|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:4

|

Urban design and mental health in Tokyo: a city case study

Layla McCay (1,2), Emily Suzuki (2) and Anna Chang (3)

(1) Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, UK and Japan

(2) Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Japan

(3) Southern California Institute of Architecture, USA

(1) Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, UK and Japan

(2) Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Japan

(3) Southern California Institute of Architecture, USA

A UD/MH city case study examines how a particular city applies the key principles of urban design for good population mental health, and identifies opportunities for this city and lessons for other cities.

- City case studies currently underway: Wroclaw (Poland), Montreal (Canada), Morristown (USA).

- If you wish to conduct a city case study, learn more here.

6 Urban planning/design lessons from Tokyo for better public mental health

- Streetparks: Empower and incentivise residents to install nature everywhere (and easily access out of town nature)

- Superblocks: Nudge vehicles into larger streets to prioritise active transport, social streetlife, green space etc.

- Active transport: The affordable, efficient, reliable and convenient choice

- Social exercise: Easy access and changing/storage facilities

- Interior placemaking: popular indoor spaces like shopping malls can be green, active, and pro-social like a high street

- Suicide-prevention design: Innovative design interventions include blue light and nature images in train stations

5 Urban planning/design steps to help improve Tokyo’s public mental health

- Increase awareness: Urban planners and designers need to appreciate urban design and mental health opportunities

- Seize the cycling opportunity: remove workplace barriers to instill bike commuting; infrastructure will follow demand

- Harness neglected waterways: for walking, sports, socialising and relaxation

- Social interaction: This should be at the heart of more public space design

- Optimise the workplace: Long working hours means the importance of commute and office design to promote better mental health

Introduction

The World Health Organisation defines mental health as: “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.” This definition is relevant for urban designers because it also reflects key components of a thriving, resilient urban population. Key urban design factors that can affect mental health include: access to natural (green and blue) spaces (Roe 2016, Gascon et al 2015), facilitating physical activity (Morgan et al 2013), pro-social activity (Francis et al 2012), safety (including wayfinding, crime, and traffic), and sleep quality (Clark et al 2006, Litman 2016).

Overview of mental health in Tokyo

Tokyo has a complex relationship with mental health. There is a lack of universally understood term: 'mental health' is often taken to mean mental illness (in Tokyo, a person with a mental illness is sometimes referred to by the abbreviation 'men-hel') which can make it complicated to discuss mental health promotion. It is hard to identify Tokyo-specific mental health statistics. The World Mental Health Japan survey conducted mental health assessments with 4,000 people in Japan, and found the lifetime prevalence of common mental illnesses to be around 1 in 5 people, which is lower than in many Western countries (Ishikawa et al, 2016). However, mental disorders are also the second greatest cause of severe role impairment of all chronic health problems in Japan (approximately 2.6 million people), and mental illness is considered to account for nearly a quarter of all-cause disease burden in Japan (Health Japan, 2016). The World Mental Health survey measured Japanese people’s lifetime risk of anxiety disorders to be 8.1%, substance use disorders (largely alcohol) 7.4%, and mood disorders (largely depression) 6.5%. Men were more likely to have a mental disorder in their lifetime, but women and younger people were more likely to have persistent disorders.

In addition, Tokyo has some country-specific mental health challenges. Mental health problems are subject to profound stigma. Almost universally long working hours have led to a more restricted leisure culture than in some other cities. In a country with high levels of overtime, Karoshi (death by overwork) is associated with very high stress levels and low food intake, leading to heart attack, stroke or suicide. The evidence on causality and prevalence is still incomplete, but karoshi is often in the news. Japan is known for high suicide rates, though this is improving; however, figures vary but Japan still has the 6th highest suicide rate in the world (18.7 per 100,000 people in 2013, OECD). Suicide has a complex mix of drivers in Japan, from depression to a tradition of ‘honourable suicide’ following unemployment, financial problems, or causing a burden for family members. Nearly one million people each year experience Hikkikomori, acute social withdrawal typified by a young person not leaving their home for more than six months, with a lifetime prevalence of 1.2% (Koyama et al, 2010). Finally, some people who were affected by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011 have developed post-disaster mental health problems, and Tokyo’s population lives in recognition that a large earthquake could occur at any time.

The proportion of people with mental disorders who receive diagnosis and treatment in Japan is lower than in many Western countries, likely associated with ongoing stigma, a reluctance to divulge mental health problems, and low uptake of psychiatry careers. Just 1 in 5 people with mental health problems seek formal treatment (Ishikawa et al, 2016).

The evolution of urban planning and design in Tokyo

Tokyo is often considered a city, but it is in fact a metropolitan prefecture (region) comprising 23 special wards, each governed as separate cities, plus 26 more cities, 5 towns, and 8 villages, all governed separately (with national and Tokyo Metropolitan Government influence), creating a complex picture in terms of urban planning. The city has a population of over 13 million, and the metropolitan area extends to a population of 36 million, the most populous in the world (World Population Review, 2017). The centre has a density of 15,187 people per square kilometer, much less than Manhattan (27,000) and Paris (21,000).

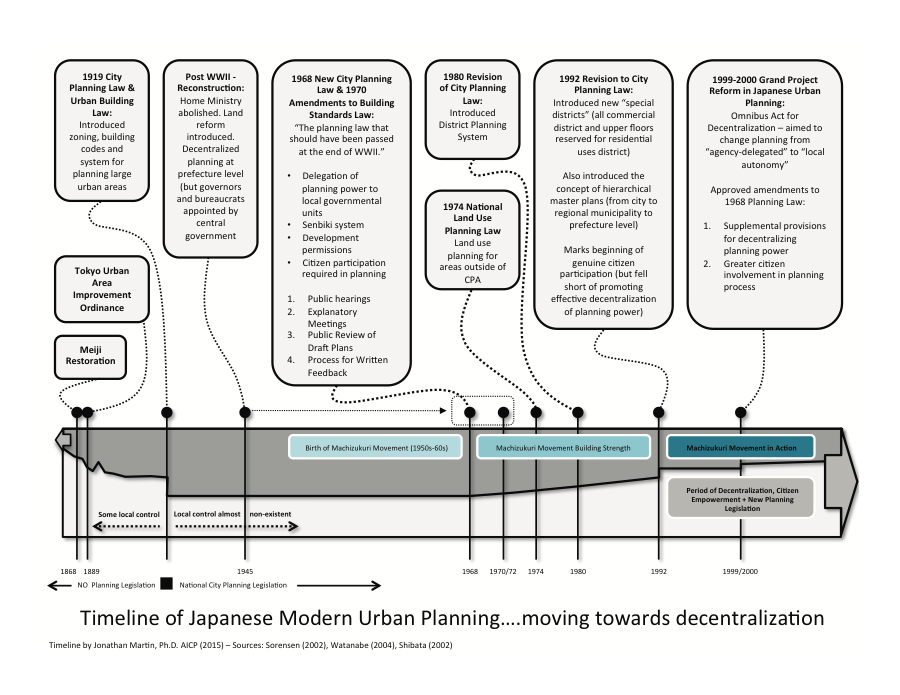

Tokyo’s urban planning history can be characterised by a cycle of city destruction and rebuilding. Fires, earthquakes and war have driven Tokyo’s planning efforts and ever-changing cityscapes, particularly since the Great Ginza Fire of 1872, just after Tokyo became the capital of Japan. Indeed, the Great Ginza Fire precipitated the Meiji Government’s first modern urban planning project, rebuilding to create a ‘fireproof’ city that incorporated a brick quarter and several parks. This led to the establishment of the Tokyo Town Planning Ordinance in 1888, then the 1919 Planning Law, and the birth of toshi keikaku/modern urban planning, in Tokyo, establishing top-down planning systems. The next big reconstruction project followed the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, and resulted in the development of the city’s extensive rail system. Then post-WWII, further rebuilding was necessary following war damage. The 1968 City Planning Law delegated more planning powers to the local level (its revision in 1980 was the first to explicitly include consideration of quality of life). Over the next few decades came a surge in population and industry, and along with that, a succession of laws around parks and green spaces, roads and railways, crowding and pollution. Many of Tokyo's rivers were sent underground or diverted, and canals and aqueducts were installed. With soaring house prices, residents increasingly moved to the suburbs, leading to ‘doughnutisation’ or reduced populations in the centre of the Tokyo prefecture, with mainly home owners (often older people) remaining in the centre. Since the ‘bubble economy’ burst in the 1990s, central housing has become more affordable again, and some younger people have returned to live in the city centre.

The World Health Organisation defines mental health as: “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.” This definition is relevant for urban designers because it also reflects key components of a thriving, resilient urban population. Key urban design factors that can affect mental health include: access to natural (green and blue) spaces (Roe 2016, Gascon et al 2015), facilitating physical activity (Morgan et al 2013), pro-social activity (Francis et al 2012), safety (including wayfinding, crime, and traffic), and sleep quality (Clark et al 2006, Litman 2016).

Overview of mental health in Tokyo

Tokyo has a complex relationship with mental health. There is a lack of universally understood term: 'mental health' is often taken to mean mental illness (in Tokyo, a person with a mental illness is sometimes referred to by the abbreviation 'men-hel') which can make it complicated to discuss mental health promotion. It is hard to identify Tokyo-specific mental health statistics. The World Mental Health Japan survey conducted mental health assessments with 4,000 people in Japan, and found the lifetime prevalence of common mental illnesses to be around 1 in 5 people, which is lower than in many Western countries (Ishikawa et al, 2016). However, mental disorders are also the second greatest cause of severe role impairment of all chronic health problems in Japan (approximately 2.6 million people), and mental illness is considered to account for nearly a quarter of all-cause disease burden in Japan (Health Japan, 2016). The World Mental Health survey measured Japanese people’s lifetime risk of anxiety disorders to be 8.1%, substance use disorders (largely alcohol) 7.4%, and mood disorders (largely depression) 6.5%. Men were more likely to have a mental disorder in their lifetime, but women and younger people were more likely to have persistent disorders.

In addition, Tokyo has some country-specific mental health challenges. Mental health problems are subject to profound stigma. Almost universally long working hours have led to a more restricted leisure culture than in some other cities. In a country with high levels of overtime, Karoshi (death by overwork) is associated with very high stress levels and low food intake, leading to heart attack, stroke or suicide. The evidence on causality and prevalence is still incomplete, but karoshi is often in the news. Japan is known for high suicide rates, though this is improving; however, figures vary but Japan still has the 6th highest suicide rate in the world (18.7 per 100,000 people in 2013, OECD). Suicide has a complex mix of drivers in Japan, from depression to a tradition of ‘honourable suicide’ following unemployment, financial problems, or causing a burden for family members. Nearly one million people each year experience Hikkikomori, acute social withdrawal typified by a young person not leaving their home for more than six months, with a lifetime prevalence of 1.2% (Koyama et al, 2010). Finally, some people who were affected by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011 have developed post-disaster mental health problems, and Tokyo’s population lives in recognition that a large earthquake could occur at any time.

The proportion of people with mental disorders who receive diagnosis and treatment in Japan is lower than in many Western countries, likely associated with ongoing stigma, a reluctance to divulge mental health problems, and low uptake of psychiatry careers. Just 1 in 5 people with mental health problems seek formal treatment (Ishikawa et al, 2016).

The evolution of urban planning and design in Tokyo

Tokyo is often considered a city, but it is in fact a metropolitan prefecture (region) comprising 23 special wards, each governed as separate cities, plus 26 more cities, 5 towns, and 8 villages, all governed separately (with national and Tokyo Metropolitan Government influence), creating a complex picture in terms of urban planning. The city has a population of over 13 million, and the metropolitan area extends to a population of 36 million, the most populous in the world (World Population Review, 2017). The centre has a density of 15,187 people per square kilometer, much less than Manhattan (27,000) and Paris (21,000).

Tokyo’s urban planning history can be characterised by a cycle of city destruction and rebuilding. Fires, earthquakes and war have driven Tokyo’s planning efforts and ever-changing cityscapes, particularly since the Great Ginza Fire of 1872, just after Tokyo became the capital of Japan. Indeed, the Great Ginza Fire precipitated the Meiji Government’s first modern urban planning project, rebuilding to create a ‘fireproof’ city that incorporated a brick quarter and several parks. This led to the establishment of the Tokyo Town Planning Ordinance in 1888, then the 1919 Planning Law, and the birth of toshi keikaku/modern urban planning, in Tokyo, establishing top-down planning systems. The next big reconstruction project followed the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, and resulted in the development of the city’s extensive rail system. Then post-WWII, further rebuilding was necessary following war damage. The 1968 City Planning Law delegated more planning powers to the local level (its revision in 1980 was the first to explicitly include consideration of quality of life). Over the next few decades came a surge in population and industry, and along with that, a succession of laws around parks and green spaces, roads and railways, crowding and pollution. Many of Tokyo's rivers were sent underground or diverted, and canals and aqueducts were installed. With soaring house prices, residents increasingly moved to the suburbs, leading to ‘doughnutisation’ or reduced populations in the centre of the Tokyo prefecture, with mainly home owners (often older people) remaining in the centre. Since the ‘bubble economy’ burst in the 1990s, central housing has become more affordable again, and some younger people have returned to live in the city centre.

Figure 1: Timeline of Japanese modern urban planning

Methods

Literature review

A search was conducted on the Tokyo Metropolitan Government website to identify relevant policy documents. These were retrieved and assessed, and relevant sections were identified and extracted. Further policies mentioned by interviewees were also examined.

Interviews

Eleven Tokyo-based academics, public health specialists, mental health specialists, urban planners, urban designers, developers and architects were identified by snowball sampling. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with each person in either English or in Japanese with English translation. Each subject was asked about what they considered to be urban design factors that support good mental health, the priority given to mental health in urban design policies and plans, and barriers to prioritisation using the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health protocol.

Literature review

A search was conducted on the Tokyo Metropolitan Government website to identify relevant policy documents. These were retrieved and assessed, and relevant sections were identified and extracted. Further policies mentioned by interviewees were also examined.

Interviews

Eleven Tokyo-based academics, public health specialists, mental health specialists, urban planners, urban designers, developers and architects were identified by snowball sampling. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with each person in either English or in Japanese with English translation. Each subject was asked about what they considered to be urban design factors that support good mental health, the priority given to mental health in urban design policies and plans, and barriers to prioritisation using the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health protocol.

Tokyo street scene. Picture by Mai Kobuchi.

Results

‘Compared with other Asian countries whose population density is quite high, Tokyo is a less stressful city. I don’t think this is realized by a particular architect but by well-organized city planning. This city planning is unique to Japan.’ – Urban planner

Tokyo’s urban policies with the potential to impact mental health

‘Health is always the most important topic in urban planning. When we had the Meiji Restoration, a priority topic was health. We needed more sunshine to improve people’s health, which can be realized by making more windows. Once we regulated it, we could get enough windows.’ – Urban Planner

At a national level, Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism has set five goals, which may be relevant to urban design for mental health:

In a city governed by complex laws and policies, Tokyo, prioritisation of health in general has been important (though explicit focus on the mental aspect of health has been more limited). Japan’s National Spatial Planning Act, Capital Regional Plan (2009) expects the Tokyo area to fulfill various roles in the 21st century including: being a beautiful area where 42 million people can live comfortably; conservation and creation of a good environment; and disaster-proofing to provide safety. While Tokyo Metropolitan Government manages certain Tokyo-wide policies, which will be discussed in this paper, in general, urban policies vary substantially within the wider Tokyo prefecture, and there is scope for individual case studies of cities within Tokyo metropolis.

Tokyo has six stated goals for urban planning. Relevant for mental health, these include: restoration of green and blue spaces; and creating a city where people can live comfortably, safely, and with peace of mind. Resident consultation and active participation in the planning process is important to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, and the trend, particularly in the past decade, has been decentralisation of city planning.

Despite the proliferation of urban policies that recognise health, many of the architects, urban planners and developers interviewed reported that they were not familiar with specific laws, policies or guidelines that they were obliged or encouraged to follow that explicitly included health promotion for the population, though an exception is for older people.

‘The government does not issue policies about health for urban planners or architects, except for particular cases, such as the size of rooms in group homes for people with dementia, or the percentage of green space for developments. Architects are trained to build good environments; there is no effort to regulate them once they have qualified.’ – Developer

‘Most of the guidelines that specifically mention health are aiming for making comfortable environment for elderly people. For example, in Sugamo, which is called “Harajuku for the elderly people,” the government spent money to make the area walkable and barrier-free.’ – Urban designer

Opinions about the environmental determinants of mental health

Interviewees identified factors within the built environment that they personally considered to be associated with mental health in Japan: beauty, nature, opportunities for creativity, social connections, opportunities to contribute to the community, access to healthcare, safety, and confidence that the city is well-managed, including efficient, reliable transportation.

Access to nature: green and blue places

One of the main ways in which Tokyo’s urban design seeks to promote better mental health is by increasing citizens’ access to green space. In the Edo period, Tokyo was filled with green spaces and waterfront parks. However, with industrialisation, much of this was lost. Tokyo policies explicitly recognise the health benefits of green space:

‘Greenery in urban areas brings pleasant and comfortable features to the lifestyles of residents’ and ‘greenery brings comfort to the human spirit’. (Basic Policies for the 10-year Project for Green Tokyo, TMG 2007).

The concept of access to green space as a factor that promotes good mental health is generally recognised, particularly in the context of appreciating nature and beauty:

‘We try to make more natural things in public space by planting trees’ – Urban Planner

‘Plants are a way to improve happiness’ – Think Tank academic

‘Japanese people have this ability to screen out any ugliness and chaos, just ignore it and focus on what is beautiful’ – Health company employee

‘Japanese people care about beauty and appreciate nature and how it can be seen in the changing seasons'– Think Tank academic

In addition to having several public parks, Tokyo has a range of large, landscaped parks that can be visited for a small fee. However, the opportunities and challenges of integrating further greenery into the Tokyo cityscape, while considered congruous, may be challenging in practice, given the existing development of the city.

‘Part of Japan’s culture is having small pieces of nature around you: plants and water. This is part of the concept behind bonsai trees: the ability to feel like you are in a forest when you are in a tiny apartment’ – Policy specialist

‘Tokyo is already densely developed and designed, so it is hard to design park areas. One example is Roppongi Hills, where the developers included a park with green space and water for people’s comfort.’ – Academic

However, green spaces are not always ‘usable’. While cherry blossom (hanami) season encourages picnics in the park, a good opportunity to socialise, relax, and meet people beyond one’s colleagues and family, at other times of the year this use of green space is often considered inappropriate.

‘Parks have too many fixed benches, too many plants, and not enough open space. They have early closing times and signs to stay off the grass. And I think guards panic when they see people using a green space that is not designated for that purpose.’ – Urban designer

‘Some of the existing green places in Tokyo are the grounds of temples and shrines, but we cannot use these spaces for games or picnics, for example’ – Architect

In the Edo period, Tokyo had many rivers and aqueducts, but many now flow beneath the city; some of these are now visible in the form of green walking and cycling routes above ground. These take the form of green median strips in roadways (eg the River Green Road 九品仏川緑道 in Jiyugaoka) or run parallel to roadways; there are also green pedestrian pathways and narrow pathways that run alongside houses. Some of these paths do still retain a reduced form of running water, which is occasionally landscaped into long, narrow parks.

Tokyo still has overground rivers and canals, but since WWII, their waterfronts have been lined by warehouses and other industrial facilities, the water polluted, and the areas avoided by residents. However, more recently Tokyo has improved water quality. For example, the Sumida River has seen stronger plant wastewater regulations, dredging, purification water from Tone and Arakawa Rivers, and sewage system development. This has enabled exploration of the opportunities of waterside development (Tokyo Construction Bureau). A number of pleasure boats now ply the river, and an occasional kayak is seen. The Sumida River Terrace now features a riverside trail with plants. It is intended for walking and relaxing, yet it is usually only busy for seasonal festivals, and learning from riverside developments in other cities, and has further opportunities for development.

The Development Policy for City Planning Park and Green Space (2011) seeks to ‘revive beautiful city Tokyo surrounded by water and green corridors’ and explicitly recognises urban greenery ‘as a place of relief for Tokyo citizens’. This recognition of the benefits of nature is reiterated in the Metropolitan Area Readjustment Act (1958, frequent revisions), spawning various Green Action Plans, which prioritise the need to ‘conserve green spaces that embrace the healthy natural environment’. There is an added incentive in Tokyo to invest in open green spaces as evacuation locations in the event of natural disasters. A range of laws, including the Urban Park Act, the Landscapes Act and the Urban Green Space Conservation Act, supports these efforts. The current Tokyo City Planning Vision (Episode 4, P 117-123) by the Bureau of Urban Development envisions green roofs, ground level planting, additional lawns and riverside greenery, and using plants to create more shadow in order to reduce heat.

Referring to nature is not always helpful in urban design discussions: nature can be perceived as a threatening concept in Japan, so it may be more helpful to refer to ‘green space’.

‘European nature seems to be calm and well-controlled by humans. But [in Japan] we are in awe of nature, sometimes nature bears down on us as natural disaster, like typhoons, earthquakes, tsunamis.’ - Academic

Specific actions to improve access to nature in Tokyo

Designating green zones:

Tokyo’s Comprehensive Policy for Preserving Greenery (2010) has led to designation of special districts and zones in Tokyo, including those focused on promoting greenery:

Incentivising park development by private companies:

To enhance the value of open spaces that are created in the process of large-scale urban development, the TMG established the Guideline for Greenery Development in Privately-Owned Public Spaces to facilitate the creation of spaces such as greenery networks and pro-social open spaces that create ‘the building of lively communities’.

In central Tokyo, open space is expensive. The Comprehensive Policy for Green Conservation seeks to systematically encourage retention of green space and development of new green space, including by private developers. TMG created a park usage development scheme whereby private business projects that include a certain size of park (suitable for evacuation), which they develop, manage, and make free for public access, are given preferential treatment and easing of building regulations. The first private park opened in 2009. While pseudo-public space has its problems, this approach is delivering results in Tokyo. Privately-run parks are now creating an increase in green space across the city, and improved management of city-owned parks. TMG also leverages its own resources to promote greening, for example when TMG leases land to a private company (for example as a parking lot), the leasing contract includes greening requirements, and public-private partnerships are emerging such as the riverside Sumida River Terrace project near Kiyosubashi Bridge.

‘Compared with other Asian countries whose population density is quite high, Tokyo is a less stressful city. I don’t think this is realized by a particular architect but by well-organized city planning. This city planning is unique to Japan.’ – Urban planner

Tokyo’s urban policies with the potential to impact mental health

‘Health is always the most important topic in urban planning. When we had the Meiji Restoration, a priority topic was health. We needed more sunshine to improve people’s health, which can be realized by making more windows. Once we regulated it, we could get enough windows.’ – Urban Planner

At a national level, Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism has set five goals, which may be relevant to urban design for mental health:

- Changing social environment to develop people’s self awareness on health;

- Promoting elderly people’s community participation to help them find the purpose of life;

- Preparing urban functions within walking distance from elderly people’s homes so that they can live by themselves;

- Making a city where people can safely walk, e.g. barrier-free sidewalks; and

- Improving public transportation services.

In a city governed by complex laws and policies, Tokyo, prioritisation of health in general has been important (though explicit focus on the mental aspect of health has been more limited). Japan’s National Spatial Planning Act, Capital Regional Plan (2009) expects the Tokyo area to fulfill various roles in the 21st century including: being a beautiful area where 42 million people can live comfortably; conservation and creation of a good environment; and disaster-proofing to provide safety. While Tokyo Metropolitan Government manages certain Tokyo-wide policies, which will be discussed in this paper, in general, urban policies vary substantially within the wider Tokyo prefecture, and there is scope for individual case studies of cities within Tokyo metropolis.

Tokyo has six stated goals for urban planning. Relevant for mental health, these include: restoration of green and blue spaces; and creating a city where people can live comfortably, safely, and with peace of mind. Resident consultation and active participation in the planning process is important to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, and the trend, particularly in the past decade, has been decentralisation of city planning.

Despite the proliferation of urban policies that recognise health, many of the architects, urban planners and developers interviewed reported that they were not familiar with specific laws, policies or guidelines that they were obliged or encouraged to follow that explicitly included health promotion for the population, though an exception is for older people.

‘The government does not issue policies about health for urban planners or architects, except for particular cases, such as the size of rooms in group homes for people with dementia, or the percentage of green space for developments. Architects are trained to build good environments; there is no effort to regulate them once they have qualified.’ – Developer

‘Most of the guidelines that specifically mention health are aiming for making comfortable environment for elderly people. For example, in Sugamo, which is called “Harajuku for the elderly people,” the government spent money to make the area walkable and barrier-free.’ – Urban designer

Opinions about the environmental determinants of mental health

Interviewees identified factors within the built environment that they personally considered to be associated with mental health in Japan: beauty, nature, opportunities for creativity, social connections, opportunities to contribute to the community, access to healthcare, safety, and confidence that the city is well-managed, including efficient, reliable transportation.

Access to nature: green and blue places

One of the main ways in which Tokyo’s urban design seeks to promote better mental health is by increasing citizens’ access to green space. In the Edo period, Tokyo was filled with green spaces and waterfront parks. However, with industrialisation, much of this was lost. Tokyo policies explicitly recognise the health benefits of green space:

‘Greenery in urban areas brings pleasant and comfortable features to the lifestyles of residents’ and ‘greenery brings comfort to the human spirit’. (Basic Policies for the 10-year Project for Green Tokyo, TMG 2007).

The concept of access to green space as a factor that promotes good mental health is generally recognised, particularly in the context of appreciating nature and beauty:

‘We try to make more natural things in public space by planting trees’ – Urban Planner

‘Plants are a way to improve happiness’ – Think Tank academic

‘Japanese people have this ability to screen out any ugliness and chaos, just ignore it and focus on what is beautiful’ – Health company employee

‘Japanese people care about beauty and appreciate nature and how it can be seen in the changing seasons'– Think Tank academic

In addition to having several public parks, Tokyo has a range of large, landscaped parks that can be visited for a small fee. However, the opportunities and challenges of integrating further greenery into the Tokyo cityscape, while considered congruous, may be challenging in practice, given the existing development of the city.

‘Part of Japan’s culture is having small pieces of nature around you: plants and water. This is part of the concept behind bonsai trees: the ability to feel like you are in a forest when you are in a tiny apartment’ – Policy specialist

‘Tokyo is already densely developed and designed, so it is hard to design park areas. One example is Roppongi Hills, where the developers included a park with green space and water for people’s comfort.’ – Academic

However, green spaces are not always ‘usable’. While cherry blossom (hanami) season encourages picnics in the park, a good opportunity to socialise, relax, and meet people beyond one’s colleagues and family, at other times of the year this use of green space is often considered inappropriate.

‘Parks have too many fixed benches, too many plants, and not enough open space. They have early closing times and signs to stay off the grass. And I think guards panic when they see people using a green space that is not designated for that purpose.’ – Urban designer

‘Some of the existing green places in Tokyo are the grounds of temples and shrines, but we cannot use these spaces for games or picnics, for example’ – Architect

In the Edo period, Tokyo had many rivers and aqueducts, but many now flow beneath the city; some of these are now visible in the form of green walking and cycling routes above ground. These take the form of green median strips in roadways (eg the River Green Road 九品仏川緑道 in Jiyugaoka) or run parallel to roadways; there are also green pedestrian pathways and narrow pathways that run alongside houses. Some of these paths do still retain a reduced form of running water, which is occasionally landscaped into long, narrow parks.

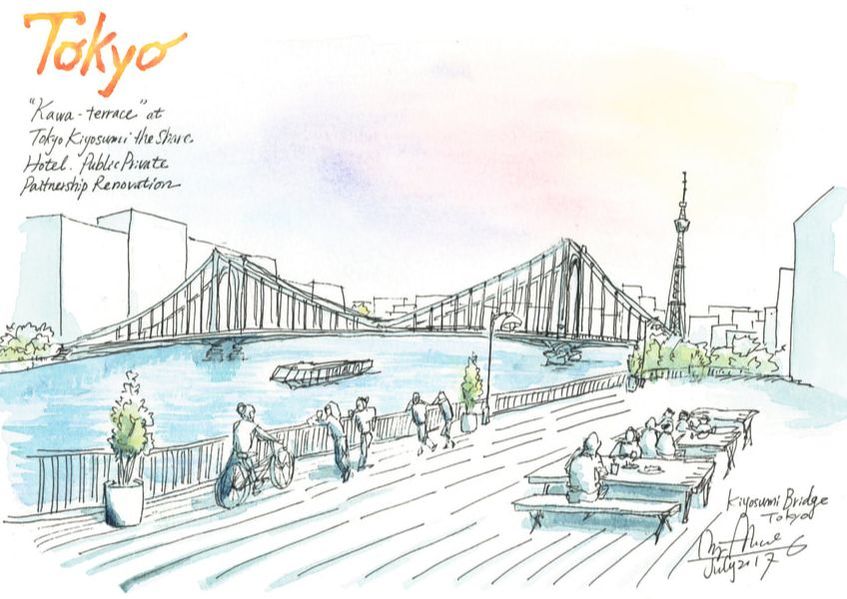

Tokyo still has overground rivers and canals, but since WWII, their waterfronts have been lined by warehouses and other industrial facilities, the water polluted, and the areas avoided by residents. However, more recently Tokyo has improved water quality. For example, the Sumida River has seen stronger plant wastewater regulations, dredging, purification water from Tone and Arakawa Rivers, and sewage system development. This has enabled exploration of the opportunities of waterside development (Tokyo Construction Bureau). A number of pleasure boats now ply the river, and an occasional kayak is seen. The Sumida River Terrace now features a riverside trail with plants. It is intended for walking and relaxing, yet it is usually only busy for seasonal festivals, and learning from riverside developments in other cities, and has further opportunities for development.

The Development Policy for City Planning Park and Green Space (2011) seeks to ‘revive beautiful city Tokyo surrounded by water and green corridors’ and explicitly recognises urban greenery ‘as a place of relief for Tokyo citizens’. This recognition of the benefits of nature is reiterated in the Metropolitan Area Readjustment Act (1958, frequent revisions), spawning various Green Action Plans, which prioritise the need to ‘conserve green spaces that embrace the healthy natural environment’. There is an added incentive in Tokyo to invest in open green spaces as evacuation locations in the event of natural disasters. A range of laws, including the Urban Park Act, the Landscapes Act and the Urban Green Space Conservation Act, supports these efforts. The current Tokyo City Planning Vision (Episode 4, P 117-123) by the Bureau of Urban Development envisions green roofs, ground level planting, additional lawns and riverside greenery, and using plants to create more shadow in order to reduce heat.

Referring to nature is not always helpful in urban design discussions: nature can be perceived as a threatening concept in Japan, so it may be more helpful to refer to ‘green space’.

‘European nature seems to be calm and well-controlled by humans. But [in Japan] we are in awe of nature, sometimes nature bears down on us as natural disaster, like typhoons, earthquakes, tsunamis.’ - Academic

Specific actions to improve access to nature in Tokyo

Designating green zones:

Tokyo’s Comprehensive Policy for Preserving Greenery (2010) has led to designation of special districts and zones in Tokyo, including those focused on promoting greenery:

- Special green space conservation districts: These districts, designated under the Urban Green Space Conservation Act, aim to ensure ‘favourable urban environments’ by conserving and promoting urban green spaces.

- Suburban green space conservation zones: These large-scale zones were designated under the Act for the Conservation of Suburban Green Zones in the National Capital Region to prevent unregulated urbanization, and explicitly aim to maintain and improve healthy minds and bodies of urban and suburban residents.

- Scenic districts: These districts aim to conserve urban scenic beauty and environment, and are subject to building restrictions under the Tokyo Scenic Area Ordinance.

Incentivising park development by private companies:

To enhance the value of open spaces that are created in the process of large-scale urban development, the TMG established the Guideline for Greenery Development in Privately-Owned Public Spaces to facilitate the creation of spaces such as greenery networks and pro-social open spaces that create ‘the building of lively communities’.

In central Tokyo, open space is expensive. The Comprehensive Policy for Green Conservation seeks to systematically encourage retention of green space and development of new green space, including by private developers. TMG created a park usage development scheme whereby private business projects that include a certain size of park (suitable for evacuation), which they develop, manage, and make free for public access, are given preferential treatment and easing of building regulations. The first private park opened in 2009. While pseudo-public space has its problems, this approach is delivering results in Tokyo. Privately-run parks are now creating an increase in green space across the city, and improved management of city-owned parks. TMG also leverages its own resources to promote greening, for example when TMG leases land to a private company (for example as a parking lot), the leasing contract includes greening requirements, and public-private partnerships are emerging such as the riverside Sumida River Terrace project near Kiyosubashi Bridge.

Sumida River Terrace project is a public-private partnership that seeks to deliver a waterside venue for walking, cycling, and socialising in Tokyo.

Artist: Ryoji Noritake

Artist: Ryoji Noritake

Machizukuri (Empowering citizens for community design):

“Machizukuri (街づくり) became popular to stimulate energy of cities by developing good residential environment.’ – Architect

A key way in which machizukuri is exhibited is through empowering citizens to deliver a green city. Tokyo is remarkable for having relatively few parks, yet a profusion of greenery. Much of this lives in plant pots and tree bases that line the streets outside people’s homes.

“Everyone engages in design of public space, but the Japanese style of placemaking is to make things beautiful.’ – Architect

TMG has stated that ‘the leading players in restoring greenery to Tokyo are its citizens’. They elaborate that to restore greenery of Tokyo ‘it is necessary for each citizen of Tokyo to take an interest in greenery. The driving force for creating a verdant Tokyo will be people’s wish to nurture green areas in their lives in which greenery is scare and to cherish abundant greenery’. To this end, the TMG has encouraged ‘greenery tended carefully by residents’, including encouraging planting of trees (including a practice of ‘memorial trees’ to celebrate special events like graduation or marriage), and turfing of school playgrounds. TMG recommends approaches to help residents green their neighbourhoods and to empower them, delivers workshops and shares methodology to green rooftops, wall surfaces, railroad areas and parking lots. TMG encourages fundraising to develop new parks, and offers tax incentives to encourage residents’ efforts, and also provides tax incentives on contributions to a ‘green fund’.

TMG seeks to ‘match’ community needs with local business to achieve green aspirations. There is a range of initiatives that enable local citizens to work with professional urban designers. The TMG registers groups that engage proactively in activities to ‘enhance community charm’ by ‘incorporating local colour and characteristics’. And the Ordinance on the Promotion of Stylish Townscape Creation in Tokyo (2003) led to a program that empowers Tokyo citizens, via Townscape Preparatory Committees, to work with the private sector to develop attractive townscapes. This has resulted in Tokyo citizens planting and maintaining greenery in tiny public spaces next to their property all over the city, ostensibly greening the city at the individual level.

Investing in Kankyojiku (Environmental Green Axes):

Kankyojiku are networks of urban spaces around roads, rivers, parks, and infrastructure that are ‘lush with greenery’ and create a network of ‘environmental green axes throughout the city. The principle of kankyojiku spaces is that whenever urban facilities are being developed, deep, wide greenery is integrated to deliver ‘pleasant landscapes’ and ‘scenic beauty’ for local communities. The TMG published Kankyojiku guidelines in 2007 with the aim of forming more kankyojiku; the Kankyojiku Council was established the following year to promote development of these areas, and to share lessons from places where Kankyojiku has already been implemented.

Access to Shinrin yoku (forest bathing)

Japan has long enjoyed a health tradition of onsen bathing (hot mineral waters). Shinrin yoku, is a term developed by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries in 1982 to describe a therapeutic health practice that aims to boost immunity, reduce stress, and promote wellbeing. Shinrin yoku is often called ‘forest bathing’ but more literally means ‘taking in the forest atmosphere’ – the opportunity for city dwellers to spend leisurely time in the forest without any distractions. Japanese research has found associations between this nature immersion and improvements in physiological and psychological indicators of stress, mood hostility, fatigue, confusion and vitality (Park et al, 2010). In particular, the research suggests that forests located at high elevations with low atmospheric pressure can help reduce depression. Throughout Japan, there are 48 official forest routes for Shinrin yoku, designated where research has demonstrated health benefits. There are five official shinrin yoku trails within Tokyo metropolis, found at Okutama forest, on the western edge of Tokyo, and accessible by affordable train. At weekends, extra direct trains from Tokyo city centre are available. There are also some limited opportunities for immersion in forest surroundings even in the very centre of Tokyo. Around a quarter of the Tokyo population are said to participate in shinrin yoku, and some companies even include visits as part of their company health plan.

Designing Active Spaces

Tokyo is a city of commuters, but not of car ownership. The metropolis is huge, the housing prices in central areas are expensive, the suburbs are large and sprawling, the public transit system is crowded yet affordable, efficient and effective, and as such, many people spent substantial time commuting each day by public transportation (the average one-way commute to work is around 45 minutes). Car ownership is low in Tokyo (0.46 cars per household, compared to the Japan average of 1.07 and the US average of 1.95) (Hongo, 2014).

Tokyo’s citizens naturally integrate light exercise into their daily routines to a greater extent than other cities through active transport (walking, cycling, and public transit).

Walking: The Bureau of Social Welfare and Public Health at Tokyo Metropolitan Government seek to increase walking under the tagline ‘small efforts, lasting health’, with an explicit note that walking improves mental health: ‘walking can be a great change of mood and stress-release’. This effort includes a website publishing Tokyo walking maps, searchable by distance and time, and by accessibility from various train lines, and encourages walking in "urban oases": ‘The sound of chirping birds and running water, the sight of beautiful foliage, the fragrance of seasonal flowers, and more—nature has a way of truly refreshing the body and mind’ and participation in pro-social walking events. The city also provides some outdoor exercise equipment, though this is not always easy to find. The Guideline to Promote Town Planning of Health, Medical Care and Welfare - Technical Advice from Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism considers a pedestrian-friendly environment as a component of healthy ageing, and walkability is explicitly part of living space planning for older people. This Guideline notes the importance of views along the pedestrian pathway, resting places, and high quality of pathway maintenance for safety, and emphasizes that people are more willing to walk and exercise if the surrounding environment is planned with social space and facilities, such as resting spots and parks. And the Japan Health Promotion Fitness Foundation is increasing its recommendation of 8000 steps/day.

‘From a viewpoint of urban planning, we don’t have many parks and green spaces. But still, we can keep long life expectancy by walking. People have to walk even after they become old. For example, people have to use train and stairways. In contrast, once people start living in the US, people use cars.’ – Urban planner

‘Increasing walking and pedestrianisation is primarily to ease congestion, improve safety, reduce pollution, and benefit physical health – but of course there is a mental health benefit’ – Think Tank academic

Public transport: Tokyo has the highest usage of public transit in the world. Reasons for the success of Tokyo’s public transit system include its reach, efficiency, reliability, affordability, and dependability. This facilitates access to the full breadth of the city, regardless of where in the outer suburbs people may live.

‘At any station in Tokyo, we have so many passengers on the station platform. However, Japanese people don’t feel stress because trains are punctual and come one after another. People know they can get another train soon. In this sense, stress can be reduced by good railway management.’ – Urban planner

However, there are persistent challenges with overcrowding, and in addition to discomfort and stress, there are some safety challenges associated with being in such close proximity to each other, particularly for women who may experience sexual harassment including unwanted sexual contact from chikan (gropers) or voyeuristic "up-skirt" photography; the latter trend has led to two main design changes in the last two decades:

Long working hours, safety, and some of the shortest sleeping times in the world mean that many people commuting to Tokyo spend their commuting time having a restorative nap – though this type of sleep can be easily disrupted and of a poorer quality than sleep at home; furthermore very crowded train carriages preclude sleep, and many other opportunities for relaxation in transit

‘You can design the city to shorten commuting time. People in Tokyo sleep, on average, 5 hours and half at home, and they add to that their sleep during the commuting time in a train.’ – Architect

Train stations are accessible and often barrier-free, which means that regardless of physical ability, people tend to walk from stations to their destinations rather than use cars, leading to natural integration of physical activity into people’s daily routines. This has also led to channelling of much car traffic onto larger roads, while smaller networks of roads have few cars (and those that access these roads do so at low speed that prioritises pedestrians). Often these roads do not have pavements (sidewalks) due to such low car traffic, informally creating an pedestrian and bike-friendly thoroughfare reminiscent of Barcelona’s ‘superblocks’.

However, the general population’s appreciation of the natural exercise opportunities afforded by active transport may be more limited; exercise is often viewed as a hobby and people are more likely to consciously incorporate physical activity into their life as part of an organised exercise group, choosing designated exercise areas with formal facilities, such as the few running routes with adjacent showers and lockers, or well-managed playing fields in suburban parts of the city. Affordable, accessible and efficient public transport ensures accessibility to such areas.

‘People do use public transport, but you’ll see them standing in line for the escalator rather than using the stairs. They don’t commute like this for the exercise benefits’ – Health company employee

‘Sports are popular only really within clubs, as an extension of school clubs. Fewer people exercise alone. But where they do exercise, there is usually good infrastructure, such as showers near the Imperial moat jogging route.’ – Health company employee

'You see playing fields all along the river, and at the weekend they are full of people playing baseball or soccer. The playing fields are all booked for a specific period, it’s all managed meticulously, and everybody has their role, like cleaning the pitch.' – Heath company employee

Cycling: Bicycles are another key form of transportation in Tokyo, but they are used in different ways than in many other cities. Around 14% of journeys in Tokyo each day are made by bike; however, these were largely shorter journeys (under 2km), and are often undertaken by women in the course of a domestic routine that may involve such tasks as shopping, getting to the train station, and picking children up from school. These women ride bikes referred to informally as the ‘mamachari’, and these affordable, light ‘mother’s bikes’ have become a cultural icon, affording women independence, physical activity, access to social and natural settings, and other benefits of cycling. They emerged in the 1950s and with their space for baskets, luggage racks and multiple child seats have made cycling accessible and convenient for women and their families. The government sought to impose a limit of one child to be carried per mamachari, provided the cyclist is over 16, a child seat is attached, and the child is under the age of six. Mothers complained, and the number of child passengers permissible was increased to a limit of two (though in reality, three children riders per mamachari are often observed). Mamacharis often share pavements (sidewalks) with pedestrians, or use smaller roads.

“Riding a mamachari is safe because everyone rode one as a child, and of course our mother rode one, and now our children ride them, and our wife rides them, so of course we are careful when driving near a mamachari.” - Architect

It is thought that up to 9% of employees across Japan cycle to work. Bicycles are used less often by workers on their commutes compared to other large cities largely due to bureaucratic barriers. Corporate law requires companies across Japan to insure their staff for accidents, which includes commuting, and insurance policies often fail to cover cycling. There can also be disputes on what specific part of the journey is regarded as commuting (for instance when cyclists stop somewhere en route). Companies may also be liable for payment of costs for commuting by bicycle (such as bicycle repairs). As a result, companies generally impose bans on cycling to work (though some operate a ‘don’t ask don’t tell policy’, and occasional others promote cycling for environmental and health benefits).

'In the building next to us, staff members are forbidden from cycling to work, because of the risk of accidents and insurance claims. It’s a shame as there is great bike parking around here. Some of the staff do it sneakily anyway.'– Health company employee

An important impact of these restrictions has been that formal bicycle infrastructure is limited in Japan:

Urban design for physical activity in Tokyo's plans and the upcoming Olympic Games legacy

Tokyo will host the Summer Olympic Games in 2020. The building, policymaking and legacy-building requirements International Olympic Committee may create a further catalyst, in particular, inspiring Tokyo to adopt successes from other cities:

‘By 2020, Tokyo has to compete with other cities such as New York and Beijing, for example, it will have to build more bicycle lanes on the road. External pressure urges Japan to take more designs from other cities and improve. If London built 100 km of bike lanes, Tokyo will want to build 110 km. That’s how it works.’ – Architect

While physical health legacy has not yet been very explicit in Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Olympic ambitions, a series of policies and plans are emerging that contain physical activity promotion and facilitation aspirations. A three-year (2015-2017) progress plan has been set as part of The Long-Term Vision for Tokyo and Citizen First – Building a New Tokyo – Action Plan to 2020 (P.259-261).

Pro-Social Space

Public spaces are often the epicentre of positive, natural social interaction in a city, and this is widely recognised as an important factor in maintaining good mental health and building resilience. Tokyo tends not to have town squares, which form natural public open spaces in many Western countries. Tokyo values public spaces as settings for people to socialise, but this is not always reflected in pro-social design; the priority for open space design is more likely to be evacuation space in case of earthquakes.

‘We need gathering spaces’ – Public Health Specialist

‘If people feel that they are a part of the society and community through social activities in open public spaces, it is good for their mental health.’ – Architect

‘Buildings made of wood with fewer edges and squares creates permeable architecture that encourages public social life.’ – Urban designer

‘Good social connections among the neighborhood will help prepare for a big disaster.’ – Architect

Outdoor public places

‘There are three types of public places in Tokyo: public parks, train plazas and temples/shrines.’ – Urban planner

Public parks:

‘If you go to pachinko (a pinball gambling game) or shopping centre, you will notice the lack of diversity. However, parks are open for anyone. You can see all the generations, including rich, poor, elderly and young people.’ – Architect

‘If parks are used for community activities, it can lead to improved mental health.’ – Urban designer

Train station plazas

‘Evacuation space for earthquakes takes priority over placemaking. Station plazas are mostly empty other than smoking areas. There is opportunity for development, such as removing smoking areas, and having benches – benches with a more social layout to encourage social interaction.’ – Academic

Temples and shrines

‘Public life once happened at the shrines and temples – these were our version of town squares. Now public life happens in streets and alleys.’ – Architect

'Temples and shrines have many community events – matsuri (festivals), markets...’ – Urban planner

‘They have open space, but many people think temples and shrines are for praying, not sitting. Maybe there is opportunity to develop benches just outside the temple gates.’ – Urban planner

Indoor public places

Value is increasingly being recognised in the potential of indoor public spaces to reap the benefits of pro-social interaction in Tokyo. In particular, there is discussion in Tokyo of how to better harness shopping centre design and facilities to improve health and wellbeing, envisioning the centre of a shopping mall as a new version of a city’s town square, how to design bars to facilitate positive social discussions, and how to better design urban workplaces to help counteract the potentially negative health effects of Tokyo’s trend for very long working hours.

Shopping places

‘Shopping areas next to train stations belong to the train company and generate income – but they are often ‘placeless spaces’, that do not reflect the neighbourhood at all.’ - Academic

‘Shotengai (indoor/covered shopping arcades) feel very connected with their local communities… shopping malls can be more placeless’. – Academic

‘Shopping malls have evolved to have more open spaces and high ceilings to reduce stress and let people sit, relax and talk. Sometimes there are classes or markets or other activities’ – Policy Specialist

‘Temples and shrines often have an associated retail corridor. This integrates them with the community and tourism.’ – Urban planner

Bars

‘In Akabane, there is a famous drinking place with a ko-shaped counter. The “Ko” shape (‘ko’ is the pronunciation of the Japanese katakana symbol コ) was invented to increase people’s happiness, to share their smiles with other visitors while they drink.’ – Urban designer

Offices

‘Designers are trying to address the stress caused by long working hours – they do that by increasing social interaction, through more open spaces in the office, and by making routes more inconvenient, so that people moving around the office or university have more movement and more social interactions’ – Policy Specialist.

Places for older people

The opportunities of older people to move around their neighbourhoods and socialise is valued, and a new aspect of Tokyo’s long term care policies seeks to bring urban planning into play, with ‘designated activity areas’, often around a station, that bring together shops and services, home care, health facilities and social facilities in convenient, barrier-free ‘daily activity areas’. There have also been experiments with ‘healthy roads’ in Tokyo, widening the road to facilitate pedestrian traffic of different speeds, again clustering these range of services in an accessible way.

Post-disaster places

Finally, experiences of disasters in Tokyo and the surrounding regions have led to post-traumatic stress and contributed to the city’s focus on opportunities to support people’s mental health through architecture and planning, and facilitating pro-social opportunity has emerged as a key factor.

‘People were traumatised after 3/11 (tsunami and earthquake), so we had to think about city design. People evacuated due to the tsunami were living in temporary housing, which was stressful for most people. We made shared space at the entrance of their temporary housing to increase social interaction and community spaces with gardens.’ – Architect

‘Entrances were designed to face each other rather than side by side to promote sociability.’ – Architect

Safe Space

Tokyo prioritises the safety of its citizens in two main ways: it wants to be the safest city in the world in terms of crime, and it must safeguard its population in case of natural disasters. Tokyo’s crime rates are low, and with an ever-present risk of disasters such as earthquakes, crime did not factor into discussions of urban design opportunity: much of the focus on safety in Tokyo was in the context of disaster preparedness. However, the ever-present risk of earthquakes was not felt to be a concerning factor, as people feel the city prepares them adequately for the risk with clear information and training opportunities. Design interventions to enhance safety in Tokyo include earthquake-resistant buildings and firebreak belts, along with barrier-free design, to enable the safe movement of older people and those with disabilities around the city.

‘Earthquakes are the biggest safety threat in Tokyo.’ – Health company employee

‘People feel little stress because Tokyo is safe and clean. If there is an earthquake, we all know what to do, we are all ready, so we do not have to fear; nuclear risks are a big fear.’ – Urban planner

Another way in which Tokyo promotes safety is in the city’s barrier-free aspirations, including residential housing, public amenities and transportation. This plan focuses on improving the quality of life and urban participation of older people and those with disabilities. (Tokyo City Planning Vision Episode 4, P.140, by Bureau of Urban Development)

Perceived prioritisation of mental health in urban planning and design in Tokyo

There was a consensus amongst those interviewed that mental health is not currently considered to be a priority within urban policymaking, architecture or urban planning.

‘I think some cities are definitely interested in physical health intervention in city planning, though people’s interest in mental health is still limited.’ – Architect.

Partly, the lack of explicit focus on mental health may be attributed to conceptualisation of the term ‘mental health’, which was not familiar to people; 'mental health' was considered synonymous with mental illness, and interviewees used words such as ‘stress’, ‘peace’ and ‘comfort' to describe the concept.

‘People think about peaceful comfort, and about reducing the stress caused by long hours at the office, but not specifically about mental health.’ – Academic

‘Some neighbourhood developments focus on comfort, but do not have a specific health focus’. – Developer

The first explicit policy linking urban living and health by Tokyo Metropolitan Government seems to have been in 1972. However it was not until the 1990s that the city started to measure people’s ‘life evaluation’. More recently, there has been a trend of promoting the concept of urban ‘happiness’, particularly in the context of delivering sustainable cities, in line with global declarations such as the Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Development Goals:

‘Since the 1980s, ‘smile’ and ‘happiness’ have been included in the name of declarations.’ – Architect

‘Happiness is being recognised as a tool to drive sustainability.’ – Academic

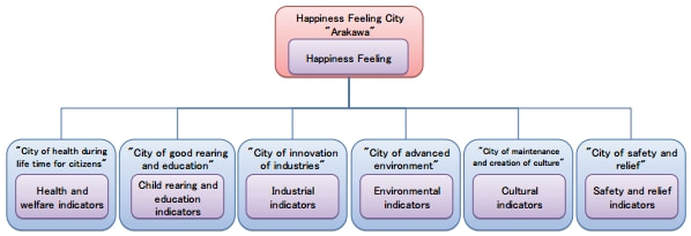

In 2011, a prefectural ranking of wellbeing was published, leading to a flurry of measurements of wellbeing across the country (for example, in Shiga prefecture in 2012, residents proposed a ‘smile index of wellbeing’; the Tosa Association of Corporate Executives released the Gross Kochi Happiness (GKH) index; 52 local governments across the country launched a ‘Happiness League’; and in 2015, Arakawa City in Tokyo published its first "Gross Arakawa Happiness (GHA) Report" inspired by Bhutan’s measurement of happiness (Figure 1).

“Machizukuri (街づくり) became popular to stimulate energy of cities by developing good residential environment.’ – Architect

A key way in which machizukuri is exhibited is through empowering citizens to deliver a green city. Tokyo is remarkable for having relatively few parks, yet a profusion of greenery. Much of this lives in plant pots and tree bases that line the streets outside people’s homes.

“Everyone engages in design of public space, but the Japanese style of placemaking is to make things beautiful.’ – Architect

TMG has stated that ‘the leading players in restoring greenery to Tokyo are its citizens’. They elaborate that to restore greenery of Tokyo ‘it is necessary for each citizen of Tokyo to take an interest in greenery. The driving force for creating a verdant Tokyo will be people’s wish to nurture green areas in their lives in which greenery is scare and to cherish abundant greenery’. To this end, the TMG has encouraged ‘greenery tended carefully by residents’, including encouraging planting of trees (including a practice of ‘memorial trees’ to celebrate special events like graduation or marriage), and turfing of school playgrounds. TMG recommends approaches to help residents green their neighbourhoods and to empower them, delivers workshops and shares methodology to green rooftops, wall surfaces, railroad areas and parking lots. TMG encourages fundraising to develop new parks, and offers tax incentives to encourage residents’ efforts, and also provides tax incentives on contributions to a ‘green fund’.

TMG seeks to ‘match’ community needs with local business to achieve green aspirations. There is a range of initiatives that enable local citizens to work with professional urban designers. The TMG registers groups that engage proactively in activities to ‘enhance community charm’ by ‘incorporating local colour and characteristics’. And the Ordinance on the Promotion of Stylish Townscape Creation in Tokyo (2003) led to a program that empowers Tokyo citizens, via Townscape Preparatory Committees, to work with the private sector to develop attractive townscapes. This has resulted in Tokyo citizens planting and maintaining greenery in tiny public spaces next to their property all over the city, ostensibly greening the city at the individual level.

Investing in Kankyojiku (Environmental Green Axes):

Kankyojiku are networks of urban spaces around roads, rivers, parks, and infrastructure that are ‘lush with greenery’ and create a network of ‘environmental green axes throughout the city. The principle of kankyojiku spaces is that whenever urban facilities are being developed, deep, wide greenery is integrated to deliver ‘pleasant landscapes’ and ‘scenic beauty’ for local communities. The TMG published Kankyojiku guidelines in 2007 with the aim of forming more kankyojiku; the Kankyojiku Council was established the following year to promote development of these areas, and to share lessons from places where Kankyojiku has already been implemented.

Access to Shinrin yoku (forest bathing)

Japan has long enjoyed a health tradition of onsen bathing (hot mineral waters). Shinrin yoku, is a term developed by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries in 1982 to describe a therapeutic health practice that aims to boost immunity, reduce stress, and promote wellbeing. Shinrin yoku is often called ‘forest bathing’ but more literally means ‘taking in the forest atmosphere’ – the opportunity for city dwellers to spend leisurely time in the forest without any distractions. Japanese research has found associations between this nature immersion and improvements in physiological and psychological indicators of stress, mood hostility, fatigue, confusion and vitality (Park et al, 2010). In particular, the research suggests that forests located at high elevations with low atmospheric pressure can help reduce depression. Throughout Japan, there are 48 official forest routes for Shinrin yoku, designated where research has demonstrated health benefits. There are five official shinrin yoku trails within Tokyo metropolis, found at Okutama forest, on the western edge of Tokyo, and accessible by affordable train. At weekends, extra direct trains from Tokyo city centre are available. There are also some limited opportunities for immersion in forest surroundings even in the very centre of Tokyo. Around a quarter of the Tokyo population are said to participate in shinrin yoku, and some companies even include visits as part of their company health plan.

Designing Active Spaces

Tokyo is a city of commuters, but not of car ownership. The metropolis is huge, the housing prices in central areas are expensive, the suburbs are large and sprawling, the public transit system is crowded yet affordable, efficient and effective, and as such, many people spent substantial time commuting each day by public transportation (the average one-way commute to work is around 45 minutes). Car ownership is low in Tokyo (0.46 cars per household, compared to the Japan average of 1.07 and the US average of 1.95) (Hongo, 2014).

Tokyo’s citizens naturally integrate light exercise into their daily routines to a greater extent than other cities through active transport (walking, cycling, and public transit).

Walking: The Bureau of Social Welfare and Public Health at Tokyo Metropolitan Government seek to increase walking under the tagline ‘small efforts, lasting health’, with an explicit note that walking improves mental health: ‘walking can be a great change of mood and stress-release’. This effort includes a website publishing Tokyo walking maps, searchable by distance and time, and by accessibility from various train lines, and encourages walking in "urban oases": ‘The sound of chirping birds and running water, the sight of beautiful foliage, the fragrance of seasonal flowers, and more—nature has a way of truly refreshing the body and mind’ and participation in pro-social walking events. The city also provides some outdoor exercise equipment, though this is not always easy to find. The Guideline to Promote Town Planning of Health, Medical Care and Welfare - Technical Advice from Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism considers a pedestrian-friendly environment as a component of healthy ageing, and walkability is explicitly part of living space planning for older people. This Guideline notes the importance of views along the pedestrian pathway, resting places, and high quality of pathway maintenance for safety, and emphasizes that people are more willing to walk and exercise if the surrounding environment is planned with social space and facilities, such as resting spots and parks. And the Japan Health Promotion Fitness Foundation is increasing its recommendation of 8000 steps/day.

‘From a viewpoint of urban planning, we don’t have many parks and green spaces. But still, we can keep long life expectancy by walking. People have to walk even after they become old. For example, people have to use train and stairways. In contrast, once people start living in the US, people use cars.’ – Urban planner

‘Increasing walking and pedestrianisation is primarily to ease congestion, improve safety, reduce pollution, and benefit physical health – but of course there is a mental health benefit’ – Think Tank academic

Public transport: Tokyo has the highest usage of public transit in the world. Reasons for the success of Tokyo’s public transit system include its reach, efficiency, reliability, affordability, and dependability. This facilitates access to the full breadth of the city, regardless of where in the outer suburbs people may live.

‘At any station in Tokyo, we have so many passengers on the station platform. However, Japanese people don’t feel stress because trains are punctual and come one after another. People know they can get another train soon. In this sense, stress can be reduced by good railway management.’ – Urban planner

However, there are persistent challenges with overcrowding, and in addition to discomfort and stress, there are some safety challenges associated with being in such close proximity to each other, particularly for women who may experience sexual harassment including unwanted sexual contact from chikan (gropers) or voyeuristic "up-skirt" photography; the latter trend has led to two main design changes in the last two decades:

- A designated women-only train carriage on many train lines during morning rush hours when the trains are particularly crowded. Elementary school-age boys, male passengers with disabilities, or male carers travelling with disabled passengers may also use these carriages. There is no law against other males using them, but this is discouraged and evokes social stigma.

- A compulsory shutter sound that cannot be disabled for all mobile phones with camera functions that are sold in Japan (this feature is mandated by phone companies, not by law, but all phone manufacturers and carriers comply).

Long working hours, safety, and some of the shortest sleeping times in the world mean that many people commuting to Tokyo spend their commuting time having a restorative nap – though this type of sleep can be easily disrupted and of a poorer quality than sleep at home; furthermore very crowded train carriages preclude sleep, and many other opportunities for relaxation in transit

‘You can design the city to shorten commuting time. People in Tokyo sleep, on average, 5 hours and half at home, and they add to that their sleep during the commuting time in a train.’ – Architect

Train stations are accessible and often barrier-free, which means that regardless of physical ability, people tend to walk from stations to their destinations rather than use cars, leading to natural integration of physical activity into people’s daily routines. This has also led to channelling of much car traffic onto larger roads, while smaller networks of roads have few cars (and those that access these roads do so at low speed that prioritises pedestrians). Often these roads do not have pavements (sidewalks) due to such low car traffic, informally creating an pedestrian and bike-friendly thoroughfare reminiscent of Barcelona’s ‘superblocks’.

However, the general population’s appreciation of the natural exercise opportunities afforded by active transport may be more limited; exercise is often viewed as a hobby and people are more likely to consciously incorporate physical activity into their life as part of an organised exercise group, choosing designated exercise areas with formal facilities, such as the few running routes with adjacent showers and lockers, or well-managed playing fields in suburban parts of the city. Affordable, accessible and efficient public transport ensures accessibility to such areas.

‘People do use public transport, but you’ll see them standing in line for the escalator rather than using the stairs. They don’t commute like this for the exercise benefits’ – Health company employee

‘Sports are popular only really within clubs, as an extension of school clubs. Fewer people exercise alone. But where they do exercise, there is usually good infrastructure, such as showers near the Imperial moat jogging route.’ – Health company employee

'You see playing fields all along the river, and at the weekend they are full of people playing baseball or soccer. The playing fields are all booked for a specific period, it’s all managed meticulously, and everybody has their role, like cleaning the pitch.' – Heath company employee

Cycling: Bicycles are another key form of transportation in Tokyo, but they are used in different ways than in many other cities. Around 14% of journeys in Tokyo each day are made by bike; however, these were largely shorter journeys (under 2km), and are often undertaken by women in the course of a domestic routine that may involve such tasks as shopping, getting to the train station, and picking children up from school. These women ride bikes referred to informally as the ‘mamachari’, and these affordable, light ‘mother’s bikes’ have become a cultural icon, affording women independence, physical activity, access to social and natural settings, and other benefits of cycling. They emerged in the 1950s and with their space for baskets, luggage racks and multiple child seats have made cycling accessible and convenient for women and their families. The government sought to impose a limit of one child to be carried per mamachari, provided the cyclist is over 16, a child seat is attached, and the child is under the age of six. Mothers complained, and the number of child passengers permissible was increased to a limit of two (though in reality, three children riders per mamachari are often observed). Mamacharis often share pavements (sidewalks) with pedestrians, or use smaller roads.

“Riding a mamachari is safe because everyone rode one as a child, and of course our mother rode one, and now our children ride them, and our wife rides them, so of course we are careful when driving near a mamachari.” - Architect

It is thought that up to 9% of employees across Japan cycle to work. Bicycles are used less often by workers on their commutes compared to other large cities largely due to bureaucratic barriers. Corporate law requires companies across Japan to insure their staff for accidents, which includes commuting, and insurance policies often fail to cover cycling. There can also be disputes on what specific part of the journey is regarded as commuting (for instance when cyclists stop somewhere en route). Companies may also be liable for payment of costs for commuting by bicycle (such as bicycle repairs). As a result, companies generally impose bans on cycling to work (though some operate a ‘don’t ask don’t tell policy’, and occasional others promote cycling for environmental and health benefits).

'In the building next to us, staff members are forbidden from cycling to work, because of the risk of accidents and insurance claims. It’s a shame as there is great bike parking around here. Some of the staff do it sneakily anyway.'– Health company employee

An important impact of these restrictions has been that formal bicycle infrastructure is limited in Japan:

- Protected bike lanes are rare. From observation, cyclists wearing cycling clothing and helmets tend to cycle in the roads, but commonly, cyclists in work or casual clothes will informally share pavements (sidewalks) with pedestrians. This is technically only permitted where there are specific signs indicating cyclists can use the pavements (sidewalks) or for children; a third permission is more open to interpretation: when it is found to be unavoidable, in light of roadway or traffic conditions, for said standard bicycle to travel on a sidewalk in order to ensure the safety of said standard bicycle. (Road Traffic Act 2015, Article 63-4).

- Bike parking is challenging, and often requires payment or accessing special bike park locations, with bikes removed by police when parked in informal spaces. It is unusual for workplaces to provide bike parking.