|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:10

|

RESEARCH

MoMe@school – A pilot study on a analytical and participatory tool for active learning spaces design

Marianne Halblaub Miranda(1), Maria Ustinova(2), Thomas Tregel(1), Martin Knöll(1)

(1) Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany

(2) World Bank, Russia Country Office, Moscow, Russia

(1) Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany

(2) World Bank, Russia Country Office, Moscow, Russia

Key messages for urban planning and design

This article points to the importance of participatory approaches in designing physical and mental health into learning environments. Urban designers should aim to interconnect micro and macro scales of health-oriented planning, consider the importance of small restorative niches for young students, and explore new digital tools to co create learning environments. The researchers suggest that the MoMe@school instrument could be used in child-led assessments in all areas where children are active users of the space: both indoors and outdoors, including public spaces in residential housing, playgrounds, hospitals, schools, kindergartens, probably shopping and entertainment areas, parks, and even perhaps for transport infrastructure.

This article points to the importance of participatory approaches in designing physical and mental health into learning environments. Urban designers should aim to interconnect micro and macro scales of health-oriented planning, consider the importance of small restorative niches for young students, and explore new digital tools to co create learning environments. The researchers suggest that the MoMe@school instrument could be used in child-led assessments in all areas where children are active users of the space: both indoors and outdoors, including public spaces in residential housing, playgrounds, hospitals, schools, kindergartens, probably shopping and entertainment areas, parks, and even perhaps for transport infrastructure.

Background

Current studies underline the influence of designed spaces on the learning progress and the social interaction of young students. In pedagogy, the physical environment is already understood as a “third teacher”: a spatial framework for learning processes that can independently facilitate the development of children (Mau et al., 2010). Recent studies show, that high quality design of the classrooms can explain a 16% improvement in learning over a year (Barret et al., 2015). Learning and teaching digital skills adds new requirements to the organization of learning environments, as well as to the competences of the children (Driskell, 2002). However, the empirical research on the specific role of design with respect to children’s learning achievements, health and health-related behavior remains very fragmented and unexplored (Montag, 2013).

The school is regarded as an important setting (field of action) to foster activity and healthy behaviors including active transport such as walking or cycling to and from the school facilities (Audrey et al., 2015). The World Health Organization (WHO, 1995) defines a health-promoting school as an institution that creates an healthy environment, provides the programs and services to support physical and mental health of the staff, children, their families and community members. There are numerous international initiatives dedicated to health promotion in schools, but as the evidence shows, the most effective are the multi-layered programs on supporting mental health, nutrition and physical activity. In Germany, the Hessen Ministry of Culture offers schools the opportunity to obtain "health promoting schools" certification within the framework of the initiative "School & Health" (Hessisches Kultusministerium, 2012). The certification is divided into the following aspects:

The procedure of obtaining this certificate includes a series of self-evaluation and external evaluation sessions, which help the school team to review and incorporate healthy behavior and education in everyday activities. However, the evaluation criteria do not reflect the spatial component (other than working space for teachers) and thus, does not assist in analyzing and understanding the school’s built environment and the behavior of the users in it. Consulting its users and observing their activities and interactions is not part of the procedure.

At the same time there is a growing body of research that emphasizes how design strategies need to connect micro scale (e.g. the classroom, school facilities and open space) to macro scale (streetscape, neighborhood, mobility systems) planning in order to support formal and informal learning activities and active travel (Deinet, 2015). This line of investigation points to positive effects on children’s overall physical activity, attention span and stress coping, cognitive ability as well as informal learning while roaming out and about. We argue that the interconnection between urban design and school architecture works in both directions:

We argue that enabling students to participate in research and design processes is key to developing more active learning environments.

Meanwhile, there is a growing demand for new construction and upgrading of school buildings in Germany with an existing stock of facilities mainly built in the period between 1960-1980s (Klima et al., 2006; Montag Stiftung, 2013). The experts highlight the importance of so-called “zero” phase of the design planning process: creation of high quality briefs for the school design which must incorporate the pedagogical concept and the needs and demands of the school users and local community in order to ensure the relevance and usability of the future school building. This presents itself as an opportunity to open a discussion about students’ perception of the built environment and bring forward what their expectations and needs are regarding health-promoting schools.

The empirical data, identification, and analysis of health-promoting structures and an explicit understanding of individual behavior can be helpful for the development of health-promoting spaces. For young people and children, participating in projects in which they can design spaces has several positive effects on learning, identification, better catering and acceptance of their needs, and better wellbeing. At the same time, it is widely accepted that the projects benefit from young peoples’ expertise in local knowledge and their age-specific needs (Driskell, 2002). Participation is seen as a key aspect of the successful design of health-promoting urban environments (Knöll, 2012). It is surprising that both – a broader base on empiric data on students perception as well as their participation in the process - plays such a little role in the field of health and school design. To achieve that, the planners need new tools to evaluate the school environment, as well as to involve the school users, both students and teachers, into joint investigation to collect and analyze their needs. Such analysis shall consider parameters of school design (geometric shape, topology and surface qualities, furnishing, etc.) and spatial perception parameters of both students and teachers (suitability of the premises for the various school activities: learning, relaxing, being physically active, social interaction, etc.). The results of the analysis may complement the ‘health-promoting’ certification process and bring additional inputs for future debates on how the built environment influences health-related activities.

Approach

The overall aim of the research project is to understand better the influence of the built environment on learning, physical activity and the wellbeing of students. This entails identifying discrete architectural elements and configurations, which encourage certain behaviors. In a first step, a series of interactions and data gathering methods to gain a broader and more detailed empirical basis about students’ perception and use of the learning spaces were collected. From this, researchers conceived and developed a prototype toolbox, which consists of information about health-promoting design for teachers and students, material for interviews, and a playful mobile application.

The pilot project started in November 2016 in an elementary school in Darmstadt, Germany. In preliminary discussions with the school administration, spatial categories were agreed upon, catering specific open questions for the school building (Table 1).

Current studies underline the influence of designed spaces on the learning progress and the social interaction of young students. In pedagogy, the physical environment is already understood as a “third teacher”: a spatial framework for learning processes that can independently facilitate the development of children (Mau et al., 2010). Recent studies show, that high quality design of the classrooms can explain a 16% improvement in learning over a year (Barret et al., 2015). Learning and teaching digital skills adds new requirements to the organization of learning environments, as well as to the competences of the children (Driskell, 2002). However, the empirical research on the specific role of design with respect to children’s learning achievements, health and health-related behavior remains very fragmented and unexplored (Montag, 2013).

The school is regarded as an important setting (field of action) to foster activity and healthy behaviors including active transport such as walking or cycling to and from the school facilities (Audrey et al., 2015). The World Health Organization (WHO, 1995) defines a health-promoting school as an institution that creates an healthy environment, provides the programs and services to support physical and mental health of the staff, children, their families and community members. There are numerous international initiatives dedicated to health promotion in schools, but as the evidence shows, the most effective are the multi-layered programs on supporting mental health, nutrition and physical activity. In Germany, the Hessen Ministry of Culture offers schools the opportunity to obtain "health promoting schools" certification within the framework of the initiative "School & Health" (Hessisches Kultusministerium, 2012). The certification is divided into the following aspects:

- Food & consumer education,

- Movement and perception,

- Traffic education/mobility training,

- Prevention of drug addiction and violence,

- Health of teachers.

The procedure of obtaining this certificate includes a series of self-evaluation and external evaluation sessions, which help the school team to review and incorporate healthy behavior and education in everyday activities. However, the evaluation criteria do not reflect the spatial component (other than working space for teachers) and thus, does not assist in analyzing and understanding the school’s built environment and the behavior of the users in it. Consulting its users and observing their activities and interactions is not part of the procedure.

At the same time there is a growing body of research that emphasizes how design strategies need to connect micro scale (e.g. the classroom, school facilities and open space) to macro scale (streetscape, neighborhood, mobility systems) planning in order to support formal and informal learning activities and active travel (Deinet, 2015). This line of investigation points to positive effects on children’s overall physical activity, attention span and stress coping, cognitive ability as well as informal learning while roaming out and about. We argue that the interconnection between urban design and school architecture works in both directions:

- Health promoting urban design (e.g. walkability, green and blue infrastructure, access to different modes of transportation) can support active transportation as part of multifaceted mobility educational programs such as “Safe Road to School”.

- Urban design, especially the ideas of placemaking and co-design, can assist creating school facilities and open spaces that are more active and safe. For example, Jane Jacobs’ (1961) classic idea of all "eyes on the street" helps to prevent bullying in communal spaces, while Whyte’s (1980) triangulation in public space design can help to create communal spaces that support social interaction and co learning.

We argue that enabling students to participate in research and design processes is key to developing more active learning environments.

Meanwhile, there is a growing demand for new construction and upgrading of school buildings in Germany with an existing stock of facilities mainly built in the period between 1960-1980s (Klima et al., 2006; Montag Stiftung, 2013). The experts highlight the importance of so-called “zero” phase of the design planning process: creation of high quality briefs for the school design which must incorporate the pedagogical concept and the needs and demands of the school users and local community in order to ensure the relevance and usability of the future school building. This presents itself as an opportunity to open a discussion about students’ perception of the built environment and bring forward what their expectations and needs are regarding health-promoting schools.

The empirical data, identification, and analysis of health-promoting structures and an explicit understanding of individual behavior can be helpful for the development of health-promoting spaces. For young people and children, participating in projects in which they can design spaces has several positive effects on learning, identification, better catering and acceptance of their needs, and better wellbeing. At the same time, it is widely accepted that the projects benefit from young peoples’ expertise in local knowledge and their age-specific needs (Driskell, 2002). Participation is seen as a key aspect of the successful design of health-promoting urban environments (Knöll, 2012). It is surprising that both – a broader base on empiric data on students perception as well as their participation in the process - plays such a little role in the field of health and school design. To achieve that, the planners need new tools to evaluate the school environment, as well as to involve the school users, both students and teachers, into joint investigation to collect and analyze their needs. Such analysis shall consider parameters of school design (geometric shape, topology and surface qualities, furnishing, etc.) and spatial perception parameters of both students and teachers (suitability of the premises for the various school activities: learning, relaxing, being physically active, social interaction, etc.). The results of the analysis may complement the ‘health-promoting’ certification process and bring additional inputs for future debates on how the built environment influences health-related activities.

Approach

The overall aim of the research project is to understand better the influence of the built environment on learning, physical activity and the wellbeing of students. This entails identifying discrete architectural elements and configurations, which encourage certain behaviors. In a first step, a series of interactions and data gathering methods to gain a broader and more detailed empirical basis about students’ perception and use of the learning spaces were collected. From this, researchers conceived and developed a prototype toolbox, which consists of information about health-promoting design for teachers and students, material for interviews, and a playful mobile application.

The pilot project started in November 2016 in an elementary school in Darmstadt, Germany. In preliminary discussions with the school administration, spatial categories were agreed upon, catering specific open questions for the school building (Table 1).

Table 1: Spatial categories translated to English with an explanation text, which was also shown on screen.

Category |

Explanation text |

Relaxing |

I feel relaxed here. I can recover and rest without worries. |

Suitable for physical activity |

I can move around and be active here. |

My favorite place |

I like it very much here, I can do a lot here and I always feel comfortable doing it. |

Good place to study/learn |

I can always study well and comfortably here. |

A place I dislike |

I don’t feel comfortable or at ease here. |

The chosen categories are derived to deliver insights about wellbeing in a learning context at different levels. In order to understand which areas could play an important role in supporting mental health by allowing children to enjoy themselves and feel carefree, the categories “relaxing” and “favorite” were asked separately. Ideally, places that support mental health are easily accessible and are part of their daily routine. On the other hand, the last category, “a place I dislike” is of absolute importance in a mental health context because of its possible negative influence; finding out whether the places being mentioned are places that children have to use often in their daily routine points out to what to prioritize when planning constructional redevelopments.

The category “suitable for physical activity” should deliver the spaces where children feel free to move and acknowledge them as areas to be active. This is crucial in learning environments, since several studies have pointed out the link between physical activity and cognitive function, which supports academic performance (Carlson et al., 2008; Fedewa & Ahn., 2011; Howie et al., 2012). The fourth category, “a good place to study”, should help researchers to identify the spatial setup and the most important elements that allow this space to be created and if they have any connection, similarities or differences to the before mentioned categories.

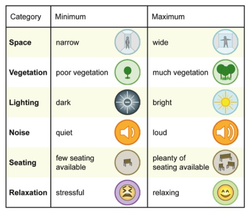

After choosing a space, students rated it according to six core aspects of environmental and behavioral experience, first presented in by Knöll et al. (2015) and adapted to school environments. Here, instead of asking them to give the variables a value in a ten-step semantic differential scale, children were invited to choose between opposite adjectives represented by icons in the form of stickers, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

The category “suitable for physical activity” should deliver the spaces where children feel free to move and acknowledge them as areas to be active. This is crucial in learning environments, since several studies have pointed out the link between physical activity and cognitive function, which supports academic performance (Carlson et al., 2008; Fedewa & Ahn., 2011; Howie et al., 2012). The fourth category, “a good place to study”, should help researchers to identify the spatial setup and the most important elements that allow this space to be created and if they have any connection, similarities or differences to the before mentioned categories.

After choosing a space, students rated it according to six core aspects of environmental and behavioral experience, first presented in by Knöll et al. (2015) and adapted to school environments. Here, instead of asking them to give the variables a value in a ten-step semantic differential scale, children were invited to choose between opposite adjectives represented by icons in the form of stickers, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: Screenshot of the mobile application. Translation: “How would you describe this space?”

Figure 2: The six polar adjectives translated to English describing environmental and behavioral experiences and their representation as stickers

The pilot study – the first group

The total number of participants in the pilot study was 75 students, comprising first to fourth graders aged 6-10 years. The first test of the pilot project took place in February 2017 with a group of third and fourth graders (n=28). From this first group, the authors report on the tests of the mobile application, followed by interviews about the interaction and the digital tool and a creative workshop for participants to express their needs and wishes for certain spaces.

The context-sensitive mobile application, MoMe@school, encourages students to explore their school, both indoors and outdoors, and deliver insights about how they perceive their school. The children’s game “I spy with my little eye” served as inspiration for the game that was developed using the Unity Engine and adapted to a mobile interface. For the data collection, each student receives a smartphone. After logging in, preferably with a nickname, students must walk around their school, look for different type of spaces (spatial categories shown in Table 1), shoot photographs, and describe them with a set of adjectives represented by stickers (Figures 1 and 2). Meanwhile, the application records the students’ navigation – GPS tracks – and perception through photographs and ratings of the space. Concluding the interaction, an interview is done. To collect information about the experience of the students from the third and fourth grade related to the mobile application usage and their perception of this activity, a set of open questions was developed. These questions covered the personal experience about school spaces analyzed during the test, as well as the opinion about the relevance and design of the mobile application. Having completed the test run with MoMe@school, each participant joined in a conversation with the team expert and shared his or her answers.

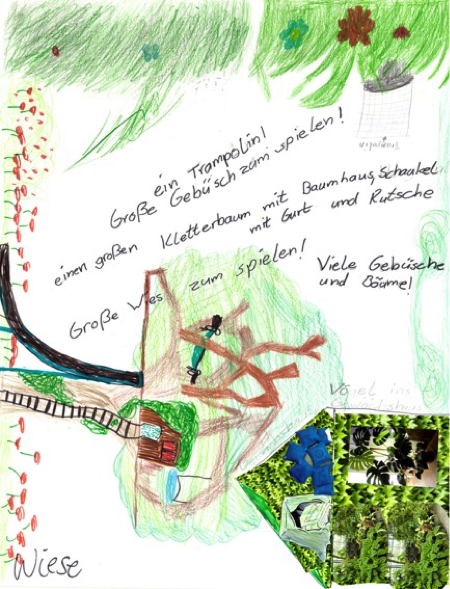

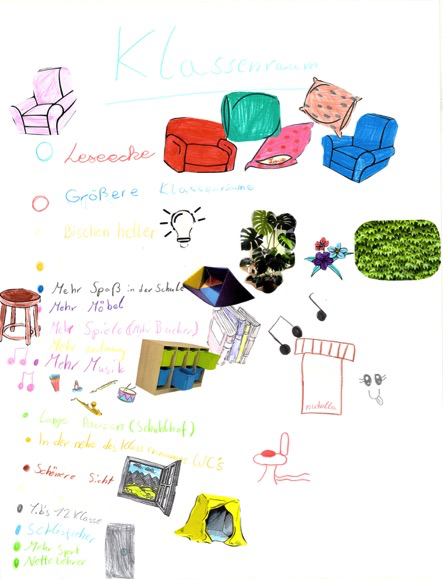

In June 2017 the children were asked to reflect on how they use the space in their school and around it (neighborhood level), what new aspects they might have learned about their school, and were encouraged to share their ideas to improve some spaces and visions of how to make the most of spaces that have, in their eyes, potential. For this, they chose 4 different spaces that were often photographed in February (Figure 3) and did mood boards, drawings and collages (Figure 4).

Preliminary results

During the activity, several students noticed either places which they had not used regularly before (e.g. the jungle gym in the yard) or some elements (e.g. the trees in the schoolyard) to which they had not previously paid attention. Additionally, they identified and located some spaces, rooms, and areas, which were locked or could not be reached without adult’s supervision, which were considered by the children to be relevant, interesting or positive for their school life.

In the subsequent interviews to the interaction with the app, all students rated the game as an enjoyable and positive experience which took place in the middle of their daily school routine. They were surprised that they were allowed to use the smartphones in school and some of them mentioned that it was the first time this type of IT gadget was used for any school activity.

Participants also highlighted that they enjoyed having the opportunity to express their opinion about their school. At the same time, one child noted the importance of anonymity in providing their views, especially about places with poor or bad qualities in the school.

All children confirmed that the different icons, which reflected the meaning of semantic differential scale, were useful and correctly designed. Additionally, the children suggested new combinations for expanding the set of semantic differential scale including “colorful/colorless”; “happy/sad”; “alone/together with friends”; “in movement/calmness”; “beautiful/disgusting”; “nice/annoying”. The majority of the children rated the icons with a human face (smile) higher than the other images. The students proposed the introduction of more categories related to human emotions.

Some children asked how to use the application during the activity and they claimed to experience difficulties while switching between different spatial categories. Nevertheless, all of them completed the task of evaluating the 5 different spatial categories (n=28), with the majority taking several pictures for each category (Figure 3).

The total number of participants in the pilot study was 75 students, comprising first to fourth graders aged 6-10 years. The first test of the pilot project took place in February 2017 with a group of third and fourth graders (n=28). From this first group, the authors report on the tests of the mobile application, followed by interviews about the interaction and the digital tool and a creative workshop for participants to express their needs and wishes for certain spaces.

The context-sensitive mobile application, MoMe@school, encourages students to explore their school, both indoors and outdoors, and deliver insights about how they perceive their school. The children’s game “I spy with my little eye” served as inspiration for the game that was developed using the Unity Engine and adapted to a mobile interface. For the data collection, each student receives a smartphone. After logging in, preferably with a nickname, students must walk around their school, look for different type of spaces (spatial categories shown in Table 1), shoot photographs, and describe them with a set of adjectives represented by stickers (Figures 1 and 2). Meanwhile, the application records the students’ navigation – GPS tracks – and perception through photographs and ratings of the space. Concluding the interaction, an interview is done. To collect information about the experience of the students from the third and fourth grade related to the mobile application usage and their perception of this activity, a set of open questions was developed. These questions covered the personal experience about school spaces analyzed during the test, as well as the opinion about the relevance and design of the mobile application. Having completed the test run with MoMe@school, each participant joined in a conversation with the team expert and shared his or her answers.

In June 2017 the children were asked to reflect on how they use the space in their school and around it (neighborhood level), what new aspects they might have learned about their school, and were encouraged to share their ideas to improve some spaces and visions of how to make the most of spaces that have, in their eyes, potential. For this, they chose 4 different spaces that were often photographed in February (Figure 3) and did mood boards, drawings and collages (Figure 4).

Preliminary results

During the activity, several students noticed either places which they had not used regularly before (e.g. the jungle gym in the yard) or some elements (e.g. the trees in the schoolyard) to which they had not previously paid attention. Additionally, they identified and located some spaces, rooms, and areas, which were locked or could not be reached without adult’s supervision, which were considered by the children to be relevant, interesting or positive for their school life.

In the subsequent interviews to the interaction with the app, all students rated the game as an enjoyable and positive experience which took place in the middle of their daily school routine. They were surprised that they were allowed to use the smartphones in school and some of them mentioned that it was the first time this type of IT gadget was used for any school activity.

Participants also highlighted that they enjoyed having the opportunity to express their opinion about their school. At the same time, one child noted the importance of anonymity in providing their views, especially about places with poor or bad qualities in the school.

All children confirmed that the different icons, which reflected the meaning of semantic differential scale, were useful and correctly designed. Additionally, the children suggested new combinations for expanding the set of semantic differential scale including “colorful/colorless”; “happy/sad”; “alone/together with friends”; “in movement/calmness”; “beautiful/disgusting”; “nice/annoying”. The majority of the children rated the icons with a human face (smile) higher than the other images. The students proposed the introduction of more categories related to human emotions.

Some children asked how to use the application during the activity and they claimed to experience difficulties while switching between different spatial categories. Nevertheless, all of them completed the task of evaluating the 5 different spatial categories (n=28), with the majority taking several pictures for each category (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Participants using the application around the schoolyard

In the second step of data analysis, researchers identified the different areas that were photographed for each category. The majority of participants (both girls and boys) photographed the toilets as the place they most dislike (n=15). Many photographed a reading corner inside their classrooms as the most relaxing spot (n=8). Here, children can sit on sofas, which they stated was a nice change to the hours spent sitting on normal school chairs. Only 3 out of 8 classrooms had such a corner, which was also often photographed as the best place to learn (n=4); the classroom itself led in this category.

The gymnasium was stated as one of the best-suited places for physical activity (n=7), only topped by the jungle gym (n=10). The latter was as well mentioned as the top favorite place (n=4) followed by the Ping-Pong table (n=4).

The third step was the hands-on workshop, where researchers learned what students envision and wish to change in the spaces they are allowed to use as well as some spaces that they would like to use. Figure 4 shows two such examples: first, a green outdoor space to relax in, with a group of students in a green meadow they are normally not allowed to access; second, a list of requirements for a comfortable and appealing classroom.

The gymnasium was stated as one of the best-suited places for physical activity (n=7), only topped by the jungle gym (n=10). The latter was as well mentioned as the top favorite place (n=4) followed by the Ping-Pong table (n=4).

The third step was the hands-on workshop, where researchers learned what students envision and wish to change in the spaces they are allowed to use as well as some spaces that they would like to use. Figure 4 shows two such examples: first, a green outdoor space to relax in, with a group of students in a green meadow they are normally not allowed to access; second, a list of requirements for a comfortable and appealing classroom.

Figure 4: Participants' collages describing their vision of what they would like to change or use.

1: Collage showing a tree house, a greenhouse and some statements requiring more contact with vegetation.

2: List of things needed for a great classroom, including: a reading corner with comfortable seating, more light and greenery, storage space and more material to play and learn.

1: Collage showing a tree house, a greenhouse and some statements requiring more contact with vegetation.

2: List of things needed for a great classroom, including: a reading corner with comfortable seating, more light and greenery, storage space and more material to play and learn.

Discussion

The majority of German schools have recently introduced a smartphone-ban, making the opportunity to use smartphones appealing and stimulated children to participate in the activity with great enthusiasm. Some participants said that they had never before been asked about how they see their school or to “tell a story” about it by taking pictures, making the task absorbing and reflective for them. They expressed gladness that their opinion was valued and were excited by the prospect of their ideas leading to positive changes in their school. They also expressed that being allowed to enter a nickname instead of their real name was a good measure to make them feel safe while sharing their opinions. Several students expressed difficulties in understanding certain definitions within the spatial categories, prompting the researchers to discuss in further steps the list of categories with different age/grade groups, and to adjust the definitions accordingly. On the other hand, the presented set of adjectives (Figure 2) to rate the spaces was endorsed as useful, and possible additions have been revealed from the children’s feedback.

The collected data creates a first database for the perception of different areas of the school: from particularly popular to less used. The findings suggest that engaging students in the process will contribute to a better understanding of spatial expectations, needs and requirements for school design.

Students identified the following aspects as most important and in need of action:

Students reported the following as not sufficiently available:

The use of digital technology in co-design and placemaking processes is still a relatively new field of research. Potential benefits of “urban gaming” have been identified for young people in promoting physical activity and mental wellbeing, as well as acquiring new health literacy (Knöll et al, 2014; Halblaub Miranda et al. 2016). The underlying mechanics and potential pitfalls are far from being comprehensively understood and there is only a limited amount of empiric data available. This is particularly true for the context of a primary school environment, i.e. co-design with young children between 6-10. This pilot study has shown that young students are keen to use smartphones, and this tool could be a catalyst to engage them in co-design activities. There remain open questions, for example in how far a digitally supported co-design tool box like MoMe@school may spark interest in co-design processes outside the school environment, or in how far the multitude of available smartphone sensors can be used to challenge spatial awareness or to assist students in a playful manner.

The limitation of the majority of these instruments is that observations are often undertaken by adults or questioners and rarely involve children as the active participants of the evaluation process. Some examples include School-Age Care Environment Rating Scale (SACERS)iv or Ofsted questionnaires for the inspection of schools. Ofsted is a UK agency that does quality assurance evaluations, usually these are observations and surveys, and some of their tools take into account mental health. The researchers suggest that the instrument presented in this pilot study can be used in child-led assessments in all areas where children are active users of the space: both indoors and outdoors. This includes public spaces in residential housing, playgrounds, hospitals, schools, kindergartens, probably shopping and entertainment areas, parks, and even perhaps transport infrastructure (in terms of assessing safety of the roads, public transportation stops, pedestrian crossing, etc.).

In terms of certification, child-led place assessments can become part of the quality assurance instruments both for education sector and planning/construction sector. This is being done in some countries with standardized procedures of evaluation of school or early childhood care services quality. Usually, there are two stages: self-evaluation and external evaluation. Based on the assessment results, the municipality or any other relevant authority could provide schools with support, funding or counseling services.

In the planning sector these assessments can become a part of post-occupancy evaluation (POE), where users provide their opinions about quality of the buildings, a very common part of big investment programs for updating social infrastructure. For example, POE were used in Scotland (with students’ involvement) for various school upgrading programs and recommended by local authorities as a priority tool for quality assessment.

Additionally, these child-led assessments can become a part of social impact evaluation, which are widely used to provide comprehensive analysis of various policy actions and development projects. It helps to understand the impact of design activities on various vulnerable groups of population (in our case, children). Most donors and development organizations include social impact assessment as a mandatory part of the project's appraisal cycle, and this practice is also becoming common in the real estate development sector.

Conclusions

Preliminary results include initial experiences with a new, digitally supported method for the participation of students in school design evaluation processes, and the interviews and workshops following the use of the smartphone application.

From the experiences facilitated by the MoMe@school toolbox we can conclude the following:

MoMe@school is just one mode of addressing physical and mental health in school design. It can be combined with standard self-assessment and external evaluations, which are usually done by and for pedagogical staff. The researchers appeal that designers should be granted access to the recorded data (anonymized) in order to design better spaces.

Outlook

As next steps, the researchers will use the data to outline a set of “portraits” with statements about spatial perception for each area within the school, corroborating the relevance of certain environmental and spatial parameters. The recorded qualitative data is linked to the recorded quantitative data and further quantitative spatial analysis will be undertaken. The data is currently analyzed and visualized using the MoMe@school framework in combination with Geo Information Systems (See Halblaub Miranda et al., 2015) and the Space Syntax framework (See Knöll et al., 2017).

The ongoing research aims to extend the scope of the existing research on design of healthy environments and particularly focuses on the ‘health-promoting’ schools certified by the federal state of Hesse in Germany. The main objective is to identify and analyze different aspects of the built environment, which affect children’s physical activity and mental health in school settings, building a database of school facilities in different urban settings. In a series of in situ tests, the method will be amplified by other techniques that enable students to participate in the design process of their learning spaces.

In this pilot study, the area of investigation was restricted to the school facilities. The MoMe@school tool box would in theory allow students to assess a wider area, using the smartphone app to assess the streetscape and open spaces of the school’s neighborhood or their journeys between home and school. Such an extension would require adaptions to the concept, i.e. to include staff to accompany the children, or to integrate MoMe@school to educational programs such as “Safe Road to Schools”. Active transport has been shown in many studies to contribute largely to children’s overall physical activity levels and mental wellbeing. Investigating urban design factors that hinder or promote active transport from the children’s and potentially their parents’ point of view could be very beneficial.

MoMe@school has the potential to become a useful tool for education facilities planners as it contributes to the data gathering for the “zero” phase of project planning and implementation and helps to provide rich data about user’s behavior and perceptions for the preparation of high quality design briefs. Additionally, we suggest that this type of mobile app could not only help to gather and summarize data about school environment for use in the future design process but also serve as an extracurricular learning tool aimed to improve children’s spatial orientation/navigation skills.

References

Audrey S., Batista-Ferrer H. (2015), Healthy urban environments for children and young people: A systematic review of intervention studies. Health & Place, Bd. 36, Nr. 11 (November 2015): 97-117.

Barret P., Davies F., Zhang Y., and Barret L. (2015). The impact of classroom design on pupils' learning: Final results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Building and Environment. Volume 89 (July 2015), 118–133.

Carlson, S. A., Fulton, J. E., Lee, S. M., Maynard, L. M., Brown, D. R., Harold W. Kohl, I., & Dietz, W. H. (2008). Physical Education and Academic Achievement in Elementary School: Data From the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. American Journal of Public Health, 98(4), 721-727. doi:10.2105/ajph.2007.117176

Deinet U. (2015), Raumaneignung als Bildung im Stadtraum, in: Coelen, Thomas; Heinrich Anne Juliane; Milion, Angela (eds.), Stadtbaustein Bildung, Springer, Wiesbaden, pp. 159-66.

Driskell D. (2002), Creating Better Cities with Children and Youth. Earthscan Ltd and UNESCO, London.

Fedewa, A.L., Ahn, S. (2011). The effects of physical activity and physical fitness on children’s achievement and cognitive outcomes: a meta-analysi. In Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82(3), pp. 521–535.

Halblaub Miranda, M., & Knöll, M. (January 2016). Stadtflucht - Learning about healthy places with a location-based game. (J. Ackermann, A. Rauscher, & S. Daniel, eds.) Navigationen - Zeitschrift für Medien und Kulturwissenschaften, 16, pp. 101-18.

Halblaub Miranda M., Hardy S., Knöll M. (2015). MoMe: a context-sensitive mobile application to research spatial perception and behaviour. In Proceedings of the conference on human mobility, cognition and GIS, University of Copenhagen, 29-30.

Hessisches Kultusministerium (2012). Arbeitsfeld „Schule & Gesundheit“. Hessen 2012-2016. Grundlagen – Strategien – Meilensteine. Retrieved April 3, 2017 from www.schuleundgesundheit.hessen.de

Howie, E. K., & Pate, R. R. (2012). Physical activity and academic achievement in children: A historical perspective. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 1(3), 160-169.

Jacobs J. (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Johnson L., Adams-Becker S., Estrada V, Freeman A., Kampylis P., Vuorikari R. and Yves P. (2014), Horizon Report Europe: 2014 Schools Edition. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, & Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium.

Klima M., Reiss J., Erhorn H., and Fluch M. (2006). Gebäude sanieren – Schulen. BINE Themeninfo (January 2006).

Knöll, M., Neuheuser, K., Cleff, T., & Rudolph-Cleff, A. (13. Januar 2017). A tool to predict perceived urban stress in open public spaces. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science. Online first https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813516686971

Knöll, M., & Roe, J. (31. July 2016). Pokemon Go: a tool to help urban design improve mental health? Urban Design & Mental Health: Sanity and Urbanity.

Knöll M., Li Y., Neuheuser K, Rudolph-Cleff A. (2015). Using space syntax to analyse stress ratings of open public spaces. In Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium, (SSS’10) London: University College London, 123:1-15.

Knöll, M., Dutz, T., Hardy, S., & Göbel, S. (2014). Urban Exergames – How Architects and Serious Gaming Researchers Collaborate on the Design of Digital Games that make you move. In M. Ma, L. Jain, A. Withehead, & P. Anderson (eds.), Virtual and Augmented Reality in Healthcare 1 (S. 191-207). London: Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-54816-1_11

Knöll M. (2012), Urban Health Games. Collaborative, Expressive & Reflective. Ph.D. Dissertation. Universität Stuttgart, Fakultät Architektur und Stadtplanung - Institut Grundlagen Moderner Architektur und Entwerfen, Stuttgart.

Mau B., O'Donnell, Wickl, Pigozzi and Peterson. (2010). The Third Teacher – 79 Ways You Can Use Design to Transform Teaching and Learning. Cannon Design, VS Furniture, Bruce Mau Design.

Montag Stiftung (2017). Schulen planen und bauen – Grundlagen und Prozesse; Kapitel IV, S. 135-163.

Montag Stiftung (2013). Leitlinien für leistungsfähige Schulbauten in Deutschland. 2013.

Saarloos D., Kim J.E., Timmermans H. (2009). The Built Environment and Health: Introducing Individual Space-Time Behavior. Int. J. Environ., Res. Public Health, 6(6), 1724-1743.

School health promotion: evidence for effective action. SHE Factsheet 2.

Word Health Organisation (1995). Health Promoting Schools: A Healthy Setting for Learning, Living and Working.

Whyte, W.H. (1980), The Social Life of Small Public Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces.

The majority of German schools have recently introduced a smartphone-ban, making the opportunity to use smartphones appealing and stimulated children to participate in the activity with great enthusiasm. Some participants said that they had never before been asked about how they see their school or to “tell a story” about it by taking pictures, making the task absorbing and reflective for them. They expressed gladness that their opinion was valued and were excited by the prospect of their ideas leading to positive changes in their school. They also expressed that being allowed to enter a nickname instead of their real name was a good measure to make them feel safe while sharing their opinions. Several students expressed difficulties in understanding certain definitions within the spatial categories, prompting the researchers to discuss in further steps the list of categories with different age/grade groups, and to adjust the definitions accordingly. On the other hand, the presented set of adjectives (Figure 2) to rate the spaces was endorsed as useful, and possible additions have been revealed from the children’s feedback.

The collected data creates a first database for the perception of different areas of the school: from particularly popular to less used. The findings suggest that engaging students in the process will contribute to a better understanding of spatial expectations, needs and requirements for school design.

Students identified the following aspects as most important and in need of action:

- The toilets are the are most disliked spaces (reasons were not discussed in the workshop)

- A wide range of large and small communal places in which to be physically active

Students reported the following as not sufficiently available:

- Restorative niches to relax and chat in a safe environment

- Spaces that allow a change of scenery as part of a day-long learning routine (e.g. reading corners in all classrooms and access to the meadow with some amenities)

The use of digital technology in co-design and placemaking processes is still a relatively new field of research. Potential benefits of “urban gaming” have been identified for young people in promoting physical activity and mental wellbeing, as well as acquiring new health literacy (Knöll et al, 2014; Halblaub Miranda et al. 2016). The underlying mechanics and potential pitfalls are far from being comprehensively understood and there is only a limited amount of empiric data available. This is particularly true for the context of a primary school environment, i.e. co-design with young children between 6-10. This pilot study has shown that young students are keen to use smartphones, and this tool could be a catalyst to engage them in co-design activities. There remain open questions, for example in how far a digitally supported co-design tool box like MoMe@school may spark interest in co-design processes outside the school environment, or in how far the multitude of available smartphone sensors can be used to challenge spatial awareness or to assist students in a playful manner.

The limitation of the majority of these instruments is that observations are often undertaken by adults or questioners and rarely involve children as the active participants of the evaluation process. Some examples include School-Age Care Environment Rating Scale (SACERS)iv or Ofsted questionnaires for the inspection of schools. Ofsted is a UK agency that does quality assurance evaluations, usually these are observations and surveys, and some of their tools take into account mental health. The researchers suggest that the instrument presented in this pilot study can be used in child-led assessments in all areas where children are active users of the space: both indoors and outdoors. This includes public spaces in residential housing, playgrounds, hospitals, schools, kindergartens, probably shopping and entertainment areas, parks, and even perhaps transport infrastructure (in terms of assessing safety of the roads, public transportation stops, pedestrian crossing, etc.).

In terms of certification, child-led place assessments can become part of the quality assurance instruments both for education sector and planning/construction sector. This is being done in some countries with standardized procedures of evaluation of school or early childhood care services quality. Usually, there are two stages: self-evaluation and external evaluation. Based on the assessment results, the municipality or any other relevant authority could provide schools with support, funding or counseling services.

In the planning sector these assessments can become a part of post-occupancy evaluation (POE), where users provide their opinions about quality of the buildings, a very common part of big investment programs for updating social infrastructure. For example, POE were used in Scotland (with students’ involvement) for various school upgrading programs and recommended by local authorities as a priority tool for quality assessment.

Additionally, these child-led assessments can become a part of social impact evaluation, which are widely used to provide comprehensive analysis of various policy actions and development projects. It helps to understand the impact of design activities on various vulnerable groups of population (in our case, children). Most donors and development organizations include social impact assessment as a mandatory part of the project's appraisal cycle, and this practice is also becoming common in the real estate development sector.

Conclusions

Preliminary results include initial experiences with a new, digitally supported method for the participation of students in school design evaluation processes, and the interviews and workshops following the use of the smartphone application.

From the experiences facilitated by the MoMe@school toolbox we can conclude the following:

- The digital tool could help designers and planners gather and analyze students’ opinions of their learning environment, which can serve as an aid during the planning process in construction and upgrading of education facilities by taking into account user needs.

- Children need a variety of different and flexible environments: for physical activity, relaxation, concentration, and play, which sometimes do not correspond with traditional/initially planed layout of the facility.

MoMe@school is just one mode of addressing physical and mental health in school design. It can be combined with standard self-assessment and external evaluations, which are usually done by and for pedagogical staff. The researchers appeal that designers should be granted access to the recorded data (anonymized) in order to design better spaces.

Outlook

As next steps, the researchers will use the data to outline a set of “portraits” with statements about spatial perception for each area within the school, corroborating the relevance of certain environmental and spatial parameters. The recorded qualitative data is linked to the recorded quantitative data and further quantitative spatial analysis will be undertaken. The data is currently analyzed and visualized using the MoMe@school framework in combination with Geo Information Systems (See Halblaub Miranda et al., 2015) and the Space Syntax framework (See Knöll et al., 2017).

The ongoing research aims to extend the scope of the existing research on design of healthy environments and particularly focuses on the ‘health-promoting’ schools certified by the federal state of Hesse in Germany. The main objective is to identify and analyze different aspects of the built environment, which affect children’s physical activity and mental health in school settings, building a database of school facilities in different urban settings. In a series of in situ tests, the method will be amplified by other techniques that enable students to participate in the design process of their learning spaces.

In this pilot study, the area of investigation was restricted to the school facilities. The MoMe@school tool box would in theory allow students to assess a wider area, using the smartphone app to assess the streetscape and open spaces of the school’s neighborhood or their journeys between home and school. Such an extension would require adaptions to the concept, i.e. to include staff to accompany the children, or to integrate MoMe@school to educational programs such as “Safe Road to Schools”. Active transport has been shown in many studies to contribute largely to children’s overall physical activity levels and mental wellbeing. Investigating urban design factors that hinder or promote active transport from the children’s and potentially their parents’ point of view could be very beneficial.

MoMe@school has the potential to become a useful tool for education facilities planners as it contributes to the data gathering for the “zero” phase of project planning and implementation and helps to provide rich data about user’s behavior and perceptions for the preparation of high quality design briefs. Additionally, we suggest that this type of mobile app could not only help to gather and summarize data about school environment for use in the future design process but also serve as an extracurricular learning tool aimed to improve children’s spatial orientation/navigation skills.

References

Audrey S., Batista-Ferrer H. (2015), Healthy urban environments for children and young people: A systematic review of intervention studies. Health & Place, Bd. 36, Nr. 11 (November 2015): 97-117.

Barret P., Davies F., Zhang Y., and Barret L. (2015). The impact of classroom design on pupils' learning: Final results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Building and Environment. Volume 89 (July 2015), 118–133.

Carlson, S. A., Fulton, J. E., Lee, S. M., Maynard, L. M., Brown, D. R., Harold W. Kohl, I., & Dietz, W. H. (2008). Physical Education and Academic Achievement in Elementary School: Data From the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. American Journal of Public Health, 98(4), 721-727. doi:10.2105/ajph.2007.117176

Deinet U. (2015), Raumaneignung als Bildung im Stadtraum, in: Coelen, Thomas; Heinrich Anne Juliane; Milion, Angela (eds.), Stadtbaustein Bildung, Springer, Wiesbaden, pp. 159-66.

Driskell D. (2002), Creating Better Cities with Children and Youth. Earthscan Ltd and UNESCO, London.

Fedewa, A.L., Ahn, S. (2011). The effects of physical activity and physical fitness on children’s achievement and cognitive outcomes: a meta-analysi. In Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82(3), pp. 521–535.

Halblaub Miranda, M., & Knöll, M. (January 2016). Stadtflucht - Learning about healthy places with a location-based game. (J. Ackermann, A. Rauscher, & S. Daniel, eds.) Navigationen - Zeitschrift für Medien und Kulturwissenschaften, 16, pp. 101-18.

Halblaub Miranda M., Hardy S., Knöll M. (2015). MoMe: a context-sensitive mobile application to research spatial perception and behaviour. In Proceedings of the conference on human mobility, cognition and GIS, University of Copenhagen, 29-30.

Hessisches Kultusministerium (2012). Arbeitsfeld „Schule & Gesundheit“. Hessen 2012-2016. Grundlagen – Strategien – Meilensteine. Retrieved April 3, 2017 from www.schuleundgesundheit.hessen.de

Howie, E. K., & Pate, R. R. (2012). Physical activity and academic achievement in children: A historical perspective. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 1(3), 160-169.

Jacobs J. (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Johnson L., Adams-Becker S., Estrada V, Freeman A., Kampylis P., Vuorikari R. and Yves P. (2014), Horizon Report Europe: 2014 Schools Edition. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, & Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium.

Klima M., Reiss J., Erhorn H., and Fluch M. (2006). Gebäude sanieren – Schulen. BINE Themeninfo (January 2006).

Knöll, M., Neuheuser, K., Cleff, T., & Rudolph-Cleff, A. (13. Januar 2017). A tool to predict perceived urban stress in open public spaces. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science. Online first https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813516686971

Knöll, M., & Roe, J. (31. July 2016). Pokemon Go: a tool to help urban design improve mental health? Urban Design & Mental Health: Sanity and Urbanity.

Knöll M., Li Y., Neuheuser K, Rudolph-Cleff A. (2015). Using space syntax to analyse stress ratings of open public spaces. In Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium, (SSS’10) London: University College London, 123:1-15.

Knöll, M., Dutz, T., Hardy, S., & Göbel, S. (2014). Urban Exergames – How Architects and Serious Gaming Researchers Collaborate on the Design of Digital Games that make you move. In M. Ma, L. Jain, A. Withehead, & P. Anderson (eds.), Virtual and Augmented Reality in Healthcare 1 (S. 191-207). London: Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-54816-1_11

Knöll M. (2012), Urban Health Games. Collaborative, Expressive & Reflective. Ph.D. Dissertation. Universität Stuttgart, Fakultät Architektur und Stadtplanung - Institut Grundlagen Moderner Architektur und Entwerfen, Stuttgart.

Mau B., O'Donnell, Wickl, Pigozzi and Peterson. (2010). The Third Teacher – 79 Ways You Can Use Design to Transform Teaching and Learning. Cannon Design, VS Furniture, Bruce Mau Design.

Montag Stiftung (2017). Schulen planen und bauen – Grundlagen und Prozesse; Kapitel IV, S. 135-163.

Montag Stiftung (2013). Leitlinien für leistungsfähige Schulbauten in Deutschland. 2013.

Saarloos D., Kim J.E., Timmermans H. (2009). The Built Environment and Health: Introducing Individual Space-Time Behavior. Int. J. Environ., Res. Public Health, 6(6), 1724-1743.

School health promotion: evidence for effective action. SHE Factsheet 2.

Word Health Organisation (1995). Health Promoting Schools: A Healthy Setting for Learning, Living and Working.

Whyte, W.H. (1980), The Social Life of Small Public Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces.

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS

About the Authors

|

Marianne Halblaub Miranda is a research associate in the Urban Health Games group, Department of Architecture at the Technische Universität Darmstadt. She holds an engineering degree in architecture and urban planning from the TU Darmstadt. Her research focus is on user-centered architecture and urban design and the dynamics of the built environment and human behavior, including navigation and orientation, cognition and perception, and the influence of the built environment on its users. Some of the tools she has co-developed include MoMe, a context-sensitive mobile application to assess spatial perception and behavior in the built environment; and its adaptation for schools settings, MoMe@school. She is leading the project Active Learning Spaces, presented in this article and is part of the project PREHealth, which investigates urban open space and how people’s wishes and affordances can be put at the centre of planning to maximize their benefits for health and wellbeing. She is also co-leading an urban design unit on Universal Design and Access for All.

|

|

Maria Ustinova is currently a Consultant at the World Bank's country office in Russia, where she is actively involved in the projects in the field of education and social protection. Prior to joining the World Bank, she was a consultant for the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, as well as for various higher education projects supported by DG Education and Culture of European Commission and Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency of the European Union. She holds a double Master degree in Urban Development and International Cooperation from Darmstadt University of Technology and University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy, as well as a Masters degree in Public Administration from Higher School of Economics (Russia). Her areas of research and professional interest include urban planning and design, early childhood development, architecture of education facilities, participatory planning in education facilities design, as well as aging and intergenerational facilities planning. She is an active member of Erasmus Mundus Association and advocates for internationalization of higher education and academic mobility.

@ustiana |

|

Thomas Tregel has studied computer science at the Technische Universität Darmstadt and is a research assistant at the Multimedia Communications Lab at Technische Universität Darmstadt. His main research focus lies in the fields of automated personalization of multiplayer serious games and procedural content generation for context-based games.

|

|

Martin Knöll is professor and head of the Urban Health Games group in the Department of Architecture at Technische Universität Darmstadt. He holds a PhD from Universität Stuttgart, Germany, on health-oriented urbanism. Dr. Knöll leads the research group in building new transdisciplinary collaborations between designers and health experts to address global health challenges such as social inclusion, physically inactive lifestyles, diabetes and urban stress. Previously, Dr. Knöll was visiting scholar at the Lansdown Centre for Electronic Arts at Middlesex University, London, UK, and held a post-doc position in the Department of Architecture at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany.

@MartinKnoell |

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS