Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2019:6;11 (Advance publication 2019)

|

CITY CASE STUDY

|

Urban Design and Mental Health Case Study in Montreal / Tiohtiá:ke, Canada

Rose-Anne St-Paul

Université de Montréal , Canada

Université de Montréal , Canada

The author of this article acknowledges that the study concerns unseeded Indigenous territory. The listed projects and respondents included in this study are on the lands and waters of The Kanien'kehá:ka nation. Tiohtiá:ke / Montreal is historically known as a gathering place for many First Nations, and today a diverse Indigenous population, as well as other peoples, reside there. The author recognizes the ongoing relationship between Indigenous Peoples and other people in the Tiohtiá:ke/Montreal region and acknowledges their connections to the past, present, and future.

Introduction

Almost twenty years ago, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that depression was forecasted to become the second leading cause of illness and disability after cardiovascular disease by 2020 (World Health Organization, 2001). As this year horizon is fast approaching, how can we respond to this issue? Are further negative consequences preventable? Historically, mental health practitioners of the Western World have inevitably linked the concept of "mental health" to that of "mental illness." Thus, most mental health programs focus on symptom management, illness treatment, or illness prevention. Many scholars, including the members of the Centre of Urban Design and Mental Health, argue that mental health is different from an absence of pathology. Indeed, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) challenges this association by adopting "positive mental health" as a concept in 2009. PHAC broadly defines positive mental health as "the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenge we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections, and personal dignity" (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009).

Identifying protective factors for positive mental health, such as access to nature or social interactions, contributes to the preventive and innovative quality of urban design. The body of existing literature has mostly focused on elements we can measure, such as the amount of green space or the presence of trees (Barton & Rogerson, 2017) (World Health Organization, 2016) or the pro-social, safe and inclusive aspects of space (Corcoran & Marshall, 2016). However this approach fails to address urban policymakers’ prioritization of mental health in their decisions; precisely the question we aim to address in our work.

For the Government of Quebec, the Island of Montreal is an administrative region, similar to Laval or Laurentides (the Laurentians). The city and Island of Montreal are at the heart of the Montreal Metropolitan Community, which includes municipalities on its north and south shores (Fougères & MacLeod, 2017). At the same time, there is more than one municipality on the Island of Montreal. For the purpose of this case study, we refer to the City of Montreal (Ville de Montréal) as a political entity, unless indicated otherwise. It includes portraits of the state of mental health and urban design in the city, local policies, and its current social and economic context. The data provided in the literature review concerns the province of Quebec, and where available, data specific to the city. The results of the interviews and observations shed light on local design principles and perceived prioritization of mental health. The underlying objective of this case study is to stimulate new discussions, collaborations, and actions around sustainable cohabitation in urban areas and dignified living conditions for all.

Identifying protective factors for positive mental health, such as access to nature or social interactions, contributes to the preventive and innovative quality of urban design. The body of existing literature has mostly focused on elements we can measure, such as the amount of green space or the presence of trees (Barton & Rogerson, 2017) (World Health Organization, 2016) or the pro-social, safe and inclusive aspects of space (Corcoran & Marshall, 2016). However this approach fails to address urban policymakers’ prioritization of mental health in their decisions; precisely the question we aim to address in our work.

For the Government of Quebec, the Island of Montreal is an administrative region, similar to Laval or Laurentides (the Laurentians). The city and Island of Montreal are at the heart of the Montreal Metropolitan Community, which includes municipalities on its north and south shores (Fougères & MacLeod, 2017). At the same time, there is more than one municipality on the Island of Montreal. For the purpose of this case study, we refer to the City of Montreal (Ville de Montréal) as a political entity, unless indicated otherwise. It includes portraits of the state of mental health and urban design in the city, local policies, and its current social and economic context. The data provided in the literature review concerns the province of Quebec, and where available, data specific to the city. The results of the interviews and observations shed light on local design principles and perceived prioritization of mental health. The underlying objective of this case study is to stimulate new discussions, collaborations, and actions around sustainable cohabitation in urban areas and dignified living conditions for all.

Brief Methodology

Literature review

The grey-literature available through the City of Montreal (Ville de Montréal) website was searched to identify relevant policy documents and examined other policies mentioned by interviewees.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twelve respondents: three (3) academics and two (2) professionals from the urban design, planning, and architecture sector; two (2) professionals and one (2) academic from each of the public health and mental health sectors; three (3) professionals from adjacent areas (social entrepreneurship, housing rights advocacy, climate justice). Interviewees were all based in Montreal, and the interviews were conducted by phone (8) or in person (4) between July 2017 and December 2018. Respondents were identified by network sampling ("snowball"), through their social networks, because each person was invited to refer other people "likely to participate in this research project." Semi-structured interviews were conducted in French (10) or English (2). French was translated verbatim for the purpose of this article. Using the research protocol of the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, each respondent was asked to identify what they considered to be the urban design factors promoting positive mental health, and about their perception of the priority given to mental health in urban design policies and plans, and the barriers to that prioritization.

The grey-literature available through the City of Montreal (Ville de Montréal) website was searched to identify relevant policy documents and examined other policies mentioned by interviewees.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twelve respondents: three (3) academics and two (2) professionals from the urban design, planning, and architecture sector; two (2) professionals and one (2) academic from each of the public health and mental health sectors; three (3) professionals from adjacent areas (social entrepreneurship, housing rights advocacy, climate justice). Interviewees were all based in Montreal, and the interviews were conducted by phone (8) or in person (4) between July 2017 and December 2018. Respondents were identified by network sampling ("snowball"), through their social networks, because each person was invited to refer other people "likely to participate in this research project." Semi-structured interviews were conducted in French (10) or English (2). French was translated verbatim for the purpose of this article. Using the research protocol of the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, each respondent was asked to identify what they considered to be the urban design factors promoting positive mental health, and about their perception of the priority given to mental health in urban design policies and plans, and the barriers to that prioritization.

Montreal / Tiohtiá:ke in context

Many indigenous peoples, communities, and nations have contributed to the founding of Tiohtiá:ke (or Montreal). The Kanien'kehá:ka Nation has a strong historical and uninterrupted presence in this territory, specifically in two neighbouring communities of Montreal: Kahnawà:ke and Kanehsatá:ke. This place "where the group split up or takes different paths" has become a stopping point for First Nations travelers. Its central position and influence attracted the first colonizers of the island. The French explorer, Jacques Cartier, named the mountain that overlooks the city ‘Mount Royal’ during his second trip to the continent in 1535, which became officially ‘Montreal’ in 1575. As Fougères and MacLeod put it "for people of European descent, this was a time of discovery, conquest, and possession of the land, starting with the shorelines of the main waterways, than reaching our progressively inland. For the First Nations, who had inhabited the Island of Montreal for generations, this was a period of gradual dispossession, and eventually retreat and near-extinction after Europeans decided to settle the land on a permanent basis" (Fougères & MacLeod, 2017).

Today, Montreal is considered to be the economic center of Quebec, as well as the second financial center of Canada. It has a highly diversified economy particularly around the fields of information technology, aerospace, tourism, cinema and video game industries. French is the city’s official language. In 2016, about 50% of Montreal's population declared French as the language spoken at home, followed by English at 22,8% and other languages at 18,3% (Statistics Canada, 2016). Montreal is home to more than 65 international governmental and non-governmental organizations, ranking third place behind New York and Washington (Montreal International, 2018). Quacquarelli Symonds Limited's class-leading report ranks Montreal as the 4th "best student city" in the world in 2018, and is home to six universities and several hundred research centers.

Today, Montreal is considered to be the economic center of Quebec, as well as the second financial center of Canada. It has a highly diversified economy particularly around the fields of information technology, aerospace, tourism, cinema and video game industries. French is the city’s official language. In 2016, about 50% of Montreal's population declared French as the language spoken at home, followed by English at 22,8% and other languages at 18,3% (Statistics Canada, 2016). Montreal is home to more than 65 international governmental and non-governmental organizations, ranking third place behind New York and Washington (Montreal International, 2018). Quacquarelli Symonds Limited's class-leading report ranks Montreal as the 4th "best student city" in the world in 2018, and is home to six universities and several hundred research centers.

Figure 1: A view from Mount Royal. Photograph by Daniel Baylis

On the other hand, the proportion of poor workers in the Montreal metropolitan area has steadily increased from 7.2% in 2001, 8.2% in 2006 to 8.4% in 2012. There are more than 125,000 people in the city who are employed yet living in poverty. Groups most exposed to this phenomenon include single parents under thirty, immigrants, visible minorities, youth, and socially isolated individuals. The rate of working poor is also higher amongst people without a high school diploma and those holding a part-time job (Fédération des travailleurs du Québec, 2016). Health disparities between people according to their social class persist, and poverty and inequalities have consequences on the health of more impoverished populations (Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal, 2011).

Portrait of the state of mental health in Montreal / Tiohtiá:ke

Mental disorders

In any given year, 1 in 5 Canadians experiences a mental illness or addiction problem (Smetanin et. al., 2011). The consensus in official documents is that in Montreal, around 2% of the adult population suffers from psychotic disorders and around 29% will experience major depression or anxiety disorders or disorders related to drug or alcohol use. The most common mental illnesses are depression (10% to 15% of people afflicted during their lifetime), anxiety disorders, and psychoses (Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal, 2019).

Suicide

Though the suicide rate has been declining for the past decades, Montreal has a higher suicide-related mortality rate than other large Canadian cities. However, the suicide-related mortality rate is lower in Montreal than in the rest of Quebec. In the 1980s and 1990s, the suicide rate among young men in Quebec was well above the Canadian average. In the mid-1990s, Quebec reached a peak of 40 suicides per 100,000 population, while the national average was about 10 suicides per 100,000 population. The suicide rate among young people aged 15 to 24 in Quebec was among the highest in the world. At the time, some researchers attributed this tendency to family breakdown, the lack of support for adolescents and their difficulties in imagining a bright future. Over the last 30 years, the Québec provincial government has multiplied investments in suicide prevention and awareness. Since 2000, the suicide rate among young Québecois has dropped significantly, and is now joining the national average. From 2010 to 2012, Montreal had an annual average of 11 suicides per 100,000 residents, which is higher than Toronto (8,4), but closer to Calgary (11) or Winnipeg (10,5) (Statistique Canada, CANSIM, 2016).

During the 2011-2015 period, the suicide mortality rate was lower in Montreal (11 suicides per 100,000) than in the rest of Quebec (14 per 100,000). However, given the size of its population, Montreal has the highest number of suicides, with an average of 204 suicides per year. In fact, nearly one in five people who commit suicide in Quebec live in Montreal. (Statistique Canada, CANSIM, 2016; in Blanchard et al. 2019).

Measuring mental health

There is currently no standardized method for measuring optimal mental health. National public health surveys use indicators such as the perception of mental health, life satisfaction, spiritual values, sense of community, and social support. In 2012, the ISQ drew a statistical portrait providing detailed information on thirty indicators related to the mental health of Quebecers aged 15 and over (French). This indiated that more than two-thirds (68%) of Quebec's population over the age of 15 described their mental health as "excellent" or "very good" (ISQ, 2012). The majority of people reported enjoying a high level of social support, and 72% of people described having the ability to cope with the daily demands of an "excellent" or "very good" life. More than half of people rated their ability to deal with unexpected and difficult problems as "excellent" or "very good" (58%) or felt a very "strong" or "somewhat strong" sense of belonging to their local community (55%) (ISQ, 2012).

Demographic differences in mental health

In 2014-2015, women were more likely than men to score at the high level of the psychological distress index (33% vs. 24%), and high levels of psychological distress was more widespread among people who were unemployed (43%) compared to those engaged in work (26%), study (36%) or were retired (22%) (Gouvernement du Québec. Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2016).

Today, the suicide death rate is about two and a half times higher for men than for women; particularly at risk are men aged 45 to 64, though women are more likely than men to have attempted suicide in their lifetime. The rate of hospitalization for attempted suicide among girls aged 12 to 17 years is higher than women of other age groups and men of all age groups (Blanchard et al., 2019). In general, young people aged 15 to 24 have a lower suicide rate than people in other age groups; for instance, three times lower than people aged 45 to 64.

A federal government report, written in the 1980s, indicated that the suicide rate was 10 times higher for Aboriginal youth than for other young Canadians. More than 30 years later, the situation has not improved much. In some Aboriginal communities, the suicide rate for boys exceeds 100 suicides per 100,000 population, a marked difference from the national average of 10 suicides per 100,000 population (Ansloos, 2018). This gap is also documented at the provincial level.

The risk of mental health problems is increased in those affected by substance addiction and homelessness. Homelessness is a visible social reality in the urban landscape, mainly in Montreal, but also in many other cities in Quebec. It can be situational (loss of housing due to a natural disaster, loss of employment, marital breakdown, etc.), cyclical (individuals living alternately in the street or housing, in prison or a psychiatric institution) or chronic (homeless over a long period). Increasing numbers of young people, women, seniors, and Indigenous people are homeless (Roy & Hurtubise, 2007). It is estimated that between 30% and 50% of homeless people have mental health problems, including 10% with severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and severe depression (Bonin, Fournier, Blais, & Perreault, 2005).

In any given year, 1 in 5 Canadians experiences a mental illness or addiction problem (Smetanin et. al., 2011). The consensus in official documents is that in Montreal, around 2% of the adult population suffers from psychotic disorders and around 29% will experience major depression or anxiety disorders or disorders related to drug or alcohol use. The most common mental illnesses are depression (10% to 15% of people afflicted during their lifetime), anxiety disorders, and psychoses (Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal, 2019).

Suicide

Though the suicide rate has been declining for the past decades, Montreal has a higher suicide-related mortality rate than other large Canadian cities. However, the suicide-related mortality rate is lower in Montreal than in the rest of Quebec. In the 1980s and 1990s, the suicide rate among young men in Quebec was well above the Canadian average. In the mid-1990s, Quebec reached a peak of 40 suicides per 100,000 population, while the national average was about 10 suicides per 100,000 population. The suicide rate among young people aged 15 to 24 in Quebec was among the highest in the world. At the time, some researchers attributed this tendency to family breakdown, the lack of support for adolescents and their difficulties in imagining a bright future. Over the last 30 years, the Québec provincial government has multiplied investments in suicide prevention and awareness. Since 2000, the suicide rate among young Québecois has dropped significantly, and is now joining the national average. From 2010 to 2012, Montreal had an annual average of 11 suicides per 100,000 residents, which is higher than Toronto (8,4), but closer to Calgary (11) or Winnipeg (10,5) (Statistique Canada, CANSIM, 2016).

During the 2011-2015 period, the suicide mortality rate was lower in Montreal (11 suicides per 100,000) than in the rest of Quebec (14 per 100,000). However, given the size of its population, Montreal has the highest number of suicides, with an average of 204 suicides per year. In fact, nearly one in five people who commit suicide in Quebec live in Montreal. (Statistique Canada, CANSIM, 2016; in Blanchard et al. 2019).

Measuring mental health

There is currently no standardized method for measuring optimal mental health. National public health surveys use indicators such as the perception of mental health, life satisfaction, spiritual values, sense of community, and social support. In 2012, the ISQ drew a statistical portrait providing detailed information on thirty indicators related to the mental health of Quebecers aged 15 and over (French). This indiated that more than two-thirds (68%) of Quebec's population over the age of 15 described their mental health as "excellent" or "very good" (ISQ, 2012). The majority of people reported enjoying a high level of social support, and 72% of people described having the ability to cope with the daily demands of an "excellent" or "very good" life. More than half of people rated their ability to deal with unexpected and difficult problems as "excellent" or "very good" (58%) or felt a very "strong" or "somewhat strong" sense of belonging to their local community (55%) (ISQ, 2012).

Demographic differences in mental health

In 2014-2015, women were more likely than men to score at the high level of the psychological distress index (33% vs. 24%), and high levels of psychological distress was more widespread among people who were unemployed (43%) compared to those engaged in work (26%), study (36%) or were retired (22%) (Gouvernement du Québec. Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2016).

Today, the suicide death rate is about two and a half times higher for men than for women; particularly at risk are men aged 45 to 64, though women are more likely than men to have attempted suicide in their lifetime. The rate of hospitalization for attempted suicide among girls aged 12 to 17 years is higher than women of other age groups and men of all age groups (Blanchard et al., 2019). In general, young people aged 15 to 24 have a lower suicide rate than people in other age groups; for instance, three times lower than people aged 45 to 64.

A federal government report, written in the 1980s, indicated that the suicide rate was 10 times higher for Aboriginal youth than for other young Canadians. More than 30 years later, the situation has not improved much. In some Aboriginal communities, the suicide rate for boys exceeds 100 suicides per 100,000 population, a marked difference from the national average of 10 suicides per 100,000 population (Ansloos, 2018). This gap is also documented at the provincial level.

The risk of mental health problems is increased in those affected by substance addiction and homelessness. Homelessness is a visible social reality in the urban landscape, mainly in Montreal, but also in many other cities in Quebec. It can be situational (loss of housing due to a natural disaster, loss of employment, marital breakdown, etc.), cyclical (individuals living alternately in the street or housing, in prison or a psychiatric institution) or chronic (homeless over a long period). Increasing numbers of young people, women, seniors, and Indigenous people are homeless (Roy & Hurtubise, 2007). It is estimated that between 30% and 50% of homeless people have mental health problems, including 10% with severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and severe depression (Bonin, Fournier, Blais, & Perreault, 2005).

Organization of mental health services in Montreal / Tiohtiá:ke

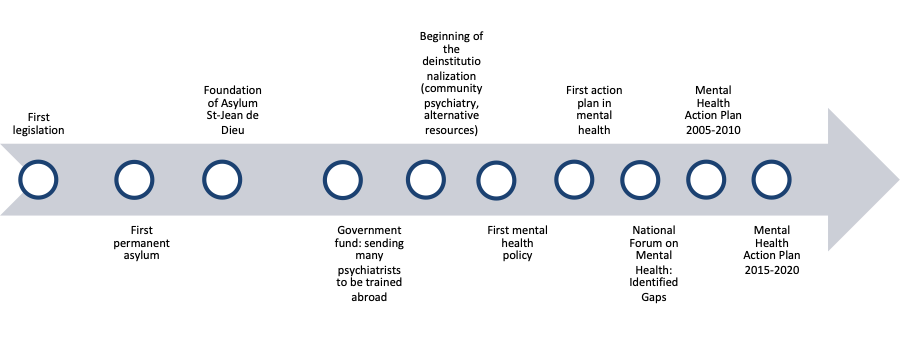

Although mental health currently falls under the health care system and is part of the provincial government concerns, it is a sector that has historically evolved in parallel, and treated separately as a "mental health system". Before the 1950s and 1960s, mental health practitioners placed sick patients in shelters that functioned as small, self-sufficient cities isolated from the rest of the community. For example, the Saint-Jean-de-Dieu Hospital (now Louis-H. Lafontaine from 1976 to 2011 and today the Institut Universitaire en santé mentale de Mont) was an independent municipality from 1897 to 1981 (Courteau, 1989).

Figure 2. Brief Mental Health Field History in Quebec (1800 - 2020)

The first deinstitutionalization movements, or the integration of psychiatric departments in general hospitals, took place after the Second World War. It led to the transfer of most autonomous patients back in the communities (Fleury, 2012). Psychiatric hospitals, as well as general hospitals, have gradually been transformed with the addition of rehabilitation activities (such as day hospitals and day centers) and outpatient services to the scope of their service offering. In general, these changes have reduced the number of beds and hospitalization time in favor of alternatives to hospitalization, achieving what mental health practitioners refer to as a progressive outpatient shift (Bachrach, 1996 in CSB, 2012).

These changes also included the development of an extensive user accommodation infrastructure, with modalities allowing for a progressive continuum of supervision and integration into the community (such as autonomous housing or autonomous housing with psychosocial support) (Piat et al., 2008 in CSB, 2012). In recent years, psychiatric services have increasingly focused on advanced treatments (including emergency and hospitalization services). As the 2005-2010 and 2015-2020 mental health action plans show, the parallel consolidation of primary care reinforced this trend and is associated with an improvement in the overall health of the population in the province (Starfield, Shi and Macinko, 2005 in CSB, 2012). Because people living with severe mental disorders were not adequately supported by front-line services, especially by general practitioners, the reforms sought to address these gaps (Fleury, Bamvita and Tremblay, 2009; Walters, Tylee in CSB 2012). Various initiatives have been introduced to improve detection and care for people with mental disorders. These include the creation of access points for vulnerable clientele (not exclusively those with mental health problems) (Fleury, 2012), sensitization campaigns, and community projects.

For a complete history of reforms, the Quebec Health and Wellness Commissioner published a report in 2012 (in French).

These changes also included the development of an extensive user accommodation infrastructure, with modalities allowing for a progressive continuum of supervision and integration into the community (such as autonomous housing or autonomous housing with psychosocial support) (Piat et al., 2008 in CSB, 2012). In recent years, psychiatric services have increasingly focused on advanced treatments (including emergency and hospitalization services). As the 2005-2010 and 2015-2020 mental health action plans show, the parallel consolidation of primary care reinforced this trend and is associated with an improvement in the overall health of the population in the province (Starfield, Shi and Macinko, 2005 in CSB, 2012). Because people living with severe mental disorders were not adequately supported by front-line services, especially by general practitioners, the reforms sought to address these gaps (Fleury, Bamvita and Tremblay, 2009; Walters, Tylee in CSB 2012). Various initiatives have been introduced to improve detection and care for people with mental disorders. These include the creation of access points for vulnerable clientele (not exclusively those with mental health problems) (Fleury, 2012), sensitization campaigns, and community projects.

For a complete history of reforms, the Quebec Health and Wellness Commissioner published a report in 2012 (in French).

Urban planning and design in Montreal / Tiohtiá:ke

The location of Montreal Island is considered exceptional from a geographical as well as from an economic viewpoint. It is situated about 1600 kilometres inland, at the confluence of three important waterways. The latter formed natural corridors into the land, along which roads were eventually built. The island is in the St-Lawrence River, which reaches out to the Atlantic Ocean and to the Great Lakes, Ohio, and Mississippi regions (Marsan, 1981). Not only was Montreal Island at the crossroads of navigable waterways, but the soil of Montreal Basin was undoubtedly suitable for farming and settlement.

With the colonization of the West, Montreal, located at the crossroads of continental traffic, was to grow rich as a trade, production, and distribution centre. Eventually, Montreal was to become a privileged centre of ideas and innovations. The climate in the form of periodic freezing of the waterways, constituted the only drawback until the introduction of mechanized means of land transportation (Marsan, 1981).

Both the French seigneurial regime and the British Conquest in 1760, affected Montreal’s architecture and urban planning. Montreal has an older division that correspond to the current Old Montreal / Old Port, but it also developed some of the characteristics widespread in North American cities, such as a layout of roads with a grid pattern. By the 1790s, Montreal – the walled town and surrounding faubourgs – was known for its flourishing commerce (Fougères & MacLeod, 2017).

With the colonization of the West, Montreal, located at the crossroads of continental traffic, was to grow rich as a trade, production, and distribution centre. Eventually, Montreal was to become a privileged centre of ideas and innovations. The climate in the form of periodic freezing of the waterways, constituted the only drawback until the introduction of mechanized means of land transportation (Marsan, 1981).

Both the French seigneurial regime and the British Conquest in 1760, affected Montreal’s architecture and urban planning. Montreal has an older division that correspond to the current Old Montreal / Old Port, but it also developed some of the characteristics widespread in North American cities, such as a layout of roads with a grid pattern. By the 1790s, Montreal – the walled town and surrounding faubourgs – was known for its flourishing commerce (Fougères & MacLeod, 2017).

Figure 3: Old Montreal. Photograph by Maria Elena Zuñiga

In the nineteenth century, the surrounding faubourgs experienced strong growth, beyond the escarpment of Sherbrooke Street, and along Saint-Laurent Boulevard, which crosses the island of Montreal, as the first "north-south" artery (oriented north-west / south-east) and dividing the Island in "halves" (east/west).

Today, Montreal is divided into 19 boroughs. According to the last national census of 2016, the city of Montreal had 1,704,694 inhabitants, with a population of 1,942,044 in the urban agglomeration, including all of the other municipalities on the Island of Montreal. Its urban area (Metropolitan Montreal Community) counts more than 4 million inhabitants and represents half of the population of Quebec (Statistics Canada, 2016). In 2018, Montreal was the 19th most populated city in North America (visited World Atlas website in 2018).

Today, Montreal is divided into 19 boroughs. According to the last national census of 2016, the city of Montreal had 1,704,694 inhabitants, with a population of 1,942,044 in the urban agglomeration, including all of the other municipalities on the Island of Montreal. Its urban area (Metropolitan Montreal Community) counts more than 4 million inhabitants and represents half of the population of Quebec (Statistics Canada, 2016). In 2018, Montreal was the 19th most populated city in North America (visited World Atlas website in 2018).

Figure 4: City of Montreal (Downtown area). Photograph by Eva Blue

Opinions about the environmental determinants of mental health

The elements of the built environment that respondents considered as factors influencing mental health in Montreal were: social interactions, safety and the right to the city, access to nature, climate change and pollution (atmospheric and auditory), public and active transportation, beauty and public art.

Social interactions

Participants spoke of the importance of encouraging social interactions and relations in various neighborhoods. Some have the impression that the city's layout revolved around the life of the nuclear family, and that most streets were built for cars. They noted a lack of connections between neighbours, a sense of disengagement from their community, alienation, and isolation. They mentioned the specific case of people who are already vulnerable or whose mobility is limited (mothers with children, older adults).

We live close to each other, but in large buildings, people do not really know each other. – Architect (translation)

How can we develop a city where people socialize more? There is less commitment to the community; we have lost the sense of what is collective. - Social entrepreneur (translation)

We need to promote intergenerational connectedness because there is value in having elders around us. We need to talk to our neighbors to break isolation. Places mothers cannot go to are hurtful. We need a way for people to find support, to encourage community, proximity, and to facilitate communication and contact. – Health professional

In Montreal, urban designers are committed to redeveloping the city from a perspective of accessibility and social interaction. As solutions or protective factors to promote positive mental health, participants identified the creation of "friendly" and inviting public spaces which can promote social exchanges. Some participants referred to their idea of Scandinavian urban models, in comparison.

Everything that makes a place friendlier or a design that facilitates encounters cannot be put aside. It is a big part of urban development, even if it is not only about that. – Urban planner (translation).

Revitalization of vacant spaces and installations

Some respondents identified pro-social designs around the city. They named different forms of installations that people could use without having to purchase anything. Public benches, picnic tables, placatory, and other furniture facilitate interactions between people.

These strategies have several objectives: to make people want to go to the public space by enhancing the street's attractiveness, to create an environment that makes you want to stay. Whether it is greening, connectivity of roads or sidewalks and cycling lanes... better space sharing in transit, and more safety at intersections. - Urban planner (translation).

For young people, offering places to support young people and young parents could help a lot. It also concerns immigrants who are deprived of their natural family network. - Psychologist (translation)

Groups such as Entremise and La Pépinière are transforming vacant lots, temporarily or for the long-term. These groups have benefited from municipal support and privileged access to public funds (Nichols & al., 2019). For spaces in transition, such as boulevards or streets undergoing construction or renovation, the city installs facilities to promote mobility and social interactions

A program from the city transforms the street, and during the transitional phase sets up facilities, but once people take ownership of the space, these facilities become more fixed – Urban planner (translation)

Accessibility of services

Another element contributing to the feeling of security in the city is the accessibility of services. Respondents identified the importance of their proximity to workplaces, points of service, community resources, and physical or creative activity sites.

Access to services should be increased, more community groups, more community resources. Make accessible also the practice of physical activity, sports, and hobbies. – Psychologist (translation)

We want people to come back to the health system... but locations of medical drugstores and mental health services are not equal. – Urban planner (translation)

Access to nature

Respondents also identified green spaces that allow people to share activities. Beyond greening on a large scale, many initiatives supported by the City of Montreal and recognized by respondents include the development of green alleyways, community gardens, and neighbourhood parks. Respondents stressed the importance of access to nature, the effect that its absence can have on their quality of life, and the efforts that should be made to increase it.

Meaningful access to green spaces is important – it really soothes the spirit when you are anxious or agitated. – Social Entrepreneur (translation)

We should have gardens on the roofs of our modern buildings. – Psychologist (translation).

It is all about Vitamin G (for Green). The effects of access to nature are innumerable. – Academic in Urban Planning (translation)

The city also established a system for residents to organize around a green alleyway project. – Urban planner (translation)

Respondents mentioned the importance of access to parks for young people (parks, playgrounds, etc.) and the elderly. The city division responsible for large parks and greening has several mandates. Its goals are to preserve and maintain 19 large parks (totaling 2,000 hectares), design and carry out development projects, ensure the protection of natural environments and more broadly, promote biodiversity in the city. In the past, several programs, policies, action plans, and strategies have emerged to frame, support, and guide the actions of this division, but the most current is the 2012 Canopy Action Plan. The goal set by this plan is to increase the canopy or tree cover index from 20% to 25% by 2021. According to the city, the canopy provides value to the environmental quality of the environment. It recognizes its impact, particularly in preventing urban heat islands as well as managing rainwater and biodiversity and protecting the health and quality of life of residents. The city also has partners who focus on environmental quality or quality of life, which are indirectly related to mental health.

Public transport and active transportation

Public and active transportation have recurrently been political and economical priorities in Montreal. Montreal's transit system is advantageous when compared to other cities in North America. Many network extension or optimization projects are currently being developed in partnership with the Government of Québec, the Agence métropolitaine de transport and public transit companies.

Obstacles to mobility are at the heart of urban design projects: land use plan (broader choices, prior to the aging of the population) road, highways (speed of movement decided by the provincial government because the road was conceptualized in a land use plan). - Urban planner (translation).

The city was built for cars, instead of people. It should be walkable to the essential services, and we should aim to design for people first, cars second. Public transport, even free transit, should be a part of the city and not separate from it. - Environmentalist.

A Réseau Quartiers Verts (RQV) works with communities to build living environments that promote active transportation (such as walking and cycling) and provide safe and welcoming urban development for all. This green neighbourhoods network project is the result of a pan-Canadian collaboration between the Montreal Urban Ecology Center, the Toronto Center for Active Transportation and the Sustainable Calgary Society. Partners work together to develop, lead, enhance, and share innovative approaches that collectively design active neighbourhoods.

Beauty, maintenance, public art

Respondents talked about beauty and its impact on the appeal of a place:

The program transforms the street, transitional phase, but once people appropriate the space, it will become more fixed. – Urban planner (translation).

Lack of maintenance of a building creates a sense of insecurity. It appears abandoned, and people do not feel like they own a space. It’s often related to the people who are residing in: well maintained, secure and aesthetically pleasing buildings are often affordable by people with more wealth. Beauty sometimes becomes a gentrification tool. – Architect (translation).

For 25 years, the city has a Public Art Office dedicated to the acquisition, preservation, and promotion of the municipal collection of public art. In 2019, the Bureau indicates the City of Montreal currently has a collection of more than 315 works of public art, which are integrated into both public spaces and municipal buildings.

Climate change and pollution (atmospheric and auditory)

The participants talked about the impact of climate change on the city, as a public health issue, which the City of Montreal is addressing on several levels (greening, public transport, etc.).

Our collective mental health is in the realm of public health. Pollution, whether atmospheric or sound, has a great impact on the development of an individual's mental health. – Social Entrepreneur (translation)

Climate change that will mainly affect the most vulnerable people: homeless people in the city in particular. – Academic Urban Planning (translation)

Climate change, with extreme events such as floods, can directly affect mental health by exposing people to trauma or helplessness. It can also indirectly affect mental health by affecting physical health (for example, exposure to extreme heat causes heat exhaustion in vulnerable people, such as elders or individuals dealing with a chronic illness, and the associated consequences for mental health) and the well-being of the community (Berry HL, 2010).

Security and right to the city

Neglected or unmaintained public spaces create a sense of insecurity in many areas of the city. Some mentioned that the lack of aesthetics and the accumulation of waste were contributing to the perception of neglect.

The sense of security when walking around the city or neighborhood is a component of urban design that can impact well-being. – Psychologist (translation)

Spaces that belong to nobody are not safe. – Architect (translation)

Gentrification

Some respondents mentioned the right to the city as a concept that also determines well-being. In Montreal, as in other North American cities, the gentrification of particular neighborhoods is an indirect consequence of a specific practice of urban design. Cities are constantly evolving, and urban evolution is generally synonymous with economic growth. However, gentrifying neighborhood changes are operating more and more in "extraterritorial, rapid, opportunistic and unilateral ways" (Harrison & Jacobs, 2016) Harrison and Jacobs state that "neighborhoods are valued and eliminated as commercial products in a process that violates the citizen's fundamental right to expect a stable housing situation" (Harrison & Jacobs, 2016).

In Canada, community organizations in all cities observe that in the context of gentrification, people who first suffer the effects of unreasonable rent increases, ultimately resulting in relocation are the ones already living in poverty. One respondent mentioned that those most at risk had precarious economic status and that beyond the loss of housing, they needed to rebuild social networks by moving to a new neighborhood.

The people [who come to see us] clearly perceive the effects of gentrification. Students who do not know if they will have the means or access to housing at a lower cost. Individuals who are alone and elders as well. Fathers or mothers of families are living with anxiety because it isn't just the loss of housing, but the access to school or kindergarten for their children, habits of life, and social network as well. [All this] creates intense anxiety. Part of our job is to inform, but we do not have social work training. We can offer very little moral support. People need to find a way to stay. – Community Organizer

Social interactions

Participants spoke of the importance of encouraging social interactions and relations in various neighborhoods. Some have the impression that the city's layout revolved around the life of the nuclear family, and that most streets were built for cars. They noted a lack of connections between neighbours, a sense of disengagement from their community, alienation, and isolation. They mentioned the specific case of people who are already vulnerable or whose mobility is limited (mothers with children, older adults).

We live close to each other, but in large buildings, people do not really know each other. – Architect (translation)

How can we develop a city where people socialize more? There is less commitment to the community; we have lost the sense of what is collective. - Social entrepreneur (translation)

We need to promote intergenerational connectedness because there is value in having elders around us. We need to talk to our neighbors to break isolation. Places mothers cannot go to are hurtful. We need a way for people to find support, to encourage community, proximity, and to facilitate communication and contact. – Health professional

In Montreal, urban designers are committed to redeveloping the city from a perspective of accessibility and social interaction. As solutions or protective factors to promote positive mental health, participants identified the creation of "friendly" and inviting public spaces which can promote social exchanges. Some participants referred to their idea of Scandinavian urban models, in comparison.

Everything that makes a place friendlier or a design that facilitates encounters cannot be put aside. It is a big part of urban development, even if it is not only about that. – Urban planner (translation).

Revitalization of vacant spaces and installations

Some respondents identified pro-social designs around the city. They named different forms of installations that people could use without having to purchase anything. Public benches, picnic tables, placatory, and other furniture facilitate interactions between people.

These strategies have several objectives: to make people want to go to the public space by enhancing the street's attractiveness, to create an environment that makes you want to stay. Whether it is greening, connectivity of roads or sidewalks and cycling lanes... better space sharing in transit, and more safety at intersections. - Urban planner (translation).

For young people, offering places to support young people and young parents could help a lot. It also concerns immigrants who are deprived of their natural family network. - Psychologist (translation)

Groups such as Entremise and La Pépinière are transforming vacant lots, temporarily or for the long-term. These groups have benefited from municipal support and privileged access to public funds (Nichols & al., 2019). For spaces in transition, such as boulevards or streets undergoing construction or renovation, the city installs facilities to promote mobility and social interactions

A program from the city transforms the street, and during the transitional phase sets up facilities, but once people take ownership of the space, these facilities become more fixed – Urban planner (translation)

Accessibility of services

Another element contributing to the feeling of security in the city is the accessibility of services. Respondents identified the importance of their proximity to workplaces, points of service, community resources, and physical or creative activity sites.

Access to services should be increased, more community groups, more community resources. Make accessible also the practice of physical activity, sports, and hobbies. – Psychologist (translation)

We want people to come back to the health system... but locations of medical drugstores and mental health services are not equal. – Urban planner (translation)

Access to nature

Respondents also identified green spaces that allow people to share activities. Beyond greening on a large scale, many initiatives supported by the City of Montreal and recognized by respondents include the development of green alleyways, community gardens, and neighbourhood parks. Respondents stressed the importance of access to nature, the effect that its absence can have on their quality of life, and the efforts that should be made to increase it.

Meaningful access to green spaces is important – it really soothes the spirit when you are anxious or agitated. – Social Entrepreneur (translation)

We should have gardens on the roofs of our modern buildings. – Psychologist (translation).

It is all about Vitamin G (for Green). The effects of access to nature are innumerable. – Academic in Urban Planning (translation)

The city also established a system for residents to organize around a green alleyway project. – Urban planner (translation)

Respondents mentioned the importance of access to parks for young people (parks, playgrounds, etc.) and the elderly. The city division responsible for large parks and greening has several mandates. Its goals are to preserve and maintain 19 large parks (totaling 2,000 hectares), design and carry out development projects, ensure the protection of natural environments and more broadly, promote biodiversity in the city. In the past, several programs, policies, action plans, and strategies have emerged to frame, support, and guide the actions of this division, but the most current is the 2012 Canopy Action Plan. The goal set by this plan is to increase the canopy or tree cover index from 20% to 25% by 2021. According to the city, the canopy provides value to the environmental quality of the environment. It recognizes its impact, particularly in preventing urban heat islands as well as managing rainwater and biodiversity and protecting the health and quality of life of residents. The city also has partners who focus on environmental quality or quality of life, which are indirectly related to mental health.

Public transport and active transportation

Public and active transportation have recurrently been political and economical priorities in Montreal. Montreal's transit system is advantageous when compared to other cities in North America. Many network extension or optimization projects are currently being developed in partnership with the Government of Québec, the Agence métropolitaine de transport and public transit companies.

Obstacles to mobility are at the heart of urban design projects: land use plan (broader choices, prior to the aging of the population) road, highways (speed of movement decided by the provincial government because the road was conceptualized in a land use plan). - Urban planner (translation).

The city was built for cars, instead of people. It should be walkable to the essential services, and we should aim to design for people first, cars second. Public transport, even free transit, should be a part of the city and not separate from it. - Environmentalist.

A Réseau Quartiers Verts (RQV) works with communities to build living environments that promote active transportation (such as walking and cycling) and provide safe and welcoming urban development for all. This green neighbourhoods network project is the result of a pan-Canadian collaboration between the Montreal Urban Ecology Center, the Toronto Center for Active Transportation and the Sustainable Calgary Society. Partners work together to develop, lead, enhance, and share innovative approaches that collectively design active neighbourhoods.

Beauty, maintenance, public art

Respondents talked about beauty and its impact on the appeal of a place:

The program transforms the street, transitional phase, but once people appropriate the space, it will become more fixed. – Urban planner (translation).

Lack of maintenance of a building creates a sense of insecurity. It appears abandoned, and people do not feel like they own a space. It’s often related to the people who are residing in: well maintained, secure and aesthetically pleasing buildings are often affordable by people with more wealth. Beauty sometimes becomes a gentrification tool. – Architect (translation).

For 25 years, the city has a Public Art Office dedicated to the acquisition, preservation, and promotion of the municipal collection of public art. In 2019, the Bureau indicates the City of Montreal currently has a collection of more than 315 works of public art, which are integrated into both public spaces and municipal buildings.

Climate change and pollution (atmospheric and auditory)

The participants talked about the impact of climate change on the city, as a public health issue, which the City of Montreal is addressing on several levels (greening, public transport, etc.).

Our collective mental health is in the realm of public health. Pollution, whether atmospheric or sound, has a great impact on the development of an individual's mental health. – Social Entrepreneur (translation)

Climate change that will mainly affect the most vulnerable people: homeless people in the city in particular. – Academic Urban Planning (translation)

Climate change, with extreme events such as floods, can directly affect mental health by exposing people to trauma or helplessness. It can also indirectly affect mental health by affecting physical health (for example, exposure to extreme heat causes heat exhaustion in vulnerable people, such as elders or individuals dealing with a chronic illness, and the associated consequences for mental health) and the well-being of the community (Berry HL, 2010).

Security and right to the city

Neglected or unmaintained public spaces create a sense of insecurity in many areas of the city. Some mentioned that the lack of aesthetics and the accumulation of waste were contributing to the perception of neglect.

The sense of security when walking around the city or neighborhood is a component of urban design that can impact well-being. – Psychologist (translation)

Spaces that belong to nobody are not safe. – Architect (translation)

Gentrification

Some respondents mentioned the right to the city as a concept that also determines well-being. In Montreal, as in other North American cities, the gentrification of particular neighborhoods is an indirect consequence of a specific practice of urban design. Cities are constantly evolving, and urban evolution is generally synonymous with economic growth. However, gentrifying neighborhood changes are operating more and more in "extraterritorial, rapid, opportunistic and unilateral ways" (Harrison & Jacobs, 2016) Harrison and Jacobs state that "neighborhoods are valued and eliminated as commercial products in a process that violates the citizen's fundamental right to expect a stable housing situation" (Harrison & Jacobs, 2016).

In Canada, community organizations in all cities observe that in the context of gentrification, people who first suffer the effects of unreasonable rent increases, ultimately resulting in relocation are the ones already living in poverty. One respondent mentioned that those most at risk had precarious economic status and that beyond the loss of housing, they needed to rebuild social networks by moving to a new neighborhood.

The people [who come to see us] clearly perceive the effects of gentrification. Students who do not know if they will have the means or access to housing at a lower cost. Individuals who are alone and elders as well. Fathers or mothers of families are living with anxiety because it isn't just the loss of housing, but the access to school or kindergarten for their children, habits of life, and social network as well. [All this] creates intense anxiety. Part of our job is to inform, but we do not have social work training. We can offer very little moral support. People need to find a way to stay. – Community Organizer

Perceived prioritization of mental health in urban planning and design in Montreal / Tiohtiá:ke

Respondents agreed that mental health was not currently considered, at least in a direct way, as a priority in public policymaking. However, they did believe that it was an indirect priority for urban planners and architects. Urban planners and architects were able to confirm a prioritization of physical health by city planners, as proven by the number of policies and action plans they were able to identify. Health professionals believe that access to natural environments, active transportation methods, and pro-social areas were important elements of positive mental health conservation.

Health professionals and professionals from adjacent fields believed that urban planners and architects had the intention to design with physical and mental health in mind, but that financial and political reasons could limit their actions. A majority of respondents were not aware of any incentive programs that would support urban design for mental health. Respondents also identified groups who were more likely to be impacted by this situation: indigenous communities, seniors, homeless people, people who were diagnosed with a mental health disorder, immigrants, population with low economic means, and people meeting several conditions.

Indigenous communities

Given an ongoing history of top-down relations between Indigenous people and the Canadian government (and non-Indigenous Canadians), First Nations, Inuit and Metis communities are facing social, health and education inequalities that reflect on the territorial organisation. These communities face specific challenges in obtaining equal access to the land and its governance. When talking about metropolitan contexts, homelessness for such citizens may become a condition of living. A research partnership by University of Quebec in Montreal, Health Research Laboratory “Vitality” (Community involvement and participation towards the making of the city) is addressing this specific issue.

Aging

In Quebec, among the population aged 65 and over, the study by Préville et al. (2009 and 2008) reported a 12-month prevalence of 12.7% of mental disorders (major depression, mania, anxiety disorders, and drug dependence), excluding age-related cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer's disease. Dementia affects 34,5% of seniors aged 85 and up (Fleury, 2012). Among older adults in hospitals, organic disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, account for just over half of the diagnoses of mental illness. 42.9% of seniors receiving home care assistance show signs of high psychological distress (Préville et al., 2007 in Fleur, 2012). For residents of long-term care facilities, the prevalence of a mental disorder is estimated at between 80% and 90%. Besides, 13.9% of seniors reported that their mental disorders (mood or anxiety) occurred when they were in this age group (Fleury, 2012).

Immigration

Health services are not immune to stereotypes and racism. Research shows that the perception of discrimination has doubled in Quebec in recent decades (Rousseau et al., 2011 in Fleury, 2016). Various initiatives in Montreal are already addressing immigrant care, even though they are still relatively marginal and not well known. For example, the Department of Psychiatry's Department of Psychiatry at the Jewish General Hospital offers clinical support to professionals, while the Jean-Talon Hospital Transcultural Clinic provides specific services to families. The lack of formal long-term institutional support for a structured clinical setting for mental health care for immigrants in Quebec significantly reduces progress in this area. However, Alliance des communautés culturelles pour l'égalité dans la santé et les services sociaux (ACCESSS) a network of community organizations, focuses on facilitating the accessibility of minorities to social and health services. Maison Multiethnique Myosotis is a community organization run by clinicians who offer therapy services and have training or interest in cross-cultural work.

Health professionals and professionals from adjacent fields believed that urban planners and architects had the intention to design with physical and mental health in mind, but that financial and political reasons could limit their actions. A majority of respondents were not aware of any incentive programs that would support urban design for mental health. Respondents also identified groups who were more likely to be impacted by this situation: indigenous communities, seniors, homeless people, people who were diagnosed with a mental health disorder, immigrants, population with low economic means, and people meeting several conditions.

Indigenous communities

Given an ongoing history of top-down relations between Indigenous people and the Canadian government (and non-Indigenous Canadians), First Nations, Inuit and Metis communities are facing social, health and education inequalities that reflect on the territorial organisation. These communities face specific challenges in obtaining equal access to the land and its governance. When talking about metropolitan contexts, homelessness for such citizens may become a condition of living. A research partnership by University of Quebec in Montreal, Health Research Laboratory “Vitality” (Community involvement and participation towards the making of the city) is addressing this specific issue.

Aging

In Quebec, among the population aged 65 and over, the study by Préville et al. (2009 and 2008) reported a 12-month prevalence of 12.7% of mental disorders (major depression, mania, anxiety disorders, and drug dependence), excluding age-related cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer's disease. Dementia affects 34,5% of seniors aged 85 and up (Fleury, 2012). Among older adults in hospitals, organic disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, account for just over half of the diagnoses of mental illness. 42.9% of seniors receiving home care assistance show signs of high psychological distress (Préville et al., 2007 in Fleur, 2012). For residents of long-term care facilities, the prevalence of a mental disorder is estimated at between 80% and 90%. Besides, 13.9% of seniors reported that their mental disorders (mood or anxiety) occurred when they were in this age group (Fleury, 2012).

Immigration

Health services are not immune to stereotypes and racism. Research shows that the perception of discrimination has doubled in Quebec in recent decades (Rousseau et al., 2011 in Fleury, 2016). Various initiatives in Montreal are already addressing immigrant care, even though they are still relatively marginal and not well known. For example, the Department of Psychiatry's Department of Psychiatry at the Jewish General Hospital offers clinical support to professionals, while the Jean-Talon Hospital Transcultural Clinic provides specific services to families. The lack of formal long-term institutional support for a structured clinical setting for mental health care for immigrants in Quebec significantly reduces progress in this area. However, Alliance des communautés culturelles pour l'égalité dans la santé et les services sociaux (ACCESSS) a network of community organizations, focuses on facilitating the accessibility of minorities to social and health services. Maison Multiethnique Myosotis is a community organization run by clinicians who offer therapy services and have training or interest in cross-cultural work.

Barriers to implementing better urban design for mental health

Respondents in the urban design field identified a lack of awareness among urban design professionals and city policymakers about mental health. Respondents in the field of urban design also identified their own lack of knowledge of mental health. Regarding the subject, they stood between discomfort (i.e., a lack of expertise) and curiosity (i.e., mentioning an interest in initiatives that explicitly prioritize mental health in the city).

All respondents indicated having the impression of working in silos and having little to no opportunity to talk about the intersection between mental health and urban design. For some mental health professionals, the urgent nature of their work does not allow them to reach beyond their expertise. All interviewees, except one, indicated a keen interest in seeing an exchange and learning space emerge from the publication of this study.

All respondents indicated having the impression of working in silos and having little to no opportunity to talk about the intersection between mental health and urban design. For some mental health professionals, the urgent nature of their work does not allow them to reach beyond their expertise. All interviewees, except one, indicated a keen interest in seeing an exchange and learning space emerge from the publication of this study.

Principles for urban design to promote mental health identified in Montreal / Tiohtiá:ke

Quebec's Ministry of Health and Social Services already identifies the living environments of individuals and the systems administered by the province (including land use planning) as social determinants of mental health. Similarly, the current planning and development plan of Montreal (in effect since 2015) seeks to "promote a quality living environment." According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, positive mental health is closely related to the living environment and social context (family, school, work, accommodation, neighbourhood, etc.). However, local development and urban design policies mostly focus on elements such as transport, safety, and universal accessibility.

Transport

The city adopted a transportation plan in 2008, reissued in 2019. It identifies the importance of transportation in improving living environments and aspires to be "a pleasant place to live, a prosperous economic pole which is respectful of its environment" (Ville de Montréal, 2008). This plan emphasizes modernizing the transportation network, giving priority to pedestrians with the launch of the Pedestrian Charter (Charte du piéton) and strengthening the cycling network. It also plans to create "green neighbourhoods" within which the city will apply a set of measures to ease traffic, improve safety, and restore peace and quality of life to residents.

Transport

The city adopted a transportation plan in 2008, reissued in 2019. It identifies the importance of transportation in improving living environments and aspires to be "a pleasant place to live, a prosperous economic pole which is respectful of its environment" (Ville de Montréal, 2008). This plan emphasizes modernizing the transportation network, giving priority to pedestrians with the launch of the Pedestrian Charter (Charte du piéton) and strengthening the cycling network. It also plans to create "green neighbourhoods" within which the city will apply a set of measures to ease traffic, improve safety, and restore peace and quality of life to residents.

Figure 5: Public transit during wintertime in a neighborhood of Montreal. Photograph by Joy Real

Safety

The city has adopted an action plan in an effort to prevent violence against women, and to promote the development of "reassuring and safe" public places (Ville de Montréal, 2015). This plan recognizes that the issues related to women’s safety have always been significant barriers to their access to the city. As such, the city issues a Planning Guide for a Safe Urban Environment, based on the six principles of security planning, and applied by the city’s governing body for urbanism (Direction de l'urbanisme) (Ville de Montréal, 2015). Similarly, the city has adopted a child policy that recognizes the importance of "safety and accessibility of urban environments." The objective is to "offer children an urban environment conducive to play and discovery, designed and developed in a secure, attractive, and universally accessible way " (City of Montreal, 2016).

Universal Accessibility

Since 2002, the city has adopted a universal accessibility policy based on an inclusive approach. The application of the concept "allows any person, regardless of his or her abilities, to use identical or similar, autonomous and simultaneous services offered to the general population"(Ville de Montréal, 2016). Interventions serve "on many fronts to improve the quality of life of citizens living with a functional limitation." A few respondents referred to universal accessibility as a possible point of entry for a conversation around positive mental health and urban design.

In 2008, the city declared itself to be an Age-Friendly Municipality based on the 2007 World Health Organization (WHO) guide: Age-Friendly Cities. MADA is a program within the governing body on families and seniors that encourages active aging. It seeks to adapt its policies, structures, and municipal services to seniors. It also supports their civic participation and promotes consultation and mobilization of the entire community around adapting environments to their needs (Ville d'Anjou, 2013). In particular, it resulted in the launch of a recent policy: the 2018-2020 Seniors Action Plan (Plan d’action pour les personnes aînées 2018-2020).

The city has adopted an action plan in an effort to prevent violence against women, and to promote the development of "reassuring and safe" public places (Ville de Montréal, 2015). This plan recognizes that the issues related to women’s safety have always been significant barriers to their access to the city. As such, the city issues a Planning Guide for a Safe Urban Environment, based on the six principles of security planning, and applied by the city’s governing body for urbanism (Direction de l'urbanisme) (Ville de Montréal, 2015). Similarly, the city has adopted a child policy that recognizes the importance of "safety and accessibility of urban environments." The objective is to "offer children an urban environment conducive to play and discovery, designed and developed in a secure, attractive, and universally accessible way " (City of Montreal, 2016).

Universal Accessibility

Since 2002, the city has adopted a universal accessibility policy based on an inclusive approach. The application of the concept "allows any person, regardless of his or her abilities, to use identical or similar, autonomous and simultaneous services offered to the general population"(Ville de Montréal, 2016). Interventions serve "on many fronts to improve the quality of life of citizens living with a functional limitation." A few respondents referred to universal accessibility as a possible point of entry for a conversation around positive mental health and urban design.

In 2008, the city declared itself to be an Age-Friendly Municipality based on the 2007 World Health Organization (WHO) guide: Age-Friendly Cities. MADA is a program within the governing body on families and seniors that encourages active aging. It seeks to adapt its policies, structures, and municipal services to seniors. It also supports their civic participation and promotes consultation and mobilization of the entire community around adapting environments to their needs (Ville d'Anjou, 2013). In particular, it resulted in the launch of a recent policy: the 2018-2020 Seniors Action Plan (Plan d’action pour les personnes aînées 2018-2020).

Case study 1: Action research projects

"Flash on my neighbourhood!" is a participatory research project that aims to better understand how the living environment influences well-being. It does so through the perspective of people living in public housing with a community psychology research methodology. Its collective approach allows these residents to identify the environmental characteristics they consider to be essential for their well-being.

Source: Flash sur mon quartier!

Source: Flash sur mon quartier!

Figure 6. A view of downtown of Montreal Photograph by Tobias

Case Study 2: Parc-Extension

Parc-Extension is a neighbourhood which has seen a significant increase in the price of rent and housing caused by the development of high-technology industries in the surrounding neighbourhoods and that of the new campus of the Université de Montréal (Campus MIL) which will open in 2019. This situation favors for-profit promoters whose offers are aimed at a new clientele of residents with incomes well above the average of the current population. This has the effect of limiting the supply of affordable housing and putting pressure on existing tenants by forcing them to leave the neighbourhood. This is a reality that has been observed in all major Canadian cities for almost a decade. Nearly 1,000 households are waiting for subsidized housing; two-thirds of the population lives below the poverty line, and one-third of the dwellings are unfit to live in. On the estimated 1,300 private dwellings located on the Campus MIL site, 15% must be social and community housing and 15% must be affordable housing (Nichols & al., 2019). Though promises have been made to add an additional 225 social and community housing units, the housing crisis in the neighbourhood is foreseen to grow. Estimates show that even if both strategies are applied to their stated extent, they will collectively do little to palliate the disproportionately large demand of incoming residents resulting from the project (Nichols & al., 2019). Mental health problems and high levels of stress as the effects of displacement and relocation are reported up to five years after displacement (Lim & al., 2017).

Figure 7: View of Parc-extension. Credit : Brick by brick (Jenny Cartwright)

Case Study 3: Mont Royal

From the mountain located at the center of the island, it is possible to view the river banks. It was, long ago, a key location for indigenous peoples travelling through the region. Throughout the city’s development, Mount Royal has played an important role in the cultural and sacred landscape of its people:

Source: Mont Royal Website

- Education: In 1821, McGill University was established on the mountain, becoming one of Canada’s first academic institutions. The mountain sides also saw the establishment of two nearby colleges (Collège de Montréal and Collège Notre-Dame) and Université de Montréal.

- Religion: The discovery of several burial sites at various locations on Mount Royal proves the mountain’s importance and sacred value to indigenous peoples living on the island of Montréal thousands of years ago. Today, it is the largest cemetery in Canada, and showcases a magnificent garden-inspired landscape. Decision-makers supported the instalment of large cemeteries on the mountain for reasons of hygiene and lack of space. The Mount Royal Cemetery for Anglophone Protestants was established in 1852, and the Catholic cemetery Notre-Dame-des-Neiges was established in 1854. The same year, the Shearith Israel cemetery (cemetery of the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue) was established and, in 1863, the Shaar Hashomayim cemetery. The mountain’s new vocation as a memorial site subsequently allowed large sections of it to avoid the threat of urbanization.

- Healthcare: After the Industrial Revolution, Mount Royal became a land of rest and healing.In 1861, Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal left its location in Old Montréal to become the first hospital on the mountain. Shortly after, Royal Victoria Hospital (1893) and Shriners Hospital for Children (1925) also settled on Mount Royal to take advantage of the therapeutic value of nature.

- Park and biodiversity: In 1876, the City of Montréal inaugurated a park accessible to Montrealers as a conserved place of nature, beauty and well-being. Today, the park is a very popular site for residents and tourists alike, sharing space for leisure, and its conservation and preservation are supported by the city and a non-profit group (Les amis de la montagne).

Source: Mont Royal Website

Figure 8: Lac-aux-Castors (Beaver Lake), artificial basin on a former swamp located on Mount-Royal. Photograph by MariamS

Case Study 4: La Pépinière

Village au Pied-du-Courant was identified by half of the respondents. It is a project that invites the residents of the south-east side of the city to (re)appropriate the banks to the river. This large, urban beach-like collective experimentation site is a space for cultural, social, educational, and festive events. On-site, it is possible to find elements of pro-social design and planning (large beach and hammocks, playground for families, sports field, reading area, etc.). The conceptualization of the site was monitored by La Pépinière | Espaces Collectifs, a non-profit organization dedicated to place making.

Figure 9: Village au Pied-du-Courant. Photograph by Clément Gross

SWOT Analysis: urban design to promote good mental health in Montreal / Tiohtiá:ke

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

|

Opportunities |

Threats |

|

|

Conclusion

Strategies for positive mental health create supportive living environments and target all communities (Joubert, 2009). The environmental protective factors can be beneficial on three levels: individual, community, and societal. Mental health and wellbeing are within the remit of urban planners, managers, designers, and developers. In Montreal, minding the GAPS (green, active, pro-social and safe places) would help professionals promote the sustainable improvement of population mental health. They should do so with curiosity and open-mindedness, as their decisions can have impacts that remain invisible until it is too late. This study raises a series of questions and ideas which are part of broader conversations around the intersectionality of different fields, creativity, social justice and right to the city.

Lessons from Montreal that could be applied to promote good mental health through urban planning and design in other cities

1. Encourage research: There is openness for research partnerships between different stakeholders (citizens, decision makers, professionals) and different sectors (universities, community, health). Some of the resources, financial and technical expertise, come from the city itself and participate in increasing awareness of the population on a variety of issues.

2. Foster discussions and interactions: Montreal has a relatively favorable social climate for communication between different stakeholders. Decision-makers and bureaucrats at different levels of the city are mostly accessible and responsive.

3. Support an active community and grassroots network: There exists a multiplication of community projects run by individuals and groups that have an acute knowledge of a variety of social issues related to urban design. A variety of the city’s programs contribute financially to the development of innovative and thought-provoking projects namely in the arts and community sector.

2. Foster discussions and interactions: Montreal has a relatively favorable social climate for communication between different stakeholders. Decision-makers and bureaucrats at different levels of the city are mostly accessible and responsive.