|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2018:5;7

|

A Case Study of Urban Design and Mental Health in Las Vegas

Dak Kopec, Ph.D., MS.Arch., MCHES.

Associate Professor, School of Architecture, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, USA

Associate Professor, School of Architecture, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, USA

Introduction

The birth of an unusual city

The City of Las Vegas sits at the southernmost point within the state of Nevada surrounded by the Mojave Desert. Founded in 1911, Las Vegas is a little more than 110 years old; relative to other cities in the United States, Las Vegas is still young. Nevada has always assumed a special role in the United States because it allowed for quick divorces, prostitution, and gambling.

Las Vegas experienced significant growth from the late 1920’s into the 1930’s with the construction of Hoover Dam. This enormous project encouraged mass migration of men from all over the country to Las Vegas. Most of these men wanted a chance for a new beginning after the 1929 Stock Market Crash. Las Vegas thus became a town predominantly occupied by working blue-collar men, and the businesses that thrived met the needs of these men. Being a city in virtual isolation, and with a population composed mostly of younger men who worked hard and labored long hours, fomented for an ideal business environment that catered to the vice of men. Behaviors that were a normal part of daily life in Las Vegas such as gambling, alcohol consumption, and prostitution have all been tied to mental health either as a precursor or an outcome.

Hoover Dam was completed in 1936, and the roots of gambling, drinking, and prostitution attracted the attentions of New York Mobster Bugsy Siegel who took over the construction of a hotel-casino on what was then the edge of Las Vegas in 1945. The Mob Museum (n.d.) reports that Siegel’s vision was for a glamorous high-quality resort in the desert. The degree of glamor set by Siegel elevated the expected norms for other similar style resorts. Siegel convinced the bosses of the Eastern Crime Syndicate to finance the Flamingo Hotel at a cost of $6 million. Las Vegas was essentially primed for the mob syndicate to take the city to the next level in its evolution. The addition of organized crime, which promotes pathologies (mental health issues) of violence, retribution, and absolute loyalty among its members, gains much of its profit from behaviors such as gambling, alcohol, and prostitution.

Throughout the 1940’s Las Vegas continued to grow, and the advent of World War Two saw the development of military bases erected on the rural desert lands north of Las Vegas. Again, the city would be filled with young men who would spend much of their available time in the city. The gambling, drinking and prostitution established in the 30’s and built upon by the mafia were strong attractions for young military men. Throughout World War Two and well into the 1950’s, these roots resulted in higher male populations within the city.

The core of Las Vegas’s economic foundation was based on the primal desires of young men. However, these primal desires also forged a basis for mental health concerns. Some of these concerns became exacerbated with the growing interest in vice, and some resulted from the lifestyle that promoted gambling, alcohol consumption, and prostitution.

Modern Las Vegas

Today, Las Vegas has embraced its identity and holds tight to the city’s mantra; one that is widely regarded as the most powerful and successful advertising slogans: “What Happens in Vegas Stays in Vegas” (Hildreth, 2010). The city is unapologetic, and in many respects, proud of its unique place among the many cities that compose the United States. But, according to Sir Isaac Newton, for every action there is a reaction. Whether legal or not, and just as in most of world’s major cities, prostitution, gambling, and alcohol (among other mind-altering substances) are vices easily satisfied in Las Vegas. The reaction is that people with an alcohol use disorder are more likely to be gamblers, and engage in impulsive, compulsive, and depressive types of behaviors (Harries, et. al., 2017). These behaviors may include the trade of sex for cash, and possible suicide.

The City of Las Vegas sits at the southernmost point within the state of Nevada surrounded by the Mojave Desert. Founded in 1911, Las Vegas is a little more than 110 years old; relative to other cities in the United States, Las Vegas is still young. Nevada has always assumed a special role in the United States because it allowed for quick divorces, prostitution, and gambling.

Las Vegas experienced significant growth from the late 1920’s into the 1930’s with the construction of Hoover Dam. This enormous project encouraged mass migration of men from all over the country to Las Vegas. Most of these men wanted a chance for a new beginning after the 1929 Stock Market Crash. Las Vegas thus became a town predominantly occupied by working blue-collar men, and the businesses that thrived met the needs of these men. Being a city in virtual isolation, and with a population composed mostly of younger men who worked hard and labored long hours, fomented for an ideal business environment that catered to the vice of men. Behaviors that were a normal part of daily life in Las Vegas such as gambling, alcohol consumption, and prostitution have all been tied to mental health either as a precursor or an outcome.

Hoover Dam was completed in 1936, and the roots of gambling, drinking, and prostitution attracted the attentions of New York Mobster Bugsy Siegel who took over the construction of a hotel-casino on what was then the edge of Las Vegas in 1945. The Mob Museum (n.d.) reports that Siegel’s vision was for a glamorous high-quality resort in the desert. The degree of glamor set by Siegel elevated the expected norms for other similar style resorts. Siegel convinced the bosses of the Eastern Crime Syndicate to finance the Flamingo Hotel at a cost of $6 million. Las Vegas was essentially primed for the mob syndicate to take the city to the next level in its evolution. The addition of organized crime, which promotes pathologies (mental health issues) of violence, retribution, and absolute loyalty among its members, gains much of its profit from behaviors such as gambling, alcohol, and prostitution.

Throughout the 1940’s Las Vegas continued to grow, and the advent of World War Two saw the development of military bases erected on the rural desert lands north of Las Vegas. Again, the city would be filled with young men who would spend much of their available time in the city. The gambling, drinking and prostitution established in the 30’s and built upon by the mafia were strong attractions for young military men. Throughout World War Two and well into the 1950’s, these roots resulted in higher male populations within the city.

The core of Las Vegas’s economic foundation was based on the primal desires of young men. However, these primal desires also forged a basis for mental health concerns. Some of these concerns became exacerbated with the growing interest in vice, and some resulted from the lifestyle that promoted gambling, alcohol consumption, and prostitution.

Modern Las Vegas

Today, Las Vegas has embraced its identity and holds tight to the city’s mantra; one that is widely regarded as the most powerful and successful advertising slogans: “What Happens in Vegas Stays in Vegas” (Hildreth, 2010). The city is unapologetic, and in many respects, proud of its unique place among the many cities that compose the United States. But, according to Sir Isaac Newton, for every action there is a reaction. Whether legal or not, and just as in most of world’s major cities, prostitution, gambling, and alcohol (among other mind-altering substances) are vices easily satisfied in Las Vegas. The reaction is that people with an alcohol use disorder are more likely to be gamblers, and engage in impulsive, compulsive, and depressive types of behaviors (Harries, et. al., 2017). These behaviors may include the trade of sex for cash, and possible suicide.

Mental Health

The National Alliance on Mental Health’s website (2017) suggests that mental health problems in the United States are increasing. These increases can be attributed to multiple factors that include: better diagnosis, increased awareness by the public, increased numbers of elderly people experiencing cognitive decline, and a rise in homeless populations. Some types of mental health problems such as schizophrenia can be related back to a genetic predisposition (Horvath and Mirnics, 2015) coupled with psychosocial factors. Other mental health conditions have their roots in social discourse (Layous, Chancellor & Lyubomirsky, 2014). Loneliness and isolation are often a precursor for depression (Cacioppo, Hawkley & Thisted, 2010), which can be exacerbated by inadequate provisions of social services.

Within the United States, health service provisions tend to be clustered according to age, gender, ethnicity, and then further clustered according to type of health condition such as psychotic disorders (bipolar disorder and schizophrenia), addiction-based disorders (i.e. alcohol, drug, and sexual activity), and age-related disorders (i.e. changes in cognition, mobility, and sensory detection). Hence, it is not uncommon to find specific social service programs for African American women who are intravenous (I.V.) drug users. This multicluster (ethnic, gender, and condition) approach is an effective method for the allocation and distribution of funds from federal and state agencies, and is effective in the reduction of confounding variables that could invalidate outcome measures. However, this cluster approach presupposes only people that fall within those multicluster parameters require assistance. Provisions for those outside of the clusters are assumed to be without need or low in priority.

Mental health services in the United States tend to be funded through federal and state sponsored grants based on multicluster criteria. This method of grant funding, and the growth of social services that survive from these funds, often leaves gaping holes in the available services. For example, services for drug and alcohol-based addictions may or may not concurrently address other behavior-based addictions, such as sexual or gambling addiction. Drug and alcohol addictions are intertwined with sexual (Sussman, 2017) and other forms of addictions, but that portion of the problem may not be addressed because it exceeds the scope of the grant/funding source.

Mental Health and The Environment

The Biopsychosocial Model is based on the idea that an interaction between biological factors such as genetics and the biochemical alteration at the cellular level, combined with psychological factors related to personality and disposition, and social factors linked to socioeconomics and environment combine to bring about illness or disorder (Engel, 1977). This model supports the idea that designers of the built environment can serve as collaborators in the prevention, rehabilitation, and accommodation of psychobiological illnesses and physical disorders.

Stress and dehydration are examples of psychological and biological predictors of impaired cognition. Wilson and Morley (2003) have shown that severe dehydration can trigger the onset of genetically based mental health disorders such as schizophrenia. Dehydration has also been shown to have an effect on mood (Armstrong, et. al., 2012). This is because dehydration stresses the brain at an extracellular level by altering the electrolyte concentrations levels (higher salt) and intracellular by increasing the cytokine (molecules that mediate and regulate activities) which effects the behaviors of the cells. Because of changes at the cellular level, cognitive dysfunctions from dehydration may not be reversible (Wilson and Morley, 2003).

Three months out of the year average temperatures in Las Vegas are above 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 Celsius). City-Data.com lists Las Vegas and surrounding areas as having the lowest average relative humidity levels of all US cities with a population of 50,000 or greater. Las Vegas also ranks 12th out of 150 cities throughout the continental United States for being stressed (Hopkins, 2017). Specific areas where Las Vegas ranks near the top for stress include family stress and health and safety stress (Hopkins, 2017). Exercise has been shown to mitigate depression and stress (Knapen, et, al., 2015) by the release of neurotransmitters called endorphins. However, Becker’s Hospital review (2016) ranks Las Vegas in the top ten least fit cities in the United States.

Las Vegas is a city that grew up with the automobile, planned communities, and strip malls. This legacy prevails today with developer determined clusters of homes behind gates and concrete walls, limited connecting green spaces, numerous large swaths of asphalt that make up the many four and six lane roads, and copious islands of strip malls. The result is that Las Vegas leads the nation in heat island effect. Because of the thermal gain from concrete and asphalt with limited number of shade trees, the summer temperatures in Las Vegas have risen 7 degrees Fahrenheit (-14 Celsius) (Lanza and Stone, 2016; Rice, 2014).

Las Vegas and Mental Health

As we begin to look at Las Vegas in the context of mental health concerns, we must consider that the State of Nevada’s two primary revenue sources are mining and tourism. Tax revenues derived from service-based industries, such as entertainment enable the state to offset a large portion of its tax burden thus omitting the need for a state income tax (Prante and Navin, 2016). The Nevada Resorts Association (2014), reports that the tax burden satisfied by tourism and the gaming industry account for nearly 33 percent of the total sales tax burden. This translates to Nevada’s residents and businesses having the lowest tax burdens in the nation. With no income tax, and a temperate climate seven months out of the year, Las Vegas is an attractive retirement destination for those receiving an income from a pension or other forms of retirement funds.

As of 2010, the US Census Bureau states that 12% of the Las Vegas population is over the age of 65 of which 9% have a disability. Senior citizens are often negatively affected by loneliness and isolation. Many become more sexually active (Goldberg, 2009), present with drug and alcohol addictions (Beynon, 2009), and demonstrate addictions to different forms of gambling which have been correlated to negative comorbidities pertaining to mental and physical health (Subramaniam, etc., al., 2015). McNeilly and Burke (2001) state that many senior citizens (aged 65+) pass their leisure time gambling. For those older people seeking periodic adrenaline surges, casino gambling can become a virulent and destructive addiction.

Concurrently, the preponderance of gaming activities within the city make Las Vegas unique because it is a destination where the dreamer can come to “risk it all to win.” Given that males tend to be greater risk takers (Harris, Jenkins and Glaser, 2006) and that most of these dreamers lose everything, it comes as no surprise that single younger males appear in addiction centers with greater frequency (Bernhard and St. John 2012). This loss and failure are thus precursors to other addictions, other risky behaviors and/or the desire to take one’s own life (Bernhard and St. John, 2012).

Mental Health America (Formerly known as the National Mental Health Association) compared 51 sectors of the United States (50 states and the District of Columbia). This comparison shows that Nevada ranks 51 out of 51 (the lowest) for mental health services. In terms of the highest adult population known to a have dependence on drug and alcohol, the state ranks 28 out of 51, and 42 out of 51 for adults who have had serious thoughts of suicide, and 38 out of 51 for people who present with any form of mental illness with unmet needs (Mental Health America, n.d.). These numbers are important because 75% of Nevada’s population lives within the Las Vegas area (Ritter, 2017).

The United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2015) state that when left untreated, mental health conditions can have devastating effects and bring about comorbidities and additional disorders. Some of the outcomes include high levels of stress that can further alter the composition and function of the prefrontal cortex. Hence, once a mental health disorder is discovered, treatment is the best intervention to prevent a cascading decline that can result in destructive behaviors such as acts of mass violence (Metzl and MacLeish 2015), homelessness (Aubry, Nelson, and Tsemberis, 2015), or suicide (Chesney, Goodwin, and Fazel, 2014). The top three concerns within Las Vegas are addiction, suicide, and elder services.

Las Vegas’s Future

The Urban Institute’s Mapping America’s Future website indicates that the future of Nevada is bright. The state as a whole is expected to experience a 20.52% growth in population between 2020 and 2030. The Las Vegas economic zone, which includes adjacent rural areas of Nevada and Northern Arizona which are tied to Las Vegas, is projected to grow by as much as 22.31% between 2020 and 2030. These estimates suggest that one of the youngest cities in the United States will be among the areas with the highest growth. However, this kind of growth in such a short time could bring about social turbulence (McPhearson et, al. 2016). These authors suggest that rapid growth without an emphasis on urban ecology and scientific methods may come at the expense of adequate preparation for natural disasters, availability of good living conditions, and balance between the built and natural elements. Las Vegas currently has a shortage of water, and already implemented water saving measures by drastically reducing green spaces. Increased rock landscaping coupled with fewer shade trees is a reason why Las Vegas is so affected by the heat island effect.

Las Vegas has already experienced some of the negative effects of rapid growth which can be seen in the endless miles of planned development giving way to an automobile dependent community, high asphalt-to-green-space ratios increase the heat island effect, and poor uses of shade trees and other plant material that can aid in the cooling of areas and consequently assist with water conservation. As with other United States Sun Belt cities, Las Vegas has exhibited many political and economic tendencies found in Phoenix, San Antonio, and other metropolises along the “southern rim” (Moehring, 2000). As a resort city, Las Vegas has built a tourist infrastructure remarkably similar to those in Miami Beach and Honolulu. And, as a casino city, has struggled with an abnormally high crime rate similar to Atlantic City in New Jersey. As a smaller and younger city to Los Angeles, Phoenix, San Antonio, etc., an ecological approach would have been to prevent the replication of mistakes made from urban sprawl and to learn from the successes and failures of the respective cities.

The benefits of green spaces have been shown to decrease stress, raise humidity levels, and help compensate for heat island effects. As mentioned, stress, dehydration, and excessive heat can trigger a genetic predisposition to a mental illness and alter the composition of the prefrontal cortex. Within the city of Las Vegas, years of drought and an emphasis on alternate forms of landscaping has led to zero landscaping and the introduction of materials known to have high levels of thermal gain (rock, concrete, and metal).

Regular exercise has been shown to be effective deterrent of depression and obesity. Researchers have raised concerns regarding the connections between childhood obesity and depression (Reeves, et., al. 2008). Active transportation via bicycling, walking, or running is a way to bring exercise into a given population’s daily activities. These activities include going to school, work, or to places of recreation. Kevin Lynch (1960) created the now famous five elements that define a city. In US Sunbelt cities, the elements can be used at micro scales, with each micro scale creating a district within the macro scale. This method would allow for communities to be connected in such a way as to promote active transportation for all age groups.

Once effective green spaces have been included within the urban fabric and connected via safe and reasonable means for active transportation, prosocial areas will likely emerge. Some theorists believe that there is a cyclical relationship between positive social interactions and the release of oxytocin. Campbell (2010) identified a preponderance of research based on attachment and trust, social memory, and fear reduction, all of which lead to a happier overall disposition. This can in turn reduce isolation by the elderly and the formation of healthier social bonds among young people.

The National Alliance on Mental Health’s website (2017) suggests that mental health problems in the United States are increasing. These increases can be attributed to multiple factors that include: better diagnosis, increased awareness by the public, increased numbers of elderly people experiencing cognitive decline, and a rise in homeless populations. Some types of mental health problems such as schizophrenia can be related back to a genetic predisposition (Horvath and Mirnics, 2015) coupled with psychosocial factors. Other mental health conditions have their roots in social discourse (Layous, Chancellor & Lyubomirsky, 2014). Loneliness and isolation are often a precursor for depression (Cacioppo, Hawkley & Thisted, 2010), which can be exacerbated by inadequate provisions of social services.

Within the United States, health service provisions tend to be clustered according to age, gender, ethnicity, and then further clustered according to type of health condition such as psychotic disorders (bipolar disorder and schizophrenia), addiction-based disorders (i.e. alcohol, drug, and sexual activity), and age-related disorders (i.e. changes in cognition, mobility, and sensory detection). Hence, it is not uncommon to find specific social service programs for African American women who are intravenous (I.V.) drug users. This multicluster (ethnic, gender, and condition) approach is an effective method for the allocation and distribution of funds from federal and state agencies, and is effective in the reduction of confounding variables that could invalidate outcome measures. However, this cluster approach presupposes only people that fall within those multicluster parameters require assistance. Provisions for those outside of the clusters are assumed to be without need or low in priority.

Mental health services in the United States tend to be funded through federal and state sponsored grants based on multicluster criteria. This method of grant funding, and the growth of social services that survive from these funds, often leaves gaping holes in the available services. For example, services for drug and alcohol-based addictions may or may not concurrently address other behavior-based addictions, such as sexual or gambling addiction. Drug and alcohol addictions are intertwined with sexual (Sussman, 2017) and other forms of addictions, but that portion of the problem may not be addressed because it exceeds the scope of the grant/funding source.

Mental Health and The Environment

The Biopsychosocial Model is based on the idea that an interaction between biological factors such as genetics and the biochemical alteration at the cellular level, combined with psychological factors related to personality and disposition, and social factors linked to socioeconomics and environment combine to bring about illness or disorder (Engel, 1977). This model supports the idea that designers of the built environment can serve as collaborators in the prevention, rehabilitation, and accommodation of psychobiological illnesses and physical disorders.

Stress and dehydration are examples of psychological and biological predictors of impaired cognition. Wilson and Morley (2003) have shown that severe dehydration can trigger the onset of genetically based mental health disorders such as schizophrenia. Dehydration has also been shown to have an effect on mood (Armstrong, et. al., 2012). This is because dehydration stresses the brain at an extracellular level by altering the electrolyte concentrations levels (higher salt) and intracellular by increasing the cytokine (molecules that mediate and regulate activities) which effects the behaviors of the cells. Because of changes at the cellular level, cognitive dysfunctions from dehydration may not be reversible (Wilson and Morley, 2003).

Three months out of the year average temperatures in Las Vegas are above 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 Celsius). City-Data.com lists Las Vegas and surrounding areas as having the lowest average relative humidity levels of all US cities with a population of 50,000 or greater. Las Vegas also ranks 12th out of 150 cities throughout the continental United States for being stressed (Hopkins, 2017). Specific areas where Las Vegas ranks near the top for stress include family stress and health and safety stress (Hopkins, 2017). Exercise has been shown to mitigate depression and stress (Knapen, et, al., 2015) by the release of neurotransmitters called endorphins. However, Becker’s Hospital review (2016) ranks Las Vegas in the top ten least fit cities in the United States.

Las Vegas is a city that grew up with the automobile, planned communities, and strip malls. This legacy prevails today with developer determined clusters of homes behind gates and concrete walls, limited connecting green spaces, numerous large swaths of asphalt that make up the many four and six lane roads, and copious islands of strip malls. The result is that Las Vegas leads the nation in heat island effect. Because of the thermal gain from concrete and asphalt with limited number of shade trees, the summer temperatures in Las Vegas have risen 7 degrees Fahrenheit (-14 Celsius) (Lanza and Stone, 2016; Rice, 2014).

Las Vegas and Mental Health

As we begin to look at Las Vegas in the context of mental health concerns, we must consider that the State of Nevada’s two primary revenue sources are mining and tourism. Tax revenues derived from service-based industries, such as entertainment enable the state to offset a large portion of its tax burden thus omitting the need for a state income tax (Prante and Navin, 2016). The Nevada Resorts Association (2014), reports that the tax burden satisfied by tourism and the gaming industry account for nearly 33 percent of the total sales tax burden. This translates to Nevada’s residents and businesses having the lowest tax burdens in the nation. With no income tax, and a temperate climate seven months out of the year, Las Vegas is an attractive retirement destination for those receiving an income from a pension or other forms of retirement funds.

As of 2010, the US Census Bureau states that 12% of the Las Vegas population is over the age of 65 of which 9% have a disability. Senior citizens are often negatively affected by loneliness and isolation. Many become more sexually active (Goldberg, 2009), present with drug and alcohol addictions (Beynon, 2009), and demonstrate addictions to different forms of gambling which have been correlated to negative comorbidities pertaining to mental and physical health (Subramaniam, etc., al., 2015). McNeilly and Burke (2001) state that many senior citizens (aged 65+) pass their leisure time gambling. For those older people seeking periodic adrenaline surges, casino gambling can become a virulent and destructive addiction.

Concurrently, the preponderance of gaming activities within the city make Las Vegas unique because it is a destination where the dreamer can come to “risk it all to win.” Given that males tend to be greater risk takers (Harris, Jenkins and Glaser, 2006) and that most of these dreamers lose everything, it comes as no surprise that single younger males appear in addiction centers with greater frequency (Bernhard and St. John 2012). This loss and failure are thus precursors to other addictions, other risky behaviors and/or the desire to take one’s own life (Bernhard and St. John, 2012).

Mental Health America (Formerly known as the National Mental Health Association) compared 51 sectors of the United States (50 states and the District of Columbia). This comparison shows that Nevada ranks 51 out of 51 (the lowest) for mental health services. In terms of the highest adult population known to a have dependence on drug and alcohol, the state ranks 28 out of 51, and 42 out of 51 for adults who have had serious thoughts of suicide, and 38 out of 51 for people who present with any form of mental illness with unmet needs (Mental Health America, n.d.). These numbers are important because 75% of Nevada’s population lives within the Las Vegas area (Ritter, 2017).

The United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2015) state that when left untreated, mental health conditions can have devastating effects and bring about comorbidities and additional disorders. Some of the outcomes include high levels of stress that can further alter the composition and function of the prefrontal cortex. Hence, once a mental health disorder is discovered, treatment is the best intervention to prevent a cascading decline that can result in destructive behaviors such as acts of mass violence (Metzl and MacLeish 2015), homelessness (Aubry, Nelson, and Tsemberis, 2015), or suicide (Chesney, Goodwin, and Fazel, 2014). The top three concerns within Las Vegas are addiction, suicide, and elder services.

Las Vegas’s Future

The Urban Institute’s Mapping America’s Future website indicates that the future of Nevada is bright. The state as a whole is expected to experience a 20.52% growth in population between 2020 and 2030. The Las Vegas economic zone, which includes adjacent rural areas of Nevada and Northern Arizona which are tied to Las Vegas, is projected to grow by as much as 22.31% between 2020 and 2030. These estimates suggest that one of the youngest cities in the United States will be among the areas with the highest growth. However, this kind of growth in such a short time could bring about social turbulence (McPhearson et, al. 2016). These authors suggest that rapid growth without an emphasis on urban ecology and scientific methods may come at the expense of adequate preparation for natural disasters, availability of good living conditions, and balance between the built and natural elements. Las Vegas currently has a shortage of water, and already implemented water saving measures by drastically reducing green spaces. Increased rock landscaping coupled with fewer shade trees is a reason why Las Vegas is so affected by the heat island effect.

Las Vegas has already experienced some of the negative effects of rapid growth which can be seen in the endless miles of planned development giving way to an automobile dependent community, high asphalt-to-green-space ratios increase the heat island effect, and poor uses of shade trees and other plant material that can aid in the cooling of areas and consequently assist with water conservation. As with other United States Sun Belt cities, Las Vegas has exhibited many political and economic tendencies found in Phoenix, San Antonio, and other metropolises along the “southern rim” (Moehring, 2000). As a resort city, Las Vegas has built a tourist infrastructure remarkably similar to those in Miami Beach and Honolulu. And, as a casino city, has struggled with an abnormally high crime rate similar to Atlantic City in New Jersey. As a smaller and younger city to Los Angeles, Phoenix, San Antonio, etc., an ecological approach would have been to prevent the replication of mistakes made from urban sprawl and to learn from the successes and failures of the respective cities.

The benefits of green spaces have been shown to decrease stress, raise humidity levels, and help compensate for heat island effects. As mentioned, stress, dehydration, and excessive heat can trigger a genetic predisposition to a mental illness and alter the composition of the prefrontal cortex. Within the city of Las Vegas, years of drought and an emphasis on alternate forms of landscaping has led to zero landscaping and the introduction of materials known to have high levels of thermal gain (rock, concrete, and metal).

Regular exercise has been shown to be effective deterrent of depression and obesity. Researchers have raised concerns regarding the connections between childhood obesity and depression (Reeves, et., al. 2008). Active transportation via bicycling, walking, or running is a way to bring exercise into a given population’s daily activities. These activities include going to school, work, or to places of recreation. Kevin Lynch (1960) created the now famous five elements that define a city. In US Sunbelt cities, the elements can be used at micro scales, with each micro scale creating a district within the macro scale. This method would allow for communities to be connected in such a way as to promote active transportation for all age groups.

Once effective green spaces have been included within the urban fabric and connected via safe and reasonable means for active transportation, prosocial areas will likely emerge. Some theorists believe that there is a cyclical relationship between positive social interactions and the release of oxytocin. Campbell (2010) identified a preponderance of research based on attachment and trust, social memory, and fear reduction, all of which lead to a happier overall disposition. This can in turn reduce isolation by the elderly and the formation of healthier social bonds among young people.

Method

This was a qualitative study based on key informant interviews identified by non-probability snowball sampling methods. The University of Washington’s Key Informant Interview Handbook identified the benefits of key informant interviews, because they provide a means to acquire information from knowledgeable people and are inexpensive. However, they also note that key informant interviews are vulnerable to bias and difficult to ensure the validity of results. The sampling method used to identify key informants was a non-probability snowball sampling technique. This method is based on contact tracing which is used in public health to identify patient zero. Snowball sampling uses a fundamental linear premise. However, instead of gathering participants from one direction like contact tracing, this method gathers participants from multiple perspectives identified by a first participant referring others (Sadler, et. al., 2010). In this study the first person was a City Planner. This profession was chosen to begin the sample pool because city planners tend to interface with architects, community health agencies and elected officials.

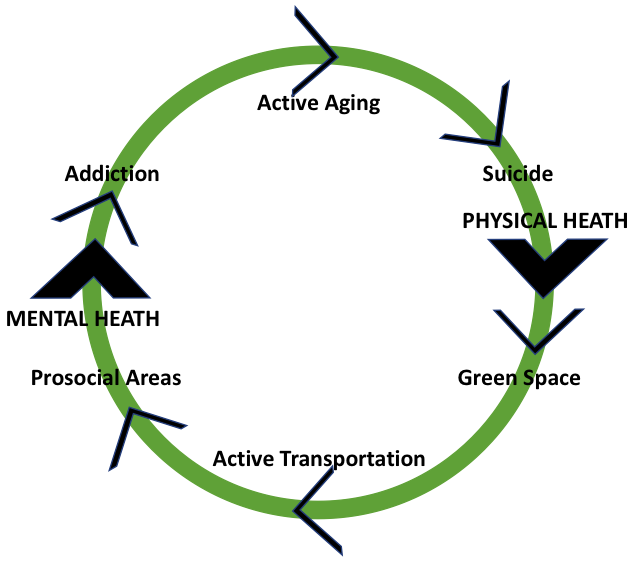

This study used questions to facilitate a qualitative study that measured if and to what degree city employees, architects and community health professionals were able to conceptualize the design of the built environment in relation to physical and mental health. The built environment’s indices included the role of green spaces, active transportation, and pro social areas. These elements were then used as points of reference to address addiction, suicide and active aging.

This study used questions to facilitate a qualitative study that measured if and to what degree city employees, architects and community health professionals were able to conceptualize the design of the built environment in relation to physical and mental health. The built environment’s indices included the role of green spaces, active transportation, and pro social areas. These elements were then used as points of reference to address addiction, suicide and active aging.

Figure 1: Relationships between urban environment and health

In this study, health and wellbeing were correlated to physical and mental health. Questions centered on the development and influences of green spaces, active transportation, and the presence of prosocial areas in relation to issues of addiction, suicide, and active aging. Responses from the interviews were then correlated back to the literature review.

Participants

The goal of this study was to secure six participants from each of the four clusters of professional or practicing architects, city planners, community health personnel and policy makers (elected officials). These numbers were chosen because a sample pool of 24 was within the University of Washington’s Key Informant Interview Handbook’s recommendation of 15-35 participants.

In total, eight professionals from community health, seven from city planning and parks and recreation (collectively referred to as city employees), and four from architecture were secured. Despite best efforts, no policy makers participated in the study. Some of the individuals never responded to the request for interview, others declined the interview because they lacked time, and a third group declined the interview because they were uncomfortable commenting on the subject matter. Our sample pool was reduced from the goal of 24 to 19, and the sample was heavily skewed toward city employees and community health professionals. The cluster group of city planners was expanded because some of the areas of research extended into Parks and Recreation.

Because of the relationships between city and elected officials with each of the professions included in this study, all participants were guaranteed absolute anonymity. No names, titles, or any other identifying factor (including direct quotes from which word choice and sentence syntax could be used as an identifier) was included in the data acquisition or discussion. Participants did range from low-level positions to management and leadership positions. Upon review the results, it was determined that position level did not alter the overall results one-way or the other. Thus, as an added level of privacy we do not state how many people from each position level was included in the interview.

Implementation

Interviews took place via telephone and in person. Participants were asked specific questions with broad-based terms such as the word addiction. This was done to identify where the interviewee would take the conversation with the premise that where a person took the conversation would reveal areas of importance. Respondents often asked for greater clarification and/or operational definitions, but the interviewer only responded by telling the interviewee to answer the question that best reflect their thoughts.

The first bank of questions was a series of questions related to the perceived value of having access to nature, active transportation, and pro-social areas, such as parks, pocket parks, and hubs for socialization, as a means to assist with the prevention, treatment, or accommodation for addictive behaviors, suicide, and healthy aging. Questions were left broad and with minimal specificity in order to allow the interviewee to make interpretations from him or herself, and to freely elaborate on his or her thoughts.

The next bank of questions pertained to the identification of known projects within the city that had been specifically designed to address mental health concerns. The idea behind this question was to see the interviewee’s point of reference. The third bank of questions centered on opinions of the interviewees for architects, city planners, or community health professionals to specifically include methods of design as a means to help improve physical and mental health within the city. These questions were followed up with a question pertaining to knowledge of incentive programs for the design of the built environment known to assist with the prevention, rehabilitation, or accommodation of physical and mental health concerns.

The next set of questions inquired about the beliefs of interviewees toward the priority of addressing mental health through urban design initiatives and official guidelines, recommendations, policies or rules that govern design. These questions were followed with a question about the perceived interest of developing projects specifically intended to help improve mental health through environmental design, and the identification of specific developments known to improve mental health.

A final question sought to discover personal thoughts related to the encouragement or prevention of local professionals from considering environmental design as an effective strategy to address mental health.

Participants

The goal of this study was to secure six participants from each of the four clusters of professional or practicing architects, city planners, community health personnel and policy makers (elected officials). These numbers were chosen because a sample pool of 24 was within the University of Washington’s Key Informant Interview Handbook’s recommendation of 15-35 participants.

In total, eight professionals from community health, seven from city planning and parks and recreation (collectively referred to as city employees), and four from architecture were secured. Despite best efforts, no policy makers participated in the study. Some of the individuals never responded to the request for interview, others declined the interview because they lacked time, and a third group declined the interview because they were uncomfortable commenting on the subject matter. Our sample pool was reduced from the goal of 24 to 19, and the sample was heavily skewed toward city employees and community health professionals. The cluster group of city planners was expanded because some of the areas of research extended into Parks and Recreation.

Because of the relationships between city and elected officials with each of the professions included in this study, all participants were guaranteed absolute anonymity. No names, titles, or any other identifying factor (including direct quotes from which word choice and sentence syntax could be used as an identifier) was included in the data acquisition or discussion. Participants did range from low-level positions to management and leadership positions. Upon review the results, it was determined that position level did not alter the overall results one-way or the other. Thus, as an added level of privacy we do not state how many people from each position level was included in the interview.

Implementation

Interviews took place via telephone and in person. Participants were asked specific questions with broad-based terms such as the word addiction. This was done to identify where the interviewee would take the conversation with the premise that where a person took the conversation would reveal areas of importance. Respondents often asked for greater clarification and/or operational definitions, but the interviewer only responded by telling the interviewee to answer the question that best reflect their thoughts.

The first bank of questions was a series of questions related to the perceived value of having access to nature, active transportation, and pro-social areas, such as parks, pocket parks, and hubs for socialization, as a means to assist with the prevention, treatment, or accommodation for addictive behaviors, suicide, and healthy aging. Questions were left broad and with minimal specificity in order to allow the interviewee to make interpretations from him or herself, and to freely elaborate on his or her thoughts.

The next bank of questions pertained to the identification of known projects within the city that had been specifically designed to address mental health concerns. The idea behind this question was to see the interviewee’s point of reference. The third bank of questions centered on opinions of the interviewees for architects, city planners, or community health professionals to specifically include methods of design as a means to help improve physical and mental health within the city. These questions were followed up with a question pertaining to knowledge of incentive programs for the design of the built environment known to assist with the prevention, rehabilitation, or accommodation of physical and mental health concerns.

The next set of questions inquired about the beliefs of interviewees toward the priority of addressing mental health through urban design initiatives and official guidelines, recommendations, policies or rules that govern design. These questions were followed with a question about the perceived interest of developing projects specifically intended to help improve mental health through environmental design, and the identification of specific developments known to improve mental health.

A final question sought to discover personal thoughts related to the encouragement or prevention of local professionals from considering environmental design as an effective strategy to address mental health.

Results

City Planners

Four people from city planning and three people from parks and recreation participated in the study. These seven individuals are collectively referred to as city employees. City employees agreed that access to nature, active transportation, and pro-social areas are important for physical health and active aging. When it came to the specific health conditions of addictive behaviors and suicide prevention, they leaped from addiction to homelessness and drug addiction. Neither group of city employees was able to find a connection between the designed environment and suicide prevention.

Interestingly, city planners identified several examples of privately funded organizations of where addictive behaviors (homeless shelters) could receive treatment. Three of the city planners continually addressed addiction and suicide via support services and had a difficult time understanding the relationship between the design of urban spaces and mental health concerns. In terms of healthy aging, both the city planners and parks and recreation professionals tended to gravitate to the initiatives completed by developers as part of the land development process. When pressed, the city planners started to speak of future planned initiatives.

Both city planners and architects believe that architects actively design their projects to help improve physical health, but were not sure about mental health. They did believe that community health professionals actively consider or promote environmental design as a means to help improve physical and mental health. Conversely, they did not believe that policy makers consider, promote, or make environmental design a priority to help improve physical and mental health.

While the city employees were not aware of any incentive programs that would support environmental interventions for physical or mental health, they do believe that it is a priority for architects and community health professionals. However, neither city planners nor parks and recreation professionals knew of any current official guidelines, recommendations, policies or rules that include mental health in urban design for Las Vegas. The four city planners all highlighted the city’s strategic plan to be completed by 2045.

City planners and parks and recreation professionals do believe that there is interest by architects and community health professionals to develop projects to help improve mental health through environmental design, but the city planners were quick to identify limited funding and lack of legislative support to assist in bringing these interests to fruition. This lack of legislative support stems from policy makers either not considering or making the design of urban environments a priority.

Both the city planners and parks and recreation professionals did identify an example that they thought would improve mental health through urban design, but the examples were either not design based, or were done by specific organizational funds (i.e. Catholic Charities) on organization-owned property, not city property paid for by public funds. City planners and parks and recreation professionals indicated a desire to do more, but lack support. A couple of interviewees indicated that they lacked the knowledge of what could be done, and if they lacked this knowledge, they felt confident that local architects, community health professionals and policy makers also lack this knowledge.

Architects

Of all groups interviewed, architects represented the smallest cluster with only four interviewees. One was an educator, one was an educator and practitioner, and two were practitioners. Overall, the architects do believe that access to nature, active transportation, and pro-social areas are important to physical and mental health, but when asked about specific issues such as addictive behaviors and suicide prevention they were unsure. Two of the architects interviewed did believe that access to nature, active transportation, and pro-social areas would promote healthy aging.

The architects thought that city planners did not actively look for, or plan projects, to help improve physical health; only one thought that city planners did actively look for, or plan projects, to help improve mental health. Three of the architects’ thought that community health professionals did actively look for, or plan projects, to help improve physical and mental health. The remaining interviewees did not have an opinion. All four architects did agree that they do not believe that policy makers are involved in the identification or planning of projects to help improve physical and mental health. All four agreed that they did not know of any incentive programs that would support environmental interventions for physical or mental health.

When asked for examples within the city of Las Vegas where addictive behaviors, suicide prevention or healthy aging have been incorporated into the public urban landscape, none of the architects could identify any that were publicly sponsored and on public lands. The architects did mention initiatives on private property, and parks located in the Las Vegas suburbs. Similarly, the architects were not aware of any current official guidelines, recommendations, policies or rules, or existing development on public property that specifically addressed mental health in urban design.

The architects interviewed do believe that mental health is a priority by individual city planners and community health professionals, but not as a priority for the city planning office to initiate urban design initiatives. Three of the architects stated this is because the city-planning department doesn’t have the support of the policy makers. The architects further did not know how community health professionals would be involved in urban design initiatives from the inception phase, and as such did not believe it was within their scope to make mental health a priority in terms of urban design initiatives.

The architects do believe that there is an interest by city planners and community health professionals to develop and implement projects intended to help improve mental health through environmental design. However, the architects were not sure if policy makers shared this interest. As one architect indicated, policy makers are interested in physical health and much less about mental health concerns. They believe that community health professionals and city planners are impeded from considering environmental design as an effective strategy to address mental health because of a lack of funding and support from policy makers.

Community Health Professionals

A total of eight-community health professionals were interviewed for this project. One was employed by a public agency, one was involved in a community-based organization that serves the homeless population, two were in a counseling profession but worked in higher education, and four were in leadership positions for community-based organization focused on addiction and recovery. The general consensus among community health professionals was that city employees and architects are aware of design methods that could be used to address physical and mental health issues, but are limited in what they can do because policy makers and private sources often limit the funding.

The community health professionals believe that free and easy access to natural environments, active transportation methods, and pro-social areas are important elements of the urban environment and can assist with the prevention and treatment of addictive behaviors, suicide prevention, and healthy aging. A few of the interviewees were able to cite one or two examples of ideal spaces, but these spaces were privately owned and operated. None were able to identify an example of a public space within the city of Las Vegas where addictive behaviors, suicide prevention or healthy aging were included as part of the design process.

The majority of interviewees stated that they believe architects and city employees actively design, look for, or specifically plan projects to help improve physical and mental health. They also believe there is an interest on the part of architects and city employees to develop projects to help improve mental health through environmental design. However, three of the five indicated that they do not believe that the intentions of city employees or architects could be followed through with because of financial reasons. Three of interviewees had no knowledge from which they could respond.

Many of the community health professionals do believe that issues of mental health are a priority for urban design initiatives within Las Vegas by architects and city employees. However, they do not think that the designs of the urban environment, as a means to address physical and mental health, are a priority for policy makers, and were not able to recall any examples of specific publicly sponsored developments intended to improve mental health through urban design. To this end, none of the community health professionals were aware of any official guidelines, recommendations, policies or rules, or any incentive programs what would support urban design initiatives intended to address physical and mental health issues.

Community health professionals also believed that with further education, that policymakers would become more interested in the design of urban environment to address physical and mental health issues. However, as it stands today, the consensus among community health professionals is that policy makers do not fully understand the breadth of initiatives that can be implemented to have a positive effect on physical and mental health issues with the city of Las Vegas. Interviewees thus suggested that greater education should be directed at the general population in order to bring about greater public pressure to elected officials about the merits of urban design to assist with physical and mental health concerns.

Four people from city planning and three people from parks and recreation participated in the study. These seven individuals are collectively referred to as city employees. City employees agreed that access to nature, active transportation, and pro-social areas are important for physical health and active aging. When it came to the specific health conditions of addictive behaviors and suicide prevention, they leaped from addiction to homelessness and drug addiction. Neither group of city employees was able to find a connection between the designed environment and suicide prevention.

Interestingly, city planners identified several examples of privately funded organizations of where addictive behaviors (homeless shelters) could receive treatment. Three of the city planners continually addressed addiction and suicide via support services and had a difficult time understanding the relationship between the design of urban spaces and mental health concerns. In terms of healthy aging, both the city planners and parks and recreation professionals tended to gravitate to the initiatives completed by developers as part of the land development process. When pressed, the city planners started to speak of future planned initiatives.

Both city planners and architects believe that architects actively design their projects to help improve physical health, but were not sure about mental health. They did believe that community health professionals actively consider or promote environmental design as a means to help improve physical and mental health. Conversely, they did not believe that policy makers consider, promote, or make environmental design a priority to help improve physical and mental health.

While the city employees were not aware of any incentive programs that would support environmental interventions for physical or mental health, they do believe that it is a priority for architects and community health professionals. However, neither city planners nor parks and recreation professionals knew of any current official guidelines, recommendations, policies or rules that include mental health in urban design for Las Vegas. The four city planners all highlighted the city’s strategic plan to be completed by 2045.

City planners and parks and recreation professionals do believe that there is interest by architects and community health professionals to develop projects to help improve mental health through environmental design, but the city planners were quick to identify limited funding and lack of legislative support to assist in bringing these interests to fruition. This lack of legislative support stems from policy makers either not considering or making the design of urban environments a priority.

Both the city planners and parks and recreation professionals did identify an example that they thought would improve mental health through urban design, but the examples were either not design based, or were done by specific organizational funds (i.e. Catholic Charities) on organization-owned property, not city property paid for by public funds. City planners and parks and recreation professionals indicated a desire to do more, but lack support. A couple of interviewees indicated that they lacked the knowledge of what could be done, and if they lacked this knowledge, they felt confident that local architects, community health professionals and policy makers also lack this knowledge.

Architects

Of all groups interviewed, architects represented the smallest cluster with only four interviewees. One was an educator, one was an educator and practitioner, and two were practitioners. Overall, the architects do believe that access to nature, active transportation, and pro-social areas are important to physical and mental health, but when asked about specific issues such as addictive behaviors and suicide prevention they were unsure. Two of the architects interviewed did believe that access to nature, active transportation, and pro-social areas would promote healthy aging.

The architects thought that city planners did not actively look for, or plan projects, to help improve physical health; only one thought that city planners did actively look for, or plan projects, to help improve mental health. Three of the architects’ thought that community health professionals did actively look for, or plan projects, to help improve physical and mental health. The remaining interviewees did not have an opinion. All four architects did agree that they do not believe that policy makers are involved in the identification or planning of projects to help improve physical and mental health. All four agreed that they did not know of any incentive programs that would support environmental interventions for physical or mental health.

When asked for examples within the city of Las Vegas where addictive behaviors, suicide prevention or healthy aging have been incorporated into the public urban landscape, none of the architects could identify any that were publicly sponsored and on public lands. The architects did mention initiatives on private property, and parks located in the Las Vegas suburbs. Similarly, the architects were not aware of any current official guidelines, recommendations, policies or rules, or existing development on public property that specifically addressed mental health in urban design.

The architects interviewed do believe that mental health is a priority by individual city planners and community health professionals, but not as a priority for the city planning office to initiate urban design initiatives. Three of the architects stated this is because the city-planning department doesn’t have the support of the policy makers. The architects further did not know how community health professionals would be involved in urban design initiatives from the inception phase, and as such did not believe it was within their scope to make mental health a priority in terms of urban design initiatives.

The architects do believe that there is an interest by city planners and community health professionals to develop and implement projects intended to help improve mental health through environmental design. However, the architects were not sure if policy makers shared this interest. As one architect indicated, policy makers are interested in physical health and much less about mental health concerns. They believe that community health professionals and city planners are impeded from considering environmental design as an effective strategy to address mental health because of a lack of funding and support from policy makers.

Community Health Professionals

A total of eight-community health professionals were interviewed for this project. One was employed by a public agency, one was involved in a community-based organization that serves the homeless population, two were in a counseling profession but worked in higher education, and four were in leadership positions for community-based organization focused on addiction and recovery. The general consensus among community health professionals was that city employees and architects are aware of design methods that could be used to address physical and mental health issues, but are limited in what they can do because policy makers and private sources often limit the funding.

The community health professionals believe that free and easy access to natural environments, active transportation methods, and pro-social areas are important elements of the urban environment and can assist with the prevention and treatment of addictive behaviors, suicide prevention, and healthy aging. A few of the interviewees were able to cite one or two examples of ideal spaces, but these spaces were privately owned and operated. None were able to identify an example of a public space within the city of Las Vegas where addictive behaviors, suicide prevention or healthy aging were included as part of the design process.

The majority of interviewees stated that they believe architects and city employees actively design, look for, or specifically plan projects to help improve physical and mental health. They also believe there is an interest on the part of architects and city employees to develop projects to help improve mental health through environmental design. However, three of the five indicated that they do not believe that the intentions of city employees or architects could be followed through with because of financial reasons. Three of interviewees had no knowledge from which they could respond.

Many of the community health professionals do believe that issues of mental health are a priority for urban design initiatives within Las Vegas by architects and city employees. However, they do not think that the designs of the urban environment, as a means to address physical and mental health, are a priority for policy makers, and were not able to recall any examples of specific publicly sponsored developments intended to improve mental health through urban design. To this end, none of the community health professionals were aware of any official guidelines, recommendations, policies or rules, or any incentive programs what would support urban design initiatives intended to address physical and mental health issues.

Community health professionals also believed that with further education, that policymakers would become more interested in the design of urban environment to address physical and mental health issues. However, as it stands today, the consensus among community health professionals is that policy makers do not fully understand the breadth of initiatives that can be implemented to have a positive effect on physical and mental health issues with the city of Las Vegas. Interviewees thus suggested that greater education should be directed at the general population in order to bring about greater public pressure to elected officials about the merits of urban design to assist with physical and mental health concerns.

Discussion

The review of literature demonstrates clear lines between urban planning initiatives and prevention of select mental health concerns. Similarly, the research demonstrates the positive effects of active transportation and active aging on the release of endorphins thus assisting with the prevention and even rehabilitation of depression. Active transportation and prosocial areas also helps to mitigate cravings for adrenaline surges. This helps to thwart destruction behaviors associated with depression and addiction.

The City of Las Vegas follows the state of Nevada’s Libertarian culture of self reliance and governance. This means that communities such as Summerlin (a Large Master Plan community) has implemented many beneficial initiatives that include center tree lined and desert landscape medians and causeways. While the base of these spaces are rock which has a high thermal gain, they try to plant low water items that sprawl. This, in combination with the limited shade trees helps to reduce the sun's contact with the rock. It’s important to note that Summerlin is a very wealthy community, and these initiatives are funded by association dues and special assessments to the residents of new developments. These initiatives are not uniform throughout the city.

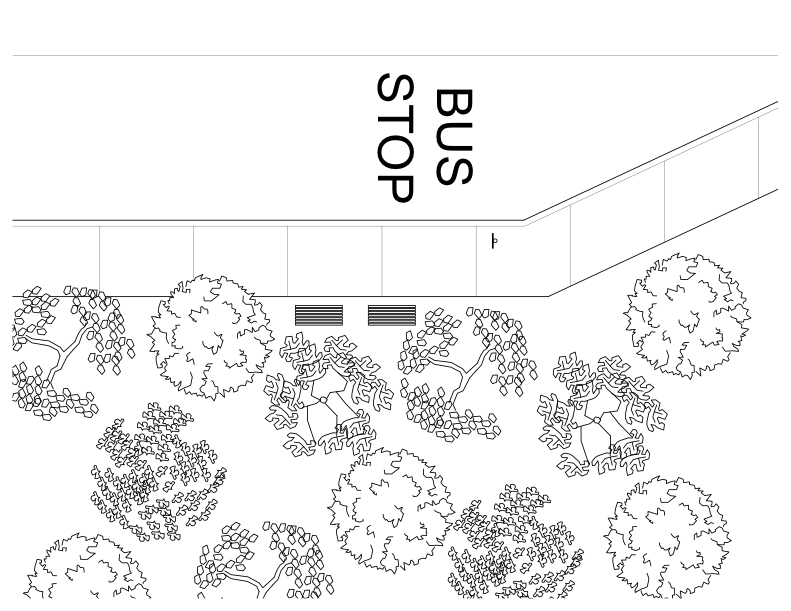

There are various opportunities for Las Vegas. A simple idea is an initiative that transforms bus stops into pocket parks. In hot desert of Las Vegas these pocket parks could become oases that promote access to green space and can become prosocial areas.

The City of Las Vegas follows the state of Nevada’s Libertarian culture of self reliance and governance. This means that communities such as Summerlin (a Large Master Plan community) has implemented many beneficial initiatives that include center tree lined and desert landscape medians and causeways. While the base of these spaces are rock which has a high thermal gain, they try to plant low water items that sprawl. This, in combination with the limited shade trees helps to reduce the sun's contact with the rock. It’s important to note that Summerlin is a very wealthy community, and these initiatives are funded by association dues and special assessments to the residents of new developments. These initiatives are not uniform throughout the city.

There are various opportunities for Las Vegas. A simple idea is an initiative that transforms bus stops into pocket parks. In hot desert of Las Vegas these pocket parks could become oases that promote access to green space and can become prosocial areas.

Figure 2: Bus stops transformed into pocket parks

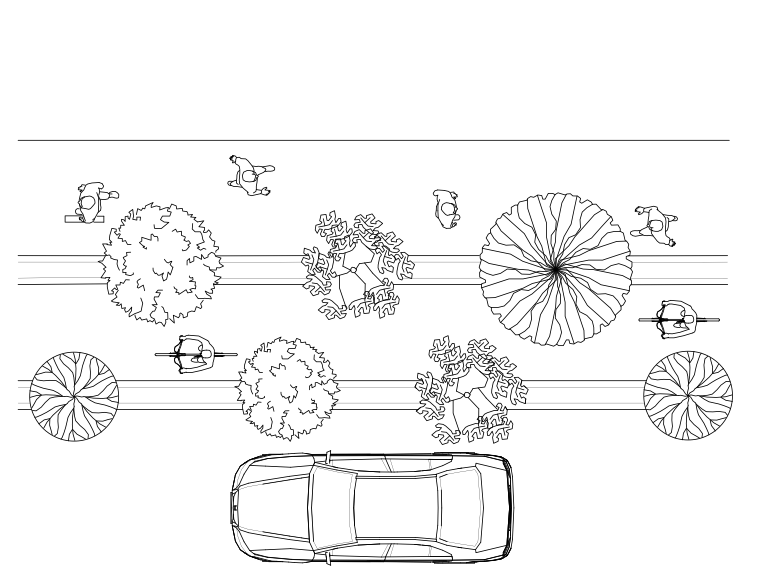

A second idea is the conversion of one lane into an alternative transportation lane. Older people can ride golf carts or take leisurely walks. Young people and adults could use these lanes for bicycling and jogging. This initiative will facilitate activity, increase fitness, and serve as prosocial areas. Two important factors for this latter observation is that the separate lane would require a physical barrier such as a tree-lined median between automobile traffic and the bicycling and pedestrian area. The introduction of shade trees would help reduce direct sun exposure, and encourage more people to engage in the active transportation.

Figure 3: Alternative transportation lanes

The second stage of the research was based on the interviews. While each profession had vast reservoirs of knowledge none of them were able to identify clear initiatives that could augment the role of mental heath providers with methods on environmental design. This may be a consequence of the professional being focused on day-to-day responsibilities. While specific connections were easily made, every group did believe that green spaces, active transportation and prosocial spaces could have a positive effect on mental health. However, gaps in knowledge will need to be filled before specific initiatives can be explored.

Another interesting factor revealed from the key informant interview was the participants’ continued reference to a lack of funding, and that bulk of their day-to-day jobs is concentrated in singular general areas. Many commented that these realities prevent them from doing research that could lead to better outcomes, and instead are focused on the current proven outcomes.

The review of literature has shown that mental health concerns can be prevented and accommodated through environmental planning techniques. Architects, city employees, and community health professionals all agree that there is a connection between the built environment and mental health, but freely admit that they are not sure what those connections are. Also, the interviews revealed a need for continuing education workshops intended to fill the gaps between all professions so that a more comprehensive approach can be taken to solve the growing crisis of mental health.

Another interesting factor revealed from the key informant interview was the participants’ continued reference to a lack of funding, and that bulk of their day-to-day jobs is concentrated in singular general areas. Many commented that these realities prevent them from doing research that could lead to better outcomes, and instead are focused on the current proven outcomes.

The review of literature has shown that mental health concerns can be prevented and accommodated through environmental planning techniques. Architects, city employees, and community health professionals all agree that there is a connection between the built environment and mental health, but freely admit that they are not sure what those connections are. Also, the interviews revealed a need for continuing education workshops intended to fill the gaps between all professions so that a more comprehensive approach can be taken to solve the growing crisis of mental health.

Strength, Weakness, Opportunity and Threat Discussion

The geographic location of Las Vegas makes the city relatively isolated. Carson City (the capital of Nevada) and Reno are about a seven-hour drive, Los Angeles and Phoenix are about a five-hour drive, and Salt Lake City is about six hours away. This isolation means that the city grew with relatively no strong checks and balances from surrounding areas. This isolation is a strength because the city was able to evolve on its own and without a lot of restrictions from surrounding areas. However, the relative isolation also served as a weakness because there was no real-time exploration of ideas that may not have been ideal for Las Vegas.

A threat to the city’s evolution was that its significant growth periods came at time when cities were being designed around the automobile. This caused the development of multi-lane parkways, boulevards, and thoroughfares. Coupled with the preponderance of gated communities, Las Vegas lacks significant and diverse social cohesion. This leads to further threats of a transient population and increased risk for the onset of mental health disorders that include increased risk of suicide, engagement in addictive behaviors, and reduced opportunities for active aging.

Las Vegas is unique from other cities in the United States because many of the mistakes could be rectified through city planning-driven initiatives. With insights from a team of visionary designers, the multi-lane roads could be reconfigured, many of the vacant lands could be reserved for public parks that host pop-up events, and the strip malls could be recast as desert oases. The 2045 downtown master plan will provide many opportunities for the city. A threat to these opportunities is that a plan so far into the future could result in many of authors and drivers of change will have retired or passed away, and social evolution happens on a daily basis. Thus, a plan forged early in the 2000’s may not have relevance in the middle of the century.

The issue of mental illness in the United States has become a growing and omnipresent problem. Las Vegas is no different than many of these cities. Thus one weakness is the current emphasis with planning departments, public officials, and healthcare providers to address symptoms and not the disease. Homelessness is a symptom many cities experience. Mental illness is the causation for many who are homeless. Suicide, addiction, and aging in isolation are all symptoms of a growing mental health concern. Lack of green spaces, places of impromptu social gathering, and active transportation are all included into the purview of urban design, which thus provides many opportunities to address the growing mental health concern.

Limitations (and Further Research)

The principle investigator (P.I.) for this research was new to the Las Vegas area, which may have negatively affected participation rates. Having a limited exposure, with limited contacts meant that the benefits of snowball sampling might have been impeded. In addition, because the P.I. was an outsider, responses may have been sanitized or skewed to the positive. In order to determine if these factors did have an influence the study will need to be replicated at a later date.

Another limitation of this study was boundary delineations. It was difficult to contain this study to the city of Las Vegas. For example, neither the University of Nevada Las Vegas nor the world-renowned strip that defines the skyline and the city are actually in the city limits of Las Vegas. Also, a significant portion of Las Vegas is occupied by the master planned community of Summerlin, which has well defined board that yields significant power and influence over development within that area. When conducting the interviews, the greater area of Clark County kept getting included in the city, and the conceptualization of the city perceptually extended beyond its borders into Clark County. This is a phenomenon common in the U.S. southwest. Many people claim to live in either Los Angeles or San Diego when in actuality they live in a defined city within the respective counties. The blurring of boundaries and areas of responsibility within Las Vegas did make this project more difficult to navigate. To address this concern, it might be relevant to replicate the study but increase the target boundaries to all of Clark County.

As with all self-report data, the information obtained is heavily influenced by participant perception. Hence, acquiring additional background information pertaining to the length of time the participant has lived in Las Vegas, where they actually live, and if they have had any significant and meaningful exposure to other cities might help to provide further information pertaining their responses. To this end, replication of the study would require more detailed background of the respondents to determine their frame of reference.

While the goal was to include policy makers, a limitation of this study is that they were not included. Policy makers tend to set cultural paradigms and social agendas. By not having input from this population it is not known if it is a lack of education that causes gaps or if there some alternate strategy that has not been unveiled. Clearly, replicating this study with the inclusion of policy makers would be advantageous and add to a greater understanding of the results.

The geographic location of Las Vegas makes the city relatively isolated. Carson City (the capital of Nevada) and Reno are about a seven-hour drive, Los Angeles and Phoenix are about a five-hour drive, and Salt Lake City is about six hours away. This isolation means that the city grew with relatively no strong checks and balances from surrounding areas. This isolation is a strength because the city was able to evolve on its own and without a lot of restrictions from surrounding areas. However, the relative isolation also served as a weakness because there was no real-time exploration of ideas that may not have been ideal for Las Vegas.

A threat to the city’s evolution was that its significant growth periods came at time when cities were being designed around the automobile. This caused the development of multi-lane parkways, boulevards, and thoroughfares. Coupled with the preponderance of gated communities, Las Vegas lacks significant and diverse social cohesion. This leads to further threats of a transient population and increased risk for the onset of mental health disorders that include increased risk of suicide, engagement in addictive behaviors, and reduced opportunities for active aging.

Las Vegas is unique from other cities in the United States because many of the mistakes could be rectified through city planning-driven initiatives. With insights from a team of visionary designers, the multi-lane roads could be reconfigured, many of the vacant lands could be reserved for public parks that host pop-up events, and the strip malls could be recast as desert oases. The 2045 downtown master plan will provide many opportunities for the city. A threat to these opportunities is that a plan so far into the future could result in many of authors and drivers of change will have retired or passed away, and social evolution happens on a daily basis. Thus, a plan forged early in the 2000’s may not have relevance in the middle of the century.

The issue of mental illness in the United States has become a growing and omnipresent problem. Las Vegas is no different than many of these cities. Thus one weakness is the current emphasis with planning departments, public officials, and healthcare providers to address symptoms and not the disease. Homelessness is a symptom many cities experience. Mental illness is the causation for many who are homeless. Suicide, addiction, and aging in isolation are all symptoms of a growing mental health concern. Lack of green spaces, places of impromptu social gathering, and active transportation are all included into the purview of urban design, which thus provides many opportunities to address the growing mental health concern.