|

Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 2017;3:12

|

ANALYSIS

Housing design for socialisation and wellbeing

Larissa Lai (1) and Paty Rios (2)

(1) Pratt Institute and Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, USA

(2) Happy City, Canada

(1) Pratt Institute and Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, USA

(2) Happy City, Canada

Key messages for urban planning and design

- Housing design affects mental health in many direct and indirect ways; sociability is an important factor.

- Multi-family housing can be designed to strengthen pro-social interactions towards better mental health.

- Happy Homes: A toolkit for building sociability through multi-family housing design condenses research, industry best practices, and innovative design actions to be used by designers, developers, researchers, and architects.

- 10 key principles: doing things together; exposure; tenure; social group size; feeling of safety; participation; walkability; nature; comfort; and culture and values.

Housing quality: a determinant of public mental health

In public health, it is imperative to address the social determinants of health and mental health: the system of factors in the physical and social environment that interact with the population’s health. One of these factors is housing condition and quality. There is significant evidence that sub-par housing conditions such as poor indoor air quality, high lead levels in paint, damp houses, high noise levels, presence of pests, and overcrowding can contribute to health problems such as asthma, infectious and chronic diseases, and mental health issues such as stress, anxiety, and depression (Krieger & Higgins, 2002; Srinivasan, O’Fallon, & Dearry, 2003). Some of the housing condition elements directly associated with poor mental health have been addressed by various local governments through regulation of sanitation standards building codes to ensure housing quality for residents.

Direct and indirect housing factors affecting health and mental health

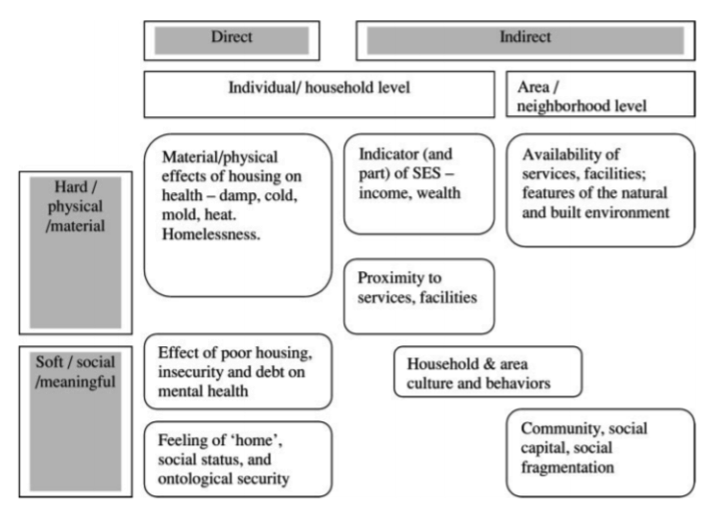

While most of the elements associated with poor material housing conditions can have a direct impact on an individual’s physical and mental health, some scholars have delved further into the research examining indirect health effects which relate to psychosocial processes such as personal control, socially supportive relationships, and restoration from stress and fatigue (Evans, 2003). The vast number of mediating processes and confounding factors involved can make it challenging to understand the extent to which various elements exert these indirect impacts (Figure 1). In contrast to direct factors (such as regulating the use of lead-based paint indoors) it can be harder to pinpoint the exact mechanisms and relationships of indirect factors, and more difficult to produce reliable research and interventions in tackling these problems. One factor that warrants further consideration is socialisation and wellbeing.

In public health, it is imperative to address the social determinants of health and mental health: the system of factors in the physical and social environment that interact with the population’s health. One of these factors is housing condition and quality. There is significant evidence that sub-par housing conditions such as poor indoor air quality, high lead levels in paint, damp houses, high noise levels, presence of pests, and overcrowding can contribute to health problems such as asthma, infectious and chronic diseases, and mental health issues such as stress, anxiety, and depression (Krieger & Higgins, 2002; Srinivasan, O’Fallon, & Dearry, 2003). Some of the housing condition elements directly associated with poor mental health have been addressed by various local governments through regulation of sanitation standards building codes to ensure housing quality for residents.

Direct and indirect housing factors affecting health and mental health

While most of the elements associated with poor material housing conditions can have a direct impact on an individual’s physical and mental health, some scholars have delved further into the research examining indirect health effects which relate to psychosocial processes such as personal control, socially supportive relationships, and restoration from stress and fatigue (Evans, 2003). The vast number of mediating processes and confounding factors involved can make it challenging to understand the extent to which various elements exert these indirect impacts (Figure 1). In contrast to direct factors (such as regulating the use of lead-based paint indoors) it can be harder to pinpoint the exact mechanisms and relationships of indirect factors, and more difficult to produce reliable research and interventions in tackling these problems. One factor that warrants further consideration is socialisation and wellbeing.

Figure 1: Direct/indirect and soft/hard housing elements affecting health and mental health (adapted from Shaw, 2004)

Interacting housing elements and mental health: the case of high rise living

Multiple studies have indicated that high rise living correlates with poorer mental health. This is not just because high rise residents often have lower income and access to fewer resources, but due to correlations between measures of social support and connectedness and people's wellbeing, quality of life and mental health outcomes (Eom, et al., 2013). Living on higher floors or in high-rise buildings may create difficulties for children and their parents in accessing open spaces for play; similarly living in high-rise complexes with many other families heightens safety concerns, and studies have shown correlations with fewer instances of friendly interaction with neighbors compared to interactions between residents of smaller low-rise houses (Evans, Wells, & Moch, 2003). Social isolation is of particular interest in senior care. Many older people become socially isolated, negatively affecting their physical and mental health (Cattan, et al., 2005). Various social service interventions and programs such as support groups, social day care programs, home visiting programs, and even the Campaign to End Loneliness (UK) have been set up to promote social support and connectedness for older people, yet the efficacy of such interventions are not conclusive (Findlay, 2003).

The role of housing in exacerbating and alleviating social isolation

We know that the built environment can impact people's social connections; certain aspects and design elements of the built environment such as the use of open spaces, seating, and housing clusters are well known to be more conducive to promoting socialization between neighbors (Brown, et al., 2009). Some community members have taken initiative and worked with developers and architects to design and build their own sustainable, socially-focused co-housing communities. However, the collaboration needed to implement housing design that promotes social support and connectedness can be perceived as challenging, and of course public health agencies do not normally design or maintain housing (Krieger & Higgins, 2002).

"While architects focus on novel forms, and public space advocates talk about the potential for park or plaza design to boost social connections, the evidence suggests that we continue to design and build housing that corrodes social wellbeing. Millions of people are moving to high-density housing around the world. Developers and policy-makers need be guided by evidence or we risk building a new generation of unhealthy, isolating homes."

- Charles Montgomery, Founder and Principal, Happy City

A new tool for social wellbeing and sociability in multi-family housing design

And yet there is a wide range of factors that can promote social wellbeing and sociability in housing design. This design and planning opportunity is the focus of a new toolkit, Happy City's Happy Homes: A toolkit for building sociability through multi-family housing design. This toolkit condenses research and industry best practices into strategies and actions to guide housing design for social wellbeing. Suitable for use by designers, developers, researchers, architects and anyone who is interested in promoting sociability in their building, the toolkit is available for free to the public online in an interactive web format and additionally in PDF format suitable for printing as postcard decks to facilitate working with clients in person.

The toolkit was developed by Happy City, an organization founded by Charles Montgomery, author of the book Happy City, Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design, which critically examines how urban design interfaces with attaining happiness and wellbeing. The team at Happy City, who consult for wellbeing and happiness through the design of the environment at different scales, initiated the project about one and a half years ago in response to the two critical housing challenges impacting the Vancouver community at that time: affordability and sociability. Like many metropolitan areas worldwide, Vancouver has been experiencing a housing affordability crisis, a matter many developers and the municipality have been attempting to tackle. The Vancouver Foundation’s 2012 Connections and Engagement survey reported social isolation as a primary concern for City of Vancouver residents. With the Happy City team’s experience in both practice and research of human wellbeing in urban environments, the team launched the Happy Homes Project to address housing affordability and sociability together to bring about sustainable quality living for the city’s residents. The team took inspiration from North Vancouver’s Active Design Guidelines published in 2015 which is a brief document illustrating ideas encouraging daily physical fitness and social interaction in buildings. While the City’s guidelines focused largely on physical health opportunities, Happy City's Happy Homes toolkit focused on the sociability factor.

The Happy Homes project involved an expansive multidisciplinary literature review, and interviews conducted with a range of stakeholders from architects to sociologists and neuroscientists. Following analysis of the material, the entire Happy City team gathered in a workshop session to condense the work into ten key principles that underly the toolkit:

Multiple studies have indicated that high rise living correlates with poorer mental health. This is not just because high rise residents often have lower income and access to fewer resources, but due to correlations between measures of social support and connectedness and people's wellbeing, quality of life and mental health outcomes (Eom, et al., 2013). Living on higher floors or in high-rise buildings may create difficulties for children and their parents in accessing open spaces for play; similarly living in high-rise complexes with many other families heightens safety concerns, and studies have shown correlations with fewer instances of friendly interaction with neighbors compared to interactions between residents of smaller low-rise houses (Evans, Wells, & Moch, 2003). Social isolation is of particular interest in senior care. Many older people become socially isolated, negatively affecting their physical and mental health (Cattan, et al., 2005). Various social service interventions and programs such as support groups, social day care programs, home visiting programs, and even the Campaign to End Loneliness (UK) have been set up to promote social support and connectedness for older people, yet the efficacy of such interventions are not conclusive (Findlay, 2003).

The role of housing in exacerbating and alleviating social isolation

We know that the built environment can impact people's social connections; certain aspects and design elements of the built environment such as the use of open spaces, seating, and housing clusters are well known to be more conducive to promoting socialization between neighbors (Brown, et al., 2009). Some community members have taken initiative and worked with developers and architects to design and build their own sustainable, socially-focused co-housing communities. However, the collaboration needed to implement housing design that promotes social support and connectedness can be perceived as challenging, and of course public health agencies do not normally design or maintain housing (Krieger & Higgins, 2002).

"While architects focus on novel forms, and public space advocates talk about the potential for park or plaza design to boost social connections, the evidence suggests that we continue to design and build housing that corrodes social wellbeing. Millions of people are moving to high-density housing around the world. Developers and policy-makers need be guided by evidence or we risk building a new generation of unhealthy, isolating homes."

- Charles Montgomery, Founder and Principal, Happy City

A new tool for social wellbeing and sociability in multi-family housing design

And yet there is a wide range of factors that can promote social wellbeing and sociability in housing design. This design and planning opportunity is the focus of a new toolkit, Happy City's Happy Homes: A toolkit for building sociability through multi-family housing design. This toolkit condenses research and industry best practices into strategies and actions to guide housing design for social wellbeing. Suitable for use by designers, developers, researchers, architects and anyone who is interested in promoting sociability in their building, the toolkit is available for free to the public online in an interactive web format and additionally in PDF format suitable for printing as postcard decks to facilitate working with clients in person.

The toolkit was developed by Happy City, an organization founded by Charles Montgomery, author of the book Happy City, Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design, which critically examines how urban design interfaces with attaining happiness and wellbeing. The team at Happy City, who consult for wellbeing and happiness through the design of the environment at different scales, initiated the project about one and a half years ago in response to the two critical housing challenges impacting the Vancouver community at that time: affordability and sociability. Like many metropolitan areas worldwide, Vancouver has been experiencing a housing affordability crisis, a matter many developers and the municipality have been attempting to tackle. The Vancouver Foundation’s 2012 Connections and Engagement survey reported social isolation as a primary concern for City of Vancouver residents. With the Happy City team’s experience in both practice and research of human wellbeing in urban environments, the team launched the Happy Homes Project to address housing affordability and sociability together to bring about sustainable quality living for the city’s residents. The team took inspiration from North Vancouver’s Active Design Guidelines published in 2015 which is a brief document illustrating ideas encouraging daily physical fitness and social interaction in buildings. While the City’s guidelines focused largely on physical health opportunities, Happy City's Happy Homes toolkit focused on the sociability factor.

The Happy Homes project involved an expansive multidisciplinary literature review, and interviews conducted with a range of stakeholders from architects to sociologists and neuroscientists. Following analysis of the material, the entire Happy City team gathered in a workshop session to condense the work into ten key principles that underly the toolkit:

10 key principles for social wellbeing and sociability in multi-family housing (from Happy City's Happy Homes toolkit)

- Doing things together: Provide spaces that increase opportunities for residents to interact and do enjoyable things together.

- Exposure: Define private, semi-private, and public spaces to enhance residents’ sense of privacy and control over their exposure to others.

- Tenure: Enhance design and policy measures that will allow residents to remain in their community, as social connections and trust are reinforced over time.

- Social group size: Social group size affects the quality of social interactions and relationships - use of private, semi-private, and public spaces, as well as the clustering of homes into groups.

- Feeling of safety: Environments that feel safe encourage people to build positive relationships with each other.

- Participation: Residents participating in the design and management of their living environment allow for social interaction and increased sense of belonging.

- Walkability: Neighborhoods with mixed-used spaces that encourage walking increase social interaction.

- Nature: Exposure to green spaces and residents participating in the care of green spaces promotes social wellbeing.

- Comfort: Pleasant and comfortable environments encourage people to socialize with each other.

- Culture and values: Places that reflect people’s identity, culture, and values enhances their attachment to places and increases their sense of belonging.

Using the toolkit

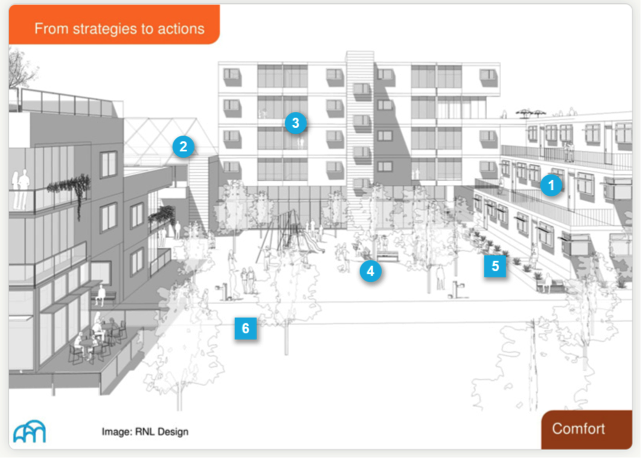

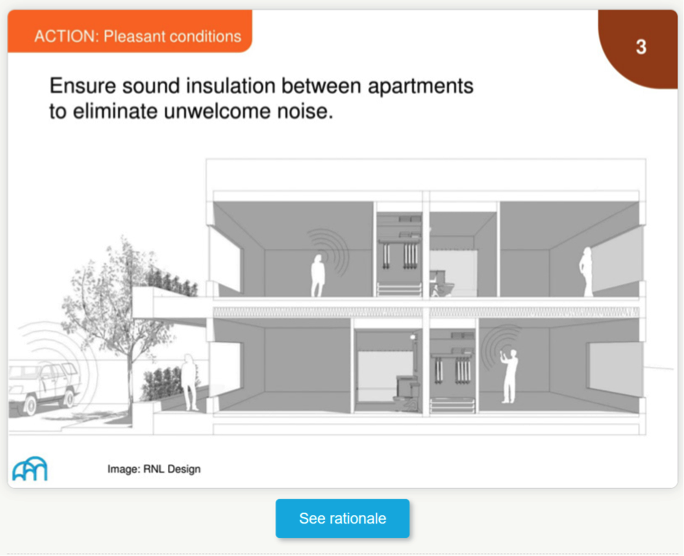

Happy City, along with RNL Design, created different multi-family housing development renderings to illustrate each of the 10 principles. With numbered circles, triangles and squares they identified specific design actions that can be materialized accordingly. When clicking on these icons, the user explores an “action” card (Figure 2 and 3) that can be flipped and find the “rationale” (Figure 4). Readers are guided through research-supported strategies to recommended action grounded on three domains: design & spatial (circle icons), programming (square icons), and policy.

Happy City, along with RNL Design, created different multi-family housing development renderings to illustrate each of the 10 principles. With numbered circles, triangles and squares they identified specific design actions that can be materialized accordingly. When clicking on these icons, the user explores an “action” card (Figure 2 and 3) that can be flipped and find the “rationale” (Figure 4). Readers are guided through research-supported strategies to recommended action grounded on three domains: design & spatial (circle icons), programming (square icons), and policy.

Figure 2: A multi-family housing graphic rendering with blue shapes marking places for potential comfort-related strategies

Figure 3: Action card taken from the key principle of comfort

Figure 4: Flip side of Figure 3 "Action" card is the “Rationale” card

How the toolkit is being used

At present, the Happy Homes team has been engaging with mostly developers and practitioners of the built environment. The City of Vancouver has been enthusiastic about the project’s potential in helping deliver long term positive change for the city’s housing arena. Moving forward, the team strives to involve different levels of government, as well as working more with experts in the realm of public health, and hopes to engage more with the general public.

This tool also offers the opportunity for public engagement. For the public, the issue of housing affordability is often seen as more of a priority than the issue of social connectedness. . However, a key insight from the toolkit is that we can actually boost affordability by designing housing that strengthens social connections. Facilitating a dialogue with the public can be helpful for identifying the ideas that resonate and are valued by the community residents and housing developers alike.

The Happy Homes toolkit is intended as an elementary set of ideas to invigorate the industry’s interest in considering housing design for affordability and sociability alongside each other, engaging more parties into the conversation to fast track fundamental concepts into more specific guidelines. The team believes in the importance for researchers, developers, practitioners, and policymakers to work collaboratively to change the way we think about, design, and build multi-family housing.

References

Brown, S. C., Mason, C. A., Lombard, J. L., Martinez, F., Plater-Zyberk, E., Spokane, A. R., ... & Szapocznik, J. (2009). The relationship of built environment to perceived social support and psychological distress in Hispanic elders: The role of “eyes on the street”. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 64(2), 234-246.

Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J., & Learmouth, A. (2005). Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing & Society, 25(1), 41-67.

Eom, C. S., Shin, D. W., Kim, S. Y., Yang, H. K., Jo, H. S., Kweon, S. S., ... & Park, J. H. (2013). Impact of perceived social support on the mental health and health‐related quality of life in cancer patients: results from a nationwide, multicenter survey in South Korea. Psycho‐Oncology, 22(6), 1283-1290.

Evans, G. W. (2003). The built environment and mental health. Journal of urban health, 80(4), 536-555.

Evans, G. W., Wells, N. M., & Moch, A. (2003). Housing and mental health: a review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. Journal of social issues, 59(3), 475-500.

Findlay, R. A. (2003). Interventions to reduce social isolation amongst older people: where is the evidence?. Ageing & Society, 23(5), 647-658.

Krieger, J., & Higgins, D. L. (2002). Housing and health: time again for public health action. American journal of public health, 92(5), 758-768.

Shaw, M. (2004). Housing and public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health, 25, 397-418.

Srinivasan, S., O’Fallon, L. R., & Dearry, A. (2003). Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. American journal of public health, 93(9), 1446-1450.

At present, the Happy Homes team has been engaging with mostly developers and practitioners of the built environment. The City of Vancouver has been enthusiastic about the project’s potential in helping deliver long term positive change for the city’s housing arena. Moving forward, the team strives to involve different levels of government, as well as working more with experts in the realm of public health, and hopes to engage more with the general public.

This tool also offers the opportunity for public engagement. For the public, the issue of housing affordability is often seen as more of a priority than the issue of social connectedness. . However, a key insight from the toolkit is that we can actually boost affordability by designing housing that strengthens social connections. Facilitating a dialogue with the public can be helpful for identifying the ideas that resonate and are valued by the community residents and housing developers alike.

The Happy Homes toolkit is intended as an elementary set of ideas to invigorate the industry’s interest in considering housing design for affordability and sociability alongside each other, engaging more parties into the conversation to fast track fundamental concepts into more specific guidelines. The team believes in the importance for researchers, developers, practitioners, and policymakers to work collaboratively to change the way we think about, design, and build multi-family housing.

References

Brown, S. C., Mason, C. A., Lombard, J. L., Martinez, F., Plater-Zyberk, E., Spokane, A. R., ... & Szapocznik, J. (2009). The relationship of built environment to perceived social support and psychological distress in Hispanic elders: The role of “eyes on the street”. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 64(2), 234-246.

Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J., & Learmouth, A. (2005). Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing & Society, 25(1), 41-67.

Eom, C. S., Shin, D. W., Kim, S. Y., Yang, H. K., Jo, H. S., Kweon, S. S., ... & Park, J. H. (2013). Impact of perceived social support on the mental health and health‐related quality of life in cancer patients: results from a nationwide, multicenter survey in South Korea. Psycho‐Oncology, 22(6), 1283-1290.

Evans, G. W. (2003). The built environment and mental health. Journal of urban health, 80(4), 536-555.

Evans, G. W., Wells, N. M., & Moch, A. (2003). Housing and mental health: a review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. Journal of social issues, 59(3), 475-500.

Findlay, R. A. (2003). Interventions to reduce social isolation amongst older people: where is the evidence?. Ageing & Society, 23(5), 647-658.

Krieger, J., & Higgins, D. L. (2002). Housing and health: time again for public health action. American journal of public health, 92(5), 758-768.

Shaw, M. (2004). Housing and public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health, 25, 397-418.

Srinivasan, S., O’Fallon, L. R., & Dearry, A. (2003). Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. American journal of public health, 93(9), 1446-1450.

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS

About the Author

|

Larissa Lai is a licensed social worker and researcher based in New York and a UD/MH Associate. She holds a Masters degree in Social Work from New York University and is about to undertake a Masters degree in City and Regional Planning at Pratt Institute. Larissa currently works as a psychotherapist and also in program design and evaluation for multiple social services and mental health agencies in the city. Her academic and research interests include critical theory, diversity issues, best practices and programming models for mental health, community impact, and innovative housing solutions.

|

|

Paty Rios is a project lead in Happy City, and focuses on promoting sociability and social well-being in the built environment. She has an interdisciplinary background in architecture, urban design, ethnography and participatory design. She collaborated with world-renowned architecture studio Teodoro González de Leon, Gensler & Peschard, co-founded In.Situ and the non-profit organization Identidad y Ciudad in Mexico. Paty promotes a human-centered design approach that engages a great spectrum of stakeholders to analyze and work with the nuances of social complexities. During her PhD she developed a participatory and interdisciplinary methodology to design urban parks that promote social cohesion. Her international experience has helped her understand the different perspectives as well as cultural values that link urban design with human patterns. She is a sessional lecturer UBC and has experience teaching urban theory, project and urban methodologies. Paty is also a postdoctoral fellow at Liu Institute and explores the relation between the policy design process and participatory design in the planning of the city.

Twitter: @riospaty |

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS