|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2018:5;14

|

Designing neighbourhoods for quality of life and mental wellbeing: exploring opportunities for Rohini, Delhi

Kriti Agarwal

Architect and urban designer at We Design, Delhi, India

Architect and urban designer at We Design, Delhi, India

Introduction

Delhi, the capital city of the culturally rich country of India, shoulders the responsibility of ensuring continuity and prosperity in a secular manner. Delhi being a mega city also faces the issues of migrants coming in from the not-so-developed parts of the country for better job opportunities. To accommodate the increasing population the city is expanding and urbanizing the agricultural land along its periphery. These areas have existing settlements known as urbanized villages as well as ‘unauthorized colonies’. While the immigrants are faced with the challenge of creating a place for themselves in the new society, the original inhabitants who have been engaged in agriculture and associated activities so far, not only face social issues but also the loss of livelihood.

Greater isolation, increased aggression, heightened mistrust and hostility is prevalent, with the residents’ daily activities being inhibited by fear of crime and violence, resulting in no peace of mind of souls made weary by exploitation. Traffic, crime and pollution make reluctant metropolitans out of most inhabitants. Anthony Downs claims that the physical condition of a city’s residential neighbourhoods, which contain much of its territory and most of its population, has an important bearing on the overall health of the city. (Downs). These issues though more prevalent in Delhi, are seen in other Indian cities as well. The Times of India-IMRB Quality of Life survey conducted in 2011 highlights that the cities of Ahmedabad, Pune, Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Chennai and Kolkatta were all rated below average by the people (Times of India). The parameters were Physical & Civic Infrastructure, Commuting Ease, Peace of Mind, Social Infrastructure, Environment, Leisure Facilities, and Social and Cultural Values.

