|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2018:5;5

|

Mental Health by Design: Fostering student emotional wellness in New York City high schools by improving and enhancing built environments

Kelli Peterman, Theadora Swenson, MPH, Takeesha White, MSW, Yianice Hernandez, MNA, Jaimie Shaff, MPA, MPH, Monica Ortiz-Rossi, MFA, MPH, Nivea Jackson, MS

The NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

The NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

Introduction

Recognizing the impact that physical built environments can have on healthy social-emotional development during adolescence, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) launched Mental Health by Design (MHxD) in December 2016, an innovative pilot project that awarded services to 15 New York City (NYC) public high schools to support built environment projects with defined goals of promoting or improving student mental health. The initiative was funded through ThriveNYC, New York City’s comprehensive roadmap to promote the mental health of all New Yorkers,[1]. It was adapted from the DOHMH Active Design in Schools (ADS) program, which promotes healthy physical environments in NYC Department of Education (DOE) public schools through design enhancements, training and technical assistance.[2] Active design is an evidence-based approach to the development and design of buildings, streets and neighborhoods that uses architecture, urban planning and design to improve health and wellbeing.[3]

Social factors, such as socioeconomic status, neighborhood context, and the built environment influence a person’s experiences and lead to disparities in long-term development and health outcomes.[4],[5] Generations of structural racism have led to numerous health inequities related to social factors, including the built environment of school facilities.[6],[7] High school students experience unique stressors related to adolescent development, college preparations, and other systemic and interpersonal factors, and are particularly impacted by the built environment of schools as young people spend much of their time in school.[8],[9]

2015 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data found that 29.4% of NYC public high schoolers reported feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for two or more weeks, as compared to 29.9% nationwide, and 8.3% of NYC public high school students reported having attempted suicide one or more times in the past 12 months, as compared to 8.6% nationwide.[10],[11] In the school year 2013-2014, NYC had a substantially higher proportion of public school students eligible for free or reduced-priced lunch (79.9%) as compared to state (50.2%) and national (52%) levels, indicating high levels of economic insecurity among NYC public school students.[12],[13] Assessments of school facilities report that public schools with a high percentage of students qualifying for free or reduced-priced lunch have lower quality facilities, or physical infrastructures.[14]

Acknowledging these disparities in the quality of school physical environments as well as the mental health needs of NYC students, MHxD focuses on promoting healthy physical spaces as a necessary step towards tackling adolescent mental health inequities within a public health framework.

Social factors, such as socioeconomic status, neighborhood context, and the built environment influence a person’s experiences and lead to disparities in long-term development and health outcomes.[4],[5] Generations of structural racism have led to numerous health inequities related to social factors, including the built environment of school facilities.[6],[7] High school students experience unique stressors related to adolescent development, college preparations, and other systemic and interpersonal factors, and are particularly impacted by the built environment of schools as young people spend much of their time in school.[8],[9]

2015 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data found that 29.4% of NYC public high schoolers reported feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for two or more weeks, as compared to 29.9% nationwide, and 8.3% of NYC public high school students reported having attempted suicide one or more times in the past 12 months, as compared to 8.6% nationwide.[10],[11] In the school year 2013-2014, NYC had a substantially higher proportion of public school students eligible for free or reduced-priced lunch (79.9%) as compared to state (50.2%) and national (52%) levels, indicating high levels of economic insecurity among NYC public school students.[12],[13] Assessments of school facilities report that public schools with a high percentage of students qualifying for free or reduced-priced lunch have lower quality facilities, or physical infrastructures.[14]

Acknowledging these disparities in the quality of school physical environments as well as the mental health needs of NYC students, MHxD focuses on promoting healthy physical spaces as a necessary step towards tackling adolescent mental health inequities within a public health framework.

Methods

The goals of the MHxD pilot were to:

MHxD Ethos

A deliberate focus on health equity and student engagement was built upfront into MHxD, framing the entire scope of the initiative, emphasizing youth voice, shared decision-making, and inclusion of the wider school community in planning and implementation.

Application and Selection

Using the Active Design in Schools (ADS) program application as a model, DOHMH developed a competitive application, criteria, and instructions for schools to apply for the MHxD award. After implementing a targeted outreach strategy, DOHMH received applications from 60 NYC public high schools. The MHxD selection committee selected 15 schools that proposed built environment projects with student input that demonstrated links to improved mental health outcomes (i.e., projects that promote student wellness, facilitate mindfulness, increase students’ connections to one another, improve access to and use of creative spaces, and encourage help-seeking behavior). Importantly, each applicant also needed to outline the type of programming they would conduct in their new spaces, how the programming specifically promoted mental health, and how they would sustain the program. DOHMH prioritized applications from schools that illustrated high need* (an average of 84% of students at MHxD schools were classified by the DOE to be living in poverty[15] and two schools exclusively served students with special needs), dedication to empowering students and improving health equity, and the capacity to implement and maintain the project. Fundamental to the project was the necessity for each school to consider the mental health challenges their students were facing, how their school was currently addressing those challenges, and how the MHxD award could enhance these efforts in a creative, place-based, destigmatizing, and youth-guided way.

- Support school communities in creating or enhancing physical spaces in NYC public high schools that promote emotional wellness and health equity;

- Empower students to be collaborators in reimagining their school spaces and promoting mental health among their peers;

- Assess the feasibility of implementing a multi-dimensional, mental health-focused, school-based active design strategy as a universal intervention within a public health framework.

MHxD Ethos

A deliberate focus on health equity and student engagement was built upfront into MHxD, framing the entire scope of the initiative, emphasizing youth voice, shared decision-making, and inclusion of the wider school community in planning and implementation.

Application and Selection

Using the Active Design in Schools (ADS) program application as a model, DOHMH developed a competitive application, criteria, and instructions for schools to apply for the MHxD award. After implementing a targeted outreach strategy, DOHMH received applications from 60 NYC public high schools. The MHxD selection committee selected 15 schools that proposed built environment projects with student input that demonstrated links to improved mental health outcomes (i.e., projects that promote student wellness, facilitate mindfulness, increase students’ connections to one another, improve access to and use of creative spaces, and encourage help-seeking behavior). Importantly, each applicant also needed to outline the type of programming they would conduct in their new spaces, how the programming specifically promoted mental health, and how they would sustain the program. DOHMH prioritized applications from schools that illustrated high need* (an average of 84% of students at MHxD schools were classified by the DOE to be living in poverty[15] and two schools exclusively served students with special needs), dedication to empowering students and improving health equity, and the capacity to implement and maintain the project. Fundamental to the project was the necessity for each school to consider the mental health challenges their students were facing, how their school was currently addressing those challenges, and how the MHxD award could enhance these efforts in a creative, place-based, destigmatizing, and youth-guided way.

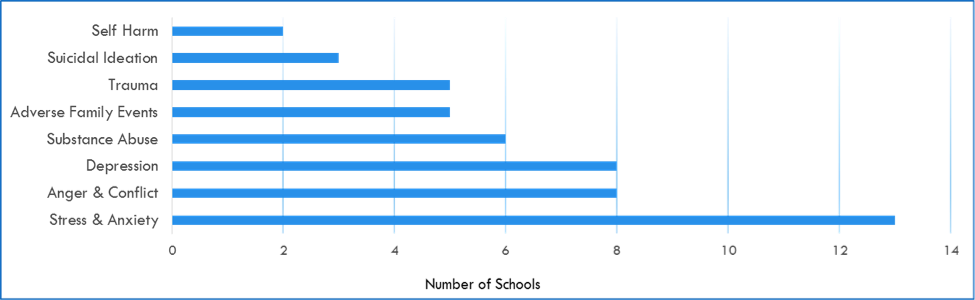

Figure 1: Greatest mental health challenges experienced by students; school-identified (n=15)

Data self-reported by MHxD applicant winners in response to The Fund for Public Health solicitation, December 2016

Award Components:

The MHxD award consisted of three supports[16] for each school: funding to support some or all of the structural project or enhancement itself (i.e., the built environment project); one Architectural Consultant to guide project refinement, vendor selection, and implementation; and the opportunity to send two students to the MHxD Student Development Lab (SDL), a three-session interactive mental health communications workshop developed and led by Hyperakt,[17] a social impact design agency, that facilitated the creation of a personalized, student-led communications strategy to message and market the school’s new space and promote mental health. Each MHxD component was framed by the initiative’s overall ethos: health equity and student engagement. Each awardee needed to clearly demonstrate how students were engaged in the project ideation process, and the MHxD award required that students remained meaningfully involved from planning to implementation. DOHMH’s Youth Advisor, situated within the Bureau of Children, Youth, and Families, played a critical role in ensuring ongoing student engagement by attending planning sessions between schools and their assigned Architectural Consultants and remaining available for ongoing technical assistance in this area.

MHxD Student Development Lab (SDL):

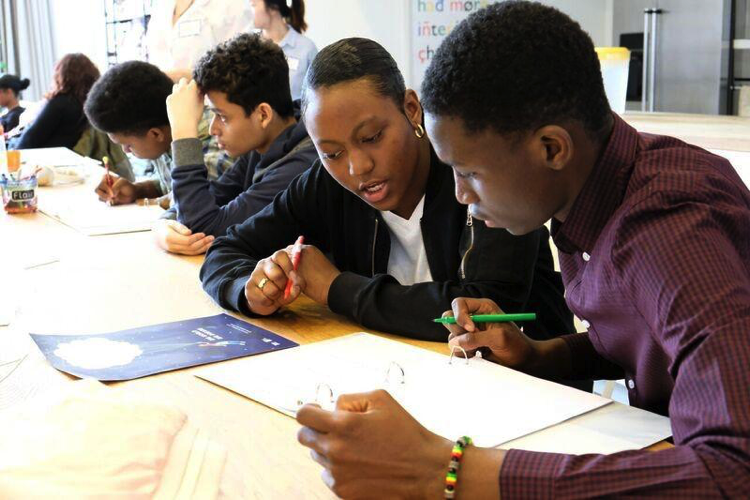

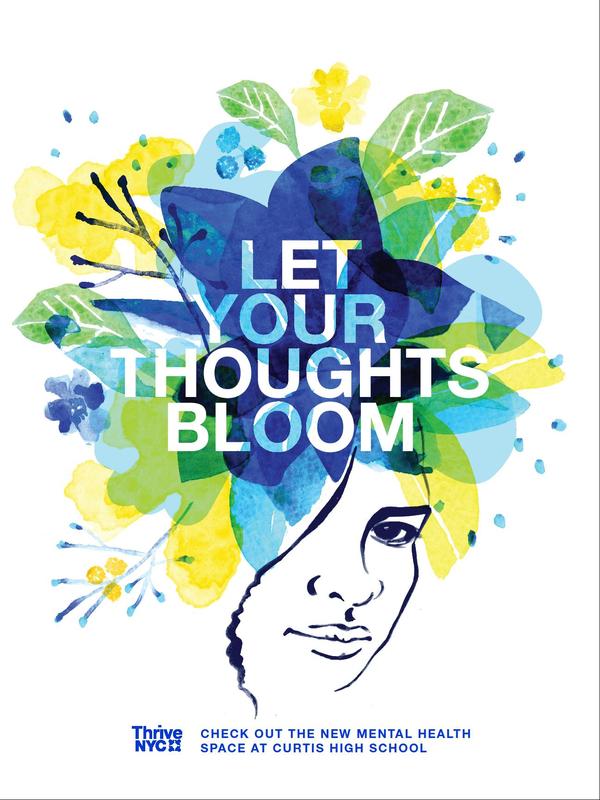

The mission of the MHxD SDL, as described to students in the SDL curriculum, was to provide “a three-week interactive and collaborative engagement that will teach select NYC high school students about the fundamentals of storytelling, design and communications for social impact. Through this program, students will gain the problem-solving, communication and creative skills to advocate for mental health in their communities.” Two students from each school (30 total) were selected by their school administrators to participate in the MHxD SDL, attending three 2-hour sessions over the course of six weeks. Each session was co-designed by Hyperakt and the DOHMH to be fun, interactive and hands-on with student-centered facilitation. During session 1, students defined mental health challenges impacting their peers at their individual schools, brainstormed ideas for improving student mental health in relation to their new MHxD built environment spaces, crafted unique mental health promoting taglines, and developed moodboards.[3] In session two, students were taught how to give constructive critiques and were then presented with individualized poster concepts for each school, designed by the Hyperakt design team, based on the students’ ideas and taglines from session 1. Guided by the students’ critiques, the Hyperakt design teams edited the draft concepts to integrate their recommendations, resulting in final posters for each school, which were printed and presented to each student pair during the third and final session. At this last session, students also developed promotional campaign plans to bring back to their schools to help advertise their new MHxD built environment spaces and the programs occurring within them. In addition to this unique opportunity to work alongside a renowned design firm as “clients” with decision-making power, each student received a stipend for their participation, meals at each session, and transportation to and from the lab. Schools were encouraged to thoughtfully select which students to send to the MHxD SDL as the lab allowed students who might otherwise not be exposed to the design field to consider new future job possibilities for themselves.

The MHxD award consisted of three supports[16] for each school: funding to support some or all of the structural project or enhancement itself (i.e., the built environment project); one Architectural Consultant to guide project refinement, vendor selection, and implementation; and the opportunity to send two students to the MHxD Student Development Lab (SDL), a three-session interactive mental health communications workshop developed and led by Hyperakt,[17] a social impact design agency, that facilitated the creation of a personalized, student-led communications strategy to message and market the school’s new space and promote mental health. Each MHxD component was framed by the initiative’s overall ethos: health equity and student engagement. Each awardee needed to clearly demonstrate how students were engaged in the project ideation process, and the MHxD award required that students remained meaningfully involved from planning to implementation. DOHMH’s Youth Advisor, situated within the Bureau of Children, Youth, and Families, played a critical role in ensuring ongoing student engagement by attending planning sessions between schools and their assigned Architectural Consultants and remaining available for ongoing technical assistance in this area.

MHxD Student Development Lab (SDL):

The mission of the MHxD SDL, as described to students in the SDL curriculum, was to provide “a three-week interactive and collaborative engagement that will teach select NYC high school students about the fundamentals of storytelling, design and communications for social impact. Through this program, students will gain the problem-solving, communication and creative skills to advocate for mental health in their communities.” Two students from each school (30 total) were selected by their school administrators to participate in the MHxD SDL, attending three 2-hour sessions over the course of six weeks. Each session was co-designed by Hyperakt and the DOHMH to be fun, interactive and hands-on with student-centered facilitation. During session 1, students defined mental health challenges impacting their peers at their individual schools, brainstormed ideas for improving student mental health in relation to their new MHxD built environment spaces, crafted unique mental health promoting taglines, and developed moodboards.[3] In session two, students were taught how to give constructive critiques and were then presented with individualized poster concepts for each school, designed by the Hyperakt design team, based on the students’ ideas and taglines from session 1. Guided by the students’ critiques, the Hyperakt design teams edited the draft concepts to integrate their recommendations, resulting in final posters for each school, which were printed and presented to each student pair during the third and final session. At this last session, students also developed promotional campaign plans to bring back to their schools to help advertise their new MHxD built environment spaces and the programs occurring within them. In addition to this unique opportunity to work alongside a renowned design firm as “clients” with decision-making power, each student received a stipend for their participation, meals at each session, and transportation to and from the lab. Schools were encouraged to thoughtfully select which students to send to the MHxD SDL as the lab allowed students who might otherwise not be exposed to the design field to consider new future job possibilities for themselves.

Results

Over a six month period in school year 2016-2017, built environment

projects were almost entirely completed in 15 schools across all 5

boroughs of NYC, accessible to over 10,000 enrolled students, faculty,

and community members. Projects included six exterior spaces (three

gardens, an outdoor classroom, an outdoor mural, and a green space) and

nine interior spaces (three mindfulness/meditation centers, an audio

booth, a student artwork display, a mural, a student lounge, a

restorative/retreat room, and a lobby redesign) with specialized

programming to help students pursue wellness-promoting activities such

as mindfulness, physical activity and self-expression.

Additionally, 30 students were successfully trained in the fundamentals of storytelling, design and communications for social impact and created posters and outreach strategies to increase mental health awareness and community inclusion and promote each school’s new MHxD space. Student pairs also returned to their schools with one professionally printed poster as well as a digital version, and schools later received tote bags branded with their unique poster designs to distribute to students as a further means of promotion.

MHxD SDL participant feedback

“The workers at Hyperakt were great people to work with; if I was struggling when trying to form an idea, they helped get my ideas flowing. They also made sure people participated and were engaged. One of their main focuses seemed to be making sure that everyone left with more information than what they came in with and to help us get the tools to tell a captivating story with our mental spaces/garden. The workers were also very talented people; after seeing the posters, I was intrigued at how they expressed the mood boards and the ideas in the poster.”

“I absolutely loved working with Hyperakt. It was a super cool office space and an awesome environment to work in. I also loved working with my partner and all the other students who were there. I loved working on health issues with other schools. It opened my eyes up to what other schools are struggling with.”

“Surrounding ourselves with new people was fun and made me more open to meeting new people. The Hyperakt team broke down the steps and made it relatable to our daily life. As a creative person I enjoyed creating a mood board and tagline.”

“[The MHxD SDL] was an enjoyable experience for me. While providing criticism for the poster design allowed me to have a voice and to express what I liked and what parts could be fixed about the posters, the incentives were also another push to do better. Whether it be participating more or making our mood board more detailed; it was like I was earning the incentives.”

Additionally, 30 students were successfully trained in the fundamentals of storytelling, design and communications for social impact and created posters and outreach strategies to increase mental health awareness and community inclusion and promote each school’s new MHxD space. Student pairs also returned to their schools with one professionally printed poster as well as a digital version, and schools later received tote bags branded with their unique poster designs to distribute to students as a further means of promotion.

MHxD SDL participant feedback

“The workers at Hyperakt were great people to work with; if I was struggling when trying to form an idea, they helped get my ideas flowing. They also made sure people participated and were engaged. One of their main focuses seemed to be making sure that everyone left with more information than what they came in with and to help us get the tools to tell a captivating story with our mental spaces/garden. The workers were also very talented people; after seeing the posters, I was intrigued at how they expressed the mood boards and the ideas in the poster.”

“I absolutely loved working with Hyperakt. It was a super cool office space and an awesome environment to work in. I also loved working with my partner and all the other students who were there. I loved working on health issues with other schools. It opened my eyes up to what other schools are struggling with.”

“Surrounding ourselves with new people was fun and made me more open to meeting new people. The Hyperakt team broke down the steps and made it relatable to our daily life. As a creative person I enjoyed creating a mood board and tagline.”

“[The MHxD SDL] was an enjoyable experience for me. While providing criticism for the poster design allowed me to have a voice and to express what I liked and what parts could be fixed about the posters, the incentives were also another push to do better. Whether it be participating more or making our mood board more detailed; it was like I was earning the incentives.”

Figure 3:

MHxD SDL

posters - courtesy of Hyperakt

MHxD faculty leads feedback

Preliminary anecdotal feedback from faculty leads (“MHxD Project Leads”) supporting MHxD implementation at each school, collected via follow-up visits, emails, and phone calls, suggest that student driven improvements to the physical environment of schools can have a positive impact on student and faculty emotional wellness.

“[MHxD] has enabled us to provide a calming atmosphere for our Restorative Circles. We have used the space for every orientation so that we can set the tone for our Restorative Practice culture. Every student experiences a circle on their first visit to the school. The space has even changed the tone in classrooms. Teachers have signed up to use the space for discussions!”

“I received a voice mail from a staff member that was having a rough morning and went outside for a break.After walking through the garden and sitting for a few minutes he informed me that his mood brightened and was able to return to his job with a clearer mind.”

Preliminary anecdotal feedback from faculty leads (“MHxD Project Leads”) supporting MHxD implementation at each school, collected via follow-up visits, emails, and phone calls, suggest that student driven improvements to the physical environment of schools can have a positive impact on student and faculty emotional wellness.

“[MHxD] has enabled us to provide a calming atmosphere for our Restorative Circles. We have used the space for every orientation so that we can set the tone for our Restorative Practice culture. Every student experiences a circle on their first visit to the school. The space has even changed the tone in classrooms. Teachers have signed up to use the space for discussions!”

“I received a voice mail from a staff member that was having a rough morning and went outside for a break.After walking through the garden and sitting for a few minutes he informed me that his mood brightened and was able to return to his job with a clearer mind.”

Project Spotlight: Brooklyn College Academy

As an Early College High School,[19] Brooklyn College Academy (BCA) students are exposed to a rigorous academic environment that can be as rewarding as it is challenging. BCA was classified as a low-income school for the 2015-2016 school year by the U.S. Department of Education,[20] and many of the nearly 600 BCA students face stressors related to family, housing, mental health, and immigration. Although mindfulness practices had been incorporated into some classrooms and staff meetings prior to receiving the MHxD award, BCA wanted a mindfulness center that would be situated away from students’ regular classes to give them a place to reflect and reset. The BCA MHxD Project Lead also envisioned the mindfulness center as a lab for expanded research, implementation, and sustainability of mindfulness and related practices at the school. Through the MHxD award, and strategic partnerships with design vendor, Homepolish[21] and MDFL Ed,[22] a nonprofit community based organization that aims to make meditation accessible to NYC children and youth in under-resources school communities, BCA converted a storage room into a beautifully designed mindfulness center. MDFL Ed co-developed, implemented, and is evaluating a meditation curriculum for BCA students and teachers. Learn more about the BCA Mindfulness Center here.

As an Early College High School,[19] Brooklyn College Academy (BCA) students are exposed to a rigorous academic environment that can be as rewarding as it is challenging. BCA was classified as a low-income school for the 2015-2016 school year by the U.S. Department of Education,[20] and many of the nearly 600 BCA students face stressors related to family, housing, mental health, and immigration. Although mindfulness practices had been incorporated into some classrooms and staff meetings prior to receiving the MHxD award, BCA wanted a mindfulness center that would be situated away from students’ regular classes to give them a place to reflect and reset. The BCA MHxD Project Lead also envisioned the mindfulness center as a lab for expanded research, implementation, and sustainability of mindfulness and related practices at the school. Through the MHxD award, and strategic partnerships with design vendor, Homepolish[21] and MDFL Ed,[22] a nonprofit community based organization that aims to make meditation accessible to NYC children and youth in under-resources school communities, BCA converted a storage room into a beautifully designed mindfulness center. MDFL Ed co-developed, implemented, and is evaluating a meditation curriculum for BCA students and teachers. Learn more about the BCA Mindfulness Center here.

Brooklyn College Academy: before and after

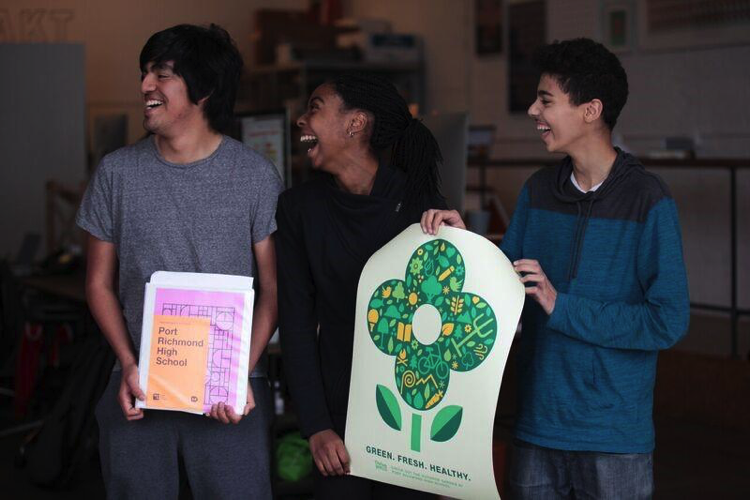

Brooklyn

College Academy – MHxD SDL participants and poster

Conclusions and Recommendations

Using a public mental health framework informed by ThriveNYC and the Active Design in Schools program, with a particular focus on community partnerships, DOHMH successfully piloted an active design intervention that promoted mental health, youth engagement, and health equity. The following are five key conclusions and recommendations:

1. With appropriate resources and time, it is feasible to implement active design strategies aimed at increasing mental health awareness and opportunities for improving student mental health within high schools. Securing additional funding to maintain the spaces on an ongoing basis and sustain the mental health programming is also recommended.

2. Commitment of one strong school staff member to champion the project is essential for

implementation; involvement of multiple school-based stakeholders can support long-term sustainability and minimize champion burnout.

3. Engaging students and youth as partners in guiding active design projects intended for them, while providing leadership and learning opportunities such as the MHxD Student Development Lab, can meaningfully enhance the project’s scope and facilitate authentic youth participation.

4. A comprehensive understanding of school-specific procedures, local building regulations, and legal considerations is essential at concept stage and should be revisited throughout the implementation process. Additionally, a full school year is recommended for implementation to account for unforeseen obstacles related to such regulations and to alleviate grant pressures on school staff, which were at times complex or unexpected, particularly at the end of the school year.

“We are grateful that we were chosen for this grant and are happy that we now have a meditation room; however, we feel the grant ended up being more work on our end than we would have hoped, especially at such a busy time as the end of the school year.” – MHxD Project Lead

5. The mental health climate of NYC schools vary, supporting the need to apply a place-based, participatory approach to plan and implement projects that engage school communities and address their specific needs; to do so thoughtfully, it is important to apply a health equity lens.

“Inequities in health are unfair, unnecessary and avoidable. New York City is one of the most unequal cities in the United States and one of the most segregated. It is no surprise that these everyday realities are reflected in our health. A more deliberate effort to name and address these disparities will frame all that we do.” – NYC Health Commissioner Mary T. Bassett, MD, MPH[1]

1. With appropriate resources and time, it is feasible to implement active design strategies aimed at increasing mental health awareness and opportunities for improving student mental health within high schools. Securing additional funding to maintain the spaces on an ongoing basis and sustain the mental health programming is also recommended.

2. Commitment of one strong school staff member to champion the project is essential for

implementation; involvement of multiple school-based stakeholders can support long-term sustainability and minimize champion burnout.

3. Engaging students and youth as partners in guiding active design projects intended for them, while providing leadership and learning opportunities such as the MHxD Student Development Lab, can meaningfully enhance the project’s scope and facilitate authentic youth participation.

4. A comprehensive understanding of school-specific procedures, local building regulations, and legal considerations is essential at concept stage and should be revisited throughout the implementation process. Additionally, a full school year is recommended for implementation to account for unforeseen obstacles related to such regulations and to alleviate grant pressures on school staff, which were at times complex or unexpected, particularly at the end of the school year.

“We are grateful that we were chosen for this grant and are happy that we now have a meditation room; however, we feel the grant ended up being more work on our end than we would have hoped, especially at such a busy time as the end of the school year.” – MHxD Project Lead

5. The mental health climate of NYC schools vary, supporting the need to apply a place-based, participatory approach to plan and implement projects that engage school communities and address their specific needs; to do so thoughtfully, it is important to apply a health equity lens.

“Inequities in health are unfair, unnecessary and avoidable. New York City is one of the most unequal cities in the United States and one of the most segregated. It is no surprise that these everyday realities are reflected in our health. A more deliberate effort to name and address these disparities will frame all that we do.” – NYC Health Commissioner Mary T. Bassett, MD, MPH[1]

Next steps

DOHMH is planning to provide ongoing technical assistance to the current cohort of MHxD schools to support continued utilization of their new spaces as well as advocate for funding to bring MHxD to scale or apply to other environments. Additionally, DOHMH intends to conduct an evaluation of the impact of the built environment changes on student and staff knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding mental health, specifically assessing the differences in outcomes for spaces with and without consistent specialized programming, as well as an evaluation of the MHxD Student Development Lab and the impact of student-driven messaging campaigns to address mental health topics. DOHMH would like to especially thank the staff members at each school for their dedication to their students’ emotional wellness and for their participation in this pilot, without whom the MHxD initiative would have been impossible.

Acknowledgments:

- Brooklyn College Academy: Nicholas Mazzarella, Principal; David Genovese, Assistant Principal; Linda Noble, MHxD Project Lead

- Hyperakt

- Karen Kubey, Architectural Consultant

- Mark K. Morrison, Architectural Consultant

- Reyes Melendez

- The Fund for Public Health NYC

- The NYC Department of Education

References

[1] Mental Health Roadmap. Thrive NYC Website. https://thrivenyc.cityofnewyork.us/. Accessed November 1, 2016

[2] Active Design Toolkit for Schools. Center for Active Design Website. https://centerforactivedesign.org/activedesigntoolkitforschools. Accessed November 1, 2016

[3] Active Design Guidelines: Promoting Physical Activity and Health in Design. New York City Website. http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/environmental/active-design-guidelines.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2016

[4] Alegria M, Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Loder S. 2015. Disparities in child and adolescent mental health and mental health services in the U.S., 2015. New York: William T. Grant Foundation. http://wtgrantfoundation.org/library/uploads/2015/09/Disparities-in-Child-and-Adolescent-Mental-Health.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[5] Evans GW. The built environment and mental health. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4):536-555.

[6] Center for Health Equity. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Website. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/neighborhood-health/center-for-health-equity.page. Accessed November 1, 2016

[7] Bailey, ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463.

[8] Mesiti-Ceas, T. A look at the evidence linking school design to student outcome. CSArch: The Councilgram. 2015; http://www.csarchpc.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Published-Article-NYSCOSS-Councilgram-Feb.-2015.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[9] Cheryan S, Ziegler SA, Plaut VC, et al. Designing classrooms to maximize student achievement. Policy Insights from the Behavior and Brain Science. 2014; 1(1):4-12.

[10] New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Epiquery: NYC Interactive Health Data System - Youth Risk Behavior Survey 2015. [October 24, 2017]. https://nyc.gov/health/epiquery

[11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1991-2017 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/. Accessed on June 20, 2018.

[12] Data About Schools. New York City Department of Education. http://schools.nyc.gov/AboutUs/schools/data/default.htm. Published January 20, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[13]U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data (CCD). Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey 2000-01, 2010-11, 2012-13, and 2013-14.

[14] Falling Further Apart. SEIU 32BJ. http://www.seiu32bj.org/falling-further-apart-decaying-schools-in-new-york-citys-poorest-neighborhoods/. Published May 2013. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[15] Data About Schools. New York City Department of Education. http://schools.nyc.gov/AboutUs/schools/data/default.htm. Published January 20, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017

[16] The MHxD service package amounted to approximately $22,000 per school

[17] For more information, visit the Hyperakt website: http://hyperakt.com/

[18] A moodboard is an arrangement of images, text, materials, etc., that help designers find inspiration and guidance when translating a problem into a design solution – MHxD Student Development Lab Curriculum, page 18

[19] Early College Initiative at CUNY Website. http://earlycollege.cuny.edu/. Accessed June 1, 2018.

[20] Data About Schools. New York City Department of Education. http://schools.nyc.gov/AboutUs/schools/data/default.htm. Published January 20, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[21] For more information, visit the Homepolish website: https://www.homepolish.com/

[22] For more information, visit the MNDFL Ed. Website: https://www.mndflmeditation.com/education

[23] Center for Health Equity. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Website. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/neighborhood-health/center-for-health-equity.page. Accessed June 1, 2018

[2] Active Design Toolkit for Schools. Center for Active Design Website. https://centerforactivedesign.org/activedesigntoolkitforschools. Accessed November 1, 2016

[3] Active Design Guidelines: Promoting Physical Activity and Health in Design. New York City Website. http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/environmental/active-design-guidelines.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2016

[4] Alegria M, Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Loder S. 2015. Disparities in child and adolescent mental health and mental health services in the U.S., 2015. New York: William T. Grant Foundation. http://wtgrantfoundation.org/library/uploads/2015/09/Disparities-in-Child-and-Adolescent-Mental-Health.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[5] Evans GW. The built environment and mental health. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4):536-555.

[6] Center for Health Equity. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Website. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/neighborhood-health/center-for-health-equity.page. Accessed November 1, 2016

[7] Bailey, ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463.

[8] Mesiti-Ceas, T. A look at the evidence linking school design to student outcome. CSArch: The Councilgram. 2015; http://www.csarchpc.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Published-Article-NYSCOSS-Councilgram-Feb.-2015.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[9] Cheryan S, Ziegler SA, Plaut VC, et al. Designing classrooms to maximize student achievement. Policy Insights from the Behavior and Brain Science. 2014; 1(1):4-12.

[10] New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Epiquery: NYC Interactive Health Data System - Youth Risk Behavior Survey 2015. [October 24, 2017]. https://nyc.gov/health/epiquery

[11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1991-2017 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/. Accessed on June 20, 2018.

[12] Data About Schools. New York City Department of Education. http://schools.nyc.gov/AboutUs/schools/data/default.htm. Published January 20, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[13]U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data (CCD). Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey 2000-01, 2010-11, 2012-13, and 2013-14.

