complex matters and provoking new ideas.’

Public art can amplify the cultural value of a site, space or building and significantly contribute to the aesthetic and sensory quality of a construction project, strengthening a site’s connection to place and identity. (21) Public art is a broad term that refers to a range of artistic works in the public realm. Works can be in the form of enduring iconic pieces or stand-alone works, temporary installations, performative works, media works or integrated artistic elements. Works might include custom designed sculptural wayfinding and building signage, special seating in public areas, land art, art designed to be portable between sites, and specially designed functional public realm items such as recycling bins, bollards, drinking fountains, seating, retaining walls, lighting and planting.

Figure 16: Michelle Nikou & Jason Milanovic, Glow (2009). Images courtesy of Arts South Australia.

Some municipalities allocate a percentage of development investment towards public art, it is the exception, rather than the rule. It is understood that the strongest public art outcomes are achieved through the commissioning of artists to develop site specific works. The response and concept of such works will consider location, scale, form, and materials. In contrast, the purchasing of works for installation is not responsive to site or context and is, therefore, less likely to make an integrated contribution to place.

In 2012, a Cultural Impact Guide was developed in South Australia by the Creative Communities Network; an informal network of Local Government arts and cultural managers, officers and other practitioners. Five municipalities, State Government (through Arts South Australia) and the Local Government Association of South Australia partnered to develop the work as part of a broader Cultural Impact Framework. (22) The Cultural Impact Guide: a guide to consider the impact of any decision on culture is intended as a set of provocations for Elected Members to consider the impact of their decisions on culture.

In 2012, a Cultural Impact Guide was developed in South Australia by the Creative Communities Network; an informal network of Local Government arts and cultural managers, officers and other practitioners. Five municipalities, State Government (through Arts South Australia) and the Local Government Association of South Australia partnered to develop the work as part of a broader Cultural Impact Framework. (22) The Cultural Impact Guide: a guide to consider the impact of any decision on culture is intended as a set of provocations for Elected Members to consider the impact of their decisions on culture.

Figure 17: WOMADelaide 2018, Image courtesy of WOMADelaide

Culture is encapsulated as five domains: creativity, connectedness, values, sustainability and engagement – each conveyed through three indicators as follows:

CREATIVITY: Imagination, Innovation, Expression

CONNECTEDNESS: Relationships, Commitment, Networking

VALUES: Belonging, Respect, Trust

SUSTAINABILITY: Tradition, Anticipation, Resilience

ENGAGEMENT: Interaction, Enrichment, Involvement

CREATIVITY: Imagination, Innovation, Expression

CONNECTEDNESS: Relationships, Commitment, Networking

VALUES: Belonging, Respect, Trust

SUSTAINABILITY: Tradition, Anticipation, Resilience

ENGAGEMENT: Interaction, Enrichment, Involvement

‘What would be the impact of people on public transport put their screens away and looked about they may appreciate and feel greater responsibility for their environment as well as meeting people who share their physical space, but with whom they share little sense of community?’

‘If we can promote and facilitate human interaction through the design of our environment this will diminish isolation that exacerbates mental health issues and will build wellbeing and happiness.’

‘People need time to be able to engage with their environment and the people around them.’

‘The pace of our life is working against many people's ability to engage with others and build community.’

‘A space that meets everyone’s basic needs and inviting for people from all walks of life, not giving off exclusive vibes e.g. just for richer people or “hipsters”.’

The Adelaide & Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board has used the Cultural Impact Framework to evaluate its urban sustainability program. The impact of art interventions in public space on wellbeing and mental health is not currently measured or routinely evaluated in Adelaide.

SAFE PLACES

In 2012 the State Government through the Integrated Design Commission hosted a ‘Design Lab’ to explore how to best address alcohol fuelled violence on Hindley Street; an Adelaide street notorious for alcohol related violence and aggression particularly in the early hours of the morning on weekends.

The primary ‘hunch’ or insight that emerged from the ‘Design Lab’ was the need to dilute the density of drunk and aggressive primarily male individuals. This contributed to the inspiration to introduce small venue legislation in 2013, which made it easier and cheaper to open a small bar.

In the last four years, 94 new venues have opened across Adelaide’s laneways stimulating over 1300 jobs and over $90 million in economic activity and radically transforming and revitalising the ambience of the city. Subsequent placemaking initiatives including the use of ambient lighting are being used to encourage patrons to linger longer, while feeling safe as they wander through the city.

Lighting is recognised as an important element of the city’s design, helping to improve safety and amenity, improving the quality of public spaces, a crucial aspect of supporting an evening economy which forms a pillar of the City of Adelaide’s Design Principles.

SAFE PLACES

In 2012 the State Government through the Integrated Design Commission hosted a ‘Design Lab’ to explore how to best address alcohol fuelled violence on Hindley Street; an Adelaide street notorious for alcohol related violence and aggression particularly in the early hours of the morning on weekends.

The primary ‘hunch’ or insight that emerged from the ‘Design Lab’ was the need to dilute the density of drunk and aggressive primarily male individuals. This contributed to the inspiration to introduce small venue legislation in 2013, which made it easier and cheaper to open a small bar.

In the last four years, 94 new venues have opened across Adelaide’s laneways stimulating over 1300 jobs and over $90 million in economic activity and radically transforming and revitalising the ambience of the city. Subsequent placemaking initiatives including the use of ambient lighting are being used to encourage patrons to linger longer, while feeling safe as they wander through the city.

Lighting is recognised as an important element of the city’s design, helping to improve safety and amenity, improving the quality of public spaces, a crucial aspect of supporting an evening economy which forms a pillar of the City of Adelaide’s Design Principles.

Figure 18: Alfred’s Bar, Peel Street. Image by Meaghan Coles

In 2013, the South Australian Government also introduced ‘lock out’ law, to curb alcohol fuelled violence in the city. The law stops people from entering venues after 3:00am, as well as a restriction on the sale of some drinks and a ban on glassware after 4:00am, which has reportedly resulted in a 25 per cent reduction in alcohol-related crime.

The City of Adelaide and the South Australian Police acknowledge that the design of an environment can influence the way a person feels and can influence their behaviour. Three Crime Preventions through Environmental Design (CPTED) strategies are employed to minimise the opportunity for criminal behaviour, including access control, surveillance and territorial reinforcement. (23)

The City of Adelaide and the South Australian Police acknowledge that the design of an environment can influence the way a person feels and can influence their behaviour. Three Crime Preventions through Environmental Design (CPTED) strategies are employed to minimise the opportunity for criminal behaviour, including access control, surveillance and territorial reinforcement. (23)

Principles for urban design to promote wellbeing and mental health in Adelaide

The value of good design is formally recognised at both the State and City of Adelaide level as fundamental to improving our quality of life and creating sustainable developments and environments that bring lasting benefits to communities. However, not all municipalities across greater Adelaide acknowledge quality design to the same extent.

The South Australia Planning System Reform

South Australia’s planning system is currently amid generational reform.

South Australia’s planning and development system involves:

In April 2016, the South Australian Parliament passed the Planning, Development and Infrastructure Act 2016 to implement a new planning system (replacing the Development Act 1993). This new legislation introduces the biggest changes to the South Australian Planning System in 25 years and will affect how development policy is formed and amended and how development applications are lodged and assessed.

The new system aims to be flexible, transparent and easier to use with faster and more consistent planning assessment processes, with greater emphasis on the importance of good design and community engagement. The state’s current planning policies are hosted in the South Australian Planning Policy Library. As part of the new system, the draft policies set out a state-wide framework for land use planning in South Australia that aims to address economic, environmental and social planning priorities, including housing supply and diversity, climate change and strategic transport infrastructure.

The Principles of Good Design (24) are embedded in the draft State Planning Policies. The Office for Design and Architecture South Australia (ODASA) have developed a practical framework for how good design practices can support better outcomes for the benefit of communities and neighbourhoods and demonstrate the government’s commitment to achieving design excellence in South Australia’s built environment.

The Good Design for Great Neighbourhoods and Places framework outlines the including:

The South Australia Planning System Reform

South Australia’s planning system is currently amid generational reform.

South Australia’s planning and development system involves:

- Strategic Planning - a long term vision for land use across South Australia influencing how we live, work and move.

- Planning Policy - rules for the kind of development that should take place locally to respond to community needs.

- Development Assessment - a process for gaining approval for how buildings are shaped and land is used.

- Building Policy- minimum standards for building and construction work.

In April 2016, the South Australian Parliament passed the Planning, Development and Infrastructure Act 2016 to implement a new planning system (replacing the Development Act 1993). This new legislation introduces the biggest changes to the South Australian Planning System in 25 years and will affect how development policy is formed and amended and how development applications are lodged and assessed.

The new system aims to be flexible, transparent and easier to use with faster and more consistent planning assessment processes, with greater emphasis on the importance of good design and community engagement. The state’s current planning policies are hosted in the South Australian Planning Policy Library. As part of the new system, the draft policies set out a state-wide framework for land use planning in South Australia that aims to address economic, environmental and social planning priorities, including housing supply and diversity, climate change and strategic transport infrastructure.

The Principles of Good Design (24) are embedded in the draft State Planning Policies. The Office for Design and Architecture South Australia (ODASA) have developed a practical framework for how good design practices can support better outcomes for the benefit of communities and neighbourhoods and demonstrate the government’s commitment to achieving design excellence in South Australia’s built environment.

The Good Design for Great Neighbourhoods and Places framework outlines the including:

- Context - Good design is contextual because it responds to the surrounding environment and contributes to the existing quality and future character of a place.

- Inclusive - Good design is inclusive and universal because it creates places for everyone to use and enjoy, by optimising social opportunity and equitable access.

- Durable - Good design is durable because it creates buildings and places that are fit for purpose, adaptable and long-lasting.

- Value - Good design adds value by creating desirable places that promote community and local investment, as well as enhancing social and cultural value.

- Performance - Good design performs well because it realises the project potential for the benefit of all users and the broader community.

- Sustainable - Good design is sustainable because it is environmentally responsible and supports long-term economic productivity, health and wellbeing.

Figure 19: Rundle Mall, Image by Adelaide City Council

Design review in Adelaide and South Australia

Design Review is an independent evaluation process in which a panel of built environment experts review the design quality of development proposals. It is a reliable method of promoting good design in South Australia and improving the quality of design outcomes in the built environment.

Design Review mechanisms are a free, confidential pre-lodgement service offered to developers by both the South Australian Government and City of Adelaide, guided by the Principles of Good Design and the Adelaide Design Manual respectively.

The Adelaide Design Manual

The Adelaide Design Manual sets the direction and standards regarding the design and management of high-quality, durable, flexible, accessible and sustainably designed public spaces in the City of Adelaide. The Manual builds on the city’s current strengths and draws from past experiences, locally, nationally and internationally, in urban design and sustainability principles providing future design direction for public spaces.

The Adelaide Design Manual is a toolkit for designing the streets, squares, laneways, Park Lands and public spaces in the city.

The Manual has been designed to be used by government staff, design professionals, members of the community and others with an interest in public life. It is divided into the following sections:

Design Review is an independent evaluation process in which a panel of built environment experts review the design quality of development proposals. It is a reliable method of promoting good design in South Australia and improving the quality of design outcomes in the built environment.

Design Review mechanisms are a free, confidential pre-lodgement service offered to developers by both the South Australian Government and City of Adelaide, guided by the Principles of Good Design and the Adelaide Design Manual respectively.

The Adelaide Design Manual

The Adelaide Design Manual sets the direction and standards regarding the design and management of high-quality, durable, flexible, accessible and sustainably designed public spaces in the City of Adelaide. The Manual builds on the city’s current strengths and draws from past experiences, locally, nationally and internationally, in urban design and sustainability principles providing future design direction for public spaces.

The Adelaide Design Manual is a toolkit for designing the streets, squares, laneways, Park Lands and public spaces in the city.

The Manual has been designed to be used by government staff, design professionals, members of the community and others with an interest in public life. It is divided into the following sections:

- Street Types, which defines the major streets by their function, use and movement, reinforcing their unique character and scale, and creating a long-term vision for the city.

- Street Design, which provides a range of technical and strategic approaches for creating integrated and sustainable streets that support and encourage city life.

- Furniture and Materials, which contains guidance on the elements used in the city’s streets for a consistent, complementary and high-quality approach to selection and placement.

- Greening, which provides the technical and strategic guidance for increasing trees and plantings in the city in a sustainable way, contributing to environmental and lifestyle benefits.

- Building Frontages, which explains how private buildings that face public spaces can contribute to a rich and diverse city experience through detailing and thoughtful design.

- Lighting, which provides approaches to lighting that complements the city environment, improves safety and amenity, promotes sustainability, and builds on the city’s lifestyle and character.

Figure 20: Adelaide Botanic Gardens, Image by the South Australian Tourism Commission

Healthy by Design SA

The Healthy by Design SA (25) website is a toolbox for creating liveable active places and spaces in South Australia. Many of the resources and information provided on this website have been developed locally for and by South Australians.

The Streets for People Compendium

Published in 2012 by the Government of South Australia in partnership with the Heart Foundation and the Planning Institute of Australia, the compendium reinforced the concept of ‘link and place’ to policy makers and designers, quantifying road width in relation to footpath and verge width and has influenced subsequent urban design and renewal.

The Healthy by Design SA (25) website is a toolbox for creating liveable active places and spaces in South Australia. Many of the resources and information provided on this website have been developed locally for and by South Australians.

The Streets for People Compendium

Published in 2012 by the Government of South Australia in partnership with the Heart Foundation and the Planning Institute of Australia, the compendium reinforced the concept of ‘link and place’ to policy makers and designers, quantifying road width in relation to footpath and verge width and has influenced subsequent urban design and renewal.

Other relevant aspects of Urban Design in relation to wellbeing and mental health in Adelaide

Climate change

All South Australians will experience the impact of climate change on their health and wellbeing. Understanding the risks, identifying and supporting vulnerable members of the community and developing appropriate urban design adaptation strategies will be critical to the success of healthy cities globally, including Adelaide.

Adelaide is getting warmer (overall 0.96°C warming between 1910 to 2005) and is projected to become drier with heatwaves more frequent and more severe. The number of days over 35°C in Adelaide projected to increase from their current average of 20 to 24-29 by 2030 and to 29-57 by 2090. The fire season is likely to start earlier with an increase in the number of fire danger days. Annual rainfall is projected to decrease, but the intensity likely to increase. Sea levels are rising 5 mm per year in the region and projected to rise a further 60cm by 2090.Gulf and ocean waters are warming and are also becoming more acidic as a result of absorbing higher amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, threatening marine biodiversity. (26) Temperature rises exacerbate the urban heat island effect caused by a density of hard surfaces, predominately with darker, heat-absorbent materials, loss of tree canopy cover and green open spaces, grassed areas and planted areas.

Australia’s first climate change legislation was enacted in South Australia. Carbon Neutral Adelaide is an ambition to make the City of Adelaide the world’s first carbon neutral city – to achieve zero emissions by 2050 (27). The Adelaide & Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board has developed Climate change Adaptation Plans with local government alliances, to build resilience against extreme weather events.

All South Australians will experience the impact of climate change on their health and wellbeing. Understanding the risks, identifying and supporting vulnerable members of the community and developing appropriate urban design adaptation strategies will be critical to the success of healthy cities globally, including Adelaide.

Adelaide is getting warmer (overall 0.96°C warming between 1910 to 2005) and is projected to become drier with heatwaves more frequent and more severe. The number of days over 35°C in Adelaide projected to increase from their current average of 20 to 24-29 by 2030 and to 29-57 by 2090. The fire season is likely to start earlier with an increase in the number of fire danger days. Annual rainfall is projected to decrease, but the intensity likely to increase. Sea levels are rising 5 mm per year in the region and projected to rise a further 60cm by 2090.Gulf and ocean waters are warming and are also becoming more acidic as a result of absorbing higher amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, threatening marine biodiversity. (26) Temperature rises exacerbate the urban heat island effect caused by a density of hard surfaces, predominately with darker, heat-absorbent materials, loss of tree canopy cover and green open spaces, grassed areas and planted areas.

Australia’s first climate change legislation was enacted in South Australia. Carbon Neutral Adelaide is an ambition to make the City of Adelaide the world’s first carbon neutral city – to achieve zero emissions by 2050 (27). The Adelaide & Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board has developed Climate change Adaptation Plans with local government alliances, to build resilience against extreme weather events.

Figure 21: Adelaide Botanic Gardens. Image courtesy of the South Australian Tourism Commission

Energy

Being the capital city of the driest state in the driest continent of the world, Adelaide’s reputation for resourcefulness, inventiveness and progressive thinking have emerged through the necessity to act more sustainably.

Adelaide derives most of its electricity from local privately operated gas-fired plants (Torrens Island Power Station and Pelican Point), observing strict controls to the ensure protection of the local marine environment, as well as from the national network. Gas is supplied from the Moomba Gas Processing Plant in the Cooper Basin via the Moomba Adelaide Pipeline System and the SEAGas pipeline from Victoria. South Australia generates 18% of its electricity from wind power, and has 51% of the installed capacity of wind generators in Australia. South Australia is the leading producer of wind power in Australia and over 50% of the state’s electricity is generated from renewable energy sources.

Reducing emissions while growing the economy

South Australia’s net greenhouse gas emissions have been reducing since 2005. The latest estimate indicates that net greenhouse emissions in 2012/13 were nine per cent below the 1990 baseline. South Australia’s Gross State Product (GSP) during this period grew more than 60 per cent from $55.2 billion in 1989/90 to $94 billion in 2012/13, demonstrating that economic growth can be decoupled from growth in greenhouse gas emissions.

Air quality

The air quality of greater Adelaide is constantly monitored by the State’s Environmental Protection Agency (28) and generally considered to be very good. In 2016 the Environment Protection (Air Quality) Policy 2016 was established to protect human health and the environment by providing a modernised and consolidated legislative framework. (29)

Food security

For many tens of thousands of years South Australia’s first nations people ingeniously survived sustainably on what the land and waters provided through sophisticated agricultural practices and skilled husbandry. (Pascoe,B. 2014) (30) Harvesting and storing cereals and grains, cultivating nuts, seeds and deep rooted vegetables, using fire to replenish food resources, and building complex aquaculture systems. Aboriginal lore prescribes the responsibility to nurture and respect the nature and the environment. Dreaming explains that everything in the environment; the underground, the land, the waters, the sky, fire, the wind and weather, plants and animals - holds the living essence of ancestors.

In contemporary Adelaide and many parts of South Australia, it’s easy to buy food and drink from the people who produced it, reflecting a growing recognition of the environmental consequences of food transport, refrigeration and processing as well as an intensifying affinity with ‘local’ and the land that feeds us, but comes at a cost. In the 200 years since colonialism, the introduction of predators, notably cats, foxes, rabbits and other rodents have caused the mass extinction of species. The European Carp has devastated fresh water fish stock and damages waterways. The introduction of sheep, cattle and other hooved animals has desecrated grasslands and hardened the soil - to the extent that precious rain is either absorbed more quickly or runs off the surface of the land, carrying with it soil and nutrients. The removal of perennial, deep-rooted vegetation for annual introduced crops causes groundwater to rise, dissolves salt crystallised in the soil, resulting in soil salinity. (30)

While it takes deep time to evolve the necessary customs, rituals, recipes, skills and ethics to live in a place that authentically and sustainably feeds its people, Adelaide and South Australia has the privilege of having deep and traditional Aboriginal knowledge and practices to inspire and guide the future of agriculture.

As the effects of drought devastate agriculture in South Australia, there is an increasing recognition of the need to transform agricultural practices.

Being the capital city of the driest state in the driest continent of the world, Adelaide’s reputation for resourcefulness, inventiveness and progressive thinking have emerged through the necessity to act more sustainably.

Adelaide derives most of its electricity from local privately operated gas-fired plants (Torrens Island Power Station and Pelican Point), observing strict controls to the ensure protection of the local marine environment, as well as from the national network. Gas is supplied from the Moomba Gas Processing Plant in the Cooper Basin via the Moomba Adelaide Pipeline System and the SEAGas pipeline from Victoria. South Australia generates 18% of its electricity from wind power, and has 51% of the installed capacity of wind generators in Australia. South Australia is the leading producer of wind power in Australia and over 50% of the state’s electricity is generated from renewable energy sources.

Reducing emissions while growing the economy

South Australia’s net greenhouse gas emissions have been reducing since 2005. The latest estimate indicates that net greenhouse emissions in 2012/13 were nine per cent below the 1990 baseline. South Australia’s Gross State Product (GSP) during this period grew more than 60 per cent from $55.2 billion in 1989/90 to $94 billion in 2012/13, demonstrating that economic growth can be decoupled from growth in greenhouse gas emissions.

Air quality

The air quality of greater Adelaide is constantly monitored by the State’s Environmental Protection Agency (28) and generally considered to be very good. In 2016 the Environment Protection (Air Quality) Policy 2016 was established to protect human health and the environment by providing a modernised and consolidated legislative framework. (29)

Food security

For many tens of thousands of years South Australia’s first nations people ingeniously survived sustainably on what the land and waters provided through sophisticated agricultural practices and skilled husbandry. (Pascoe,B. 2014) (30) Harvesting and storing cereals and grains, cultivating nuts, seeds and deep rooted vegetables, using fire to replenish food resources, and building complex aquaculture systems. Aboriginal lore prescribes the responsibility to nurture and respect the nature and the environment. Dreaming explains that everything in the environment; the underground, the land, the waters, the sky, fire, the wind and weather, plants and animals - holds the living essence of ancestors.

In contemporary Adelaide and many parts of South Australia, it’s easy to buy food and drink from the people who produced it, reflecting a growing recognition of the environmental consequences of food transport, refrigeration and processing as well as an intensifying affinity with ‘local’ and the land that feeds us, but comes at a cost. In the 200 years since colonialism, the introduction of predators, notably cats, foxes, rabbits and other rodents have caused the mass extinction of species. The European Carp has devastated fresh water fish stock and damages waterways. The introduction of sheep, cattle and other hooved animals has desecrated grasslands and hardened the soil - to the extent that precious rain is either absorbed more quickly or runs off the surface of the land, carrying with it soil and nutrients. The removal of perennial, deep-rooted vegetation for annual introduced crops causes groundwater to rise, dissolves salt crystallised in the soil, resulting in soil salinity. (30)

While it takes deep time to evolve the necessary customs, rituals, recipes, skills and ethics to live in a place that authentically and sustainably feeds its people, Adelaide and South Australia has the privilege of having deep and traditional Aboriginal knowledge and practices to inspire and guide the future of agriculture.

As the effects of drought devastate agriculture in South Australia, there is an increasing recognition of the need to transform agricultural practices.

Figure 22: Karl Telfer Paitya Dancers, Image by the South Australian Tourism Commission and Hash Adam Bruzzone

Figure 23: Adelaide Central Market, Image courtesy of Tourism Australia

Water security

Being one of the driest inhabited places on Earth with a population scattered across a large area, water security is an ongoing challenge for Adelaide and South Australia.

Adelaide’s water is sourced from a range of different places including the Murray River, desalinated sea water and local reservoirs: Mount Bold, Happy Valley, Myponga, Millbrook, Hope Valley, Little Para and South Para. The yield from these reservoir catchments can be as little as 10% of the city's requirements in drought years and about 60% in average years.

South Australia and importantly the city of Adelaide are at the end of the esteemed Murray-Darling Basin river system that produces one third of Australia's food supply and supports over a third of Australia's total gross value of agricultural production.

The majestic lifeline comprises Australia’s three longest rivers; the Darling (2740km long), the Murray (2520km long) and the Murrumbidgee (1575km long), which has existed for over 60 million years, since Australia split from the giant super continent, Gondwanaland.

According to the Ngarrindjeri, the Murray used to be just a stream. It became the mighty river we know today when local 'hero spirit’ Ngurunderi chased a giant cod (Ponde). As the fish swam ahead of Ngurunderi, it widened the river with sweeps of its tail. When Ngurunderi got to Tailem Bend (Tagalang), he threw a spear at the giant fish. The spear caused the cod to surge ahead of Ngurunderi, creating a long, straight stretch in the river.