|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2018:5;4

|

An analysis of high-rise living in terms of provision of appropriate social spaces for children

Suruchi Modi

Associate Professor, Sushant School of Art and Architecture, Ansal University, India

Associate Professor, Sushant School of Art and Architecture, Ansal University, India

Introduction

The significance of the skyscraper typology persists as populations grow, land continues to become scarce, and to defy the detrimental social and environmental effects of urban sprawl. What this typology seems to have denied over many years is its relationship with the child. It has led to a rapid decline of children’s physical activity and independent mobility resulting in increased rates of child obesity and other health concerns as described by psychologists and medical professionals across the country. The question which does not seem to be answered is: Are high rises a good environment for nurturing children? However, looking at the unprecedented growth of residential tall buildings there might be very little room left in the cities of tomorrow in order to address and provide for good living opportunities for children if the typologies of today deny it. This paper is an investigation of the use of designed social spaces by children in the housing typologies of Delhi National Capital Region (NCR). It aims to bring forth the analysis of these spaces the in order to make high rises desirable for raising families with children.

Effects of high-rise living on families

The residential typology has transformed from that of a detached and semi-detached bungalow to units stacked one above the other to form a tower. These tower blocks have drawn many criticisms from sociologists, architects and urban designers as a symbol of social problems such as isolation and exclusion. Being located on the periphery of the city, residents felt secluded from society. Crime, theft and vandalism became common, assisted by concealed areas, dark and dingy corridors and other badly designed corners within tower blocks. Such apparent failures have led to major debates about their increasing unpopularity amongst users.

Figure 1.1 : Red Road Flats, Glasgow [Source : Burrell, 2010]; Figure 1.2 : Crossway Estate, London [Source : Crossways, 2007]

Oscar Newman claimed in his book ‘Defensible Space’ that ‘there is a distinct correlation between crime and the type of urban dwelling, and that physical environment directly influences human behaviour and encourages certain types of activities to take place’, (Newman, 1972). In her book Utopia on Trial, Alice Coleman investigated about 4000 residential blocks in the peripheral settlements of London and brought forward the relationship between high-rise design and anti-social behaviour, or as she calls it “social malaise” (Coleman,1985). Madam Gregoire accused architects and planners ‘who seem to build for families without realising that they often include children' (Gregoire, 1971).

The main criticism mothers raise concerns the poor accessibility and visibility of play areas in high rises: existing play areas often are not used due to the mothers' need to have their children in their visual vicinity. Children tend to be greatly influenced by this restriction, having fewer friends and restricted freedom, which may be associated with less-well developed social and motor skills that would otherwise develop through recreation and play.

Additionally the association between multi-storey housing and physical and mental health, has long been recognized as a factor which is believed to make residents vulnerable to certain types of illness. Goodman, in his study states ‘there was a high prevalence of physical and mental illness, much due to the physical factors associated with the estate’, (Goodman, 1966). He found that respiratory problems, especially among children, occurred more often in the flats, while psychoneurotic disorders in women showed a similar pattern.

As a result of such findings, high-rise living underwent many adaptations in order to accommodate functions and spaces for a better social life of its residents. Architects such as Le Corbusier, Moshe Safdie, Smithsons, Arata Isozaki amongst others tried and tested variations of the high-rise typology with both successes and failures to learn from.

The main criticism mothers raise concerns the poor accessibility and visibility of play areas in high rises: existing play areas often are not used due to the mothers' need to have their children in their visual vicinity. Children tend to be greatly influenced by this restriction, having fewer friends and restricted freedom, which may be associated with less-well developed social and motor skills that would otherwise develop through recreation and play.

Additionally the association between multi-storey housing and physical and mental health, has long been recognized as a factor which is believed to make residents vulnerable to certain types of illness. Goodman, in his study states ‘there was a high prevalence of physical and mental illness, much due to the physical factors associated with the estate’, (Goodman, 1966). He found that respiratory problems, especially among children, occurred more often in the flats, while psychoneurotic disorders in women showed a similar pattern.

As a result of such findings, high-rise living underwent many adaptations in order to accommodate functions and spaces for a better social life of its residents. Architects such as Le Corbusier, Moshe Safdie, Smithsons, Arata Isozaki amongst others tried and tested variations of the high-rise typology with both successes and failures to learn from.

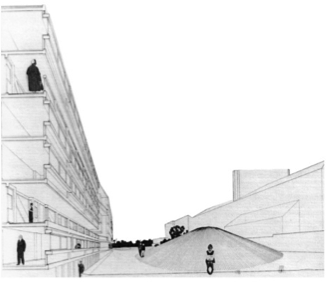

Figure 2.1 : United Habitation [Source : Irwin, 2009]; Figure 2.2 : Habitat 67, Montreal [Source : Nasab, 2010]; Figure 2.3 : Robin Hood Gardens [Source : Smithson, 1970]

Social spaces for children

Social sustainability is defined as a ‘development that is compatible with the harmonious evolution of civil society, fostering an environment favourable to the compatible cohabitation of culturally and socially diverse groups while at the same time encouraging social integration, with improvement in the quality of life for all segments of the population’, (Polese & Stren, 2000). However, the physical aspects of social sustainability are not addressed much in the realm of the built environment by planners, urban designers and architects.

Interest in ‘child-friendly communities’ has grown recently, mainly because of the recognition by medical professionals of the importance of children being outdoors for unsupervised play and physical activity. The presence of open spaces in the built environment plays a key role in children’s well-being, whether experienced in the immediate residential environment, in play settings or simply by viewing it through windows. Children benefit from opportunities to roam free and play outside without interference from adults, a behaviour that can be facilitated by good neighbourhood design.

According to Javdekar et al (2015)'s case studies in urban India, ‘Children from middle-class families are usually susceptible to the pressures of expected educational achievement, increasing access to digital technology and structured leisure time, which can all impede the fulfilment of their right to play’. The resulting problems range from fundamental child development issues to everyday activities such as access to play (Oke, Khattar, Pant & Saraswathi, 1999). Children whose lives are too controlled may not have the chance to learn certain key life skills that are best acquired through self-directed experiences, and may find it increasingly difficult to cope with them as they grow up. It is seen that children associate with a space according to the affordances it offers. ‘As children find affordances in an environment, they perceive that environment as an interesting and challenging place of adventure and exploration that inspires them to move around and find even more affordances’, (Gibson, 1994). Thus the benefits of outdoor play laid by him and others like Robin Moore include:

Interest in ‘child-friendly communities’ has grown recently, mainly because of the recognition by medical professionals of the importance of children being outdoors for unsupervised play and physical activity. The presence of open spaces in the built environment plays a key role in children’s well-being, whether experienced in the immediate residential environment, in play settings or simply by viewing it through windows. Children benefit from opportunities to roam free and play outside without interference from adults, a behaviour that can be facilitated by good neighbourhood design.

According to Javdekar et al (2015)'s case studies in urban India, ‘Children from middle-class families are usually susceptible to the pressures of expected educational achievement, increasing access to digital technology and structured leisure time, which can all impede the fulfilment of their right to play’. The resulting problems range from fundamental child development issues to everyday activities such as access to play (Oke, Khattar, Pant & Saraswathi, 1999). Children whose lives are too controlled may not have the chance to learn certain key life skills that are best acquired through self-directed experiences, and may find it increasingly difficult to cope with them as they grow up. It is seen that children associate with a space according to the affordances it offers. ‘As children find affordances in an environment, they perceive that environment as an interesting and challenging place of adventure and exploration that inspires them to move around and find even more affordances’, (Gibson, 1994). Thus the benefits of outdoor play laid by him and others like Robin Moore include:

- Integrates informal play and formal learning

- Builds cognitive constructs

- Stimulates imagination and creativity

- Creates understanding through primary experience

- Provides microclimatic comfort

- Enables children to:

- Find their own self-identified and self-guided interests

- Make decisions, solve problems, exert self-control and follow rules

- Handle emotions like anger and fear

- Make friends and learn to get along with each other as peers

Tower Blocks Re-visioned : The case of Delhi NC

Today, Delhi faces the maximum migration in the context of India. The high rise housing typology in the city has witnessed various forms of criticisms and refinement and has also seen many players, including institutional, co-operative, government and private developers. Its NCR region has witnessed high-rise development that have changed the face of living in tall buildings in India. Today there exist numerous replications of these faces in other cities and the trend is having a large impact on the future proposals of high rise development in the country.

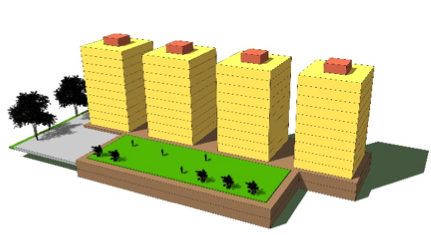

Evidence has shown that living in high rises hinders the possibilities for the spontaneous play and exploration that young children thrive on. According to Goleman (1987): ‘The high-rise apartment can present hurdles to a toddler's psychological growth, particularly to the young child's need to develop a sense of autonomy’. A pair of metaphors, the “Tower in the Park” and the “Building as a Street” came as solutions in the case of Delhi NCR, and the period between 1990’s to 2010 saw high rises modelled on these concepts. Co-operative housing associations were open to experiment with newer ideas and hence many projects like Technology Apartments, Pooja Apartments, Sanskriti Apartments etc with corridors connecting the units on alternate floors replicating streets in a neighbourhood were seen. Another approach to provide social spaces in tall building was in the form of terraces which mainly aimed to fulfil the fire codes for buildings higher than 8 floors. Though these terraces were provided to appease the fire codes, their use as social spaces by the residents opened another form of shared spaces in tall places.

The 1990s also saw a rise of private developers. Since they were not allowed to operate within the city limits, they bought agricultural land along the periphery of Delhi and thus, NCR came into formation. The rising aspirations of the middle income families who didn’t want to live in government-designed apartment buildings and who could not afford independent bungalows resulted in out-migration from the increasingly crowded heart of the city to more spacious surroundings like the NCR where land was cheaper. Here, large scale developments in the form of self-sufficient gated housing were created, providing larger shared open spaces and other amenities for children. This form of housing soon became a standard way of living for the city to such an extent that today it is the prototype most commonly designed for low-income and vulnerable people. However, such neighbourhoods are rising above 20 floors with a fabric of closely knit buildings over small pieces of land in order to accommodate higher densities and to bring down the cost of apartments. Although these experiments provide affordable units with amenities and open spaces, whether on ground or as streets and terraces, the question that still arises is: to what extent are these spaces actually useful to children?

Evidence has shown that living in high rises hinders the possibilities for the spontaneous play and exploration that young children thrive on. According to Goleman (1987): ‘The high-rise apartment can present hurdles to a toddler's psychological growth, particularly to the young child's need to develop a sense of autonomy’. A pair of metaphors, the “Tower in the Park” and the “Building as a Street” came as solutions in the case of Delhi NCR, and the period between 1990’s to 2010 saw high rises modelled on these concepts. Co-operative housing associations were open to experiment with newer ideas and hence many projects like Technology Apartments, Pooja Apartments, Sanskriti Apartments etc with corridors connecting the units on alternate floors replicating streets in a neighbourhood were seen. Another approach to provide social spaces in tall building was in the form of terraces which mainly aimed to fulfil the fire codes for buildings higher than 8 floors. Though these terraces were provided to appease the fire codes, their use as social spaces by the residents opened another form of shared spaces in tall places.

The 1990s also saw a rise of private developers. Since they were not allowed to operate within the city limits, they bought agricultural land along the periphery of Delhi and thus, NCR came into formation. The rising aspirations of the middle income families who didn’t want to live in government-designed apartment buildings and who could not afford independent bungalows resulted in out-migration from the increasingly crowded heart of the city to more spacious surroundings like the NCR where land was cheaper. Here, large scale developments in the form of self-sufficient gated housing were created, providing larger shared open spaces and other amenities for children. This form of housing soon became a standard way of living for the city to such an extent that today it is the prototype most commonly designed for low-income and vulnerable people. However, such neighbourhoods are rising above 20 floors with a fabric of closely knit buildings over small pieces of land in order to accommodate higher densities and to bring down the cost of apartments. Although these experiments provide affordable units with amenities and open spaces, whether on ground or as streets and terraces, the question that still arises is: to what extent are these spaces actually useful to children?

Figure 3.1 : Saraswati Narmada Ganga Yamuna Apartments, New Delhi [Source : Author, 2017]; Figure 3.2 : Tulip Orange, Gurgaon [Source : Author, 2017]; Figure 3.3 : Panchsheel Wellington, Ghaziabad [Source : Author, 2017]

Figure 3.4 : Technology Apartments [Source : Author, 2017]; Figure 3.5 : Sanskriti Apartments [Source : Author, 2018]; Figure 3.6 : Navkunj Apartments [Source : Author, 2017]

Method

This paper is a study that closely examines two types of (horizontally- and vertically-placed) distribution of spaces in high rise living prevalent in the city of Delhi and brings forth the learnings from them. Surveys were performed by means of questionnaires, semi structured interviews and group discussions. Being a child-centric research and with literature concluding that parents govern and structure most of the child’s time, it became important to garner parental perceptions of their local environments. This helped to provide a viewpoint for their child and their concerns with social spaces in the neighbourhood. The child respondents were categorized as per the age groups as laid down by Robin Moore. The research focused on three categories (elementary years 3 to 7, middle childhood years 8 to 11, Pre adolescence years 12 to 14) as these happen to be the crucial years that shape later life.

Semi structured questionnaires were targeted for the RWA (Residents Welfare Association) of each neighbourhood, and for their children. Cases for field work were chosen based on the analysis of the formal housing of Delhi and the Pilot Studies undertaken. They were categorized in to two types of residential high rises:

The survey took nearly fifty days for completion over the six chosen cases. The target was to cover 70% of the parents in each neighborhood but due to their unavailability and unwillingness to participate nearly 40% to 50% resident surveys were conducted with only one parent’s participation. These people ranged from ones residing in the neighborhood from a minimum period of 2 years to more than 30 years. The children in the middle childhood and pre adolescence years which participated with much zeal, reaching 60%. The participation in the elementary year category was much lower and also not very beneficial as most of it was controlled by the accompanying adults.

Semi structured questionnaires were targeted for the RWA (Residents Welfare Association) of each neighbourhood, and for their children. Cases for field work were chosen based on the analysis of the formal housing of Delhi and the Pilot Studies undertaken. They were categorized in to two types of residential high rises:

- Vertical Cases : Where the units are connected to the social spaces on ground by elevators only. Thus there is only a vertical movement system at height. Namely and Tulip Orange, Gurgaon; Panchsheel Wellington, Crossing Republic, Ghaziabad and Saraswati Narmada Ganga Yamuna Apartments, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi

- Horizontal Cases : Where the Units are connect by streets and terraces which are the horizontal movement systems at height along with the elevators. These were Sanskriti Apartments, Dwarka; Technology Apartments and Navkunj Apartments, I.P. Extension, New Delhi.

The survey took nearly fifty days for completion over the six chosen cases. The target was to cover 70% of the parents in each neighborhood but due to their unavailability and unwillingness to participate nearly 40% to 50% resident surveys were conducted with only one parent’s participation. These people ranged from ones residing in the neighborhood from a minimum period of 2 years to more than 30 years. The children in the middle childhood and pre adolescence years which participated with much zeal, reaching 60%. The participation in the elementary year category was much lower and also not very beneficial as most of it was controlled by the accompanying adults.

Results and Analysis

Diversity

Nearly 70% of the people had lived in a bungalow/builder floor or an apartment with lesser amenities before moving into these neighbourhoods. In the horizontal cases, where more units were connected on the same floor by streets or terraces, nearly 50% of children's friends lived on the same floor, whereas in the vertical cases this proportion was reduced to 15%. Eighty percent of children in the horizontal cases were able to meet their friends on a daily basis, versus the vertical case where only 45% of children were able to meet their friends daily.

Social spaces @ height

In the vertical cases nearly half of children were found to be playing within their units due to lack of common spaces on the same floor. In the horizontal cases, this proportion was only 8%, while 45% of children were found engaging with each other on the same floor. However, playing collective games on the streets and terraces at height was found to be difficult due to the proportions of the space.

In the vertical cases 80% of parents supported the need to have social spaces at height near their units. In the horizontal cases parents appreciated the provision of social spaces at height though 45% of them were not happy with its placement. The streets being located in the form of corridors all along the length of the units became a cause of everyday disturbance due to noise and also resulted in a loss of privacy.

Social spaces @ ground

In the vertical cases, large sized parks allowed for multiple activities for children including ball games, events etc., but the parks and other social spaces were not located centrally within the neighbourhood. These social spaces were also not visually connected with most of the units.

In the horizontal cases, due to the small sized neighbourhoods, the centrally located social spaces were too small to allow for ball games for elder children. The limited scale restricted children from many play activities and opportunities. However, in terms of visibility, 80% of parents were able to view these spaces from their units or from the streets and terraces on their floor.

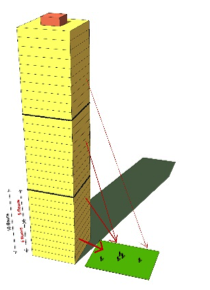

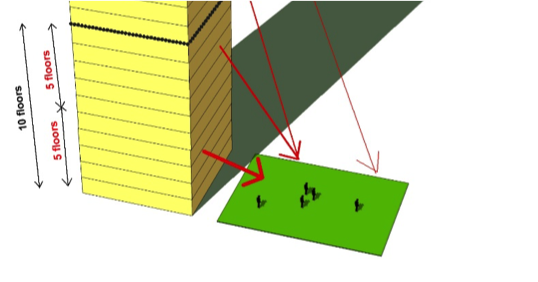

Factor of height

Tests were conducted on the sites to establish the physical limits of verbal and visual communication. Parents were asked to spot the child’s activity on the ground floor and to visually and verbally communicate with them from their respective floor or unit. Results of these tests revealed that on the ground, first, second and third floors, most of the parents could clearly see the activity the child was performing on the ground and could verbally communicate with them. On the fourth and fifth floors, parents could see their child but were not able to clearly judge the activity they were engaged in and had difficulty communicating verbally with the children. From the sixth to the ninth floor, parents could see the child but could not identify the activity the child was involved in, and had increased difficultly communicating verbally with them.

Security

Non-gated neighbourhoods and areas without a good security system were the primary concern for parents sending their children down to play. In case of smaller neighbourhoods, where the community bonding was strong with everybody knowing each other, security was not a big concern and parents were comfortable sending children to play, even with the absence of CCTV surveillance. Other factors of security included light and ventilation. The terraces and streets in the horizontal cases were open spaces and received natural light. The vertical cases with enclosed lift lobbies and corridors had dark and dingy zones prone to anti-social activities.

Safety

Where there was a clear segregation of vehicular and pedestrian movement like in Panchsheel Wellington and Navkunj apartments, children found it safe to run, cycle and skate. At Sanskriti apartments and Tulip Orange where there was interference between the two, it was observed that nearly 65% parents did not send their children alone. Also in the horizontal cases, the edge conditions of the streets and terraces were found to be prone to accidents and fall hence parents did not prefer to send or leave their children independently to play in these spaces.

Travel to social spaces

In the vertical cases, 50% of boys and 80% of girls were not allowed to travel to play unaccompanied by an adult. The prime reasons for this were disorientation, the risk of one’s way around, and of falling prey to anti-social activities. On the other hand, in the horizontal cases, 60% children were allowed to move around unaccompanied, irrespective of gender. This was possible because the neighbourhood scale was small with everyone known, and the requisite security system was in place.

Playtime and participation

70% to 80% of children in the vertical cases played for less than an hour as an average. The factor of adults having to accompany them to play areas restricted children's play time during weekdays. Playing time increased by an hour on the weekends as adults had more time. In case of horizontal cases, the play time of children spanned between one to two hours on weekdays and weekends. The other factor affecting play time of children was the protection of these social spaces from harsh weather conditions. Most of these spaces were open to sky without any intended or designed covering, making the social spaces unusable during parts of the day and year. Also affected was their participation in community events: the children who could not regularly formulate local social groups were less eager to be involved in neighborhood-level occasions and activities. Also fewer events were seen to be organized by residents of those neighborhoods.

Nearly 70% of the people had lived in a bungalow/builder floor or an apartment with lesser amenities before moving into these neighbourhoods. In the horizontal cases, where more units were connected on the same floor by streets or terraces, nearly 50% of children's friends lived on the same floor, whereas in the vertical cases this proportion was reduced to 15%. Eighty percent of children in the horizontal cases were able to meet their friends on a daily basis, versus the vertical case where only 45% of children were able to meet their friends daily.

Social spaces @ height

In the vertical cases nearly half of children were found to be playing within their units due to lack of common spaces on the same floor. In the horizontal cases, this proportion was only 8%, while 45% of children were found engaging with each other on the same floor. However, playing collective games on the streets and terraces at height was found to be difficult due to the proportions of the space.

In the vertical cases 80% of parents supported the need to have social spaces at height near their units. In the horizontal cases parents appreciated the provision of social spaces at height though 45% of them were not happy with its placement. The streets being located in the form of corridors all along the length of the units became a cause of everyday disturbance due to noise and also resulted in a loss of privacy.

Social spaces @ ground

In the vertical cases, large sized parks allowed for multiple activities for children including ball games, events etc., but the parks and other social spaces were not located centrally within the neighbourhood. These social spaces were also not visually connected with most of the units.

In the horizontal cases, due to the small sized neighbourhoods, the centrally located social spaces were too small to allow for ball games for elder children. The limited scale restricted children from many play activities and opportunities. However, in terms of visibility, 80% of parents were able to view these spaces from their units or from the streets and terraces on their floor.

Factor of height

Tests were conducted on the sites to establish the physical limits of verbal and visual communication. Parents were asked to spot the child’s activity on the ground floor and to visually and verbally communicate with them from their respective floor or unit. Results of these tests revealed that on the ground, first, second and third floors, most of the parents could clearly see the activity the child was performing on the ground and could verbally communicate with them. On the fourth and fifth floors, parents could see their child but were not able to clearly judge the activity they were engaged in and had difficulty communicating verbally with the children. From the sixth to the ninth floor, parents could see the child but could not identify the activity the child was involved in, and had increased difficultly communicating verbally with them.

Security

Non-gated neighbourhoods and areas without a good security system were the primary concern for parents sending their children down to play. In case of smaller neighbourhoods, where the community bonding was strong with everybody knowing each other, security was not a big concern and parents were comfortable sending children to play, even with the absence of CCTV surveillance. Other factors of security included light and ventilation. The terraces and streets in the horizontal cases were open spaces and received natural light. The vertical cases with enclosed lift lobbies and corridors had dark and dingy zones prone to anti-social activities.

Safety

Where there was a clear segregation of vehicular and pedestrian movement like in Panchsheel Wellington and Navkunj apartments, children found it safe to run, cycle and skate. At Sanskriti apartments and Tulip Orange where there was interference between the two, it was observed that nearly 65% parents did not send their children alone. Also in the horizontal cases, the edge conditions of the streets and terraces were found to be prone to accidents and fall hence parents did not prefer to send or leave their children independently to play in these spaces.

Travel to social spaces

In the vertical cases, 50% of boys and 80% of girls were not allowed to travel to play unaccompanied by an adult. The prime reasons for this were disorientation, the risk of one’s way around, and of falling prey to anti-social activities. On the other hand, in the horizontal cases, 60% children were allowed to move around unaccompanied, irrespective of gender. This was possible because the neighbourhood scale was small with everyone known, and the requisite security system was in place.

Playtime and participation

70% to 80% of children in the vertical cases played for less than an hour as an average. The factor of adults having to accompany them to play areas restricted children's play time during weekdays. Playing time increased by an hour on the weekends as adults had more time. In case of horizontal cases, the play time of children spanned between one to two hours on weekdays and weekends. The other factor affecting play time of children was the protection of these social spaces from harsh weather conditions. Most of these spaces were open to sky without any intended or designed covering, making the social spaces unusable during parts of the day and year. Also affected was their participation in community events: the children who could not regularly formulate local social groups were less eager to be involved in neighborhood-level occasions and activities. Also fewer events were seen to be organized by residents of those neighborhoods.

Conclusion

As a result of moving into these high-rise typologies, more and more children of middle class families are broken away from the joint family systems that support them. Findings in this research support the concern that that restricted child-friendly environment in these high-rise typologies can result in isolated lifestyles. Evidence has shown that isolation and lack of spontaneous social play can have adverse effects on children’s development, mental health and well-being. Opportunities for improvements exist. There is a growing awareness amongst real estate professionals that high rise living needs to provide not only shelter but also promote mental health and aid social interaction. By analysing and proposing solutions, this paper concludes with the following strategic points to provide children (and their families) with improved social interaction, more play, and better mental health and well-being.

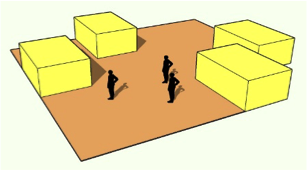

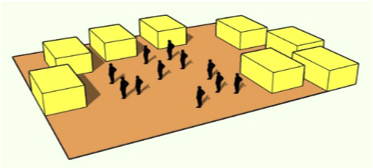

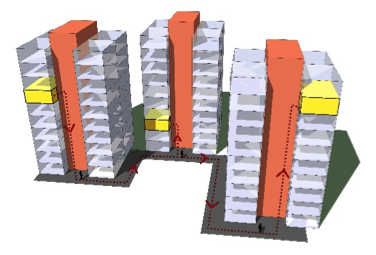

1. Number of units on a floor need to be proportional to the opportunities children have of making friends on their floor.

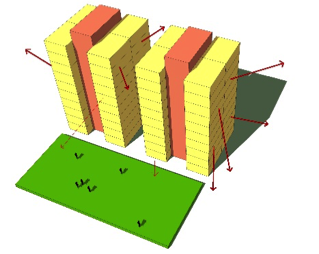

Figure 4 : Number of units proportional to the potential friends per floor [Source: Author]

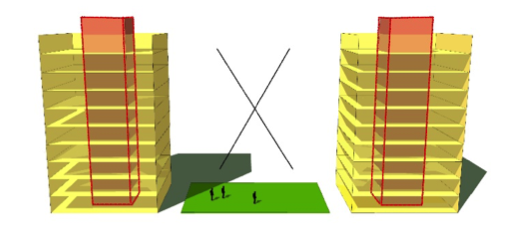

2. Social Spaces need to be visually connected to each other and from the home unit to allow children to play for longer time frames.

Figure 5: Social spaces visually connected from the units and lobbies [Source: Author]

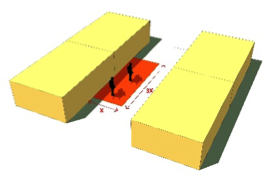

3. Social spaces at height can become desirable and active places if the factors of proportion, edge conditions and environmental comfort are accounted for and designed strategically. Issues of noise and loss of privacy for the residents must also be addressed.

Figure 6: Proportions of social spaces at height and design of edge conditions [Source: Author]

4. Restrictions created by small size and number of open spaces can be overcome by providing space allocations for elder children to play larger ball games.

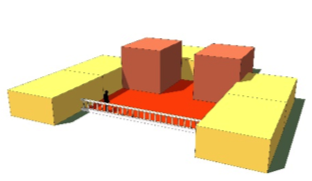

5. The study establishes the tenth floor as a benchmark beyond which visual and verbal communication gets lost. However, the fifth floor can be considered as a desirable level for providing social spaces along the height of a building for ease of communication.

Figure 7: Benchmark Floors for providing Social Spaces along height of the building [Source: Author]

6. Develop buildings that provide diversity and good security systems, and limit vehicular access to reduce hindrances to play. Independent mobility of children can be affected by: similar looking buildings, security systems, areas prone to anti-social activities, and the fear of encountering a speeding vehicle. The distance of social spaces from the units is inversely proportional to the time the children can spend playing.

Figure 8: Similar looking disjointed buildings [Source: Author]; Figure 4.6 : Lack of environmental comfort in social spaces [Source : Author]

7. Provide smaller neighborhoods: Smaller sized neighbourhoods (i.e. of a capacity of 200 to 300 units per hectare) are more secure for children as most people are familiar to each another.

8. Provide outdoor opportunities: Where more time is spent outdoors, stronger bonds can be created, more people are known and hence there is more active participation seen from children.

9. On Ground: The survey establishes location, light and ventilation, area and proportion and environmental comfort as areas of concern for social spaces on ground.

10. At Height: For social spaces at height the prime concerns are location, security, street furniture, safety, aesthetics and area and proportion of the space.

The analysis of the cases in this paper demonstrate the potential to actively promote the mental health and well-being of children by providing built environments that support an array of social spaces in high-rise neighbourhoods. This paper has found that location for easy access by both children and parents, a secure neighbourhood with spaces that are safe in design, and climatically comfortable spaces are the prime attributes of a successful social space for children. High-rise neighbourhoods that support such layouts in consideration of children’s needs for play and social activity can help build happy lives for children and their families.

8. Provide outdoor opportunities: Where more time is spent outdoors, stronger bonds can be created, more people are known and hence there is more active participation seen from children.

9. On Ground: The survey establishes location, light and ventilation, area and proportion and environmental comfort as areas of concern for social spaces on ground.

10. At Height: For social spaces at height the prime concerns are location, security, street furniture, safety, aesthetics and area and proportion of the space.

The analysis of the cases in this paper demonstrate the potential to actively promote the mental health and well-being of children by providing built environments that support an array of social spaces in high-rise neighbourhoods. This paper has found that location for easy access by both children and parents, a secure neighbourhood with spaces that are safe in design, and climatically comfortable spaces are the prime attributes of a successful social space for children. High-rise neighbourhoods that support such layouts in consideration of children’s needs for play and social activity can help build happy lives for children and their families.

References

Baldick, R. (1962). Centuries of Childhood : A social History of Family Life. Jonathan Cape Ltd.

Coleman A. (1985), Utopia on Trial : Vision and reality in planned housing, Hilary Shipman Ltd., London

Conway J.D. (1977), Human response to tall buildings, Hutchinson & Ross Inc., Pennsylvania

Delhi Development Authority (2007). The Delhi Master Plan 2021. Rupa and Co. New Delhi

Ganju, A. (2011). Lost in Transformation. [Online] Available at : https://unsettledcity.wordpress.com/tag/ashish-ganju/ [Accessed on 3rd Nov 2016]

Gehl J. (1971), Life Between Buildings : Using Public Space, Island Press, Washington

Gibson, J.J. (1977). "The Theory of Affordances", in Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. p. 127-143

Goleman D. (1987), A high rise is not a home for children, New York Times Archives. [Online] Available at : https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/10/garden/a-high-rise-is-not-a-home-for-children-the-experts-say.html [ Accessed on 14th March 2017]

Goodman P. & Goodman P. (1966), Communitas : Means of livelihood and ways of life, Vintage Books, NY

Jain A.K. (1990). The Making of a Metropolis : Planning and Growth of Delhi. National Book Trust

Javdekar, S.A. ; Wridt, P. & Hart, R. (2015). Spatializing Children's Rights: A Comparison of Two Case Studies from Urban India. Child friendly Cities. Volume 25, No. 02

Jephcott P. & Robinson H. (1971), Homes in High Flats : some of the human problems involved in multi-storey housing, University of Glasgow Social and Economic Studies, Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh

Lee T. (2004), The living skyscraper : Mapping the vertical neighbourhood, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Library

Moore, R. (1997). The need for nature : a Childhood Right . In Social Justice [Online] Volume 24. Available at https://naturalearning.org/need-nature-childhood-right [Accessed on 21 Jul. 2016]

Polèse, Mario, And Richard Stren. (2000), Understanding the New Sociocultural Dynamics of Cities: Comparative Urban Policy in a Global Context, (Ed. POLÈSE M. & STREN R.), University of Toronto Press

Menon, A.G.K. (2003). The Contemporary Architecture of Delhi : A Critical History. TVB School of Habitat Studies. New Delhi

Mukherjee, A. (1993). Explorations into Group Housing in Delhi. Unpublished Architectural Dissertation. School of Planning and Architecture. New Delhi

Vaastu Shilp Foundation (1988). Residential Open Spaces : A Behavioural Analysis. Report. Ahmedabad.

Coleman A. (1985), Utopia on Trial : Vision and reality in planned housing, Hilary Shipman Ltd., London

Conway J.D. (1977), Human response to tall buildings, Hutchinson & Ross Inc., Pennsylvania

Delhi Development Authority (2007). The Delhi Master Plan 2021. Rupa and Co. New Delhi

Ganju, A. (2011). Lost in Transformation. [Online] Available at : https://unsettledcity.wordpress.com/tag/ashish-ganju/ [Accessed on 3rd Nov 2016]

Gehl J. (1971), Life Between Buildings : Using Public Space, Island Press, Washington

Gibson, J.J. (1977). "The Theory of Affordances", in Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. p. 127-143

Goleman D. (1987), A high rise is not a home for children, New York Times Archives. [Online] Available at : https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/10/garden/a-high-rise-is-not-a-home-for-children-the-experts-say.html [ Accessed on 14th March 2017]

Goodman P. & Goodman P. (1966), Communitas : Means of livelihood and ways of life, Vintage Books, NY

Jain A.K. (1990). The Making of a Metropolis : Planning and Growth of Delhi. National Book Trust

Javdekar, S.A. ; Wridt, P. & Hart, R. (2015). Spatializing Children's Rights: A Comparison of Two Case Studies from Urban India. Child friendly Cities. Volume 25, No. 02

Jephcott P. & Robinson H. (1971), Homes in High Flats : some of the human problems involved in multi-storey housing, University of Glasgow Social and Economic Studies, Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh

Lee T. (2004), The living skyscraper : Mapping the vertical neighbourhood, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Library

Moore, R. (1997). The need for nature : a Childhood Right . In Social Justice [Online] Volume 24. Available at https://naturalearning.org/need-nature-childhood-right [Accessed on 21 Jul. 2016]

Polèse, Mario, And Richard Stren. (2000), Understanding the New Sociocultural Dynamics of Cities: Comparative Urban Policy in a Global Context, (Ed. POLÈSE M. & STREN R.), University of Toronto Press

Menon, A.G.K. (2003). The Contemporary Architecture of Delhi : A Critical History. TVB School of Habitat Studies. New Delhi

Mukherjee, A. (1993). Explorations into Group Housing in Delhi. Unpublished Architectural Dissertation. School of Planning and Architecture. New Delhi

Vaastu Shilp Foundation (1988). Residential Open Spaces : A Behavioural Analysis. Report. Ahmedabad.

About the Authors

|

Suruchi Modi is an architect and urban designer with a specialisation in Tall Building Design from the University of Nottingham UK. She is an Associate Professor and Programme Head for the Masters programmes in architecture at Sushant School of Art and Architecture, Ansal University Gurgaon and is currently pursuing a PhD at the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi. She was awarded for her project : Revival of mixed land use concept as a tool to develop a sustainable city model at Cept University and is also an international award winner of the Passivehaus skyscraper design for New York City. She has worked on large-scale master planning and urban revitalization projects, and has been actively involved in academia and research for over 17 years. Her work aims to extend the realm of sustainability to the real estate-driven high-rise development of our cities today, bringing forth more appropriate concepts & technologies for tall buildings.

|