Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2018;4:8

RESEARCH & ANALYSIS

A city of happy captives: a study of perceived livability in contemporary urban Gurgaon, India

Avtar Bhalla and Sayna Anand

Sushant School of Art and Architecture, India

Sushant School of Art and Architecture, India

“Cities should make us happy by fostering emotionally intelligent design and creating closely connected communities, with the benefits shared by everyone” - Charles Montgomery, Happy City

INTRODUCTION

Humans implicitly absorb the character of their surroundings (Beard 2016). Our surroundings impart comparable thought processes, grouping similar people together. The environment acts as a stimulus to human response. The more the respondents find their city as beautiful, clean, and safe, the more likely they are to report being happy (Benfield 2012). Our environment as tangible or intangible gives rise to diverse spatial experiences which eventually guide our psyche.

Happiness at an individual level is affected by people's various needs such as income, health and wellbeing, and recreational activities amongst others. The ultimate goal of designing cities for urban designers and planners is to create a happy environment for people to live in and to cherish their existence. In this context, happiness may be considered synonymous with satisfaction and achieving a good quality of life. In this paper, we review factors that can impact happiness within an environment.

The city caters to the needs of an individual in terms of economy, infrastructure or a social network. This has given the city a specific image, reflecting happiness within it in a distinct way. Bogotá is an example of a successful happy city, transformed from an originally segregated and low income city. Despite its economic challenges, the experiments by Mayor Enrique Peñalosa made other intangible aspects of the city come alive, such as emotions, and freedom of movement that were earlier curbed by private vehicles and privatised public spaces. Before 1903, no city had a traffic code (Montgomery 1968). Streets were for everyone, a shared space for playgrounds, parks and markets before cars took over the city. In Bogota, a great deal of money was invested in creating public infrastructure such as bike paths and public transit systems, that helped revive abandoned streets into child-friendly and walkable spaces. This was achieved in the year 2000 through banning cars on streets three times a week. Despite comparatively low economic output, the city became a happy place for its people.

In the Indian context, we compare the happiness as utopia vs happiness from the bottom up. By analysing the contemporary urban space of Gurgaon, through the environment stimuli, panopticon theory (1), synopticon framework (2), and windshield commuting (3), we try to build a case for happy cities.

Gurgaon in the 1970s was a land of villages, located on the outskirts of the capital of the capital of India, Delhi. Steadily, driven by approaching private developers such as DLF, private development began in earnest. The past two decades have been a time of transformation for the city. With Delhi being congested, people of NCR (National Capital Region) began to buy the properties in Gurgaon which were being developed by the private companies. International investment followed, and there was an economic boom to the city. The companies which came in brought job opportunities which further increased the influx of the people, especially in the IT sector. Today, with this immense growth, we know Gurgaon as 'millennium city'. Gurgaon is now considered as an urban utopia by the people of the NCR. It provides an economic boomtown to the region, creating a huge number of job opportunities. Yet the city lies fragmented as the privately owned properties were discretely developed with associated amenities, but as a city beyond the private communities, connectivity is missing (Yardley n.d.). The priority of Gurgaon's residents is not happiness but safety. And perhaps at times they are considered synonymous.

METHODS

The findings of the research paper are based on personal interviews with 16 residents of Nirvana Country, South city gated communities in Gurgaon and undertaken during their visits to the market. 10% of interviewees were under the age of 30, 70% were middle-aged, and 20% were over the age of 65.

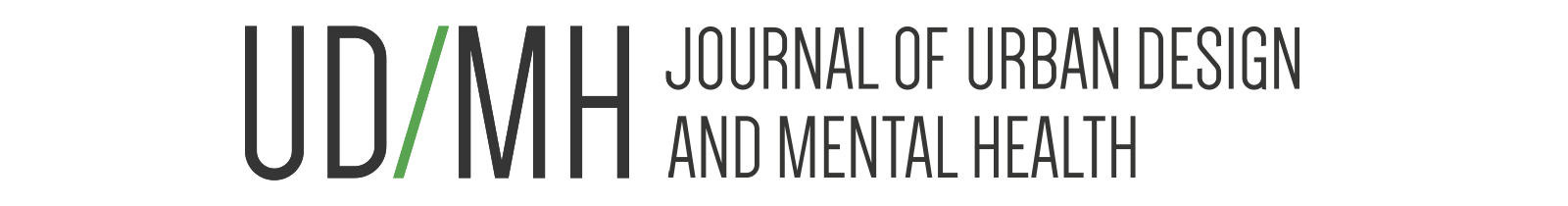

Maps from ArcGIS software were used to calculate the boundaries formed by these gated utopias.

RESULTS

Fragmented 'utopias' in the city

In a liberal society and a democratic country like India, we still hold on to the thoughts and traditions of the old times but with a modern outlook. And yet, it is a rather significant existing problem to be solved. As a society, we are trying to retrofit the happiness factor in a spatial context by considering each social class individually. In the rapidly growing global city of Gurgaon, we come across discrete spaces, to evaluate the happiness quotient that divides society. The citizenships formed within the fragmented spaces of Gurgaon are the expression of a state of exception, as a mode of new liberal production, differentially and contradictorily expressed to produce a splintered territorialisation of citizenship (Roy and Alsayyad 2006). Most attention is focused on people with a sound economic background and with adequate amenities, and the dominant demographic is the technically sound and the highly qualified working class attracted by work for big corporates and multinationals. City developers such as DLF, Ansals and Unitech are accordingly directing development, constantly trying to fulfil their various needs within the same territory by creating gated communities that have become private urban utopias.

Happiness at an individual level is affected by people's various needs such as income, health and wellbeing, and recreational activities amongst others. The ultimate goal of designing cities for urban designers and planners is to create a happy environment for people to live in and to cherish their existence. In this context, happiness may be considered synonymous with satisfaction and achieving a good quality of life. In this paper, we review factors that can impact happiness within an environment.

The city caters to the needs of an individual in terms of economy, infrastructure or a social network. This has given the city a specific image, reflecting happiness within it in a distinct way. Bogotá is an example of a successful happy city, transformed from an originally segregated and low income city. Despite its economic challenges, the experiments by Mayor Enrique Peñalosa made other intangible aspects of the city come alive, such as emotions, and freedom of movement that were earlier curbed by private vehicles and privatised public spaces. Before 1903, no city had a traffic code (Montgomery 1968). Streets were for everyone, a shared space for playgrounds, parks and markets before cars took over the city. In Bogota, a great deal of money was invested in creating public infrastructure such as bike paths and public transit systems, that helped revive abandoned streets into child-friendly and walkable spaces. This was achieved in the year 2000 through banning cars on streets three times a week. Despite comparatively low economic output, the city became a happy place for its people.

In the Indian context, we compare the happiness as utopia vs happiness from the bottom up. By analysing the contemporary urban space of Gurgaon, through the environment stimuli, panopticon theory (1), synopticon framework (2), and windshield commuting (3), we try to build a case for happy cities.

Gurgaon in the 1970s was a land of villages, located on the outskirts of the capital of the capital of India, Delhi. Steadily, driven by approaching private developers such as DLF, private development began in earnest. The past two decades have been a time of transformation for the city. With Delhi being congested, people of NCR (National Capital Region) began to buy the properties in Gurgaon which were being developed by the private companies. International investment followed, and there was an economic boom to the city. The companies which came in brought job opportunities which further increased the influx of the people, especially in the IT sector. Today, with this immense growth, we know Gurgaon as 'millennium city'. Gurgaon is now considered as an urban utopia by the people of the NCR. It provides an economic boomtown to the region, creating a huge number of job opportunities. Yet the city lies fragmented as the privately owned properties were discretely developed with associated amenities, but as a city beyond the private communities, connectivity is missing (Yardley n.d.). The priority of Gurgaon's residents is not happiness but safety. And perhaps at times they are considered synonymous.

METHODS

The findings of the research paper are based on personal interviews with 16 residents of Nirvana Country, South city gated communities in Gurgaon and undertaken during their visits to the market. 10% of interviewees were under the age of 30, 70% were middle-aged, and 20% were over the age of 65.

Maps from ArcGIS software were used to calculate the boundaries formed by these gated utopias.

RESULTS

Fragmented 'utopias' in the city

In a liberal society and a democratic country like India, we still hold on to the thoughts and traditions of the old times but with a modern outlook. And yet, it is a rather significant existing problem to be solved. As a society, we are trying to retrofit the happiness factor in a spatial context by considering each social class individually. In the rapidly growing global city of Gurgaon, we come across discrete spaces, to evaluate the happiness quotient that divides society. The citizenships formed within the fragmented spaces of Gurgaon are the expression of a state of exception, as a mode of new liberal production, differentially and contradictorily expressed to produce a splintered territorialisation of citizenship (Roy and Alsayyad 2006). Most attention is focused on people with a sound economic background and with adequate amenities, and the dominant demographic is the technically sound and the highly qualified working class attracted by work for big corporates and multinationals. City developers such as DLF, Ansals and Unitech are accordingly directing development, constantly trying to fulfil their various needs within the same territory by creating gated communities that have become private urban utopias.

Figure 1: 500m radius circles around some of the gated communities in Gurgaon (ARCGIS)

Some such examples of developments within Gurgaon include communities such as Nirvana Country, South City 1 and World Spa. These private enclaves are spreading throughout the city and are favoured by potential buyers. An interesting observation in one of these islands, Nirvana Country was that ‘the people were indeed very happy’. The entrance of the island is guarded with a security check, beyond which this society extends as a city in itself. Having dedicated areas for a specific purpose is not always negative to the urban form of the city but as to how equitable they are, these choices may define the social viability of the place. We analysed the factors that promote this kind of living that is widely spreading through the city. Some of the key features highlighted for the purpose of marketing include: art of better living; exclusive villas amidst greenery; secure elite neighbourhood; clubhouses to enjoy with friends and family; quality education for children within a 5 minute walk; and integrated servant quarters.

The sellers portray these gated communities as a dream for better living by describing them as “heaven on earth”, justifying the investment of the buyer in return for luxury facilities that can make them feel like an emperor or empress. These facilities include gymnasiums, therapy centres, swimming pools, and meditation centres amongst others. In terms of the urban fabric, the boundary walls create a visual screening that defines not only the property line but also the limit of access. The internal land uses are segregated, with low mixed-use integration. Inside the fortification, the urban form promotes communal living with no boundary walls. People within the society meet for weekly gatherings in the park, which is an important behavioural aspect promoting a healthy living environment.

Safety and Fear

The developers of gated societies, under the aegis of emotions like fear, advertise their developments and advocate for a happy environment prevalent within the gated society. The owners of these developments highlight how safe the environment is, guarded by cameras, security guards and checkpoints at every entrance and exit. Most residential areas in Gurgaon are gated, and any residents outside gated areas seek to keep guards outside their houses. There are about 250 private security service companies in Gurgaon with over 35,000 security guards against 3100 public police (Rajagopalan, Tabarrok 2014); everything is under surveillance to ensure people's security, and the commonly-expressed emotion within these communities was the importance of safety. The areas of Gurgaon that do not lie within guarded zones are not generally considered to be places where time can be safely spent alone, pedestrians can be seen hurrying to cross the roads to reach gated areas, and most people avoid these areas after 7pm. Their concerns may be justified: a safety audit conducted recently by social enterprise Safetipin found that all major corporate or commercial hubs in Gurgaon scored low on safety parameters.

Our interactions with the residents of Nirvana Country found many residents stating security as the first point in their checklist of priorities, and their most important consideration while choosing to live in the society. The developers specifically highlighted that they have about 15 to 20 guards and cameras ensuring the security and safety of the residents within each apartment building or society. The residents also stated the importance of the limitation of diversity within their community, confining their interactions to people from similar income groups and so-called 'like-minded' people. One resident of Nirvana country explained: “We are living among similar kind of people in one place”.

Ultimately, these people live and interact within a guarded territory that is ostensibly inclusive, happy and satisfied within a secured boundary, but the experience outside the periphery is dramatically different, resulting in a feeling of being unprotected when not in the enclave, which gives rise to fear and discomfort. The question here is whether similar income groups and like-minded people in a safe and secure environment result in contented living and justify the need of these utopias? Or is communal living with diversity more likely to promote healthy and happy living?

Safety and Fear

The developers of gated societies, under the aegis of emotions like fear, advertise their developments and advocate for a happy environment prevalent within the gated society. The owners of these developments highlight how safe the environment is, guarded by cameras, security guards and checkpoints at every entrance and exit. Most residential areas in Gurgaon are gated, and any residents outside gated areas seek to keep guards outside their houses. There are about 250 private security service companies in Gurgaon with over 35,000 security guards against 3100 public police (Rajagopalan, Tabarrok 2014); everything is under surveillance to ensure people's security, and the commonly-expressed emotion within these communities was the importance of safety. The areas of Gurgaon that do not lie within guarded zones are not generally considered to be places where time can be safely spent alone, pedestrians can be seen hurrying to cross the roads to reach gated areas, and most people avoid these areas after 7pm. Their concerns may be justified: a safety audit conducted recently by social enterprise Safetipin found that all major corporate or commercial hubs in Gurgaon scored low on safety parameters.

Our interactions with the residents of Nirvana Country found many residents stating security as the first point in their checklist of priorities, and their most important consideration while choosing to live in the society. The developers specifically highlighted that they have about 15 to 20 guards and cameras ensuring the security and safety of the residents within each apartment building or society. The residents also stated the importance of the limitation of diversity within their community, confining their interactions to people from similar income groups and so-called 'like-minded' people. One resident of Nirvana country explained: “We are living among similar kind of people in one place”.

Ultimately, these people live and interact within a guarded territory that is ostensibly inclusive, happy and satisfied within a secured boundary, but the experience outside the periphery is dramatically different, resulting in a feeling of being unprotected when not in the enclave, which gives rise to fear and discomfort. The question here is whether similar income groups and like-minded people in a safe and secure environment result in contented living and justify the need of these utopias? Or is communal living with diversity more likely to promote healthy and happy living?

Figure 4: Guards at the entrance to a gated community in Gurgaon

Though surveillance (panopticism) is often considered a boon by society nowadays, providing security and surety with cameras watching over us over all the time, the feeling of being watched, apart from curbing criminal activities, also becomes an important tool to seed the territories of fear in areas previously open and accessible to the public. Although it justifies people walking fearlessly in those specific areas, it presents itself as a physical marker segregating safe from unsafe spaces. The impact of demanded emotional aspects makes human beings vulnerable to the environment forced upon them. As we discuss the case of the urban island of Nirvana Country, we come across a feeling of fear that overpowers these residents when they are not within the guarded areas of society. As Nirvana Country residents noted: “I feel a discomfort once I move out of this society... The city outside of these walls demands you to take your car out for any work... I can’t send my daughter alone, I prefer sending her by car... When there is no one and no light on the street, I don’t feel comfortable walking in the evening”. A resident of Nirvana Spa noted: “I don’t want my children to get out on the streets of Gurgaon and be run over by car, so I prefer to live in a gated community; my child’s safety is my first priority.”

The developers capitalise on the power of fear to help sell their developments, a strategy that is expanding to the whole city. Synopticism has failed: many eyes on street or mixed uses in this case do not compliment the environment of this city. The city seeks to cater to this by increasing surveillance and designated use of space. ‘The city is moving towards developing controlled public activity spaces’ says sociologist Sanjay Srivastava. The marked territories of public spaces, malls, housing societies, schools and marketplaces are guarded and even controlled in terms of functions and accessibility and modify the happiness quotient of the city.

It is important to understand experiential qualities of spaces whether dynamic or static. If there is no perceived freedom of walking, playing around in streets of the city, thus we end up making secluded spaces of happiness with freedom inside. Within their own protected society, people walk or cycle from one place to another because the streets are very comforting not only in terms of security but also the street character, designed to promote walking. To enhance the happiness of the city, freedom of people is important but the canvas of the memories of city dwellers is filled with feelings that run around insecurity and controlled utopian happiness.

The developers capitalise on the power of fear to help sell their developments, a strategy that is expanding to the whole city. Synopticism has failed: many eyes on street or mixed uses in this case do not compliment the environment of this city. The city seeks to cater to this by increasing surveillance and designated use of space. ‘The city is moving towards developing controlled public activity spaces’ says sociologist Sanjay Srivastava. The marked territories of public spaces, malls, housing societies, schools and marketplaces are guarded and even controlled in terms of functions and accessibility and modify the happiness quotient of the city.

It is important to understand experiential qualities of spaces whether dynamic or static. If there is no perceived freedom of walking, playing around in streets of the city, thus we end up making secluded spaces of happiness with freedom inside. Within their own protected society, people walk or cycle from one place to another because the streets are very comforting not only in terms of security but also the street character, designed to promote walking. To enhance the happiness of the city, freedom of people is important but the canvas of the memories of city dwellers is filled with feelings that run around insecurity and controlled utopian happiness.

Windshield commuting versus thoughtful commuting

Feelings of insecurity significantly influence mobility within the city. Gurgaon’s private urban utopias may be complete in themselves, but residents eventually have to move out of the boundaries for work and other activities. Some of the factors we use to evaluate the quality of our commute from one place to the other include: expected time of arrival, distance covered, possible safest and the fastest route available, and work to be accomplished. We may also consider the condition of the local/public transport facilities. Although people prefer short commuting distances, the development of these communities increases the distances, resulting in longer commutes which has the risk of reducing residents' happiness quotient. Segregated spaces attract personalised modes of transport that affect commuting through the city beyond the community gates: people avoid walking, and prefer to leave from home in a secured moving box to reach another secure territory, and the city beyond the windshield seems inconsequential to them. Gurgaon's roads are dominated by cars and the city adds up to 60,000 cars per month (Rajagopalan, Tabarrok 2014). Our journey gives rise to various momentary thoughts of the past, present and what is yet to come, creating a trail of memories. If all one observes is a city landscape dominated by cars and traffic jams with minimal space for pedestrians, this can further increases frustration levels and disconnection, driving up road rage. This may be leading to a reclusive society, a loss of civic responsibility, and diminished happiness.

The street network is the key underlying framework in the design of a city which brings the city together as one and acts as a common link for the urban spaces. The street network of Gurgaon guides the spatial structure of the city which is dominated by isolated super blocks and commutes are often associated with negative thoughts during transit, rather than good memories. These momentary feelings are influenced by views, invariably from the windshield.

Feelings of insecurity significantly influence mobility within the city. Gurgaon’s private urban utopias may be complete in themselves, but residents eventually have to move out of the boundaries for work and other activities. Some of the factors we use to evaluate the quality of our commute from one place to the other include: expected time of arrival, distance covered, possible safest and the fastest route available, and work to be accomplished. We may also consider the condition of the local/public transport facilities. Although people prefer short commuting distances, the development of these communities increases the distances, resulting in longer commutes which has the risk of reducing residents' happiness quotient. Segregated spaces attract personalised modes of transport that affect commuting through the city beyond the community gates: people avoid walking, and prefer to leave from home in a secured moving box to reach another secure territory, and the city beyond the windshield seems inconsequential to them. Gurgaon's roads are dominated by cars and the city adds up to 60,000 cars per month (Rajagopalan, Tabarrok 2014). Our journey gives rise to various momentary thoughts of the past, present and what is yet to come, creating a trail of memories. If all one observes is a city landscape dominated by cars and traffic jams with minimal space for pedestrians, this can further increases frustration levels and disconnection, driving up road rage. This may be leading to a reclusive society, a loss of civic responsibility, and diminished happiness.

The street network is the key underlying framework in the design of a city which brings the city together as one and acts as a common link for the urban spaces. The street network of Gurgaon guides the spatial structure of the city which is dominated by isolated super blocks and commutes are often associated with negative thoughts during transit, rather than good memories. These momentary feelings are influenced by views, invariably from the windshield.

CONCLUSION

A City of Happy Captives

Living within a secluded, exclusive urban 'utopia' may create feelings of security and happiness, justifying their created environments, but as a part of the larger city, people live in many separate islands. This has resulted in a ‘City of Captive Happiness’. Overall, the city lacks a homogeneous experiential quality or shared identity beyond these utopias. People living in different communities seek to surround themselves with people who share similar mindsets, and there is a feeling of superiority in the people living inside the costlier gated communities. They interact less with the people outside and are well connected inside these communities. Therefore, to a migrant, the city can seem reserved with a culture of happiness confined to exclusive, enclosed spaces, creating constrained movement out of these comfort zones. As a result, a cyclic process manifests within the city development. At first, private living spaces are created followed by hiring of security personnel to watch over, instilling fear beyond the boundary, and finally resulting in use of cars to commute and rule out unsafe walking scenarios. This eventually promotes confined living as a preferred environment. Conservative or private living is not seen as a negative for this society since these enclaves are popularly considered to nurture a safe and happy environment for the people living in them. However, interestingly, the edges of these islands become deserted because the cores of potential happiness (shopping areas, restaurants, cafes, parks and open spaces) in those private utopias are primarily centred within these separate, exclusive islands. Meanwhile, people passing through the streets extrinsic to these societies witness no activity on the street at all.

The elimination of these territories completely may not be the solution since it is the need of the hour. However, distributing the cores of activities towards the external street edges may result in a more vibrant living environment similar to a colonnaded edge on a commercial street providing an interactive public edge.

Security and commuting is a major contributor to the happiness of the cities. When we let a certain emotion overpower our minds and urban spaces, we neglect various other sensitive psychological issues which are interlinked and can help to actually create a balanced environment within our cities. Urban practitioners and decision makers have an inclination towards creating walkable, dense and mixed-use urban developments to promote healthy lifestyle towards achieving happy cities.

Living within a secluded, exclusive urban 'utopia' may create feelings of security and happiness, justifying their created environments, but as a part of the larger city, people live in many separate islands. This has resulted in a ‘City of Captive Happiness’. Overall, the city lacks a homogeneous experiential quality or shared identity beyond these utopias. People living in different communities seek to surround themselves with people who share similar mindsets, and there is a feeling of superiority in the people living inside the costlier gated communities. They interact less with the people outside and are well connected inside these communities. Therefore, to a migrant, the city can seem reserved with a culture of happiness confined to exclusive, enclosed spaces, creating constrained movement out of these comfort zones. As a result, a cyclic process manifests within the city development. At first, private living spaces are created followed by hiring of security personnel to watch over, instilling fear beyond the boundary, and finally resulting in use of cars to commute and rule out unsafe walking scenarios. This eventually promotes confined living as a preferred environment. Conservative or private living is not seen as a negative for this society since these enclaves are popularly considered to nurture a safe and happy environment for the people living in them. However, interestingly, the edges of these islands become deserted because the cores of potential happiness (shopping areas, restaurants, cafes, parks and open spaces) in those private utopias are primarily centred within these separate, exclusive islands. Meanwhile, people passing through the streets extrinsic to these societies witness no activity on the street at all.

The elimination of these territories completely may not be the solution since it is the need of the hour. However, distributing the cores of activities towards the external street edges may result in a more vibrant living environment similar to a colonnaded edge on a commercial street providing an interactive public edge.

Security and commuting is a major contributor to the happiness of the cities. When we let a certain emotion overpower our minds and urban spaces, we neglect various other sensitive psychological issues which are interlinked and can help to actually create a balanced environment within our cities. Urban practitioners and decision makers have an inclination towards creating walkable, dense and mixed-use urban developments to promote healthy lifestyle towards achieving happy cities.

Figure 5: Deserted streets in the spaces between gated communities, and diagram showing how activity could be shifted to the edge

These suggestive measures may bring the people onto the streets and a secure environment outside the society gates, rendering surveillance and guarding of spaces as less essential for residents. There is no space for fear in happy cities. The cities that are economically, physically and socially enriched present themselves as happy cities, whereas cities with low physical and social integration tend to back fit the missing aspects of the urban environment. In the case of Gurgaon, which we observe as an island grown economically and physically with low integration of the social environment in the urban spaces at city scale, creates an imbalance and a low happiness factor within the city. Thus, these territories not only create an emotional imbalance for city dwellers but also create social segregation at the city level.

Footnotes

1. Panopticon is a theory proposed by Jeremy Bentham in the form of the circular building with an observation tower in the centre of an open space enclosed by a wall. Michel Foucault’s conceptualisation of the panopticon [few see many] elaborates on surveillance in his book Discipline & Punish, 1975.

2. Thomas Mathieson introduces the anti-theory Synopticon [many see the few].

3. Winsdshield commuting refers to the commute from one place to another by car; its windshield is the medium of interaction with the world outside.

2. Thomas Mathieson introduces the anti-theory Synopticon [many see the few].

3. Winsdshield commuting refers to the commute from one place to another by car; its windshield is the medium of interaction with the world outside.

References

Beard, Bill. “The Modern Built Environment| Journal of the Mental Environment.” Adbusters | Journal of the Mental Environment, January 1, 2016.

Benfield, Kaid. “Why the Places We Live Make Us Happy.” CityLab, February 2, 2012. https://www.planetizen.com/node/88451/what-kind-commute-makes-people-happy.

Foucault Michel. Discipline and Punish The Birth of the Prison 1977 - 1995

Koskela, Hille. “‘Cam Era’ – the Contemporary Urban Panopticon,” Surveillance & Society 1(3): 292-313 http://www.surveillance-and-society.org

Montgomery, C. Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design. Doubleday Canada, 2013

Rajagopalan, Shruti, and Alexander Tabarrok. “LESSONS FROM GURGAON,” 07112014.

Roy and Alsayyad “Medieval Modernity: On Citizenship and Urbanism in a Global Era” April 2006.

Yardley. n.d. “The Gurgaon Story: A Mirror to India’s Growth.” NDTV.com. https://www.ndtv.com/gurgaon-news/the-gurgaon-story-a-mirror-to-indias-growth-458043.

Benfield, Kaid. “Why the Places We Live Make Us Happy.” CityLab, February 2, 2012. https://www.planetizen.com/node/88451/what-kind-commute-makes-people-happy.

Foucault Michel. Discipline and Punish The Birth of the Prison 1977 - 1995

Koskela, Hille. “‘Cam Era’ – the Contemporary Urban Panopticon,” Surveillance & Society 1(3): 292-313 http://www.surveillance-and-society.org

Montgomery, C. Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design. Doubleday Canada, 2013

Rajagopalan, Shruti, and Alexander Tabarrok. “LESSONS FROM GURGAON,” 07112014.

Roy and Alsayyad “Medieval Modernity: On Citizenship and Urbanism in a Global Era” April 2006.

Yardley. n.d. “The Gurgaon Story: A Mirror to India’s Growth.” NDTV.com. https://www.ndtv.com/gurgaon-news/the-gurgaon-story-a-mirror-to-indias-growth-458043.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

|

Ar. Avtar Bhalla is an architect and final year Masters student in urban design in Sushant School of Art and Architecture (Gurgaon, India). After completing his Bachelors degree in Architecture in 2015, he worked for a year as an architect in Jaipur, and pursued his Masters degree in urban design in 2016 to learn how not only architecture but urban design is such an important aspect of people’s daily life, creating strong impact on the mindset of the people. He mainly focuses on finding solutions to problems causing negative impacts on mental health of the people. He is interested in continuing the work on the urban design solutions using varied analytical tools curbing the issues of the cities for better mental health.

|

|

Ar. Sayna Anand is an architect and final year Masters student in urban design in Sushant School of Art and Architecture (Gurgaon, India). After completing her Bachelors degree in Architecture in 2015, she worked for a year as an architect in Jaipur, But the urge of getting closer to the people and their surroundings led her to pursue a Masters degree in urban design in 2016. She has a keen interest in exploring the effect of different types of surroundings on the psychology of the people. She believes urban design is an important tool to bring changes which can lead to happier cities and environments. She is interested in continuing research on related topics to bring a positive transformation of spaces in cities as an urban designer.

|