|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:13

|

ANALYSIS

Preventing Chronic Violence with Urban Rhythms

Emotional atmospheric manipulation for public mental health

Alan Waxman and Carl Belizaire

AWED, USA

AWED, USA

Key ideas for urban planning and design

How can designers and public health practitioners capture online social media in real time to address urban socio-spatial public health issues like violence? Trends in American violence reduction correspond closely with adoption of the internet. Analysis of geo-located smartphone technology and particular socio-spatial techniques that developed simultaneous to the drastic decrease in violence of the 1990s may guide research and deployment of evidence based psychosocial medicine and carry implications for addressing social dynamics on city streets.

How can designers and public health practitioners capture online social media in real time to address urban socio-spatial public health issues like violence? Trends in American violence reduction correspond closely with adoption of the internet. Analysis of geo-located smartphone technology and particular socio-spatial techniques that developed simultaneous to the drastic decrease in violence of the 1990s may guide research and deployment of evidence based psychosocial medicine and carry implications for addressing social dynamics on city streets.

Violence has a mental and spatial epidemiology: it is triggered by context and compounded social factors (1), associated with social networks, and maintained by lifestyle choices (2). Violence (sanctioned or otherwise) occurs in high rates in particular neighborhoods, institutional settings, and war zones (3,4,5,6). Because of this epidemiology, violence serves as a valuable lens for observing connections between environmental context and mental health.

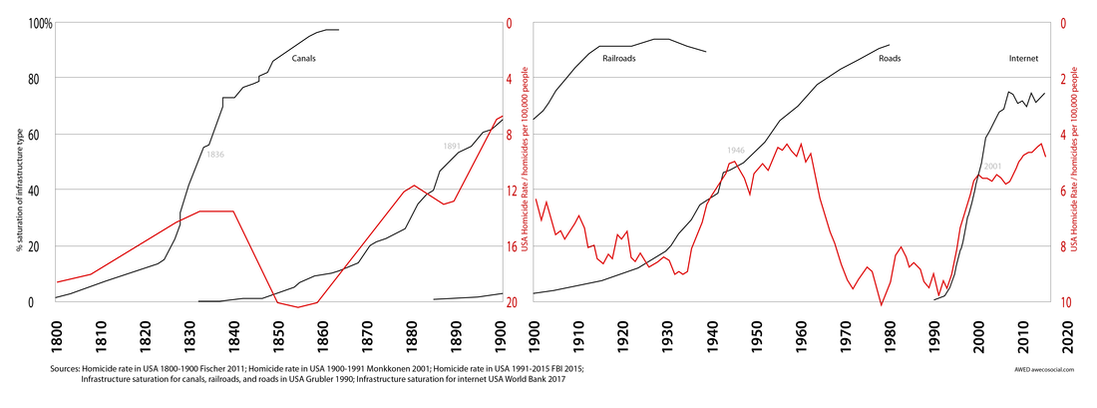

Urban systems materialize social hierarchy spatially along with technological change (7); effects of this hierarchy can be read in violence outcomes (8, 9). Figure 1 (produced by Waxman) shows the rising and falling homicide rate in the United States over the last two centuries, with correlated adoption rates of major infrastructural technologies. (10, 11, 12)

Urban systems materialize social hierarchy spatially along with technological change (7); effects of this hierarchy can be read in violence outcomes (8, 9). Figure 1 (produced by Waxman) shows the rising and falling homicide rate in the United States over the last two centuries, with correlated adoption rates of major infrastructural technologies. (10, 11, 12)

Figure 1: Homicide rate and infrastructure adoption in the USA 1800-2015

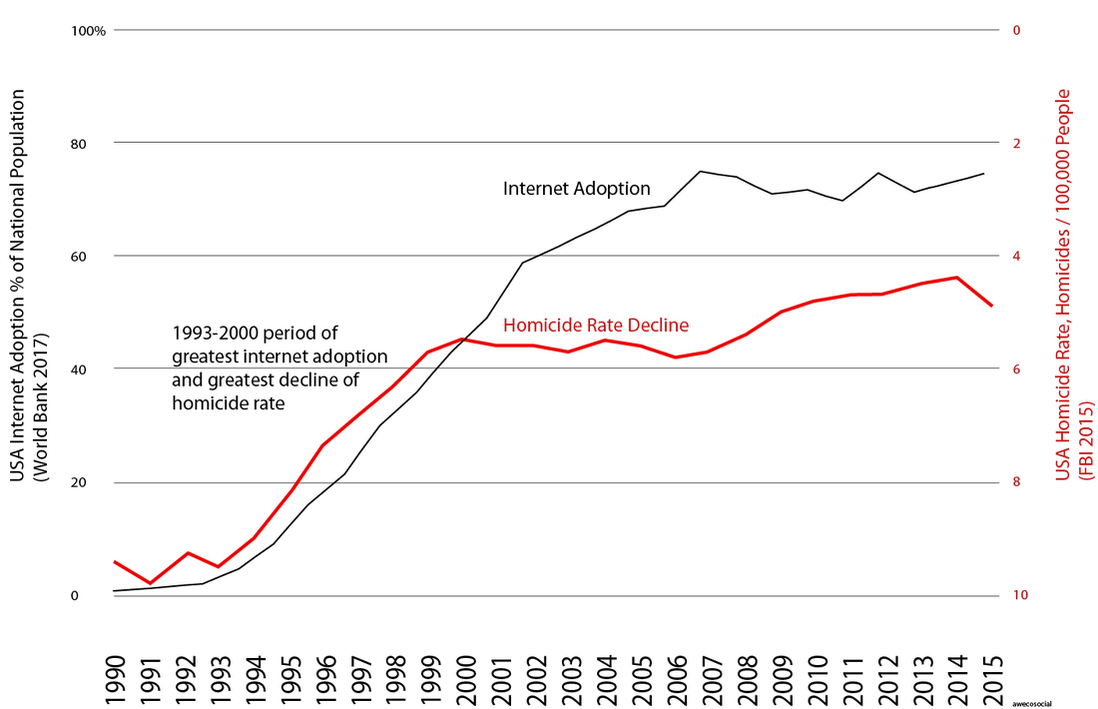

Reading changes in homicide rates becomes a way to consider how technological change and resulting urban systems are embodied by residents over time and space, especially when there is a very close correlation between the rise of a particular technology and corresponding change in homicide rate. See the chart below by Waxman of internet adoption and homicide rate in America. (13, 14)

Figure 2: Internet adoption and homicide rate in the Unites States 1990-2015

As practitioners in urban design, violence prevention, or public health, it is essential not just to identify which contextual changes (such as the adoption of the internet) coincide with radical decreases in violence, but also to identify how to design contextual change intentionally. This understanding is essential if we are to develop therapies to reduce an epidemic when it arises.

Much investment has recently been made into smartphone applications that allow users to intentionally change the emotional atmosphere of the physical environment by tapping into an internet-associated social media layer in physical space (15). Although smartphone applications have developed only in recent years, long after the decline in the homicide epidemic of the 1990s (16), they provide a useful vocabulary for the discussion of intentional emotional atmospheric manipulation through connection to social data. This utility is strengthened by considering smartphone applications in the context of a series of techniques that developed alongside the peak of the violence in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Mostly categorized as hip hop, these techniques of word play, audio synthesis, visual art, dance, and other elements, are known for their intentional emotional atmospheric manipulation of space(17).

Flexing: Changing The Intimate Environment

One form of intentional emotional atmospheric manipulation that developed in East Brooklyn in the 1990s, at exactly the same time as internet adoption, is "flexing”. Evolving from Jamaican dance hall, particularly the bruk up style, flexing allows artists to engage audiences through a set of movements that suspend disbelief, creating an extra-ordinary narrative space. Particular techniques are deployed to this end: “gliding” transforms the floor into a space of flight, “waving” turns the body into a means of demonstrating flow of time and energy; “isolation” gives the illusion of dismembering the body into distinct autonomous parts; “connecting” (also called “tutting”) renders the body into a kaleidoscopic geometry of sharp angles; “lyricism” conveys ideas through symbolic gesture; and “animation” describes using these techniques to create a narrative drama that onlookers understand and can enter into as a reality. In sum, flexing is a means to the creation and adjustment of an emotional environment with others. We single it out because the authors deploy the methodology experimentally in the violence prevention and public health design studio "Urban Rhythms,"(18) and because "flexing animation" works much like a smartphone application in its ability to allow users to embody and manipulate social data in real time (19).

In East Brooklyn in 1993, violence was at an all time high; in the district of Brownsville, the homicide rate was about 87 per 100,000 population, 3 times higher than the city average of 27 per 100,000 population, and 74 times higher than the city average today, which runs around 1 per 100,000 population (20). In the context of early 90's violence, flexing artists developed explosive and often dark imagery of guns and personal confrontation with death, deploying these techniques to engage audiences.

Many dancers learn to "animate" in order to intentionally change social dynamics in urban spaces. By deploying their technique, they aim to flow with the energy of the crowd and to overcome opponents in dance "battles." These battles are agonistic opportunities to work out a synthesis of diverse and rival elements. New dancers are immediately challenged to participate at battles. When defeated, they "go back to the lab" to improve, aiming to create elevated, seemingly "unreal," scenes where both the audience and rival dancers are irresistibly pulled into demonstrated narratives of pain, joy, or sorrow (Video 1).

Much investment has recently been made into smartphone applications that allow users to intentionally change the emotional atmosphere of the physical environment by tapping into an internet-associated social media layer in physical space (15). Although smartphone applications have developed only in recent years, long after the decline in the homicide epidemic of the 1990s (16), they provide a useful vocabulary for the discussion of intentional emotional atmospheric manipulation through connection to social data. This utility is strengthened by considering smartphone applications in the context of a series of techniques that developed alongside the peak of the violence in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Mostly categorized as hip hop, these techniques of word play, audio synthesis, visual art, dance, and other elements, are known for their intentional emotional atmospheric manipulation of space(17).

Flexing: Changing The Intimate Environment

One form of intentional emotional atmospheric manipulation that developed in East Brooklyn in the 1990s, at exactly the same time as internet adoption, is "flexing”. Evolving from Jamaican dance hall, particularly the bruk up style, flexing allows artists to engage audiences through a set of movements that suspend disbelief, creating an extra-ordinary narrative space. Particular techniques are deployed to this end: “gliding” transforms the floor into a space of flight, “waving” turns the body into a means of demonstrating flow of time and energy; “isolation” gives the illusion of dismembering the body into distinct autonomous parts; “connecting” (also called “tutting”) renders the body into a kaleidoscopic geometry of sharp angles; “lyricism” conveys ideas through symbolic gesture; and “animation” describes using these techniques to create a narrative drama that onlookers understand and can enter into as a reality. In sum, flexing is a means to the creation and adjustment of an emotional environment with others. We single it out because the authors deploy the methodology experimentally in the violence prevention and public health design studio "Urban Rhythms,"(18) and because "flexing animation" works much like a smartphone application in its ability to allow users to embody and manipulate social data in real time (19).

In East Brooklyn in 1993, violence was at an all time high; in the district of Brownsville, the homicide rate was about 87 per 100,000 population, 3 times higher than the city average of 27 per 100,000 population, and 74 times higher than the city average today, which runs around 1 per 100,000 population (20). In the context of early 90's violence, flexing artists developed explosive and often dark imagery of guns and personal confrontation with death, deploying these techniques to engage audiences.

Many dancers learn to "animate" in order to intentionally change social dynamics in urban spaces. By deploying their technique, they aim to flow with the energy of the crowd and to overcome opponents in dance "battles." These battles are agonistic opportunities to work out a synthesis of diverse and rival elements. New dancers are immediately challenged to participate at battles. When defeated, they "go back to the lab" to improve, aiming to create elevated, seemingly "unreal," scenes where both the audience and rival dancers are irresistibly pulled into demonstrated narratives of pain, joy, or sorrow (Video 1).

Video 1: Urban rhythms change patterns involving violence in shared urban spaces (5 mins 43 seconds)

Cipher: Coding Space for Mental Health

The result of the inter-subjective and dynamic feedback between dancers and the audience is that this "battle" creates an empowering setting in which the practitioners are directly "coding" the shared "social media," the shared emotional atmosphere of the space. In fact, the word used by practitioners to describe this stage of play and feedback is "cipher," literally meaning "code." The cipher is a space where the practitioners "code" the real time spectrum of emotional and signifying vibrations of their environment. In this respect, the cipher can be considered a key spatial dimension of "psychosocial medicine" because it seeks to "code" resonances in real time between the immaterial social media of the group and the physical embodiment of these social actors in a network.(21)

The flexing battle, and likewise, the Urban Rhythms studio, deploys this methodology much like a "hackathon"; except that most hackathons generally present a hierarchy of problem solving that works towards a particular goal (22), whereas the cipher, by contrast, can be defined more accurately, if metaphorically, like a "blockchain:" a peer-to-peer network in which all data is embedded directly in a dispersed participant network in dynamic exchange, updated in real time (23). Developments in blockchain technology and embedded, real time, psychosocial medicine suggests that ciphers can function as an embodied space of crypto-value that gains in value as participants enter more into the reality of their shared, embodied, narrative.

The result of the inter-subjective and dynamic feedback between dancers and the audience is that this "battle" creates an empowering setting in which the practitioners are directly "coding" the shared "social media," the shared emotional atmosphere of the space. In fact, the word used by practitioners to describe this stage of play and feedback is "cipher," literally meaning "code." The cipher is a space where the practitioners "code" the real time spectrum of emotional and signifying vibrations of their environment. In this respect, the cipher can be considered a key spatial dimension of "psychosocial medicine" because it seeks to "code" resonances in real time between the immaterial social media of the group and the physical embodiment of these social actors in a network.(21)

The flexing battle, and likewise, the Urban Rhythms studio, deploys this methodology much like a "hackathon"; except that most hackathons generally present a hierarchy of problem solving that works towards a particular goal (22), whereas the cipher, by contrast, can be defined more accurately, if metaphorically, like a "blockchain:" a peer-to-peer network in which all data is embedded directly in a dispersed participant network in dynamic exchange, updated in real time (23). Developments in blockchain technology and embedded, real time, psychosocial medicine suggests that ciphers can function as an embodied space of crypto-value that gains in value as participants enter more into the reality of their shared, embodied, narrative.

A recent performance entitled "We are the environment" at the Mark Morris Dance Group demonstrates how the cipher is used to adapt the shared emotional atmosphere in a network:

An audience of about forty surrounds four pairs of dancers. As music begins, the first pair, Kester "Flexx" Estephane and Anthony "Laiden" John, hold up a sign, "fear." Proceeding to the center of the circle, they improvise within the flexing vocabulary the emotion of "fear." As they gesticulate in graphic detail, another pair rises to join them. Brian "Impact" Rodriguez and Hannah Da Silva present "anger." Bristling with movements representative of guns and fists, they attack Estephane and John, overcoming "fear" through "anger." A couple follows them; Joshua "Sage" Morales and Risa Kunita; bearing movements of "love." These two embrace Rodriguez and Da Silva, gliding into center stage. Note that these encounters are improvisational and it is the test of the artists to actually change the shared emotional atmosphere presented by the previous dancers. Alan Waxman and Carl Belizaire then demonstrate "healing" as Waxman appears increasingly ill and Belizaire acts as confident doctor. When Waxman collapses in a coughing fit, Belizaire begins to summon the energy of "healing" from the music, capturing the beat with body waves, reanimating Waxman. The pair then spreads the energy to the other six dancers and, one by one, the dancers engage the crowd, pulling them into one continuously moving rhythm in form. The pattern of movement developed through the narrative catches from person to person, spreading throughout the room. Audience members who came to a performance have become the performance.

An audience of about forty surrounds four pairs of dancers. As music begins, the first pair, Kester "Flexx" Estephane and Anthony "Laiden" John, hold up a sign, "fear." Proceeding to the center of the circle, they improvise within the flexing vocabulary the emotion of "fear." As they gesticulate in graphic detail, another pair rises to join them. Brian "Impact" Rodriguez and Hannah Da Silva present "anger." Bristling with movements representative of guns and fists, they attack Estephane and John, overcoming "fear" through "anger." A couple follows them; Joshua "Sage" Morales and Risa Kunita; bearing movements of "love." These two embrace Rodriguez and Da Silva, gliding into center stage. Note that these encounters are improvisational and it is the test of the artists to actually change the shared emotional atmosphere presented by the previous dancers. Alan Waxman and Carl Belizaire then demonstrate "healing" as Waxman appears increasingly ill and Belizaire acts as confident doctor. When Waxman collapses in a coughing fit, Belizaire begins to summon the energy of "healing" from the music, capturing the beat with body waves, reanimating Waxman. The pair then spreads the energy to the other six dancers and, one by one, the dancers engage the crowd, pulling them into one continuously moving rhythm in form. The pattern of movement developed through the narrative catches from person to person, spreading throughout the room. Audience members who came to a performance have become the performance.

Decreasing Violence in the Inner City

Over the last 10 years, extremely popular geolocation-based apps like Google Maps, Uber, AirBnB, and Tinder have allowed for personal real-time negotiation of urban spaces by allowing users to tap into a "social media layer" in physical urban territory. This has capitalized on a desire to move from couch and car driver's seat to cafes and sidewalks (24). These apps were developed largely in the context of the suburbs in car-based Silicon Valley on the West Coast and have coincided with nationwide trends of people moving from car based areas to walkable urban neighborhoods (25, 26).

"Flexing animation" and other forms of emotional atmospheric manipulation, on the other hand, were invented in inner cities, not with the outcome of bringing people out of their cars for purchases on the street, but rather for actively changing the way people on the street, and in intimate settings in general, feel and act. If "flexing animation" is described as an application, it is one in which the smartphone has vanished into the body: the practitioner directly taps into the shared social environment, makes it tangible, and manipulates it.

Over the past twenty-five years there has been an increasing recognition in medical research of the relevance of mind body therapies (27), particularly those studies that show changes in outcomes of disease treatment. The Urban Rhythms studios provide an example of active change in urban socio-spatial patterns. In considering the relationship of mind and body on an urban scale it essential to consider how social media becomes embodied, and also how it can be therapeutically manipulated.

The rise of internet and smartphone applications provide a mechanical means to locate the adoption of media on the street. There is increasing convergence of social media and public space management in the deployment of social media imaging and data to locate offenders of the state (28), for example, or to streamline management of large corporate-controlled pseudo-public spaces (29). Even without direct management of spaces in the hands of a single state or corporate actor, applications like Uber, AirBnb, and Tinder have radically altered the way people use public and private spaces (30). It remains to be seen if these changes may actually usher in an increase in violence overall. If the graph of trends over the past 200 years, above, is an indicator, it is likely there will be a general rise in homicide rate in the United States in the next decade.

"Flexing animation" developed in contexts where high violence rates drastically fell in the first years of internet adoption. At that time, ciphers were deployed as this particular therapy for adapting the emotional atmosphere of the street was developed in situ. By the time geo-located smartphone apps were deployed in recent years and more market capital became invested in the inner city, violence rates had already fallen. This implies that when compared to capital-driven application and smartphone products, innovative cipher techniques of the 1990s may more relevantly capture social media of the internet in street space for violence prevention. We can even infer that the cipher may represent a future of smartphone applications that goes beyond the mechanics of the phone itself to directly consider the body and the street.

As practitioners of urban design for public health it is essential to understand what innovative techniques have corresponded with drastic changes to human experience on the street with violence as a key indicator. We must learn how to adapt these techniques into evidence-based therapies relevant for addressing violence on a location basis. “Flexing animation,” and other spatial coding arts that developed in this context of space and time, provide us with the basis for these adaptive therapies.

References

1)Krieger, Nancy, "Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective" International Journal of Epidemiology 2001

2) "Make the Case: Violence is Preventable" Prevention Institute, 2017.

3) Milgram, Stanley "Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View", 1974.

4) “Neighborhoods and Violent Crime” Office of Housing and Urban Development, 2016.

5) “Violence and Socioeconomic Status Fact Sheet” American Psychological Association, 2017.

6) “The Human Security Report” Human Security Report Project 2005.

7) Grubler, Arnulf, The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures 1990.

8) Flannery, Daniel, Social Contagion of Violence. Columbia Public Law Research Paper No. 06-126, 2007.

9)Cure Violence. Violence As a Health Issue 2017.

10) Grubler, Arnulf, The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures 1990.

11)Fischer, Claude, "A Crime Puzzle" 2011.

12)Monkkonen, Eric H. Murder in New York City, 2001.

13)FBI homicide rate USA

14)World Bank 2017

15) Smith, Aaron, Record shares of Americans now own smartphones, have home broadband. Pew Research 2017.

16) Bakker, D., Kazantzis, N., Rickwood, D., & Rickard, N. (2016). Mental Health Smartphone Apps: Review and Evidence-Based Recommendations for Future Developments. JMIR Mental Health, 3(1), e7. http://doi.org/10.2196/mental.4984

17) "Droppin Science: Critical Essays on Rap Music and Hop Hop Culture" ed William Eric Perkins, 1996

2016

18)Mark Morris Dance Group, Allegra Oxborough ed, Urban Rhythms program description, https://vimeo.com/159002345

19) Waxman, Alan, A New Kind of Hospital Room. Urban Health Design Forum 2017.

20) NYPD.gov crime statistics

21) DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES National Institutes of Health Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at NIH 2001 Psychosocial medicine definition p5

22) Leckart, Steven, The Hackathon Is On: Pitching and Programming the Next Killer App, 2012.

23) Bryant, Meg, Blockchain may be healthcare's answer to interoperability, data security, 2016.

24) Wall, Quinton, Requiem For The App Revolution, Techcrunch 2015.

25)Piiparinen, Richey, The Persistence of Failed History: 'White Infill' as the new 'White Flight? New Geography, 2013.

26) Yee, Vivian, Gentrification in a Brooklyn Neighborhood Forces Residents to Move On. New York Times, 2015.

27)NIH Research Resource for Systematic Review of Complementary and Integrative Health, 2017.

28) Chin, Josh, and Liza Lin, China’s All-Seeing Surveillance State Is Reading Its Citizens’ Faces. Wall Street Journal June 26, 2017.

29) Boysen, Ryan, Hudson Yards’ Smart City Initiatives Could Provide Glimpse Of NYC’s Future. BisNow, February 22, 2016.

30)Penn, Joanna, and John Wihbey, Uber, Airbnb and consequences of the sharing economy: Research roundup. Journalist’s Resource, June 3, 2016

Over the last 10 years, extremely popular geolocation-based apps like Google Maps, Uber, AirBnB, and Tinder have allowed for personal real-time negotiation of urban spaces by allowing users to tap into a "social media layer" in physical urban territory. This has capitalized on a desire to move from couch and car driver's seat to cafes and sidewalks (24). These apps were developed largely in the context of the suburbs in car-based Silicon Valley on the West Coast and have coincided with nationwide trends of people moving from car based areas to walkable urban neighborhoods (25, 26).

"Flexing animation" and other forms of emotional atmospheric manipulation, on the other hand, were invented in inner cities, not with the outcome of bringing people out of their cars for purchases on the street, but rather for actively changing the way people on the street, and in intimate settings in general, feel and act. If "flexing animation" is described as an application, it is one in which the smartphone has vanished into the body: the practitioner directly taps into the shared social environment, makes it tangible, and manipulates it.

Over the past twenty-five years there has been an increasing recognition in medical research of the relevance of mind body therapies (27), particularly those studies that show changes in outcomes of disease treatment. The Urban Rhythms studios provide an example of active change in urban socio-spatial patterns. In considering the relationship of mind and body on an urban scale it essential to consider how social media becomes embodied, and also how it can be therapeutically manipulated.

The rise of internet and smartphone applications provide a mechanical means to locate the adoption of media on the street. There is increasing convergence of social media and public space management in the deployment of social media imaging and data to locate offenders of the state (28), for example, or to streamline management of large corporate-controlled pseudo-public spaces (29). Even without direct management of spaces in the hands of a single state or corporate actor, applications like Uber, AirBnb, and Tinder have radically altered the way people use public and private spaces (30). It remains to be seen if these changes may actually usher in an increase in violence overall. If the graph of trends over the past 200 years, above, is an indicator, it is likely there will be a general rise in homicide rate in the United States in the next decade.

"Flexing animation" developed in contexts where high violence rates drastically fell in the first years of internet adoption. At that time, ciphers were deployed as this particular therapy for adapting the emotional atmosphere of the street was developed in situ. By the time geo-located smartphone apps were deployed in recent years and more market capital became invested in the inner city, violence rates had already fallen. This implies that when compared to capital-driven application and smartphone products, innovative cipher techniques of the 1990s may more relevantly capture social media of the internet in street space for violence prevention. We can even infer that the cipher may represent a future of smartphone applications that goes beyond the mechanics of the phone itself to directly consider the body and the street.

As practitioners of urban design for public health it is essential to understand what innovative techniques have corresponded with drastic changes to human experience on the street with violence as a key indicator. We must learn how to adapt these techniques into evidence-based therapies relevant for addressing violence on a location basis. “Flexing animation,” and other spatial coding arts that developed in this context of space and time, provide us with the basis for these adaptive therapies.

References

1)Krieger, Nancy, "Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective" International Journal of Epidemiology 2001

2) "Make the Case: Violence is Preventable" Prevention Institute, 2017.

3) Milgram, Stanley "Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View", 1974.

4) “Neighborhoods and Violent Crime” Office of Housing and Urban Development, 2016.

5) “Violence and Socioeconomic Status Fact Sheet” American Psychological Association, 2017.

6) “The Human Security Report” Human Security Report Project 2005.

7) Grubler, Arnulf, The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures 1990.

8) Flannery, Daniel, Social Contagion of Violence. Columbia Public Law Research Paper No. 06-126, 2007.

9)Cure Violence. Violence As a Health Issue 2017.

10) Grubler, Arnulf, The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures 1990.

11)Fischer, Claude, "A Crime Puzzle" 2011.

12)Monkkonen, Eric H. Murder in New York City, 2001.

13)FBI homicide rate USA

14)World Bank 2017

15) Smith, Aaron, Record shares of Americans now own smartphones, have home broadband. Pew Research 2017.

16) Bakker, D., Kazantzis, N., Rickwood, D., & Rickard, N. (2016). Mental Health Smartphone Apps: Review and Evidence-Based Recommendations for Future Developments. JMIR Mental Health, 3(1), e7. http://doi.org/10.2196/mental.4984

17) "Droppin Science: Critical Essays on Rap Music and Hop Hop Culture" ed William Eric Perkins, 1996

2016

18)Mark Morris Dance Group, Allegra Oxborough ed, Urban Rhythms program description, https://vimeo.com/159002345

19) Waxman, Alan, A New Kind of Hospital Room. Urban Health Design Forum 2017.

20) NYPD.gov crime statistics

21) DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES National Institutes of Health Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at NIH 2001 Psychosocial medicine definition p5

22) Leckart, Steven, The Hackathon Is On: Pitching and Programming the Next Killer App, 2012.

23) Bryant, Meg, Blockchain may be healthcare's answer to interoperability, data security, 2016.

24) Wall, Quinton, Requiem For The App Revolution, Techcrunch 2015.

25)Piiparinen, Richey, The Persistence of Failed History: 'White Infill' as the new 'White Flight? New Geography, 2013.

26) Yee, Vivian, Gentrification in a Brooklyn Neighborhood Forces Residents to Move On. New York Times, 2015.

27)NIH Research Resource for Systematic Review of Complementary and Integrative Health, 2017.

28) Chin, Josh, and Liza Lin, China’s All-Seeing Surveillance State Is Reading Its Citizens’ Faces. Wall Street Journal June 26, 2017.

29) Boysen, Ryan, Hudson Yards’ Smart City Initiatives Could Provide Glimpse Of NYC’s Future. BisNow, February 22, 2016.

30)Penn, Joanna, and John Wihbey, Uber, Airbnb and consequences of the sharing economy: Research roundup. Journalist’s Resource, June 3, 2016

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS

About the Authors

|

Alan Waxman MLA creates ecosocial design for health equity and cultural resiliency. By operating in locations of fragility in space and time, he aims to bring people together to reopen critical narratives. His current Urban Rhythms studios with Mark Morris Dance Group, the Center For Court Innovation, and other partners, assess urban patterns by way of participatory engagement; setting up emic spectrums of data derived from meaning for cultural insiders. Resident participants, those who have the most to gain and the most to lose, collaborate to make real time interventions through events, dance, and environmental change. As "Neighborhood Doctor," Waxman deploys ecosocial design in Brownsville, Brooklyn NY and Kyoto, Japan, where he serves as an instructor with the University of Oregon in their Myoshinji Zen temple based urban design program. In 2015, he and Sang Cho produced New York City's first Health Impact Assessment with a group of elder residents in Brownsville. Working on projects primarily for NYC Parks, Waxman works for Quennell Rothschild and Partners, a leading landscape architecture firm for public space design. He is an inaugural Forefront Fellow with the Urban Design Forum in New York City. Waxman led Harvard’s Project Link Program from 2013-2014 for under-served youth, performing a youth led urban design charrette for a critical transportation artery in Malden Massachusetts. He is co-founder of Real Time Health Mapping, a trans-disciplinary effort to bring social and environmental data streams into hospital IT to create a model for low cost, high quality chronic disease treatment based in long term community engagement. He served on the organizing committee for the 2014 Health Equity and Leadership Conference (HKS, HSPH, HGSD, College) aimed at curating closer relationships between Universities and community groups in Boston neighborhoods, particularly those at high risk for chronic disease. In 2012, with Nikola Bojic, Waxman designed and built Hangzhou’s Sinking Gardens, positioning a displaced community at the fore-front of Hangzhou’s contemporary public art scene. He has taught English as a second language in Kyoto, Japan, at the University of Oregon, and tutored high school in the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Waxman is originally from the Pacific Coast.

|

|

Carl Belizaire is a professor, dance performer, and entrepreneur. He teaches math at Baruch College where he is a graduate in Entrepreneurship/Small Business Management. Carl spent years pursuing his love for dance and has built himself an extensive background through the performing world. Self taught in "Flexing," which originated from the Jamaican dance style "Bruk-Up" he has performed on the television station BCAT on the program "Flex in Brooklyn." The technique incorporates waving, gliding, pausing (pop locking), connecting (tutting), animation, lyricism, storytelling and musicality. Carl's mastery of Flexing has allowed him to go professional and he has since worked as an instructor at Sports and Arts in School Foundation, an afterschool program geared towards enriching the lives of youths though academics and extracurricular activities. Carl is featured in films such as "Girl Walk All Day," produced by Jacob Krupnick, "Attitude 3" produced by Isaac Goodwine, the documentary "Flex is Kings" produced by Diedre Schoo, and the opera "Kwaidan" by Yara Travieso and Jerome Begin. In addition, he manages his own group of dancers called Street's Finest and has performed at the WIld Project and the Brooklyn Museum. Carl has written a number of books on motivation, and when asked what drives him, he responds, "my desire to succeed in life and be able to support my family."

|

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS