|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2018:5;15

|

Applying the concept of Root Shock to urban renewal plans for Charlotte's Marshall Park

Kacie Ward (1) and Erin Sharp Newton (2)

(1) Masters of Architecture student, Pennsylvania State University, USA

(2) NK Architects Healthcare Group in Morristown, New Jersey, USA

(1) Masters of Architecture student, Pennsylvania State University, USA

(2) NK Architects Healthcare Group in Morristown, New Jersey, USA

Introduction

With the growing interest in planning and designing cities for mental health and wellbeing, we must consider whether this type of investment in the mental health of particular urban populations could be happening at the expense of the health and prosperity of others.

This phenomenon of displacement of the diverse is nothing new. In her book “Root Shock,” Mindy Fullilove describes multiple examples throughout history where neighborhoods have been torn apart in the name of progress, and about the damaging effects this can have on a community’s mental health. She goes on to offers a unique description of urban renewal: “The problem the planners tackled was not how to undo poverty, but how to hide the poor. Urban renewal was designed to segment the city so that barriers of highways and monumental buildings protected the rich from the sight of the poor, and enclosed the wealthy center away from the poor margin.” (Fullilove 2016)

This phenomenon of displacement of the diverse is nothing new. In her book “Root Shock,” Mindy Fullilove describes multiple examples throughout history where neighborhoods have been torn apart in the name of progress, and about the damaging effects this can have on a community’s mental health. She goes on to offers a unique description of urban renewal: “The problem the planners tackled was not how to undo poverty, but how to hide the poor. Urban renewal was designed to segment the city so that barriers of highways and monumental buildings protected the rich from the sight of the poor, and enclosed the wealthy center away from the poor margin.” (Fullilove 2016)

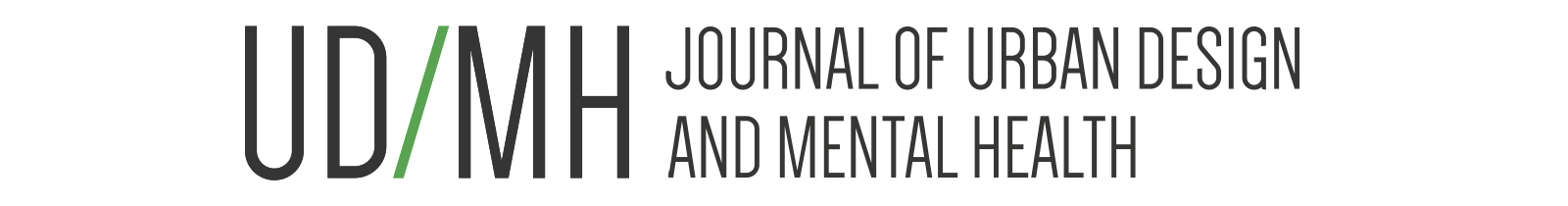

Figure 1. 1950’s Charlotte, Destruction of Homes in the Second Ward versus Urban Renewal Construction // The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Story/Charlotte-Mecklenburg Library (“Destruction of the Second Ward”)

In Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape, Francesca Russello Ammon references the origins of a “culture of clearance” as emerging after World War II. About 7.5 million dwelling units across the United States, on an average of one out of every 17 in the country, were demolished by wrecking crews between 1950 and 1980. Leading the charge was the bulldozer itself, which was promoted in equipment ads as a positive ideology of demolition-as-renewal. (Ammon 2016)

What effect does this sort of development have on the mental health and wellbeing of the people that are displaced? The CDC states:

“Where people live, work and play has an impact on their health. Several factors create disparities in a community’s health. Examples include socioeconomic status, land use/the built environment, race/ethnicity, and environmental injustice. In addition, displacement has many health implications that contribute to disparities among special populations, including the poor, women, children, the elderly, and members of racial/ethnic minority groups. These special populations are at increased risk for the negative consequences of gentrification. Studies indicate that vulnerable populations typically have shorter life expectancy; higher cancer rates; more birth defects; greater infant mortality; and higher incidence of asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.” (“Healthy Places” 2009)

A great example of this is the city of Charlotte, North Carolina, the second-largest city in the southeastern United States and the third-fastest growing major city in the United States. (Charlotte, North Carolina, 2018). Between 2004 and 2014, Charlotte was ranked as the country's fastest growing metro area and is now one of the top 20 most populated cities in the US (population 810,000). Based on U.S. Census data from 2005 to 2015, it also tops the 50 largest U.S. cities as the millennial hub.

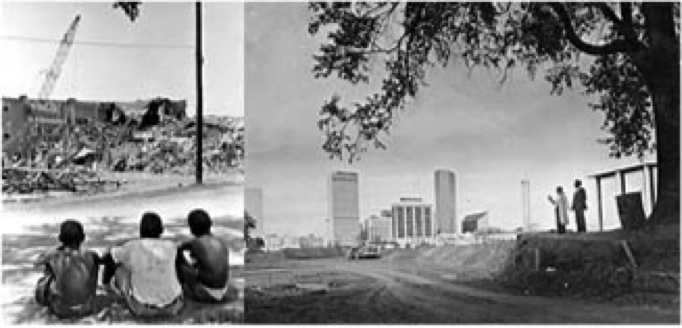

Charlotte’s center city has an identity that has evolved greatly over time. The issues of displacement, inclusion, exclusion, belonging, and identity within Charlotte can been seen in its changing name over time. Currently Downtown Charlotte is called “Uptown Charlotte”. Uptown was once called “Downtown.” Many people remember the city being rebranded with this name during the 1970’s. Memorialized in the City Clerk Minutes on September 23, 1974, page 449, the resolution was recorded as follows (“City Clerk”):

What effect does this sort of development have on the mental health and wellbeing of the people that are displaced? The CDC states:

“Where people live, work and play has an impact on their health. Several factors create disparities in a community’s health. Examples include socioeconomic status, land use/the built environment, race/ethnicity, and environmental injustice. In addition, displacement has many health implications that contribute to disparities among special populations, including the poor, women, children, the elderly, and members of racial/ethnic minority groups. These special populations are at increased risk for the negative consequences of gentrification. Studies indicate that vulnerable populations typically have shorter life expectancy; higher cancer rates; more birth defects; greater infant mortality; and higher incidence of asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.” (“Healthy Places” 2009)

A great example of this is the city of Charlotte, North Carolina, the second-largest city in the southeastern United States and the third-fastest growing major city in the United States. (Charlotte, North Carolina, 2018). Between 2004 and 2014, Charlotte was ranked as the country's fastest growing metro area and is now one of the top 20 most populated cities in the US (population 810,000). Based on U.S. Census data from 2005 to 2015, it also tops the 50 largest U.S. cities as the millennial hub.

Charlotte’s center city has an identity that has evolved greatly over time. The issues of displacement, inclusion, exclusion, belonging, and identity within Charlotte can been seen in its changing name over time. Currently Downtown Charlotte is called “Uptown Charlotte”. Uptown was once called “Downtown.” Many people remember the city being rebranded with this name during the 1970’s. Memorialized in the City Clerk Minutes on September 23, 1974, page 449, the resolution was recorded as follows (“City Clerk”):

Years before this formal change, when Charlotte was simply a few main trade routes through Trade Street and Tryon Street (still used by the Native Americans that originally inhabited this land), it was often referred to as “uptown” simply because of its geography. The center city area of Charlotte exists at a higher elevation than the surrounding area. Thus, going into town was often phrased as going “up to town” and later became “uptown.” (Wxbrad, 2014) Then in the late 1920s, the main newspaper of Charlotte – The Charlotte Observer – went from using “uptown” to “downtown”, at a time when “downtown” was the preferable term. (Canal) This could have been due to the industrial revolution, and an attempt to fit in with other major “downtowns” in cities throughout America. Looking closely at the way Charlotte advertises itself to the world, it appears to be quite concerned with fitting in, image, status, branding, and advertising.

Alongside the name change, in the 1950’s Charlotte began to embrace “downtown renewal.” Not revival, not rehabilitation, not rejuvenation – renewal, implying new. By the time the 1970s, came along, a clothing store owner by the name of Jack Wood decided to take Charlotte’s identity into his own hands. Jack had grown up in Charlotte and opened up a store there. As the “downtown” area became a place for shopping and socializing, Wood decided the word “downtown” was just too depressing to use as the descriptive name for such a vibrant young city. He believed Charlotte should be called “uptown” for a more positive identity. After petitioning and relentlessly writing letters to the newspaper – who at the time did not agree with Wood’s opinion, he eventually got what he wanted. (Canal) If “downtown” was depressing as a term, what would this mean to those who lived in the new “downtown”? Did this mean they no longer fit in? What impact did this have on their well-being? The answers can be imagined.

In looking at today’s image of this uptown city, the changing face of Charlotte appears to risk obscuring the identity of those who remain but do not fit into the latest “design”. This can be seen on the website of one of Charlotte’s popular museums is the Levine Museum of the New South, which celebrates the city’s history. Tom Hanchett, a well-known Charlotte historian, has written many paragraphs on the museum's site describing Charlotte’s evolvement as a “New South” city. He writes in selective detail about how Charlotte became the banking city it is today:

“Over the last 150 years we’ve moved from slavery to segregation to Civil Rights, from fields to factories to finance. But the one constant throughout this New South era has been an enthusiasm for re-inventing this place.” (Hanchett)

If there is “an enthusiasm for re-inventing” Charlotte, it can also feel like the city doesn’t really want to honor its history, but rather erase it, change it, or pretend it isn’t important. (Hanchett) How does this impact identity and mental health for those who are part of the history that can seem to be erased? Is that leaving a legacy of healing, community and equitable well-being? This particular erasure can be seen in one of the very large green spaces that is set for demolition and development:

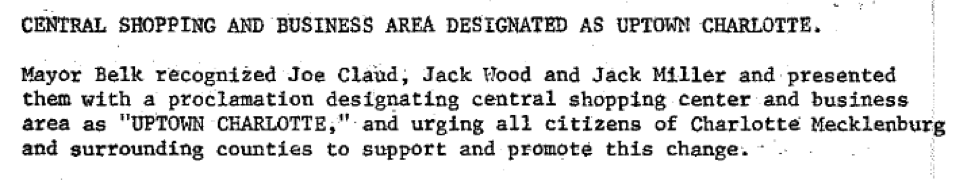

Marshall Park, a six-and-a-half acre urban park, has been used as a place for protests and demonstrations in Charlotte since the 1980’s, and is a great example of the effects of development on communities of diversity. (Portillo 2016) Soon this park is going to be destroyed and built over with more apartments and stores, mirroring the ones recently added to the Charlotte skyline. While many would call this growth in a young, developing city, many also choose to ignore the eradication that must first take place to make room for this growth. This demolition will be taking away the voice of the already almost voiceless communities of Charlotte.

Alongside the name change, in the 1950’s Charlotte began to embrace “downtown renewal.” Not revival, not rehabilitation, not rejuvenation – renewal, implying new. By the time the 1970s, came along, a clothing store owner by the name of Jack Wood decided to take Charlotte’s identity into his own hands. Jack had grown up in Charlotte and opened up a store there. As the “downtown” area became a place for shopping and socializing, Wood decided the word “downtown” was just too depressing to use as the descriptive name for such a vibrant young city. He believed Charlotte should be called “uptown” for a more positive identity. After petitioning and relentlessly writing letters to the newspaper – who at the time did not agree with Wood’s opinion, he eventually got what he wanted. (Canal) If “downtown” was depressing as a term, what would this mean to those who lived in the new “downtown”? Did this mean they no longer fit in? What impact did this have on their well-being? The answers can be imagined.

In looking at today’s image of this uptown city, the changing face of Charlotte appears to risk obscuring the identity of those who remain but do not fit into the latest “design”. This can be seen on the website of one of Charlotte’s popular museums is the Levine Museum of the New South, which celebrates the city’s history. Tom Hanchett, a well-known Charlotte historian, has written many paragraphs on the museum's site describing Charlotte’s evolvement as a “New South” city. He writes in selective detail about how Charlotte became the banking city it is today:

“Over the last 150 years we’ve moved from slavery to segregation to Civil Rights, from fields to factories to finance. But the one constant throughout this New South era has been an enthusiasm for re-inventing this place.” (Hanchett)

If there is “an enthusiasm for re-inventing” Charlotte, it can also feel like the city doesn’t really want to honor its history, but rather erase it, change it, or pretend it isn’t important. (Hanchett) How does this impact identity and mental health for those who are part of the history that can seem to be erased? Is that leaving a legacy of healing, community and equitable well-being? This particular erasure can be seen in one of the very large green spaces that is set for demolition and development:

Marshall Park, a six-and-a-half acre urban park, has been used as a place for protests and demonstrations in Charlotte since the 1980’s, and is a great example of the effects of development on communities of diversity. (Portillo 2016) Soon this park is going to be destroyed and built over with more apartments and stores, mirroring the ones recently added to the Charlotte skyline. While many would call this growth in a young, developing city, many also choose to ignore the eradication that must first take place to make room for this growth. This demolition will be taking away the voice of the already almost voiceless communities of Charlotte.

Figure 2. Map of Charlotte, NC, Marking Marshall Park as a “Protest Spot” // When Marshall Park goes away, where will Charlotte protesters gather?/The Charlotte Observer (Portillo 2017)

Marshall Park’s destruction echoes the fate of the neighborhood which came before it, known as “Brooklyn”. Home to 1,007 families and 216 businesses, this neighborhood, was torn down as a direct result of the city’s “urban renewal” agenda. (“Brooklyn’s Timeline”) The renewal plan displaced numerous families, giving them nowhere to relocate. This left families placeless by no fault of their own, finding they literally no longer belonged in their own city.

One only needs to imagine watching their house be torn down and being told they do not belong there, to imagine the impact on these people's self-esteem and sense of hope. Furthermore, as Fullilove explains in her book “Root Shock,” by tearing down these neighborhoods, we are also tearing down the very “interconnectedness” that people emotionally thrive on: “We–that is to say, all people–live in an emotional ecosystem that attaches us to the environment, not just as our individual selves, but as beings caught in a single, universal net of consciousness anchored in small niches we call neighborhoods or hamlets or villages.” (Fullilove 2016) By taking away this emotional infrastructure, we are damaging the emotional stability and mental health of those individuals relying on their everyday social interactions.

Helping to describe these vital social interactions, Fullilove references Jane Jacobs’ depiction of the “sidewalk ballet,” a term coined by Jacobs in her book Death and Life of Great American Cities. The passage begins with: “The stretch of Hudson Street where I live is each day the scene of an intricate sidewalk ballet.” Jacobs goes on to describe her morning routine and that of her neighborhoods, describing the comfortable repetitiveness of their intertwined lives. The passage ends with: “We have done this many a morning for more than ten years, and we both know what it means: All is well.” (Jacobs 2011)

This comfort and reliance upon routine social interactions with other people in ones neighborhood creates a mentally stable environment for those people to lead physically healthier lives. As described by the International Making Cities Livable group, “Long-time neighborhood residents commonly develop deep social ties and strong social support networks within the community. When the neighborhood and social connections therein are broken up, this ‘social loss’ creates excess stress and psychological effects, which in turn have effects on physical systems that we rely on for resilience against disease and chronic conditions. Cultural institutions, culturally relevant businesses and a general feeling of having a place in the city to call home provide many social and health benefits beyond the face value that we often find in the gentrification debate.” (“The Other Side…”) This “social loss,” a term from Fullilove’s book, is often overlooked by the city boards deciding which neighborhoods should be torn down.

Losing Marshall Park would be a “social loss” for many groups of people in Charlotte. If Marshall Park is destroyed, these diverse communities that once again considered this land their home will be reminded that in order for Charlotte to move forward, they must be left behind. Even if a new park is rebuilt, it is likely to be smaller than Marshall Park is now, currently the largest park in Charlotte’s center city area. (Portillo 2016) More to the point, it will be surrounded by apartments meant for the people that Charlotte is being built for. The diverse, lower class communities of Charlotte are not those people. By taking away this park of protests it sends the message that the voices and opinions of those who frequent the park are not important and have no place in the Charlotte of the future.

One only needs to imagine watching their house be torn down and being told they do not belong there, to imagine the impact on these people's self-esteem and sense of hope. Furthermore, as Fullilove explains in her book “Root Shock,” by tearing down these neighborhoods, we are also tearing down the very “interconnectedness” that people emotionally thrive on: “We–that is to say, all people–live in an emotional ecosystem that attaches us to the environment, not just as our individual selves, but as beings caught in a single, universal net of consciousness anchored in small niches we call neighborhoods or hamlets or villages.” (Fullilove 2016) By taking away this emotional infrastructure, we are damaging the emotional stability and mental health of those individuals relying on their everyday social interactions.

Helping to describe these vital social interactions, Fullilove references Jane Jacobs’ depiction of the “sidewalk ballet,” a term coined by Jacobs in her book Death and Life of Great American Cities. The passage begins with: “The stretch of Hudson Street where I live is each day the scene of an intricate sidewalk ballet.” Jacobs goes on to describe her morning routine and that of her neighborhoods, describing the comfortable repetitiveness of their intertwined lives. The passage ends with: “We have done this many a morning for more than ten years, and we both know what it means: All is well.” (Jacobs 2011)

This comfort and reliance upon routine social interactions with other people in ones neighborhood creates a mentally stable environment for those people to lead physically healthier lives. As described by the International Making Cities Livable group, “Long-time neighborhood residents commonly develop deep social ties and strong social support networks within the community. When the neighborhood and social connections therein are broken up, this ‘social loss’ creates excess stress and psychological effects, which in turn have effects on physical systems that we rely on for resilience against disease and chronic conditions. Cultural institutions, culturally relevant businesses and a general feeling of having a place in the city to call home provide many social and health benefits beyond the face value that we often find in the gentrification debate.” (“The Other Side…”) This “social loss,” a term from Fullilove’s book, is often overlooked by the city boards deciding which neighborhoods should be torn down.

Losing Marshall Park would be a “social loss” for many groups of people in Charlotte. If Marshall Park is destroyed, these diverse communities that once again considered this land their home will be reminded that in order for Charlotte to move forward, they must be left behind. Even if a new park is rebuilt, it is likely to be smaller than Marshall Park is now, currently the largest park in Charlotte’s center city area. (Portillo 2016) More to the point, it will be surrounded by apartments meant for the people that Charlotte is being built for. The diverse, lower class communities of Charlotte are not those people. By taking away this park of protests it sends the message that the voices and opinions of those who frequent the park are not important and have no place in the Charlotte of the future.

Figure 3. Photograph of a Tea Party Rally in Marshall Park in 2009 // When Marshall Park goes away, where will Charlotte protesters gather?/The Charlotte Observer (Portillo 2017)

By not giving particular communities a space within this development over which they feel a sense of ownership, these groups’ sense of belonging in the city is taken away by force. If people already feel discriminated against, excluding them in the development of the city that is their home adds to that sense of discrimination. Acts of discrimination and loss of community identity can have a negative impact on mental health. Discrimination exacerbates stress, anxiety and depression, in adults and children, according to an Impact of Discrimination campaign (American Psychological Associations 2015). Their research found people of colour more likely to report poorly maintained community/ recreational parks and facilities as a big or somewhat big problem, indicating the importance of providing better green space, not less.

Charlotte, with all its vibrancy in parts, and ever changing face, has great potential to grow in a more inclusive manner, which would benefit the vibrancy overall. By applying the most current research on the built environment factors affecting mental health, such as provision of green space and facilitues for physical activity and pro-social interaction, the development of Marshall Park is an opportunity for inclusiveness and mental health promotion for all. (Mind the GAPS Framework: The Impact of Urban Design and Mental Health and Wellbeing).

Charlotte, with all its vibrancy in parts, and ever changing face, has great potential to grow in a more inclusive manner, which would benefit the vibrancy overall. By applying the most current research on the built environment factors affecting mental health, such as provision of green space and facilitues for physical activity and pro-social interaction, the development of Marshall Park is an opportunity for inclusiveness and mental health promotion for all. (Mind the GAPS Framework: The Impact of Urban Design and Mental Health and Wellbeing).

References

American Psychological Associations 2015 Stress in America – The Impact of Discrimination.” Monitor on Psychology, American Psychological Association, 2015, www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2015/impact.aspx.

Ammon, Francesca Russello. Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape. Yale University Press, 2016.

Wxbrad. “Blog.” @Wxbrad Blog, Wxbrad Http://Wxbrad.com/Wp-Content/Uploads/2015/08/smalllogo2.Png, 19 Mar. 2014, wxbrad.com/why-its-called-uptown-why-charlottes-uptown-streets-go-northeast/

“Brooklyn Oral History.” Brooklyn Oral History, brooklyn-oral-history.uncc.edu/

“Brooklyn Oral History.” Brooklyn Oral History, UNC Charlotte, brooklyn-oral-history.uncc.edu/

“Brooklyn Time Line.” Brooklyn Oral History, UNC Charlotte, 7 Oct. 2016, brooklyn-oral-history.uncc.edu/historic-sources/brooklyn-time-line/

Canal, Nick de la. “FAQ City: Why Is Downtown Charlotte Called 'Uptown'?” WFAE, wfae.org/post/faq-city-why-downtown-charlotte-called-uptown#stream/0

“Charlotte, North Carolina.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 June 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte,_North_Carolina

“Charlotte, North Carolina Population 2018.” China Population 2018 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs), worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/charlotte-population/

“City Clerk.” City of Charlotte Government, charlottenc.gov/CityClerk/Pages/Ordinances.aspx

Destruction in the Second Ward. Digital image. <i>Brooklyn 1950’s<i>. N.p., n.d. Web. <http://www.cmstory,org/aaa2/places/content_brooklyn.htm> [an image of construction in the Second Ward of Charlotte]

Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Root Shock: How Tearing up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do about It. New Village Press, 2016

Hanchett, Thomas W. “Welcome to Charlotte!” History South, www.historysouth.org/welcome-to-charlotte/

“Healthy Places.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009, www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/healthtopics/gentrification.htm

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Modern Library, 2011

Markovich, Jeremy. “Marshall Park Is Terrible.” Charlotte at Home Ch, 3 Mar. 2014, www.charlottemagazine.com/Blogs/Way-Out/February-2014/Marshall-Park-is-Terrible/

“Mind the GAPS Framework.” Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, www.urbandesignmentalhealth.com/mind-the-gaps-framework.html

Pam Kelley Feed Pam Kelley, and Charlotte Observer. “Old Anger and a Lost Neighborhood In Charlotte.” CityLab, 11 Oct. 2016, www.citylab.com/equity/2016/10/old-anger-and-a-lost-neighborhood-in-charlotte/503627/

Portillo, Ely. “Marshall Park Is on Its Way out – but Will New Development Have Enough Park Space?” Charlotteobserver, Charlotte Observer, 16 Aug. 2016, www.charlotteobserver.com/news/business/biz-columns-blogs/development/article95173087.html

Portillo, Ely. “When Marshall Park Goes Away, Where Will Charlotte Protesters Gather?” Charlotteobserver, Charlotte Observer, 4 May 2017, www.charlotteobserver.com/news/business/biz-columns-blogs/development/article148478909.html

“The Other Side of Gentrification: Health Effects of Displacement.” What Makes a Healthy, 10-Minute Neighborhood? | International Making Cities Livable, www.livablecities.org/blog/other-side-gentrification-health-effects-displacement

Ammon, Francesca Russello. Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape. Yale University Press, 2016.

Wxbrad. “Blog.” @Wxbrad Blog, Wxbrad Http://Wxbrad.com/Wp-Content/Uploads/2015/08/smalllogo2.Png, 19 Mar. 2014, wxbrad.com/why-its-called-uptown-why-charlottes-uptown-streets-go-northeast/

“Brooklyn Oral History.” Brooklyn Oral History, brooklyn-oral-history.uncc.edu/

“Brooklyn Oral History.” Brooklyn Oral History, UNC Charlotte, brooklyn-oral-history.uncc.edu/

“Brooklyn Time Line.” Brooklyn Oral History, UNC Charlotte, 7 Oct. 2016, brooklyn-oral-history.uncc.edu/historic-sources/brooklyn-time-line/

Canal, Nick de la. “FAQ City: Why Is Downtown Charlotte Called 'Uptown'?” WFAE, wfae.org/post/faq-city-why-downtown-charlotte-called-uptown#stream/0

“Charlotte, North Carolina.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 June 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte,_North_Carolina

“Charlotte, North Carolina Population 2018.” China Population 2018 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs), worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/charlotte-population/

“City Clerk.” City of Charlotte Government, charlottenc.gov/CityClerk/Pages/Ordinances.aspx

Destruction in the Second Ward. Digital image. <i>Brooklyn 1950’s<i>. N.p., n.d. Web. <http://www.cmstory,org/aaa2/places/content_brooklyn.htm> [an image of construction in the Second Ward of Charlotte]

Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Root Shock: How Tearing up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do about It. New Village Press, 2016

Hanchett, Thomas W. “Welcome to Charlotte!” History South, www.historysouth.org/welcome-to-charlotte/

“Healthy Places.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009, www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/healthtopics/gentrification.htm

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Modern Library, 2011

Markovich, Jeremy. “Marshall Park Is Terrible.” Charlotte at Home Ch, 3 Mar. 2014, www.charlottemagazine.com/Blogs/Way-Out/February-2014/Marshall-Park-is-Terrible/

“Mind the GAPS Framework.” Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, www.urbandesignmentalhealth.com/mind-the-gaps-framework.html

Pam Kelley Feed Pam Kelley, and Charlotte Observer. “Old Anger and a Lost Neighborhood In Charlotte.” CityLab, 11 Oct. 2016, www.citylab.com/equity/2016/10/old-anger-and-a-lost-neighborhood-in-charlotte/503627/

Portillo, Ely. “Marshall Park Is on Its Way out – but Will New Development Have Enough Park Space?” Charlotteobserver, Charlotte Observer, 16 Aug. 2016, www.charlotteobserver.com/news/business/biz-columns-blogs/development/article95173087.html

Portillo, Ely. “When Marshall Park Goes Away, Where Will Charlotte Protesters Gather?” Charlotteobserver, Charlotte Observer, 4 May 2017, www.charlotteobserver.com/news/business/biz-columns-blogs/development/article148478909.html

“The Other Side of Gentrification: Health Effects of Displacement.” What Makes a Healthy, 10-Minute Neighborhood? | International Making Cities Livable, www.livablecities.org/blog/other-side-gentrification-health-effects-displacement

About the Authors

|

Kacie Ward has a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and is currently working towards her Masters of Architecture at Pennsylvania State University (Class of 2020). Her areas of interest include healthcare architecture with a focus on humanity and wellness.

|

|

Erin Sharp Newton is part of the NK Architects Healthcare Group in Morristown, New Jersey in the US. She holds a Master’s Degree in Architecture from UCLA and a Master’s in Design from Domus Academy in Milan, Italy. Erin has lived and worked in Los Angeles, Milan, Philadelphia and New Jersey. Her exposure and experience span all areas of design, from architecture to the fine arts, from industrial design to technology, and her research and ideas have featured in venues such as Philips Solid Side and the Milan Design Fair. She is an Associate Member of the American Institute of Architects, a Board Member of the Hunterdon Drug Awareness Program, and is on two Health & Human Services Local Advisory Committees. Erin believes that integrity and creativity are fundamental to the success of the multi-faceted world of design and living. Erin is a UD/MH Fellow.

|