|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:9

|

RESEARCH

Scoping of shared spatial needs during public building use: Autism Spectrum Disorder (Sensory Overload) and Borderline Personality Disorder (Dissociation)

Maximilienne Whitby

University of New South Wales Australia

University of New South Wales Australia

Key messages for urban planning and design

Inclusive design enhances environmental competency and removes barriers to enable people to interact with their surroundings in the way they want to. Two disorders that can affect people's environmental competency are Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). This scoping study found that interpersonal interactions were a key barrier to their use of public buildings. Affordances considered to benefit people with ASD and BPD may include nooks, niches and private seating areas; territorial control; good visibility of wayfinding signage; a range of lighting and materials to enable choice by user;

Inclusive design enhances environmental competency and removes barriers to enable people to interact with their surroundings in the way they want to. Two disorders that can affect people's environmental competency are Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). This scoping study found that interpersonal interactions were a key barrier to their use of public buildings. Affordances considered to benefit people with ASD and BPD may include nooks, niches and private seating areas; territorial control; good visibility of wayfinding signage; a range of lighting and materials to enable choice by user;

- Nooks, niches and other semi private seating areas with good visual and territorial control. These areas should have good visibility of wayfinding signage.

- Range of different lighting conditions and material pallets in different seating areas to allow for a greater range of choice by user.

- Handrails in non-heavy traffic circulator areas as an alternative to navigating dense crowds.

- Acoustic isolation between zones of function, with some directional noise information available within each zone. (Someone walking towards etc.)

Introduction

A key factor in a person's use of a space is their environmental competence and confidence (Imrie & Hall, 2001). Environmental competency and person–environment fit are ways of describing a person’s ability (or lack thereof) to interact with their surroundings in the way they want to. This environmental autonomy is important for quality of life and access to opportunities for building social capital, those social interactions that are mutually beneficial to participants, and are tied to a person’s sense of belonging to community. Without environmental competency, people may become socially isolated. (Ben-Sasson, Cermak, Orsmond, Tager-Flushberg, Kadlec, & Carter, 2008, Whitby, 2017).

The World Health Organisation identifies the environment as exerting a significant and meaningful impact on disability (World Health Organisation, 2001). Environmental competency can therefore have a significant enabling or disabling impact on people with different needs. One way in which this can be mitigated is through a reduction of barriers to a person interacting with their surroundings. Francois Chapireau (2005) describes environmental barriers as “the gap between capacity and performance … created by the environment.” Inclusive design recognizes that people have a range of spatial needs, and designs can reduce barriers to allow more people to use their built environments independently, safely and comfortably. For the purposes of this paper, inclusive design will be a blanket term which intends to incorporate and build upon the ideas of universal and accessible design, encompassing elements of: design for disability, design for accessibility, barrier-free design etc.)

Two disorders that can affect people's environmental competency are Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) refers to a group of conditions characterized by impairments of reciprocal social interaction, verbal and non-verbal communication, as well as a preference for repetitive, stereotyped activities, behaviors and interests.” (ICF, 2017) Some people with ASD experience sensory overload, where one or more of the five senses over-processes information. This can become overwhelming and impact environmental competence. Davidson and Henderson (2017) identify that the range of sensory functioning and types of perception within ASD experiences are very broad, and can include a mix of so called high and low function presentation of one or more sensory aspects. This is inclusive of sensory overload. (Ben-Sasson, Cermak, Orsmond, Tager-Flushberg, Kadlec, & Carter 2008, Cascio, 2010). Designing for Autism Spectrum Disorders (Gaines, Bourne, Pearson, & Kleibrink, 2016) highlights the topical and growing field of designing for Autistic Spectrum Disorders and examines the existing knowledge base of built environment research and ASD. This work recognises that “although the surrounding environment has such a strong influence over people with ASD, there is very little information on how to design spaces for these individuals.” Moreover, the knowledge that does exist is primarily based on home and education environments, and the scope of transferability to other building use scenarios remains unclear.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is “A mental disability typified by a disordered behavior pattern that is marked by unstable, intense emotions and mood with symptoms including instability in interpersonal relationships and self-image, fears of abandonment, and impulsive or unpredictable behavior.” (First & Tasman, 2004). Many people with BPD experience dissociation, the separation of aspects of personality or behaviour from active consciousness. This can feel like being 'out of body,' or not being anywhere. Part of this is thought to be a flight response to trigger or processing overload.

Access to public built environments is important for opportunities to build social capital, which impacts mental health and quality of life (Giles-Corti, 2006). Since both disorders involve significant difficulties with interpersonal interactions (Gill & Warburton, 2014, Smith, 2008), this might indicate shared barriers to using public buildings. A better understanding of barriers to public building use for these two target demographics has the potential to improve quality of life, as well as to identify scope for examining those barriers and spatial needs within the context of other building typologies that may be important for people with ASD or BPD, designers and planners, and also for healthcare and social work practitioners. And yet the author found few existing built environment research or case studies relating to ASD, and none relating to BPD.

This research uses methodologies informed by built environment research traditions (Preiser, Rabinowitz, & White, 1988) (Groat & Wang, 2013) with an emphasis on knowledge exchange and values based research methods (Preiser, Rabinowitz, & White, 1988). In investigating spatial needs and barriers, the author applies the lived experiences of people with ASD and BPD to the field of inclusive design, exploring the scope of potential shared spatial needs and barriers, specifically in regards to sensory overload and dissociation. This scoping research, as part of a larger project to meet the requirements for the author's honours thesis in Architectural Studies, provides a preliminary insight into inclusive design targets and opportunities to increase environmental competency for people with these disorders.

Methods

Mixed methodology qualitative methods were used: a source review was conducted to identify existing knowledge and to inform the direction of further investigation via semi structured interviews. Each interview also had a card sort component in order to gain further insights.

Source review

A preliminary source review was conducted using a coding matrix to identify themes, and knowledge gaps. Sources were derived from key word searches and snowballing (where an original source leads to a secondary source, such as a book cited within a journal article). A coding matrix was used to identify themes and track theoretical saturation. (Bryman 2016) This was important in a scoping study to identify themes and knowledge gaps, and ensure a thorough description of the relationships between concepts and content across multiple sources.

Recruitment of participants

Recruitment for the project was undertaken in compliance with UNSW HREC ethics clearance (HC16689) using the following inclusion criteria:

People of all genders who are over 18

AND Have a diagnosis by a health professional of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and experience sensory overload

OR Have a diagnosis by a health professional of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and experience dissociation.

Respondents were self-selecting. All respondents were contacted, however due to the low response rate and fluctuating functionality of respondents only two interviews were conducted; 1 participant with ASD (code name PICARD) and 1 with BPD (code name SULU). As this project was both exploratory and qualitative in nature, sample size was not a priority.

Semi-structured Interviews

Interviews were conducted to gain more insight into the gaps identified during the source review, and to identify areas with scope for meaningful future research. Interviews were used because “an interview gives people the opportunity to tell their stories in their own words… and can be empowering as it recognizes people as experts of their own experiences” (Sommer & Sommer, 2002), which is in the spirit of both knowledge exchange, and inclusive design. Interview questions were designed to increase in specificity and application to case studies. Bryman (2016) identifies semi structured interviews as a more flexible data collection method which facilitates emergence, and recommends the use of probes and follow up questions in order to draw out detail. The interview questions were intended to help frame semi structured conversation and as such were the starting point for the interviews. They acted as a tool to help the participant think about the card sort images. Additionally, prompts and probes were used to tease out responses to the outlining questions. This included during the card sort. A "looping back around" technique was used in order to keep the discussion laid back and as not to exert pressure on responses and to allow for reflection and emergence in the responses. The same questions and types of prompts were used with each participant in order to be able to make comparisons.

Card sort

A card sort exercise was conducted during each interview. Card sort images were selected to represent 4 case study locations within the Sydney Opera House, a local public building. Card sorts are good for understanding how a participant conceptualizes and sorts information (Rosenfeld & Moreville, 2002). In this instance a closed card sort was used (Spencer, 2009). The card sort was conducted in a very relaxed way with the interviewer adopting a more casual tone and in their own words saying: “I just have a couple of pictures here, would you be able to order them in a way that makes sense to you. For example: from most likely to least likely to use etc.” The participant was then asked to talk about what helped them make those decisions.

Prompting for descriptive answers was framed in a way that did not unduly pressure the participant. Images for the card sort (Figure 1) were selected to show existing seating, lighting and material pallet of the case study areas. Some of them contain people using the space to help the participant imagine a comparison to their own behavior. All case study locations were part of the same larger circulation space adjacent to the concert hall of the Sydney Opera House. The interviewer was familiar with the typical crowd patterns of use in the case study locations shown in the card sort in order to answer any questions, as well as to probe the participant. For example: “would it change the way you used that [affordance] if there were people standing next to it and looking out the window?”

A key factor in a person's use of a space is their environmental competence and confidence (Imrie & Hall, 2001). Environmental competency and person–environment fit are ways of describing a person’s ability (or lack thereof) to interact with their surroundings in the way they want to. This environmental autonomy is important for quality of life and access to opportunities for building social capital, those social interactions that are mutually beneficial to participants, and are tied to a person’s sense of belonging to community. Without environmental competency, people may become socially isolated. (Ben-Sasson, Cermak, Orsmond, Tager-Flushberg, Kadlec, & Carter, 2008, Whitby, 2017).

The World Health Organisation identifies the environment as exerting a significant and meaningful impact on disability (World Health Organisation, 2001). Environmental competency can therefore have a significant enabling or disabling impact on people with different needs. One way in which this can be mitigated is through a reduction of barriers to a person interacting with their surroundings. Francois Chapireau (2005) describes environmental barriers as “the gap between capacity and performance … created by the environment.” Inclusive design recognizes that people have a range of spatial needs, and designs can reduce barriers to allow more people to use their built environments independently, safely and comfortably. For the purposes of this paper, inclusive design will be a blanket term which intends to incorporate and build upon the ideas of universal and accessible design, encompassing elements of: design for disability, design for accessibility, barrier-free design etc.)

Two disorders that can affect people's environmental competency are Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) refers to a group of conditions characterized by impairments of reciprocal social interaction, verbal and non-verbal communication, as well as a preference for repetitive, stereotyped activities, behaviors and interests.” (ICF, 2017) Some people with ASD experience sensory overload, where one or more of the five senses over-processes information. This can become overwhelming and impact environmental competence. Davidson and Henderson (2017) identify that the range of sensory functioning and types of perception within ASD experiences are very broad, and can include a mix of so called high and low function presentation of one or more sensory aspects. This is inclusive of sensory overload. (Ben-Sasson, Cermak, Orsmond, Tager-Flushberg, Kadlec, & Carter 2008, Cascio, 2010). Designing for Autism Spectrum Disorders (Gaines, Bourne, Pearson, & Kleibrink, 2016) highlights the topical and growing field of designing for Autistic Spectrum Disorders and examines the existing knowledge base of built environment research and ASD. This work recognises that “although the surrounding environment has such a strong influence over people with ASD, there is very little information on how to design spaces for these individuals.” Moreover, the knowledge that does exist is primarily based on home and education environments, and the scope of transferability to other building use scenarios remains unclear.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is “A mental disability typified by a disordered behavior pattern that is marked by unstable, intense emotions and mood with symptoms including instability in interpersonal relationships and self-image, fears of abandonment, and impulsive or unpredictable behavior.” (First & Tasman, 2004). Many people with BPD experience dissociation, the separation of aspects of personality or behaviour from active consciousness. This can feel like being 'out of body,' or not being anywhere. Part of this is thought to be a flight response to trigger or processing overload.

Access to public built environments is important for opportunities to build social capital, which impacts mental health and quality of life (Giles-Corti, 2006). Since both disorders involve significant difficulties with interpersonal interactions (Gill & Warburton, 2014, Smith, 2008), this might indicate shared barriers to using public buildings. A better understanding of barriers to public building use for these two target demographics has the potential to improve quality of life, as well as to identify scope for examining those barriers and spatial needs within the context of other building typologies that may be important for people with ASD or BPD, designers and planners, and also for healthcare and social work practitioners. And yet the author found few existing built environment research or case studies relating to ASD, and none relating to BPD.

This research uses methodologies informed by built environment research traditions (Preiser, Rabinowitz, & White, 1988) (Groat & Wang, 2013) with an emphasis on knowledge exchange and values based research methods (Preiser, Rabinowitz, & White, 1988). In investigating spatial needs and barriers, the author applies the lived experiences of people with ASD and BPD to the field of inclusive design, exploring the scope of potential shared spatial needs and barriers, specifically in regards to sensory overload and dissociation. This scoping research, as part of a larger project to meet the requirements for the author's honours thesis in Architectural Studies, provides a preliminary insight into inclusive design targets and opportunities to increase environmental competency for people with these disorders.

Methods

Mixed methodology qualitative methods were used: a source review was conducted to identify existing knowledge and to inform the direction of further investigation via semi structured interviews. Each interview also had a card sort component in order to gain further insights.

Source review

A preliminary source review was conducted using a coding matrix to identify themes, and knowledge gaps. Sources were derived from key word searches and snowballing (where an original source leads to a secondary source, such as a book cited within a journal article). A coding matrix was used to identify themes and track theoretical saturation. (Bryman 2016) This was important in a scoping study to identify themes and knowledge gaps, and ensure a thorough description of the relationships between concepts and content across multiple sources.

Recruitment of participants

Recruitment for the project was undertaken in compliance with UNSW HREC ethics clearance (HC16689) using the following inclusion criteria:

People of all genders who are over 18

AND Have a diagnosis by a health professional of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and experience sensory overload

OR Have a diagnosis by a health professional of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and experience dissociation.

Respondents were self-selecting. All respondents were contacted, however due to the low response rate and fluctuating functionality of respondents only two interviews were conducted; 1 participant with ASD (code name PICARD) and 1 with BPD (code name SULU). As this project was both exploratory and qualitative in nature, sample size was not a priority.

Semi-structured Interviews

Interviews were conducted to gain more insight into the gaps identified during the source review, and to identify areas with scope for meaningful future research. Interviews were used because “an interview gives people the opportunity to tell their stories in their own words… and can be empowering as it recognizes people as experts of their own experiences” (Sommer & Sommer, 2002), which is in the spirit of both knowledge exchange, and inclusive design. Interview questions were designed to increase in specificity and application to case studies. Bryman (2016) identifies semi structured interviews as a more flexible data collection method which facilitates emergence, and recommends the use of probes and follow up questions in order to draw out detail. The interview questions were intended to help frame semi structured conversation and as such were the starting point for the interviews. They acted as a tool to help the participant think about the card sort images. Additionally, prompts and probes were used to tease out responses to the outlining questions. This included during the card sort. A "looping back around" technique was used in order to keep the discussion laid back and as not to exert pressure on responses and to allow for reflection and emergence in the responses. The same questions and types of prompts were used with each participant in order to be able to make comparisons.

Card sort

A card sort exercise was conducted during each interview. Card sort images were selected to represent 4 case study locations within the Sydney Opera House, a local public building. Card sorts are good for understanding how a participant conceptualizes and sorts information (Rosenfeld & Moreville, 2002). In this instance a closed card sort was used (Spencer, 2009). The card sort was conducted in a very relaxed way with the interviewer adopting a more casual tone and in their own words saying: “I just have a couple of pictures here, would you be able to order them in a way that makes sense to you. For example: from most likely to least likely to use etc.” The participant was then asked to talk about what helped them make those decisions.

Prompting for descriptive answers was framed in a way that did not unduly pressure the participant. Images for the card sort (Figure 1) were selected to show existing seating, lighting and material pallet of the case study areas. Some of them contain people using the space to help the participant imagine a comparison to their own behavior. All case study locations were part of the same larger circulation space adjacent to the concert hall of the Sydney Opera House. The interviewer was familiar with the typical crowd patterns of use in the case study locations shown in the card sort in order to answer any questions, as well as to probe the participant. For example: “would it change the way you used that [affordance] if there were people standing next to it and looking out the window?”

Figure 1: Images used for card sort

Results

Source evaluation

The source evaluation fell into three loose primary clusters: Personal Accounts, Medical (including Psychiatric, Psychological and self-help), and Built Environment. This allowed for the identification of similarities in content covered by the Personal and Medical sources for Autism Spectrum Disorder and how they differ in focus from the Built Environment Autism Spectrum Disorder sources. This is likely indicative of the type of information that is useful for the intended audience of the sources, and illustrates the importance of built environment research of demographics with health related barriers and spatial needs.

Card sort

The card sort ordering task resulted in preferences as illustrated by Figure 2 and Figure 3. Both participants expressed a significant preference for case study location 2, and were able to talk about what aspects of the spaces shown in the card sort were barriers or spatial needs relative to their own lived experience. If there had been larger sample sizes, comparative studies within and between demographics could have been conducted. However, in this instance, the card sort was more effective as a tool for helping the participants to talk about their own preferences such as handrails or seating options. This is why the card sort results were combined with the interview before being coded using the established coding matrix.

Source evaluation

The source evaluation fell into three loose primary clusters: Personal Accounts, Medical (including Psychiatric, Psychological and self-help), and Built Environment. This allowed for the identification of similarities in content covered by the Personal and Medical sources for Autism Spectrum Disorder and how they differ in focus from the Built Environment Autism Spectrum Disorder sources. This is likely indicative of the type of information that is useful for the intended audience of the sources, and illustrates the importance of built environment research of demographics with health related barriers and spatial needs.

Card sort

The card sort ordering task resulted in preferences as illustrated by Figure 2 and Figure 3. Both participants expressed a significant preference for case study location 2, and were able to talk about what aspects of the spaces shown in the card sort were barriers or spatial needs relative to their own lived experience. If there had been larger sample sizes, comparative studies within and between demographics could have been conducted. However, in this instance, the card sort was more effective as a tool for helping the participants to talk about their own preferences such as handrails or seating options. This is why the card sort results were combined with the interview before being coded using the established coding matrix.

Figure 2: Card sort order by subject PICARD, ranked most - least preferred

Figure 3: Card sort order by subject SULU, ranked most - least preferred

Interviews

The interview transcriptions were coded for themes using the existing coding matrix, before being sorted into three broad categories:

These were then distilled using qualitative content analysis and checked against tables derived from the source review as a form of triangulation.

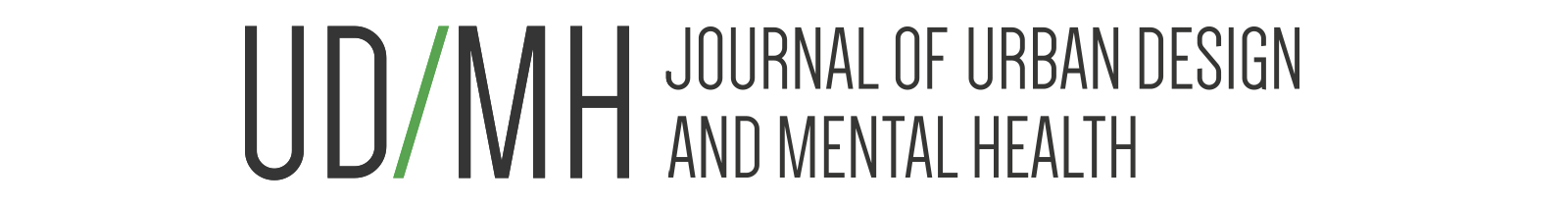

Coding

The coding matrix from the interviews was combined with the coding matrix from the source review to produce the composite coding matrix below (Figure 4) to assess if any of the gaps identified by the source review matrix were able to be better contextualised during the interviews. This also allows for rapid identification of further theoretical saturation, triangulation and facilitates a more in depth comparison and contrast analysis. Data from the interviews was grouped with the corresponding target demographic sources. It is important to note that all yellow highlighted point of non-saturation corresponding to micro facial cues was separately evidenced in additional sources in the literature review during the first half of the thesis, and is in fact an existing recognised barrier for both target demographics.

The interview transcriptions were coded for themes using the existing coding matrix, before being sorted into three broad categories:

- Barriers (sensory overload/dissociation)

- Barriers (general)

- Spatial needs.

These were then distilled using qualitative content analysis and checked against tables derived from the source review as a form of triangulation.

Coding

The coding matrix from the interviews was combined with the coding matrix from the source review to produce the composite coding matrix below (Figure 4) to assess if any of the gaps identified by the source review matrix were able to be better contextualised during the interviews. This also allows for rapid identification of further theoretical saturation, triangulation and facilitates a more in depth comparison and contrast analysis. Data from the interviews was grouped with the corresponding target demographic sources. It is important to note that all yellow highlighted point of non-saturation corresponding to micro facial cues was separately evidenced in additional sources in the literature review during the first half of the thesis, and is in fact an existing recognised barrier for both target demographics.

Figure 4. Coding Matrix - Source Review and Interviews

Green - Theoretical saturation by inclusion of interview data (evidence exists; data do not reveal new theoretical insights)

Yellow - No theoretical saturation (potential theoretical insights; continued need for further investigation)

Pink - Instances of emergence as a result of the interviews (theoretical insights; expansion of existing knowledge)

P - interview with PICARD; S - interview with SULU

Green - Theoretical saturation by inclusion of interview data (evidence exists; data do not reveal new theoretical insights)

Yellow - No theoretical saturation (potential theoretical insights; continued need for further investigation)

Pink - Instances of emergence as a result of the interviews (theoretical insights; expansion of existing knowledge)

P - interview with PICARD; S - interview with SULU

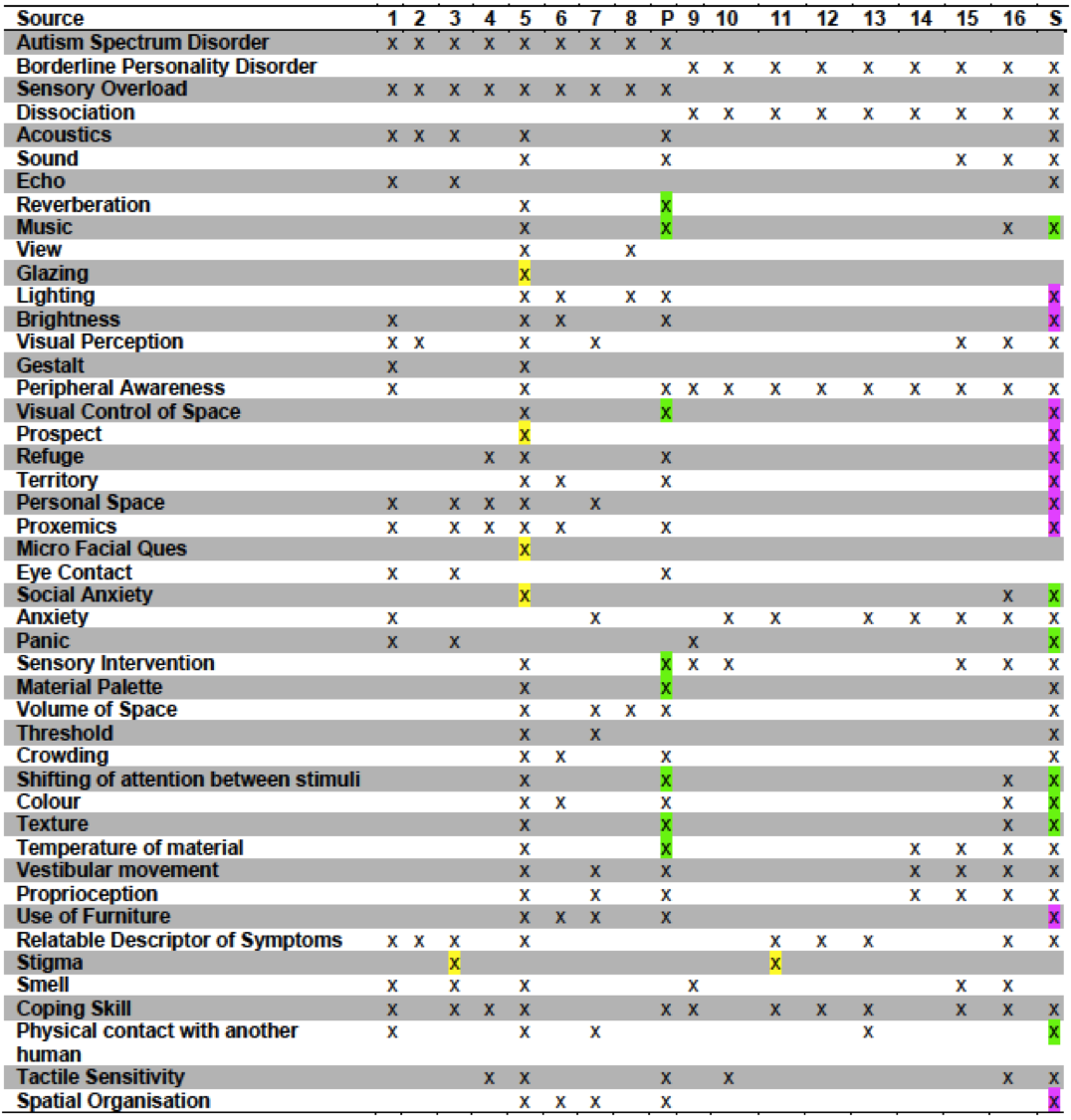

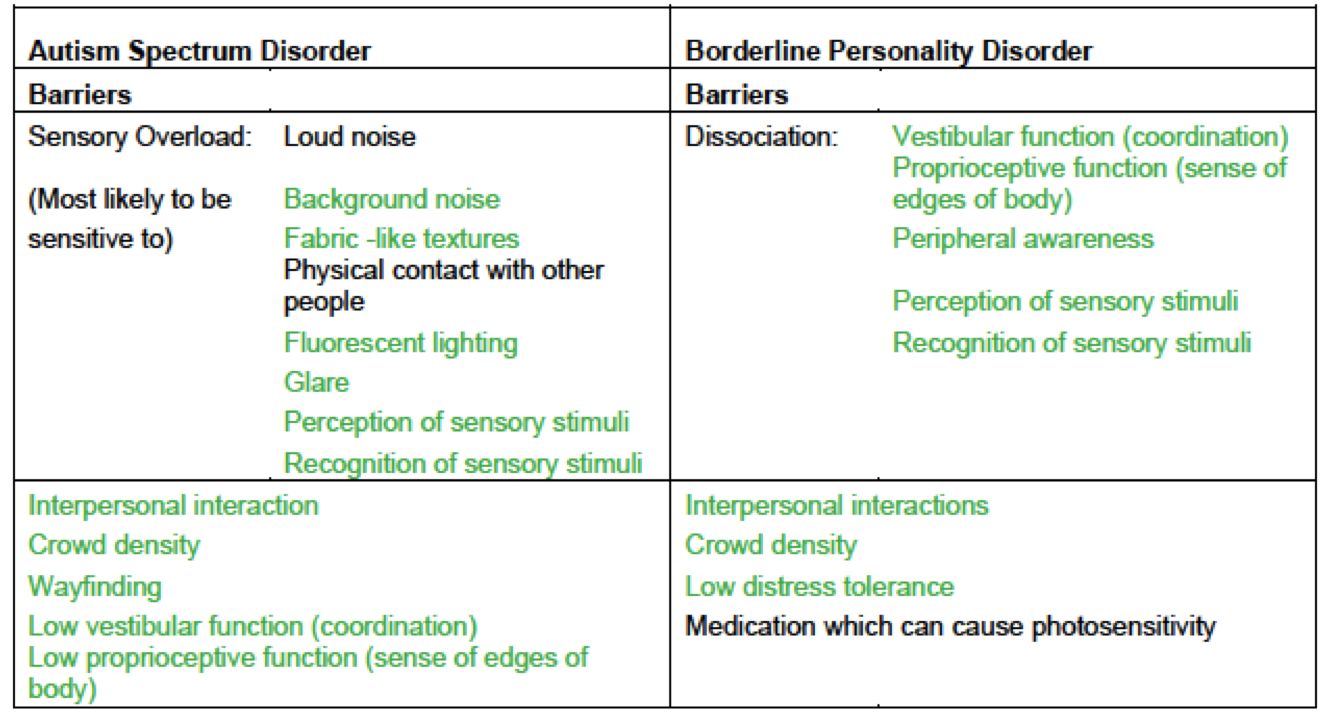

Tables of barriers and

spatial needs derived from the source review were then checked against the

interview transcripts for convergence and triangulation. Convergence is

indicated by green text in the tables below. Black text denotes information

identified in the source review that is neither confirmed nor challenged by the

interviews. Divergence would be indicated in red however there were no

incidences where this occurred.

Figure 5:

Convergence between methods – Barriers

Figure 6: Convergence between methods - spatial needs

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

More research is needed beyond the scope of this project. However, the key findings both specific to each target demographic, and to the project as a whole are outlined below:

Key findings in Autism Spectrum Disorder and public building use

Key findings in Borderline Personality Disorder and public building use

Potential complementary needs

More research is needed beyond the scope of this project. However, the key findings both specific to each target demographic, and to the project as a whole are outlined below:

Key findings in Autism Spectrum Disorder and public building use

- Some existing research on ASD is likely transferable to public building use.

- More emphasis is needed on coping with the built environment as it is encountered (not adapted).

- Prospect and Refuge are potentially very important.

Key findings in Borderline Personality Disorder and public building use

- Existing research on BPD is not adequately descriptive.

- There is a strong emphasis on relationship to tactile experience of the built environment.

- Proprioceptive and vestibular function may be a key barrier.

- Visual control of territory may be very important.

Potential complementary needs

-

May rely on forms of

tactile wayfinding.

-

Nooks and niches

are probably the best places for targeted affordances.

-

Stairs may represent particular challenges (related to proprioceptive function and anxiety about low function).

-

Desire for personal

territory and visual control of territory was strong in this sample.

-

Barriers and spatial needs not

tied specifically to sensory overload or dissociation may continue to have a

noticeable impact during episodes of sensory overload or dissociation and need

to be accounted for.

DISCUSSION

It should be noted that because the interview data was intended to confirm and contextualise the source review data, and the project as a whole was scoping, theoretical saturation was not a particular concern. Given that the entire project was exploratory in nature, the card sort component of the interviews can be deemed particularly successful. This is attributed less to the ordering exercise, but rather as an aid to conceptualisation of spatial use which allowed participants to be more descriptive about their own relationship with the built environment.

It was important to explore which of the components of the different person-environment theories are not applicable to either or both target demographics. Solid confirmation of this lies beyond the scope of investigation but there are indicators which suggest the possibility of such an impact, and as such need consideration and discussion in relation to the data sets.

Aspects of non-typical interpersonal interaction behaviours are a significant barrier for both target demographics and may have an impact on the validity of proxemics theory in relation to the target demographics. It is possible that this has a flow on effect to the applicability of defensible space, personal space and behaviour sets theories. It is also probable that social dominance expressed as territorial behaviour is miss-read or not registered at all by the target demographics, and that this may have behavioural response and psychological/psychosocial implications.

This could be especially important in transitory areas of public buildings and the inherent entitlement and territorial behaviours of both general population and target demographic users. Both have paid for a slice of the territorial pie. This may translate to an amplification of perceived stigmatization of target demographics ‘I have also paid to be here, I have a right to continue being here’, especially when behaviour is not an actual risk to other or self. (This is where training of responders can make a difference to actual vs perceived risk assessment and response management.)

In light of the research, three aspects of the existing theoretical framework identified in the source review component can be considered to be supported:

Whereas the following considerations may indicate further research is needed or that more complex relationships are at play:

Specifically in regards to the spatial needs of Borderline Personality Disorder, a substantial need for further investigation exists. Additionally; the following can be considered important non-definitive findings for both demographics:

It is reasonable to assume that the following spatial needs would be of significant benefit to both of the target demographics and that public buildings should strongly consider implementing the following affordances:

An aspect of the methodology of note is the difference between the effectiveness of interview questions combined with card sort images versus without card sort images, and the richness and depth of data facilitated by the card sort. This may be due to the challenges in articulating what is working and what is not working for a participant and their use of the built environment. It is recommended that future research takes this into account.

It is possible that the explorations and investigations of this project yields data which may be relevant for other user groups, especially those with anxiety or social interaction components. Non-neurotypical environmental perception may also apply to target demographics with depressive and manic traits, as well as target demographics with differing forms of sensory overload.

The application of findings during the design process may also be of future interest and it is hoped that the proposed research contributes to an increase dialogue within the profession around design for mental and developmental disability. Of significant concern is the undercurrent of stigma surrounding the target demographics. This project intends to contribute in a meaningful way to the dialogue within the profession around respecting and valuing the lived experience of end users of buildings.

It was important to explore which of the components of the different person-environment theories are not applicable to either or both target demographics. Solid confirmation of this lies beyond the scope of investigation but there are indicators which suggest the possibility of such an impact, and as such need consideration and discussion in relation to the data sets.

Aspects of non-typical interpersonal interaction behaviours are a significant barrier for both target demographics and may have an impact on the validity of proxemics theory in relation to the target demographics. It is possible that this has a flow on effect to the applicability of defensible space, personal space and behaviour sets theories. It is also probable that social dominance expressed as territorial behaviour is miss-read or not registered at all by the target demographics, and that this may have behavioural response and psychological/psychosocial implications.

This could be especially important in transitory areas of public buildings and the inherent entitlement and territorial behaviours of both general population and target demographic users. Both have paid for a slice of the territorial pie. This may translate to an amplification of perceived stigmatization of target demographics ‘I have also paid to be here, I have a right to continue being here’, especially when behaviour is not an actual risk to other or self. (This is where training of responders can make a difference to actual vs perceived risk assessment and response management.)

In light of the research, three aspects of the existing theoretical framework identified in the source review component can be considered to be supported:

- Interpersonal interactions are a key barrier to use of public buildings by both target demographics.

- Physical aspects of the built environment can impact the way users from the target demographics experience the built environment.

- Some built environment theories need to be re-examined for applicability to the target demographics.

Whereas the following considerations may indicate further research is needed or that more complex relationships are at play:

- Extent of similarity of symptomatic presentation of sensory overload in adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

- Larger scale Borderline Personality Disorder - Built Environment research especially relating to proprioceptive and vestibular function, material palette preferences and sensory therapies, photosensitivity impact due to medication.

- Possible link between sensory overload and dissociation as it presents as a symptom of Borderline Personality Disorder.

Specifically in regards to the spatial needs of Borderline Personality Disorder, a substantial need for further investigation exists. Additionally; the following can be considered important non-definitive findings for both demographics:

- De-escalation spaces are likely to be the most flexible affordance with the largest positive impact on target demographics user’s ability to engage with their spatial surroundings.

- Users from both target demographics may be at higher risk for falls and this should be considered when implementing targeted affordances.

It is reasonable to assume that the following spatial needs would be of significant benefit to both of the target demographics and that public buildings should strongly consider implementing the following affordances:

- Nooks, niches and other semi private seating areas with good visual and territorial control. These areas should have good visibility of wayfinding signage.

- Range of different lighting conditions and material pallets in different seating areas to allow for a greater range of choice by user.

- Handrails in non-heavy traffic circulator areas as an alternative to navigating dense crowds.

- Acoustic isolation between zones of function, with some directional noise information available within each zone. (Someone walking towards etc.)

An aspect of the methodology of note is the difference between the effectiveness of interview questions combined with card sort images versus without card sort images, and the richness and depth of data facilitated by the card sort. This may be due to the challenges in articulating what is working and what is not working for a participant and their use of the built environment. It is recommended that future research takes this into account.

It is possible that the explorations and investigations of this project yields data which may be relevant for other user groups, especially those with anxiety or social interaction components. Non-neurotypical environmental perception may also apply to target demographics with depressive and manic traits, as well as target demographics with differing forms of sensory overload.

The application of findings during the design process may also be of future interest and it is hoped that the proposed research contributes to an increase dialogue within the profession around design for mental and developmental disability. Of significant concern is the undercurrent of stigma surrounding the target demographics. This project intends to contribute in a meaningful way to the dialogue within the profession around respecting and valuing the lived experience of end users of buildings.

Limitations

Data from the interviews can only be viewed as non-definitive. This is due to the wide range of symptom presentation in adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder, the small sample size, and the lack of similar studies involving Borderline Personality Disorder for comparison. However, lived experience accounts helped to contextualize the source review data, and as such the interviews can be deemed a successful contribution to the overall exploratory study of barriers and spatial needs encountered by adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder during Sensory Overload and adults with Borderline Personality Disorder during Dissociation, when using public buildings.

Data from the interviews can only be viewed as non-definitive. This is due to the wide range of symptom presentation in adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder, the small sample size, and the lack of similar studies involving Borderline Personality Disorder for comparison. However, lived experience accounts helped to contextualize the source review data, and as such the interviews can be deemed a successful contribution to the overall exploratory study of barriers and spatial needs encountered by adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder during Sensory Overload and adults with Borderline Personality Disorder during Dissociation, when using public buildings.

References

Aguirre, B, & Galen, G. (2013). Mindfulness for borderline personality disorder, Oakland, California: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Aguirre, B, & Galen, G. (2015). Coping with BPD. Oakland, California: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Aguirre, B.(2014). Borderline Personality Disorder in Adolescents, Beverly, Massachusetts: Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc.

Alissierrr. (video, 21 Aug 2016). BPD Chat - dissociation in BPD, anxiety, depression, etc, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016. Viewed 1 October 2016

Balf, G. (video, 1 July 2013). BPD-related cognitive-perceptual difficulties and challenges in their diagnosis and treatment, 9th Annual Yale NEA – BPD Conference 10 May 2013; Yale University, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016.

Beaver, C. (May/June 2010). Designing for Autism, SEN Magazine 46.

Ben-Sasson, A., Cermak, S., Orsmond, G., Tager-Flushberg, H., Kadlec, M., & Carter, A. (2008). Sensory clusters of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(8).

Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods, Fifth Edition New York: Oxford University Press.

Cascio, C. (2010). Somatosensory processing in neurodevelopmental disorders. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 2.

Chapireau, Francois. (2005). The Environment in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. pp307

Connell, Bettye Rose, Mike Jones, Ron Mace, Jim Mueller, Abir Mullick, Elaine Ostroff, Jon Sanford, Ed Steinfeld, Molly Story, and Gregg Vanderheiden . The Principles of Universal Design, Version 2.0. North Carolina State University, NC: The Center for Universal Design, 1997.

Davidson & Henderson in Bates, C., Imrie, R., & Kullman, K. (2017) Care in Design, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

First, Michael, and Allan Tasman Eds (2004) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual -IV-TR. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Fruzzetti, A. (video, 7 February 2014) DBT Treatment - "What works for Borderline Personality Disorder?, Hebrew University of Jerusalem 23 Mar 2014; Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016.

Gaines, K., Bourne,A., Pearson, M., & Kleibrink, M. (2016). Designing for Autism Spectrum Disorders, New York: Routledge.

Giles-Corti, B. (2006). “The impact of urban form on public health.” paper prepared for the 2006 Australian State of the Environment Committee, Canberra: Department of the Environment and Heritage.

Gill. D, & Warburton. W. “An Investigation of the Biosocial Model of Borderline Personality Disorder.” Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 70(9), (2014): 866–873, accessed May 2, 2016, doi: 10.1002/jclp.22074.

Groat, L. & Wang. D. (2013). Architectural Research Methods, New Jersey: Wiley.

Henry, C. (19 October 2011) “Designing for Autism: Spatial Considerations”, ArchDaily. viewed 3 June 2016.

Henry, C. (26 October 2011). Designing for Autism: Lighting, ArchDaily. viewed 3 June 2016

Hinkle, V. (2008). Card-sorting: What you need to know about analyzing and interpreting card sorting results. Usability News, 10 (2), 1 – 6.

Imrie, R, & Hall. P. (2001). Inclusive Design: Designing and Developing Accessible Environment, London: Spon Press.

Morton, K. (video, 2 June 2013) Dissociation, what is it, how do we deal with it? Mental Health with Kati Morton, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016.

Rosenfeld, L. and Morville, P. (2002). Information Architecture for the World Wide Web: Designing Large Scale Web Sites. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly & Associates.

Smith, S. “The relationship among adaptive behavior, Empathizing, systemizing, sensory issues and the Temperament of adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2008.

Sommer. R., & Sommer, B. (2002). A Practical Guide to Behavioral Research: Tools and Techniques, New York: Oxford University Press. pp 113

Spencer, D. (2009). Card sorting: Designing usable categories. Brooklyn, NY: Rosenfield Media.

The National Autistic Society. (video, 25 April 2016). Kerry’s Story, Youtube: Viewed 1 October 2016.

The National Autistic Society. (video, 25 April 2016). Will’s Story, Youtube: Viewed 1 October 2016. Viewed 1 October 2016.

Whitby, M. (2017). Making Space: Exploring the barriers and spatial needs encountered by adults with a lived experience of Autism Spectrum Disorder (Sensory Overload) and adults with a lived experience of Borderline Personality Disorder (Dissociation) when using public buildings, Honours Thesis UNSW. (First Class)

Wolfgang, P., Rabinowitz. H., & White. E. (1988). Post-Occupancy Evaluation, USA: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

World Health Organization. (1992) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2001). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wright, M. (video, 28 Oct 2015). Dissociative state and Psychosis, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016.

Aguirre, B, & Galen, G. (2013). Mindfulness for borderline personality disorder, Oakland, California: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Aguirre, B, & Galen, G. (2015). Coping with BPD. Oakland, California: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Aguirre, B.(2014). Borderline Personality Disorder in Adolescents, Beverly, Massachusetts: Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc.

Alissierrr. (video, 21 Aug 2016). BPD Chat - dissociation in BPD, anxiety, depression, etc, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016. Viewed 1 October 2016

Balf, G. (video, 1 July 2013). BPD-related cognitive-perceptual difficulties and challenges in their diagnosis and treatment, 9th Annual Yale NEA – BPD Conference 10 May 2013; Yale University, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016.

Beaver, C. (May/June 2010). Designing for Autism, SEN Magazine 46.

Ben-Sasson, A., Cermak, S., Orsmond, G., Tager-Flushberg, H., Kadlec, M., & Carter, A. (2008). Sensory clusters of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(8).

Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods, Fifth Edition New York: Oxford University Press.

Cascio, C. (2010). Somatosensory processing in neurodevelopmental disorders. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 2.

Chapireau, Francois. (2005). The Environment in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. pp307

Connell, Bettye Rose, Mike Jones, Ron Mace, Jim Mueller, Abir Mullick, Elaine Ostroff, Jon Sanford, Ed Steinfeld, Molly Story, and Gregg Vanderheiden . The Principles of Universal Design, Version 2.0. North Carolina State University, NC: The Center for Universal Design, 1997.

Davidson & Henderson in Bates, C., Imrie, R., & Kullman, K. (2017) Care in Design, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

First, Michael, and Allan Tasman Eds (2004) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual -IV-TR. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Fruzzetti, A. (video, 7 February 2014) DBT Treatment - "What works for Borderline Personality Disorder?, Hebrew University of Jerusalem 23 Mar 2014; Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016.

Gaines, K., Bourne,A., Pearson, M., & Kleibrink, M. (2016). Designing for Autism Spectrum Disorders, New York: Routledge.

Giles-Corti, B. (2006). “The impact of urban form on public health.” paper prepared for the 2006 Australian State of the Environment Committee, Canberra: Department of the Environment and Heritage.

Gill. D, & Warburton. W. “An Investigation of the Biosocial Model of Borderline Personality Disorder.” Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 70(9), (2014): 866–873, accessed May 2, 2016, doi: 10.1002/jclp.22074.

Groat, L. & Wang. D. (2013). Architectural Research Methods, New Jersey: Wiley.

Henry, C. (19 October 2011) “Designing for Autism: Spatial Considerations”, ArchDaily. viewed 3 June 2016.

Henry, C. (26 October 2011). Designing for Autism: Lighting, ArchDaily. viewed 3 June 2016

Hinkle, V. (2008). Card-sorting: What you need to know about analyzing and interpreting card sorting results. Usability News, 10 (2), 1 – 6.

Imrie, R, & Hall. P. (2001). Inclusive Design: Designing and Developing Accessible Environment, London: Spon Press.

Morton, K. (video, 2 June 2013) Dissociation, what is it, how do we deal with it? Mental Health with Kati Morton, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016.

Rosenfeld, L. and Morville, P. (2002). Information Architecture for the World Wide Web: Designing Large Scale Web Sites. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly & Associates.

Smith, S. “The relationship among adaptive behavior, Empathizing, systemizing, sensory issues and the Temperament of adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2008.

Sommer. R., & Sommer, B. (2002). A Practical Guide to Behavioral Research: Tools and Techniques, New York: Oxford University Press. pp 113

Spencer, D. (2009). Card sorting: Designing usable categories. Brooklyn, NY: Rosenfield Media.

The National Autistic Society. (video, 25 April 2016). Kerry’s Story, Youtube: Viewed 1 October 2016.

The National Autistic Society. (video, 25 April 2016). Will’s Story, Youtube: Viewed 1 October 2016. Viewed 1 October 2016.

Whitby, M. (2017). Making Space: Exploring the barriers and spatial needs encountered by adults with a lived experience of Autism Spectrum Disorder (Sensory Overload) and adults with a lived experience of Borderline Personality Disorder (Dissociation) when using public buildings, Honours Thesis UNSW. (First Class)

Wolfgang, P., Rabinowitz. H., & White. E. (1988). Post-Occupancy Evaluation, USA: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

World Health Organization. (1992) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2001). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wright, M. (video, 28 Oct 2015). Dissociative state and Psychosis, Youtube: viewed 1 October 2016.

About the Author

|

Maximilienne Whitby is a PhD student at the University of New South Wales in Sydney Australia; she researches, writes and works within the fields of Accessible Design for Neurodiversity, Evidence-Based Design and Person-Environment. She is passionately engaged in promoting equity and diversity through her community work at a faculty, university, and wider community level.

@_thinblacklines |

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS