|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2018:5;10

|

Urban form and mental wellbeing: scoping a theoretical framework for action

Amir Hajrasoulih(1), Vicente del Rio(1), James Francis (1) and Jessica Edmondson(2)

(1) Department of City and Regional Planning, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, USA

(2) Kirk Consulting, USA

(1) Department of City and Regional Planning, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, USA

(2) Kirk Consulting, USA

Introduction

As the world becomes increasingly urbanized, planners and public health professionals are legitimately more concerned about the impacts of urban environments on the mental wellbeing of the residents. Although quality of life in general has improved throughout the world, mental health problems have increased, particularly in developed industrialised countries (Hidaka, 2012). Modern populations are increasingly “overfed, malnourished, sedentary, sunlight-deficient, sleep-deprived, and socially-isolated” (Hidaka, 2012). The urban lifestyle has contributed to the current mental health status in the United States. It is estimated that only about 17% of U.S. adults are considered to be in a state of optimal mental health (Reeves et al., 2011). 15% of high school students have seriously considered suicide, and 7% have attempted to take their own life (Eaton et al., 2007). An estimated 26% of Americans age 18 and older are living with a mental health disorder in any given year, and 46% will have a mental health disorder over the course of their lifetime (Reeves et al., 2011). Serious mental illnesses cost America $193.2 billion in lost earnings per year (Insel, 2008).

Although urban living has long being associated with a number of mental health problems, such as mood and anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia (Peen et al., 2010), it has also been associated with benefits, such as reducing suicide risk (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015) and decreasing dementia and cognitive impairment (Russ et al., 2012, Nunes, 2010). Empirical evidence from several disciplines has shown that environmental factors can both positively and negatively impact mental well-being, but there are few practical guidelines for planners on how to increase or avoid certain environments for the good of public mental well-being. The statistics are concerning, and city planners have to think about their role in improving mental wellbeing for all residents. Therefore, the scope of this research is beyond mental illness, and covers various aspects of mental wellbeing (which will be defined in the next section).

One of the few planning models relating urban design to mental well-being is Sustainability Through Happiness Framework (StHF) (Cloutier, & Pfeiffer, 2015). This model’s key components are happiness visioning, public participation, a happiness profit inventory, and systems planning and sustainability interventions. The first stage of the StHF, happiness visioning, involves planners identifying interventions that may improve “opportunities for happiness and sustainability within a neighborhood based on their prior experience and factors identified in the existing scholarly literature” (Pfeiffer and Cloutier, 2016, p. 274). Another model is the Healthy Community Design Toolkit (HCDT). The American Planning Association's Planning and Community Health Research Center and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Healthy Community Design Initiative developed HCDT in partnership. The focus of this toolkit is not on mental health, but it covers some aspects of mental health such social connectedness and safety. Both StHF and HCDT start with a checklist of desired environmental attributes. Therefore, both models can benefit from a comprehensive literature review that covers the relationship of urban form and different aspects of mental wellbeing, which is the main goal of this article.

1. The known knowns

As a first step in developing a foundation for a theoretical framework, we identified over a hundred scholarly articles and four literature reviews in English on the relationship between urban form and mental well-being. This selection was based on two criteria: 1) testing the relationship of at least one urban form variable and at least one mental well-being outcome, using quantitative methods; 2) the relationship between urban form and mental well-being outcomes had to be controlled by demographic and/or socio-economic variables. Review of these articles show that the known facts about the relationship between urban form and mental well-being are limited, complex and, in some cases, contradictory.

One reason behind this complexity is the very concept of mental well-being that includes, three interconnected types of well-being: a) hedonic (Deci & Ryan, 2008), b) psychological (Huppert, 2009), and c) social wellbeing (Keyes, 1998) (psychological and social are two aspects of eudemonic well-being). The hedonic well-being is the most primitive and short-term, resulting from the attainment of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. It depends on subjectively-determined positive mental states. The psychological and social well-being (eudemonic) relate to experiences that are objectively good for the person. The eudemonic well-being tend to be associated with long-term and enduring effects.

Urban form impacts all three dimensions of well-being. For example, a short walk in a local park provides an immediate pleasure (hedonic); turning this behavior into a daily routine restores the mind from mental fatigue (psychological); and it also provides a great opportunity for social interaction with the neighbors (social). The known measurable impacts in this experience can be identified as: mood enhancement for hedonic well-being (Butryn and Furst, 2003), stress reduction (Ulrich, 1991) and cognitive restoration (Kaplan, 1995) for psychological well-being, and social connectedness for social well-being (Leyden, 2003). In other words, it is possible to suggest planning and design strategies that promote hedonic, psychological, and social well-being through interventions in urban form.

With this in mind, our research assessed the selected peer-reviewed articles. The results of such assessment, organized into the three types of mental well-being discussed above—hedonic, psychological, and social well-being—are presented in the next section.

Urban form and hedonic wellbeing

“Affect” is one of the key constructs to explain the relationship between urban form and hedonic well-being. As defined by Morris and Guerra (2015), affect is a measure of an individual’s transitory, moment-to-moment emotional state while an activity is undertaken. Measures of affect are typically latent variables composed of multiple measures of emotional states; they may be aggregated into a single affect score (Morris & Guerra, 2015), separate positive and negative affect scores (Nisbet & Zelenski, 2011), or an array of affect categories, such as the Pleasure, Arousal and Dominance dimensions suggested by Mehrabian and Albert (1980).

The majority of the literature seems to have focused on the relationship of affect and the natural environment. For instance, Kaplan (2001) conducted a study to examine how the view from an apartment window impacts the affect balance of residents. Affect elements were grouped into three composite measures: “effective functioning,” (including general attitude towards life), “at peace,” and “distracted.” These were then correlated with the presence of seven natural or nature-oriented features within the apartment’s viewshed: a garden or landscaped area, trees, a park, a large mowed area, a farm or field, a stream or river, and wildlife. It was found that gardens correlated with higher levels of effective functioning, trees correlated with higher levels of peace, and trees and fields correlated with lower levels of distraction. All other correlations occurred at insignificant levels. Nisbet and Zelenski (2011) found that university students who walked along an outdoor path in an urbanized nature area showed significantly higher positive affect and lower negative affect than those walking along an indoor path.

A considerable number of publications deal with environmental variables such as lighting, noise, temperature and color, mostly for indoor spaces in hospitals, schools, and work places. Differences in mood under different kinds of lighting in relation to gender and age were studied by Kenz and Kers (2000). Preference for colors has been associated with mood differences between males and females, although the evidence is conflicting (Camgöz et al., 2003; Rosenstein, 1985; Read et al., 1999). We found only three studies dealing with the impact of environmental variables on hedonic well-being at the urban scale. Air pollution (real and perceived) was found to be related to lower levels of happiness (Levinson, 2012; Li et al., 2014), and noise annoyance was found to be related to peaks and to the type of noise (Dockrell & Sheild, 2004).

The impact of urban form qualities on affects is an understudied topic. In a study of viewsheds from apartments, Kaplan (2001) correlated eight built elements (quiet street, busy street, sidewalk, vacant lot, houses, nonresidential buildings, fence or wall, and parking/people) with three aggregate measures of affect (effective functioning, at peace, and distracted). She found a positive correlation between having a quiet street in an apartment’s viewshed and feelings of effective functioning, although all other relationships between built elements and affect measures were insignificant. A pilot study by Hollander and Foster (2016) investigated the impact of Traditional Neighborhood Design (TND) features on mental state. Five participants used portable electro-encephalography monitors as they walked through two neighborhoods. The study suggested that higher TND scores may correlate with higher levels of attentiveness and meditation.

Transportation seems to have a significant impact on hedonic well-being. For instance, Olsson et al. (2013) found that satisfaction with the commute had a substantial positive impact on affect balance, and that active transportation (walking and cycling) correlated with higher satisfaction than by car or public transit. Morris and Guerra (2015), examining the relationship between commute modes and an affect balance index, used multiple models to compare commutes by car (driver), car (passenger), bus, train, walking, and bicycle. Car drivers and passengers were found to have higher affect balance scores, while pedestrians and bus passengers had lower scores. This finding is not supporting what was found in Olsson et al. (2013), which can be due to different neighborhood and transportation conditions. However, cyclists were found to have a much higher affect balance than all other modes, but significance could not be established due to the very small number of cycling trips in the sample.

Urban form and psychological wellbeing

Among the titles included in our investigation, studies on the relationship between psychological well-being and urban form were found to concentrate on three concepts: stress reduction, cognitive enhancement, and overall life satisfaction.

Several studies —some considered classics in environmental psychology —have demonstrated the restorative potential of natural environments in reducing stress (Ulrich, 1986; Ulrich et al., 1991; Ulrich, 1993), promoting recovery from attentional fatigue (Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan, R., 2001; Kaplan, S., 2001; Staats et al, 2003), and even improving overall health (Laumann, Gärling & Stormark, 2003). Several studies indicate that certain environments help psychological restoration by reducing both attentional fatigue and stress levels (Hartig et al. 2003, Hartig, Mang & Evans 1991, Ulrich et al. 1991). The potential of natural environments has been described by two theoretical strains rooted in psychological restoration: Stress Recovery Theory (SRT; Ulrich 1986) and Attention Restoration Theory (ART; Kaplan 1995). SRT is concerned with affective recovery from stress, while ART involves four components: a) being away from everyday thoughts and concerns, b) fascination (interest that is easily and effortlessly engaged), c) extent (or connectedness), and d) compatibility between individual’s needs and the actions required by the environment.

The high restorative potential of nature is confirmed by research reporting the positive health benefits of views or access to urban parks and natural settings for city residents. Visiting nature offers relief from stress, according to 95% of respondents in a nationwide survey of urban dwellers in the Netherlands, (Frerichs, 2004), and urban dwellers prefer being in park-like settings over being at home, in the city center, or riding transit when experiencing attentional fatigue (Staats, van Gemerden & Hartig, 2010). Urban green spaces that are rich in species and can act as a refuge were found to be preferred by stressed individuals Grahn & Strgsdotter (2009). Small pocket parks seem to have a similar restorative quality as larger regional parks if they are designed with a high degree of “naturalness” as measured by the amount of grass and tree coverage within the space, as shown for the case of Norwegian cities (Nordh, Hartig, Hagerhall & Fry, 2009).

When the exposure to urban nature is limited, the perception of elements perceived as natural has a positive restorative effect. Urban residents prefer the presence of street trees (Kalmbach & Kielbaso, 1979; Sommer, Guenther & Barker, 1990; Wolf, 2009) and the presence of flowers in streetscapes has been reported as more restful by the participants of a study by Todorova et al. (2004). Green roofs also have restorative effects (White & Gatersleben 2011) and promote affective recovery (Lee, Williams, Sargent, Williams, and Johnson 2015).

Although most studies indicate that natural environments have greater restorative potential than urban environments (Hartig et al., 2003; Herzog et al., 1997; Ulrich et al. 1991), it appears that certain urban settings have a restoration potential that is equivalent to or greater than natural environments (Herzog et al., 2003; Nasar & Terzano, 2010; van den Berg, Jorgensen & Wilson, 2014). The most important factors affecting psychological well-being in urban settings negatively were found to be noise, over-crowding, and fear of crime (Guite, Clark & Ackrill, 2006).

Urban public gathering spaces, such as plazas, have also been evaluated for their restorative potential. Abdulkarim and Nasar (2014), for instance, found that Whyte’s (1980) fundamental elements for public open spaces––seating, triangulation, and food––contributed to the restorativeness of the plazas included in their study. Hidalgo et al. (2006) discovered that historic-cultural and recreational public spaces had the greatest restoration potential that other types of urban settings, besides finding a correlation between the “attractiveness” of urban environments and their restorative potential.

A strain of research has investigated the role of architectural characteristics in promoting psychological restoration. Galindo & Hidalgo (2005) found that openness in built environments can positively affect the probability of restoration, Stamps (1999; 2005) showed that physical components of a building’s form can influence preference in urban settings, and Lindal and Hartig (2013) found that architectural variation (entropy) had a positive effect on restoration potential while building heights had a negative effect.

We found numerous studies on the relationship between different built environment attributes and subjective well-being, as a proxy for psychological or overall mental well-being. Stutzer and Frey (2007) define subjective well-being as “an individual’s evaluation of his or her experienced positive and negative affect, happiness or satisfaction with life.” Subjective well-being may be treated as a manifest variable measured by a single question--such as “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life these days?” (Bertram & Rehdanz, 2015)--or as a latent variable composed of multiple related questions--such as questions about matters relating to the subject’s happiness or satisfaction with life (Fassio, Rollero, & De Piccoli, 2013).

Several studies seek to understand the impacts of urban density, presence of nature, land use, housing, urban nuisances, and transportation in subjective well-being. Overall, evidence suggests there is either no or negative relationship between density and subjective well-being. Florida, Mellander and Rentfrow (2013) and Ambrey and Fleming (2014) found no correlation between density and life satisfaction. Fassio et al. (2013) found that residents of areas with a population density over 500 people per square kilometer scored lower than other respondents on three World Health Organization Quality of Life indices: psychological, social, and environmental quality of life. McCrea, Shyy, and Stimson (2006) found that perceived overcrowding correlates negatively with quality of life, and that objective density correlates significantly with both perceived overcrowding (positive) and quality of life (negative).

Overall, there is a clear, positive relationship between green space and psychological well-being, which does not exist between water and psychological well-being. Ambrey and Fleming (2014) suggested that a parcel’s proximity to rivers, lakes, and creeks showed no correlation with life satisfaction, and that while living at the coastline or up to three kilometers from it correlated positively with life satisfaction, greater distances showed no such correlation. Although, the same study found no significant correlation between the percentage of a district covered by green space (a neighborhood-level measure) and life satisfaction. White, Alcock, Wheeler, and Depledge (2013) found that while the percentage of neighborhood open space covered by green space had a positive impact on subjective well-being, no such correlation was found for the percentage of the neighborhood covered by water. Sugiyama et al. (2009) found that a parcel’s increasing distance from the nearest neighborhood open space correlated negatively on the study’s Satisfaction with Life Scale and that pleasantness of the neighborhood open space correlated with higher scores. Bertram and Rehdanz (2015) found that subjective well-being peaked at 35 hectares of green space within a one-kilometer buffer and a distance of 600 meters to the nearest green space.

The evidence on the impact of housing on psychological well-being seems to be much more limited and, sometimes, contradictory. Ambrey and Fleming (2014) and Bertram and Rehdanz (2015) found no significant relationship between housing type and subjective well-being, while White et al. (2013) found that residents of semidetached and terraced homes reported significantly higher subjective well-being than those of detached homes. This last study also showed that residents in flats showed lower stress levels than those residing in detached homes (measured through the General Health Questionnaire), and found no relationship between the number of rooms per resident and subjective well-being.

Literature is also relatively limited in regards to land use. Bertram and Rehdanz (2015) found no correlation between the number of schools per square kilometer and subjective well-being. Leyden, Goldberg and Michelbach (2011) measured the correlation between participants’ opinions on their cities’ amenities and levels of subjective well-being, aggregated at the city level. Cities whose residents reported adequate access to libraries and to culture and leisure facilities also reported higher levels of subjective well-being, but no correlation was found with opinions on access to shopping, parks and sports facilities. Leyden et al. (2011) found a positive correlation between perception of convenient access to transit stops and subjective well-being at the city level.

McCrea et al. (2006) found that the relationship between objective access to amenities (a latent variable composed of the distance to schools, shopping centers, sports facilities, and hospitals) and quality of life was fully mediated by subjective access to amenities as measured in a survey; in other words, objective access to amenities has direct impact on quality of life, only if, the perception of access also exists. In this case, the results of the relevant studies are in agreement: while real proximity to amenities has no or weak impact on subjective well-being, the perceived accessibility does.

Overall, nuisance elements appear to have a weak but negative impact on subjective well-being. Ambrey and Fleming (2014) found that living within three kilometers of an airport related negatively to life satisfaction while living from three to ten kilometers from an airport, within ten kilometers of a railway, and within three kilometers of a major road had no relationship. While studying elderly adults, Sugiyama et al. (2009) found that the perceived safety of neighborhood open space correlated positively with the scores of a Satisfaction With Life Scale survey while nuisance such as trash in neighborhood open space and the quality of paths to get to them had no correlation with such scores.

While the evidence is mixed, longer commutes have either a neutral or negative correlation with subjective well-being. Commute time at the city level was found by Florida et al. (2013) to have no correlation with Gallup-Healthways Well-being Index scores. White et al. (2013) found that commutes of over 50 minutes had a positive correlation with General Health Questionnaire scores, indicating lower well-being. Olsson et al. (2013) found a negative correlation between commute time and the Satisfaction with Travel Scale, which itself correlated positively with both the Satisfaction with Life Scale and the Affect-Balance Index. Stutzer and Frey (2007) found a negative correlation between commute time and subjective well-being and Ambrey and Fleming (2014) found a negative correlation between commute time and life satisfaction.

Urban form and social wellbeing

Urban form plays multiple roles in the perceived and objective social environment, and the social environment has an impact on the social-well-being of individuals. Features of social environments that may operate as stressors, such as perceptions of safety and social disorder, have been linked to mental well-being, as have factors that could buffer the adverse effects of stress, such as social cohesion and social capital (Mair et al., 2008). Social participation and integration in the immediate social environment are important to both mental and physical health (De Silva et al., 2005). Other important aspects include the stability of social connections, such as the existence of stable and supportive local social environments or neighborhoods in which to live and work.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified the social elements of mental well-being as social acceptance, beliefs in the potential of people and society as a whole, personal self-worth and usefulness to society, and sense of community (CDC, 2016). There are several related terms for the various components of social well-being: social capital, social connectedness, and social cohesion. Social capital is a form of economic and cultural capital in which social networks are central, and transactions are marked by reciprocity, trust and cooperation (Hassen & Kaufman, 2016). Social connectedness is the experience of belonging and relatedness between people (Dictionary.net, n.d.). At an individual level, social connectedness involves the quality and number of connections one has with other people in a social circle of family, friends, and acquaintances (De Silva et al., 2005). Social cohesion is the degree to which those in a social system identify with it and feel bound to support it, especially its norms, beliefs, and values (Bjornstrom & Ralston, 2014). A cohesive society works toward the well-being of all its members, fights exclusion and marginalization, creates a sense of belonging, promotes trust, and offers its members the opportunity of upward mobility.

The majority of articles, looked at social connectedness variables as they relate to the mental well-being variables and other social environment variables at the neighborhood level. For example, one study found that perceptions of social cohesion and social order are associated with greater levels of neighborhood satisfaction, whereas perceptions of neighborhood social support have no effect on satisfaction (Dassopoulos & Monnat, 2011). Social cohesion was also found to increase both the perception of neighborhood safety and self-rated health (De Jesus, Puleo, Shelton & Emmons, 2010; Poortinga, 2012). On the other hand, a deprived neighborhood leads to both a decrease in social cohesion and self-rated health (Poortinga, 2012). One of the studies also found that social support had a positive impact on females’ perception of neighborhood safety, but had no effect on males’ perception (De Jesus, Puleo, Shelton & Emmons, 2010). The authors also found that social networks had the reverse impact: males’ perception of neighborhood safety increased while there was impact on females’ perception of safety (De Jesus, Puleo, Shelton & Emmons, 2010). At the individual level, Bjornstrom & Ralston (2016) demonstrate that perceived danger and concentrated disadvantage have strong negative correlations with perceived cohesion, regardless of the objective built environment characteristics. Participation in a local business or civic group was found to increase self-rated health but had no impact on neighborhood satisfaction (Poortinga, 2012; Dassopoulos, & Monnat, 2011). Volunteering, however, was found to positively impact neighborhood satisfaction (Dassopoulos, & Monnat, 2011).

Community attachment theories suggest that perceptions of cohesion within one’s neighborhood are important because solidarity becomes a resource to effect positive change through both formal and informal community organizing and problem solving (Dassopoulos & Monnat, 2011). Referring back to the U.S. Center for Disease Control’s definition, one of the aspects of an individual in a state of mental well-being includes the ability to make a contribution to his or her community. This makes the linkage between social well-being and community participation, an important facet of planning that has urban design implications. The following paragraphs discuss the role of urban form in promoting social connectedness and individuals’ social well-being.

King (2013) found that increasing proportions of large building types are associated with increasing negative social relations (social cohesion, social capital and neighborliness) compared to single-unit housing. Diversity in housing age had a positive impact on social cohesion, social capital and neighborliness (King, 2013). When examining the timing of construction, recent construction was found to negatively impact social control. A literature review of eleven urban design element found that mixed tenure of residents had no impact on sense of community; however, it facilitates desirable places to live in the longer term which can allow social capital to grow (Paranagamage, Austin, Price, & Khandokar, 2010). Another study found no relationship between length of residency and sense of community (Wilkerson, Carlson, Yen, & Michael, 2016).

Bjornstrom & Ralston (2016) examined the ways that certain urban form characteristics at the neighborhood scale are associated with experienced social cohesion and how concentrated disadvantage and perceived danger moderate the relationships. They found that a neighborhood with a high prevalence of trees in a neighborhood perceived to be dangerous led to a decrease in social cohesion, whereas a high prevalence of trees in a neighborhood perceived to be safe led to an increase in social cohesion.

A review of fifteen articles found that the availability of public space correlated with an increase in social capital (Hassen & Kaufman, 2016). The availability of public space was found to have no impact on sense of identity, however the authors found that an increase in local facilities led to an increased sense of community (English Partnerships and the Housing Corporation, 2000). Similar to the latter finding, Zhu (2015) found that the presence of communal space within a neighborhood increased community participation. Zhu and Fu (2016) looked at the use and appraisal of communal space in China across 39 urban neighborhoods. They found the appraisal of communal space had no impact on social capital or neighborhood participation, however increased neighborhood attachment. The actual use of communal space had no impact on neighborhood participation or neighborhood attachment, however increased social capital (Zhu & Fu, 2016).

In regards to land use, one study found that low mixed-use neighborhoods increased residents’ sense of community (Wood, Frank, & Giles-Corti, 2010). An increase in the “area ratio” of commercial spaces in a neighborhood had a positive impact on sense of community (Wood, Frank, & Giles-Corti, 2010). Another study demonstrated the residents' higher perceived access to key resources was associated with higher neighborhood participation (Richard et al., 2009). When looking at mixed-use in general, a literature review of eleven studies found that it increased happiness and sense of identity, which contributes to the growth of social capital (Paranagamage, Austin, Price, & Khandokar, 2010). In sum, the findings related to mixed-use facilities were contradictory. Some studies found that mixed-use has a negative impact on sense of community whereas others found that mixed-use facilitates social inclusion by attracting a wider population in age and ethnicity, offering employment opportunity, encouraging social exchange, building social capital, and contributing to reduced feelings of isolation and depression in communities.

Several studies looked at the social impacts of walkability and found mixed results. One study found no significant relationship between a walkability index and three sociability indicators: social interaction, social cohesion and social control. One study found no impact on social capital (Sander, 2002). However a positive relationship was found with sense of community for younger but not older respondents (Toit, Cerin, Leslie, & Owen, 2007). Walkability was found to have a strong positive association with community engagement and sense of community (Renalds, Smith & Hale, 2010; Paranagamage, Austin, Price, & Khandokar, 2010). Another found that sense of community was positively associated with walking, but only leisure walking, not brisk (for transport) walking (Toit, Cerin, Leslie & Owen, 2007). At the block level, streets with more than 90% sidewalk connectivity had a significant positive impact on social cohesion (Wilkerson, Carlson, Yen, & Michael, 2016). The prevalence of sidewalks in a high disadvantaged neighborhood led to an increase in social cohesion in neighborhoods perceived both dangerous and safe. Bjornstrom and Ralston (2016) also looked at the prevalence of sidewalks in a low disadvantaged neighborhood in a perceived safe neighborhood and found no impact on social cohesion, while when in a perceived dangerous neighborhood, the prevalence of sidewalks decreased social cohesion. They interpret this result as the extent to which sidewalks facilitate cohesion in high-disadvantage neighborhoods is weakened by perceived danger.

In regards to transportation, one study found that transportation options offering a sense of mobility led to an increase in social cohesion (Ottoni, Sims-Gould, Winters, Heijnen, & McKay, 2016). At the block level, traffic-calming devices had no impact on social cohesion (Wilkerson, Carlson, Yen, & Michael, 2016). Additionally, walkability had no significant impact on social interaction, which in turn had no significant impact on sense of community.

Examining a smaller scale, spaces and enclosures with moderate openness without visual and acoustic distraction are the most desirable to promote pro-social behaviors (social participation; i.e., observing, smiling, laughing, and being physically active) among older adults with dementia and young children (Cerruti & Shepley, 2016). The visibility of neighbors led to the increased sense of community (Wood, Frank, & Giles-Corti, 2010).

Hochschild (2015) examined the difference in street types and found that different types of cul-de-sacs effect neighborly interconnectedness in different ways. The study found that neighbors living on bulb cul-de-sacs experience greater social cohesion than those on dead-end cul-de-sacs and through streets. Additionally, the shared social space, lack of outsiders and sense of territoriality on bulb and dead-end cul-de-sacs promote stronger neighborly ties than through streets. One article studied New Urbanist design attributes and found that houses without gates and that are marked by clear edges showed no significant relationship to social capital (Sander, 2002). The presence of bars on some windows had no impact on social cohesion, while residences with front porches led to an increase in social cohesion (Wilkerson, Carlson, Yen, & Michael, 2016). At the neighborhood level, one study found the availability of benches along the street positively contributed to older adults’ mobility, social cohesion and social capital (Ottoni, Sims-Gould, Winters, Heijnen, & McKay, 2016).

At the parcel level, a semi-enclosed spatial configuration led to an increased social interaction between older adults and children (Cerruti & Shepley, 2016). The older children's prosocial behaviors were likely facilitated by specific design features such as adequate personal space, the perception of openness, and spaces that provide both prospect and refuge in relation to spatial enclosure (Cerruti & Shepley, 2016). At the block level, one study found that the availability of tables in parks led to an increase in social cohesion (Anderson, Ruggeri, Steemers, & Huppert, 2016).

2. A model to direct studies on urban form and mental well-being

Our review of the existing literature revealed significant gaps, illustrated in Table 1. In some cases, these gaps result from contradictory information (for instance, the relationship between transportation mode and hedonic well-being), while in others, they result from studies that failed to find significant relationships (for instance, the relationship between housing type and psychological well-being). In other cases, the publication or study is absent of any data.

Although urban living has long being associated with a number of mental health problems, such as mood and anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia (Peen et al., 2010), it has also been associated with benefits, such as reducing suicide risk (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015) and decreasing dementia and cognitive impairment (Russ et al., 2012, Nunes, 2010). Empirical evidence from several disciplines has shown that environmental factors can both positively and negatively impact mental well-being, but there are few practical guidelines for planners on how to increase or avoid certain environments for the good of public mental well-being. The statistics are concerning, and city planners have to think about their role in improving mental wellbeing for all residents. Therefore, the scope of this research is beyond mental illness, and covers various aspects of mental wellbeing (which will be defined in the next section).

One of the few planning models relating urban design to mental well-being is Sustainability Through Happiness Framework (StHF) (Cloutier, & Pfeiffer, 2015). This model’s key components are happiness visioning, public participation, a happiness profit inventory, and systems planning and sustainability interventions. The first stage of the StHF, happiness visioning, involves planners identifying interventions that may improve “opportunities for happiness and sustainability within a neighborhood based on their prior experience and factors identified in the existing scholarly literature” (Pfeiffer and Cloutier, 2016, p. 274). Another model is the Healthy Community Design Toolkit (HCDT). The American Planning Association's Planning and Community Health Research Center and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Healthy Community Design Initiative developed HCDT in partnership. The focus of this toolkit is not on mental health, but it covers some aspects of mental health such social connectedness and safety. Both StHF and HCDT start with a checklist of desired environmental attributes. Therefore, both models can benefit from a comprehensive literature review that covers the relationship of urban form and different aspects of mental wellbeing, which is the main goal of this article.

1. The known knowns

As a first step in developing a foundation for a theoretical framework, we identified over a hundred scholarly articles and four literature reviews in English on the relationship between urban form and mental well-being. This selection was based on two criteria: 1) testing the relationship of at least one urban form variable and at least one mental well-being outcome, using quantitative methods; 2) the relationship between urban form and mental well-being outcomes had to be controlled by demographic and/or socio-economic variables. Review of these articles show that the known facts about the relationship between urban form and mental well-being are limited, complex and, in some cases, contradictory.

One reason behind this complexity is the very concept of mental well-being that includes, three interconnected types of well-being: a) hedonic (Deci & Ryan, 2008), b) psychological (Huppert, 2009), and c) social wellbeing (Keyes, 1998) (psychological and social are two aspects of eudemonic well-being). The hedonic well-being is the most primitive and short-term, resulting from the attainment of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. It depends on subjectively-determined positive mental states. The psychological and social well-being (eudemonic) relate to experiences that are objectively good for the person. The eudemonic well-being tend to be associated with long-term and enduring effects.

Urban form impacts all three dimensions of well-being. For example, a short walk in a local park provides an immediate pleasure (hedonic); turning this behavior into a daily routine restores the mind from mental fatigue (psychological); and it also provides a great opportunity for social interaction with the neighbors (social). The known measurable impacts in this experience can be identified as: mood enhancement for hedonic well-being (Butryn and Furst, 2003), stress reduction (Ulrich, 1991) and cognitive restoration (Kaplan, 1995) for psychological well-being, and social connectedness for social well-being (Leyden, 2003). In other words, it is possible to suggest planning and design strategies that promote hedonic, psychological, and social well-being through interventions in urban form.

With this in mind, our research assessed the selected peer-reviewed articles. The results of such assessment, organized into the three types of mental well-being discussed above—hedonic, psychological, and social well-being—are presented in the next section.

Urban form and hedonic wellbeing

“Affect” is one of the key constructs to explain the relationship between urban form and hedonic well-being. As defined by Morris and Guerra (2015), affect is a measure of an individual’s transitory, moment-to-moment emotional state while an activity is undertaken. Measures of affect are typically latent variables composed of multiple measures of emotional states; they may be aggregated into a single affect score (Morris & Guerra, 2015), separate positive and negative affect scores (Nisbet & Zelenski, 2011), or an array of affect categories, such as the Pleasure, Arousal and Dominance dimensions suggested by Mehrabian and Albert (1980).

The majority of the literature seems to have focused on the relationship of affect and the natural environment. For instance, Kaplan (2001) conducted a study to examine how the view from an apartment window impacts the affect balance of residents. Affect elements were grouped into three composite measures: “effective functioning,” (including general attitude towards life), “at peace,” and “distracted.” These were then correlated with the presence of seven natural or nature-oriented features within the apartment’s viewshed: a garden or landscaped area, trees, a park, a large mowed area, a farm or field, a stream or river, and wildlife. It was found that gardens correlated with higher levels of effective functioning, trees correlated with higher levels of peace, and trees and fields correlated with lower levels of distraction. All other correlations occurred at insignificant levels. Nisbet and Zelenski (2011) found that university students who walked along an outdoor path in an urbanized nature area showed significantly higher positive affect and lower negative affect than those walking along an indoor path.

A considerable number of publications deal with environmental variables such as lighting, noise, temperature and color, mostly for indoor spaces in hospitals, schools, and work places. Differences in mood under different kinds of lighting in relation to gender and age were studied by Kenz and Kers (2000). Preference for colors has been associated with mood differences between males and females, although the evidence is conflicting (Camgöz et al., 2003; Rosenstein, 1985; Read et al., 1999). We found only three studies dealing with the impact of environmental variables on hedonic well-being at the urban scale. Air pollution (real and perceived) was found to be related to lower levels of happiness (Levinson, 2012; Li et al., 2014), and noise annoyance was found to be related to peaks and to the type of noise (Dockrell & Sheild, 2004).

The impact of urban form qualities on affects is an understudied topic. In a study of viewsheds from apartments, Kaplan (2001) correlated eight built elements (quiet street, busy street, sidewalk, vacant lot, houses, nonresidential buildings, fence or wall, and parking/people) with three aggregate measures of affect (effective functioning, at peace, and distracted). She found a positive correlation between having a quiet street in an apartment’s viewshed and feelings of effective functioning, although all other relationships between built elements and affect measures were insignificant. A pilot study by Hollander and Foster (2016) investigated the impact of Traditional Neighborhood Design (TND) features on mental state. Five participants used portable electro-encephalography monitors as they walked through two neighborhoods. The study suggested that higher TND scores may correlate with higher levels of attentiveness and meditation.

Transportation seems to have a significant impact on hedonic well-being. For instance, Olsson et al. (2013) found that satisfaction with the commute had a substantial positive impact on affect balance, and that active transportation (walking and cycling) correlated with higher satisfaction than by car or public transit. Morris and Guerra (2015), examining the relationship between commute modes and an affect balance index, used multiple models to compare commutes by car (driver), car (passenger), bus, train, walking, and bicycle. Car drivers and passengers were found to have higher affect balance scores, while pedestrians and bus passengers had lower scores. This finding is not supporting what was found in Olsson et al. (2013), which can be due to different neighborhood and transportation conditions. However, cyclists were found to have a much higher affect balance than all other modes, but significance could not be established due to the very small number of cycling trips in the sample.

Urban form and psychological wellbeing

Among the titles included in our investigation, studies on the relationship between psychological well-being and urban form were found to concentrate on three concepts: stress reduction, cognitive enhancement, and overall life satisfaction.

Several studies —some considered classics in environmental psychology —have demonstrated the restorative potential of natural environments in reducing stress (Ulrich, 1986; Ulrich et al., 1991; Ulrich, 1993), promoting recovery from attentional fatigue (Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan, R., 2001; Kaplan, S., 2001; Staats et al, 2003), and even improving overall health (Laumann, Gärling & Stormark, 2003). Several studies indicate that certain environments help psychological restoration by reducing both attentional fatigue and stress levels (Hartig et al. 2003, Hartig, Mang & Evans 1991, Ulrich et al. 1991). The potential of natural environments has been described by two theoretical strains rooted in psychological restoration: Stress Recovery Theory (SRT; Ulrich 1986) and Attention Restoration Theory (ART; Kaplan 1995). SRT is concerned with affective recovery from stress, while ART involves four components: a) being away from everyday thoughts and concerns, b) fascination (interest that is easily and effortlessly engaged), c) extent (or connectedness), and d) compatibility between individual’s needs and the actions required by the environment.

The high restorative potential of nature is confirmed by research reporting the positive health benefits of views or access to urban parks and natural settings for city residents. Visiting nature offers relief from stress, according to 95% of respondents in a nationwide survey of urban dwellers in the Netherlands, (Frerichs, 2004), and urban dwellers prefer being in park-like settings over being at home, in the city center, or riding transit when experiencing attentional fatigue (Staats, van Gemerden & Hartig, 2010). Urban green spaces that are rich in species and can act as a refuge were found to be preferred by stressed individuals Grahn & Strgsdotter (2009). Small pocket parks seem to have a similar restorative quality as larger regional parks if they are designed with a high degree of “naturalness” as measured by the amount of grass and tree coverage within the space, as shown for the case of Norwegian cities (Nordh, Hartig, Hagerhall & Fry, 2009).

When the exposure to urban nature is limited, the perception of elements perceived as natural has a positive restorative effect. Urban residents prefer the presence of street trees (Kalmbach & Kielbaso, 1979; Sommer, Guenther & Barker, 1990; Wolf, 2009) and the presence of flowers in streetscapes has been reported as more restful by the participants of a study by Todorova et al. (2004). Green roofs also have restorative effects (White & Gatersleben 2011) and promote affective recovery (Lee, Williams, Sargent, Williams, and Johnson 2015).

Although most studies indicate that natural environments have greater restorative potential than urban environments (Hartig et al., 2003; Herzog et al., 1997; Ulrich et al. 1991), it appears that certain urban settings have a restoration potential that is equivalent to or greater than natural environments (Herzog et al., 2003; Nasar & Terzano, 2010; van den Berg, Jorgensen & Wilson, 2014). The most important factors affecting psychological well-being in urban settings negatively were found to be noise, over-crowding, and fear of crime (Guite, Clark & Ackrill, 2006).

Urban public gathering spaces, such as plazas, have also been evaluated for their restorative potential. Abdulkarim and Nasar (2014), for instance, found that Whyte’s (1980) fundamental elements for public open spaces––seating, triangulation, and food––contributed to the restorativeness of the plazas included in their study. Hidalgo et al. (2006) discovered that historic-cultural and recreational public spaces had the greatest restoration potential that other types of urban settings, besides finding a correlation between the “attractiveness” of urban environments and their restorative potential.

A strain of research has investigated the role of architectural characteristics in promoting psychological restoration. Galindo & Hidalgo (2005) found that openness in built environments can positively affect the probability of restoration, Stamps (1999; 2005) showed that physical components of a building’s form can influence preference in urban settings, and Lindal and Hartig (2013) found that architectural variation (entropy) had a positive effect on restoration potential while building heights had a negative effect.

We found numerous studies on the relationship between different built environment attributes and subjective well-being, as a proxy for psychological or overall mental well-being. Stutzer and Frey (2007) define subjective well-being as “an individual’s evaluation of his or her experienced positive and negative affect, happiness or satisfaction with life.” Subjective well-being may be treated as a manifest variable measured by a single question--such as “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life these days?” (Bertram & Rehdanz, 2015)--or as a latent variable composed of multiple related questions--such as questions about matters relating to the subject’s happiness or satisfaction with life (Fassio, Rollero, & De Piccoli, 2013).

Several studies seek to understand the impacts of urban density, presence of nature, land use, housing, urban nuisances, and transportation in subjective well-being. Overall, evidence suggests there is either no or negative relationship between density and subjective well-being. Florida, Mellander and Rentfrow (2013) and Ambrey and Fleming (2014) found no correlation between density and life satisfaction. Fassio et al. (2013) found that residents of areas with a population density over 500 people per square kilometer scored lower than other respondents on three World Health Organization Quality of Life indices: psychological, social, and environmental quality of life. McCrea, Shyy, and Stimson (2006) found that perceived overcrowding correlates negatively with quality of life, and that objective density correlates significantly with both perceived overcrowding (positive) and quality of life (negative).

Overall, there is a clear, positive relationship between green space and psychological well-being, which does not exist between water and psychological well-being. Ambrey and Fleming (2014) suggested that a parcel’s proximity to rivers, lakes, and creeks showed no correlation with life satisfaction, and that while living at the coastline or up to three kilometers from it correlated positively with life satisfaction, greater distances showed no such correlation. Although, the same study found no significant correlation between the percentage of a district covered by green space (a neighborhood-level measure) and life satisfaction. White, Alcock, Wheeler, and Depledge (2013) found that while the percentage of neighborhood open space covered by green space had a positive impact on subjective well-being, no such correlation was found for the percentage of the neighborhood covered by water. Sugiyama et al. (2009) found that a parcel’s increasing distance from the nearest neighborhood open space correlated negatively on the study’s Satisfaction with Life Scale and that pleasantness of the neighborhood open space correlated with higher scores. Bertram and Rehdanz (2015) found that subjective well-being peaked at 35 hectares of green space within a one-kilometer buffer and a distance of 600 meters to the nearest green space.

The evidence on the impact of housing on psychological well-being seems to be much more limited and, sometimes, contradictory. Ambrey and Fleming (2014) and Bertram and Rehdanz (2015) found no significant relationship between housing type and subjective well-being, while White et al. (2013) found that residents of semidetached and terraced homes reported significantly higher subjective well-being than those of detached homes. This last study also showed that residents in flats showed lower stress levels than those residing in detached homes (measured through the General Health Questionnaire), and found no relationship between the number of rooms per resident and subjective well-being.

Literature is also relatively limited in regards to land use. Bertram and Rehdanz (2015) found no correlation between the number of schools per square kilometer and subjective well-being. Leyden, Goldberg and Michelbach (2011) measured the correlation between participants’ opinions on their cities’ amenities and levels of subjective well-being, aggregated at the city level. Cities whose residents reported adequate access to libraries and to culture and leisure facilities also reported higher levels of subjective well-being, but no correlation was found with opinions on access to shopping, parks and sports facilities. Leyden et al. (2011) found a positive correlation between perception of convenient access to transit stops and subjective well-being at the city level.

McCrea et al. (2006) found that the relationship between objective access to amenities (a latent variable composed of the distance to schools, shopping centers, sports facilities, and hospitals) and quality of life was fully mediated by subjective access to amenities as measured in a survey; in other words, objective access to amenities has direct impact on quality of life, only if, the perception of access also exists. In this case, the results of the relevant studies are in agreement: while real proximity to amenities has no or weak impact on subjective well-being, the perceived accessibility does.

Overall, nuisance elements appear to have a weak but negative impact on subjective well-being. Ambrey and Fleming (2014) found that living within three kilometers of an airport related negatively to life satisfaction while living from three to ten kilometers from an airport, within ten kilometers of a railway, and within three kilometers of a major road had no relationship. While studying elderly adults, Sugiyama et al. (2009) found that the perceived safety of neighborhood open space correlated positively with the scores of a Satisfaction With Life Scale survey while nuisance such as trash in neighborhood open space and the quality of paths to get to them had no correlation with such scores.

While the evidence is mixed, longer commutes have either a neutral or negative correlation with subjective well-being. Commute time at the city level was found by Florida et al. (2013) to have no correlation with Gallup-Healthways Well-being Index scores. White et al. (2013) found that commutes of over 50 minutes had a positive correlation with General Health Questionnaire scores, indicating lower well-being. Olsson et al. (2013) found a negative correlation between commute time and the Satisfaction with Travel Scale, which itself correlated positively with both the Satisfaction with Life Scale and the Affect-Balance Index. Stutzer and Frey (2007) found a negative correlation between commute time and subjective well-being and Ambrey and Fleming (2014) found a negative correlation between commute time and life satisfaction.

Urban form and social wellbeing

Urban form plays multiple roles in the perceived and objective social environment, and the social environment has an impact on the social-well-being of individuals. Features of social environments that may operate as stressors, such as perceptions of safety and social disorder, have been linked to mental well-being, as have factors that could buffer the adverse effects of stress, such as social cohesion and social capital (Mair et al., 2008). Social participation and integration in the immediate social environment are important to both mental and physical health (De Silva et al., 2005). Other important aspects include the stability of social connections, such as the existence of stable and supportive local social environments or neighborhoods in which to live and work.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified the social elements of mental well-being as social acceptance, beliefs in the potential of people and society as a whole, personal self-worth and usefulness to society, and sense of community (CDC, 2016). There are several related terms for the various components of social well-being: social capital, social connectedness, and social cohesion. Social capital is a form of economic and cultural capital in which social networks are central, and transactions are marked by reciprocity, trust and cooperation (Hassen & Kaufman, 2016). Social connectedness is the experience of belonging and relatedness between people (Dictionary.net, n.d.). At an individual level, social connectedness involves the quality and number of connections one has with other people in a social circle of family, friends, and acquaintances (De Silva et al., 2005). Social cohesion is the degree to which those in a social system identify with it and feel bound to support it, especially its norms, beliefs, and values (Bjornstrom & Ralston, 2014). A cohesive society works toward the well-being of all its members, fights exclusion and marginalization, creates a sense of belonging, promotes trust, and offers its members the opportunity of upward mobility.

The majority of articles, looked at social connectedness variables as they relate to the mental well-being variables and other social environment variables at the neighborhood level. For example, one study found that perceptions of social cohesion and social order are associated with greater levels of neighborhood satisfaction, whereas perceptions of neighborhood social support have no effect on satisfaction (Dassopoulos & Monnat, 2011). Social cohesion was also found to increase both the perception of neighborhood safety and self-rated health (De Jesus, Puleo, Shelton & Emmons, 2010; Poortinga, 2012). On the other hand, a deprived neighborhood leads to both a decrease in social cohesion and self-rated health (Poortinga, 2012). One of the studies also found that social support had a positive impact on females’ perception of neighborhood safety, but had no effect on males’ perception (De Jesus, Puleo, Shelton & Emmons, 2010). The authors also found that social networks had the reverse impact: males’ perception of neighborhood safety increased while there was impact on females’ perception of safety (De Jesus, Puleo, Shelton & Emmons, 2010). At the individual level, Bjornstrom & Ralston (2016) demonstrate that perceived danger and concentrated disadvantage have strong negative correlations with perceived cohesion, regardless of the objective built environment characteristics. Participation in a local business or civic group was found to increase self-rated health but had no impact on neighborhood satisfaction (Poortinga, 2012; Dassopoulos, & Monnat, 2011). Volunteering, however, was found to positively impact neighborhood satisfaction (Dassopoulos, & Monnat, 2011).

Community attachment theories suggest that perceptions of cohesion within one’s neighborhood are important because solidarity becomes a resource to effect positive change through both formal and informal community organizing and problem solving (Dassopoulos & Monnat, 2011). Referring back to the U.S. Center for Disease Control’s definition, one of the aspects of an individual in a state of mental well-being includes the ability to make a contribution to his or her community. This makes the linkage between social well-being and community participation, an important facet of planning that has urban design implications. The following paragraphs discuss the role of urban form in promoting social connectedness and individuals’ social well-being.

King (2013) found that increasing proportions of large building types are associated with increasing negative social relations (social cohesion, social capital and neighborliness) compared to single-unit housing. Diversity in housing age had a positive impact on social cohesion, social capital and neighborliness (King, 2013). When examining the timing of construction, recent construction was found to negatively impact social control. A literature review of eleven urban design element found that mixed tenure of residents had no impact on sense of community; however, it facilitates desirable places to live in the longer term which can allow social capital to grow (Paranagamage, Austin, Price, & Khandokar, 2010). Another study found no relationship between length of residency and sense of community (Wilkerson, Carlson, Yen, & Michael, 2016).

Bjornstrom & Ralston (2016) examined the ways that certain urban form characteristics at the neighborhood scale are associated with experienced social cohesion and how concentrated disadvantage and perceived danger moderate the relationships. They found that a neighborhood with a high prevalence of trees in a neighborhood perceived to be dangerous led to a decrease in social cohesion, whereas a high prevalence of trees in a neighborhood perceived to be safe led to an increase in social cohesion.

A review of fifteen articles found that the availability of public space correlated with an increase in social capital (Hassen & Kaufman, 2016). The availability of public space was found to have no impact on sense of identity, however the authors found that an increase in local facilities led to an increased sense of community (English Partnerships and the Housing Corporation, 2000). Similar to the latter finding, Zhu (2015) found that the presence of communal space within a neighborhood increased community participation. Zhu and Fu (2016) looked at the use and appraisal of communal space in China across 39 urban neighborhoods. They found the appraisal of communal space had no impact on social capital or neighborhood participation, however increased neighborhood attachment. The actual use of communal space had no impact on neighborhood participation or neighborhood attachment, however increased social capital (Zhu & Fu, 2016).

In regards to land use, one study found that low mixed-use neighborhoods increased residents’ sense of community (Wood, Frank, & Giles-Corti, 2010). An increase in the “area ratio” of commercial spaces in a neighborhood had a positive impact on sense of community (Wood, Frank, & Giles-Corti, 2010). Another study demonstrated the residents' higher perceived access to key resources was associated with higher neighborhood participation (Richard et al., 2009). When looking at mixed-use in general, a literature review of eleven studies found that it increased happiness and sense of identity, which contributes to the growth of social capital (Paranagamage, Austin, Price, & Khandokar, 2010). In sum, the findings related to mixed-use facilities were contradictory. Some studies found that mixed-use has a negative impact on sense of community whereas others found that mixed-use facilitates social inclusion by attracting a wider population in age and ethnicity, offering employment opportunity, encouraging social exchange, building social capital, and contributing to reduced feelings of isolation and depression in communities.

Several studies looked at the social impacts of walkability and found mixed results. One study found no significant relationship between a walkability index and three sociability indicators: social interaction, social cohesion and social control. One study found no impact on social capital (Sander, 2002). However a positive relationship was found with sense of community for younger but not older respondents (Toit, Cerin, Leslie, & Owen, 2007). Walkability was found to have a strong positive association with community engagement and sense of community (Renalds, Smith & Hale, 2010; Paranagamage, Austin, Price, & Khandokar, 2010). Another found that sense of community was positively associated with walking, but only leisure walking, not brisk (for transport) walking (Toit, Cerin, Leslie & Owen, 2007). At the block level, streets with more than 90% sidewalk connectivity had a significant positive impact on social cohesion (Wilkerson, Carlson, Yen, & Michael, 2016). The prevalence of sidewalks in a high disadvantaged neighborhood led to an increase in social cohesion in neighborhoods perceived both dangerous and safe. Bjornstrom and Ralston (2016) also looked at the prevalence of sidewalks in a low disadvantaged neighborhood in a perceived safe neighborhood and found no impact on social cohesion, while when in a perceived dangerous neighborhood, the prevalence of sidewalks decreased social cohesion. They interpret this result as the extent to which sidewalks facilitate cohesion in high-disadvantage neighborhoods is weakened by perceived danger.

In regards to transportation, one study found that transportation options offering a sense of mobility led to an increase in social cohesion (Ottoni, Sims-Gould, Winters, Heijnen, & McKay, 2016). At the block level, traffic-calming devices had no impact on social cohesion (Wilkerson, Carlson, Yen, & Michael, 2016). Additionally, walkability had no significant impact on social interaction, which in turn had no significant impact on sense of community.

Examining a smaller scale, spaces and enclosures with moderate openness without visual and acoustic distraction are the most desirable to promote pro-social behaviors (social participation; i.e., observing, smiling, laughing, and being physically active) among older adults with dementia and young children (Cerruti & Shepley, 2016). The visibility of neighbors led to the increased sense of community (Wood, Frank, & Giles-Corti, 2010).

Hochschild (2015) examined the difference in street types and found that different types of cul-de-sacs effect neighborly interconnectedness in different ways. The study found that neighbors living on bulb cul-de-sacs experience greater social cohesion than those on dead-end cul-de-sacs and through streets. Additionally, the shared social space, lack of outsiders and sense of territoriality on bulb and dead-end cul-de-sacs promote stronger neighborly ties than through streets. One article studied New Urbanist design attributes and found that houses without gates and that are marked by clear edges showed no significant relationship to social capital (Sander, 2002). The presence of bars on some windows had no impact on social cohesion, while residences with front porches led to an increase in social cohesion (Wilkerson, Carlson, Yen, & Michael, 2016). At the neighborhood level, one study found the availability of benches along the street positively contributed to older adults’ mobility, social cohesion and social capital (Ottoni, Sims-Gould, Winters, Heijnen, & McKay, 2016).

At the parcel level, a semi-enclosed spatial configuration led to an increased social interaction between older adults and children (Cerruti & Shepley, 2016). The older children's prosocial behaviors were likely facilitated by specific design features such as adequate personal space, the perception of openness, and spaces that provide both prospect and refuge in relation to spatial enclosure (Cerruti & Shepley, 2016). At the block level, one study found that the availability of tables in parks led to an increase in social cohesion (Anderson, Ruggeri, Steemers, & Huppert, 2016).

2. A model to direct studies on urban form and mental well-being

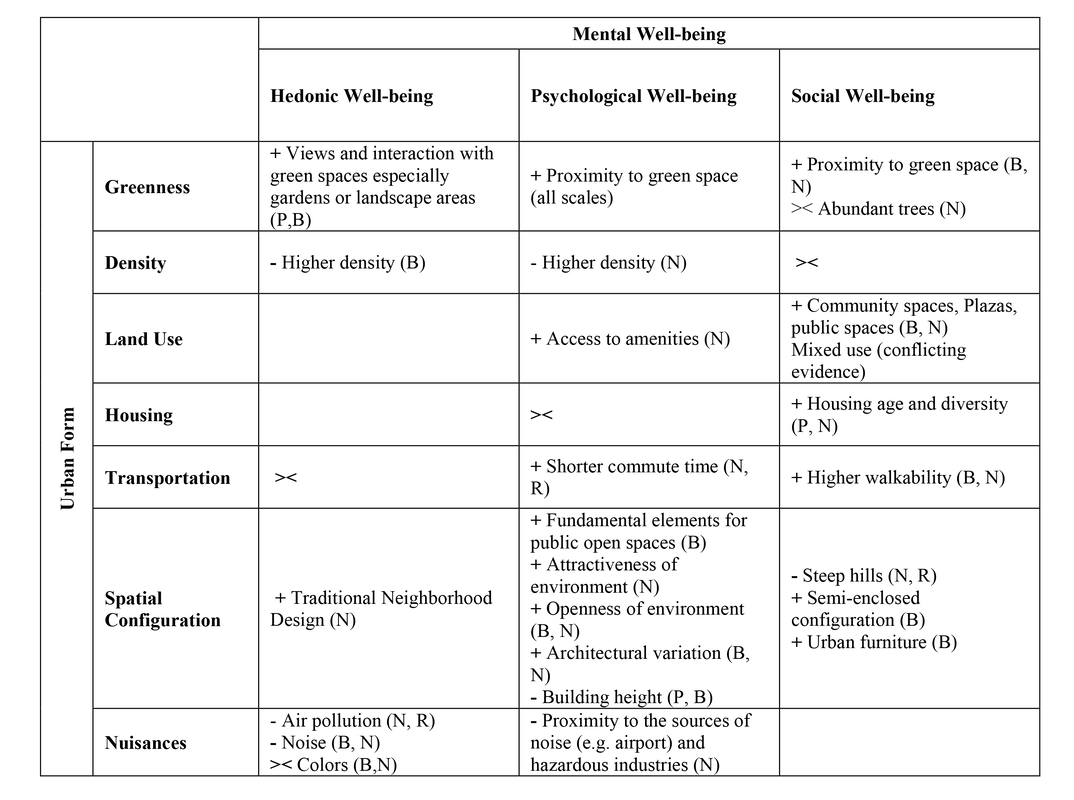

Our review of the existing literature revealed significant gaps, illustrated in Table 1. In some cases, these gaps result from contradictory information (for instance, the relationship between transportation mode and hedonic well-being), while in others, they result from studies that failed to find significant relationships (for instance, the relationship between housing type and psychological well-being). In other cases, the publication or study is absent of any data.

Table 1 The relationship of urban form and mental well-being; + positive correlation, - negative correlation, >< conflicting evidence;

Scale: Parcel à P, Block à B, Neighborhood à N, Region à R

Scale: Parcel à P, Block à B, Neighborhood à N, Region à R

As shown in Table 1, we identified eight potential reasons for the significant gap of evidence in the literature: 1) Methodological inconsistencies in measuring environmental qualities. This is particularly true for assessing environmental qualities that are ‘theoretical constructs’ (f.i. ‘walkable environment’ and ‘greenness’), and less of an issue for ‘observed variables’ (f.i. ‘floor-area ratio’ and ‘block-size’). For example, out of four studies that assessed the impact of ‘walkability’ on a psychological outcome, each utilized different measurement methods. 2) The unit of analysis or scale is another factor causing ambiguities. For example, the characteristics of urban form can be quantified at very different scales from the parcel to the city and to the region. ‘Density’ at the block-level does not necessarily have the same effect on well-being at the neighbourhood-level. 3) The potential mismatch between objective and perceived measures. For example, a survey of adult residents in Portland, Oregon found a mismatch between perceptions and objective measures of the environment, and suggest that factors such as socio-demographics, attitudes, social environment, and behaviour contribute to this mismatch and that the perceived and the objective environments have independent effects on behavioural patterns (Ma, 2014). Therefore, it seems that planning instruments that are solely based on perceived measures, such as the Happiness Index (Musikanski et al, 2017), may fall short in noticing the potential independent –or possibly contradictory- impacts of objective measures.

Other significant factors are 4) the complexity in distinguishing direct from indirect impacts of the environment on mental well-being through different behavioural and psychological mechanisms; 5) the potential mismatch between objective measures of well-being and subjective measures of happiness and life satisfaction; 6) the number of psychological variables directly or indirectly related to mental well-being, such as depression, anxiety, life satisfaction, and place-attachment; 7) inadequately controlling for individual and socio-economic characteristics in models that estimate the impact of urban form; and 8) the geographical, contextual, and demographic variations that need to be recognized before generalizing the conclusions.

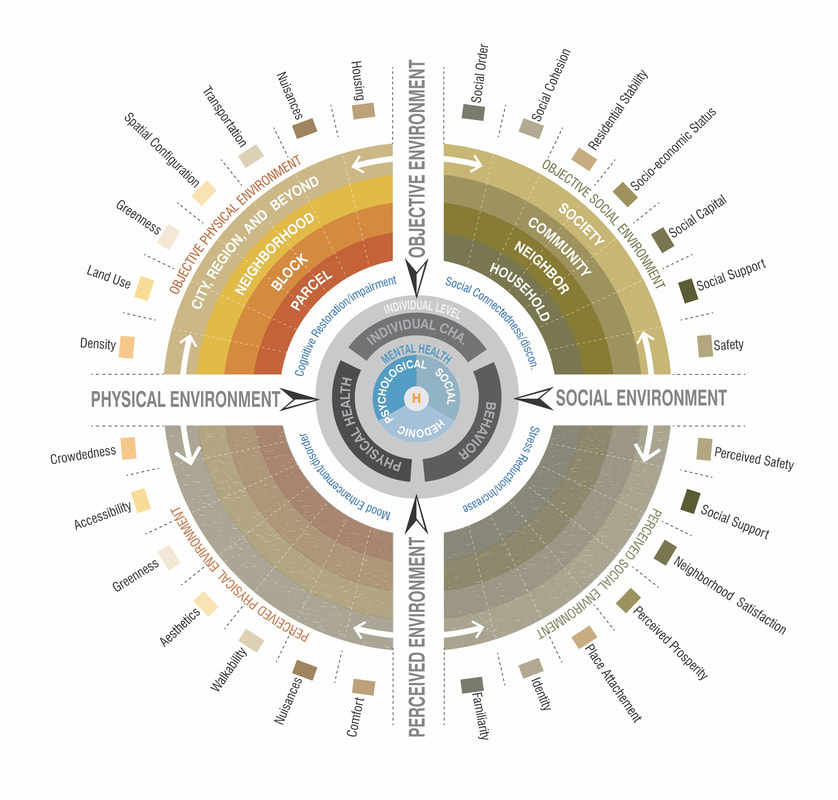

In order to help overcome these complications, and direct further studies in an organized manner, and fill in the gaps in the literature, we developed a conceptual framework to represent the impact of urban form on mental well-being. We were inspired by Larco’s (2016) sustainability framework for urban design where he categorized urban design elements and topics by scale as a basis for comparison and synergy. His model helps to understand the multi-layered consequences of urban form. We modified Larco’s model substantially in order to address the complex, multidimensional nature of mental well-being impacts by different factors and in different environments and scales (Figure 1).

Other significant factors are 4) the complexity in distinguishing direct from indirect impacts of the environment on mental well-being through different behavioural and psychological mechanisms; 5) the potential mismatch between objective measures of well-being and subjective measures of happiness and life satisfaction; 6) the number of psychological variables directly or indirectly related to mental well-being, such as depression, anxiety, life satisfaction, and place-attachment; 7) inadequately controlling for individual and socio-economic characteristics in models that estimate the impact of urban form; and 8) the geographical, contextual, and demographic variations that need to be recognized before generalizing the conclusions.

In order to help overcome these complications, and direct further studies in an organized manner, and fill in the gaps in the literature, we developed a conceptual framework to represent the impact of urban form on mental well-being. We were inspired by Larco’s (2016) sustainability framework for urban design where he categorized urban design elements and topics by scale as a basis for comparison and synergy. His model helps to understand the multi-layered consequences of urban form. We modified Larco’s model substantially in order to address the complex, multidimensional nature of mental well-being impacts by different factors and in different environments and scales (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework of the Relationship Between Urban Form and Mental Well-Being

To construct the model, we first considered the two major environmental dimensions that affect mental well-being: the physical and the social dimensions. These have to be considered individually but also simultaneously as they are likely to influence each other. Next, we considered the objective and the perceived environments, and defined four quadrants or realms for our model: 1) the objective physical environment, 2) the perceived physical environment, 3) the objective social environment, and 4) the perceived social environment. Each of these realms includes four scales. The physical environment includes: parcel, block, neighborhood, and city and region. The social environment includes: household, neighbor, community (residents of a given neighborhood), and society (residents of a given city or region).

In addition, each realm is divided into seven major planning/design dimensions that impact mental well-being. These factors--whether confounding, mediating, or moderating factors in the relationship of environmental factors and mental well-being--are also considered in the analytical framework. We categorized them into three groups: 1) behavioral factors, 2) physical health factors, and 3) individual factors (such as age, gender, income, personality and family situation).

As shown in Figure 1, the multi-dimentional and multi-factorial impacts of urban form on mental well-being requires a relatively complex conceptual diagram. Our proposed diagram helps evaluate urban environments by scale (e.g. parcel, block, neighborhood, city), planning dimension (e.g. density, land use, greenness, transportation, housing, spatial configuration, nuisances), environment type (physical vs. social), and measurement type (objective vs. perceived). The biggest advantage of conceptualizing such framework is to illustrate the now-known relationships and predict some now-unknown relationships between urban form and mental well-being and guide further studies to fill in the gaps. Besides, the diagram helps us recognize the complexity of the planning and design process when considering implications for mental well-being.

In addition, each realm is divided into seven major planning/design dimensions that impact mental well-being. These factors--whether confounding, mediating, or moderating factors in the relationship of environmental factors and mental well-being--are also considered in the analytical framework. We categorized them into three groups: 1) behavioral factors, 2) physical health factors, and 3) individual factors (such as age, gender, income, personality and family situation).

As shown in Figure 1, the multi-dimentional and multi-factorial impacts of urban form on mental well-being requires a relatively complex conceptual diagram. Our proposed diagram helps evaluate urban environments by scale (e.g. parcel, block, neighborhood, city), planning dimension (e.g. density, land use, greenness, transportation, housing, spatial configuration, nuisances), environment type (physical vs. social), and measurement type (objective vs. perceived). The biggest advantage of conceptualizing such framework is to illustrate the now-known relationships and predict some now-unknown relationships between urban form and mental well-being and guide further studies to fill in the gaps. Besides, the diagram helps us recognize the complexity of the planning and design process when considering implications for mental well-being.

Conclusion

There is no consensus about the form of a happy city, one that provides the psychological well-being of its residents. The various authors reviewed here suggest various universal factors that may do that. One of the most recognized factors, for instance is that access to green space correlates consistently with higher levels of mental well-being. Other factors need further study, and special attention must be given to studies with contradictory results as they suggest different factors impacting mental wellbeing. Some expected relationships have been challenged by recent studies, and what we think we know, may prove to be a convenient semi-truth. Additionally, the relationship between mental well-being, perceived features of the built environment, and objective features of the built environment has yet to be fully understood. Although the complexity of the topic and lack of research in some areas has contributed to this ambiguity, recent developments in the cognitive sciences and in biomedical informatics will certainly generate advances in the studies between the built environment and mental well-being.

However, given the existing literature and the known facts, we seem to be far from a universal performance metric and from defining thresholds to assess urban environments through the lens of mental wellbeing. What we need, and that was the main purpose of this article, is a framework to illustrate the complex relationships between the different types of built-environments and the different dimensions of mental well-being. The model we propose serves this purpose and provides a guide or checklist for practitioners and future research. It is our hope that future studies will fill the gaps in our proposed model, and help clarify the relationships between various environmental factors and mental well-being. While there is value to further explore well-established topics (such as the relationship between green space and well-being of all types), it is our hope that our conceptual model can serve as a guideline to channel future research towards areas where the relationship between urban form and mental well-being needs to be better understood.