[14] Falling Further Apart. SEIU 32BJ. http://www.seiu32bj.org/falling-further-apart-decaying-schools-in-new-york-citys-poorest-neighborhoods/. Published May 2013. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[15] Data About Schools. New York City Department of Education. http://schools.nyc.gov/AboutUs/schools/data/default.htm. Published January 20, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017

[16] The MHxD service package amounted to approximately $22,000 per school

[17] For more information, visit the Hyperakt website: http://hyperakt.com/

[18] A moodboard is an arrangement of images, text, materials, etc., that help designers find inspiration and guidance when translating a problem into a design solution – MHxD Student Development Lab Curriculum, page 18

[19] Early College Initiative at CUNY Website. http://earlycollege.cuny.edu/. Accessed June 1, 2018.

[20] Data About Schools. New York City Department of Education. http://schools.nyc.gov/AboutUs/schools/data/default.htm. Published January 20, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017.

[21] For more information, visit the Homepolish website: https://www.homepolish.com/

[22] For more information, visit the MNDFL Ed. Website: https://www.mndflmeditation.com/education

[23] Center for Health Equity. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Website. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/neighborhood-health/center-for-health-equity.page. Accessed June 1, 2018

About the Authors

|

Kelli Peterman is the Prevention and Community Support Specialist in the Bureau of Children, Youth, and Families at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH). Kelli oversees a diverse portfolio of initiatives related to mental health and adolescents, including Mental Health by Design, youth peer advocacy, and various suicide prevention and ThriveNYC activities. Prior to this role, she served as the Deputy Director of Project HOPE at DOHMH, NYC’s crisis counseling program in response to Hurricane Sandy and as the Senior Crisis Services Manager at The Trevor Project. Kelli looks forward to beginning the City and Regional Planning graduate program at Pratt Institute in August 2018, focusing on the intersection of mental health and the built environment.

|

|

Takeesha White, LMSW, is the Executive Director of Strategic Planning and Communications in the Bureau of Division Management for the Center for Health Equity at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Takeesha manages a multi-disciplinary team of leaders overseeing programming and planning in policy, criminal justice, strategic and experiential communications, community engagement and neighborhood based behavioral health. Formerly, as Senior Director of Networks and Coalitions, in the Division of Mental Hygiene, Takeesha lead local efforts in mental health promotion, community connectivity and digital strategies for Thrive NYC. Takeesha received her Bachelor's in Sociology and Economics at Columbia University, in New York City and Master’s in International Social Work with a focus on Economic Development at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis.

|

|

Teddy

Swenson, MPH, is the Program Manager for the Active Design

Program within the Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention and Tobacco Control at

the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Teddy manages the

Active Design in Schools Program which supports built environment enhancements

that increase access to physical activity and active play opportunities in NYC

public schools. She also oversees and conducts program evaluation and related

research. Teddy received her MPH in Epidemiology from Columbia University

Mailman School of Public Health with a Certificate in the Social Determinants

of Health.

|

|

Nivea Jackson, M.S, is the Youth Advisor in the Bureau of

Children, Youth, and Families at the New York City Department of Health and

Mental Hygiene. Ms. Jackson brings knowledge professionally and personally,

dedication and passion for supporting and advocating for youth and young adults

in multiple child serving systems. As the Youth Advisor, Nivea ensures that the

voice of youth are represented throughout her division Mental Hygiene and

bureau Children, Youth and Families. Nivea received her Master’s in Mental

Health Counseling at Long Island University Brooklyn Campus.

|

|

Jaimie Shaff is an Implementation and Evaluation Specialist for the

Bureau of Children, Youth and Families at the New York City Department of

Health and Mental Hygiene. She holds a Master’s in Public Health (Epidemiology)

from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a Master’s of Public

Administration from New York University’s Wagner School of Public Service.

|

|

Yianice Hernandez, Director of

Capital Planning for the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), oversees the

allocation of federal, state and city capital resources to preserve NYCHA’s

housing stock to provide safe, clean, connected homes for over 400,000 New

Yorkers. Previously, she served as Director of Healthy Living by Design at the

NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, where she led the development and

implementation of citywide initiatives that promote healthy community

development. Prior to working with New York City, she served as Director of

Enterprise Green Communities with Enterprise Community Partners, Inc., where

she directed the execution of strategic programmatic priorities that advanced

green affordable housing nationally. Yianice has a bachelor's degree in

Sociology from Pace University and a master's degree in nonprofit administration

from the University of Notre Dame.

|

|

Monica

Ortiz Rossi is the Physical

Activity Manager in the Office of School Wellness Programs at the NYC

Department of Education. Previously, she served as the Active Design

Coordinator at the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene where she worked

on transforming schools spaces to create opportunities for physical activity

and health. She has worked on injecting movement into urban spaces through

traditional methods (active design strategies, dance/yoga classes, fitness

opportunities and music shows) and non-traditional methods (site-specific

movement pieces in a rotating box in Los Angeles or in the windows of the

Brooklyn Public Library.) She is committed to engineering equity through

movement to protect the health of our population.

|