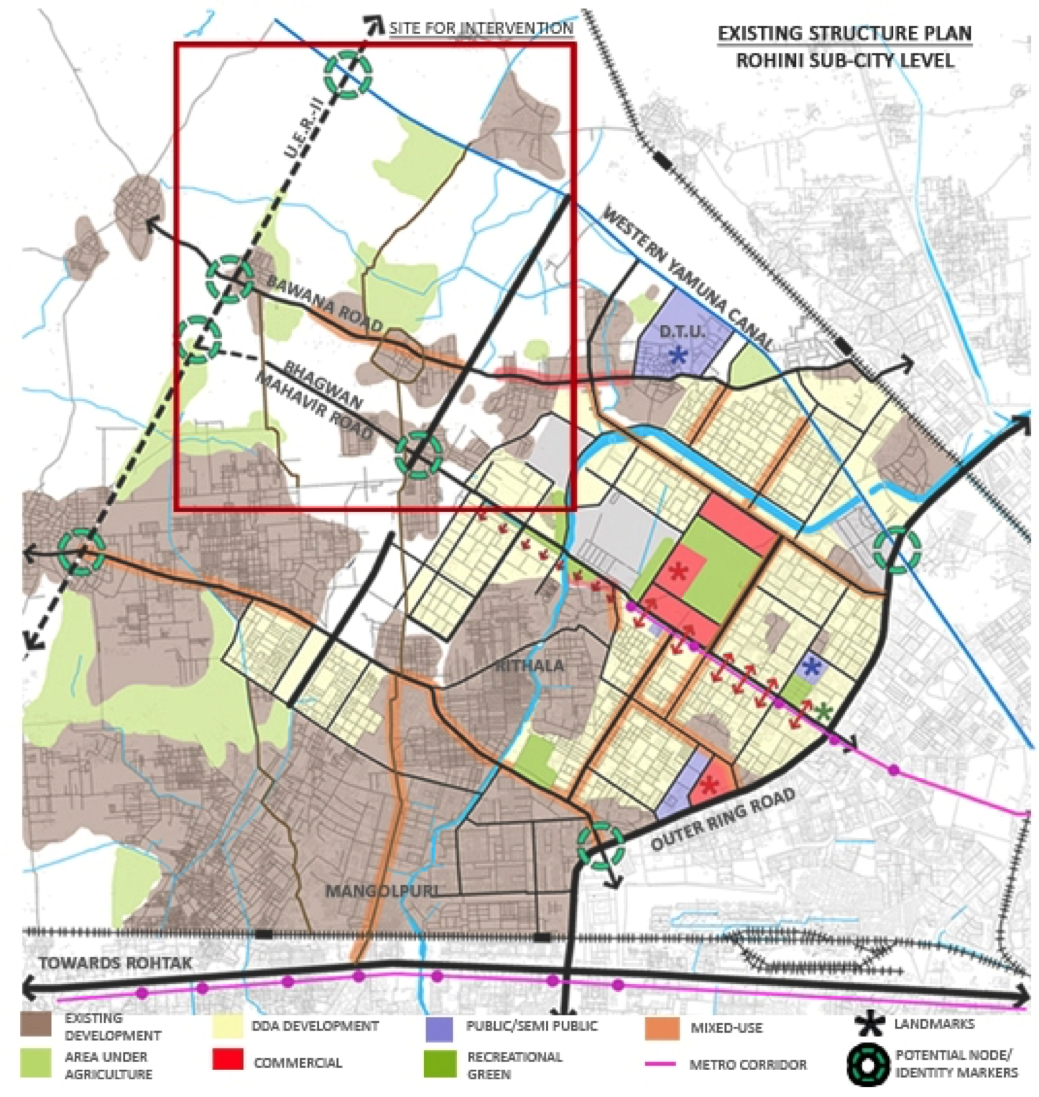

While the Master Plans of Delhi which guide the cities development, illustrate the strategy for accommodating the vast number of migrants into the city, a strategy for providing a decent standard of living through the design of the physical environment is missing. This case study is based in the urban extension area of Rohini Sub-city first proposed in the Master Plan of Delhi 2001 to be built in five phases, mandating conversion of peripheral agricultural land into urban area. Rohini is well connected to rest of the city by both MRTS and bus systems. City level educational institutes and health facilities are also located here

Phases 4 and 5 of the sub-city are yet to be developed. The planning of the sub-city follows a rubber-stamp approach where a standard pre-designed sector-layout has been blindly proposed to cover the entire land area available. The Zonal Development Plan for Rohini too fails to consider the existing areas with the new development proposed with its back to these areas thereby creating a divide and tension between the two. This speculative case study considers the opportunities to rectify this.

Greater isolation, increased aggression, heightened mistrust and hostility is prevalent, with the residents’ daily activities being inhibited by fear of crime and violence, resulting in no peace of mind of souls made weary by exploitation. Traffic, crime and pollution make reluctant metropolitans out of most inhabitants. Anthony Downs claims that the physical condition of a city’s residential neighbourhoods, which contain much of its territory and most of its population, has an important bearing on the overall health of the city. (Downs). These issues though more prevalent in Delhi, are seen in other Indian cities as well. The Times of India-IMRB Quality of Life survey conducted in 2011 highlights that the cities of Ahmedabad, Pune, Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Chennai and Kolkatta were all rated below average by the people (Times of India). The parameters were Physical & Civic Infrastructure, Commuting Ease, Peace of Mind, Social Infrastructure, Environment, Leisure Facilities, and Social and Cultural Values.

While the Master Plans of Delhi which guide the cities development, illustrate the strategy for accommodating the vast number of migrants into the city, a strategy for providing a decent standard of living through the design of the physical environment is missing. This case study is based in the urban extension area of Rohini Sub-city first proposed in the Master Plan of Delhi 2001 to be built in five phases, mandating conversion of peripheral agricultural land into urban area. Rohini is well connected to rest of the city by both MRTS and bus systems. City level educational institutes and health facilities are also located here

Phases 4 and 5 of the sub-city are yet to be developed. The planning of the sub-city follows a rubber-stamp approach where a standard pre-designed sector-layout has been blindly proposed to cover the entire land area available. The Zonal Development Plan for Rohini too fails to consider the existing areas with the new development proposed with its back to these areas thereby creating a divide and tension between the two. This speculative case study considers the opportunities to rectify this.

Figure 1: Rohini sub-city plan

Visioning a socially-connected design for Rohini

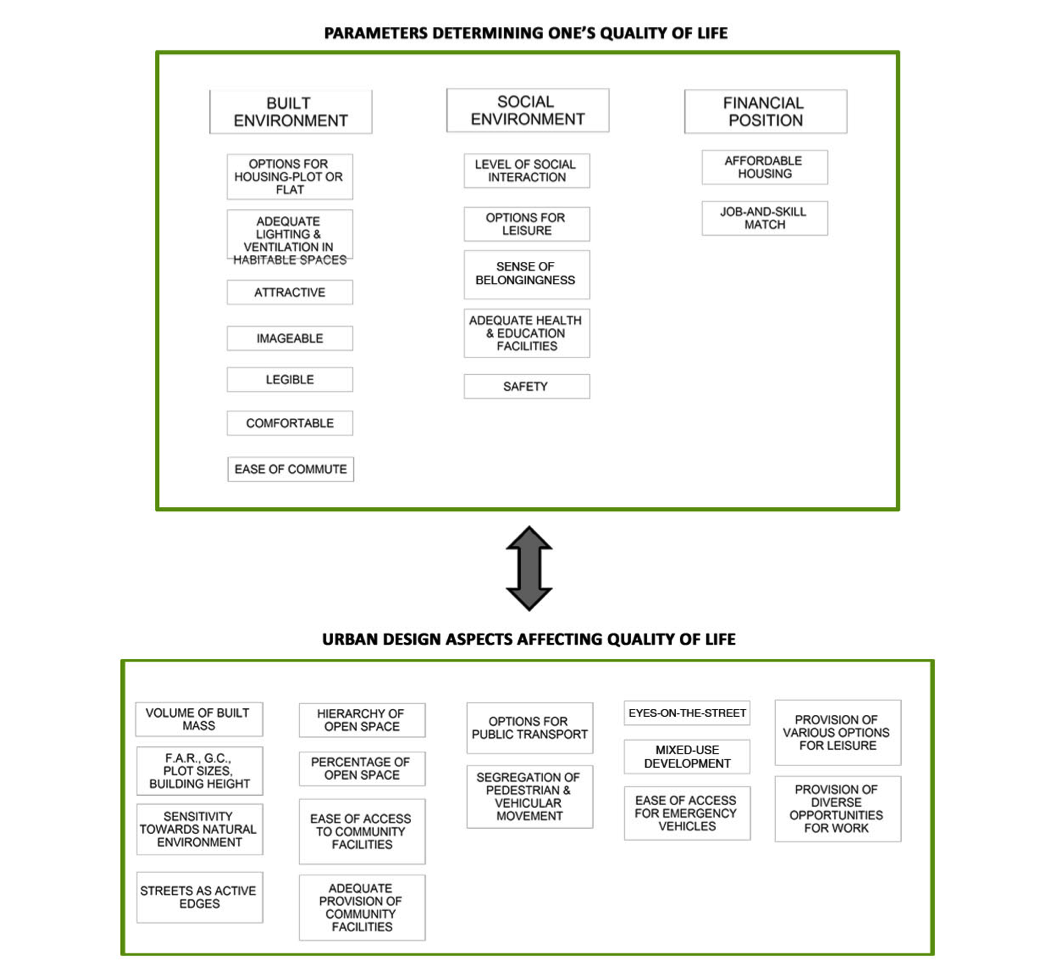

To identify opportunities for design that connects every individual with themselves, each other and with nature, the following quality of life design factors were considered:

Figure 2: urban design aspects affecting quality of life

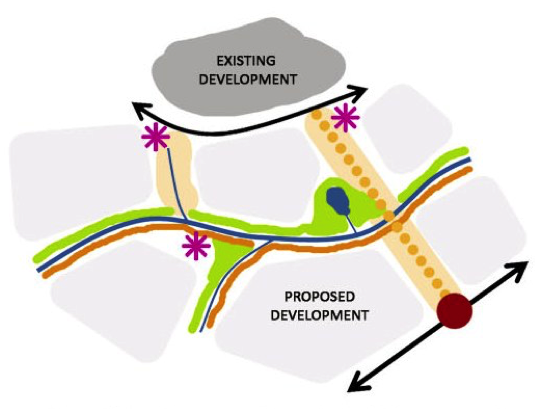

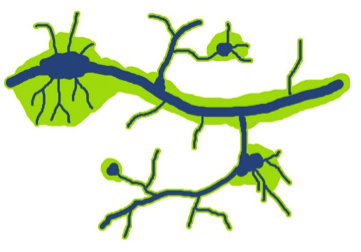

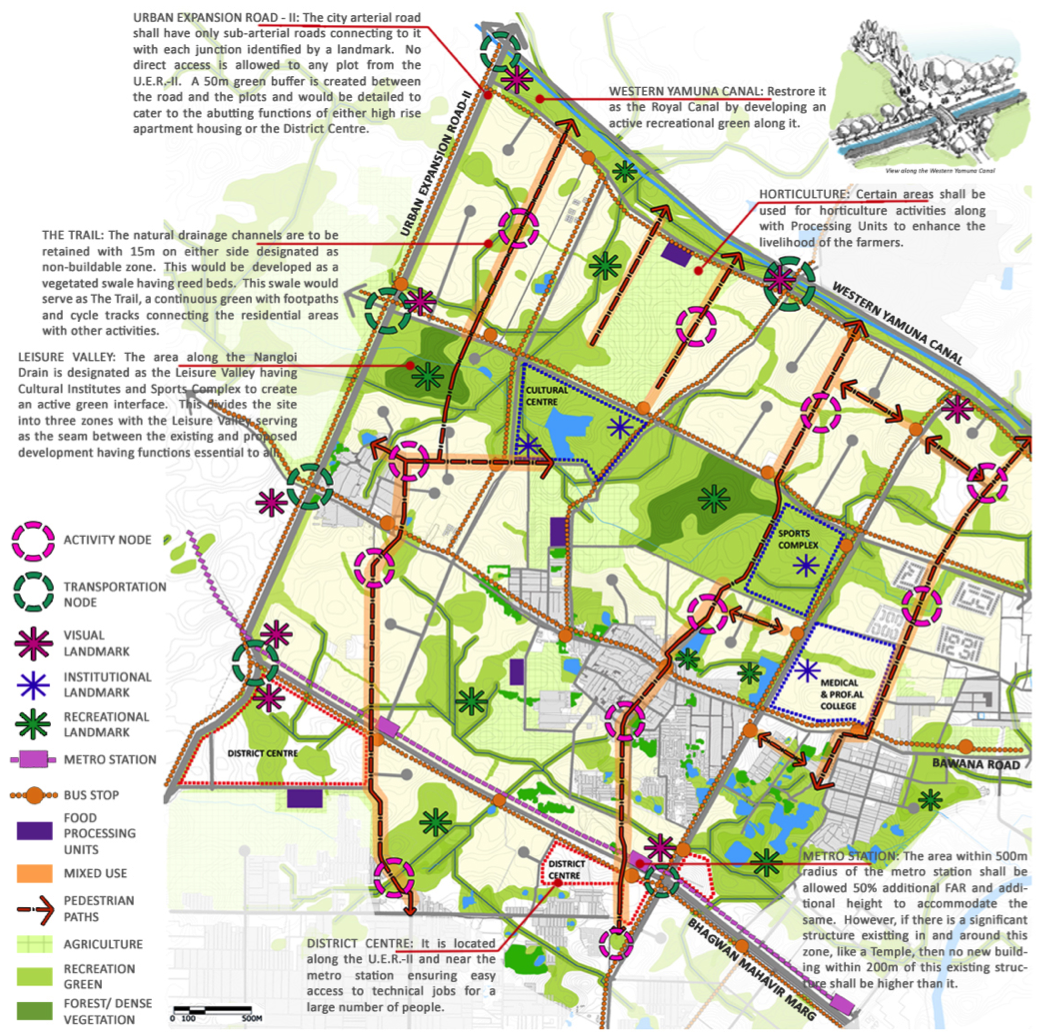

Instead of a standard sector-layout, the terrain of the site could be the starting point. While the land is primarily flat, the natural water drainage channels and subtle variation in contours are important determinants shaping the design. Low-lying areas are unbuilt with some pond-like features, retained as ‘non-buildable’ green spaces alongside new ones. This allows for recharging of aquafers, prevents clogging of drains thereby addressing issues of water shortage and the proliferation of diseases like dengue.

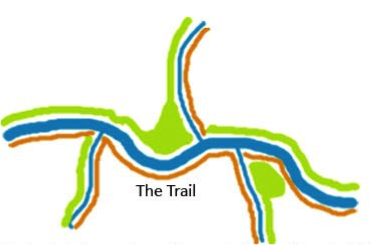

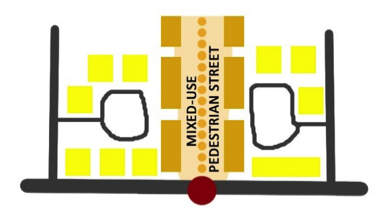

Following traditional wisdom, the natural drainage channels along with 15m buffer on both sides have also been defined as a ‘non-buildable zone’ and either developed as vehicular roads, mixed-use pedestrian streets (MPS), or as a trail i.e. a swale with reed beds.

Following traditional wisdom, the natural drainage channels along with 15m buffer on both sides have also been defined as a ‘non-buildable zone’ and either developed as vehicular roads, mixed-use pedestrian streets (MPS), or as a trail i.e. a swale with reed beds.

Figure 3: non-buildable green space

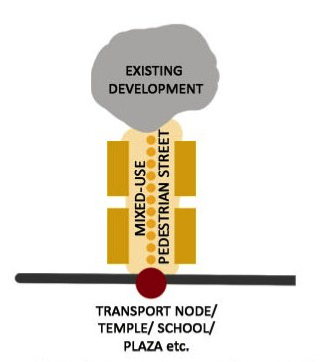

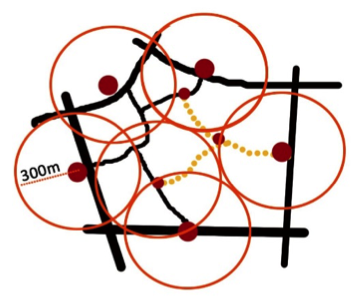

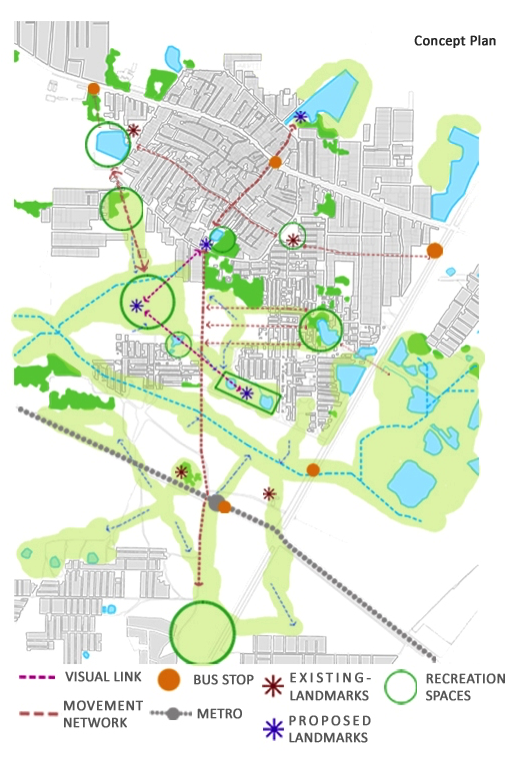

Applying the logic of water to follow the shortest path, MPS could run along the water channels along with new transport nodes, ensuring that every dwelling unit has at least one node within a 300m radius. The standard followed is 500m radius but this results in a greater actual walking distance. A 300m radius ensures a maximum of 500m walking distance which caters to the elderly, pregnant women, and others with limited mobility.

Examining the existing public space nodes and landmarks (existing temples/ponds/parks etc.) and their connections to existing transport nodes (metro station/bus stops/para-transit stands) creates a web of public places and public transport nodes interconnected by either by mixed-use pedestrian street or the Trail. The intent being to facilitate ‘on the way’ linking of everyday needs and recreational activities while facilitating a easy-&-safe walking/cycling experience. This also helps reduce dependency on private vehicles thereby cutting down on traffic and air pollution.

Examining the existing public space nodes and landmarks (existing temples/ponds/parks etc.) and their connections to existing transport nodes (metro station/bus stops/para-transit stands) creates a web of public places and public transport nodes interconnected by either by mixed-use pedestrian street or the Trail. The intent being to facilitate ‘on the way’ linking of everyday needs and recreational activities while facilitating a easy-&-safe walking/cycling experience. This also helps reduce dependency on private vehicles thereby cutting down on traffic and air pollution.

Figure 6 Imagine buying groceries en-route from metro station to home and walking through a park, pausing to sit by the small pond and breathing… if only for a few minutes… existing… with nature… with oneself…

Responding to the natural contours naturally results in green open spaces of varying scales meeting the needs of different age groups, and socio-cultural activities facilitating increased social interaction as well as personal growth.

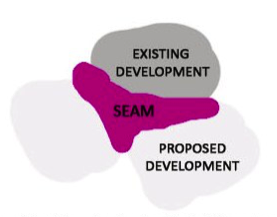

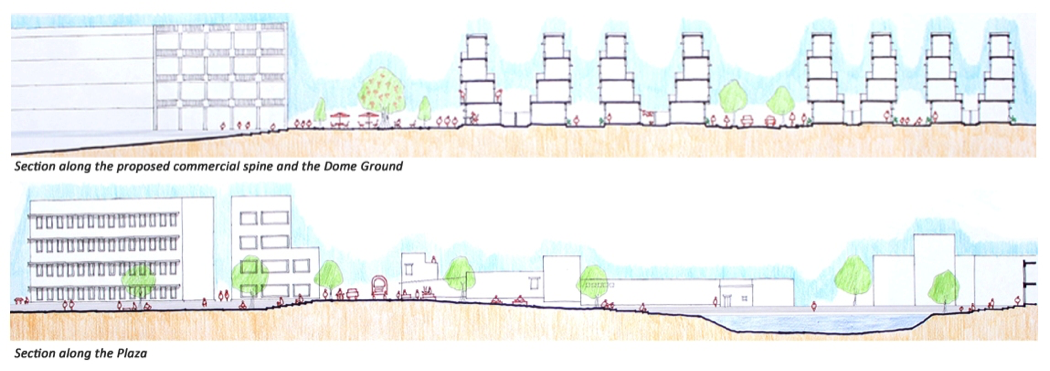

Figure 7. Natural contours

Each of the open spaces could be designed to have a unique identity so as to serve as a landmark for the area. For example, the large open space has a yoga centre where the dome structure serves as a landmark for both the existing and new developments to orient. Public amenities (community centres, health centres, post offices, schools, police station etc) and private places could be placed to create a seam and interface for the existing and proposed developments. These public spaces could provide the setting for social activities, political debates and discussions and deliver equal access to resources and opportunities for congregation through design.

Some major inner roads could be widened to allow for the movement of emergency vehicles; peripheral roads along the settlements for movement of buses. Pedestrian and vehicular movement would be segregated.

To provide work to people previously engaged in agriculture and supporting activities, some of the cultivable land along the existing areas could be retained for Horticulture uses and Food Processing Units. These work centres would be well-integrated into the web.

The mixed-use pedestrian streets could be abutted by commercial activities and hawking zones on the ground level. The upper floors would be residential areas. A mix of plotted row housing and apartment housing would help meet varying preferences and affordability range, . The plot areas could be designed to meet different family sizes and income groups. A staggered built typology could be mandated to ensure terraces at each floor level. The existing areas being dense low-rise settlements, the proposed built form gradually transitions from low-rise high density to high-rise apartment towers. This helps integrate apartment living in gated societies having mixed-use pedestrian edges along with row housing thus offering more options to people.

Some major inner roads could be widened to allow for the movement of emergency vehicles; peripheral roads along the settlements for movement of buses. Pedestrian and vehicular movement would be segregated.

To provide work to people previously engaged in agriculture and supporting activities, some of the cultivable land along the existing areas could be retained for Horticulture uses and Food Processing Units. These work centres would be well-integrated into the web.

The mixed-use pedestrian streets could be abutted by commercial activities and hawking zones on the ground level. The upper floors would be residential areas. A mix of plotted row housing and apartment housing would help meet varying preferences and affordability range, . The plot areas could be designed to meet different family sizes and income groups. A staggered built typology could be mandated to ensure terraces at each floor level. The existing areas being dense low-rise settlements, the proposed built form gradually transitions from low-rise high density to high-rise apartment towers. This helps integrate apartment living in gated societies having mixed-use pedestrian edges along with row housing thus offering more options to people.

Figure 8: Envisioning a new plan for Rohini

At the area level, the same principles could be applied but to cater to a larger population. Hence, the low-lying areas along the major drainage channel becomes the Leisure Valley with different types of functions. Along the metro station, a District Centre is proposed which provides commercial, recreational and office space for technical jobs.

This proposed development at the neighbourhood level facilitates good quality of life. It allows for the new development to be well connected with the existing one creating a seam using shared amenities. Not only do people live in harmony with each other but also enjoy a strong connect with the natural environment. The proposed development is sensitive towards people's daily activities while taking into account their long-term aspirations and wellbeing. A neighbourhood which not only provides its residents with basic facilities but also goes beyond by allowing them to walk freely; to enjoy a connection with nature-sky, sun, moon, fauna and trees, earth and water; to disconnect from the chaos of city-life and personal tensions, to breathe fresh air, and to spend time with their community as well as when desired to spend time only with themselves. The development thus ensures overall growth and development of every individual.

This proposed development at the neighbourhood level facilitates good quality of life. It allows for the new development to be well connected with the existing one creating a seam using shared amenities. Not only do people live in harmony with each other but also enjoy a strong connect with the natural environment. The proposed development is sensitive towards people's daily activities while taking into account their long-term aspirations and wellbeing. A neighbourhood which not only provides its residents with basic facilities but also goes beyond by allowing them to walk freely; to enjoy a connection with nature-sky, sun, moon, fauna and trees, earth and water; to disconnect from the chaos of city-life and personal tensions, to breathe fresh air, and to spend time with their community as well as when desired to spend time only with themselves. The development thus ensures overall growth and development of every individual.

Lessons

In today’s rapidly urbanizing world, Indian cities continue to expand in order to accommodate more and more people. People come from rural areas searching for better work opportunities hoping to upgrade their living conditions. People everywhere aspire for a better quality of life: better education facilities for their kids, better health facilities for the entire family, greater and diverse opportunities for work, parks and fields for various activities, greater opportunities for overall growth and personality development, a strong cultural base, safety and security, healthy and clean living environment, friendly relations at work and in the neighbourhood, and most importantly happiness and peace of mind. By the application of simple universal principles, one can achieve a development which while being rooted specifically in that place, is sensitive towards the needs and aspirations of all its inhabitants, and thus ensure peace.

References

Downs, Anthony; Neighbourhoods and Urban Development; The Brookings Institution; 1981.

Times of India (2011) https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/times-survey-quality-of-life/eventcoverage/11067712.cms

Times of India (2011) https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/times-survey-quality-of-life/eventcoverage/11067712.cms

About the Author

|

Kriti Agarwal is an Architect-Urban Designer with 8 years of diverse professional experience ranging from interiors to architecture to urban design to women's safety. A common feature across all her work has been about exploring the connection between design and human behaviour and psychology. She is currently engaged in research on urban design and mental health alongside her work at an architectural firm. She is also a Visiting Faculty member at Jamia Milia Islamia University's Masters in Ekistics program. She is based in Delhi, India.

|