|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:14

|

CASE STUDY

Regenerative Cities: Moving Beyond Sustainability

A Los Angeles Case Study

Gunnar Hauser Hand, Roger Weber and Nathan Bluestone

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, LLP

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, LLP

Key messages for urban planning and design

The UN Brundtland report describes sustainability as the ability to meet the meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The authors propose that sustainability by definition is an insufficient framework to capture the myriad of issues and solutions required to make our cities more livable, equitable, and healthy for everyone. We need to go further than recent UN sustainability goals because the concept is still being framed within an exhausted term. It is imperative that we do more than simply sustain life, but begin to fix the mistakes of the past and heal as we grow. We must decouple inefficiencies and structural imbalances in order to promote a system that produces inclusive wellbeing and happiness. The authors present ten city design principles for regenerative cities, and identify how some of these have particular relevance for population mental health.

The UN Brundtland report describes sustainability as the ability to meet the meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The authors propose that sustainability by definition is an insufficient framework to capture the myriad of issues and solutions required to make our cities more livable, equitable, and healthy for everyone. We need to go further than recent UN sustainability goals because the concept is still being framed within an exhausted term. It is imperative that we do more than simply sustain life, but begin to fix the mistakes of the past and heal as we grow. We must decouple inefficiencies and structural imbalances in order to promote a system that produces inclusive wellbeing and happiness. The authors present ten city design principles for regenerative cities, and identify how some of these have particular relevance for population mental health.

INTRODUCTION

While the idea of regenerative cities is not new or unique, a comprehensive definition of it has not yet been fully developed. This ambiguity must be rectified in order to give elected officials, decision makers, and the general public the ability to comprehend and thereby begin the real, meaningful application of the overarching concept. This paper provides an ideological framework consisting of ten different city design principles that can be used to initiate and facilitate this much-needed public dialogue. Such a definition would also give clarity to the broader message about regenerative design. Learning from the sustainability experience (originally published in the United Nation’s 1987 Brundtland Report) and now resiliency’s slow adoption and usurpation thereof, it is imperative to clearly and concisely define the problem and how viewing decision-making through a regenerative lens can ultimately expedite the process of its ultimate implementation.

Below is a description of ten city design principles: Livability, Equity, Ecology, Nutrition, Access, Waste, Water, Resiliency, Energy and Heritage. Following each principle is an infographic, which seeks to clearly convey a complex and multi-faceted concept, strategy, and/or approach. While the description of each principle is general in nature, the infographics focus on each principle’s meaning within Los Angeles as a means to convey the ideas in a real world context. The result is a sort of regenerative cities call to action using the City and County of Los Angeles as a case study. It is important to note that this manuscript is not purely scientific, but uses data to describe how non-regenerative decisions of the past have created a cumulative impact on the built environment of today, and the only way to undo these past decisions is to rethink how we move forward in a new, data-driven, and ultimately regenerative way.

So, in order to define how to build a regenerative Los Angeles, one must first ask the question; what is a Regenerative City? Regenerative Cities is a method of urban development that seeks to build a restorative relationship with nature and create inclusive well-being; health and happiness for everyone now and in the future.

LIVABILITY

A Regenerative City takes every opportunity to improve.

For the first time in history, there are more people living in cities than not (1). This nascent century of the city has quickly become the leading driver of a global shift towards stewardship, equity, and social cohesion (2). Designing the growth of cities to enhance quality of life allows communities to define their own unique futures. Instead of a piecemeal, often contentious approach to each new development, cities must leverage market demands to simultaneously upgrade infrastructure, expand affordability, restore and protect natural environments, and enhance overall livability. By recognizing the built environment’s influence on people’s behaviour and thereby their sense of belonging, cities can dramatically contribute to mental health and happiness.

All cities utilize infrastructure investments in order to guide economic growth and development. Infrastructure remains one of the best available tools for fostering community activity, bringing people together, and improving quality of life (3). In short, strong streets are the most powerful tool in the urban design toolkit to create social cohesion and cultural identity. All great cities globally have strong, flourishing streetscapes that define the very image of their respective city (4).

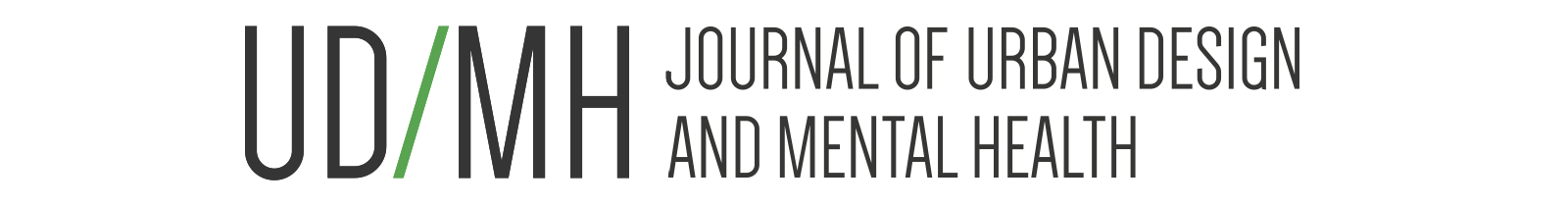

Los Angeles, too, is a city of corridors. Looking at the City of Los Angeles’ land use map, the influence of the City’s most well know roadways such as Sunset, Wilshire, Van Nuys and Figueroa can be seen (Figure 1). These corridors have framed Los Angeles’ growth for over a century and they remain the city’s strongest potential catalysts for building a unique sense of place. Yet for nearly a century Los Angeles has turned its back on these corridors through policies that have incentivized stasis, pushing new investment away from the city’s most important framework elements (5). The development along these commercial corridors has thus included minimal reinvestment outside of the West Side, Hollywood, and more recently Downtown (6). While the residential neighbourhoods directly behind these streets remain mostly intact, their commercial counterpoints are ripe for future reinvestment as described in the Southern California Association of Governments’ (SCAG), the region’s Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), Compass 2% Blueprint Plan (7).

Moving forward, LA should use its highly recognizable commercial corridors to shape community cohesion. Driving redevelopment along these public rights-of-way will not only regenerate entire neighbourhoods, but provide much needed housing and economic opportunity in proximity to infrastructure investments, leveraging them to become more legible, dynamic, walkable, and ecologically diverse places and pathways.

While the idea of regenerative cities is not new or unique, a comprehensive definition of it has not yet been fully developed. This ambiguity must be rectified in order to give elected officials, decision makers, and the general public the ability to comprehend and thereby begin the real, meaningful application of the overarching concept. This paper provides an ideological framework consisting of ten different city design principles that can be used to initiate and facilitate this much-needed public dialogue. Such a definition would also give clarity to the broader message about regenerative design. Learning from the sustainability experience (originally published in the United Nation’s 1987 Brundtland Report) and now resiliency’s slow adoption and usurpation thereof, it is imperative to clearly and concisely define the problem and how viewing decision-making through a regenerative lens can ultimately expedite the process of its ultimate implementation.

Below is a description of ten city design principles: Livability, Equity, Ecology, Nutrition, Access, Waste, Water, Resiliency, Energy and Heritage. Following each principle is an infographic, which seeks to clearly convey a complex and multi-faceted concept, strategy, and/or approach. While the description of each principle is general in nature, the infographics focus on each principle’s meaning within Los Angeles as a means to convey the ideas in a real world context. The result is a sort of regenerative cities call to action using the City and County of Los Angeles as a case study. It is important to note that this manuscript is not purely scientific, but uses data to describe how non-regenerative decisions of the past have created a cumulative impact on the built environment of today, and the only way to undo these past decisions is to rethink how we move forward in a new, data-driven, and ultimately regenerative way.

So, in order to define how to build a regenerative Los Angeles, one must first ask the question; what is a Regenerative City? Regenerative Cities is a method of urban development that seeks to build a restorative relationship with nature and create inclusive well-being; health and happiness for everyone now and in the future.

LIVABILITY

A Regenerative City takes every opportunity to improve.

For the first time in history, there are more people living in cities than not (1). This nascent century of the city has quickly become the leading driver of a global shift towards stewardship, equity, and social cohesion (2). Designing the growth of cities to enhance quality of life allows communities to define their own unique futures. Instead of a piecemeal, often contentious approach to each new development, cities must leverage market demands to simultaneously upgrade infrastructure, expand affordability, restore and protect natural environments, and enhance overall livability. By recognizing the built environment’s influence on people’s behaviour and thereby their sense of belonging, cities can dramatically contribute to mental health and happiness.

All cities utilize infrastructure investments in order to guide economic growth and development. Infrastructure remains one of the best available tools for fostering community activity, bringing people together, and improving quality of life (3). In short, strong streets are the most powerful tool in the urban design toolkit to create social cohesion and cultural identity. All great cities globally have strong, flourishing streetscapes that define the very image of their respective city (4).

Los Angeles, too, is a city of corridors. Looking at the City of Los Angeles’ land use map, the influence of the City’s most well know roadways such as Sunset, Wilshire, Van Nuys and Figueroa can be seen (Figure 1). These corridors have framed Los Angeles’ growth for over a century and they remain the city’s strongest potential catalysts for building a unique sense of place. Yet for nearly a century Los Angeles has turned its back on these corridors through policies that have incentivized stasis, pushing new investment away from the city’s most important framework elements (5). The development along these commercial corridors has thus included minimal reinvestment outside of the West Side, Hollywood, and more recently Downtown (6). While the residential neighbourhoods directly behind these streets remain mostly intact, their commercial counterpoints are ripe for future reinvestment as described in the Southern California Association of Governments’ (SCAG), the region’s Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), Compass 2% Blueprint Plan (7).

Moving forward, LA should use its highly recognizable commercial corridors to shape community cohesion. Driving redevelopment along these public rights-of-way will not only regenerate entire neighbourhoods, but provide much needed housing and economic opportunity in proximity to infrastructure investments, leveraging them to become more legible, dynamic, walkable, and ecologically diverse places and pathways.

Figure 1: City of Los Angeles General Plan Map

EQUITY

A Regenerative City facilitates equitable prosperity.

Cities are economic engines that drive innovation and productivity (8). This economic dynamism affords the social and economic mobility necessary to promote good mental health through supporting living wages, empowering the workforce, and providing stability. Optimizing capital through the creation of efficient, integrated development patterns gives citizens more expendable income and supports neighbourhoods with synergistic local economies (9). And as a human-built system, how and who that economic output impacts can be shaped by the political design of our urban areas.

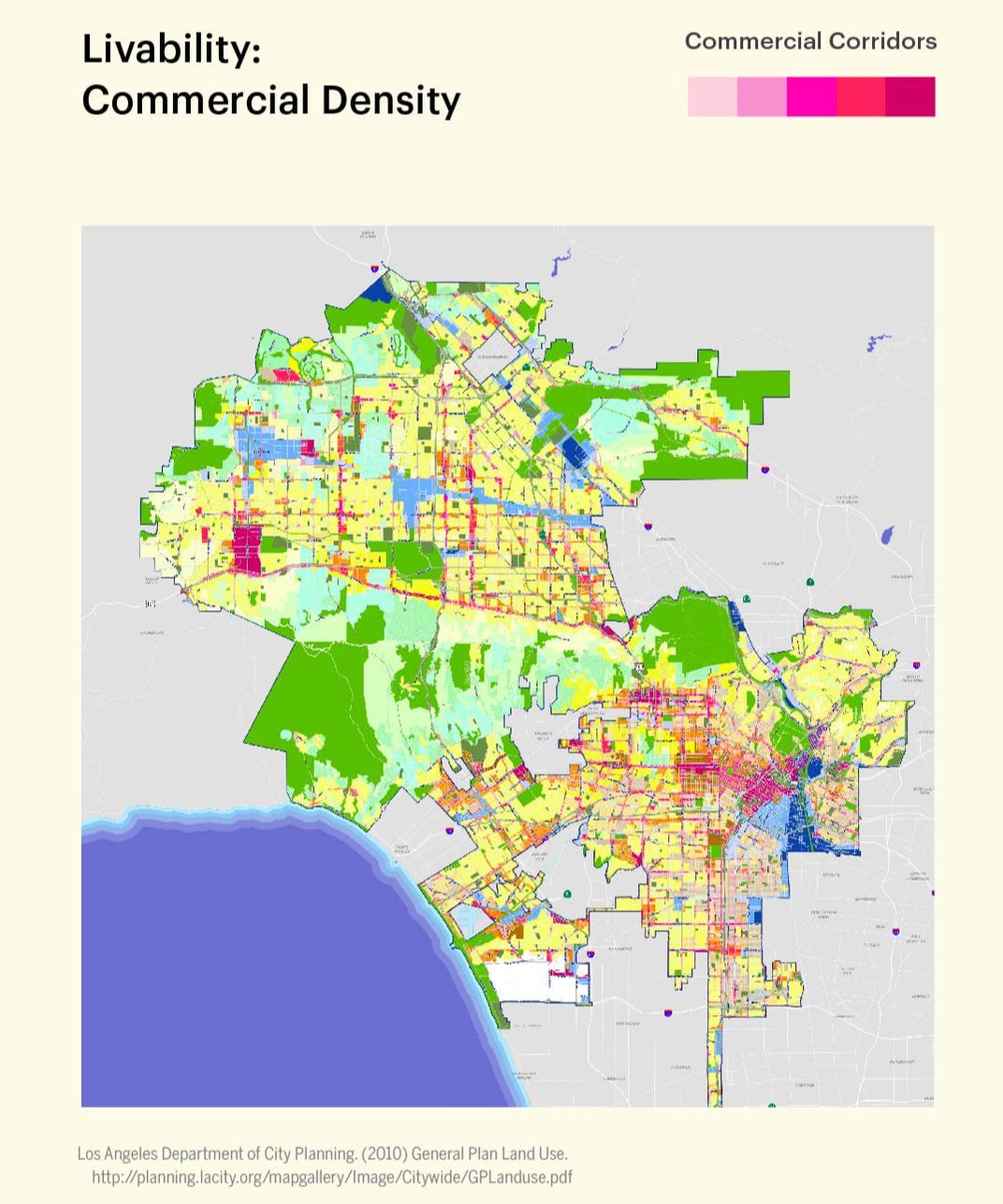

It is well documented that the density of urban areas is proportional to economic output and innovation (10). Cities organically form economic clusters as more people bring more ideas. When more people come into closer contact with one another it not only produces more sustainable living patterns and behaviours as energy use per capita are reduced (11), but also delivers the potential for good mental health as it provides more social interaction, allows for more chance encounters, and facilitates a public dialogue that creates a more collective culture. Developing an intelligent density throughout the Los Angeles region, building upon the concept of revitalizing commercial corridors along an ever expanding transit system will facilitate economic and social connectivity.

A Regenerative City facilitates equitable prosperity.

Cities are economic engines that drive innovation and productivity (8). This economic dynamism affords the social and economic mobility necessary to promote good mental health through supporting living wages, empowering the workforce, and providing stability. Optimizing capital through the creation of efficient, integrated development patterns gives citizens more expendable income and supports neighbourhoods with synergistic local economies (9). And as a human-built system, how and who that economic output impacts can be shaped by the political design of our urban areas.

It is well documented that the density of urban areas is proportional to economic output and innovation (10). Cities organically form economic clusters as more people bring more ideas. When more people come into closer contact with one another it not only produces more sustainable living patterns and behaviours as energy use per capita are reduced (11), but also delivers the potential for good mental health as it provides more social interaction, allows for more chance encounters, and facilitates a public dialogue that creates a more collective culture. Developing an intelligent density throughout the Los Angeles region, building upon the concept of revitalizing commercial corridors along an ever expanding transit system will facilitate economic and social connectivity.

Figure 2: Relationship of density, per capita patents and GDP

ECOLOGY

A Regenerative City has a symbiotic relationship with nature.

From the dawn of civilization, humankind has sought to control nature. Population growth has tested our ability to effectively develop cities in a truly sustainable way, as most interventions come with a cost to the natural environment (12). The degradation of natural systems and our access to it also degrades public mental health. This pattern of consumption must be transformed into a restorative relationship with nature whereby we heal as we grow. Instead of engineering nature to meet the needs of our world, cities must find the appropriate balance and learn to live within natural constraints.

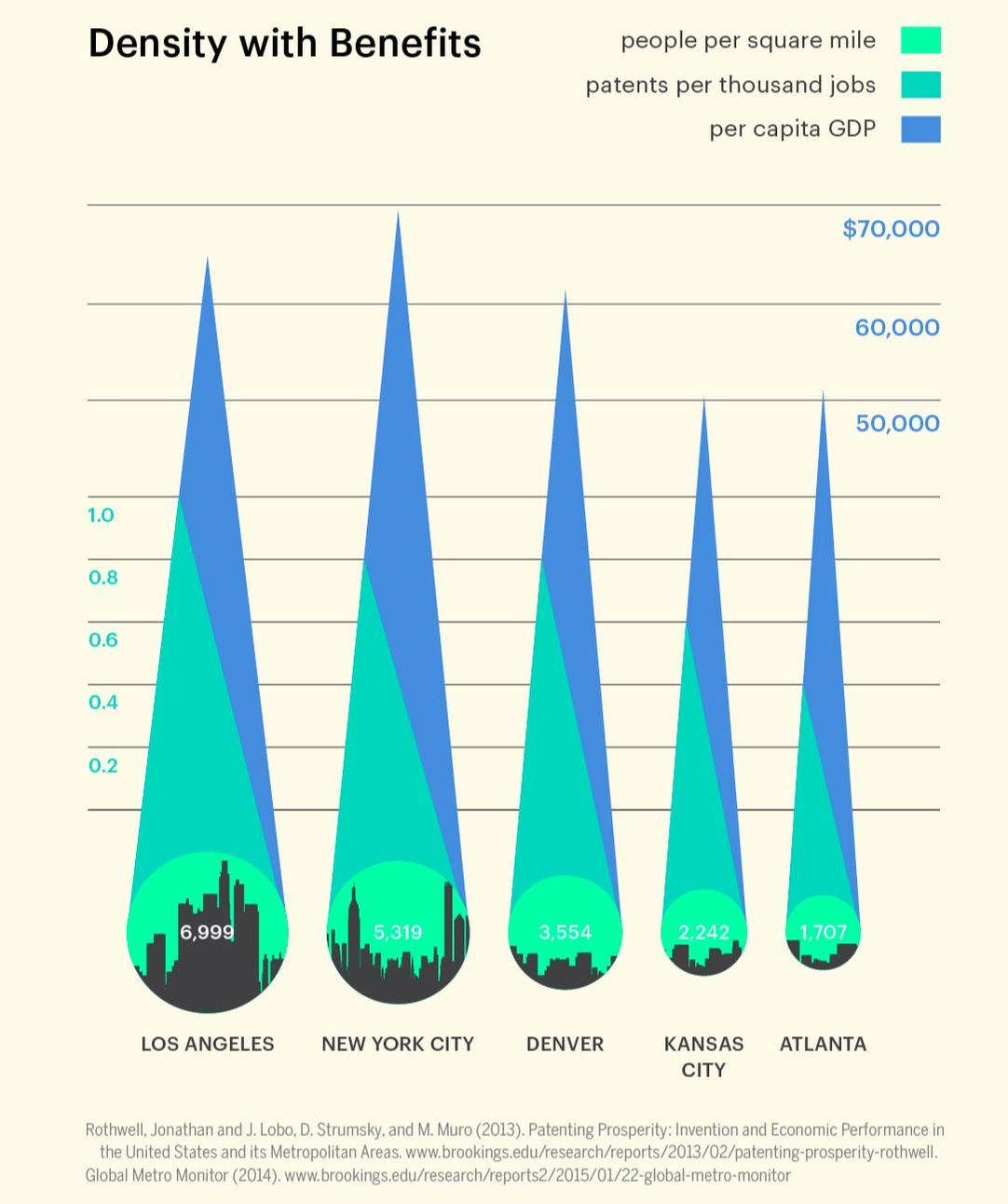

When studying the Los Angeles example, one sees a City significantly degraded by the built environment. With its car-centric culture and approach to land use development over the last 50 years, a significant proportion of land has been dedicated to the automobile (13). By simply changing the transportation hierarchy to prioritize the pedestrian through expanding transit ridership, improving walkability, and supporting advances in transportation technologies, the region could potentially reassign much of this land to more regenerative, healthy, economically beneficial, and ecologically supportive uses.

A Regenerative City has a symbiotic relationship with nature.

From the dawn of civilization, humankind has sought to control nature. Population growth has tested our ability to effectively develop cities in a truly sustainable way, as most interventions come with a cost to the natural environment (12). The degradation of natural systems and our access to it also degrades public mental health. This pattern of consumption must be transformed into a restorative relationship with nature whereby we heal as we grow. Instead of engineering nature to meet the needs of our world, cities must find the appropriate balance and learn to live within natural constraints.

When studying the Los Angeles example, one sees a City significantly degraded by the built environment. With its car-centric culture and approach to land use development over the last 50 years, a significant proportion of land has been dedicated to the automobile (13). By simply changing the transportation hierarchy to prioritize the pedestrian through expanding transit ridership, improving walkability, and supporting advances in transportation technologies, the region could potentially reassign much of this land to more regenerative, healthy, economically beneficial, and ecologically supportive uses.

Figure 3: Growth of land devoted to the automobile

NUTRITION

A Regenerative City is never hungry.

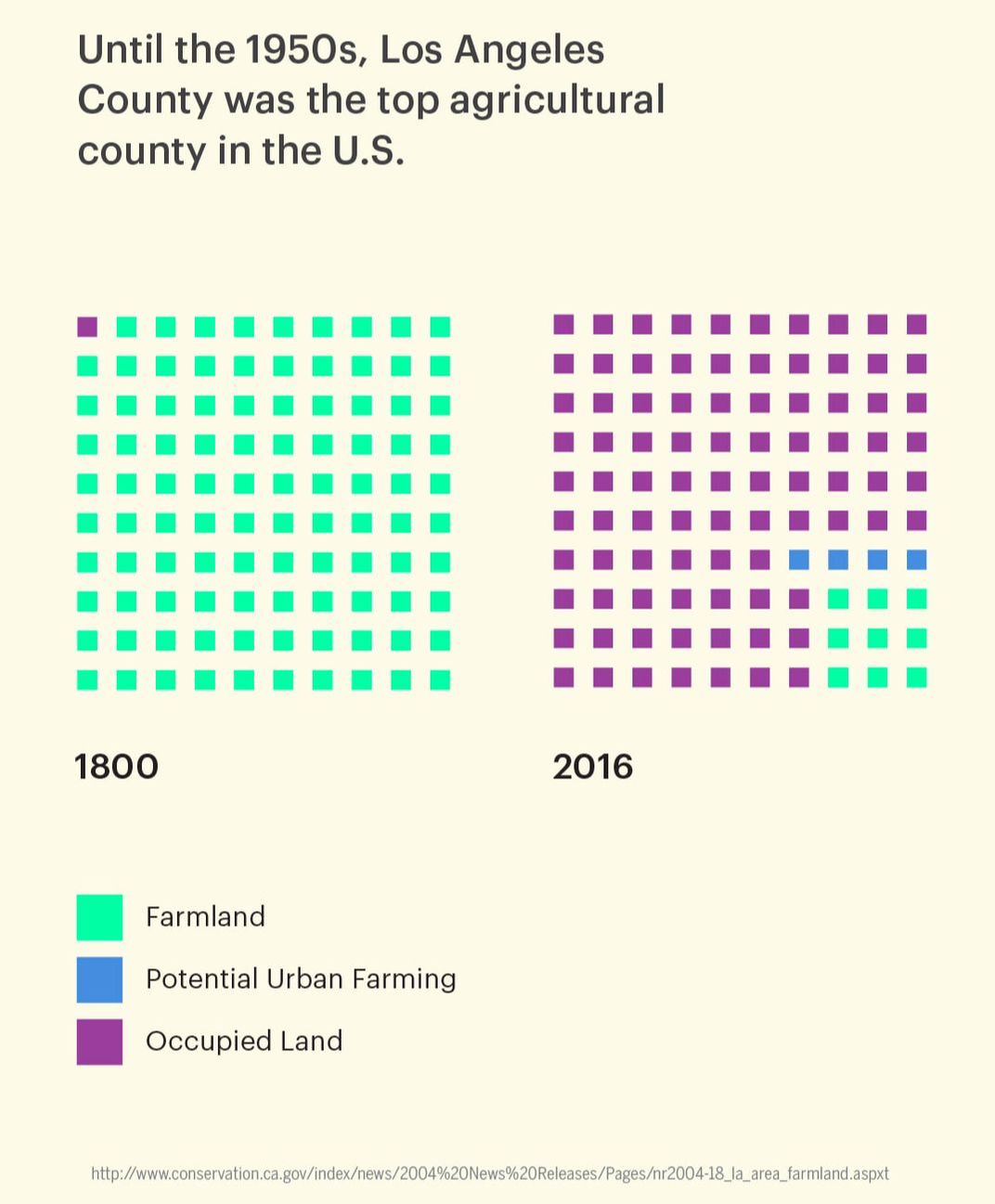

Through technological advances in agriculture, humankind has never had a problem with food supply; food scarcity and hunger is and has always been an issue of distribution and access (14). With the growing consumer preference for local, organic foods, cities can help meet this market demand by integrating food production with development. Preserving agricultural lands and retrofitting cities for urban farming will not only protect the integrity of our cities and build resilience in the local food chain, but contribute to poverty alleviation and the reduction of food scarcity (15). Edible open spaces, rooftop and vertical gardens, community co-ops, and a regional network of farms can strengthen the local economy (16), provide nutrition, increase urban access to nature, support cognitive development and contribute to a community’s health and wellbeing.

Los Angeles used to be one of the most productive agricultural Counties in the United States (17). Originally settled as 50 ranchos, Los Angeles is now predominantly single-family neighbourhoods that while still relatively dense account for most of the potentially arable land. Adding to this acreages are the 57,000 vacant parcels throughout the County, which could be better utilized to grow access to an already robust agricultural community and urban gardening culture (18).

A Regenerative City is never hungry.

Through technological advances in agriculture, humankind has never had a problem with food supply; food scarcity and hunger is and has always been an issue of distribution and access (14). With the growing consumer preference for local, organic foods, cities can help meet this market demand by integrating food production with development. Preserving agricultural lands and retrofitting cities for urban farming will not only protect the integrity of our cities and build resilience in the local food chain, but contribute to poverty alleviation and the reduction of food scarcity (15). Edible open spaces, rooftop and vertical gardens, community co-ops, and a regional network of farms can strengthen the local economy (16), provide nutrition, increase urban access to nature, support cognitive development and contribute to a community’s health and wellbeing.

Los Angeles used to be one of the most productive agricultural Counties in the United States (17). Originally settled as 50 ranchos, Los Angeles is now predominantly single-family neighbourhoods that while still relatively dense account for most of the potentially arable land. Adding to this acreages are the 57,000 vacant parcels throughout the County, which could be better utilized to grow access to an already robust agricultural community and urban gardening culture (18).

Figure 4: Change in land devoted to farming

ACCESS

A Regenerative City is open and accessible.

The dominant transportation mode has the greatest impact on the form and function of the built environment. With an increased focus on the automobile in the late 20th Century, cities became proportionally more dependent on fossil fuels, consumed more land for development, and diminished public health (19). Transitioning back to the movement of people and not cars will rebalance all mobility options merely by de-emphasizing the throughput of more often than not single-occupancy vehicle. Equalizing the role of the car will make the existing transportation system more efficient for the movement of goods and services by opening up capacity on our roadways and initiating the retrofitting of public right-of-ways so that they are both more functional as well as quality open spaces, all while building a more collaborative and opportunistic city around the interaction and lifestyle of the individual. Increasing physical activity, social interactions, and access to health services, active transportation benefits mental health.

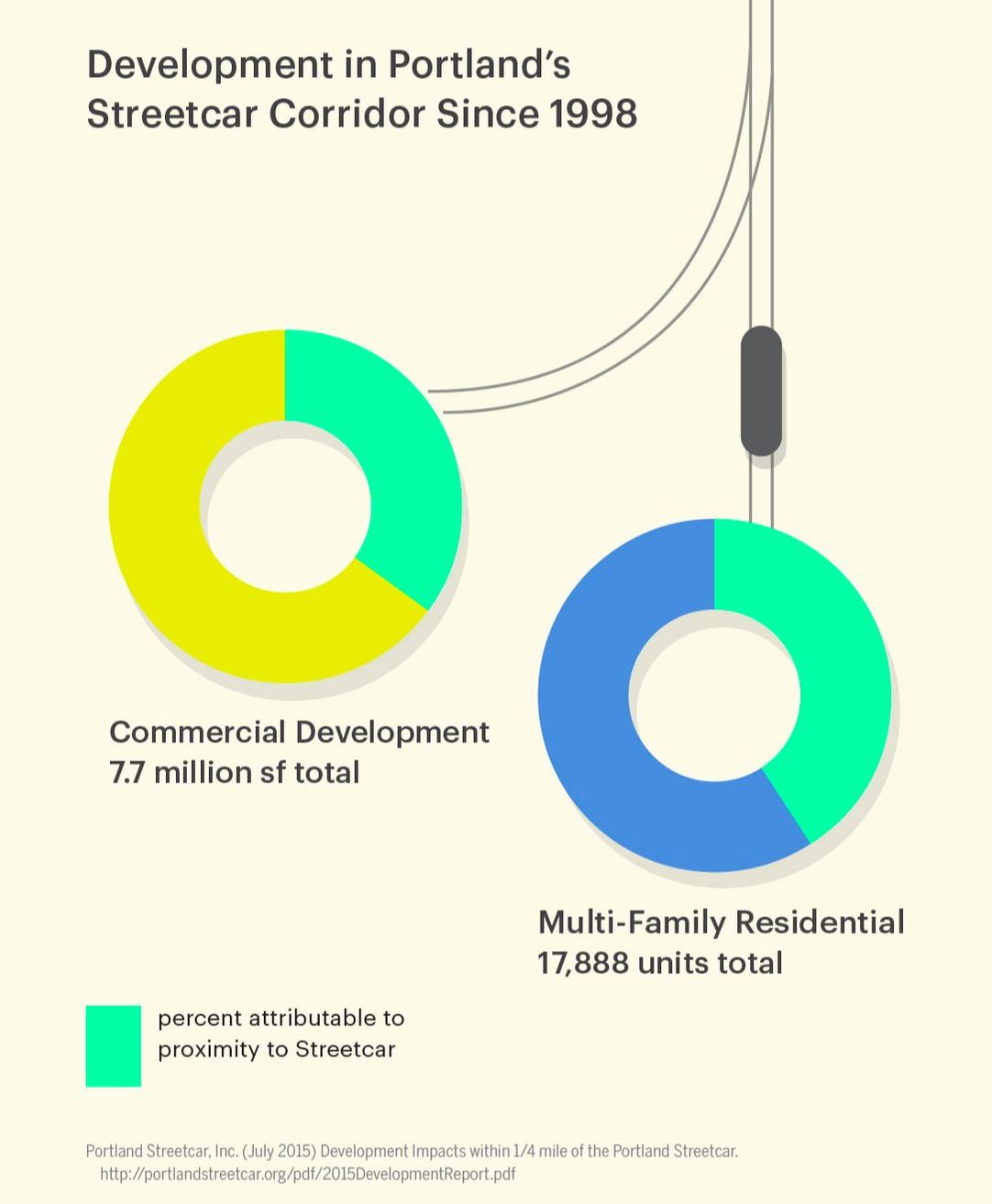

Los Angeles doesn’t have a congestion problem; it has a capacity issue. That is to say that mobility is not just a matter of transitioning people away from the automobile to alternative modes of transportation, but decreasing single occupancy vehicle use. The way in which Los Angeles has built itself up around the car facilitates a socially, economically and environmentally destructive behaviour. It creates congestion, which diminishes productivity, adds to stress during the commute, and reduces the amount of time for leisure, recreation, and family, all of which increase the burden on mental health. To address this issue, the region should encourage a new type of development that maximizes the convenience of transit riders.

Transit-oriented development (TOD) and transit-oriented communities (TOCs) are already emerging around existing transit stations and stops across the region. However, there is a missing link in the Los Angeles transit mode (bus, rapid bus, light rail, subway, heavy commuter rail, passenger rail, soon high-speed rail) portfolio. It also happens to be the modal choice that the City was historically built upon. Learning from the Portland, Oregon model, a new streetcar system can expand access to opportunity, building more inclusive and equitable communities within the inner ring “suburbs”, and creating a zone of redevelopment opportunity (20). A neighbourhood-serving streetcar system adds a new mobility choice in and around Downtown, providing seamless transit to Downtown adjacent communities, all while aligning with aforementioned streetscape retrofits.

A Regenerative City is open and accessible.

The dominant transportation mode has the greatest impact on the form and function of the built environment. With an increased focus on the automobile in the late 20th Century, cities became proportionally more dependent on fossil fuels, consumed more land for development, and diminished public health (19). Transitioning back to the movement of people and not cars will rebalance all mobility options merely by de-emphasizing the throughput of more often than not single-occupancy vehicle. Equalizing the role of the car will make the existing transportation system more efficient for the movement of goods and services by opening up capacity on our roadways and initiating the retrofitting of public right-of-ways so that they are both more functional as well as quality open spaces, all while building a more collaborative and opportunistic city around the interaction and lifestyle of the individual. Increasing physical activity, social interactions, and access to health services, active transportation benefits mental health.

Los Angeles doesn’t have a congestion problem; it has a capacity issue. That is to say that mobility is not just a matter of transitioning people away from the automobile to alternative modes of transportation, but decreasing single occupancy vehicle use. The way in which Los Angeles has built itself up around the car facilitates a socially, economically and environmentally destructive behaviour. It creates congestion, which diminishes productivity, adds to stress during the commute, and reduces the amount of time for leisure, recreation, and family, all of which increase the burden on mental health. To address this issue, the region should encourage a new type of development that maximizes the convenience of transit riders.

Transit-oriented development (TOD) and transit-oriented communities (TOCs) are already emerging around existing transit stations and stops across the region. However, there is a missing link in the Los Angeles transit mode (bus, rapid bus, light rail, subway, heavy commuter rail, passenger rail, soon high-speed rail) portfolio. It also happens to be the modal choice that the City was historically built upon. Learning from the Portland, Oregon model, a new streetcar system can expand access to opportunity, building more inclusive and equitable communities within the inner ring “suburbs”, and creating a zone of redevelopment opportunity (20). A neighbourhood-serving streetcar system adds a new mobility choice in and around Downtown, providing seamless transit to Downtown adjacent communities, all while aligning with aforementioned streetscape retrofits.

Figure 5: Induced streetcar development

WASTE

A Regenerative City is a closed loop system.

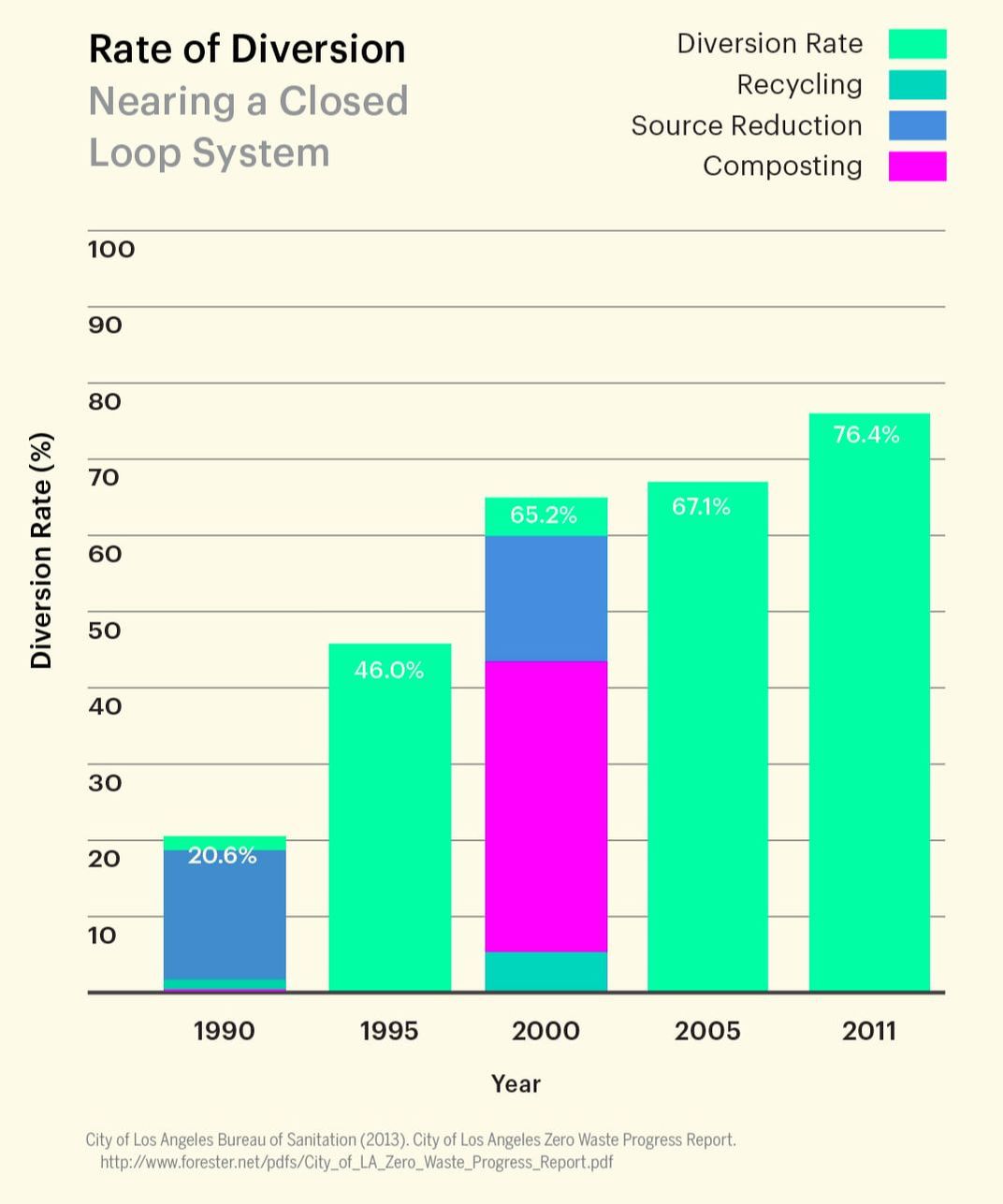

Any externality of a system is wasted energy, effort, and time. Transforming waste into a resource is a challenge for cities as it requires a shift in both perception and approach. From procurement to disposal, eliminating waste means process improvement, effective service delivery, and citizen satisfaction. Technology, smart city networks, and quality customer service can all support the business of running a city, but cities cannot eliminate waste in a vacuum. Cities must also engage the private sector to leverage their knowledge, know-how, and capabilities in order to partner in the design and realization of a more profitable city.

In large part to State mandates, both the City and County of Los Angeles have a strong trend of diverting waste from landfills (21). As diversion rates move closer and closer to 100%, it becomes increasingly difficult to obtain the ultimate goal of zero waste. While the County’s few remaining landfills still have decades of capacity, the region has already looked ahead to the closing and reclaiming of these sites and developed a strategy to ship waste out of the County via train and truck (22). In order to prevent this inevitability, the region has previously and can in the future consider waste to energy for example. This system holds the potential, albeit with some of its own challenges for a zero waste Los Angeles.

A Regenerative City is a closed loop system.

Any externality of a system is wasted energy, effort, and time. Transforming waste into a resource is a challenge for cities as it requires a shift in both perception and approach. From procurement to disposal, eliminating waste means process improvement, effective service delivery, and citizen satisfaction. Technology, smart city networks, and quality customer service can all support the business of running a city, but cities cannot eliminate waste in a vacuum. Cities must also engage the private sector to leverage their knowledge, know-how, and capabilities in order to partner in the design and realization of a more profitable city.

In large part to State mandates, both the City and County of Los Angeles have a strong trend of diverting waste from landfills (21). As diversion rates move closer and closer to 100%, it becomes increasingly difficult to obtain the ultimate goal of zero waste. While the County’s few remaining landfills still have decades of capacity, the region has already looked ahead to the closing and reclaiming of these sites and developed a strategy to ship waste out of the County via train and truck (22). In order to prevent this inevitability, the region has previously and can in the future consider waste to energy for example. This system holds the potential, albeit with some of its own challenges for a zero waste Los Angeles.

Figure 6: City of Los Angeles waste diversion rates

WATER

A Regenerative City cleans more water than it consumes.

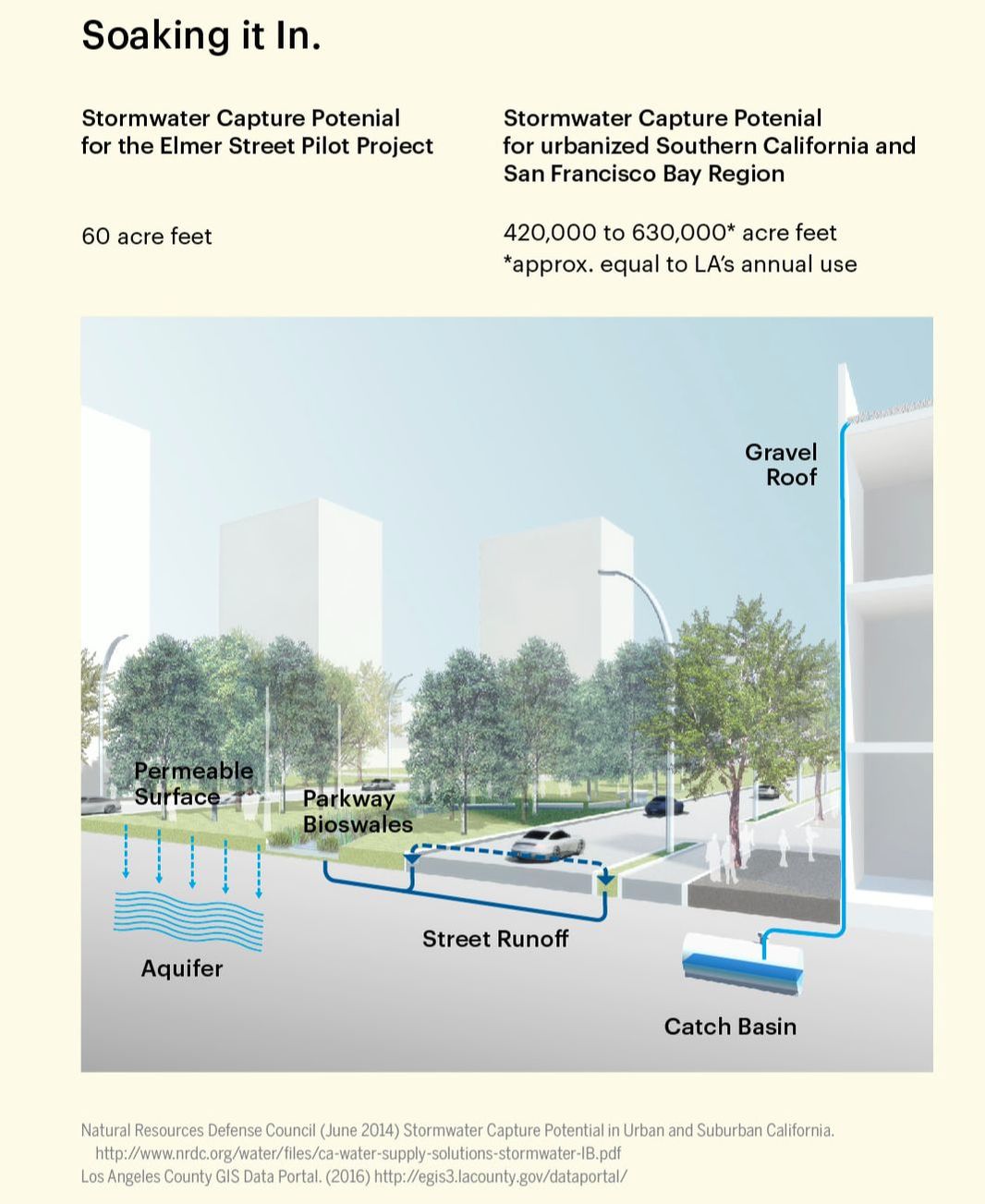

Fresh water is the earth’s most precious resource. Unfortunately, it is critically undervalued as a commodity and is often costly and over-engineered to the detriment of its natural functionality. Minimizing impermeable surfaces, maximizing natural recharge, and utilizing stormwater as a resource as opposed to a threat not only creates an opportunity to deepen our human connection to nature, but engage water ecology for the betterment of the built environment (23). Additionally, our buildings must go beyond simply managing water on-site to become themselves infrastructure for water recycling and regeneration. We must leverage water not just for our survival, but as an urban design tool to bring us closer to nature in cities and thus promote good public mental health.

With the vast majority of water in Los Angeles being imported from either Northern California or the arid Western United States via three aqueducts, the region is already well beyond its carrying capacity (24).

A Regenerative City cleans more water than it consumes.

Fresh water is the earth’s most precious resource. Unfortunately, it is critically undervalued as a commodity and is often costly and over-engineered to the detriment of its natural functionality. Minimizing impermeable surfaces, maximizing natural recharge, and utilizing stormwater as a resource as opposed to a threat not only creates an opportunity to deepen our human connection to nature, but engage water ecology for the betterment of the built environment (23). Additionally, our buildings must go beyond simply managing water on-site to become themselves infrastructure for water recycling and regeneration. We must leverage water not just for our survival, but as an urban design tool to bring us closer to nature in cities and thus promote good public mental health.

With the vast majority of water in Los Angeles being imported from either Northern California or the arid Western United States via three aqueducts, the region is already well beyond its carrying capacity (24).

Figure 7: Where LA Metro draws its water

In order to reduce its reliance on imported water, Los Angeles can change its perception of the very limited rainfall that does occur in this Mediterranean climate, as well as water recycling infrastructure. A report from the National Resource Defence Council (NRDC) stated that a fully realized stormwater management system in Los Angeles could supply approximately a third of the City’s water needs at nearly a third of the cost of imported water (25). For decades stormwater was viewed as a nuisance, and the goal was to maximize its flow out into the ocean to prevent damage and injury caused by flash flooding. Using complete, green streets and other low-impact development best practices to retrofit existing roadways will not only improve the livability and ecology of Los Angeles by both appreciating the public right-of-way as more than a system for mobility, but the region’s most valuable open space, and serve as a link from large regional parks into park poor urban neighbourhoods, but also create a system of permeable surfaces and recharge areas that reduce the risk of flooding allowing for the naturalization of the County’s channelized waterways.

Figure 8: Green infrastructure diagram

RESILIENCY

A Regenerative City is responsive.

From natural disasters to broken water mains, cities must be nimble and address many issues at once. More than being prepared, cities must also be proactive in order to generate real, meaningful, and positive progress. Cities must be proactive to effect real, meaningful change. The role of big, open data is imperative for the resilient city as it represents a wealth of information that can be leveraged to improve communications, foster innovation, generate economic activity, and enhance livability. An informed decision-making process is critical to maximize a city’s impact with increasingly constrained resources.

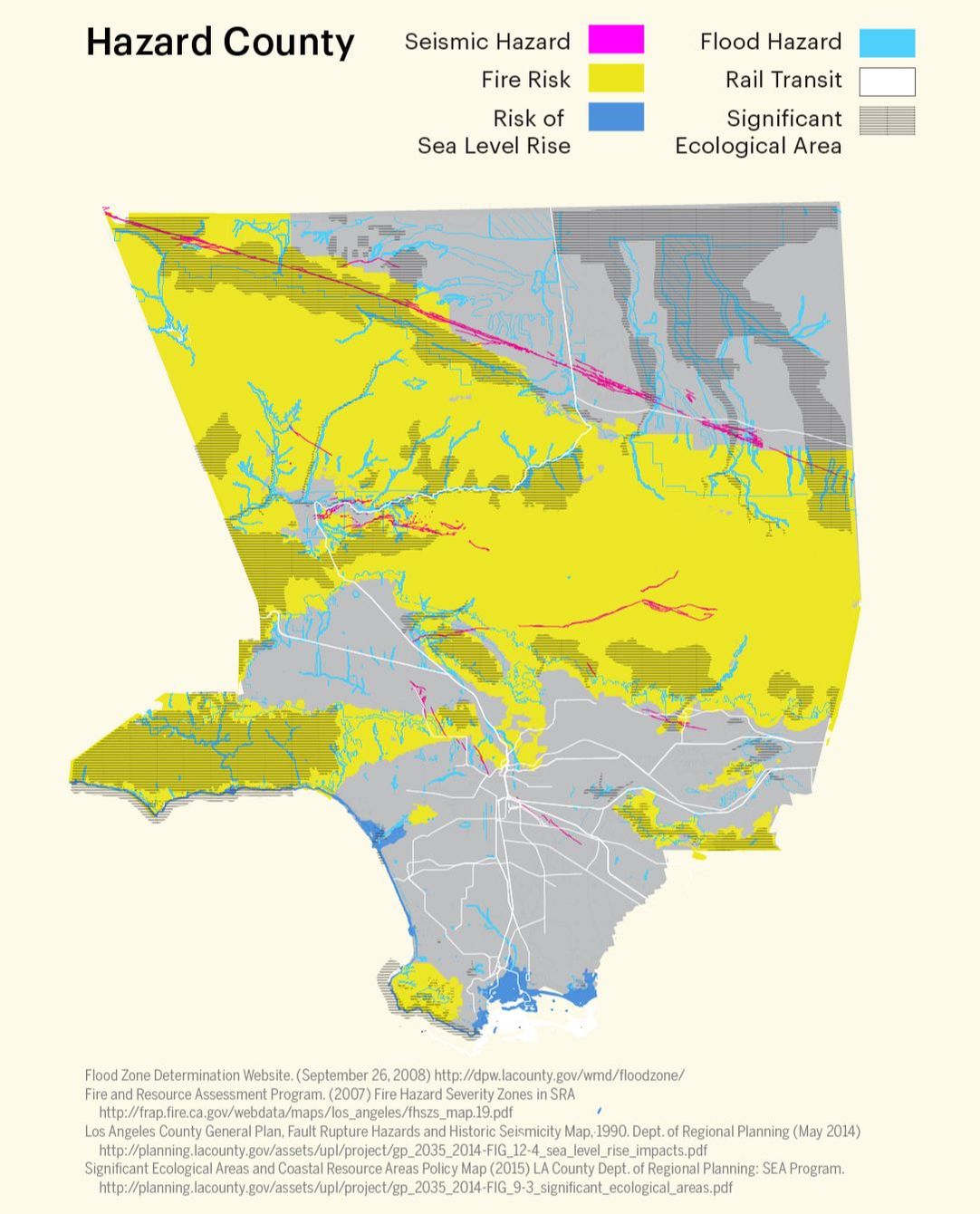

Looking at a map of Los Angeles County, there is relatively little undeveloped land that is not susceptible to some form of natural hazard (26). And layering upon that map the existing, under construction, and planned transit system, what emerges is a region that must focus development inward to optimize existing infrastructure while minimizing the costs of putting its citizens in peril. Using this information to prioritize future growth, existing retrofits and long-term buyout schemes is critical to long-term resilience. Sharing this information has an added benefit of making the public more prepared and creating a stronger sense of certainty that can reduce anxiety, minimize trauma, and promote public health.

A Regenerative City is responsive.

From natural disasters to broken water mains, cities must be nimble and address many issues at once. More than being prepared, cities must also be proactive in order to generate real, meaningful, and positive progress. Cities must be proactive to effect real, meaningful change. The role of big, open data is imperative for the resilient city as it represents a wealth of information that can be leveraged to improve communications, foster innovation, generate economic activity, and enhance livability. An informed decision-making process is critical to maximize a city’s impact with increasingly constrained resources.

Looking at a map of Los Angeles County, there is relatively little undeveloped land that is not susceptible to some form of natural hazard (26). And layering upon that map the existing, under construction, and planned transit system, what emerges is a region that must focus development inward to optimize existing infrastructure while minimizing the costs of putting its citizens in peril. Using this information to prioritize future growth, existing retrofits and long-term buyout schemes is critical to long-term resilience. Sharing this information has an added benefit of making the public more prepared and creating a stronger sense of certainty that can reduce anxiety, minimize trauma, and promote public health.

Figure 9: Natural hazards map compilation

ENERGY

A Regenerative City produces more energy than it consumes.

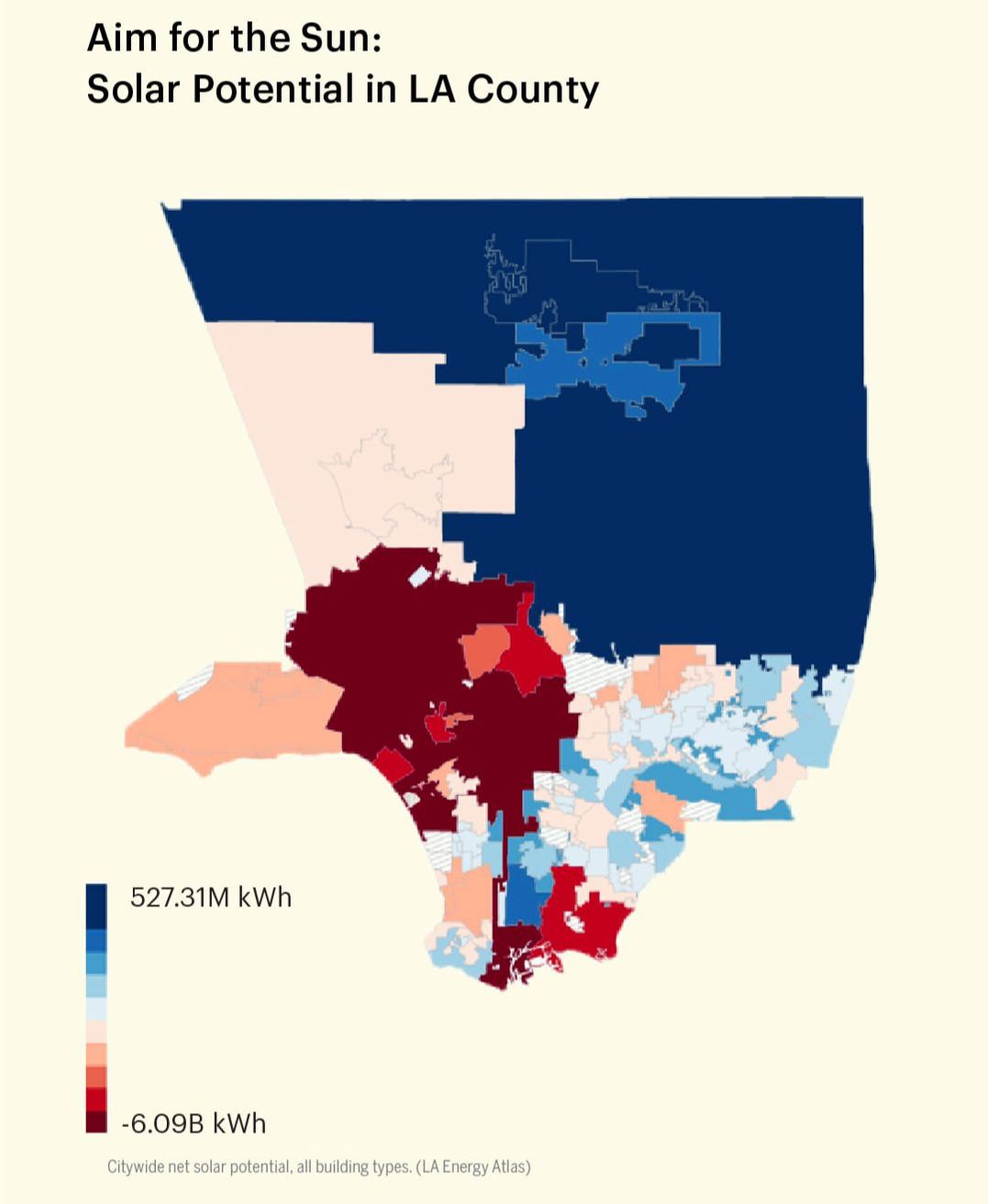

Clean, renewable energy is the dilemma of the 21st Century. Cities must diversify their power systems, thereby equally distributing risk, production, and storage. Cities must also remain connected, but begin to decouple themselves from a national grid distribution network so that they can become energy independent and more resilient during power failures.

In sunny southern California, the most obvious opportunity for renewable energy production is solar power. With a focus on solar, there is enough identified rooftops across the existing built environment to power the entire region on top of the nearly 1400 megawatts of renewable production currently in the County (27). This abundance of solar, and to a lesser degree wind and tidal power makes both “dirty” and large-scale production obsolete, but increases the need for power storage and smaller scale, combined district energy models.

The district energy approach also creates a more resilient and robust local economy by providing an additional revenue source for property owners while creating new job opportunities and producing an increased level of stability that is beneficial to general mental well-being.

A Regenerative City produces more energy than it consumes.

Clean, renewable energy is the dilemma of the 21st Century. Cities must diversify their power systems, thereby equally distributing risk, production, and storage. Cities must also remain connected, but begin to decouple themselves from a national grid distribution network so that they can become energy independent and more resilient during power failures.

In sunny southern California, the most obvious opportunity for renewable energy production is solar power. With a focus on solar, there is enough identified rooftops across the existing built environment to power the entire region on top of the nearly 1400 megawatts of renewable production currently in the County (27). This abundance of solar, and to a lesser degree wind and tidal power makes both “dirty” and large-scale production obsolete, but increases the need for power storage and smaller scale, combined district energy models.

The district energy approach also creates a more resilient and robust local economy by providing an additional revenue source for property owners while creating new job opportunities and producing an increased level of stability that is beneficial to general mental well-being.

Figure 10: Solar power generation opportunity

HERITAGE

A Regenerative City preserves and redefines its history.

The built environment is a living organism that is constantly changing. With a multitude of actors living within it, applying their imprint on it, and/or actively changing it, cities are a window into our cultural history. They are the embodiment of the influences of past actors. Preserving this historical context is not only sustainable, but imperative for the creation of a cultural identity that creates social cohesion and mutual dependence, which in turn support individual mental health.

Los Angeles has been likened to an ever-rotating movie set. It is always in flux, and always redefining itself. It does so, however, at the cost of the built environment. This never ending quest for newness creates a culture that undervalues the relics of the past. Lost in this process is a recognition and respect for the heritage of the place.

CONCLUSION

Is a Regenerative City a utopian idea?

Absolutely. It provides a vision for all municipalities and communities to aspire. Like all things, incremental implementation is the best and sometimes only way forward. Each city and region will have to define how its global context contributes to its own regenerative identity and strategy. What it means to be regenerative is as equally diverse as the uniqueness of each city. What is known is that a regenerative city is livable, equitable and accessible by all. This transparency and openness to new ideas, cultures and practices promotes both the public and individual health and their pursuit of happiness.

In Los Angeles, these ten city design principles are applied across both the City and County of Los Angeles using the above infographics to display each principle’s intended purpose and application. Each is meant to transcend policy, design and direct action. While the above description of a regenerative city advances a larger discussion, its application to a specific context, in this case Los Angeles, allows for examples and other strategies to be thoroughly developed in the future. It also provides a connection from a modernist perspective on problem solving, its unintended and cumulative consequences, and how something more than just sustainability is needed to address these often structural civic, cultural and even individual issues.

Regardless of the context, monitoring progress will require an ongoing conversation about what data sets best illustrate trends and lead to the most informed decision-making process moving forward. Cities, including Los Angeles, must not only collect (existing, new, and sensor data) and mine “big” data, but also go through a process to define its desired outcomes and then set up a “smart city” dashboard to monitor implementation.

There are any number of data sets that would point to progress in creating a more regenerative city. Each of the ten principles could have their own data sets. Some key inputs may include, but are not limited to, citizen satisfaction, transit happiness, small business generation, air quality, obesity rates, vehicle miles travelled, waste diversion rates, stormwater run-off, response times, and energy demand to name a few. Future research is needed to develop an effective monitoring program.

This paper was the first step to define this Regenerative Cities process. The authors will continue to engage in a dialogue of discovery within the design community, with our peers, at the City and amongst the general public in order to expand and appropriately frame the conversation of Los Angeles as it moves from past, to present, and into a regenerative future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special acknowledgements to Skidmore, Ownings, & Merrill, LLP, the SOM City Lab and its Director, Roger Weber, as well as Nathan Bluestone for his diligence translating data sets and ideas into supporting graphics.

REFERENCES

The information used to develop the above infographics are sited within each image. They are included again in order of their use in the above paper in the reference section below, as well as several important readings that inspired our City Design thinking:

1. United Nation Population Fund (UNFPA), (2007). State of World Population 2007: p. 1-3.

2. Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings Institute, (2008). Metro Nation; How US Metropolitan Areas Fuel American Prosperity: p. 22-45.

3. Bigio, A. and B. Dahiya, (2004). Urban Environment and Infrastructure; Toward Livable Cities: p. 5-8.

4. Lynch, K., (1960). The Image of the City: p. 95-99.

5. N. Wasi and M. White, (2005). Property Tax Limitations and Mobilty: The Lock-in Effect of California’s Proposition 13: p. 17-21.

6. Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation (2016). 2016-2017 Economic forecast and industry outlook. LAEDC Kyser Center for Economic Research: p.73-85.

7. Southern California Association of Governments, (2008). Regional Comprehensive Plan, Land Use and Housing Chapter: p.14-22.

8. Glaeser, E., (2014). Cities: Engines of Innovation. Scientific American.

9. Choi, L., (2011). Income Inequality’s Impact on Community Development. Community Investment, Volume 23 Number 2 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco: p. 8-10.

10. Rothwell, J, Strumsky, D., Lobo, J., and M. Muro (2013). Patenting Prosperity: invention and Economic Performance in the United State and its Metropolitan Areas: p. 16-24.

11. Parshall, L., Haraguchi, M., Rosenzweigh, C. and S. Hammer, (2011). The Contribution of Urban Areas to Climate Change New York City Case Study. Cities and Climate Change: Global Report on Human Settlements 2011: p. 16-20.

12. Bartlett, A., (2016). Reflections on sustainability, population growth, and the environment. Negative Population Growth Forum Paper: p. 6-11.

13. Chester, M., Fraser, A., Matute, J., Flower, C. and R. Pendyala, (2015). Parking Infrastructure: A Constraint on or Opportunity for Urban Redevelopment? A Study of Los Angeles County Parking Supply and Growth. Journal of the American Planning Association, pp. 268-286.

14. Leathers, H., and P. Foster (2009). The world food problem: toward ending undernutrition in the third world: p.133.

15. Hoornweg, D., and P. Munro-Faure (2008). Urban agriculture for sustainable poverty alleviation and food security, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: p. 15-16.

16. Los Angeles Food Policy Council (2013). Los Angeles food system snapshot 2013: a baseline report of the Los Angeles regional foodshed: p.21-36.

17. The State of California Department of Conservation, (2012). Farmland Mapping and Monitoring Program.

18. Marcellino, E. (2015). Los Angeles County plans to lower property taxes on urban lots used for farming. Los Angeles Daily News:

19. Frumkin, H. (2002). Urban sprawl and public health. Public Health Reports, Volume 117: p. 202-207.

20. Portland Streetcar Inc. and EcoNorthwest, (2015). Development Impacts within ¼ mile of the Portland Streetcar.

21. City of Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation, (2013). City of Los Angeles Zero Waste Progress Report: p. 7-28.

22. County of Los Angeles Department of Public Works (2012). Countywide Integrated Waste Management Plan. 2012 Annual Report: p. 10-42.

23. Pacific Institute and the National Resource Defense Council (2014). Urban water conservation and efficiency potential in California: p. 1-6.

24. Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, (2010). Urban Water Management Plan: p. 3-10.

25. Natural Resource Defense Council, (20140). Stormwater Capture Potential in Urban and Suburban California: p. 2-6.

26. Los Angeles County Department of Regional Planning, (2015). General Plan Maps; Flood Zones, Fire Hazard Severity Zones, Fault Rupture Hazard and Historic Seismicity, Significant Ecological Areas.

27. Environmental Defense Fund and UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs (2014). Los Angeles solar and efficient report (LASER): an atlas of investment potential in Los Angeles County: p. 8-10.

A Regenerative City preserves and redefines its history.

The built environment is a living organism that is constantly changing. With a multitude of actors living within it, applying their imprint on it, and/or actively changing it, cities are a window into our cultural history. They are the embodiment of the influences of past actors. Preserving this historical context is not only sustainable, but imperative for the creation of a cultural identity that creates social cohesion and mutual dependence, which in turn support individual mental health.

Los Angeles has been likened to an ever-rotating movie set. It is always in flux, and always redefining itself. It does so, however, at the cost of the built environment. This never ending quest for newness creates a culture that undervalues the relics of the past. Lost in this process is a recognition and respect for the heritage of the place.

CONCLUSION

Is a Regenerative City a utopian idea?

Absolutely. It provides a vision for all municipalities and communities to aspire. Like all things, incremental implementation is the best and sometimes only way forward. Each city and region will have to define how its global context contributes to its own regenerative identity and strategy. What it means to be regenerative is as equally diverse as the uniqueness of each city. What is known is that a regenerative city is livable, equitable and accessible by all. This transparency and openness to new ideas, cultures and practices promotes both the public and individual health and their pursuit of happiness.

In Los Angeles, these ten city design principles are applied across both the City and County of Los Angeles using the above infographics to display each principle’s intended purpose and application. Each is meant to transcend policy, design and direct action. While the above description of a regenerative city advances a larger discussion, its application to a specific context, in this case Los Angeles, allows for examples and other strategies to be thoroughly developed in the future. It also provides a connection from a modernist perspective on problem solving, its unintended and cumulative consequences, and how something more than just sustainability is needed to address these often structural civic, cultural and even individual issues.

Regardless of the context, monitoring progress will require an ongoing conversation about what data sets best illustrate trends and lead to the most informed decision-making process moving forward. Cities, including Los Angeles, must not only collect (existing, new, and sensor data) and mine “big” data, but also go through a process to define its desired outcomes and then set up a “smart city” dashboard to monitor implementation.

There are any number of data sets that would point to progress in creating a more regenerative city. Each of the ten principles could have their own data sets. Some key inputs may include, but are not limited to, citizen satisfaction, transit happiness, small business generation, air quality, obesity rates, vehicle miles travelled, waste diversion rates, stormwater run-off, response times, and energy demand to name a few. Future research is needed to develop an effective monitoring program.

This paper was the first step to define this Regenerative Cities process. The authors will continue to engage in a dialogue of discovery within the design community, with our peers, at the City and amongst the general public in order to expand and appropriately frame the conversation of Los Angeles as it moves from past, to present, and into a regenerative future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special acknowledgements to Skidmore, Ownings, & Merrill, LLP, the SOM City Lab and its Director, Roger Weber, as well as Nathan Bluestone for his diligence translating data sets and ideas into supporting graphics.

REFERENCES

The information used to develop the above infographics are sited within each image. They are included again in order of their use in the above paper in the reference section below, as well as several important readings that inspired our City Design thinking:

1. United Nation Population Fund (UNFPA), (2007). State of World Population 2007: p. 1-3.

2. Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings Institute, (2008). Metro Nation; How US Metropolitan Areas Fuel American Prosperity: p. 22-45.

3. Bigio, A. and B. Dahiya, (2004). Urban Environment and Infrastructure; Toward Livable Cities: p. 5-8.

4. Lynch, K., (1960). The Image of the City: p. 95-99.

5. N. Wasi and M. White, (2005). Property Tax Limitations and Mobilty: The Lock-in Effect of California’s Proposition 13: p. 17-21.

6. Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation (2016). 2016-2017 Economic forecast and industry outlook. LAEDC Kyser Center for Economic Research: p.73-85.

7. Southern California Association of Governments, (2008). Regional Comprehensive Plan, Land Use and Housing Chapter: p.14-22.

8. Glaeser, E., (2014). Cities: Engines of Innovation. Scientific American.

9. Choi, L., (2011). Income Inequality’s Impact on Community Development. Community Investment, Volume 23 Number 2 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco: p. 8-10.

10. Rothwell, J, Strumsky, D., Lobo, J., and M. Muro (2013). Patenting Prosperity: invention and Economic Performance in the United State and its Metropolitan Areas: p. 16-24.

11. Parshall, L., Haraguchi, M., Rosenzweigh, C. and S. Hammer, (2011). The Contribution of Urban Areas to Climate Change New York City Case Study. Cities and Climate Change: Global Report on Human Settlements 2011: p. 16-20.

12. Bartlett, A., (2016). Reflections on sustainability, population growth, and the environment. Negative Population Growth Forum Paper: p. 6-11.

13. Chester, M., Fraser, A., Matute, J., Flower, C. and R. Pendyala, (2015). Parking Infrastructure: A Constraint on or Opportunity for Urban Redevelopment? A Study of Los Angeles County Parking Supply and Growth. Journal of the American Planning Association, pp. 268-286.

14. Leathers, H., and P. Foster (2009). The world food problem: toward ending undernutrition in the third world: p.133.

15. Hoornweg, D., and P. Munro-Faure (2008). Urban agriculture for sustainable poverty alleviation and food security, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: p. 15-16.

16. Los Angeles Food Policy Council (2013). Los Angeles food system snapshot 2013: a baseline report of the Los Angeles regional foodshed: p.21-36.

17. The State of California Department of Conservation, (2012). Farmland Mapping and Monitoring Program.

18. Marcellino, E. (2015). Los Angeles County plans to lower property taxes on urban lots used for farming. Los Angeles Daily News:

19. Frumkin, H. (2002). Urban sprawl and public health. Public Health Reports, Volume 117: p. 202-207.

20. Portland Streetcar Inc. and EcoNorthwest, (2015). Development Impacts within ¼ mile of the Portland Streetcar.

21. City of Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation, (2013). City of Los Angeles Zero Waste Progress Report: p. 7-28.

22. County of Los Angeles Department of Public Works (2012). Countywide Integrated Waste Management Plan. 2012 Annual Report: p. 10-42.

23. Pacific Institute and the National Resource Defense Council (2014). Urban water conservation and efficiency potential in California: p. 1-6.

24. Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, (2010). Urban Water Management Plan: p. 3-10.

25. Natural Resource Defense Council, (20140). Stormwater Capture Potential in Urban and Suburban California: p. 2-6.

26. Los Angeles County Department of Regional Planning, (2015). General Plan Maps; Flood Zones, Fire Hazard Severity Zones, Fault Rupture Hazard and Historic Seismicity, Significant Ecological Areas.

27. Environmental Defense Fund and UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs (2014). Los Angeles solar and efficient report (LASER): an atlas of investment potential in Los Angeles County: p. 8-10.

About the Authors

|

Gunnar Hand is a city and regional planner, and passionate all-around community organizer. He has cultivated his interest in the built environment from a young age and transformed it into action and positive change. From starting his own property reinvestment business and launching several rail-based transit advocacy non-profits, to promoting clean energy alternatives and neighborhood improvements on various boards, Gunnar is a problem solver. He is deeply engaged with his clients and his community, building partnerships and identifying strategic initiatives for innovative and effective implementation. Gunnar is always expanding his knowledge and understanding of the built environment and civic systems in order to find new ways to make them better. As an urban planner, he understands that functional, integrated and equitable communities can foster a higher quality of life for all people. Gunnar seeks to facilitate, create and design places that have a positive and sustainable impact on society and the world.

|

|

Roger Weber is the lead urban designer in the Washington, DC office of SOM and leads SOM’s Urban Policy practice area. He specializes in large scale master planning, real estate and regulatory strategies. He has experience in urban design, project strategy, guidelines and zoning, global positioning, and comprehensive physical, economic, environmental, and technical planning for some of the largest public and private development projects in the world. His responsibilities include long-term visioning, economic analysis, schematic land planning, urban design, master planning, comprehensive planning, programming, writing, technical and illustrated drawing, guideline creation, book and report generation, plot sheets, coordination between SOM teams, offices, and subconsultants.

|

|

Nathan Bluestone is senior graphic designer at SOM. With 10 years of experience, he synthesizes concept development through fabrication. He specializes in the development of comprehensive identity programs across wayfinding, signage programs, print, digital and other media.

|

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS