|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:11

|

ANALYSIS

Planning and Building Healthy Communities for Mental Health

Method, findings and reflections from a recent integrative study

Greg Paine

Research Officer, City Wellbeing Program, City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales Australia

Susan Thompson

City Wellbeing Program Head, Associate Director City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales Australia

Research Officer, City Wellbeing Program, City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales Australia

Susan Thompson

City Wellbeing Program Head, Associate Director City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales Australia

Key messages for urban planning and design

- Understanding the design and management attributes needed to achieve health-supportive environments requires a broad, multi-dimensional and connected approach – which challenges the focused and sectoral orientation typical of epidemiological research and practice.

- Achieving healthy built environments includes responding to the direct experiences of residents and other users. Our research shows these experiences are expressed as connected, holistic understandings of both personal health needs and the ways in which the built environment can assist.

- Professionals charged with creating and managing cities are also residents. However they frequently forget or neglect these ‘joined-up‘ understandings – becoming silo-ed and detached, rather than networked and empathic.

- The 'pattern language' work of architect Christopher Alexander relating to the human 'felt' experience of urban environments provides a useful model to structure health-supportive environment research, and the subsequent development of findings into 'do-able' key guides for practitioners.

Introduction

This paper introduces research on Planning and Building Healthy Communities (1) that investigated the extent to which four new residential neighbourhoods support the health of residents. The study took a broad rather than sectoral approach, with the result that the findings are as much about overall ‘wellbeing’ as they are about particular health issues. As such they are also closely related to mental health.

The research was undertaken by the Healthy Built Environment Program (now City Wellbeing Program) at the University of New South Wales, Australia. The four study areas are located within or near to the Sydney metropolitan area and comprise a variety of urban configurations and residential densities. The findings and methodology are relevant to similar newly-establishing as well as established urban communities elsewhere.

Health-supportive urban environments as inter-connected, and the resolution of tensions.

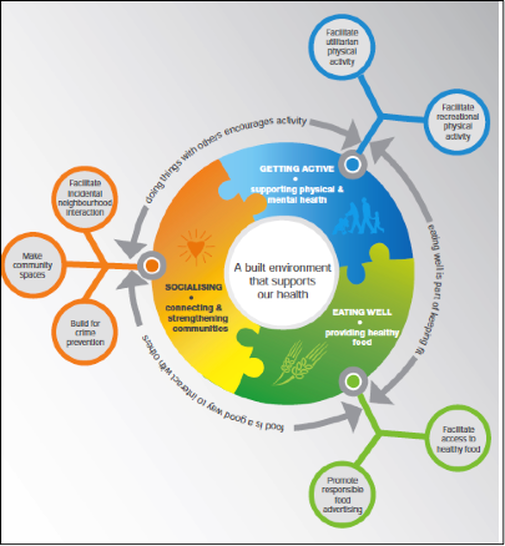

The research was largely prompted by current concerns about an ‘epidemic’ of chronic disease, including mental illness, and a growing body of research indicating the configuration and management of our urban areas plays a significant role in prompting, compounding and mitigating such diseases. A review of this research concluded that attention was needed in respect to how the environment can promote increases in three of the well-known health-supportive behaviours to reduce risk for chronic disease: physical activity, interaction – both socially and with ‘green’ environments, and consumption of fresh foods.(2) All three needs interact of course (Figure 1), and generate ‘co-benefits’. For example, and from the particular perspective of mental health, physical activity is conducive to mental wellbeing; connecting socially with others is both mentally stimulating in itself and can facilitate engagement in physical activity; good nutrition is necessary for effective brain and body function, while preparing and eating food can be a good catalyst for social interaction.

This paper introduces research on Planning and Building Healthy Communities (1) that investigated the extent to which four new residential neighbourhoods support the health of residents. The study took a broad rather than sectoral approach, with the result that the findings are as much about overall ‘wellbeing’ as they are about particular health issues. As such they are also closely related to mental health.

The research was undertaken by the Healthy Built Environment Program (now City Wellbeing Program) at the University of New South Wales, Australia. The four study areas are located within or near to the Sydney metropolitan area and comprise a variety of urban configurations and residential densities. The findings and methodology are relevant to similar newly-establishing as well as established urban communities elsewhere.

Health-supportive urban environments as inter-connected, and the resolution of tensions.

The research was largely prompted by current concerns about an ‘epidemic’ of chronic disease, including mental illness, and a growing body of research indicating the configuration and management of our urban areas plays a significant role in prompting, compounding and mitigating such diseases. A review of this research concluded that attention was needed in respect to how the environment can promote increases in three of the well-known health-supportive behaviours to reduce risk for chronic disease: physical activity, interaction – both socially and with ‘green’ environments, and consumption of fresh foods.(2) All three needs interact of course (Figure 1), and generate ‘co-benefits’. For example, and from the particular perspective of mental health, physical activity is conducive to mental wellbeing; connecting socially with others is both mentally stimulating in itself and can facilitate engagement in physical activity; good nutrition is necessary for effective brain and body function, while preparing and eating food can be a good catalyst for social interaction.

Figure 1: Matrix of a healthy built environment. (3)

This review paper however draws on another, complementary, perspective, not part of the original research. This is the work, now over some 40 years, of the architect Christopher Alexander predominantly from his time at the University of California Berkeley. Alexander was concerned about the deteriorating quality of urban living environments. He has sought to develop a process of design that would handle the growing complexity of city building without, as is too often the case, resorting to easier – but ultimately deficient – specialised and fragmented responses and processes. However, Alexander’s aspiration was far greater than such a ‘mechanical’ description might suggest. He does not talk for instance of urban areas that are merely ‘efficient’ and ‘comfortable’. Rather he sought something more substantial: those key elements of city design that will, as he put it, engender ‘life’. (4)

An important cross-disciplinary fertilisation occurred at an early stage in this work. At that time the United States National Institute for Mental Health was interested in researching the relationship between wellbeing and the design of the places where people live. This interest dove-tailed with Alexander’s quest to identify the ‘key elements’ referred to above, and the Institute provided early funding for his research.(5)

One outcome was an interesting convergence in how Alexander conceptualised problem solving, urban design issues, and personal mental and physical wellbeing. Alexander had earlier described each of the design issues he was exploring as comprising a set of tensions or forces, with subsequent design solutions being in effect the resolution of those tensions. In his words: “Forces have a characteristic pattern and the good form [ie. built environment/urban solution] is in equilibrium with the pattern, almost as if it was lying at the neutral point of a vector of a field of forces.”(6) As his work progressed, Alexander described and illustrated the experience of urban living in terms of mental wellbeing, also using similar imagery. The urban ‘life’ which he seeks is for instance defined as being when “…all our [personal] forces can move freely within us.” When this does not occur we become “bottled up”, with “a tightness about the mouth, a nervous tension in the eyes, a stiffness and a brittleness in the way we walk, the way we move”. (7) The key elements of city design Alexander defined are those things that will then release those tensions or, preferably, not give rise to their presence in the first place.

Alexander described each of these elements as design ‘patterns’, able to guide urban practitioners (whether designers, builders, policy makers or managers) in their task. Such patterns, when implemented, will result in built environments able to “…eliminate the stress cycle, release people’s natural force, and thus make room for positive forces, positive emotions, and positive human interactions to have free play.” (8) Importantly, the patterns do not describe actual designs, but rather the essential quality designs need to embody (in whatever configuration or style or preference) to achieve this objective.

By way of example (and one which is all too familiar in places with an Anglo-Saxon background) Alexander describes a situation where cafés are indoors, away from the footpath, dictated by local health regulations, based on concerns about possible food contamination. But notwithstanding this explicit health objective, Alexander contends the resultant built configuration is “dead” – it has no congruence with people’s “inner force” needs and desires. And the only way this can be maintained is through the force of law. Rather, “people want to be outdoors on a spring day, and to drink their beer or coffee in the open…watch the world go by but they are imprisoned within the café by the laws of public health. The situation is self-destroying…it is continuously creating…inner conflicts…reservoirs of stress which will, unsatisfied, soon well up like a gigantic boil and leak out in some…form of destruction….”.(9)

Alexander’s most well-known work, published in 1977, is a compendium of 253 patterns he contends are ‘life-supportive’. (10) The patterns range from the shape of a room to the whole layout of a city. They have titles like: ‘Magic of the City’ (to be within easy reach of all residents); ‘Street Café’ (where one can relax and watch the world go by); ‘Private Terrace on the Street’ (allowing a connection with passers-by while retaining domestic privacy); and ‘Six Foot Balcony’ (wide enough for a table people can sit and interact around). Combined they form a ‘pattern language’ for overall city design.

Alexander’s work has been cited as a key influence on the New Urbanism movement, and wiki technology was originally devised in part to facilitate a further aspiration of Alexander’s – that each of his patterns be available for on-going review and improvement by users’ experiences. (11)

The research process: discerning and resolving tensions.

The Planning and Building Healthy Communities study comprised three principle components:

The design and outcome of the workshop is of most interest to this paper. The design drew on an earlier visual and participatory interview tool (described in Paine, 2015(12)) to similarly work with participants to discuss in a non-confronting way personal and community issues and how they might be resolved. In the research it sought to ‘honour’ the ability of participants to know within themselves what they need to do to keep healthy (an ability which had been revealed in the interviews). The intention was to elicit responses grounded in this knowledge without being ‘mediated’ through the lens of the existing research literature (as was the case with the structure of the previous interviews in order to facilitate comparison with other studies). The different approach in the workshop also addressed the need for social research to transcend the ‘needs’, structures and biases of the researcher in order to reveal the more important needs of the (other) participants. As McKnight (1991)(13) suggests, social surveys aimed at facilitating change should seek out what the participants have to offer, rather than take a point of view of ‘offering’ something to participants. In addition, participant control and ownership (albeit to varying degrees) of the process and/or information being imparted is fundamentally consistent with the promotion of individual and community mental wellbeing.

The workshop was centred around four broad questions, to which participants were asked for at least three separate answers each written on a separate card. The first two questions asked about their own health behaviours:

The subsequent questions asked about the things which assist their health actions and aspirations:

An important cross-disciplinary fertilisation occurred at an early stage in this work. At that time the United States National Institute for Mental Health was interested in researching the relationship between wellbeing and the design of the places where people live. This interest dove-tailed with Alexander’s quest to identify the ‘key elements’ referred to above, and the Institute provided early funding for his research.(5)

One outcome was an interesting convergence in how Alexander conceptualised problem solving, urban design issues, and personal mental and physical wellbeing. Alexander had earlier described each of the design issues he was exploring as comprising a set of tensions or forces, with subsequent design solutions being in effect the resolution of those tensions. In his words: “Forces have a characteristic pattern and the good form [ie. built environment/urban solution] is in equilibrium with the pattern, almost as if it was lying at the neutral point of a vector of a field of forces.”(6) As his work progressed, Alexander described and illustrated the experience of urban living in terms of mental wellbeing, also using similar imagery. The urban ‘life’ which he seeks is for instance defined as being when “…all our [personal] forces can move freely within us.” When this does not occur we become “bottled up”, with “a tightness about the mouth, a nervous tension in the eyes, a stiffness and a brittleness in the way we walk, the way we move”. (7) The key elements of city design Alexander defined are those things that will then release those tensions or, preferably, not give rise to their presence in the first place.

Alexander described each of these elements as design ‘patterns’, able to guide urban practitioners (whether designers, builders, policy makers or managers) in their task. Such patterns, when implemented, will result in built environments able to “…eliminate the stress cycle, release people’s natural force, and thus make room for positive forces, positive emotions, and positive human interactions to have free play.” (8) Importantly, the patterns do not describe actual designs, but rather the essential quality designs need to embody (in whatever configuration or style or preference) to achieve this objective.

By way of example (and one which is all too familiar in places with an Anglo-Saxon background) Alexander describes a situation where cafés are indoors, away from the footpath, dictated by local health regulations, based on concerns about possible food contamination. But notwithstanding this explicit health objective, Alexander contends the resultant built configuration is “dead” – it has no congruence with people’s “inner force” needs and desires. And the only way this can be maintained is through the force of law. Rather, “people want to be outdoors on a spring day, and to drink their beer or coffee in the open…watch the world go by but they are imprisoned within the café by the laws of public health. The situation is self-destroying…it is continuously creating…inner conflicts…reservoirs of stress which will, unsatisfied, soon well up like a gigantic boil and leak out in some…form of destruction….”.(9)

Alexander’s most well-known work, published in 1977, is a compendium of 253 patterns he contends are ‘life-supportive’. (10) The patterns range from the shape of a room to the whole layout of a city. They have titles like: ‘Magic of the City’ (to be within easy reach of all residents); ‘Street Café’ (where one can relax and watch the world go by); ‘Private Terrace on the Street’ (allowing a connection with passers-by while retaining domestic privacy); and ‘Six Foot Balcony’ (wide enough for a table people can sit and interact around). Combined they form a ‘pattern language’ for overall city design.

Alexander’s work has been cited as a key influence on the New Urbanism movement, and wiki technology was originally devised in part to facilitate a further aspiration of Alexander’s – that each of his patterns be available for on-going review and improvement by users’ experiences. (11)

The research process: discerning and resolving tensions.

The Planning and Building Healthy Communities study comprised three principle components:

- a comprehensive audit of each neighbourhood – not simply a detached review of census, medical and Geographic Information Systems data, but pounding the footpaths, buying food in the shops, and observing how spaces are actually used;

- detailed semi-structured interviews with residents, asking about behaviours, aspirations and needs; and

- follow-up workshops with interviewees to explore in more depth what worked and what did not in terms of their health.

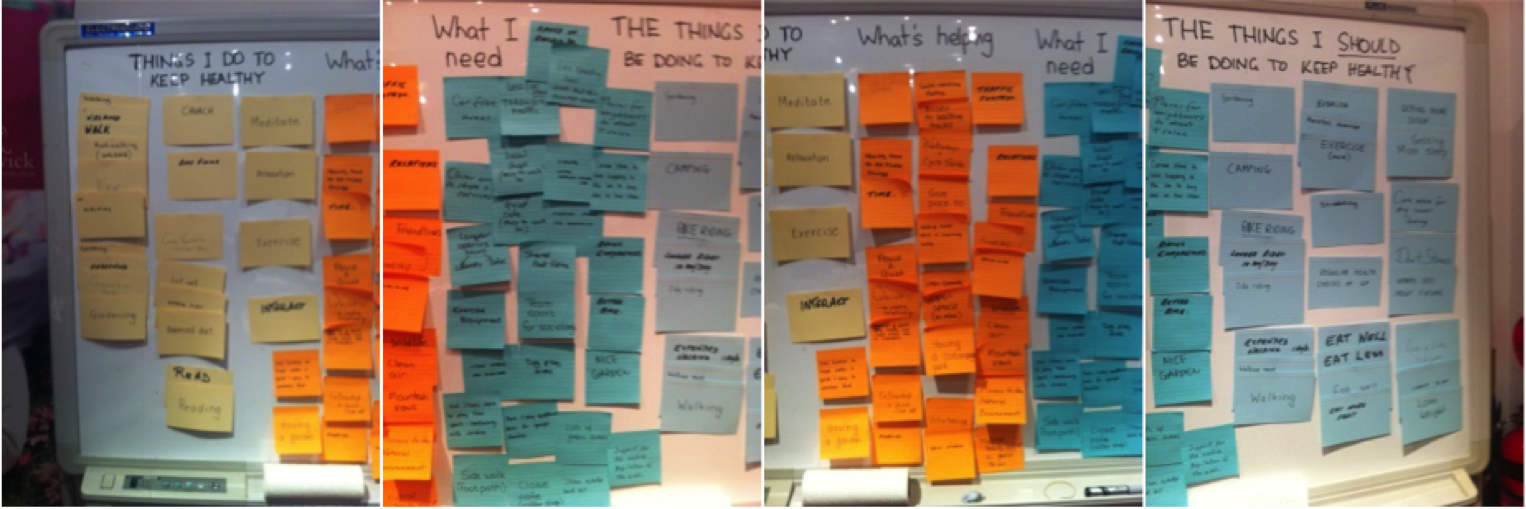

The design and outcome of the workshop is of most interest to this paper. The design drew on an earlier visual and participatory interview tool (described in Paine, 2015(12)) to similarly work with participants to discuss in a non-confronting way personal and community issues and how they might be resolved. In the research it sought to ‘honour’ the ability of participants to know within themselves what they need to do to keep healthy (an ability which had been revealed in the interviews). The intention was to elicit responses grounded in this knowledge without being ‘mediated’ through the lens of the existing research literature (as was the case with the structure of the previous interviews in order to facilitate comparison with other studies). The different approach in the workshop also addressed the need for social research to transcend the ‘needs’, structures and biases of the researcher in order to reveal the more important needs of the (other) participants. As McKnight (1991)(13) suggests, social surveys aimed at facilitating change should seek out what the participants have to offer, rather than take a point of view of ‘offering’ something to participants. In addition, participant control and ownership (albeit to varying degrees) of the process and/or information being imparted is fundamentally consistent with the promotion of individual and community mental wellbeing.

The workshop was centred around four broad questions, to which participants were asked for at least three separate answers each written on a separate card. The first two questions asked about their own health behaviours:

- What are the things I do (now) to keep healthy?

- What are the things I should be doing (but do not do) to keep healthy?

The subsequent questions asked about the things which assist their health actions and aspirations:

- What is helping me to keep healthy, now?

- What I need to keep healthy?

(Q.1) The things I do (now) to keep healthy. |

(Q.3) What is helping me to keep healthy, now. |

(Q.4) What I need to keep healthy. |

(Q.2) The things I should be doing (but do not do) to keep healthy. |

This display established a ‘dialogue space’ (occupied by Q.3 and Q.4), with the entries on either side (Q.1 and Q.2) stimulating that dialogue. Williams (2002)(14) has referred to a similar space between our ‘rational’ and ‘emotional’ minds, representing the ‘wise mind’. Alexander references a similar idea of ‘opening the joints’ of any dilemma as present in the ideas of both Plato and Lao Tze. (15) This ‘dialogue space’ is also then directly illustrative of the kind of tensions Alexander describes as apparent within both the physical urban environment and ourselves – and which need to be resolved to live effectively.

The workshop sought to mirror this conceptualisation. It enabled the participants (and the researchers) to see and discuss why for some matters the space, or ‘gap’, was ‘small’ (indicating where things worked effectively) and why for others the gap was ‘large’ (indicating things missing or needing improvement). This revealed a series of insights about health-supportive environments. The discussion was prompted by two facilitators based on the card entries and their knowledge of the localities from the on-the-ground audits and resident interviews.

The discussion was not restricted to built environment matters in order to elicit information not yet in the literature about how individuals perceive their health and associated health needs, and to reveal matters beyond merely the ‘physical’ aspects of the built environment such as the more elusive determinants of use including convenience, opening hours, availability of child-care and other ‘management’ matters (given also the potential importance of such matters had been suggested from the earlier on-ground audits and resident interviews). Further, it was hoped that more wide-ranging discussion would reveal broader cultural attitudes existing in the subject localities, which are important when designing and implementing responses relating to health-supportive behaviour.

The workshop sought to mirror this conceptualisation. It enabled the participants (and the researchers) to see and discuss why for some matters the space, or ‘gap’, was ‘small’ (indicating where things worked effectively) and why for others the gap was ‘large’ (indicating things missing or needing improvement). This revealed a series of insights about health-supportive environments. The discussion was prompted by two facilitators based on the card entries and their knowledge of the localities from the on-the-ground audits and resident interviews.

The discussion was not restricted to built environment matters in order to elicit information not yet in the literature about how individuals perceive their health and associated health needs, and to reveal matters beyond merely the ‘physical’ aspects of the built environment such as the more elusive determinants of use including convenience, opening hours, availability of child-care and other ‘management’ matters (given also the potential importance of such matters had been suggested from the earlier on-ground audits and resident interviews). Further, it was hoped that more wide-ranging discussion would reveal broader cultural attitudes existing in the subject localities, which are important when designing and implementing responses relating to health-supportive behaviour.

Figure 2: The display of participants’ completed comments cards at one of the focus groups.

The completed cards provide a ‘key word’ summary of participants’ concerns, aspirations and experiences that are transferred into an easy-to-read table (Table 1). The answers to questions (3) and (4) have now, with the other study data, been translated into recommendations for concrete actions and guidelines. The process appeared to be equally effective and instructive for the participants themselves (hence potentially generating on-going positive personal and community outcomes), as illustrated in the following comment:

"So with all the issues that have been popping out throughout this discussion, I’ve been really surprised, because I’ve stayed here for about two years, but I’ve never really thought about certain issues that we have discussed. So that’s actually pretty fascinating, for me, myself".(16)

What the participants advised.

The responses in both the individual card entries (Table 1) and the discussion transcripts confirmed the three ‘domains’ of action identified from the earlier literature (physical activity, social interaction and nutrition - see the groupings of entries in Table 1) and included, as anticipated, references to ‘management’ type matters relating to the effectiveness of the built environment features provided in each neighbourhood.

"So with all the issues that have been popping out throughout this discussion, I’ve been really surprised, because I’ve stayed here for about two years, but I’ve never really thought about certain issues that we have discussed. So that’s actually pretty fascinating, for me, myself".(16)

What the participants advised.

The responses in both the individual card entries (Table 1) and the discussion transcripts confirmed the three ‘domains’ of action identified from the earlier literature (physical activity, social interaction and nutrition - see the groupings of entries in Table 1) and included, as anticipated, references to ‘management’ type matters relating to the effectiveness of the built environment features provided in each neighbourhood.

Table 1: Participant responses on notions of health and health needs. (17)

What I do to keep healthy |

What is helping me to keep healthy (things I have now) |

What I need to keep healthy (things I do not have now) |

What I should be doing to keep healthy |

Walk / walk the dog. Tennis / golf / swim / aqua-aerobics. Run / jog. Regular exercise / pilates / gym / bodyweight exercise. Swim/aqua-aerobics. Bike riding. Play sport with my child / family. Take stairs, not the lift. Dance while doing housework. Gardening. Shop local. Use public transport. Watch what I eat / eat lots of fruit & vegetables, lean meat. Balance diet/home cooked food / not processed. Moderate intake of food. Grow own vegetables Keep busy. Interact / socialising with local community. Time with friends/family. Looking after my children. Run around with grandchildren. Try not to stress. Time to myself, space. Keep busy. Work / volunteering. Plenty of fresh air. Close windows to avoid air & noise pollution. Church. Read / crossword puzzles. Relax / meditate. Regular / sufficient sleep. Regular health checks. Kit, sew, crochet. Keep house tidy. |

Exercise / dancing / yoga classes at local centres. Walk dog in park. No car, so forced to walk. Good public transport. Bike lanes - encourage me to cycle. Nearby parks for cycling / running / jogging. Parks, playgrounds, activity centres. Local gym / pilates centre / swimming / tennis courts. Working in garden. Lots of good places to walk. Good choice of healthy food options. Not many fast food outlets (unlike previous location). The farmers market. Connecting with people when walking dog. Great communication at the park. Friends / motivation from friends / outings. Laughter / good times. Fellowship (church, club). Work / volunteering. Giving up some activities [=more time/energy]. Energy. My wife / myself. Using my brain (crosswords/ reading). Close-by bulk-bill doctor. Having a garden. Safe place to walk. Convenient shops can walk to with children’s play area Easy access. BBQ, picnic area. Good public facilities (library, markets). Parks (clears the mind) / open character / lots of nature areas. Peace and quiet / little traffic noise. The locality of where I live. The layout – openness, not congested, water feature. Good internet access [less stress]. |

Cheaper gyms / swimming pool (hydrotherapy). Close-by swimming pool. Personal trainers in park. Yoga, dance classes. More parks/playgrounds/ activity centres. Fitness equipment. Cycling tracks. Shaded areas / seats. Flat, pleasant walking path. Control dog poo in park. Corner store to save taking car to buy one or two items Cycling companions. Oval/tennis courts to play team sports, track field – especially with children. Safer areas to walk around. Close-by reasonable-priced supermarket / fresh food shops. Variety of cafes/restaurants Team sports for socialising. Places for neighbours to meet / relax / walk to. Some community events. Social network club. Ability to get to know neighbours in apartments. Address over-crowding (rubbish, parking, traffic). No noise / air pollution. More personal space. Privacy in my unit. Self-control. Money. Ability to practice a hobby. More time. Being in less pain. Not aware of community / exercise groups. Recent violent event-now sacred to go out at night. Repair damaged footpaths. Local doctor / chemist. Better transportation. Longer opening hours (library, cafes). Streets that do not encourage speeding. Nice garden. Lots of green areas / clean water, air / dog play areas. |

Walk / cycle more / longer. Exercise / swim more. Yoga / Pilates. Gardening. Jogging. More cycling. Move all limbs when have the opportunity. Don’t skip Pilates despite how busy. Walk to shops instead of driving (like I did today). Gardening. Stretching. Planning meals / big grocery shop to avoid impulse purchases. Eat proper breakfast. Less sugary foods, drinks. Less coffee. Avoid bad / junk food. Eat less treats. Eat different food options (healthy) / check diet. Control portion size/ stop eating supper. Drink more water. Limit alcohol. Mix with more people / be more social. Lose weight. Taking time out for myself/ care more for inner being. Get more sleep. Meditation. Don’t stress / worry less about the future, finances. More reading. Physiotherapy. Regular health checks. Move to a cleaner healthier environment. More sun, more fresh air, go outside more. Less time on computer / watching TV. Camping. |

Note: For brevity (i) matters nominated multiple times are listed once only, and (ii) similar entries are grouped as one topic.

In addition the card entries include various other matters (extracted and summarised in Table 2). These give a sense of the broader range of matters individuals themselves see as important for their health. Most relate to personal issues and behaviours, and to private personal space, particularly the home. Some are not spatially dependent and are thus not reliant on the design and management of the built environment.

However, there are also convergences. Some entries (eg. reading, meditation and other ‘relaxation’ activities) require spaces with an appropriate level of amenity. Subsequent discussion indicated where this was not achieved, for example inter-looking between units in density development, the general level of air pollution (grit) and noise in the locality, closeness of windows and balconies to driveway ramps and garbage areas, un-usable yard spaces due to endemic ground insects. Other entries point to potential non-built responses that could leverage overall health. For example the interest in meditation, sewing, reading and the like could be complemented by organising groups or clubs, with the co-benefit of increased social interaction and physical activity if active transport modes are used to get there; providing local subsidised space for medical services could encourage regular visitation and preventative check-ups, as well as, again, access by active transport modes.

However, there are also convergences. Some entries (eg. reading, meditation and other ‘relaxation’ activities) require spaces with an appropriate level of amenity. Subsequent discussion indicated where this was not achieved, for example inter-looking between units in density development, the general level of air pollution (grit) and noise in the locality, closeness of windows and balconies to driveway ramps and garbage areas, un-usable yard spaces due to endemic ground insects. Other entries point to potential non-built responses that could leverage overall health. For example the interest in meditation, sewing, reading and the like could be complemented by organising groups or clubs, with the co-benefit of increased social interaction and physical activity if active transport modes are used to get there; providing local subsidised space for medical services could encourage regular visitation and preventative check-ups, as well as, again, access by active transport modes.

Table 2: Additional matters identified by participants as important to their health.

Read. Do crossword puzzles. Sew, knit, crochet, quilt. Visit doctor regularly for check-ups. Keep up medications. Get more sleep. |

Meditate. Relax more. Do not stress. Care for inner being. Go camping. Personal time to oneself |

Worry less about the future. Leisure activities with family. Keep house tidy. Less time on the computer and/or watching TV. |

Work. Spend time with loved ones/ children/ grandchildren. Less worry about finances. Physiotherapy. |

Note: A number of responses were cited by more than one participant.

The depth and range of understanding, thinking and action in the responses suggest the participants are themselves taking a broad approach to ‘health’. This is in effect an interest in their overall ‘wellbeing’, both physical and mental - though without necessarily themselves making any distinction between these two categories. And quite different to the ‘silo’ and linear, rather than networked, approaches taken all-too-often by practitioners (and researchers) in both the health and built environment fields.(18)

This finding also suggest a positive lesson for built environment/urban planning ‘interventions’: that specific design, construction and management actions can generate not just singular benefits, but potentially a whole series of co-benefits (‘synergies’) – for both the benefit of the population itself and efficiencies in resource allocation and use.

Overall, it was found that participants invariably ‘got it’ in terms of what they needed to do to maintain and improve their health and wellbeing. Further, this included, as well illustrated in the following participant comment, an understanding of a necessary convergence of personal responsibility to engage in health-supportive behaviour and community responsibility to provide environments that facilitate, and not hinder, such behaviour.

"So the questions you’re asking, what I do to keep healthy? That’s us. We need to do that. What should I do to keep healthy? That’s [also up to] us. What is helping me to keep healthy? This is about our community. What could actually help us? By having better gyms, all this sort of stuff… What I need to [do]. … that’s what I see the linkage coming through … That’s really - we’ve got to do that and make the choices, and we don’t. You can see [from the cards], we don’t. I go to [the liquor store]. I [shouldn’t], I know that."(19)

A full summary of the workshop and other study findings is available here.

Implications

The research generated 14 conclusions about necessary health-supportive actions for inclusion in urban design, development and management processes (20); 11 are relevant to mental health:

This final point also suggests a critical and much-needed follow-up question: just why is it that we seem to lack these necessary levels of engagement in our city building processes, ultimately to the detriment of the wellbeing of us all as city residents, users, and practitioners?

This finding also suggest a positive lesson for built environment/urban planning ‘interventions’: that specific design, construction and management actions can generate not just singular benefits, but potentially a whole series of co-benefits (‘synergies’) – for both the benefit of the population itself and efficiencies in resource allocation and use.

Overall, it was found that participants invariably ‘got it’ in terms of what they needed to do to maintain and improve their health and wellbeing. Further, this included, as well illustrated in the following participant comment, an understanding of a necessary convergence of personal responsibility to engage in health-supportive behaviour and community responsibility to provide environments that facilitate, and not hinder, such behaviour.

"So the questions you’re asking, what I do to keep healthy? That’s us. We need to do that. What should I do to keep healthy? That’s [also up to] us. What is helping me to keep healthy? This is about our community. What could actually help us? By having better gyms, all this sort of stuff… What I need to [do]. … that’s what I see the linkage coming through … That’s really - we’ve got to do that and make the choices, and we don’t. You can see [from the cards], we don’t. I go to [the liquor store]. I [shouldn’t], I know that."(19)

A full summary of the workshop and other study findings is available here.

Implications

The research generated 14 conclusions about necessary health-supportive actions for inclusion in urban design, development and management processes (20); 11 are relevant to mental health:

- When developing new neighbourhoods, create links and networks to existing facilities in the surrounding locality to reduce capital costs, increase the viability of those existing facilities, generate added opportunities for social interaction, and promote access by ‘active’ walking and cycling.

- Ongoing management is as important as initial provision - facilities will not be used if poorly maintained, do not have convenient opening hours, do not adequately manage behaviour of users, are not affordable, or lack child care.

- Active recreation facilities need to cater for both personal/group and formal/informal activities – participants expressed a desire for spaces for informal ball sports, level running and exercise surfaces, fixed exercise stations, as well as organised activity to encourage participation.

- There was a substantial interest in ‘active’ walking, and potentially also in cycling, for recreation and active transport – this can be capitalised on by the provision of infrastructure, including a variety of routes and destinations.

- There is still a ‘default’ to a sedentary and socially-isolating car culture – addressing this requires not just adequate infrastructure for alternative transport modes but also specific programs to shift established habits and perceptions.

- There needs to be early provision of walkable local centres to instill initial health-supportive behaviours - this may require imaginative solutions, such as ‘pop-up’ facilities, temporary subsidies, and specific management interventions.

- Actions need to be place-specific (one size does not fit all) - requiring good on-ground assessments of need and liaison with/‘listening to’ local populations.

- Residents often do not know what is available to support their desires for good levels of overall wellbeing – there needs to be effective sources of local information.

- A high proportion of deficiencies in otherwise health-supportive infrastructure were due to poor detailing – there is a need for a greater ‘pains-taking’ attention to the intricacies of detail and the small scale.

- Health-supportive actions need to be flexible and open to co-opting contemporary trends and ‘fashions’ as they come (and possibly go) – eg. the café society, ‘pop-ups’, pet-friendly parks and other facilities, food trucks, men’s sheds, community gardens, group exercise classes and personal trainers.

- Finally, although most of these observations appear to be inherently logical and not overly difficult to implement, they are for some reason too-often not carried through – this study has also concluded that there is a need for a more empathic engagement by designers and managers to their task, where they ‘put themselves in the shoes’ of residents to ensure environments that accurately meet health needs and ensure up-take are actually achieved.

This final point also suggests a critical and much-needed follow-up question: just why is it that we seem to lack these necessary levels of engagement in our city building processes, ultimately to the detriment of the wellbeing of us all as city residents, users, and practitioners?

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS

References

(1) Refer: https://cityfutures.be.unsw.edu.au/research/projects/planning-and-building-healthy-communities-a-multidisciplinary-study-of-the-relationship-between-the-built-environment-and-human-health/

(2) Kent J, Thompson S. & Jalaludin B. (2011). Healthy Built Environments: A Review of the Literature. Healthy Built Environments Program, City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Australia; Kent, J.L. & Thompson, S.M. 2014, ‘The Three Domains of Urban Planning for Health and Well-Being’, Journal of Planning Literature, 29(3): 239-256.

(3) Paine, G. & Thompson, S. (2016). Healthy Built Environment Indicators. City Wellbeing Program, City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales Australia

(4) Alexander, C. (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

(5) Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., Jacobson, M., Fiksdahl-King, I., & Angel, S. (1977). A pattern language. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p.1168; Grabow, S. (1983). Christopher Alexander. The Search for a New Paradigm in Architecture. Abington, England: Routledge Kegan & Paul; Quillien, J. (2014): A History from A Pattern Language to the Nature of Order. Video presentation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ad5XAPgKJoM.

(6) Chermayeff, S., & Alexander, C. (1963). Community and privacy: Toward a new architecture of humanism. New York, NY: Doubleday. p.109.

(7) Alexander, C. (1979). The timeless way of building. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p.48.

(8) Alexander, C. (2001). The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe (Book 1: The Phenomenon of Life). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p.382.

(9) Alexander, C. (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p.120.

(10) Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., Jacobson, M., Fiksdahl-King, I., & Angel, S. (1977). A pattern language. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

(11) Schuler, D. (2009). Choosing Success: Pattern Languages as Critical Enablers of Civic Intelligence in Neis, H. & Brown, G. (Eds.): Challenges for Patterns, Pattern Languages and Sustainbility. PUARL Press, 2009. pp. 132-142.

(12) Paine, G. (2015). A pattern-generating tool for use in semi-structured interviews. The Qualitative Report, 20(4), 471-484. Retrieved from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR20/4/paineHT2.pdf

(13) McKnight, J. (1991). Looking at capacity, not deficiency. Washington, DC: National Centre for Neighborhood Enterprises.

(14) Williams, M. (2002). Interview on the health report. ABC Radio National. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/healthreport/buddhist-style-meditation-to-prevent-the/3510766

(15) Chermayeff, S., & Alexander, C. (1963). Community and privacy: Toward a new architecture of humanism. New York, NY: Doubleday. p.159; Alexander, C. (1964) Notes on a Synthesis of Form. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

(16) Workshop participant, Victoria Park 25 August 2014.

(17) City Futures Research Centre (2016). Planning and Building Healthy Communities-Summation Report: What contributes to a built environment that supports our health? University of New South Wales, Australia.

(18) Kent, J.L. & Thompson, S.M. (2012). Health and the Built Environment: Exploring Foundations for a New Interdisciplinary Profession. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, Article ID 958175: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/jeph/2012/958175/

(19) Workshop participant, Victoria Park 25 August 2014.

(20) City Futures Research Centre (2016). Planning and Building Healthy Communities-Summation Report: What contributes to a built environment that supports our health? University of New South Wales, Australia.

Acknowledgements

The Planning and Building Healthy Communities study was funded by an Australian Research Council Grant and conducted with partners UrbanGrowth NSW, the Heart Foundation (NSW) and the South Western Sydney Local Health District (NSW Health). It received ethics approvals from the Faculty of the Built Environment, University of New South Wales Australia. Future papers on the methodology and outcomes are proposed for relevant built environment and health practice journals.

Acknowledgement and appreciation is expressed to the residents of each study area who participated in the research by way of interview and/or a workshop.

Acknowledgement and appreciation is also expressed to Sara Ishikawa, Michael Mehaffy, Jenny Quillien and Friedner Wittman, all of whom have worked with Christopher Alexander, for their advices regarding the involvement of the National Institute for Mental Health in the early work of Alexander.

(1) Refer: https://cityfutures.be.unsw.edu.au/research/projects/planning-and-building-healthy-communities-a-multidisciplinary-study-of-the-relationship-between-the-built-environment-and-human-health/

(2) Kent J, Thompson S. & Jalaludin B. (2011). Healthy Built Environments: A Review of the Literature. Healthy Built Environments Program, City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Australia; Kent, J.L. & Thompson, S.M. 2014, ‘The Three Domains of Urban Planning for Health and Well-Being’, Journal of Planning Literature, 29(3): 239-256.

(3) Paine, G. & Thompson, S. (2016). Healthy Built Environment Indicators. City Wellbeing Program, City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales Australia

(4) Alexander, C. (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

(5) Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., Jacobson, M., Fiksdahl-King, I., & Angel, S. (1977). A pattern language. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p.1168; Grabow, S. (1983). Christopher Alexander. The Search for a New Paradigm in Architecture. Abington, England: Routledge Kegan & Paul; Quillien, J. (2014): A History from A Pattern Language to the Nature of Order. Video presentation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ad5XAPgKJoM.

(6) Chermayeff, S., & Alexander, C. (1963). Community and privacy: Toward a new architecture of humanism. New York, NY: Doubleday. p.109.

(7) Alexander, C. (1979). The timeless way of building. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p.48.

(8) Alexander, C. (2001). The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe (Book 1: The Phenomenon of Life). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p.382.

(9) Alexander, C. (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p.120.

(10) Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., Jacobson, M., Fiksdahl-King, I., & Angel, S. (1977). A pattern language. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

(11) Schuler, D. (2009). Choosing Success: Pattern Languages as Critical Enablers of Civic Intelligence in Neis, H. & Brown, G. (Eds.): Challenges for Patterns, Pattern Languages and Sustainbility. PUARL Press, 2009. pp. 132-142.

(12) Paine, G. (2015). A pattern-generating tool for use in semi-structured interviews. The Qualitative Report, 20(4), 471-484. Retrieved from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR20/4/paineHT2.pdf

(13) McKnight, J. (1991). Looking at capacity, not deficiency. Washington, DC: National Centre for Neighborhood Enterprises.

(14) Williams, M. (2002). Interview on the health report. ABC Radio National. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/healthreport/buddhist-style-meditation-to-prevent-the/3510766

(15) Chermayeff, S., & Alexander, C. (1963). Community and privacy: Toward a new architecture of humanism. New York, NY: Doubleday. p.159; Alexander, C. (1964) Notes on a Synthesis of Form. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

(16) Workshop participant, Victoria Park 25 August 2014.

(17) City Futures Research Centre (2016). Planning and Building Healthy Communities-Summation Report: What contributes to a built environment that supports our health? University of New South Wales, Australia.

(18) Kent, J.L. & Thompson, S.M. (2012). Health and the Built Environment: Exploring Foundations for a New Interdisciplinary Profession. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, Article ID 958175: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/jeph/2012/958175/

(19) Workshop participant, Victoria Park 25 August 2014.

(20) City Futures Research Centre (2016). Planning and Building Healthy Communities-Summation Report: What contributes to a built environment that supports our health? University of New South Wales, Australia.

Acknowledgements

The Planning and Building Healthy Communities study was funded by an Australian Research Council Grant and conducted with partners UrbanGrowth NSW, the Heart Foundation (NSW) and the South Western Sydney Local Health District (NSW Health). It received ethics approvals from the Faculty of the Built Environment, University of New South Wales Australia. Future papers on the methodology and outcomes are proposed for relevant built environment and health practice journals.

Acknowledgement and appreciation is expressed to the residents of each study area who participated in the research by way of interview and/or a workshop.

Acknowledgement and appreciation is also expressed to Sara Ishikawa, Michael Mehaffy, Jenny Quillien and Friedner Wittman, all of whom have worked with Christopher Alexander, for their advices regarding the involvement of the National Institute for Mental Health in the early work of Alexander.

About the Authors

|

Greg Paine PhD is an environmental planner with extensive experience in government. He is currently engaged as a researcher within the City Wellbeing Program, University of New South Wales Australia looking at the intersection of urban planning and health. His personal interest in pattern is being developed into a book and a forthcoming website.

|

|

Susan Thompson PhD is Professor of Planning and Head of the City Wellbeing Program in the City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales Australia. Susan’s academic career encompasses research and teaching in a range of areas, from social and cultural diversity in urban planning, to migrant women’s meanings of home, and the use of qualitative research in built environment disciplines. Susan’s current focus is on the interdisciplinary area of healthy urban planning, including advancing understandings about the supportive nature of the built environment for health and wellbeing as part of everyday living, and contributing to legislative innovation and professional practice. Her longstanding contribution to urban planning was recognised in 2015 with the award of the prestigious Sidney Luker Memorial Medal.

|

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS