|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:6

|

Case study: Developing comprehensive community care in Japan - urban planning implications for long term dementia care

Yoshihiko Baba

Tohoku University School of Medicine, Japan

Tohoku University School of Medicine, Japan

Introduction

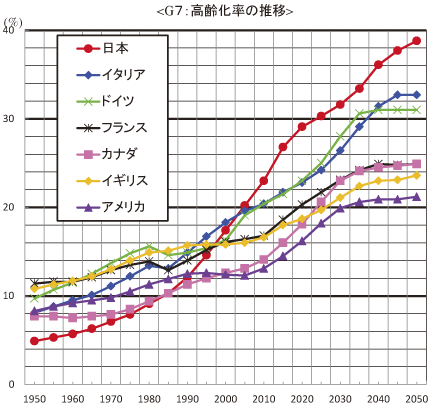

Aging in Japan is thought to outweigh all other nations, not only because the country has the highest proportion of elderly citizens but also because the rate of ageing has been rapid. The time taken for the proportion of the population who is elderly to grow from 7% to 14% was 115 years for France, 47 years for the UK, 40 years for Germany, but just 24 years for Japan.(7% in 1970, 14% in 1994 and 21% by 2007, Figure 1). One of the important considerations around ageing is the increasing prevalence of dementia. In 2012, the number of older adults with dementia in Japan was estimated to be 4.62 million people (15% of older adults), and this number is estimated to increase to 7.30 million (20.5%) by 2025.

To address this population trend, the government has had to reform Japan's long term care (LTC) policies and systems. In 1989, the government implemented the Gold Plan, a 10 Year Strategy of Health and Welfare for the Aged, but in 1994 the plan had to be rewritten as the ageing of the society progressed beyond their expectations. In 1997, the Long Term Care Insurance Act was legislated and public insurance for long term care started in 2000. Fifty percent of LCT insurance is now funded by the insurance, and the rest is funded by taxation.

Aging in Japan is thought to outweigh all other nations, not only because the country has the highest proportion of elderly citizens but also because the rate of ageing has been rapid. The time taken for the proportion of the population who is elderly to grow from 7% to 14% was 115 years for France, 47 years for the UK, 40 years for Germany, but just 24 years for Japan.(7% in 1970, 14% in 1994 and 21% by 2007, Figure 1). One of the important considerations around ageing is the increasing prevalence of dementia. In 2012, the number of older adults with dementia in Japan was estimated to be 4.62 million people (15% of older adults), and this number is estimated to increase to 7.30 million (20.5%) by 2025.

To address this population trend, the government has had to reform Japan's long term care (LTC) policies and systems. In 1989, the government implemented the Gold Plan, a 10 Year Strategy of Health and Welfare for the Aged, but in 1994 the plan had to be rewritten as the ageing of the society progressed beyond their expectations. In 1997, the Long Term Care Insurance Act was legislated and public insurance for long term care started in 2000. Fifty percent of LCT insurance is now funded by the insurance, and the rest is funded by taxation.

Figure 1: Demographic change - percentage of older people within the population of G7 countries (Japan is red)

Source: Soumu ICT Report on ICT Super Aged Society Vision, 総務省「ICT超高齢社会構想会議報告書」

Japan - Red, Blue - Italy, Green - Germany, Black - France, Pink - Canada, Yellow - UK, Purple - USA

Source: Soumu ICT Report on ICT Super Aged Society Vision, 総務省「ICT超高齢社会構想会議報告書」

Japan - Red, Blue - Italy, Green - Germany, Black - France, Pink - Canada, Yellow - UK, Purple - USA

In 2006, the concept of “comprehensive community care” was considered by a study group designated by the Director of Elderly Health in Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and described in their report, Elderly Care towards 2015. The report addressed several issues, such as preventative care and rehabilitation, and it defined a new care model for older adults with dementia. The proposed policies include introduction of Small-scale, Multifunctional At-home Care (SMAC), Daily Activities Areas and Comprehensive Community Support Centre. This was a major amendment in the long term care (LTC) insurance system of Japan and is often cited as “a shift from at-home care to community care”. This shift implies that LTC may be improved by better urban planning and design.

The report Elderly Care towards 2015 addressed the then issues of LTCI insurance and proposed four policy amendments:

The report Elderly Care towards 2015 addressed the then issues of LTCI insurance and proposed four policy amendments:

- Prevention and advanced rehabilitation

- New care services: (a) 24/7/365 care services; (b) new housing for older adults; (c) a better facility service; and (d) Comprehensive Community Care

- A new care model for people with dementia

- Better care quality

Definitions

The 2005 amendment to Long Term Care Insurance (LCTI) Act introduced several new services and new concepts:

Small-scale, Multifunctional At-home Care (SMAC) is one of LCTI services which aims to provide elderly care support, 24 hours a day, 365 days per year, for those who wish to continue to live at home or in the community. The report proposed that such services would be available at all Daily Activities Areas (DAA).

Daily Activities Areas (DAAs) are geographical boundaries in which older adults may easily conduct their activities of daily living, and is considered as wide as junior high school catchment areas. Each municipality sets Daily Activities Areas every three years as part of the municipality's Insured Long-Term Care Service Plans (the plans), considering local needs and conditions. The number of SMACs, as well as other Community-Based care services, to be established may be explicitly set in the plans.

Comprehensive Community Support Centres (CCSC) are public institutions established based on the population of adults of aged 65 years or older. According to the circular by MHLW (老計発第1018001号 老振発第1018001号 老老発第1018001号), one centre may support between 3,000 and 6,000 older adults. Each centre has a team of a public health nurse, a senior care manager and a social worker.

The 2005 amendment to Long Term Care Insurance (LCTI) Act introduced several new services and new concepts:

Small-scale, Multifunctional At-home Care (SMAC) is one of LCTI services which aims to provide elderly care support, 24 hours a day, 365 days per year, for those who wish to continue to live at home or in the community. The report proposed that such services would be available at all Daily Activities Areas (DAA).

Daily Activities Areas (DAAs) are geographical boundaries in which older adults may easily conduct their activities of daily living, and is considered as wide as junior high school catchment areas. Each municipality sets Daily Activities Areas every three years as part of the municipality's Insured Long-Term Care Service Plans (the plans), considering local needs and conditions. The number of SMACs, as well as other Community-Based care services, to be established may be explicitly set in the plans.

Comprehensive Community Support Centres (CCSC) are public institutions established based on the population of adults of aged 65 years or older. According to the circular by MHLW (老計発第1018001号 老振発第1018001号 老老発第1018001号), one centre may support between 3,000 and 6,000 older adults. Each centre has a team of a public health nurse, a senior care manager and a social worker.

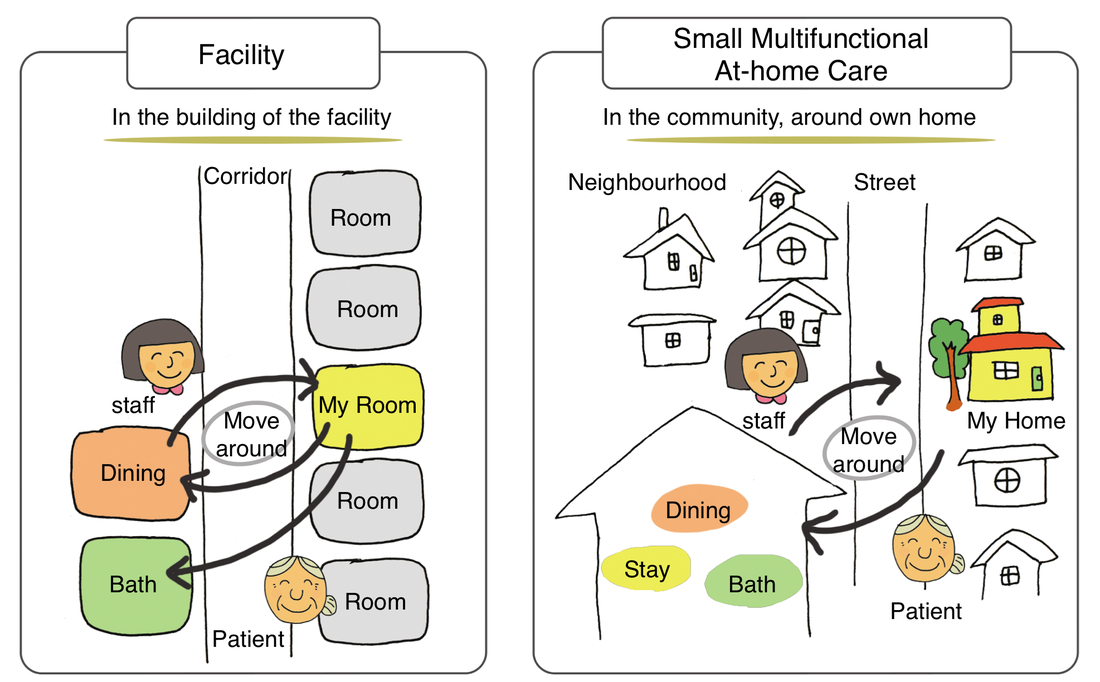

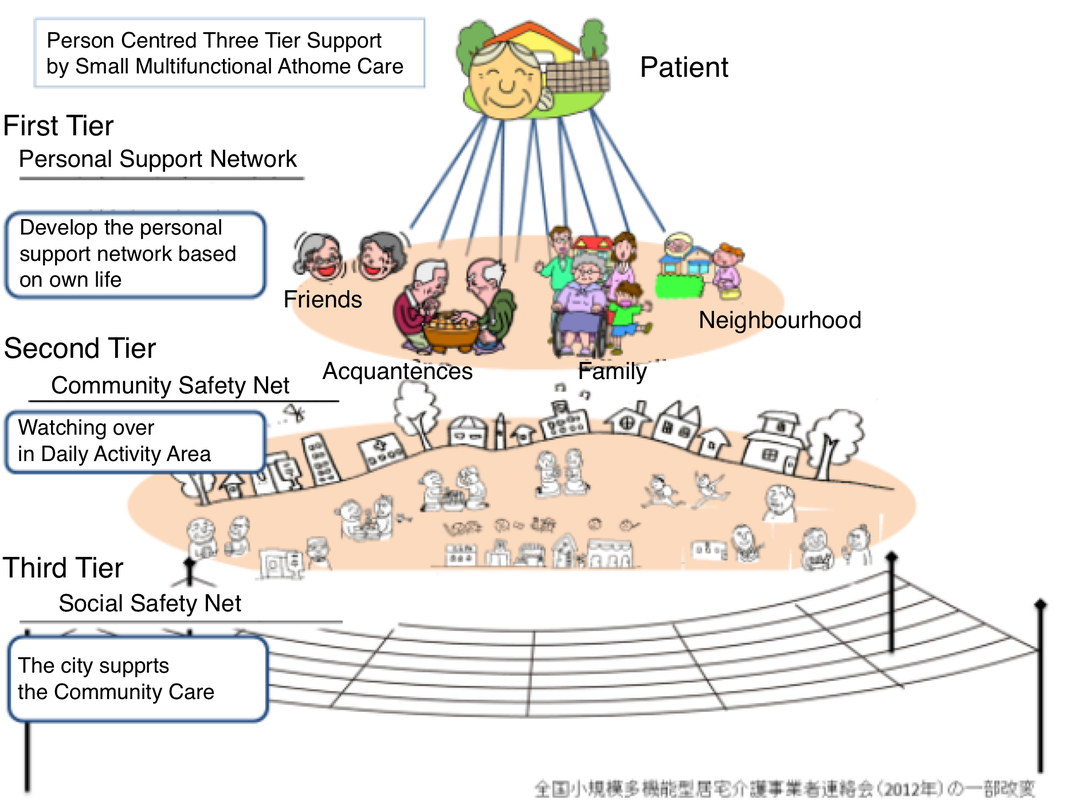

Tsuyoshi Koyama, one of the invited guests to the study group explained Comprehensive Community Care: “Take the community as hospital, their home is hospital bed and the streets are hospital corridor” (Figure 2). To implement his idea, it is essential to have 24/7/365 in-home care support.

Figure 2: From facility care to small multifunctional at-home care

Source: (translation by the author)

Source: (translation by the author)

Koyama did not only propose the concept of comprehensive community care, but also to generalise it. As a director of a nursing home with 100 beds in Nagaoka, he made a decision to split his nursing home into 5 smaller homes, each of which accommodates approximately 20 beds. He also established 17 in-home care centres in the city.

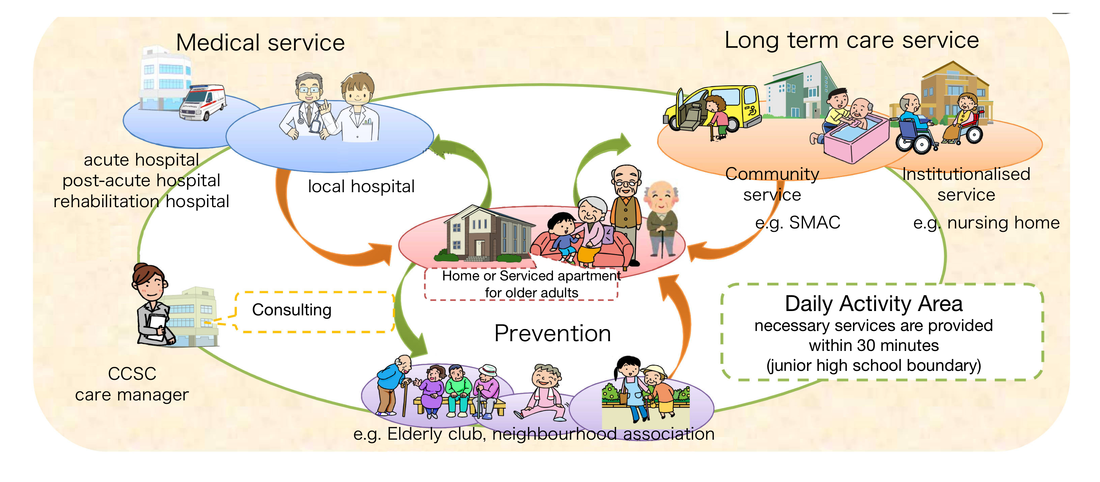

Comprehensive Community Care has been, and still is, discussed by many researchers and practitioners. It is now explained thus: towards 2025, when babyboomers become >=75 years old, we will establish a Comprehensive Community Care system in which they will be able to live their lives with pride, with appropriate housing, health care, long term care, prevention and life support services (Figure 3). In comprehensive community care, informal care, provided by people such as family, neighbours and volunteers, are as important as formal care. Care managers are trained to survey and make the best use of informal care, and community care meetings are held at DAA to discuss individual cases.

Comprehensive Community Care has been, and still is, discussed by many researchers and practitioners. It is now explained thus: towards 2025, when babyboomers become >=75 years old, we will establish a Comprehensive Community Care system in which they will be able to live their lives with pride, with appropriate housing, health care, long term care, prevention and life support services (Figure 3). In comprehensive community care, informal care, provided by people such as family, neighbours and volunteers, are as important as formal care. Care managers are trained to survey and make the best use of informal care, and community care meetings are held at DAA to discuss individual cases.

Evaluating Long Term Care Services Plans - and the role of urban design

Under the Long-Term Care Insurance Act, the local governments prepares a Long Term Care Services Plan every three years. The Fifth Insured Long-Term Care Service Plan period is 2012 to 2015, the period which to which Elderly Care towards 2015 was originally targeted. While MHLW shifted the target year of achieving comprehensive community care ten years forward to 2025, at this stage, it still is reasonable to evaluate to what extent comprehensive community care has been implemented and to examine the role of urban planning and design in improving LTC. The purpose of this case study is therefore to assess the Fifth Insured Long-Term Care Service Plans (2012-2015) and identify to what extent the policies relevant to dementia care in the community proposed by the report have been achieved.

Under the Long-Term Care Insurance Act, the local governments prepares a Long Term Care Services Plan every three years. The Fifth Insured Long-Term Care Service Plan period is 2012 to 2015, the period which to which Elderly Care towards 2015 was originally targeted. While MHLW shifted the target year of achieving comprehensive community care ten years forward to 2025, at this stage, it still is reasonable to evaluate to what extent comprehensive community care has been implemented and to examine the role of urban planning and design in improving LTC. The purpose of this case study is therefore to assess the Fifth Insured Long-Term Care Service Plans (2012-2015) and identify to what extent the policies relevant to dementia care in the community proposed by the report have been achieved.

Figure 4: Three-tier care for people with dementia

Progress of Comprehensive Community Care

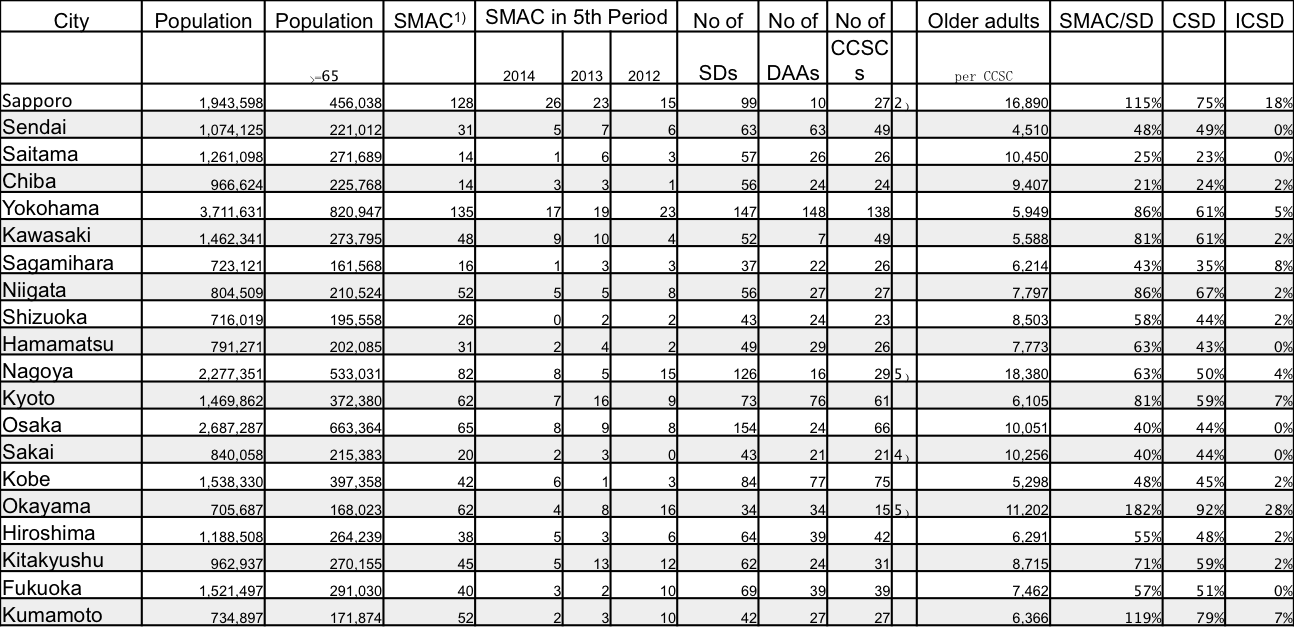

The Fifth Insured Long-Term Care Service Plans are examined to compare Daily Activities Areas and CCSCs. Then, the locations of SMACs and boundaries of DAAs and junior high schools are plotted on GIS. The target cities are 20 Designated Cities (seirei shitei toshi). The results are described in Table 1.

The Fifth Insured Long-Term Care Service Plans are examined to compare Daily Activities Areas and CCSCs. Then, the locations of SMACs and boundaries of DAAs and junior high schools are plotted on GIS. The target cities are 20 Designated Cities (seirei shitei toshi). The results are described in Table 1.

Table 1: Impelementation of Comprehensive Community Care in 20 Designated Cities

Table 1 definitions

School District (SD): The school districts of municipal junior high schools.

SMAC/SD: The number of SMACs per the number of SDs.

Covered School District (CSD): The number of SDs with SMACs per the number of all SDs.

Intensively Covered School District (ICSD): The number of SDs with two or more SMACs per the number of all SDs.

School District (SD): The school districts of municipal junior high schools.

SMAC/SD: The number of SMACs per the number of SDs.

Covered School District (CSD): The number of SDs with SMACs per the number of all SDs.

Intensively Covered School District (ICSD): The number of SDs with two or more SMACs per the number of all SDs.

Daily Activities Areas (DAAs)

Of the 20 Designated Cities, four cities adopted municipal wards as DAAs; five cities adopted junior high school boundaries; four cities merged several junior high school boundaries; two cities used local community areas called chonaikai; and five cities did not explicitly show how the municipality designated DAAs.

Comprehensive Community Support Centres (CCSC)

CCSCs have been established, but do not always meet the Government standard of covering 3,000 to 6,000 older adults; in fact, only Sendai, Yokohama, Kawasaki and Kobe meet the standard. Note that Sapporo, Nagoya, Okayama and Sakai have sub-centres.

Small-scale Multifunctional At-Home Care (SMAC)

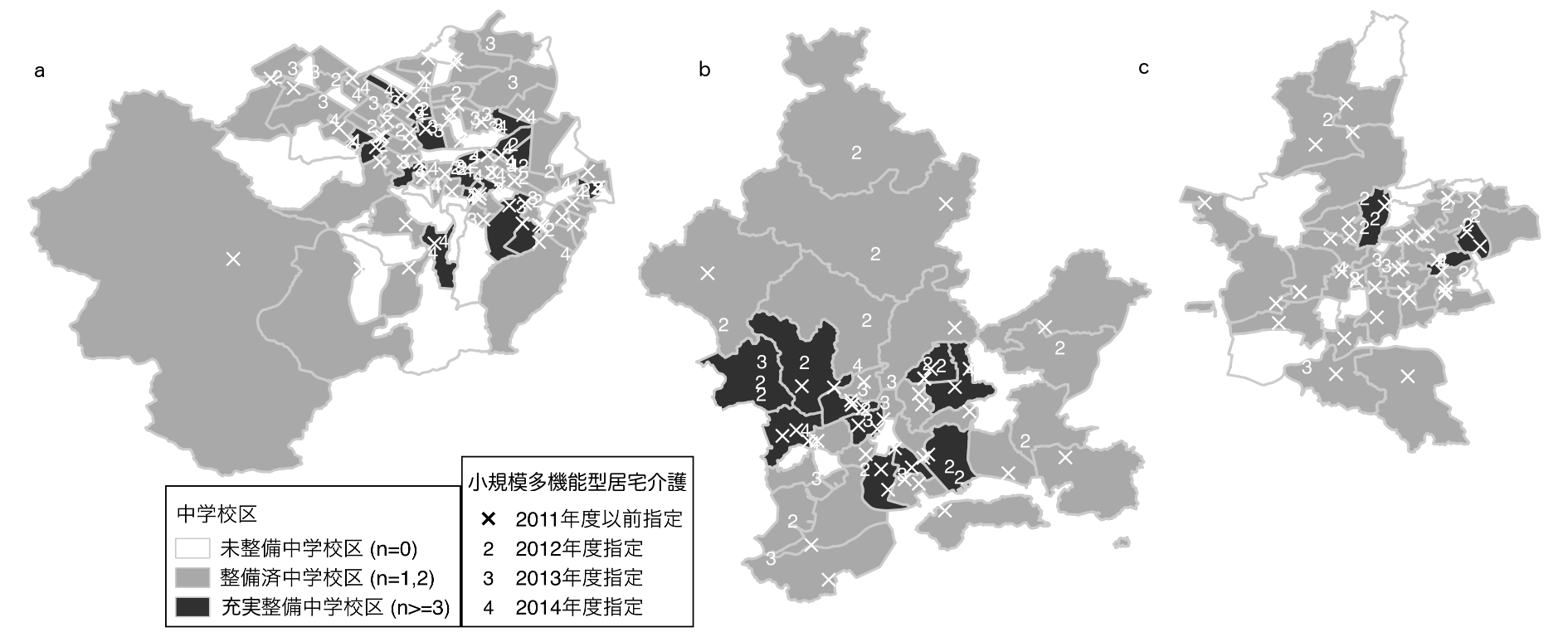

In some cities (Okayama, Kumamoto and Sapporo, Figure 5), there are more SMACs than junior high schools. However, in many cities, the SMAC/school district ratio is still under 50%. In some cities, the number of school districts that are covered by SMAC (CSD) is lower than SMAC/SD. This implies that SMACs cluster in certain school districts, usually in the suburbs where population of older adults is large and land value is relatively low.

Of the 20 Designated Cities, four cities adopted municipal wards as DAAs; five cities adopted junior high school boundaries; four cities merged several junior high school boundaries; two cities used local community areas called chonaikai; and five cities did not explicitly show how the municipality designated DAAs.

Comprehensive Community Support Centres (CCSC)

CCSCs have been established, but do not always meet the Government standard of covering 3,000 to 6,000 older adults; in fact, only Sendai, Yokohama, Kawasaki and Kobe meet the standard. Note that Sapporo, Nagoya, Okayama and Sakai have sub-centres.

Small-scale Multifunctional At-Home Care (SMAC)

In some cities (Okayama, Kumamoto and Sapporo, Figure 5), there are more SMACs than junior high schools. However, in many cities, the SMAC/school district ratio is still under 50%. In some cities, the number of school districts that are covered by SMAC (CSD) is lower than SMAC/SD. This implies that SMACs cluster in certain school districts, usually in the suburbs where population of older adults is large and land value is relatively low.

Figure 5: GIS analysis of SMACs in three cities: a. Sapporo b. Okayama c. Kumamoto

White: No SMAC in the school district; Grey: Covered School District (one or two SMACs); Black: Intensively Covered School District (three or more SMACs)

X: SMACs designated in or before 2011 (X), 2012 (2), 2013 (3) and 2014 (4)

X: SMACs designated in or before 2011 (X), 2012 (2), 2013 (3) and 2014 (4)

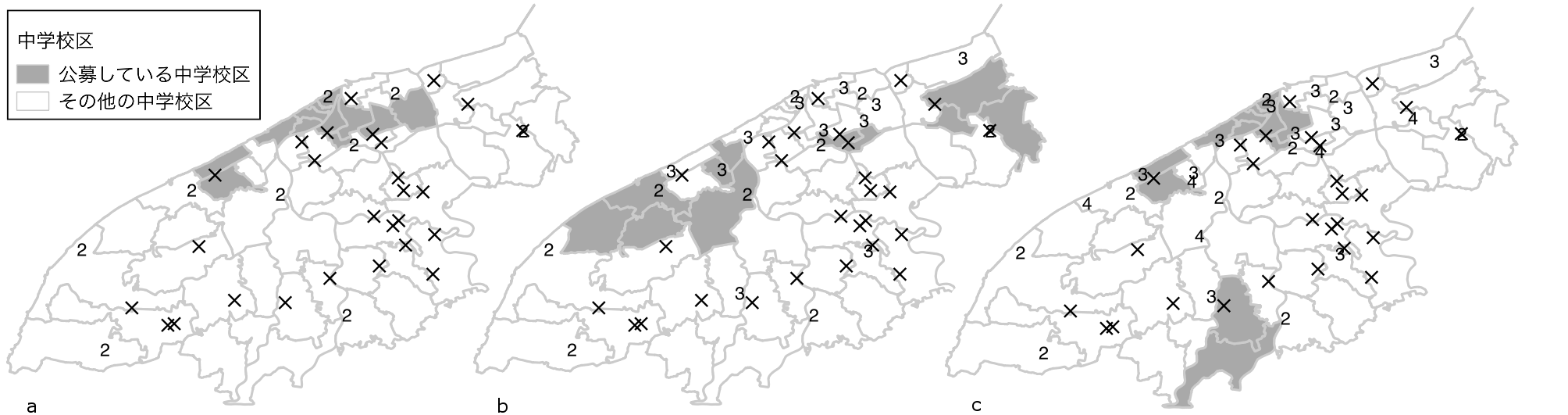

Several cities plan SMACs with geographical consideration. Niigata, for example, calls for SMACs in specified DAAs four times a year (Figure 6). In 2012, the city centre of Niigata had few SMAC, therefore called for several SMACs. The following year, nine SMACs were built in the area along with another SMAC in the rural area. In 2013, the suburban areas called for SMACs and five were built in the following year. With spatial planning, Niigata has successfully developed SMACs with geographical consideration.

Figure 6: Development of SMACs in Niigata

White: School District in which SMACs are NOT called for.

X: SMACs designated in or before 2011 (X), 2012 (2), 2013 (3) and 2014 (4)

X: SMACs designated in or before 2011 (X), 2012 (2), 2013 (3) and 2014 (4)

Discussion

Comprehensive community care may take older adults out of nursing homes to receive care in their own homes. Consequently, instead of living in an institution, these older adults with care needs will live in the community and will increase their physical activity. This is particularly important for patients with depression and dementia. When a person with depression of dementia spends more time outside, this can improve their symptoms. These patients tend to be sedentary (van Alphen et. al. 2016), and the increased physical activity they often experience in the community can help improve their mental and psychosocial health (Aoyagi 2010). Another important issue is wandering. Older adults with dementia sometimes wander in the community and, when found, involuntary medical restraint may be applied. However, part of comprehensive community care involves developing methods for early finding of such wanders. Currently, there is no single solution for early finding, but many cities have been attempting various methods via Comprehensive Community Support Centres.

The report Elderly Care towards 2015 set the goal of Comprehensive Community Care by 2015, but the government extended this to 2025, which seems the right decision, given that SMACs have been achieved in many cities, but more than half of the cities surveyed have not yet achieved the goal. Furthermore, the survey is limited to the large cities, and SMACs may be less developed in smaller cities.

The concept of Daily Activities Areas has been treated differently between the cities. In some cities, DAA is merely considered to cover the ward of the municipality. In other cities, it is a target area of SMAC developments. Unfortunately, most cities do not see DAA from the viewpoints of older adults, and have not yet started to fully utilise their potential. Osaka, for instance, has set DAAs as municipal wards and “development areas” as junior high school districts. However, Kawasaki, on the other hand, has taken a more interesting approach. Kawasaki describes the DAA as “an area around a railway station in which people spend their lives” and sets “community care areas” as junior high school districts, around CCSCs, which are more community-oriented than DAAs. Perhaps it is necessary to rethink the purpose and role of DAAs.

Implications

Comprehensive Community Care is an innovative concept of new community care model. It is not merely a reform in long term care, or a collection of 'good practices', but a reform of society in general. Japan has learned from a large number of case studies and from healthcare and long term care system experiences in other nations. Comprehensive Community Care incorporates urban planning to deliver care outside of nursing homes and researchers and practitioners are working together to further develop the concept.

Comprehensive community care may take older adults out of nursing homes to receive care in their own homes. Consequently, instead of living in an institution, these older adults with care needs will live in the community and will increase their physical activity. This is particularly important for patients with depression and dementia. When a person with depression of dementia spends more time outside, this can improve their symptoms. These patients tend to be sedentary (van Alphen et. al. 2016), and the increased physical activity they often experience in the community can help improve their mental and psychosocial health (Aoyagi 2010). Another important issue is wandering. Older adults with dementia sometimes wander in the community and, when found, involuntary medical restraint may be applied. However, part of comprehensive community care involves developing methods for early finding of such wanders. Currently, there is no single solution for early finding, but many cities have been attempting various methods via Comprehensive Community Support Centres.

The report Elderly Care towards 2015 set the goal of Comprehensive Community Care by 2015, but the government extended this to 2025, which seems the right decision, given that SMACs have been achieved in many cities, but more than half of the cities surveyed have not yet achieved the goal. Furthermore, the survey is limited to the large cities, and SMACs may be less developed in smaller cities.

The concept of Daily Activities Areas has been treated differently between the cities. In some cities, DAA is merely considered to cover the ward of the municipality. In other cities, it is a target area of SMAC developments. Unfortunately, most cities do not see DAA from the viewpoints of older adults, and have not yet started to fully utilise their potential. Osaka, for instance, has set DAAs as municipal wards and “development areas” as junior high school districts. However, Kawasaki, on the other hand, has taken a more interesting approach. Kawasaki describes the DAA as “an area around a railway station in which people spend their lives” and sets “community care areas” as junior high school districts, around CCSCs, which are more community-oriented than DAAs. Perhaps it is necessary to rethink the purpose and role of DAAs.

Implications

Comprehensive Community Care is an innovative concept of new community care model. It is not merely a reform in long term care, or a collection of 'good practices', but a reform of society in general. Japan has learned from a large number of case studies and from healthcare and long term care system experiences in other nations. Comprehensive Community Care incorporates urban planning to deliver care outside of nursing homes and researchers and practitioners are working together to further develop the concept.

References

Aoyagi, Yukitoshi and Park, Hyuntae and Watanabe, Eiji and Park, Sungjin and Shephard, Roy J (2010) Habitual physical activity and physical fitness in older Japanese adults: the Nakanojo Study, Gerontology, 55 (5), 523-531

総務省「ICT超高齢社会構想会議報告書」

Ogino H (2016) Social Welfare developed by Tsuyoshi Koyama, Chuohoki. (萩野浩基 (2016) 『小山剛の拓いた社会福祉』中央法規出版)

全国小規模多機能型居宅介護事業者連絡会 (2017) 小規模多機能型居宅介護の機能強化に向けた今後のあり方に関する調査研究事業報告書

van Alphen HJM, Volkers KM, Blankevoort CG, Scherder EJA, Hortobagyi T and van Heuvelen MJG (2016) Older Adults with Dementia Are Sedentary for Most of the Day, PLoS ONE

Aoyagi, Yukitoshi and Park, Hyuntae and Watanabe, Eiji and Park, Sungjin and Shephard, Roy J (2010) Habitual physical activity and physical fitness in older Japanese adults: the Nakanojo Study, Gerontology, 55 (5), 523-531

総務省「ICT超高齢社会構想会議報告書」

Ogino H (2016) Social Welfare developed by Tsuyoshi Koyama, Chuohoki. (萩野浩基 (2016) 『小山剛の拓いた社会福祉』中央法規出版)

全国小規模多機能型居宅介護事業者連絡会 (2017) 小規模多機能型居宅介護の機能強化に向けた今後のあり方に関する調査研究事業報告書

van Alphen HJM, Volkers KM, Blankevoort CG, Scherder EJA, Hortobagyi T and van Heuvelen MJG (2016) Older Adults with Dementia Are Sedentary for Most of the Day, PLoS ONE

About the Author

|

Yoshihiko Baba is a PhD Candidate at the Department of Internal Medicine and Rehabilitation Science, Tohoku University School of Medicine. He gained his BSc from Kyoto University in Japan and MPhil Town Planning from Bartlett School of Planning, UCL in the UK. He works for an architectural firm in Tokyo which designs and manages Serviced Apartments for Older Adults and Long Term Care Insurance services. He is also a leading researcher of the Association of Small Multifunctional At-home Care, Tokyo. His research interest is in community rehabilitation to increase physical activity of older adults and its effects with emphasis on participation.

|

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS