|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:7

|

RESEARCH

From sociopetal to sociofugal: a reverse procedure of Tehran urban spaces

Rethinking future developments of Shemiranat

Shahram Taghipour Dehkordi (1) and Milad HeidariSoureshjani (2)

(1) Department of Art, Faculty in Art and Architecture, Shahrekord branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord, Iran

(2) Department of Art, Lecturer in Art and Architecture, Shahrekord branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord, Iran

(1) Department of Art, Faculty in Art and Architecture, Shahrekord branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord, Iran

(2) Department of Art, Lecturer in Art and Architecture, Shahrekord branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord, Iran

Introduction

Since urban space is mostly in hands of private sector, capitalism can trigger urban space formation in contemporary cities. This trend is associated with privatization of urban spaces, and drives urban spaces to act as transient routes and connection passages (Carmona, 2010). While encouraging the so-called “mechanical life”, these forces can ignore the need for public spaces that invite social engagement, leading to declining quality of the urban environment (Gehl, 1987:60). The issue can be exacerbated when governments policies take actions such as those seen in Iranian metropolitan public spaces, including: selling historical tourist hubs to the private sector, privatizing public gardens by fencing, and imposing strict surveillance on coffee shops and gathering places other than religious centers.

The focal points of the city of Tehran in Iran are Tajrish Square (an urban space) and Shemiranat (an urban area). These are examples of areas that have been affected by privatization alongside subjection to unsuitable government policies. As a consequence, Tajrish and Shemiranat have lost their capability to bring people together and stimulate interaction as pedestrian routes merge and overlap (sociopetal spaces). As a result, less socialization and meeting/gathering occurs in the area, which increasingly tends to keep people apart and suppress communication (sociofugal spaces). This example reflects similar scenarios in other Iranian metropolitan public spaces.

These so-called sociofugal spaces (Hall,1966) underly private and fear space and are associated with massive psychological, social and economic impacts (Cornwell & J.waite: 2009, Cacioppo& Louise: 2003). This paper aims at adopting a relatively new process to identify sociofugal characteristics of the area and to propose strategies to drive the areas towards delivery of sociopetal space.

The next section of the paper sets the context for the research by examining related literature. This is followed by a description of the survey methodology, then by an analysis of the survey findings, and finally the paper’s conclusions.

Definition of urban space

The definition of urban space does not enjoy unanimous agreement among urban design theorists. Some define it using the built environment and built boundaries; others refer to it as density application; meanwhile it is mostly epitomized by streets and squares (Schultz, 1979). From a social standpoint, urban space is constituted of both social space and built space. Lefebvre concedes that these two aspects of urban spaces may not be detachable (Madanipour, 1996). Arguably, the physical environment influences its social composition, and the social environment can influence its physical composition.

In spite of various definitions, direct correlations between urban space and social aspects of life subsist. In this paper, urban space can be clarified as parts of the city, either public or private, at which people can freely interact and utilize urban facilities; this can be further classified based upon various criteria.

Gehl (1987) categorizes cities' public spaces into 4 types:

Definition of sociofugal and sociopetal urban spaces

The terms “sociofugal and sociopetal” were first used by Humphry Osmond (1966), who was the manager of Saskatchewan hospital. The terminology described hospital interior spaces with designs that dispersed patients (sociofugal) or gathered patients (sociopetal) respectively (Lang& Moleski, 2010, page 95).

Hall (1966) expanded the concept of sociofugal spaces to the city, investigating impacts of urban space barriers on people's socialization. Hall described sociofugal spaces as those characterized by the declining socialization of people, typically triggered by high-speed traffic and with isolated forms. Community severance occurs when transport infrastructure and/or the speed or volume of traffic interferes with the ability of individuals to access goods, services, and personal networks. The concept has been defined in many different ways since the 1960s, usually emphasizing the barrier effect of roads on the movement of pedestrians (Mindell et al, 2017).

The converse is sociopetal spaces, an idea presented by other theorists such as Lang (2010) where urban form can invite people to gather/ socialize in urban spaces and connect communities. Sociopetal spaces and their components could provide convenient context for optional activities. From Lang's standpoint, three factors epitomize such spaces: giving priority to pedestrians; having sensory richness; and holding human scale. He enumerated 5 qualities to achieve sociopetal spaces: a place that meets psychological needs; and safety and security needs; and provides a sense of belonging; an environment in which users can feel competent (self-esteem); and an aesthetic that fits that context.

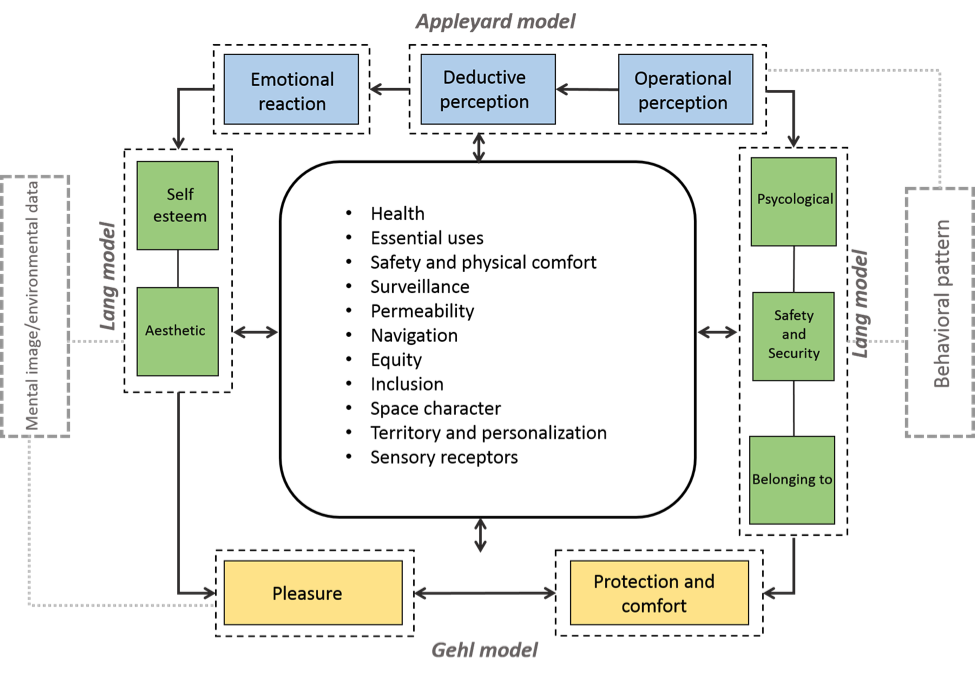

The term sociopetal has always played a significant role in urban design theorists' literature. They point to sociopetal attributes of public spaces using various keywords. Whyte (1980) in his book “Social Life of Small Urban Spaces” explored alternatives of increasing livability and people's socialization in urban spaces in his “Street Life Project”. He ultimately described street life as: a place where people talk too much and have long time farewell. Jacobs (1961) and Schultz (1979) utilize similar description with the terms “livability”, “receptive city” and “visit receptive city” respectively. The point is how designers can reach these attributes and barriers to these attitudes in urban spaces. As Appleyard (1979) states, people perception analysis is the way to support socialization attributes and make positive perceptions for people to gather and socialize in public spaces. He classifies the perception process into: operational, deductive and emotional-reaction perception (Carmona &Punter, 2010:70). Gehl (1987) defines the primary quality affecting positive perception of sociopetal spaces: pleasure, protection and comfort. Table 1 gives more indications about these attributes.

Since urban space is mostly in hands of private sector, capitalism can trigger urban space formation in contemporary cities. This trend is associated with privatization of urban spaces, and drives urban spaces to act as transient routes and connection passages (Carmona, 2010). While encouraging the so-called “mechanical life”, these forces can ignore the need for public spaces that invite social engagement, leading to declining quality of the urban environment (Gehl, 1987:60). The issue can be exacerbated when governments policies take actions such as those seen in Iranian metropolitan public spaces, including: selling historical tourist hubs to the private sector, privatizing public gardens by fencing, and imposing strict surveillance on coffee shops and gathering places other than religious centers.

The focal points of the city of Tehran in Iran are Tajrish Square (an urban space) and Shemiranat (an urban area). These are examples of areas that have been affected by privatization alongside subjection to unsuitable government policies. As a consequence, Tajrish and Shemiranat have lost their capability to bring people together and stimulate interaction as pedestrian routes merge and overlap (sociopetal spaces). As a result, less socialization and meeting/gathering occurs in the area, which increasingly tends to keep people apart and suppress communication (sociofugal spaces). This example reflects similar scenarios in other Iranian metropolitan public spaces.

These so-called sociofugal spaces (Hall,1966) underly private and fear space and are associated with massive psychological, social and economic impacts (Cornwell & J.waite: 2009, Cacioppo& Louise: 2003). This paper aims at adopting a relatively new process to identify sociofugal characteristics of the area and to propose strategies to drive the areas towards delivery of sociopetal space.

The next section of the paper sets the context for the research by examining related literature. This is followed by a description of the survey methodology, then by an analysis of the survey findings, and finally the paper’s conclusions.

Definition of urban space

The definition of urban space does not enjoy unanimous agreement among urban design theorists. Some define it using the built environment and built boundaries; others refer to it as density application; meanwhile it is mostly epitomized by streets and squares (Schultz, 1979). From a social standpoint, urban space is constituted of both social space and built space. Lefebvre concedes that these two aspects of urban spaces may not be detachable (Madanipour, 1996). Arguably, the physical environment influences its social composition, and the social environment can influence its physical composition.

In spite of various definitions, direct correlations between urban space and social aspects of life subsist. In this paper, urban space can be clarified as parts of the city, either public or private, at which people can freely interact and utilize urban facilities; this can be further classified based upon various criteria.

Gehl (1987) categorizes cities' public spaces into 4 types:

- Traditional city with its urban spaces being a context for people meeting/interaction. (Cities with peaceful coexistence of vehicles and pedestrians fit into this type). Iranian old cities with bazaars acting as the primary link contextualizing people's attendance (Pourjafar et al: 2014) are an exemplary case.

- “Invaded space” in which urban spaces are dominated with vehicle traffic. This is currently the case in most Iranian metropolitan cities.

- Absence of people in urban spaces swarming with vehicles defines the third urban space type.

- Finally, "traffic cities" such as many cities in the USA, are defined by vehicles trying to take over urban spaces.

Definition of sociofugal and sociopetal urban spaces

The terms “sociofugal and sociopetal” were first used by Humphry Osmond (1966), who was the manager of Saskatchewan hospital. The terminology described hospital interior spaces with designs that dispersed patients (sociofugal) or gathered patients (sociopetal) respectively (Lang& Moleski, 2010, page 95).

Hall (1966) expanded the concept of sociofugal spaces to the city, investigating impacts of urban space barriers on people's socialization. Hall described sociofugal spaces as those characterized by the declining socialization of people, typically triggered by high-speed traffic and with isolated forms. Community severance occurs when transport infrastructure and/or the speed or volume of traffic interferes with the ability of individuals to access goods, services, and personal networks. The concept has been defined in many different ways since the 1960s, usually emphasizing the barrier effect of roads on the movement of pedestrians (Mindell et al, 2017).

The converse is sociopetal spaces, an idea presented by other theorists such as Lang (2010) where urban form can invite people to gather/ socialize in urban spaces and connect communities. Sociopetal spaces and their components could provide convenient context for optional activities. From Lang's standpoint, three factors epitomize such spaces: giving priority to pedestrians; having sensory richness; and holding human scale. He enumerated 5 qualities to achieve sociopetal spaces: a place that meets psychological needs; and safety and security needs; and provides a sense of belonging; an environment in which users can feel competent (self-esteem); and an aesthetic that fits that context.

The term sociopetal has always played a significant role in urban design theorists' literature. They point to sociopetal attributes of public spaces using various keywords. Whyte (1980) in his book “Social Life of Small Urban Spaces” explored alternatives of increasing livability and people's socialization in urban spaces in his “Street Life Project”. He ultimately described street life as: a place where people talk too much and have long time farewell. Jacobs (1961) and Schultz (1979) utilize similar description with the terms “livability”, “receptive city” and “visit receptive city” respectively. The point is how designers can reach these attributes and barriers to these attitudes in urban spaces. As Appleyard (1979) states, people perception analysis is the way to support socialization attributes and make positive perceptions for people to gather and socialize in public spaces. He classifies the perception process into: operational, deductive and emotional-reaction perception (Carmona &Punter, 2010:70). Gehl (1987) defines the primary quality affecting positive perception of sociopetal spaces: pleasure, protection and comfort. Table 1 gives more indications about these attributes.

Table 1: Concepts analogous to 'sociopetal' by urban design theorists

Theorist |

Concept |

Definition |

Jane Jacobs (1961) |

Livability |

A place, holding diverse activities, and consequently, a variety of users |

Edward T Hall (1960) |

Sociopetal space |

A space, encouraging user to pause and gather/socialize |

William Whyte (1980) |

Street life |

A space that brings people to talk and greet each other for a long time |

Norberg Schultz (1984) |

Hosting |

A space, releasing its own components and provide context for interactions |

Jan Gehl (1987) |

Robustness |

A space, providing users to meet face to face and experiment through their sensations |

Ali Madanipour (1996) |

Social process of space |

A space, supporting socio-spatial geometry/function, mentally conforms inhabitants |

John Lang (2010) |

Receptive |

A space with human scale, having convenient context for diverse activities |

People's socialization and behavior in spaces are affected by various factors, including environment provisions, economic satisfaction, culture, society norms etc. (Pakzad & Bozorg: 2015). Based on three behavioral renowned models provided by Appleyard (1979), Lang (2010), and Gehl (1987), most of pedestrian movement/socialization activities may occur in terms of “perception-need” model. The model is an interacting cycle, gathering diverse qualities as integral for sociopetal space formation. The qualities are conclusion of various similar concepts, proposed by theorists in Table 1.

Figure 1: Proposed sociopetal framework based on perception-need models

In addition to people's movement/interaction in urban spaces, their mental engagement could also define whether a particular space is sociopetal or sociofugal, as illustrated in the model. Spatial analysis of an area could bring these two factors to light. Space syntax theory states that the more Visibility field (Isovist) for a space, the more it will be mental appealing. Spatial integration on the other hand, is strongly related to people flow and these both work together to affect social activities taking place in spaces.

The purpose of this paper is to recognize sociofugal attributes of Shemiranat urban spaces by examining spatial structure and people behavior patterns, to discuss them in terms of sociopetal framework and eventually to propose suitable strategies for the area using the AIDA method.

The case study

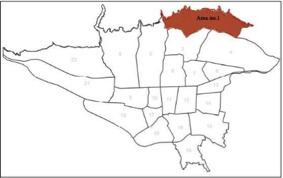

Tehran is the capital of Iran and its largest city. It has both natural and built features. There are many urban human scale spaces in the historical central part of Tehran and Shemiranat.

Shemiranat was assigned as the No.1 urban area by Tehran municipality divisions with Tajrish Sq. as the area's central and primary urban space. Possessing urban-rural morphology and located in foothills of Northern Mountains of Alborz, Shemiranat is known as the Garden city of Tehran. Its urban fabric is a mixture of modern and traditional style. Meanwhile the Tehran master plan (2011) perspective (TMP information is produced by consulting engineering companies under government surveillance), proposes this wealthy and populated area as a tourism spot with natural and historic potential. Shemiranat acts as one of primary focal points of Tehran, particularly attracting both mountain climbers and shoppers at the weekends. The area has been exposed to urban accelerated alterations, driven both by capitalism (privatizing public spaces) and by government policies (car-oriented policies).

The purpose of this paper is to recognize sociofugal attributes of Shemiranat urban spaces by examining spatial structure and people behavior patterns, to discuss them in terms of sociopetal framework and eventually to propose suitable strategies for the area using the AIDA method.

The case study

Tehran is the capital of Iran and its largest city. It has both natural and built features. There are many urban human scale spaces in the historical central part of Tehran and Shemiranat.

Shemiranat was assigned as the No.1 urban area by Tehran municipality divisions with Tajrish Sq. as the area's central and primary urban space. Possessing urban-rural morphology and located in foothills of Northern Mountains of Alborz, Shemiranat is known as the Garden city of Tehran. Its urban fabric is a mixture of modern and traditional style. Meanwhile the Tehran master plan (2011) perspective (TMP information is produced by consulting engineering companies under government surveillance), proposes this wealthy and populated area as a tourism spot with natural and historic potential. Shemiranat acts as one of primary focal points of Tehran, particularly attracting both mountain climbers and shoppers at the weekends. The area has been exposed to urban accelerated alterations, driven both by capitalism (privatizing public spaces) and by government policies (car-oriented policies).

Figure 2: Case study location and important spots

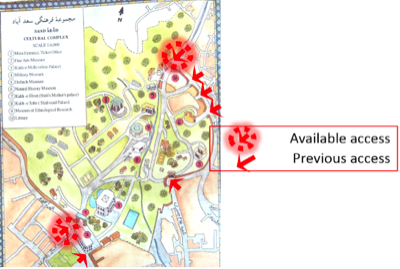

As portrayed in Figure 2, there are a range of substantial urban hubs in the area, making Shemiranat of multiple importance.

The area containing Tajrish Bridge and surrounding neighborhood centers once served as a context for people's gathering/ meeting point, including a place for holding ceremonies. According to TMP (2016) the area currently has lost its previous sociopetal characteristics and has transformed to a vehicle-led place.

While most of people in Tehran go about their everyday life by vehicles, neither spatial structure nor space elements provide a context for socialization. Shemiranat is on a reverse path towards becoming a sociofugal space. The government can act to hinder or support this trend. For example, policies such as privatizing major public attractions, and pro-car slogans such as, “A car for an Iranian” can have an impact on opportunities to socialize in urban spaces.

The paper aims at investigating relation of people's behavior and the spatial structure of Tajrish square by observation and the space syntax method, and then propose ideal scenarios for future developments to deliver sociopetal features.

Methodology

The study of social and behavioral patterns in urban spaces may be achieved through different means. Some common approaches include survey and diary of activities, video recording and simulation. In addition the observation of spaces can be fixed or varied. For example one can follow a person’s activity patterns within period of time, with a fixed set of people and with their spaces varying according to their preferences. A similar method was carried out by Appleyard (1979). Another method employed by Whyte (1980) is the so called “documenting with photography through time” in which a camera is fixed in a fixed space for variable time period. In this case the users vary. Varied users in a fixed space brings a focus on the social relationships from the individual perspective (Lang: 1987). Space Syntax is another tool, intended to anticipate people's movement/behavior through spatial network analysis. The method mostly relies on a 2D environment and needs to be complemented by observational or other methods (Diewald: 2016).

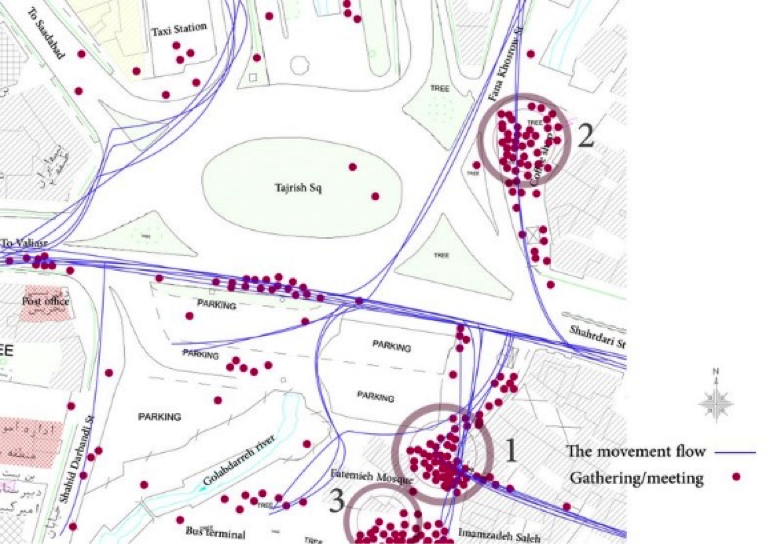

In this paper, the data were collected, by tracking human behaviour in Tajrish Square through observing, locating and recording every random individual on the map, and pedestrian flow was obtained in Tajrish Square over five different time periods per day for six weekdays for each sidewalk (proposed by Hillier et al. 1993) between 13-19 May 2016. The repeated behavioural tracking of Tajrish Square with different events and activities were then compared with space syntax results in both Global and local scales to increase accuracy of the collected data.

In an analytical-descriptive way, the discussion interprets the correlation of spatial structure and people's behavior in terms of a sociopetal framework to elucidate significant sociopetal obstacles. Finally, optimized scenarios were proposed with the least incompatibility (Analysis of Interconnected Decision Areas methodology, or AIDA) to sociopetal attributes of Shemiranat.

Results and discussion

The spatial structure of the street network is basically the primary determinant of movement and movement is the lifeblood of the city and creates the dense patterns of human contact. In this paper, observation of pedestrian behavior together with space syntax analysis could drive us toward data interpretation within the delineated perception-need framework.

Vehicles create crowding with narrowing of pedestrian flow

Vehicle-led development is the very first issue that comes to the eye as the main cause for increasing and narrowing pedestrian flow in public spaces. As an area characteristic, vehicle congestion nearer the most important tourist hubs of the area was observed (SaadAbad complex, Dr. Hesabi museum, and Zahiroddole tomb). However this was not the case for Imamzadeh Saleh (religious center) near Tajrish Square. These sociofugal-influencing factors could perhaps be linked to government policy “A car for an Iranian” and the government's tendency to prioritize the preservation of religious tourism hubs. This phenomenon declines spatial integration as space syntax analysis implies.

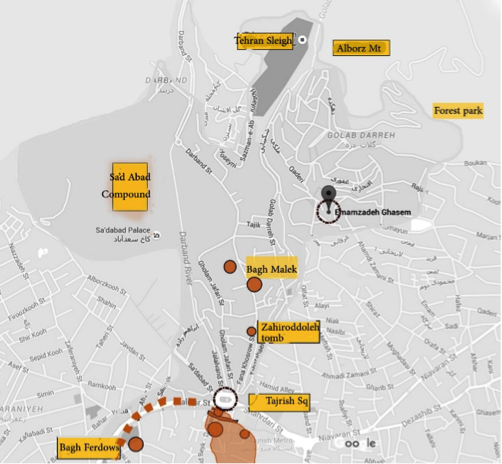

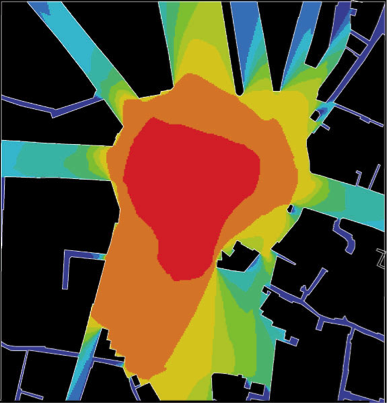

In strategic scale ,as Global axial map shows (Figure 3), Shahrdari Street has the greatest amount of integration with the most linear movements and consequently economic activities located there (as space syntax theory anticipates). This street connects two focal points of area: Tajrish and Bahonar Square. The street continues to Valieaser Street. with most luxury shops and the second highest amount of integration.

The area containing Tajrish Bridge and surrounding neighborhood centers once served as a context for people's gathering/ meeting point, including a place for holding ceremonies. According to TMP (2016) the area currently has lost its previous sociopetal characteristics and has transformed to a vehicle-led place.

While most of people in Tehran go about their everyday life by vehicles, neither spatial structure nor space elements provide a context for socialization. Shemiranat is on a reverse path towards becoming a sociofugal space. The government can act to hinder or support this trend. For example, policies such as privatizing major public attractions, and pro-car slogans such as, “A car for an Iranian” can have an impact on opportunities to socialize in urban spaces.

The paper aims at investigating relation of people's behavior and the spatial structure of Tajrish square by observation and the space syntax method, and then propose ideal scenarios for future developments to deliver sociopetal features.

Methodology

The study of social and behavioral patterns in urban spaces may be achieved through different means. Some common approaches include survey and diary of activities, video recording and simulation. In addition the observation of spaces can be fixed or varied. For example one can follow a person’s activity patterns within period of time, with a fixed set of people and with their spaces varying according to their preferences. A similar method was carried out by Appleyard (1979). Another method employed by Whyte (1980) is the so called “documenting with photography through time” in which a camera is fixed in a fixed space for variable time period. In this case the users vary. Varied users in a fixed space brings a focus on the social relationships from the individual perspective (Lang: 1987). Space Syntax is another tool, intended to anticipate people's movement/behavior through spatial network analysis. The method mostly relies on a 2D environment and needs to be complemented by observational or other methods (Diewald: 2016).

In this paper, the data were collected, by tracking human behaviour in Tajrish Square through observing, locating and recording every random individual on the map, and pedestrian flow was obtained in Tajrish Square over five different time periods per day for six weekdays for each sidewalk (proposed by Hillier et al. 1993) between 13-19 May 2016. The repeated behavioural tracking of Tajrish Square with different events and activities were then compared with space syntax results in both Global and local scales to increase accuracy of the collected data.

In an analytical-descriptive way, the discussion interprets the correlation of spatial structure and people's behavior in terms of a sociopetal framework to elucidate significant sociopetal obstacles. Finally, optimized scenarios were proposed with the least incompatibility (Analysis of Interconnected Decision Areas methodology, or AIDA) to sociopetal attributes of Shemiranat.

Results and discussion

The spatial structure of the street network is basically the primary determinant of movement and movement is the lifeblood of the city and creates the dense patterns of human contact. In this paper, observation of pedestrian behavior together with space syntax analysis could drive us toward data interpretation within the delineated perception-need framework.

Vehicles create crowding with narrowing of pedestrian flow

Vehicle-led development is the very first issue that comes to the eye as the main cause for increasing and narrowing pedestrian flow in public spaces. As an area characteristic, vehicle congestion nearer the most important tourist hubs of the area was observed (SaadAbad complex, Dr. Hesabi museum, and Zahiroddole tomb). However this was not the case for Imamzadeh Saleh (religious center) near Tajrish Square. These sociofugal-influencing factors could perhaps be linked to government policy “A car for an Iranian” and the government's tendency to prioritize the preservation of religious tourism hubs. This phenomenon declines spatial integration as space syntax analysis implies.

In strategic scale ,as Global axial map shows (Figure 3), Shahrdari Street has the greatest amount of integration with the most linear movements and consequently economic activities located there (as space syntax theory anticipates). This street connects two focal points of area: Tajrish and Bahonar Square. The street continues to Valieaser Street. with most luxury shops and the second highest amount of integration.

Figure 3: Axial map of Shemiranat (left) and spatial integration map (right)

The higher the integration, the warmer the color (more opportunity for socialization and walkability)

The higher the integration, the warmer the color (more opportunity for socialization and walkability)

Shemiranat |

Minimum |

Average |

Maximum |

Connectivity |

0 |

2.53333 |

19 |

Integration (HH) |

0.2108 |

0.8404 |

1.5569 |

Mean depth |

1 |

9.0333 |

15.2354 |

The axial maps demonstrate the most congested axes, embracing the most movement behavior in the area; observation shows that this movement mostly for the purpose of getting to the metro station at Bahonar Square, the bus terminal at Tajrish Square and for shopping. North-south alleys are the most integrated spaces after Shariati and Valiasr. Darband Street and Fanakhosro are the paths that are usually selected by mountain climbers and other tourists and native residents as walking route; these paths have more vegetation characteristics and less vehicle traffic. This is the case when Metro Tajrish is considered as a journey origin and northern attractions (Alborz Mt. Golabbdarreh, Forest park etc.) as destination. As angular and metric segment analysis anticipate, Darband is of the least distance and is mostly used for “through-movement” path and for Fnakhosro with bus terminal as origin and Zahirroddoleh, Tehran sleight, Imamzadeh Ghasem and etc. as hubs.

General social activities in an area may be reduced by isolation of spaces or privatization. On the contrary, spatial structure can act as a potential to integrate focal spaces and create a communal spaces (through-movement), (Abbaszadegan, 2002).

Strategically, the most spatial integration is found at the center of Shemiranat with Tajrish Square acting as a focal point for the area. However the spatial connectivity between Tajrish Square and other attracting public points such as Sa'ad Abad and Dr. Hessabi complexes is reduced, either associated with privatizing Sa’ad Abad and Bagh Ferdows by government, or by spatial transformations (Figure 4) and spatial integration shows that these areas experience fewer than average spatial activities (Integration 0.63).

General social activities in an area may be reduced by isolation of spaces or privatization. On the contrary, spatial structure can act as a potential to integrate focal spaces and create a communal spaces (through-movement), (Abbaszadegan, 2002).

Strategically, the most spatial integration is found at the center of Shemiranat with Tajrish Square acting as a focal point for the area. However the spatial connectivity between Tajrish Square and other attracting public points such as Sa'ad Abad and Dr. Hessabi complexes is reduced, either associated with privatizing Sa’ad Abad and Bagh Ferdows by government, or by spatial transformations (Figure 4) and spatial integration shows that these areas experience fewer than average spatial activities (Integration 0.63).

Figure 4: Spatial transformation of Sa'ad Abad complex (source: TMP 2011)

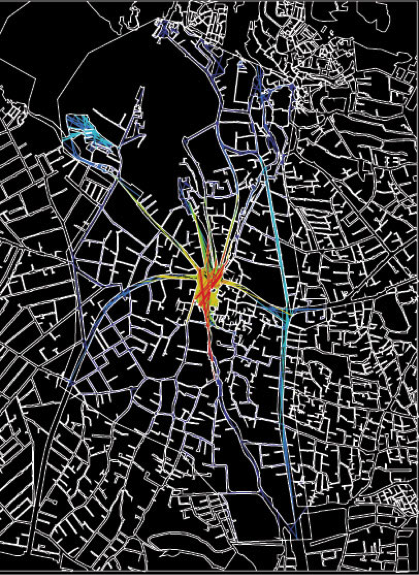

Isovist is a sector in space syntax that strongly correlates with people field of view in space, their perception toward spaces and consequently their tendency toward socialization in urban spaces. As is shown in the Tajrish neighborhood area, visibility graph analysis (Isovist), varies between 2 and 14386 with the middle of Tajrish square having the maximum amount (high vehicle congestion) and the southern part of the square (near Imamzadeh Saleh and the bus station) the second highest. (Figure 5)

Figure 5: Visual graph analysis for Tajrish neighborhood

Warmer colors show higher attitude toward gathering/socialization

Warmer colors show higher attitude toward gathering/socialization

Tajrish neighborhood |

Minimum |

Average |

Maximum |

Connectivity |

2 |

3569.72 |

14386 |

Isovist max radial |

5017.23 |

2640249 |

699502 |

Isovist min radial |

0.0325 |

7344 |

58702 |

Meanwhile Tajrish has long been a place for people to gather and enjoy sightseeing around the Golabdarreh River. As observed, most gathering/socializing activities in Tajrish occur near Bazaar Tajrish, northeast coffee shops and Imamzadeh Saleh. The southern part of Tajrish, at the river bed, experiences the least gathering and movement activities despite Isovist anticipation. This is particularly the case at night, perhaps associated with poor lighting and being known as a place for crime (safety and security components of the Lang model).

Comparing people behavior with spatial structure, Bazaar Tajrish embraces the most gathering/socialization points as observed and illustrated in Figure 6. The Bazaar is located between the two next most congested places and experiences through movement traffic between the northeast coffee shops and Imamzadeh Saleh. The place is the historic Bazaar of Tajrish and characterized by congested traditional retailers. This place provides no spatial gathering provisions (lighting, seating places etc.); however it has an attractive spatial element (commercial axis) and is located in through movement (placed between coffee shops and Imamzadeh bus terminal and Metro Station). Other Tajrish immediate spaces mostly act as transient routes (affirmed by Gehl model).

Comparing people behavior with spatial structure, Bazaar Tajrish embraces the most gathering/socialization points as observed and illustrated in Figure 6. The Bazaar is located between the two next most congested places and experiences through movement traffic between the northeast coffee shops and Imamzadeh Saleh. The place is the historic Bazaar of Tajrish and characterized by congested traditional retailers. This place provides no spatial gathering provisions (lighting, seating places etc.); however it has an attractive spatial element (commercial axis) and is located in through movement (placed between coffee shops and Imamzadeh bus terminal and Metro Station). Other Tajrish immediate spaces mostly act as transient routes (affirmed by Gehl model).

Figure 6: Pedestrian activity in Tajrish Square

The second most congested area, where the northeast coffee shops are located, are an important gathering point despite less pedestrian flow. The attractions of this area are neither traditional nor religious. Having more people meeting is perhaps due to spatial provision for seating places, enabling people to pause and watch for a while. The third gathering point is Imamzadeh Saleh, a religious place used for prayers during the day and night. Regardless of having spatial provisions (lighting, vegetation and opening) the place experiences less meeting and movement, perhaps due to less integration to Tajrish Square as shown in the spatial integration figures.

Figure 7: Local spatial integration analysis for Tajrish neighborhood

Tajrish neighborhood |

Minimum |

Average |

Maximum |

Connectivity |

2 |

545.858 |

2995 |

Integration (HH) |

0.9963 |

3.2105 |

5.6388 |

Mean depth |

2.9506 |

4.8719 |

12.0392 |

Local spatial integration of space syntax revealed that Saadabad Street has high spatial integration and people movement. This axis is mostly dedicated to urban coarse grains such as governmental buildings, and is congested with vehicles in a truly attractive tourism area, with no gathering/socializing points. The area has notable spatial character, however lacks essential uses and provokes sociofugal features according to the defined framework.

Figure 8: Visual graph analysis for Tajrish Square

Tajrish Square |

Minimum |

Average |

Maximum |

Connectivity |

8 |

30475.5 |

47254 |

Isovist max radial |

2.8670 |

265.641 |

377.702 |

Isovist min radial |

0.0002 |

17.1879 |

69.8219 |

Bahonar Square also plays an important role in the framework area. The most activities are located next to the metro station with most of coffee shops and traditional retailers being located there. There is another flow tendency from Bahonar square toward Darband St.

“To movement” is a factor in space syntax that is essential for important points of cities (cultural, historical and natural areas) as a whole to gain visitors and make places to socialize. When it comes to the Tajrish area, to-movement factor is not supported by public transportation especially for Bagh Ferdows and Sa'ad Abad complexes that don’t take even through-movement. This is weakening the possibility of socialization in these areas of Shemiranat.

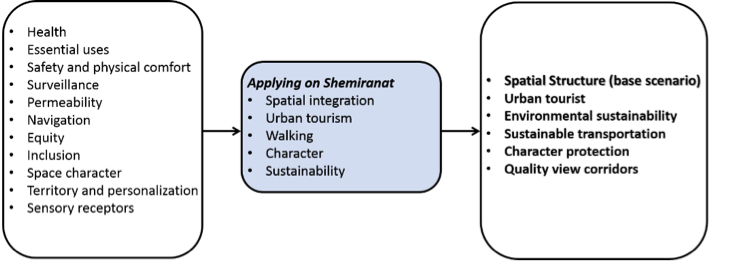

Adopting AIDA technique for future strategies

The strategic choice of approach is based on the principle that planning is a continuous process involving the evaluation of possibilities against desirability: any process of choice, state Friend and Jessop, will become a process of planning (or strategic choice) if the selection of current action is made after a formulation and comparison of possible solutions over a wider field of decisions relating to certain anticipated as well as current situations. This process will have to work in a cyclical manner so as to take account of past decisions and to allow decision makers to become familiar with the problems in question through successive round of definition, comparison. In this respect it is important to ensure that the uncertainties with which planning will always be confronted are not left out of consideration, but are taken instead as a starting-point for evaluation. The fact that the selection of action takes place within a wider field of choice implies that decisions concerning certain problems or phenomena will be influenced by decisions concerning other problems and phenomena. The Analysis of Interconnected Decision Areas (AIDA) technique can be used to make these interrelationships clear. AIDA is to a large extent a graphic technique which generates solutions in situations where a great number of possible combinations of separated choices have to be taken into accounts (Dekker et al., 1978, 149). Scenario elements for Shemiranat are gathered based on sociopetal framework and its factors (Figure 9)

“To movement” is a factor in space syntax that is essential for important points of cities (cultural, historical and natural areas) as a whole to gain visitors and make places to socialize. When it comes to the Tajrish area, to-movement factor is not supported by public transportation especially for Bagh Ferdows and Sa'ad Abad complexes that don’t take even through-movement. This is weakening the possibility of socialization in these areas of Shemiranat.

Adopting AIDA technique for future strategies

The strategic choice of approach is based on the principle that planning is a continuous process involving the evaluation of possibilities against desirability: any process of choice, state Friend and Jessop, will become a process of planning (or strategic choice) if the selection of current action is made after a formulation and comparison of possible solutions over a wider field of decisions relating to certain anticipated as well as current situations. This process will have to work in a cyclical manner so as to take account of past decisions and to allow decision makers to become familiar with the problems in question through successive round of definition, comparison. In this respect it is important to ensure that the uncertainties with which planning will always be confronted are not left out of consideration, but are taken instead as a starting-point for evaluation. The fact that the selection of action takes place within a wider field of choice implies that decisions concerning certain problems or phenomena will be influenced by decisions concerning other problems and phenomena. The Analysis of Interconnected Decision Areas (AIDA) technique can be used to make these interrelationships clear. AIDA is to a large extent a graphic technique which generates solutions in situations where a great number of possible combinations of separated choices have to be taken into accounts (Dekker et al., 1978, 149). Scenario elements for Shemiranat are gathered based on sociopetal framework and its factors (Figure 9)

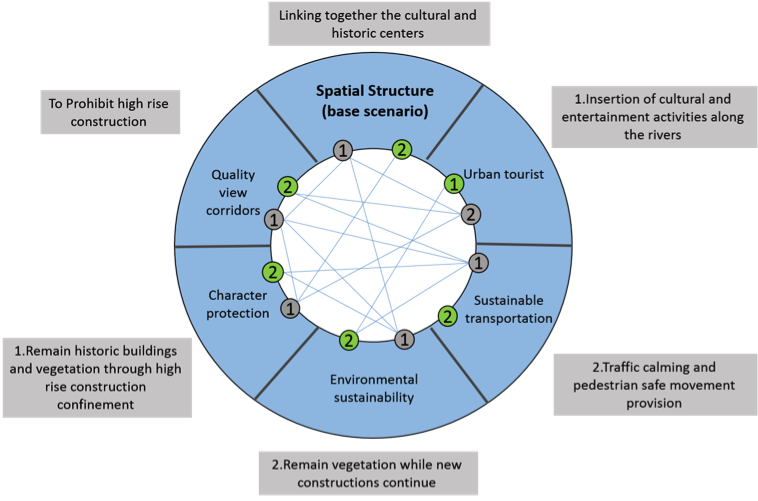

Figure 9: Shemiranat future development scenarios

Scenarios and Objectives (* = choice)

Spatial Structure (base scenario) |

1. To provide conjunction of commercial, cultural and natural centers 2. Linking together the cultural and historic centers * |

Urban tourist |

1. Insertion of cultural and entertainment activities along the rivers * 2. Natural tourist improvement with focus on rivers and Mt climbing |

Environmental sustainability |

1. To limit new constructions in vicinity of public/private green areas 2. Remain vegetation while new constructions continue * |

Sustainable transportation |

1. Developing connected pedestrian routs along with public transport expansion 2. Traffic calming and pedestrian safe movement provision * |

Character protection |

1. Remain historic buildings and vegetation through high rise construction confinement * 2. Historic character improvement by inspiring new buildings with native models |

Quality view corridors |

1. Place confinement for high rise buildings throughout the area 2. To prohibit high rise construction * |

Afterwards, the scenarios were put into an option graph (Figure 10). Those scenarios with less incompatibility (fewer attached lines) will be the optimum choices to increase the sociopedal opportunities for Shemiranat. A scenario element can be seen as a problem or phenomenon concerning the area and for which two mutually exclusive options stand open with regard to future development.

Achieved goals (objectives) matrix was used to assess and select the superior scenario. Based on scenario options and with regard to listed objectives, the spatial structure (base scenario) is offered:"Spatial structure of Shemiranat links cultural and historical areas strongly together, the area having sustainable transportation and respects on-foot pedestrians via traffic calming and provision of safe paths. The area is a tourist place and its rivers act as the lifeblood of Shemiranat, equipped with entertainment and cultural activities for all. People will experience a unique sight inside the area by remaining rural-urban character and buildings and vegetation throughout the area”.

Achieved goals (objectives) matrix was used to assess and select the superior scenario. Based on scenario options and with regard to listed objectives, the spatial structure (base scenario) is offered:"Spatial structure of Shemiranat links cultural and historical areas strongly together, the area having sustainable transportation and respects on-foot pedestrians via traffic calming and provision of safe paths. The area is a tourist place and its rivers act as the lifeblood of Shemiranat, equipped with entertainment and cultural activities for all. People will experience a unique sight inside the area by remaining rural-urban character and buildings and vegetation throughout the area”.

Figure 10: Option graph for Shemiranat - scenarios and objectives

Conclusion

As urban spaces transform to sociofugal places, psychological and physical illnesses start to rise. Sociopetal features of Shemiranat urban spaces is hindered by privatizing public spaces, car-led developments and imposing rigorous surveillance on coffee shops and other gathering places. This research showed inconsistency between space syntax results and observation methods. Most previously sociopetal urban spaces in Shemiranat now act as transient routs for pedestrians despite space syntax anticipation (3.806 integration value for Bahonar St. and Isovist 41747 for bridge area, despite lower pedestrian movement).

This study offers rays of hope with developing new methodology and results. In some cases, interview, observations or software analysis as standalone methodology may not be either practical or comprehensive, which necessitates a synthesis of methods. The new methodology of this paper associated the ideal sociopetal framework (to describe area characteristics) with observational methods (to illustrate accurate people way of socialization in urban spaces). Then the superposition of these with the space syntax anticipation revealed some inconsistency with the socio-spatial features of the area, as observed and contributed to more comprehensive analysis to the sociofugal reasons (Shahrdari St Integration value 5.386 and lower rate for gathering/meeting points based on observation). Eventually the AIDA technique was used to offer the most suitable scenarios for the future of the area, in terms of sociopetal listed factors of the framework. These findings have implications for future developments in the area.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Arash Mirzajani and Mohammadreza Alizadeh for their assistance with gathering the data. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Kamran Zekavat for comments that helped with the formation of this paper.

References

Abbas Zadegan, M. (2002). Space syntax methods in urban design, with a look to Yazd. Urban management, 9, 64-75.

Cacioppo John, Hawkley Louise (2003): Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanism, Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, volume 46, number 3 supplement (summer 2003):S39–S52 © 2003 academia library.

Carmona Matthew, Punter John (1997): The Design Dimension of Planning: Theory, content and best practice for design policies, Google books.

Carmona, Matthew (2010): Contemporary Public Space: Critique and Classification, Part One: Critique, Journal of Urban Design, 15:1, 123-148.

Cornwell Erin York, J.waite Linda (2009): Social Disconnectedness, Perceived Isolation, and Health among Older Adults, US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health.

Dekker, F. Mastop, H. Verduijn, G. Bardie, R., & Gorter, L. (1978). A Multi-level Application of Strategic Choice at the Sub-Regional Level. The Town Planning Review (TPR), 49, 149-162.

Diewald Thomas (2016): Spatial Analysis in 3D – Space Syntax, in http://thomasdiewald.com/

Edward T.Hall (1966): The hidden dimension, Anchor books, pdf document.

Gehl, Jan (1987): Life between Buildings Using Public Space, Jahad Daneshgahi publications, translated by Shima Shasti.

Hillier, B., A. Penn, J. Hanson, T. Grajewski, and J. Xu. (1993): Natural Movement: Or, Configuration and Attraction in Urban Pedestrian Movement. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design.

IICHS (2012): Institute for Iranian contemporary historical studies, Iichs.ir

Jacobs, Jane (1961): The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Vintage books, Newyork, pdf document.

Lang Jon, Moleski Walter (2010): Functionalism Revisited: Architectural Theory and Practice and the Behavioral Sciences, Google Books.

Lang Jon (1987): Creating Architectural Theory: The Role of the Behavioral Sciences in Environmental Design, translated by Alireza Einifar, Tehran University publications.

Madanipour Ali (1996): Design of Urban Space: An Inquiry into a Socio-spatial Process, University of Newcastle, Scribed, pdf document.

Mindell.S.Jennifer, Anciaes.P, Dhanani.A, Stockton.J, Jones.P, Haklay.M, Groce.N, Shaun Scholes, Vaughan.L(2017): Using triangulation to assess a suite of tools to measure community severance, Journal of Transport Geography Volume 60, April 2017, Pages 119-129.

Pakzad Jahanshah, Bozorg Hamideh (2015): Environmental psychology alphabet for designers, Armanshahr publications.

Pourjafar Mohammadreza, Amini Masoome, Hatami varzaneh Elham, Mahdavinejad Mohammadjavad (2014): Role of bazaars as a unifying factor in traditional cities of Iran: The Isfahan bazaar, Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 3, Issue 1, March 2014, Pages 10–19, Elsevier.

Schulz Norberg (1979): Genius Loci towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, Edinburg College of art library, Academia, pdf document.

TMP (2011): Tehran Master Plan, Tehran municipality.

Whyte William H. (1980): The social life of small urban spaces, Projects for public spaces, New York, Pps.org, pdf document.

As urban spaces transform to sociofugal places, psychological and physical illnesses start to rise. Sociopetal features of Shemiranat urban spaces is hindered by privatizing public spaces, car-led developments and imposing rigorous surveillance on coffee shops and other gathering places. This research showed inconsistency between space syntax results and observation methods. Most previously sociopetal urban spaces in Shemiranat now act as transient routs for pedestrians despite space syntax anticipation (3.806 integration value for Bahonar St. and Isovist 41747 for bridge area, despite lower pedestrian movement).

This study offers rays of hope with developing new methodology and results. In some cases, interview, observations or software analysis as standalone methodology may not be either practical or comprehensive, which necessitates a synthesis of methods. The new methodology of this paper associated the ideal sociopetal framework (to describe area characteristics) with observational methods (to illustrate accurate people way of socialization in urban spaces). Then the superposition of these with the space syntax anticipation revealed some inconsistency with the socio-spatial features of the area, as observed and contributed to more comprehensive analysis to the sociofugal reasons (Shahrdari St Integration value 5.386 and lower rate for gathering/meeting points based on observation). Eventually the AIDA technique was used to offer the most suitable scenarios for the future of the area, in terms of sociopetal listed factors of the framework. These findings have implications for future developments in the area.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Arash Mirzajani and Mohammadreza Alizadeh for their assistance with gathering the data. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Kamran Zekavat for comments that helped with the formation of this paper.

References

Abbas Zadegan, M. (2002). Space syntax methods in urban design, with a look to Yazd. Urban management, 9, 64-75.

Cacioppo John, Hawkley Louise (2003): Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanism, Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, volume 46, number 3 supplement (summer 2003):S39–S52 © 2003 academia library.

Carmona Matthew, Punter John (1997): The Design Dimension of Planning: Theory, content and best practice for design policies, Google books.

Carmona, Matthew (2010): Contemporary Public Space: Critique and Classification, Part One: Critique, Journal of Urban Design, 15:1, 123-148.

Cornwell Erin York, J.waite Linda (2009): Social Disconnectedness, Perceived Isolation, and Health among Older Adults, US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health.

Dekker, F. Mastop, H. Verduijn, G. Bardie, R., & Gorter, L. (1978). A Multi-level Application of Strategic Choice at the Sub-Regional Level. The Town Planning Review (TPR), 49, 149-162.

Diewald Thomas (2016): Spatial Analysis in 3D – Space Syntax, in http://thomasdiewald.com/

Edward T.Hall (1966): The hidden dimension, Anchor books, pdf document.

Gehl, Jan (1987): Life between Buildings Using Public Space, Jahad Daneshgahi publications, translated by Shima Shasti.

Hillier, B., A. Penn, J. Hanson, T. Grajewski, and J. Xu. (1993): Natural Movement: Or, Configuration and Attraction in Urban Pedestrian Movement. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design.

IICHS (2012): Institute for Iranian contemporary historical studies, Iichs.ir

Jacobs, Jane (1961): The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Vintage books, Newyork, pdf document.

Lang Jon, Moleski Walter (2010): Functionalism Revisited: Architectural Theory and Practice and the Behavioral Sciences, Google Books.

Lang Jon (1987): Creating Architectural Theory: The Role of the Behavioral Sciences in Environmental Design, translated by Alireza Einifar, Tehran University publications.

Madanipour Ali (1996): Design of Urban Space: An Inquiry into a Socio-spatial Process, University of Newcastle, Scribed, pdf document.

Mindell.S.Jennifer, Anciaes.P, Dhanani.A, Stockton.J, Jones.P, Haklay.M, Groce.N, Shaun Scholes, Vaughan.L(2017): Using triangulation to assess a suite of tools to measure community severance, Journal of Transport Geography Volume 60, April 2017, Pages 119-129.

Pakzad Jahanshah, Bozorg Hamideh (2015): Environmental psychology alphabet for designers, Armanshahr publications.

Pourjafar Mohammadreza, Amini Masoome, Hatami varzaneh Elham, Mahdavinejad Mohammadjavad (2014): Role of bazaars as a unifying factor in traditional cities of Iran: The Isfahan bazaar, Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 3, Issue 1, March 2014, Pages 10–19, Elsevier.

Schulz Norberg (1979): Genius Loci towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, Edinburg College of art library, Academia, pdf document.

TMP (2011): Tehran Master Plan, Tehran municipality.

Whyte William H. (1980): The social life of small urban spaces, Projects for public spaces, New York, Pps.org, pdf document.

About the Authors

|

Shahram Taghipour was born in Shahrekord, Iran and is currently faculty and researcher at the Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord Department of Art and Architecture. He graduated in painting from Yazd university, and received his Masters degree in art from Shahed University and PhD from Science and Research University Branch Tehran. His art has been selected at the International Festival of Fajr (2012).

|

|

Milad Heidari Soureshjani was born in Shahrekord, Iran. After graduating from Shahrekord University, he is now undertaking a Masters degree at the Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord to explore his curiosity about spatial structures and their relation to people behavior, based on socio-cultural status. He has a particular interest in the study of urban form on public health and teaches urban space analysis and workshop courses.

|

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS