|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health; 2018:5;3

|

From infrastructure to playground: the playable soul of Copenhagen

Alice Covatta

Visiting Researcher in Architecture and Urban Design at Keio University, Tokyo, Japan

Visiting Researcher in Architecture and Urban Design at Keio University, Tokyo, Japan

Introduction

Play moves between different realms and definitions, reality and unreality, space and time, collective and individual, freedom and rules. (1) In 1997 the ambiguous character of play becomes the title of one of the most comprehensive studies on the topic, The Ambiguity of Play by Sutton-Smith. The author himself has manifested the difficulties to define what play is, though every reader has a clear feeling of what playing provokes. One trait that the book highlights the character between freedom expressed by Johan Huizinga “Here, then, we have the first main characteristic of play: that it is free, is in fact freedom. A second characteristic is closely connected with this, namely, that play is not "ordinary" or "real" life. It is rather a stepping out of "real" life into a temporary sphere of activity with a disposition all of its own” (2) and restriction expressed by Roger Caillois “The game must be taken back within the agreed boundaries. The same is true for time: the game starts and ends at given signal”. (3)

Play is defined both spatially and temporally: “Play is distinct from "ordinary" life both as to locality and duration” (4), and when translated into our cityscape it can be a powerful tool able to transform anonymous urban setting into "extraordinary" space where the activities, movements and uses are carried on by the player because he/she likes doing it, freely accepting the play limitation.

Playgrounds spread in our urban environment are the setting for playful activities such as fun, relaxation, exercise or escape becoming a qualitative manifestation for a healthy human experience. Inside the playground border, the rules of the game hold, but at the same time the free nature of play when is affected by the non-optimal urban/social conditions of the context can easily assume a fragile status and disappear.

Therefore, both the protection and the promotion of playful spaces need careful attention, especially in the contemporary urban settlement. Hence, the aim of this paper is firstly to add nuance to the understanding of urban design linked to playful activities in order to improve mental health conditions especially in children and teenagers. Secondly, it aims to give practical examples through a case study analysis of how urban planning and urban design can affect positively play creating new opportunities.

Play is defined both spatially and temporally: “Play is distinct from "ordinary" life both as to locality and duration” (4), and when translated into our cityscape it can be a powerful tool able to transform anonymous urban setting into "extraordinary" space where the activities, movements and uses are carried on by the player because he/she likes doing it, freely accepting the play limitation.

Playgrounds spread in our urban environment are the setting for playful activities such as fun, relaxation, exercise or escape becoming a qualitative manifestation for a healthy human experience. Inside the playground border, the rules of the game hold, but at the same time the free nature of play when is affected by the non-optimal urban/social conditions of the context can easily assume a fragile status and disappear.

Therefore, both the protection and the promotion of playful spaces need careful attention, especially in the contemporary urban settlement. Hence, the aim of this paper is firstly to add nuance to the understanding of urban design linked to playful activities in order to improve mental health conditions especially in children and teenagers. Secondly, it aims to give practical examples through a case study analysis of how urban planning and urban design can affect positively play creating new opportunities.

Play and mental health in childhood and adolescence

There has been debate about the extent to which there is an association between play and mental health. During the last decades, an increasing number of research papers have confirmed their reciprocal association; play can improve mental health conditions in people with depression and other mental disorders and viceversa: the lack of play during childhood is a a contributing factor to mental health problems in children and adolescents. (5)

The main supporter of the relation between play and mental health is the American psychologist Peter Gray. He argues that there is a linear connection between the decrease of play with the rise of psychopathology. In his research, he first documents the decrease of play as a social activitie, with a focus on children who live in developing nations. Over the past fifty years, more and more children have had limited opportunities to play outdoor activities with other playmates; instead they have been engaged with more solitary indoor activities such as computer games or watching television, although “playing outside at a playground or park” has been always ranked among the activities that made children happiest. (6)

The main supporter of the relation between play and mental health is the American psychologist Peter Gray. He argues that there is a linear connection between the decrease of play with the rise of psychopathology. In his research, he first documents the decrease of play as a social activitie, with a focus on children who live in developing nations. Over the past fifty years, more and more children have had limited opportunities to play outdoor activities with other playmates; instead they have been engaged with more solitary indoor activities such as computer games or watching television, although “playing outside at a playground or park” has been always ranked among the activities that made children happiest. (6)

Figure 1: Kids playing football under tree shadows, Central Park NY, photo Alice Covatta, 2016

There are multiple factors that account for the shift from outdoor-social play to indoor-solitary play, but mainly is a parent's decision against the public space. In fact in the survey presented by Gray, the main reasons for the decrease of outdoor social activities were identified as the mother's fear of crime and the lack of security in the available public space. Another reason was that young people's limited free time available after school was often spent doing schoolwork or doing shopping with parents.

At the same time, Gray highlights the increase in mental health problems experienced by young people: anxiety, depression, feelings of helplessness and narcissism have increased over the same period. In Gray's words: "I argue that without play, young people fail to acquire the social and emotional skills necessary for healthy psychological development."(7) Gray considers that there are five factors that account for how play acts as a protective factor for young people's mental health:

At the same time, Gray highlights the increase in mental health problems experienced by young people: anxiety, depression, feelings of helplessness and narcissism have increased over the same period. In Gray's words: "I argue that without play, young people fail to acquire the social and emotional skills necessary for healthy psychological development."(7) Gray considers that there are five factors that account for how play acts as a protective factor for young people's mental health:

- Develop intrinsic interest and competences

- Learn how to make decisions, solve problems, exert self-control, and follow rules - during games, children must make decisions about what to do and how to do it, eventually to solve problems and to respect game's rules to keep it going on. In adult life, this translates to an ability to make decisions, accept rules, and to achieve self-control over fear or anger.

- Learn how to regulate their emotion

- Make friends and learn to get along with others as equals

- Experience joy

Figure 2. Collage “Tokyo Playground”, Alice Covatta, 2017

How urban living can affect play

As Gray highlights, two main drivers of the decline of play are the parent's fear of public spaces, imagined as a setting for crime, and also the general decrease of accessible spaces available for playful activities. Therefore, to take action in the urban environment is a priority on one hand to understand the causes of the decline of play, and on the other hand to increase play opportunities, in order to improve child and adolescent mental health.

The urban living condition during the last decades has affected the opportunity to play. Some of the main factors are associated with urban design, such as: the social distance between tenants caused by the contemporary living condition. Housing typologies detached from the public realm. The disappearance of spaces in between the public-private spheres, such as the court, the loggia or terrace where inhabitants interact and at watch their kids playing outside. The lack of nearby public facilities and playgrounds that promote the escalation of kids playing alone at home. The rise of crime. The lack of safety design.

On the other hand, there are also urban realities that have highlighted smart solutions to enhance play as a tool to reuse and reactivate wasted land of our contemporary society.

The urban living condition during the last decades has affected the opportunity to play. Some of the main factors are associated with urban design, such as: the social distance between tenants caused by the contemporary living condition. Housing typologies detached from the public realm. The disappearance of spaces in between the public-private spheres, such as the court, the loggia or terrace where inhabitants interact and at watch their kids playing outside. The lack of nearby public facilities and playgrounds that promote the escalation of kids playing alone at home. The rise of crime. The lack of safety design.

On the other hand, there are also urban realities that have highlighted smart solutions to enhance play as a tool to reuse and reactivate wasted land of our contemporary society.

Figure 3: The Dutch architect Aldo Van Eyck was probably the most important figure for the playful re-appropriation of the city. He built his first playground in Amsterdam in 1947 after the WWII as part of the Department of Urban Design and later on (in 1952) for the Municipality then in his own office. Between 1947 and 1978 Van Eyck designed hundreds of playgrounds. The historical context was the birth peak of the postwar baby boom, whereas almost no space for children was available, neither inside nor outside the house. These playgrounds represent one of the most emblematic architectural interventions: the shift from the top down organization of space by modernist functionalist architecture, towards a bottom up architecture. Van Eyck consciously designed play equipment in a very minimalist way, in order to stimulate children's imagination.

Copenhagen case study

‘Copenhagen's getting healthier, thanks to everyone in the city. The green, happy, cycle-friendly Danish capital is working with its citizens to create health-promoting urban design...already wears the crowns for being one of the world’s greenest, most liveable, most cycle friendly and happiest city. It has further ambitions to become the first carbon-neutral capital by 2025, to be smoke-free in the same time period, and to serve 90% organic food in all daycares, schools and homes for older people.’ (8)

Today the Danish capital city provides a model for urban design and healthy life. Indeed the recent headline of The Guardian evoked its uniqueness. So it might be useful to understand what is play’s role in this most livable of cities, and how play has been planned and designed.

The second part of the paper analyzes this contemporary case study that has spread the culture of the healthy and playable city. Firstly, it illustrates the historical milestones that have improved this unique culture, then it highlights the most effective urban design examples that have contributed to the rise of playable outdoor activity that is transforming Copenhagen’s identity.

Today the Danish capital city provides a model for urban design and healthy life. Indeed the recent headline of The Guardian evoked its uniqueness. So it might be useful to understand what is play’s role in this most livable of cities, and how play has been planned and designed.

The second part of the paper analyzes this contemporary case study that has spread the culture of the healthy and playable city. Firstly, it illustrates the historical milestones that have improved this unique culture, then it highlights the most effective urban design examples that have contributed to the rise of playable outdoor activity that is transforming Copenhagen’s identity.

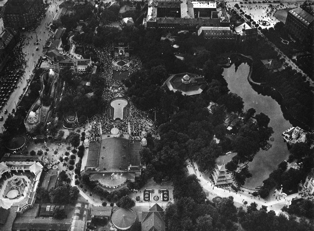

Figure 4: Eduard Spelterini, The Tivoli Garden

Tivoli garden opened in 1843 and it is the second oldest operating amusement park in the world, the first one is Bakken also in Denmark, and it is one of the most visited. The popularity and influence of Tivoli Garden - the word tivoli referred to Jardin de Tivoli in Paris that has been named after the Italian town of Tivoli nearby Rome - assumed in the Scandinavian region the synonyms of amusement park.

Tivoli garden opened in 1843 and it is the second oldest operating amusement park in the world, the first one is Bakken also in Denmark, and it is one of the most visited. The popularity and influence of Tivoli Garden - the word tivoli referred to Jardin de Tivoli in Paris that has been named after the Italian town of Tivoli nearby Rome - assumed in the Scandinavian region the synonyms of amusement park.

From top-down modernist dream to bottom-up urbanism of daily life

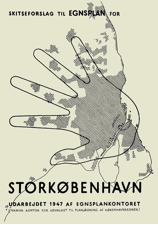

1947 was the starting point of a slow revolution that continues even today. The Regional Planning Office of Copenhagen, with the urban planners Rasmussen and Bredsdorff, conceived the Fingerplanen (Finger Plan), a strategic plan for the urban and economic development of the city towards the Greater Copenhagen Area after the WWII. The plan proposed to organize the city along five fingers corresponding to five main infrastructure corridors used by the citizens to commute in and out using the S-Train railway system and a new radial road network.

The infrastructure systems spread from the dense heart of central Copenhagen (the hand's palm), making the areas in between the fingers easily reachable for all citizens ,and they were kept empty for green, agricultural and play areas. The Finger Plan designed a modernist long term vision for Copenhagen that was slightly aligned with the other European urban dream: to bring the mechanical movement of transportation inside the city. Though, at the same time the plan aimed to give careful attention to the equilibrium between open spaces and recreational areas.

The infrastructure systems spread from the dense heart of central Copenhagen (the hand's palm), making the areas in between the fingers easily reachable for all citizens ,and they were kept empty for green, agricultural and play areas. The Finger Plan designed a modernist long term vision for Copenhagen that was slightly aligned with the other European urban dream: to bring the mechanical movement of transportation inside the city. Though, at the same time the plan aimed to give careful attention to the equilibrium between open spaces and recreational areas.

Figure 5: Fingerplanen, 1947 (historical picture)

This vision, along with other urban radical interventions (9), never actually happened, but it became an iconic proposal and urban guideline for the future. In fact, Copenhagen escaped from the concrete jungle that was instead chosen by the majority of European cities, according to urban planner Søren Elle, probably because: “We were lucky that Copenhagen was poor after the second world war”. (10) Simultaneously, there happened to be a group of Danish young architects who wanted to push cars and the concrete environment outside the city, proposing instead a type of urban planning focused on the 'people highway' (11). One of those young architects was Jan Gehl (1936), today a pioneer of the livable city: a different type of urbanism not based on a top-down action, but instead on an understanding of the city that puts people’s need, behavior and well-being first.

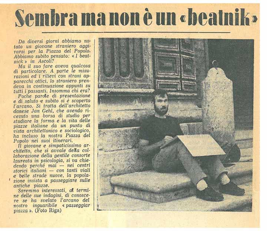

Figure 6: Jan Gehl in 1965 in Piazza del Popolo in Ascoli. The architect received a six-months grant study trip to travel in Italy in order to investigate Italian squares and daily public life. This is a local newspaper article of that time explaining to the citizens of Ascoli why they might spot a foreigner spending long time doing observations and measurement in their main square.

In 1971, the publication of the book Life in Between Building marked an important milestone for the dissemination of Gehl method in the urban studies. Together with his life partner, the psychologist Ingrid Mundt, they have been researching and establishing a methodology based on how people behave in public space and vice versa how the urban environment affects humans. Data collection regarding citizens' movement and behavior become precious information for governments and municipalities to make a participatory design proposals not based on a master-plan or top-down driven approach but instead on the small scale intervention of people's behavior.

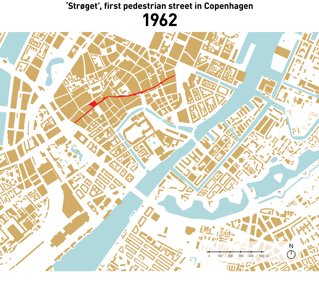

The first case study that inspired Jan Gehl was of Italian historical towns, examples of a public space based on human scale. Then came Copenhagen public spaces, with the first case study on the Strøget (the first pedestrian street of the city) in order to document the effects of pedestrianization on people's wellbeing; others followed in 1986, 1995 and 2005. The study brought evidence of city improvement after the pedestrianization. In light of the study's results, the City Council little by little removed parking lots and transformed them into public space: the private became public and collective, the concrete became more green. It is always hard to make these kinds of choices based on urban livability instead of urban profit, but the Gehl method facilitated these choices through providing compelling scientific evidence using data and analysis the effectiveness of the human centered urbanism.

The first case study that inspired Jan Gehl was of Italian historical towns, examples of a public space based on human scale. Then came Copenhagen public spaces, with the first case study on the Strøget (the first pedestrian street of the city) in order to document the effects of pedestrianization on people's wellbeing; others followed in 1986, 1995 and 2005. The study brought evidence of city improvement after the pedestrianization. In light of the study's results, the City Council little by little removed parking lots and transformed them into public space: the private became public and collective, the concrete became more green. It is always hard to make these kinds of choices based on urban livability instead of urban profit, but the Gehl method facilitated these choices through providing compelling scientific evidence using data and analysis the effectiveness of the human centered urbanism.

Figure 7: Gehl's Copenhagen analysis

Play as an urban tool to reuse the infrastructure

Five decades after the first Finger Plan, Copenhagen has a wide and well-preserved historical center, arguably the world's strongest bicycle culture, huge pedestrian and greenery spaces, the world's happiest people and in 2025 will become the first carbon-neutral capital. The Danish City is an urban model that many cities are trying to review in order to address their own poor urban choices made during the last century.

Recently, Copenhagen has enhanced even more the active behavior of its citizens; beyond the effective public transportation and the increasing number of walkable and bikeable spaces, the City is transforming the legacy of the harbor and other industrial spaces into a new public realm with playful activities. The waterfront redevelopment started in the early 2000s, and today consists of a network of open-air projects connected to the infrastructure system, new public space and playable activities. Furthermore, every project has been designed by worldwide famous young Danish architects that also show the exciting current debate on contemporary Danish Architecture.

The first project of this line was realized in 2003 by BIG Architect, the Danish based office with the charismatic leader Bjarke Ingels, titled Copenhagen Harbor Bath and the project is a free swimming-pool designed inside the harbor. It is a pivotal project that started the transformation from industrial port into a new social square for the city. Instead of designing a typical indoor swimming pool, the project evokes the free beach attitude, reinventing the Harbor's basic elements, and it has been described by Ingels: “When going to the beach or on holidays, it is usually to seek out exotic landscapes: the wide, open beach, the intimate lagoon, the rocky shore with cliffs and islands to jump from, the calm water or the big waves, the sand in the surf where the water is shallow and sand castles can be built. Rather than imitating the indoor swimming bath, the Harbour Bath offers an urban harbour landscape with dry-docks, cranes, piers, boat ramps, buoys, playgrounds and pontoons.”

The outdoor pool has become a free playground and an extension of the nearby park. It is intended for leisure, exercise and socializing, offering people spaces for sunbathing, swimming, jumping into the water from a terraced platform, or just enjoying and chilling with a view of the city. The material is wood that gives a sense of warm to the touch, even during the fall season. In fact the citizens love the space no matter the outside temperature. Some interviews conducted in the Harbour Bath revealed the people's affection for this project, both children and adults. The popularity of this project is transforming public opinion regarding the whole waterfront. (12)

Recently, Copenhagen has enhanced even more the active behavior of its citizens; beyond the effective public transportation and the increasing number of walkable and bikeable spaces, the City is transforming the legacy of the harbor and other industrial spaces into a new public realm with playful activities. The waterfront redevelopment started in the early 2000s, and today consists of a network of open-air projects connected to the infrastructure system, new public space and playable activities. Furthermore, every project has been designed by worldwide famous young Danish architects that also show the exciting current debate on contemporary Danish Architecture.

The first project of this line was realized in 2003 by BIG Architect, the Danish based office with the charismatic leader Bjarke Ingels, titled Copenhagen Harbor Bath and the project is a free swimming-pool designed inside the harbor. It is a pivotal project that started the transformation from industrial port into a new social square for the city. Instead of designing a typical indoor swimming pool, the project evokes the free beach attitude, reinventing the Harbor's basic elements, and it has been described by Ingels: “When going to the beach or on holidays, it is usually to seek out exotic landscapes: the wide, open beach, the intimate lagoon, the rocky shore with cliffs and islands to jump from, the calm water or the big waves, the sand in the surf where the water is shallow and sand castles can be built. Rather than imitating the indoor swimming bath, the Harbour Bath offers an urban harbour landscape with dry-docks, cranes, piers, boat ramps, buoys, playgrounds and pontoons.”

The outdoor pool has become a free playground and an extension of the nearby park. It is intended for leisure, exercise and socializing, offering people spaces for sunbathing, swimming, jumping into the water from a terraced platform, or just enjoying and chilling with a view of the city. The material is wood that gives a sense of warm to the touch, even during the fall season. In fact the citizens love the space no matter the outside temperature. Some interviews conducted in the Harbour Bath revealed the people's affection for this project, both children and adults. The popularity of this project is transforming public opinion regarding the whole waterfront. (12)

Figure 8 and 9: BIG Architect, Harbor Bath

Like Harbor Bath, the Islands Brygge Park (2012) is a development on the opposite side of the canal also aimed to attract people for leisure and playable activities in the water. This is a wide pathway designed by JSD Architect among the water consisting of different viewpoints and height into the city. The architect used materials such as wood or concrete to suggest a place for rest or transit, different spots to play and chill, aquatic and pedestrian activities like kayaking, biking, sunbathing or swimming. The walkways follow the sun's path over the year in order to maximize the sunny surface, especially in the big plazas that form the heart of the project and are always in full sunlight and full of people.

Figures 10 and 11: JSD Architect ,Islands Brygge Park

Another pivotal project in chronological order is the Cirkelbroen Bridge, realized by the Island-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, completed in 2015. The design recalls the feeling that the artist experienced in childhood in his hometown: jumping from boat to boat in the port. The project is a bridge composed by five circular platforms inspired by the boat’s design and it is part of a big loop around Copenhagen used for cycling, walking and running. The zigzag design aims to reduce the speed and bring people to relax, socialize and take a breath while admiring the city.

Figures 12 and 13: Olafur Eliasson, Cirkelbroen Bridge

The last project considered in this paper is the most ambitious action in the contemporary architecture scenario in the way that is possible to reuse an industrial fabric into an active playground for the citizens.

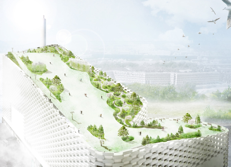

In 2017, construction commenced on Bjarke Ingels's Ski Slope Power Plant, a project for a new ultra-green waste energy power plant that simultaneously will become the biggest artificial ski slope in Denmark, despite its location in the industrial district of the capital. The Amager Bakke incinerator plant is part of the Danish City schedule to become the world’s first zero-carbon capital city by 2025 and its design moved from a simple monolithic industrial fabric towards a hybrid project that welcome new public activities. After the realization of this project, this country that is not famous for mountains or skiing activities will give to the citizens, for the first time, the possibility of improving their skiing abilities with a slope of 440 meters long and with four levels of difficulties, built over the power plant. Ski Slope Power Plant will become a new playable landmark for the city.

In 2017, construction commenced on Bjarke Ingels's Ski Slope Power Plant, a project for a new ultra-green waste energy power plant that simultaneously will become the biggest artificial ski slope in Denmark, despite its location in the industrial district of the capital. The Amager Bakke incinerator plant is part of the Danish City schedule to become the world’s first zero-carbon capital city by 2025 and its design moved from a simple monolithic industrial fabric towards a hybrid project that welcome new public activities. After the realization of this project, this country that is not famous for mountains or skiing activities will give to the citizens, for the first time, the possibility of improving their skiing abilities with a slope of 440 meters long and with four levels of difficulties, built over the power plant. Ski Slope Power Plant will become a new playable landmark for the city.

Figure 14: BIG Architect, Ski Slope Power Plant

Discussion

Copenhagen shows how active life becomes a daily tool for urban design and when it is properly applied, it introduces alternative and spontaneous scenarios, leading to the acquisition of a different vision of neighborhoods. Indeed, the interactive nature of game and ludic spaces seeks to relate spontaneously to individual behavior without affecting the freedom of the individuals themselves. Denmark is not new to innovative ideas that link design and user interaction, such as Lego (1932) or Noma restaurant (2004), and these projects mirror the bloom of today’s Danish architecture, where young designers interpret citizens' dreams and create new experimental way of living the public space.

Figure 15: No One Wins – Multibasket by Llobet & Pons, Teshima (Japan), photo Alice Covatta, 2017

The art installation was made for the Setouchi Triennale of 2013. It invites multiple residents to shoot at the same time bringing a new sense of collectivity into the community. This site-specific artwork is a reaction to the today’s condition of many Japanese islands where decreasing and aging populations give more and more empty spaces and old infrastructure to the towns and also lack of leisure spaces and playgrounds

The art installation was made for the Setouchi Triennale of 2013. It invites multiple residents to shoot at the same time bringing a new sense of collectivity into the community. This site-specific artwork is a reaction to the today’s condition of many Japanese islands where decreasing and aging populations give more and more empty spaces and old infrastructure to the towns and also lack of leisure spaces and playgrounds

Lessons from Copenhagen's' experience about how to design playable cities can be expanded into other urban realities through some strategic points.

1. Step by step

Copenhagen and its history from the Finger Plan to Jan Gehl to the more recent projects described in this paper teach us that to transform the urban condition into a more playful future needs a bottom-up approach. This brings together different figures, such as politicians, architects, psychologists and citizens, into a multidisciplinary and participatory process between research and design. It is also to be intended a process that can't happen overnight: it needs time and perseverance from this heterogeneous group in order to gradually instill a different urban identity.

2. Play as a sustainable design

Even though Copenhagen in the recent past was a Harbor City characterized by water insalubrity and pollution, the design of new water games has revealed the new sustainable aquatic condition achieved during the evolution from industrial to post-industrial status. As a consequence, it stimulates new ways to re-appropriate the industrial legacy that goes hand to hand with people life style and wellbeing. Play and enjoining the public sphere of the city, that in the past belonged to the industries or today is designed for it, triggered a new trust between the citizens and city council, stimulating a new awareness by the citizens of Copenhagen progress toward a more sustainable future.

3. Reuse the wasteland

The industrial fabric has been always seen as a mono-functional (and hidden) space built in order to improve city growth physically and economically. The Amager Bakke incinerator plant and the Copenhagen Harbor Bath projects are examples of how to reuse these kind of spaces. The first will add the layer of play into a new industrial incinerator while the second added play into a reclaimed industrial waterfront. Both projects are transforming industrial scale into the human dimension through the appropriation of play. These strategies are needed in future urban conditions where more and more wasted spaces are produced as consequence of the population shrinkage and the decentralization of the industrial activities. City governments have new potential spaces to be reused and re-densified into playground.

4. Playground for the twenty-first century

The reuse of wasted land provides wider spaces inside the city center where playful activities can also reach the size of extreme sport like skiing or kayaking. The design is in-between safeness and wilderness, and it can attract citizens of all ages who are not interested in the typical idea of 'playground' as a quiet zone in between buildings. In this sense, playground design needs to move into a new paradigm that embraces the ambiguity and flexibility of the new shapes of play, moving from a mono-functional and static state of the modernism period to a mixed and flexible approach that becomes part of people's daily life.

5. Healthy City

The World Health Organization defines the concept of Healthy City as addressing each of physical, mental and social well-being: "a healthy city is one that continually creates and improves its physical and social environments and expands the community resources that enable people to mutually support each other in performing all the functions of life and developing to their maximum potential."(13)

The Copenhagen Harbor Bath, the Islands Brygge Park, the Cirkelbroen Bridge and the Ski Slope Power Plant are examples of how play can become a tool to achieve the status of Healthy City because it reaches people of all ages and can have positive impact mentally, physically and socially.

1. Step by step

Copenhagen and its history from the Finger Plan to Jan Gehl to the more recent projects described in this paper teach us that to transform the urban condition into a more playful future needs a bottom-up approach. This brings together different figures, such as politicians, architects, psychologists and citizens, into a multidisciplinary and participatory process between research and design. It is also to be intended a process that can't happen overnight: it needs time and perseverance from this heterogeneous group in order to gradually instill a different urban identity.

2. Play as a sustainable design

Even though Copenhagen in the recent past was a Harbor City characterized by water insalubrity and pollution, the design of new water games has revealed the new sustainable aquatic condition achieved during the evolution from industrial to post-industrial status. As a consequence, it stimulates new ways to re-appropriate the industrial legacy that goes hand to hand with people life style and wellbeing. Play and enjoining the public sphere of the city, that in the past belonged to the industries or today is designed for it, triggered a new trust between the citizens and city council, stimulating a new awareness by the citizens of Copenhagen progress toward a more sustainable future.

3. Reuse the wasteland

The industrial fabric has been always seen as a mono-functional (and hidden) space built in order to improve city growth physically and economically. The Amager Bakke incinerator plant and the Copenhagen Harbor Bath projects are examples of how to reuse these kind of spaces. The first will add the layer of play into a new industrial incinerator while the second added play into a reclaimed industrial waterfront. Both projects are transforming industrial scale into the human dimension through the appropriation of play. These strategies are needed in future urban conditions where more and more wasted spaces are produced as consequence of the population shrinkage and the decentralization of the industrial activities. City governments have new potential spaces to be reused and re-densified into playground.

4. Playground for the twenty-first century

The reuse of wasted land provides wider spaces inside the city center where playful activities can also reach the size of extreme sport like skiing or kayaking. The design is in-between safeness and wilderness, and it can attract citizens of all ages who are not interested in the typical idea of 'playground' as a quiet zone in between buildings. In this sense, playground design needs to move into a new paradigm that embraces the ambiguity and flexibility of the new shapes of play, moving from a mono-functional and static state of the modernism period to a mixed and flexible approach that becomes part of people's daily life.

5. Healthy City

The World Health Organization defines the concept of Healthy City as addressing each of physical, mental and social well-being: "a healthy city is one that continually creates and improves its physical and social environments and expands the community resources that enable people to mutually support each other in performing all the functions of life and developing to their maximum potential."(13)

The Copenhagen Harbor Bath, the Islands Brygge Park, the Cirkelbroen Bridge and the Ski Slope Power Plant are examples of how play can become a tool to achieve the status of Healthy City because it reaches people of all ages and can have positive impact mentally, physically and socially.

References

- "Victor Turner calls play 'liminal' or 'liminoid', meaning that it occupies a threshold between reality and unreality, as if, for example, it were on the beach between the land and the see" in Sutton-Smith B (2001) The ambiguity of play. Harvard University Press. pp.1

- Huizinga J, Schendel Cvon. (1972) Homo ludens. Einaudi. pp.8

- Caillois R (2001) Man, play and games. University of Illinois Press. pp.6

- Huizinga J, Schendel Cvon. (1972) Homo ludens. Einaudi. pp.8

- Gray, P. (2011). The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents s. American Journal of Play, 3 (4), 443–463. Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/files/attachments/1195/ajp-decline-play-published.pdf

- ibidem

- ibidem

- Cathcart-Keays, A. (2016, September 16). Copenhagen's getting healthier, thanks to everyone in the city. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/public-leaders-network/2016/sep/16/copenhagen-healthier-city-cycling-denmark-car-free-environment

- Other projects were the Lake Ring proposed in 1958 for a 12 lanes road from the city center to the lake or the City Vest that planned to demolish the Vesterbo neighborhood in order to create space for a motorway and new high-rise buildings

- Cathcart-Keays, A. (2016, May 05). Story of cities #36: How Copenhagen rejected 1960s modernist 'utopia'. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/05/story-cities-copenhagen-denmark-modernist-utopia

- ibidem

- Wonderful Copenhagen. “Copenhagen Harbour - You Can Swim in It!” YouTube, YouTube, 16 Dec. 2009, www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQ9-t7P1jCc.

- What is a healthy city? (2018, January 13). Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/activities/healthy-cities/who-european-healthy-cities-network/what-is-a-healthy-city

Further reading

Amy J. Morgan. (2013, August,Volume 16, Number 4 ) Exercise and Mental Health: An Exercise and Sports Science Australia Commissioned Review. Journal of Exercise Physiologyonline

Caillois R (2001) Man, play and games. University of Illinois Press

Cathcart-Keays, A. (2016, September 16). Copenhagen's getting healthier, thanks to everyone in the city. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/public-leaders-network/2016/sep/16/copenhagen-healthier-city-cycling-denmark-car-free-environment

Cathcart-Keays, A. (2016, May 05). Story of cities #36: How Copenhagen rejected 1960s modernist 'utopia'. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/05/story-cities-copenhagen-denmark-modernist-utopia

Gehl, J., Svarre, B., & Steenhard, K. A. (2013). How to study public life. Island Press.

Gehl, J., & Koch, J. (2011). Life between buildings: Using public space. Island Press.

Gray, P. (2011). The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents s. American Journal of Play,3(4), 443–463.Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/files/attachments/1195/ajp-decline-play-published.pdf

Huizinga J, Schendel Cvon. (1972) Homo ludens. Einaudi. How urban design can impact mental health. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.urbandesignmentalhealth.com/how-urban-design-can-impact-mental-health.html

Ingels, B. (2009). Yes is more: An archicomic on architectural evolution: BIG, Bjarke Ingels Group. Evergreen.

Lefaivre L, Roode Ide, Fuchs R (2002) Aldo van Eyck: the playgrounds and the city. Stedelijk Museum

Nakamura, H. (2010). Microscopic designing methodology. Tokyo: Inax Publishing.

Stathopoulou, G., Powers, M. B., Berry, A. C., Smits, J. A., & Otto, M. W. (2006, 05). Exercise Interventions for Mental Health: A Quantitative and Qualitative Review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(2), 179-193. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00021.x

What is a healthy city? (2018, January 13). Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/activities/healthy-cities/who-european-healthy-cities-network/what-is-a-healthy-city

Sutton-Smith B (2001) The ambiguity of play. Harvard University Press

TEDxTalks (2014) The decline of play | Peter Gray | TEDxNavesink. In: YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bg-GEzM7iTk

Tsukamoto, Y., & Kaijima, M. (2010). Behaviorology. New York: Rizzoli.

Caillois R (2001) Man, play and games. University of Illinois Press

Cathcart-Keays, A. (2016, September 16). Copenhagen's getting healthier, thanks to everyone in the city. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/public-leaders-network/2016/sep/16/copenhagen-healthier-city-cycling-denmark-car-free-environment

Cathcart-Keays, A. (2016, May 05). Story of cities #36: How Copenhagen rejected 1960s modernist 'utopia'. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/05/story-cities-copenhagen-denmark-modernist-utopia

Gehl, J., Svarre, B., & Steenhard, K. A. (2013). How to study public life. Island Press.

Gehl, J., & Koch, J. (2011). Life between buildings: Using public space. Island Press.

Gray, P. (2011). The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents s. American Journal of Play,3(4), 443–463.Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/files/attachments/1195/ajp-decline-play-published.pdf

Huizinga J, Schendel Cvon. (1972) Homo ludens. Einaudi. How urban design can impact mental health. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.urbandesignmentalhealth.com/how-urban-design-can-impact-mental-health.html

Ingels, B. (2009). Yes is more: An archicomic on architectural evolution: BIG, Bjarke Ingels Group. Evergreen.

Lefaivre L, Roode Ide, Fuchs R (2002) Aldo van Eyck: the playgrounds and the city. Stedelijk Museum

Nakamura, H. (2010). Microscopic designing methodology. Tokyo: Inax Publishing.

Stathopoulou, G., Powers, M. B., Berry, A. C., Smits, J. A., & Otto, M. W. (2006, 05). Exercise Interventions for Mental Health: A Quantitative and Qualitative Review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(2), 179-193. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00021.x

What is a healthy city? (2018, January 13). Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/activities/healthy-cities/who-european-healthy-cities-network/what-is-a-healthy-city

Sutton-Smith B (2001) The ambiguity of play. Harvard University Press

TEDxTalks (2014) The decline of play | Peter Gray | TEDxNavesink. In: YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bg-GEzM7iTk

Tsukamoto, Y., & Kaijima, M. (2010). Behaviorology. New York: Rizzoli.

About the Author

|

Alice Covatta is an Italian Visiting Researcher in Architecture and Urban Design at Keio University in Tokyo and a UD/MH Fellow. She has been granted by Japan Foundation Fellowship with the investigation entitled ‘Tokyo Playground: the Interplay between Infrastructure and Collective Space’. Her focusses of investigation are spontaneous urban scenarios aimed at the improvement of the livability of public spaces and spaces that have potential to become a meaningful part of a bottom-up design process that enhances community and generational cooperation. Her works have been exposed at MAXXI Museum in Rome and Venice Biennale, and recently won the "Europan14" for the city of Neu-Ulm in Germany. She is correspondent in Japan for Domus and collaborator of Warehouse TERRADA in Tokyo, dealing with the promotion of art projects in between Japan and European countries

|